Ureaplasma urealyticum (UU) has been linked to non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) only when present at high loads and other pathogens have been excluded.1 Despite the extensive use of molecular syndromic panels targeting UU in the diagnosis of NGU, the qualitative results obtained complicate the straightforward attribution of UU as the cause of NGU. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the potential utility of the PCR cycle threshold (Ct) value in “real life” for discriminating between colonization and the potential pathogenetic involvement of this microorganism. We retrospectively analyzed all data obtained from men with suspicion of urethritis attended at the Department of Health Clínico-Malvarrosa (Valencia, Spain) between October 2018 and December 2019. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines, patients were categorized as having urethritis in the presence of urethral discharge and/or ≥2 polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL) per high-power field (1000×) in Gram staining.2 NGU was defined by the absence of Gram-negative intracellular diplococci on urethral smears and negative PCR and culture for Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG).2,3 The control group included asymptomatic subjects attending for sexually transmitted disease (STD) screening with no evidence of urethral inflammation.

All individuals provided one first-void and middle-stream urine for mycoplasma culture (Mycoplasma IST2, BioMérieux)4 and quantitative culture on BBL™ CHROMagar™ plates (Becton-Dickinson), and three urethral exudates (Dry Swabs 162C, COPAN®) for Gram staining, conventional culture on GC II agar with IsoVitaleX (Becton-Dickinson) and BBL™ Thayer-Martin selective agar (Becton-Dickinson), and a multiplex real-time PCR (RQ-SevenSTI, AB Analitica) detecting NG, UU, Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), Mycoplasma genitalium (MG), Trichomonas vaginalis (TV), Mycoplasma hominis (MH) and Ureaplasma parvum (UP). DNA extraction was carried out using the automated QIAsymphony SP extractor and the Virus/Pathogen Mini extraction kit (QIAGEN GmbH). Since it is not possible to distinguish between UU and UP by mycoplasma culture, all samples positive for UP were excluded. The Fisher's exact test and the Mann–Whitney U-test were used to compare frequencies and PCR Ct values across groups, using SPSS version 20.0 (Chicago, USA). P-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

