The recommendation for pertussis vaccination in pregnancy was established in Catalonia in February 2014. The objective of this study was to compare the hospitalisation rate for pertussis in children under one year of age before and after the implementation of the vaccination programme.

MethodsObservational and retrospective study of patients under one year of age admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of pertussis. The hospitalisation rate of patients under one year of age of the period prior to the vaccination programme (2008−2013) was compared with the period with vaccination programme (2014−2019) in the total of children under one year of age and in 2 subgroups: children under 3 months and between 3−11 months.

ResultsHospitalization rate was significantly lower in the period with vaccination programme in children under one year of age and specifically in children under 3 months (2.43 vs. 4.72 per 1000 person-years and 6.47 vs. 13.11 per 1000 person-years, respectively). The rate ratios were: 0.51 (95% CI 0.36−0.73) for children under one year of age; 0.49 (95% CI 0.32−0.75) for those younger than 3 months and 0.56 (95% CI 0.30−1.03) for those with 3−11 months. No statistically significant differences were observed in the clinical severity between both periods.

ConclusionThe introduction of the pertussis vaccination programme in pregnancy was associated with a global lower hospitalisation rate for pertussis in children under one year of age and specifically in those under 3 months of age.

La recomendación de la vacunación frente a la tosferina en embarazadas se instauró en Cataluña en febrero del 2014. El objetivo del presente estudio fue comparar la tasa de hospitalización por tosferina en niños menores de un año de edad antes y después de la implantación del programa de vacunación.

MétodosEstudio observacional y retrospectivo de pacientes menores de un año ingresados con diagnóstico de tosferina. Se comparó la tasa de hospitalización del periodo previo al programa de vacunación (2008−2013) con la del periodo con programa de vacunación (2014−2019) en el total de menores de un año y en 2 subgrupos: en menores de 3 meses y en lactantes de 3 a 11 meses.

ResultadosLa tasa de hospitalización fue significativamente menor en el periodo con programa de vacunación en menores de un año y en menores de 3 meses (2,43 vs. 4,72 por 1.000 personas-año y 6,47 vs. 13,11 por 1.000 personas-año, respectivamente). Las razones de tasas entre períodos fueron: 0,51 (IC del 95%, 0,36−0,73) para los menores de un año; 0,49 (IC del 95%, 0,32–0,75) para los menores de 3 meses y 0,56 (IC del 95%, 0,30–1,03) para los de 3–11 meses. No se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la gravedad de los cuadros clínicos de los pacientes entre ambos periodos.

ConclusiónLa instauración del programa de vacunación contra la tosferina en embarazadas se ha asociado a una menor tasa de hospitalización por tosferina de forma global en los menores de un año de edad y específicamente en los menores de 3 meses.

Pertussis (whooping cough) is a respiratory infection caused primarily by Bordetella pertussis (B. pertussis) and, to a lesser extent, by Bordetella parapertussis (B. parapertussis). Neonates and infants are at increased risk of complications. Natural and vaccine-induced immunity, especially that provided by the acellular vaccine, has a limited duration.1,2 For this reason, some strategies proposed to prevent infection of possible contacts of neonates and infants consist of substituting the tetanus and diphtheria (Td) vaccine for the reduced-antigen content diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP) in adolescents, systematic vaccination of Paediatric and Gynaecology healthcare professionals and the so-called cocoon strategy.1–4 This strategy consists of vaccinating the newborn's cohabitants and close contacts, but it entails logistical problems and its compliance has been low in the countries where it has been implemented.1,4,5

