Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome is a condition described in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and whose pathogenesis is not completely clear.1 Cases have also been described in adults, in whom it is much more infrequent; the largest series published to date is of 51 cases.2

We describe a case of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults (MIS-A) and its histopathology.

The patient was a 31-year-old woman, with a history of lymphocytic meningitis of probable viral origin in 2010 and pyelonephritis in 2018. She was diagnosed in January 2021 with mild COVID-19 (positive antigen test), progressed favourably and was discharged two weeks later. Four weeks later she began with fever, headache, vomiting, mild diarrhoea and very intense pain in the right iliac fossa (RIF) for which she went to the emergency department. She was admitted on the fourth day after the onset of symptoms. At that time, she was febrile (38.5 °C), with blood pressure of 95/70 mmHg, heart rate of 96 bpm and baseline oxygen saturation of 98%. Of note were her mucocutaneous pallor, RIF pain on palpation and mild neck stiffness. Laboratory tests revealed thrombocytopenia, anaemia, lymphopenia, and elevated ESR, D-dimer, ferritin and C-reactive protein (Appendix B). An ECG showed sinus tachycardia. An urgent abdominal CT revealed mesenteric adenopathy. A SARS-CoV-2 PCR test (GeneXpert®, Cepheid) of nasopharyngeal swab was positive with a cycle threshold (Ct) >30. Lumbar puncture was normal. Blood cultures, stool cultures and urine cultures were negative. Serologies, performed with chemiluminescence immunoassay, were negative for HIV (IgM + IgG + agp24), syphilis (IgG + IgM), Toxoplasma, mumps, rubella, Coxiella, Rickettsia, Bartonella and Legionella (IgG and IgM), hepatitis C (IgG) and hepatitis B (negative HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc), while positive IgG was detected with negative IgM for CMV, EBV, parvovirus and VZV and positive IgG for SARS-CoV-2. A PCR test for Leishmania (Werfen) was negative. The autoimmunity study was normal.

The patient's condition deteriorated on the ward, with worsening clinical signs and test results (Appendix B), so treatment with piperacillin-tazobactam and doxycycline was started. On the fourth day after admission, she presented shock (BP: 70/40 mmHg; HR: 136 bpm) and severe oliguria, which did not respond to fluid therapy, so a new thoraco-abdominopelvic CT (Appendix B) was performed, which showed generalised adenopathy, especially in the root of the mesentery and RIF, mild splenomegaly, fluid in the pericardial recess, periportal oedema and mild to moderate ascites. She was admitted to the ICU and treated with piperacillin-tazobactam, linezolid, ganciclovir and liposomal amphotericin B, pending microbiological results. Suspecting septic shock of abdominal/gynaecological origin, an exploratory laparotomy was performed, which resulted in no pathological findings, except for mesenteric and mesocolic lymphadenitis. The affected lymph nodes were resected.