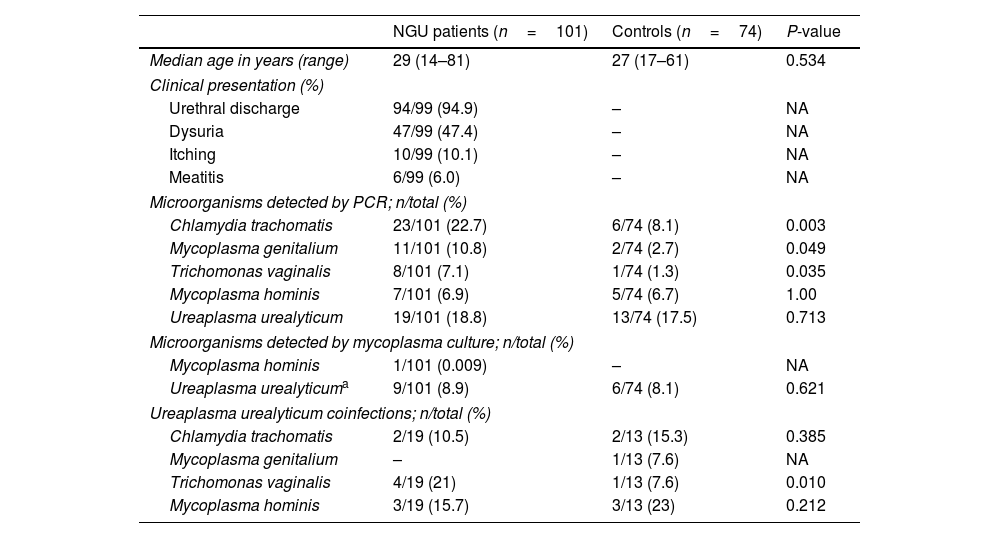

A total of 175 subjects were included, 101 patients with NGU and 74 asymptomatic controls. Demographics, clinical data and microorganisms detected in both groups are shown in Table 1. As expected, CT and MG were the most frequently pathogens found in NGU group.5 However, the frequency of detecting UU by PCR was comparable in both groups, whether they presented coinfections or if we considered those patients in whom UU was the only detected microorganism. This differs from the findings in a recent meta-analysis where the PCR detection rate of UU in suspected NGU patients was 18.31%, significantly higher than that in controls (13.7%).6 However, a direct comparison with our study is limited because some studies in the meta-analysis lacked information on co-infections with other pathogens. Notably, most studies in the meta-analysis used a cut-off of ≥5PMNL/1000×, in contrast to our study's≥2, as recommended by the CDC in high-prevalence settings.2 In our study, among the 9 of the 10 NGU patients in whom UU was the only detected microorganism and clinical data was available, all but one patient received empirical or targeted antimicrobial therapy (macrolides, tetracyclines, or quinolones) and resolved their clinical symptoms. These findings may suggest the casual involvement of UU in our study. However, a notable limitation of our series is the inability to rule out other non-cultivable pathogens contributing to NGU such as herpesvirus and adenovirus.5 In 2018, the Editorial Board of the European Guidelines for STD recommended antimicrobial treatment for men diagnosed of NGU attributable to UU only when the bacterial load is ≥103 genome equivalents/ml of urine. In our study, the median Ct value for UU was similar (P=0.41) in cases (29; IQR, 28–33) and controls (31; IQR, 28–35), irrespective of whether other microorganisms were co-detected (28; IQR, 26–32) or not (32; IQR, 28–35). In conclusion, these findings suggest that Ct values do not correlate with clinical presentation and do not endorse the clinical utility of PCR Ct values in inferring the potential causal involvement of UU in NGU in a real-life setting. The limitations in ruling out other non-cultivable pathogens contributing to NGU emphasizes the need for further research in understanding the role of UU in urethritis.

Demographics and microorganisms detected in NGU and control group.

| NGU patients (n=101) | Controls (n=74) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (range) | 29 (14–81) | 27 (17–61) | 0.534 |

| Clinical presentation (%) | |||

| Urethral discharge | 94/99 (94.9) | – | NA |

| Dysuria | 47/99 (47.4) | – | NA |

| Itching | 10/99 (10.1) | – | NA |

| Meatitis | 6/99 (6.0) | – | NA |

| Microorganisms detected by PCR; n/total (%) | |||

| Chlamydia trachomatis | 23/101 (22.7) | 6/74 (8.1) | 0.003 |

| Mycoplasma genitalium | 11/101 (10.8) | 2/74 (2.7) | 0.049 |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | 8/101 (7.1) | 1/74 (1.3) | 0.035 |

| Mycoplasma hominis | 7/101 (6.9) | 5/74 (6.7) | 1.00 |

| Ureaplasma urealyticum | 19/101 (18.8) | 13/74 (17.5) | 0.713 |

| Microorganisms detected by mycoplasma culture; n/total (%) | |||

| Mycoplasma hominis | 1/101 (0.009) | – | NA |

| Ureaplasma urealyticuma | 9/101 (8.9) | 6/74 (8.1) | 0.621 |

| Ureaplasma urealyticum coinfections; n/total (%) | |||

| Chlamydia trachomatis | 2/19 (10.5) | 2/13 (15.3) | 0.385 |

| Mycoplasma genitalium | – | 1/13 (7.6) | NA |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | 4/19 (21) | 1/13 (7.6) | 0.010 |

| Mycoplasma hominis | 3/19 (15.7) | 3/13 (23) | 0.212 |

–: negative; NA: not applicable.

María Jesús Castaño, María Jesús Alcaraz and Eliseo Albert: data curation and analysis. María Jesús Castaño and David Navarro: study design and manuscript drafting. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

FundingThe authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no relevant competing interest to disclose about this work.

Eliseo Albert holds a Juan Rodés Contract (JR20/00011) funded by the Carlos III Health Institute (co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, ERDF/FEDER).