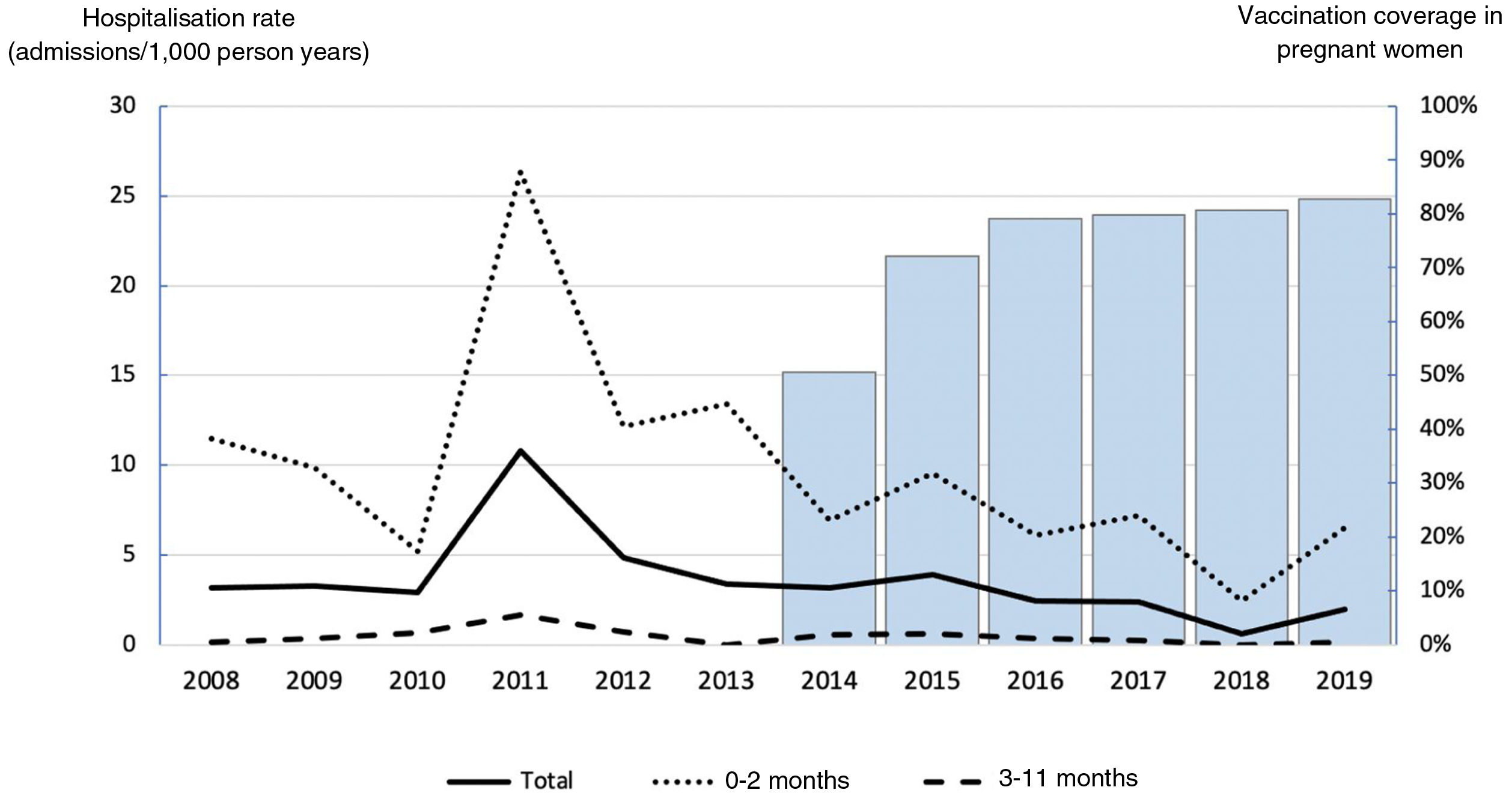

In 2011, in light of the outbreaks in the United States, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended the vaccination of pregnant women with DTaP from the 20th week of gestation, despite the fact that there was no scientific evidence of the effectiveness of this strategy.6–8 In October 2012, it recommended vaccination for each pregnancy, regardless of the time elapsed since the last dose, and in December of the same year it specified that the optimal time to administer the vaccine was between weeks 27 and 36 of gestation.9 This strategy was supported by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics.10,11 Due to the significant increase in whooping cough incidence, hospitalisation and mortality rates in Spain and Catalonia between 2010 and 2013, on 1 February 2014, the pertussis vaccination strategy with DTaP between week 27 and 36 in each pregnancy was launched in Catalonia.2,12 This measure was progressively rolled out throughout Spain and had been adopted by all the autonomous communities by January 2016.12 Pertussis vaccine coverage in pregnant women in Catalonia was 50.6% in 2014, 72.1% in 2015, 79.1% in 2016 (Agència de Salut Pública de Catalunya [Catalan Public Health Agency], unpublished data), 79.9% in 2017, 80.7% in 2018 and 82.8% in 2019 (Spanish Ministry of Health13,14). In the preliminary analysis of the impact of the vaccination programme carried out by the Centro Nacional de Epidemiología [National Epidemiology Centre]12, a decrease in the ratio of the incidence rate of children under 3 months was observed compared to children aged 3−11 months. This effect was seen earlier in the autonomous communities that had implemented the vaccination programme before June 2015.

Whooping cough is an individualised notifiable disease that is under-reported in Spain. This is because some patients do not seek medical care as the symptoms resolve spontaneously or the doctor prescribes antibiotic therapy without taking samples for microbiological study. For this reason, the number of hospitalisations due to whooping cough is a more reliable and valid indicator than the number of declared cases. The objective of this study was to compare the hospitalisation rate for whooping cough in children under one year of age before and after the implementation of the vaccination programme for pregnant women in a reference paediatric centre in Catalonia. As a secondary objective, it was analysed whether the clinical symptoms of patients under one year of age admitted for whooping cough whose mothers had been vaccinated were milder than those of the children of unvaccinated mothers.

