Actinotignum schaalii (A. schaalii) (previously Actinobaculum schaalii) is a small, straight or slightly-curved, gram-positive coccobacillus that is facultatively anaerobic. Although considered part of the urinary microbiota, it is also the cause of urinary tract infections (UTIs) that are often under-diagnosed due to its slow growth in culture media and the required incubation conditions.1

We present a case of UTI due to A. schaalii in a patient allergic to beta-lactams: an 88-year-old woman with a history of ureteral stenosis, hydronephrosis, urinary incontinence, and recurrent urinary tract infections (3−4UTIs/year). She saw her primary care doctor due to dysuria and frequent urination of one week's evolution, without associated fever. Physical examination revealed no pathological findings, and bilateral fist-percussion was negative. Leukocyturia and bacteriuria were observed in the urine test using a dipstick, and the nitrite test was negative. The sample sent for urine culture was analysed by flow cytometry (Sysmex UF-1000i®) and detected leukocyturia (1,137WBC/μL) and bacteriuria (2,684BACT/μL). Subsequently, BD CHROMagar Orientation Medium was inoculated with 1μl of urine and incubated aerobically at 35±2°C; with no evidence of growth at 24h. Due to the patient's history and the high bacteriuria detected by cytometry, much higher than 500BACT/μl –the cut-off point for our centre to inoculate urine from women from primary care–, the sample was cultured on BD Brucella Blood Agar with Hemin and Vitamin K1 and on BD Chocolate Agar (GC II Agar with IsoVitaleX) at 35–37°C, in anaerobiosis and with 5% CO2, respectively. After 48h of incubation, small greyish nonhaemolytic colonies were isolated in both media, although with better growth in Brucella agar, counting >100,000CFU/mL. Identification was carried out by mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF®, Bruker Daltonics), with the result of A. schaalii with score >2. The antibiogram was performed using gradient diffusion strips (Liofilchem®) in Brucellaagar and anaerobiosis. According to CLSI 2021 criteria for Streptococcus spp.2 and EUCAST 2021PK/PD,3 the strain was sensitive to beta-lactams: ampicillin, MIC 0.032μg/mL; amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, MIC 0.125μg/mL. Additionally, according to CLSI 2021 criteria for Staphylococcus spp., it was sensitive to vancomycin (MIC 0.125μg/mL) and linezolid (MIC 1μg/mL); and resistant to ciprofloxacin (MIC 4μg/mL) and co-trimoxazole (MIC 4/76μg/mL).

Given the complexity of the case, the primary care doctor had an interconsultation with the Infectious Diseases Department, after which it was decided, taking into account the possibility of outpatient management in a stable patient with reduced mobility, to start treatment with oral linezolid 600mg/every 12h for 14 days, with follow-up blood tests after a week to assess secondary haematological toxicity. After completing the antibiotic regimen, the symptoms ceased, the control urine culture was negative for A. schaalii and the patient had no adverse effects secondary to treatment.

In a recent review of A. schaalii, Lotte et al. counted 172 published cases, including 121 UTI cases (70%) and 33 (19%) bacteraemia cases; being isolated, mainly, in elderly patients (>60 years), with predisposing factors such as: recurrent UTIs or underlying urological pathology.4

Regarding identification, currently MALDI-TOF® mass spectrometry is the usual technique of choice due to its speed and accuracy compared to 16S RNA gene sequencing. On the other hand, it is noteworthy that among the most utilised methods of MALDI-TOF®, only Microflex Biotyper (Bruker Daltonics) offers good identification of A. schaalii.5

Although there are no specific recommendations on how to perform and interpret the Actinotignum spp. antibiogram, it is usually considered sensitive to all commonly used beta-lactams; as well as vancomycin, nitrofurantoin, linezolid and gentamicin; being generally resistant to quinolones (ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin) and co-trimoxazole.6 There are also no treatment guidelines for infections caused by A. schaalii. Clinical and microbiological evolution is usually favourable in patients treated with beta-lactams (amoxicillin, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone) for at least 14 days; relapses have been described with shorter treatments.7 In the case described, linezolid was successfully used, constituting a new and effective treatment alternative in UTI due to A. schaalii; especially in those patients who cannot receive beta-lactams.

