Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare aggressive neuroendocrine tumour. Prognosis is poor and metastasis frequent. Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is the principal aetiological agent, involved in 80% of cases.1 Pathogenesis is not well understood and there is no one agreed management.

We report the case of a 65-year old woman presenting in the emergency department with a circular, raised pigmented skin lesion of 2.0×2.0cm, without signs of infection, on her left forearm which had appeared following a trauma three months earlier. Physical examination revealed no evidence of axillary adenopathy.

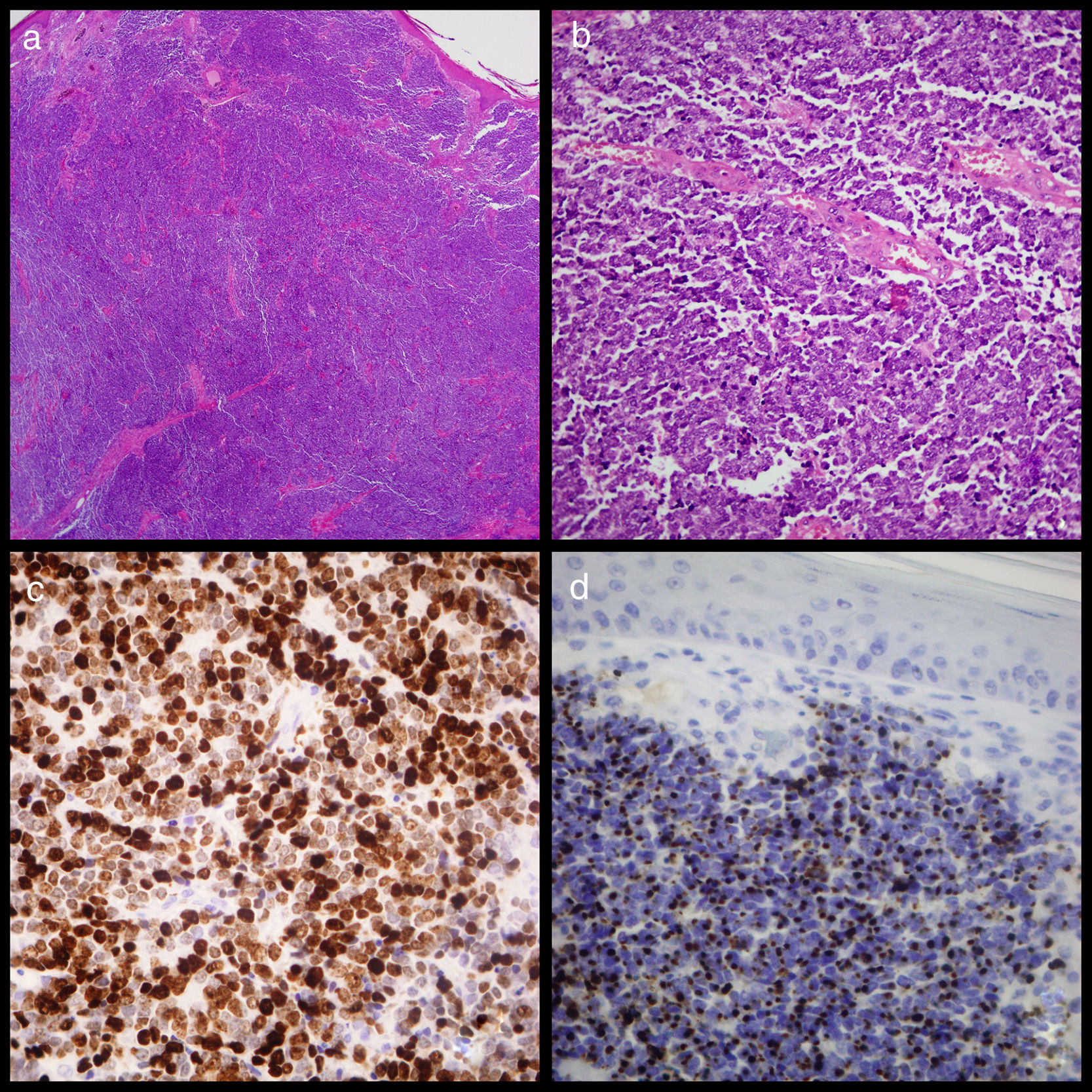

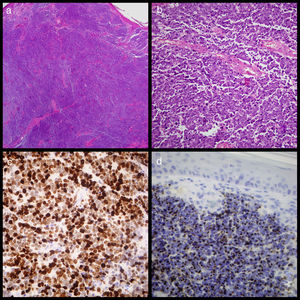

An excisional biopsy was conducted under local anaesthetic and sent to the anatomical pathology service. Examination revealed MCC with dermal proliferation and subcutaneous cellular tissue comprising small round cells with a penetrating nodular growth pattern and a rate of 7mitosis/mm2, but no vascular or perineural invasion. Immunohistochemistry staining was positive for cytokeratin-20 in the form of paranuclear “dots” throughout the tumour, 80% of which stained positive for K167, and for synaptophysin and neuronal specific erolase (Fig. 1). Because tumoral edges were found in this sample, a second more extensive excision was performed. A core needle biopsy of the left axillary ganglion proved negative. One month later a PEC-TC was conducted and no metastasis at the axillary ganglion was found.

(a) Image of cutaneous tumour which affected the dermis but not the epidermis showing the widespread growth of small round cells (haematoxylin eosin ×20). (b) Detail of the widespread growth of cells with little cytoplasm and granular chromatin nucleus with abundant mitosis and apoptosis. (c) Widespread positive Ck20 staining shown by paranuclear “dots” (Cytokeratin-20 ×400). (d). Ki67 staining showing elevated proliferation activity of around 80% (Ki67 ×400).

The first biopsy underwent genome purification (MagnaPureLC2.0, Roche) following overnight digestion with proteinaseK and trypsin. Genetic material was added to a PCR-TR mixture with MCPyV-specific primers and MGB-specific probes which targeted the VP1 gene,2 following the protocol of the laboratory. The betaglobin gene was also amplified simultaneously to test sample quality and obtain a normalised viral load should MCPyV be present.