MethodsThis was an observational, retrospective study of patients under one year of age admitted to the Hospital Infantil Vall d’Hebron [Vall d’Hebron Children’s Hospital] with a diagnosis of whooping cough that was microbiologically confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or culture over a 12-year period (January 2008–December 2019), which includes the six years prior to the introduction of the pertussis vaccination programme in pregnant women (2008−2013) and the six years after its introduction (2014−2019). Patients referred to the hospital from other health districts were excluded from the analysis. Information on the population under one year of age in the catchment area of the Hospital Infantil Vall d’Hebron was provided by the centre's Information and Innovation Management Department.

The rate of hospitalisation for whooping cough in children under one year of age in the period prior to the vaccination programme and in the period during the vaccination programme was calculated. This rate was determined for all children under one year of age and for two subgroups: infants under three months old and children aged three to 11 months. In addition, the hospitalisation rate by age group was calculated for each year. The total person years of the respective years and periods was used as denominator. The total person years in each period was calculated as the sum of the person years of the corresponding six years. The number of person years under three months was estimated as a quarter of the number of person years of the corresponding year. For each age group, the rate ratio between the period before and after the start of the vaccination programme and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated. The correlation between vaccination coverage in pregnant women in Catalonia and hospitalisation rates was studied using Spearman's correlation coefficient.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients admitted in the period prior to the vaccination programme were compared with those admitted while the programme was underway. In addition, those characteristics of the patients admitted during the vaccination programme (2014−2019) whose mothers had not received the vaccine during pregnancy were compared with those of patients whose mothers had received it. Mothers were considered to have been vaccinated when the vaccine had been administered at least 14 days before delivery. The severity parameters analysed were: admission to the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), seizure, apnoea, pneumonia, pneumothorax, pulmonary hypertension, requirement for oxygen therapy, non-invasive mechanical ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), requirement for leukoreduction, requirement for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and death.

