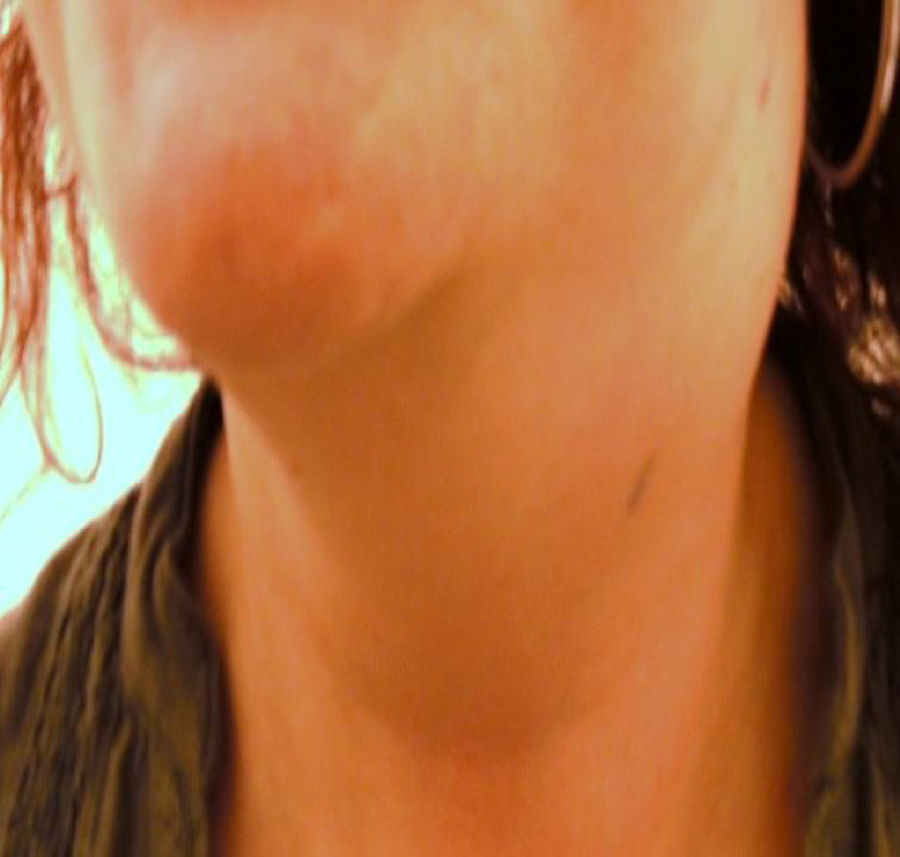

A previously healthy 39-year-old woman visited the emergency department due to a tumor in her left cervical region which had appeared in the past 15 days and was gradually increasing in size, accompanied by pruritus and night sweats. She had no pain or dysthermia. She had received an anti-inflammatory drug and spiramycin plus metronidazole for a week with no improvement. Her prior history of note included migraine headaches and allergic rhinitis. She reported no contact with animals or consumption of raw dairy products. A physical examination revealed a fixed mass with no pain or inflammation occupying the superior 1/3 of the left half of the neck (Fig. 1). There was no lymphadenopathy on the right side of the neck or in the rest of the examination. Nasofibroscopy revealed normal mucosa. It was decided to hospitalise the patient for study.