The amplification identified 94,717,3416 (7.98log)copies/10×5cells of MCPyV.

MCC can often be confused with melanoma or lymphoma. Although the literature suggests MCC is more common in men, in this case the patient's age and the features and location of the lesion led to MCC being considered, and confirmed: patient over 50 years; painless, fast growing lesion on upper limb;3 lesion measuring more than average tumour size at diagnosis (1.7cm), alongside presence of MCPyV.

In most cases, cell transformation occurs through virus replication in mechanoreceptors4 and other cell types.5 However, the specifics of MCPyV host cell tropism(s) remain unclear, and it may be that the mechanism is mediated by oncogenes. One known trigger is UVA light although other trigger mechanisms have been identified in experimental trials,3 including, as in this case, trauma injury. That said, only one other clinical similar case has been described in the literature, in a patient who received a blow to an area affected by Bowen's disease.6

In general MCCs produced by MCPyV have a better prognosis1 when detected and diagnosed early, mortality being 30% at 2 years in such circumstances compared to 50% in patients diagnosed at advanced stages, where life expectancy can be as little as 9 months following diagnosis.7

There is no consensus in terms of treatment for MCC, although surgery is recommended at diagnosis, which may be complemented with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy.

With this patient, two excisions were carried out as the first showed the tumour edges were affected. The second was thus made employing a safety margin of 1–2cm.8 Since no metastasis was found, radiotherapy or any other therapy was delayed.

The high viral load found suggests very active viral reproduction, and could imply rapid clinical progression (as is usual with this type of tumour). It also indicates the lesion was at an early stage, as does the absence of any metastasis in the axillary ganglion, which is observed in 70% of patients at diagnosis, and thus surgery was considered sufficient treatment to eradicate the tumour.

In conclusion, in undifferentiated skin lesions, when other common pathologies can be discounted and the patient has experienced a trauma, MCC should be considered and MCPyV tested for early.

FundingThere is no external funding source.

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Central University Hospital of Asturias (HUCA).

Conflict of interestNo.