Fisher's exact test was used to estimate the association between categorical variables, while the Mann–Whitney U test was used to estimate the association between continuous variables. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05. For the statistical analysis, Microsoft Excel version 15.12.3 for Mac, R Statistical Software version 3.5.1 for Mac15 and the OpenEpi programme, version 3.01 were used.16

The study was approved by the Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron Independent Ethics Committee (code PR_AMI_289-2012).

ResultsOver the 12 years studied (2008–2019), 143 patients under one year of age with a microbiologically confirmed diagnosis of whooping cough were admitted to the Hospital Infantil Vall d’Hebron Barcelona Hospital Campus. All cases were confirmed by PCR. Of the 143 positive cases, 131 (91.6%) were for B. pertussis and 12 (8.4%) were for B. parapertussis. In 78.3% of the patients, a respiratory sample had also been collected for culture, and in 53.6% of these B. pertussis was isolated; B. parapertussis was not isolated in any of the cultures, while 11.2% of the samples were invalid.

Of the 143 patients, 95 were admitted during the period prior to the vaccination programme (2008−2013) and 48 after the establishment of the programme (2014−2019). As can be seen in Table 1, the relative risk of hospitalisation was lower in the period with the vaccination programme compared to the period prior, and the difference was statistically significant both in those under one year of age overall and in the subgroup of children under three months, but not in the subgroup of three to 11 months. The hospitalisation rate decreased by 49% in those under one year of age and by 51% in those under three months old. Appendix B Table 1s (Annex, Supplementary material) shows the annual hospitalisation rate trend by age group, and Fig. 1 graphically represents this information together with DTaP vaccination coverage in pregnant women in Catalonia. An inverse correlation was observed between vaccination coverage in pregnant women and hospitalisation rates; this was statistically significant in the total number of children and in the subgroup of children under three months old (total children: rho=–0.73, p=0.006; under three months: rho=–0.66, p=0.02; three to 11 months: rho=–0.37, p=0.239). There were no statistically significant differences between the periods regarding the number of DTaP doses received by infants.

Rate of hospitalisation for whooping cough per 1000 person years in the period before and after the implementation of the vaccination programme, by age group.

| Total | Cases | Period 2008−2013 | Period 2014−2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 95 | 48 | ||

| 0−11 months | Cases | 95 | 48 |

| Person years | 20,141 | 19,770 | |

| Rate | 4.72 | 2.43 | |

| Rate ratio (95% CI) | 1 | 0.51 (0.36−0.73) | |

| 0−2 months | Cases | 66 | 32 |

| Person years | 5035 | 4942 | |

| Rate | 13.11 | 6.47 | |

| Rate ratio (95% CI) | 1 | 0.49 (0.32−0.75) | |

| 3−11 months | Cases | 29 | 16 |

| Person years | 15,106 | 14,828 | |

| Rate | 1.92 | 1.08 | |

| Rate ratio (95% CI) | 1 | 0.56 (0.30−1.03) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

Table 2 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients admitted in both study periods. When comparing the characteristics of the patients in the period without the programme versus the period with the programme, it was observed that 16 patients (16.84%; 26–36 weeks of gestation) vs eight patients (16.67%; 28–36 weeks of gestation) were premature; 11 (11.58%) vs five (10.42%) were admitted to the PICU; and four (4.21%) vs two (4.17%) required IMV, respectively. No patient in the hospital's catchment area died of whooping cough in the 12 years analysed. There were no statistically significant differences in the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients between the periods, which means that the patients in the period with the vaccination programme did not exhibit milder symptoms.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients admitted in the period before and after the implementation of the vaccination programme.