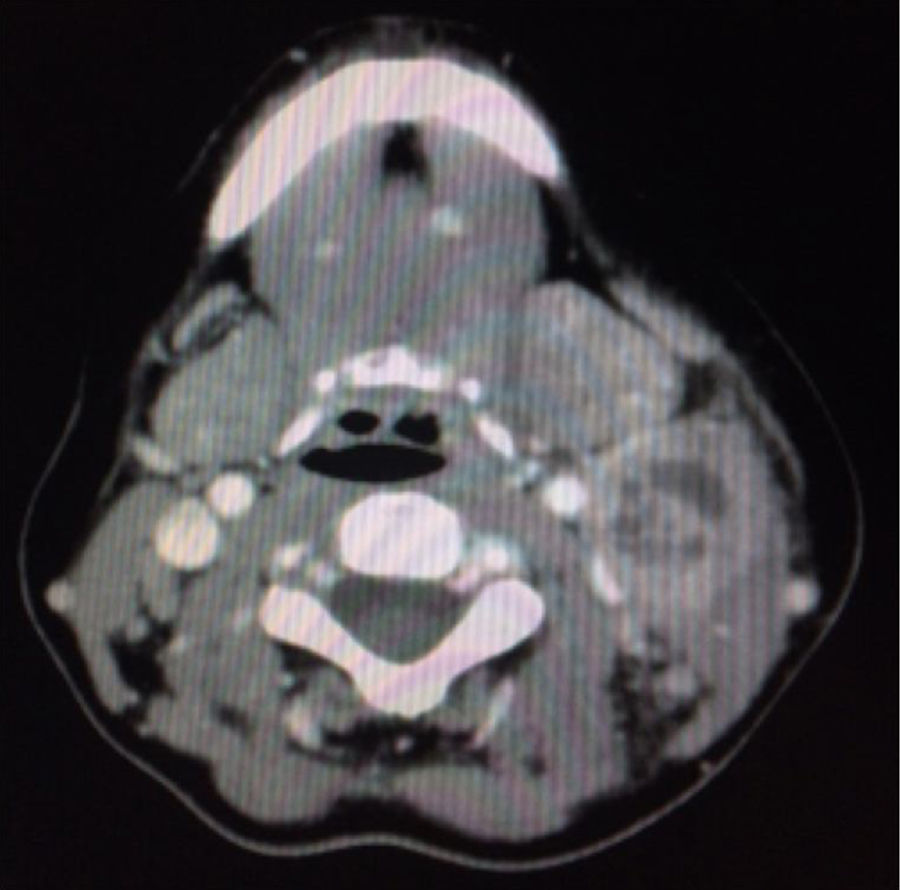

Laboratory testing revealed leukocytosis 12.2×109l−1, neutrophilia 9.64×109l, ESR 49mm/h and CRP 3.39mg/dl. Serology tests for HIV, HBV, HCV, EBV, CMV and syphilis were negative. A neck and chest CT scan showed a multinodular mass on the left side of the neck at levels IIA-IIB and III with central necrosis measuring 4cm×2.8cm (Fig. 2). A chest X-ray was normal. The patient was suspected of having disease of infectious etiology or lymphoproliferative disease. An FNAB was performed but was inconclusive due to a limited sample.

The patient was empirically treated with cefazolin 1g/8h plus methylprednisolone 40mg/12h. Following nine days of treatment with limited improvement, a biopsy was performed for study. A histopathology examination ruled out necrosis but not malignancy. A microbiological culture isolated a coccobacillus positive for Gram staining, catalase and urease and negative for pyrazinamidase and alkaline phosphatase.

Clinical courseThe bacterium was identified as Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis (C. pseudotuberculosis) (Fig. 3) using API-Coryne (bioMérieux®) and confirmed using mass spectrometry (Bruker Biotyper MALDI-TOF), with a score of 2.339 at a referral hospital. An antibiogram was prepared according to EUCAST criteria. Susceptibility to penicillin, clindamycin, rifampicin, tetracycline, vancomycin, ciprofloxacin and linezolid and resistance to gentamicin were obtained.

The patient was treated with oral erythromycin. She had slow progression which required readmission after a week for parenteral treatment with clindamycin (600mg/8h) plus amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (1g/8h) for seven days. After she improved, she was discharged with oral erythromycin (500mg/8h) for two more weeks. Her signs and symptoms completely resolved.

Final commentsThe main causes of lymphadenitis are infectious and tumoral. Infectious causes may be acute (bacterial or viral) or chronic (mycobacteria or chlamydiae).

In isolating C. pseudotuberculosis, it is important to confirm species identification in order to distinguish it from corynebacteria which cause similar signs and symptoms (Corynebacterium imitans) and other diphtheria toxin-producing species such as Corynebacterium diphtheriae (C. diphtheriae) and Corynebacterium ulcerans.1 A positive urease test presumptively distinguishes it from C. diphtheriae.2 Unconventional techniques such as rpoB gene sequencing, 16S rRNA sequencing and MALDI-TOF1,3 are needed for proper identification.

Lymphadenitis caused by C. pseudotuberculosis is an uncommon disease in humans. It mainly affects previously healthy male rural workers in contact with sheep and goat livestock.4–6 Transmission mainly occurs through skin lesions by means of direct contact (animals or animal products) or contact with contaminated environments.6 This infection has also been associated with consumption of raw dairy products from contaminated livestock, as well as inhalation of droplets containing the bacterium.5–7 The cervical location of the lymphadenopathy suggested oral transmission of the microorganism through raw milk from contaminated livestock.8 Although the patient did not report having ingested raw dairy products, we believe this to be the most likely route of acquisition as unpasteurised goat cheese is often consumed in our setting.

The most common manifestations of the disease are suppurative lymphadenopathy in different locations (axillary, inguinal and cervical), fever and/or myalgia with a chronic or subacute course.9,10

The patient was treated with macrolides, as recommended by the therapeutic guidelines. Surgical lymph node drainage is sometimes needed to ensure a favourable clinical course.7,8 In our case, it was not needed.

We wish to emphasise the importance of identifying this uncommon etiological agent in similar clinical cases for proper treatment and resolution of signs and symptoms.

Please cite this article as: García de Hombre AM, Bonadeo A, Suárez-Bordón P, Sánchez-Oñoro M. Tumor cervical de etiología inusual. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:525–526.