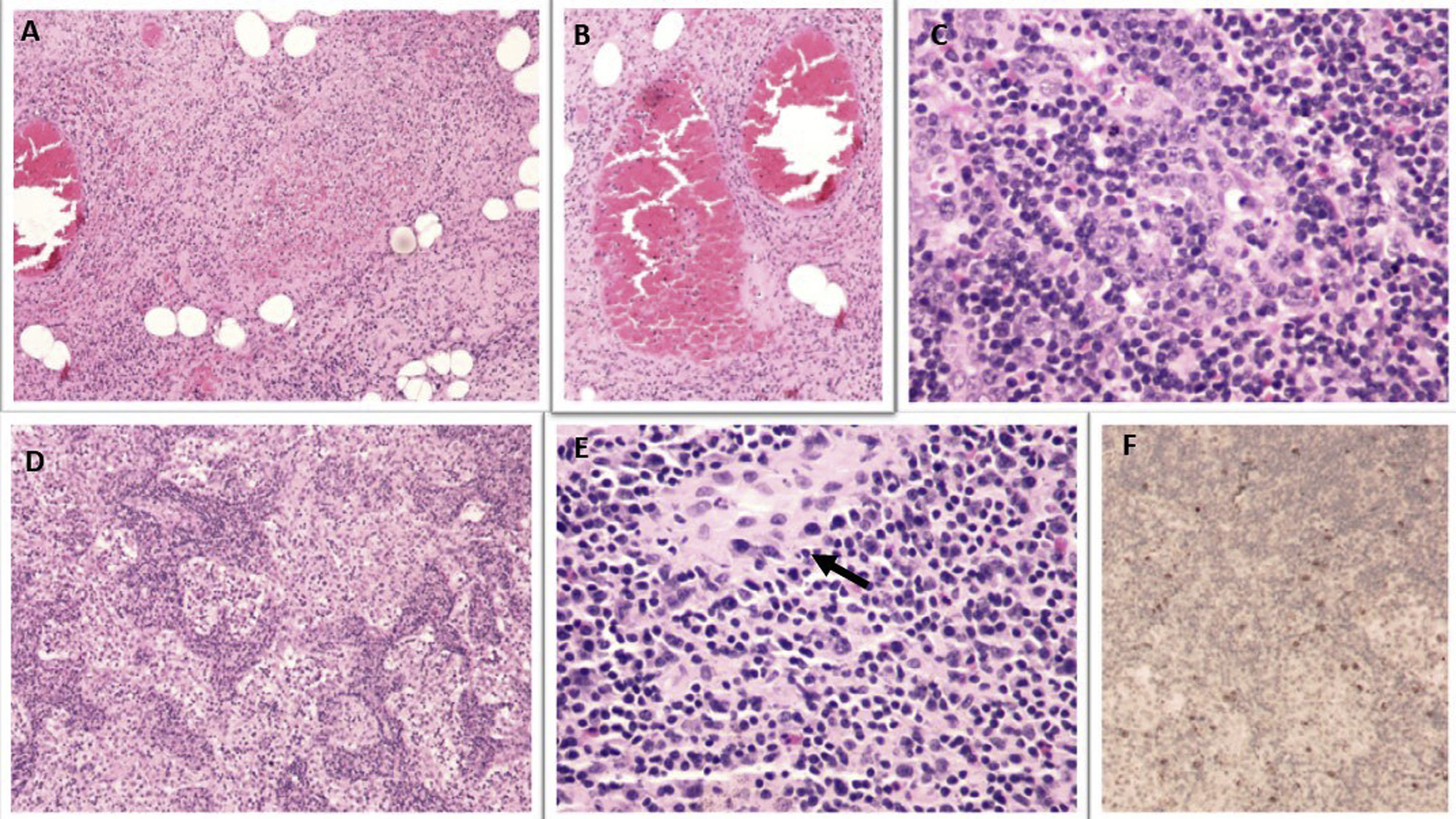

The biopsy revealed necrotising lymphadenitis and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia with extensive sinusoidal histiocytosis, with no haemophagocytosis phenomena observed (Fig. 1). A PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 in the lymph node (GeneXpert®, Cepheid) was positive. The patient was started on dexamethasone (20 mg/day), with clinical improvement; the norepinephrine was withdrawn and she was sent back to the ward. There, her vomiting and cytopenia persisted and she required the transfusion of two units of packed red blood cells due to anaemia. A bone marrow biopsy (Appendix B) showed moderate hypocellularity, with a mosaic pattern. An echocardiogram showed mild pericardial effusion and normal systolic and coronary function. Lastly, MIS-A was diagnosed, since it met the criteria for a definitive case.3 Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (2 g/kg) was added, with improved clinical signs and test results being observed. The patient was discharged with decreasing corticosteroids, acetylsalicylic acid (100 mg/day) and prophylactic enoxaparin. Six weeks later, she was asymptomatic and an echocardiogram was normal, so the acetylsalicylic acid was withdrawn.

Lymph nodes with necrotising lymphadenitis: ischaemic necrosis with necrotising vasculitis (A), periganglionic vessels with red thrombus (B), follicular hyperplasia with immunoblastic reaction (C), plasmacytosis and sinus histiocytosis (D). Presence of occasional microgranulomas (E) (arrow). Positive immunohistochemistry for SARS-CoV-2 (F).

The patient was initially managed as a case of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.4 However, she met criteria for a definitive case (level 1) of MIS-A, according to the Brighton Collaboration case definitions of 2021,3 and her response was very good to treatment with IVIG and corticosteroids. The pathogenesis of MIS-A is unknown. It could be due to an aberrant interferon response that leads to a hyperinflammatory state, with endothelial dysfunction and microangiopathy.1 Most of the cases described are in young adults from ethnic minorities5,6 two to five weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection, with predominantly cardiac and gastrointestinal involvement and a mortality rate of 3.9–11.1%.2,5,6 Cases associated with vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 have also been described.7 Treatment is extrapolated from paediatric recommendations8; the use of IVIG and corticosteroids9 is recommended, although a recent article has found no benefit from the combination in children.10

In conclusion, MIS-A should be suspected in all adults with a history of COVID-19 in the last 12 weeks who present with fever, inflammatory markers, cardiovascular involvement and extrapulmonary organ involvement, and early treatment with IVIG or corticosteroids should be established.

FundingWe confirm that no funding was received from any organisation or institution for the writing of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This case was awarded first prize in the COVID SEIMC-Gilead clinical case contest at the XXIV Congress of the Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica, held online from 5 to 11 June 2021.

Please cite this article as: Llenas-García J, Paredes-Martínez ML, Boils-Arroyo PL, Pérez-Gómez IM. Síndrome inflamatorio multisistémico del adulto asociado a SARS-CoV-2. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:407–408.