| Period 2008−2013 (n=95) | Period 2014−2019 (n=48) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in days, median (IQR) | 61 (43−100.5) | 68 (46.75−107.5) | 0.596 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 54 (56.84) | 26 (54.17) | 0.859 |

| Premature, n (%) | 16 (16.84) | 8 (16.67) | 1 |

| No DTaP vaccine, n (%) | 64 (67.37) | 32 (66.67) | 1 |

| 1 dose of DTaP, n (%) | 29 (30.53) | 14 (29.16) | 1 |

| 2 doses of DTaP, n (%) | 2 (2.10) | 2 (4.17) | 0.602 |

| Median days of admission (IQR) | 6 (4−8.5) | 5 (4−6) | 0.404 |

| Admission to PICU, n (%) | 11 (11.58) | 5 (10.42) | 1 |

| Median days of admission in the PICU, of those admitted to the PICU (IQR) | 5 (3−9) | 6 (4−9) | 0.728 |

| Seizure, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Apnoea, n (%) | 39 (41.05) | 16 (33.33) | 0.467 |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 9 (9.47) | 2 (4.17) | 0.335 |

| Pneumothorax, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Pulmonary hypertension, n (%) | 2 (2.10) | 0 (0) | 0.551 |

| Oxygen therapy, n (%) | 32 (33.68) | 15 (31.25) | 0.851 |

| Median days of oxygen therapy, of those who required oxygen therapy (IQR) | 5 (2−9.25) | 4 (4−5) | 1 |

| NIMV, n (%) | 1 (1.05) | 1 (2.08) | 1 |

| IMV, n (%) | 4 (4.21) | 2 (4.17) | 1 |

| Leukoreduction (exchange transfusion), n (%) | 3 (3.16) | 0 (0) | 0.551 |

| ECMO, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Death, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

DTaP: diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis vaccine; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; IQR: interquartile range; NIMV: non-invasive mechanical ventilation; PICU: Paediatric Intensive Care Unit.

Of the 48 patients admitted for whooping cough in the period with the vaccination programme, only 18 (37.5%) were children of mothers who had been vaccinated during pregnancy (Table 3). All 18 mothers had received the whooping cough vaccine between 27 and 36 weeks of gestation, in accordance with the recommendations. When comparing the characteristics of the 30 children of mothers who had not been vaccinated during pregnancy with the 18 children of vaccinated mothers, it was observed that four patients (13.33%; 28–34 weeks of gestation) vs three patients (16.67%; 34–36 weeks of gestation) were premature; three (10%) vs two (11.11%) were admitted to the PICU; and one (3.33%) vs one (5.56%) required IMV, respectively. During the period with the vaccination programme, there were no statistically significant differences in the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients between the groups, which means that the children of mothers vaccinated during pregnancy did not exhibit milder symptoms.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients admitted to hospital in the period 2014–2019 by history of vaccination of their mother during pregnancy.

| Children of unvaccinated mothers (n=30) | Children of vaccinated mothers (n=18) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in days, median (IQR) | 69.5 (47−105.75) | 67 (45.25−105.75) | 0.912 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 16 (53.33) | 10 (55.55) | 1 |

| Premature, n (%) | 4 (13.33) | 3 (16.67) | 1 |

| No DTaP vaccine, n (%) | 21 (70.00) | 11 (61.11) | 0.545 |

| 1 dose of DTaP, n (%) | 8 (26.67) | 6 (33.33) | 0.746 |

| 2 doses of DTaP, n (%) | 1 (3.33) | 1 (5.56) | 1 |

| Median days of admission (IQR) | 5 (4−5.75) | 4.5 (3−6) | 0.764 |

| Admission to PICU, n (%) | 3 (10.00) | 2 (11.11) | 1 |

| Median days of admission in the PICU, of those admitted to the PICU (IQR) | 6 (4−7.5) | 12.5 (8.25−16.75) | 0.8 |

| Apnoea, n (%) | 11 (36.67) | 5 (27.78) | 0.753 |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 2 (6.66) | 0 (0) | 0.521 |

| Oxygen therapy, n (%) | 9 (30.00) | 6 (33.33) | 1 |

| Median days of oxygen therapy, of those who required oxygen therapy (IQR) | 4 (4−5) | 4 (2.5−4.75) | 0.596 |

| NIMV, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.56) | 0.375 |

| IMV, n (%) | 1 (3.33) | 1 (5.56) | 1 |

DTaP: diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis vaccine; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; IQR: interquartile range; NIMV: non-invasive mechanical ventilation; PICU: Paediatric Intensive Care Unit.

