This was a case of a 62-year-old patient with a medical history of diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, ischaemic heart disease and no haematologic history of interest. He reported a stay in a country with a tropical climate (Costa Rica) more than 10 years previously, without recent travel. He was admitted in October 2020 for a study of pancytopoenia, constitutional syndrome of two months' evolution, fever of unknown origin and digital ulcer of torpid evolution. A bone marrow aspiration was performed, confirming the initial suspicion of acute leukaemia with dendritic differentiation: blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Cytogenetics and karyotype, normal. Molecular markers of adverse prognosis in a massive sequencing study.

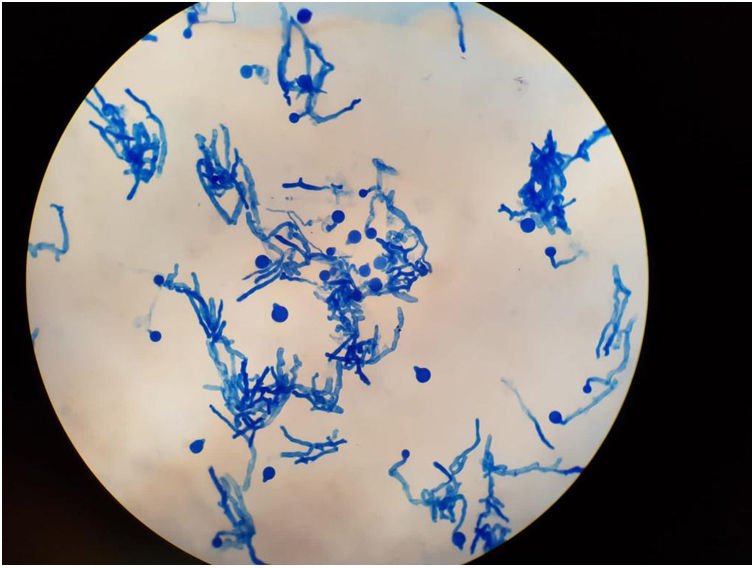

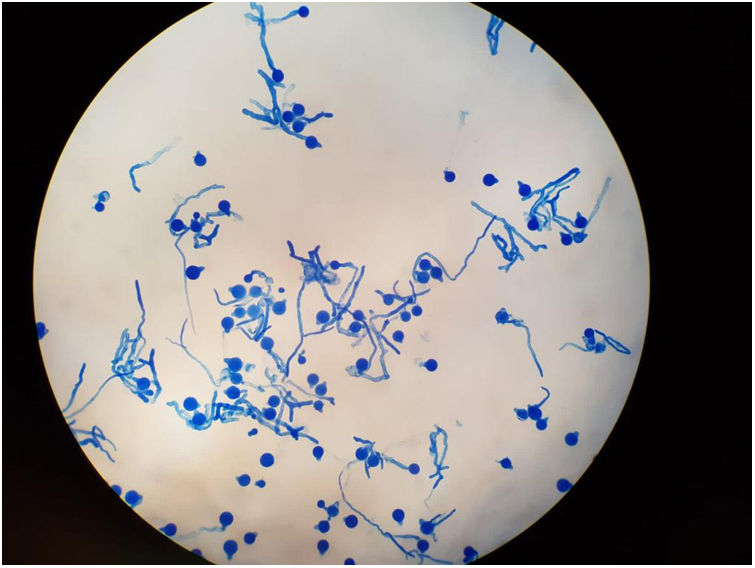

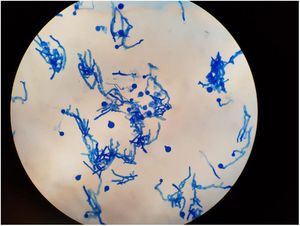

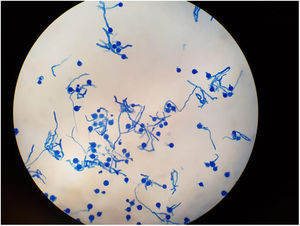

Clinical courseFollowing diagnostic confirmation, the patient presented clinical worsening, palpebral oedema and erythema, persistent fever despite broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy for gram-positive and -negative bacteria and coverage for filamentous fungus, with increasing parameters of severe infection and negative microbiological results (absence of germ growth documented in negative blood cultures, urine cultures and serial galactomannans). In view of the frank disease progression, and following a risk-benefit assessment with the absence of microbiological data at that time, the decision to initiate chemotherapy treatment was taken. After 24 h, the patient presented severe acute respiratory failure, septic shock, digital ulcer necrosis and proptosis of the right eyeball, requiring transfer to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for support with vasoactive drugs, continuous veno-venous haemofiltration and invasive mechanical ventilation by means of orotracheal intubation. In the bronchial aspirate performed during the intubation process, the Microbiology Service observed the growth of a filamentous fungus, probably of the mucorales family, informing a preliminary result. At that time, antifungal coverage was reinforced by administering dual therapy with intravenous and inhaled liposomal amphotericin B together with intravenous caspofungin. After six days in the ICU, the patient presented multiple organ failure and eventually died. Post mortemmicrobiological isolation of Zigomycete (subphylum entomophthoromycotina): Conidiobolus coronatus was confirmed (Figs. 1 and 2) in bronchial aspirate, probably causing invasive pulmonary fungal infection and rhinofacial cellulitis with invasion of paranasal sinuses and orbital fossa.

Conidiobolomycosis occurs in humans after the inhalation of spores that colonise the nasal mucosa and can penetrate the facial subcutaneous tissue and nasal sinuses in immunocompetent patients1,2. It is typically a tropical disease that requires high levels of moisture for growth and development. However, the presence of this microorganism has been described in environmental samples from cold-climate countries in northern Europe. It predominates in male patients, 10 to 13.

Clinically, it is characterised by the appearance of progressive submucosal or subcutaneous nodular lesions predominantly located in the nostrils, orbit and face. In more severe cases, and particularly in immunocompromised patients, it can course with disseminated infection symptoms4.

The diagnosis of C. coronatus infection is performed by histological examination of a biopsy of the lesion and culture4. The most characteristic finding, while not pathognomonic, is the visualisation of wide and transparent hyphae, which are poorly septated and enveloped in eosinophilic material (Figs. 1 and 2). The isolation of this fungus in the culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar with chloramphenicol confirms the diagnosis3.

Optimal treatment in severe cases is based on the use of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B or the combination of terbinafine with a triazole for 12 months and assessment of exeresis of the affected tissue4.

In many cases, microbiological identification takes 1–4 weeks to culture, which in immunocompromised patients can involve a particular relevance and higher mortality derived from a late start of treatment in cases in which diagnostic suspicion is low, so an adequate clinical history is necessary in which to ask about possible stays in areas of high incidence (Asia, Africa and South America especially)5. In our case, the only notable epidemiological antecedent was the stay in Costa Rica.

About 10 cases of invasive infection caused by this microorganism in immunosuppressed patients have been reported in the literature, none of them in Spain. Most of them presented disseminated infections with multiple organ involvement, hence it is important to conclude that minimising the time elapsed between suspicion and diagnostic confirmation is very important in reducing mortality resulting from delayed targeted treatment2.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.