There were also no statistically significant differences regarding the number of DTaP doses received by infants when comparing both periods and maternal vaccination history. All severe cases that required admission to the PICU, with or without IMV, were patients who had not received any DTaP doses, regardless of maternal vaccination history.

DiscussionThis study identified a decrease in the whooping cough hospitalisation rate in the period with the vaccination programme for pregnant women compared to the period prior to its implementation in the group of children under one year of age and in the subgroup of children under three months, with a reduction of 49% and 51%, respectively. The difference was not statistically significant for the subgroup aged three to 11 months, in which primary vaccination is the main protective factor.17 These data are consistent with the findings from other studies, such as that conducted by Chong-Valvuena et al.18, which found a 71% decrease in the hospitalisation rate in children under three months, but not in infants aged three to 11 months, in the province of Castellón. The greater rate decrease than in our study could be due to the fact that the vaccination coverage in pregnant women was greater (87.4%). Similarly, the study by Gentile et al.19 identified a 47.6% decrease in the hospitalisation rate in children under one year of age after the establishment of the vaccination programme for pregnant women in Argentina. This study also found that the patients had a higher mean age and that there were no deaths in the period with the programme, but the length of hospital stay and the requirement for admission to the PICU did not change. In a study conducted in California by Winter et al.,20 it was observed that the children of vaccinated mothers exhibited milder clinical symptoms and a lower risk of being hospitalised and admitted to the PICU. Length of hospital stay was also shorter and none required IMV or died. When analysing hospitalised patients in the period with the vaccination programme in our study, significantly milder clinical symptoms were not observed in the children of vaccinated mothers compared to those of unvaccinated mothers. Similarly, no differences were found in the severity of the patients' condition when comparing both periods. These results could be due to the fact that the number of patients with complications in the sample is relatively low.

In the 12-year period analysed in our study, three epidemic waves of whooping cough were recorded in Spain.12 The peak of the first epidemic wave of this period occurred in 2008, the first year included in our study, with incidence and hospitalisation rates much lower than those of the following two waves. The second epidemic wave began in 2010 and reached its peak in 2011, with an incidence rate of 1.98 per 1000 inhabitants in children under one year of age and 5.39 per 1000 inhabitants in children under three months, and a hospitalisation rate of 2.06 per 1000 inhabitants in children under one year of age and 6.66 per 1000 inhabitants in children under three months that year. The third epidemic wave was of greater magnitude than the previous two waves. It began in 2014, and in 2015 the incidence rate reached 4.57 per 1000 inhabitants in children under one year of age and 11.14 per 1000 inhabitants in children under three months, with a hospitalisation rate of 3.16 per 1000 inhabitants in children under one year of age and 9.97 per 1000 inhabitants in children under three months.12 In our study, in 2008, the peak of the first epidemic wave, we recorded a hospitalisation rate of 3.15 per 1000 inhabitants in children under one year of age and 11.45 per 1000 inhabitants in children under three months. This was followed by a downward trend until, in 2011, the peak of the second epidemic wave, we obtained the highest hospitalisation rates, recording 10.78 per 1000 inhabitants in children under one year of age and 26.35 per 1000 inhabitants in children under three months. A progressive decrease was then observed until 2014, with rates of 3.16 per 1000 inhabitants in children under one year of age and 6.90 per 1000 inhabitants in children under three months. Subsequently, there was a slight increase coinciding with the third epidemic wave, but without approaching the values of the second wave, recording 3.88 per 1000 inhabitants in children under one year of age and 9.55 per 1000 people in children under three months in 2015. The fact that the third wave was the largest in Spain and yet had the least impact in our area could be a consequence of the earlier establishment of the vaccination programme for pregnant women in Catalonia compared to the rest of the autonomous communities. A negative correlation was observed between vaccination coverage and hospitalisation rates, which was statistically significant in the total number of children and in the subgroup of children under three months old.

The hospitalisation rates in this study were higher than those recorded nationally. This may be due to the fact that the hospital is located in the Barcelona metropolitan area, where there is a high population density that favours infection in epidemic outbreaks.

The ideal time to administer the vaccine is during the third trimester of pregnancy for the optimal transfer of antibodies.2,21 The transfer of antibodies to the foetus in the third trimester is progressive as the gestational weeks progress, so preterm infants may not benefit or benefit to a lesser extent depending on the degree of prematurity. For this reason, given the threat of premature labour, it would be preferable to administer the vaccine in the second trimester of pregnancy rather than wait until the third trimester. Additionally, the vaccination of pregnant women provides immunity to the main source of infection in children under one year of age.22 Ecological observational studies that compare the incidence of whooping cough in infants of vaccinated mothers with vaccination coverage in pregnant women estimate a vaccine effectiveness greater than 75%.23–26 The pertussis vaccine, which is inactivated, has been shown to be safe for both the pregnant woman and the foetus.21,27

The latest data published on vaccination coverage across Spain refer to the year 2019. Without data from Aragon, Asturias and the Canary Islands, overall coverage was 83.6%. The autonomous communities that recorded the lowest coverage were Cantabria (55.8%) and the Balearic Islands (66.2%); the autonomous city of Ceuta registered a coverage of just 60%.14 The absence of medical follow-up during pregnancy or the omission of relevant information being given to pregnant women by the obstetrician, general practitioner or midwife could be reasons why some pregnant women would not receive the vaccine.28,29 On the other hand, pregnant women may refuse vaccination due to distrusting the safety of the vaccine in their state of pregnancy or because they do not believe prevention of this infection is necessary. As such, there are many factors that can influence vaccination coverage, which should be investigated through, for example, surveys of pregnant women, to design strategies for improvement. This was implemented at the Hospital Universitario La Paz [La Paz University Hospital],30 where it was observed that 86% of pregnant women who had not received the vaccine had not been informed about its indication and only 8% had rejected it. Also highlighted was the fact that 6% of the women were vaccinated at their own request without prior recommendation by any healthcare professional. In any case, vaccination coverage against whooping cough in pregnant women in Spain could be improved and appropriate optimisation strategies should be defined.

This study has a number of limitations, such as it having been conducted in a single centre. It is also possible that some children with whooping cough in the hospital catchment area were hospitalised in private facilities. In Catalonia, the vaccination strategy against whooping cough in pregnant women began on 1 February 2014 (a year that was included as part of the period with the vaccination programme), meaning that patients born in the first few months of that year were not exposed to the vaccination programme and, for this reason, the results of the study could underestimate the impact of the programme. It would be interesting to conduct further studies that analyse the characteristics of patients hospitalised for whooping cough whose mothers received the vaccine during pregnancy, but this group is small, probably due to the effectiveness of the vaccination programme.

In conclusion, the establishment of the vaccination programme against whooping cough in pregnant women was associated with a lower rate of hospitalisation for whooping cough in children under one year of age and in children under three months at the Hospital Infantil Vall d’Hebron in Barcelona. There were no statistically significant differences in disease severity between the children of vaccinated and unvaccinated mothers. These results are consistent with other studies and support the recommendation of many scientific societies that women be vaccinated against whooping cough in the third trimester of each pregnancy. Although high vaccination coverage has been achieved in pregnant women, diagnostic suspicion must be maintained in suspected cases, since the risk of infection will not disappear completely and whooping cough is a potentially serious infectious disease, especially in smaller infants.

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This research has not been previously presented at meetings, congresses or symposiums.