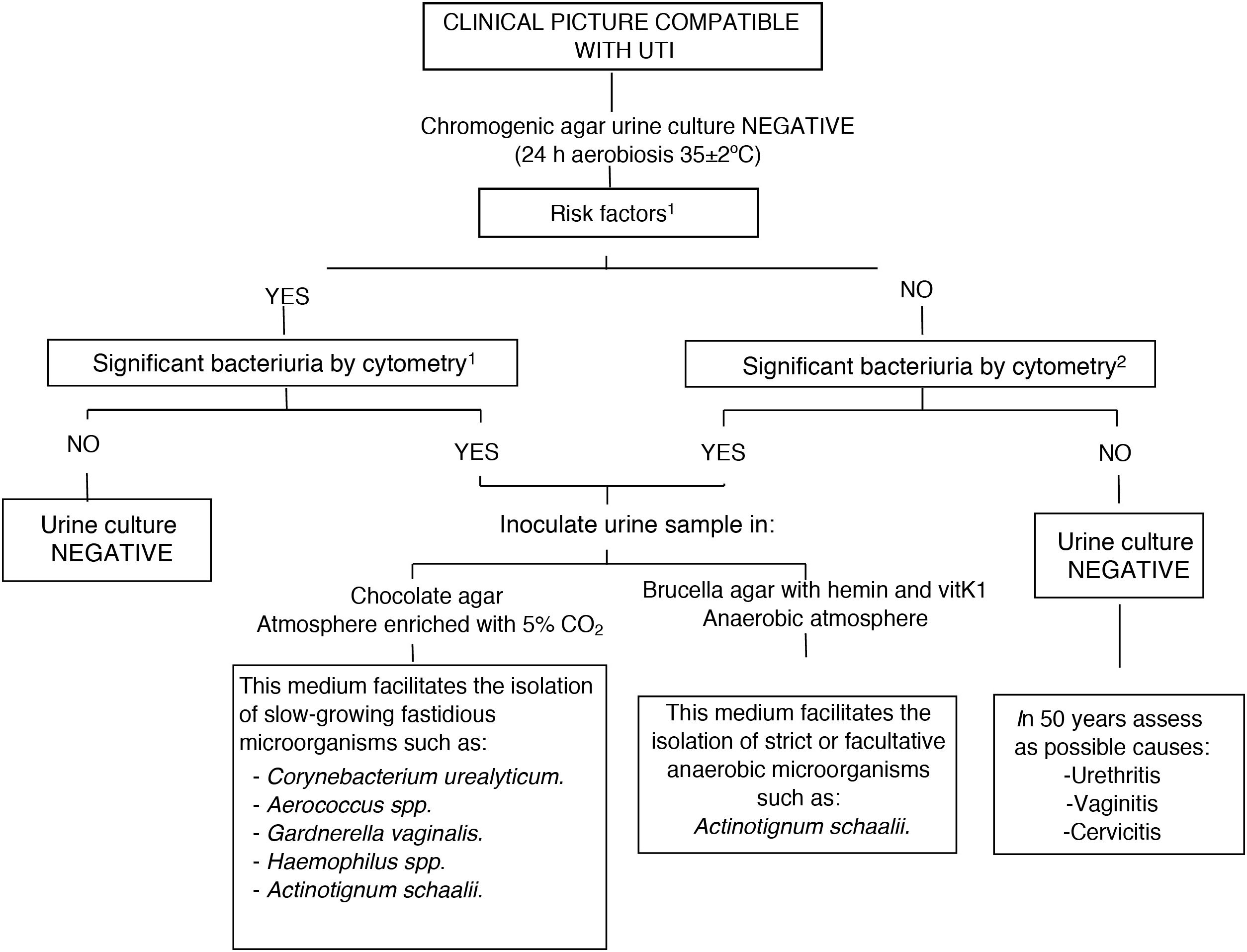

Based on our experience, between January 2019 and May 2021, 42 strains of A. schaalii were isolated in urine samples (a single isolate per patient) following a simplified algorithm (Fig. 1). The mean number of bacteria detected by cytometry was 7651.67 BACT/μl. The mean age of the patients was 81.3 years, with a predominance of women (29 women vs.13 men). After reviewing the medical records, the finding of A. schaalii was clinically significant in 27 patients (64.3%), in whom it was explicitly stated as a diagnosis of UTI due to A. schaalii. Of the 27 isolates in which an antibiogram was performed: 27 were sensitive to ampicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; nine were sensitive to cotrimoxazole and one to norfloxacin.

Diagnostic algorithm in negative urine cultures from Hospital Universitario de Basurto [Basurto University Hospital]. 1Risk factors: urinary incontinence, catheterisation, benign prostatic hyperplasia, bladder tumour, neurogenic bladder, ureteral stenosis….

2Screening cut-off points at the Hospital Universitario de Basurto:

Outpatient ♀ ≥500 BACT/μl, ♂ ≥100 BACT/μl and children ≥100 BACT/μl.

Admitted patient/Emergency department: ≥50 BACT/μl.

Some authors8,9 consider that not systematically performing a microscopic examination (Gram stain) on urine samples, and the use of selective media to improve process management (CLED agar, MacConkey or chromogenic agars) incubated 24h aerobically, increases the probability of false negative urine cultures in cases of UTI due to fastidious bacteria such as A. schaalii; which delays the administration of an effective treatment. However, in our opinion, routine Gram staining of all urine samples is not feasible given the high number of urine samples processed daily and the lack of human resources.

Therefore, like other authors4 we propose the following algorithm (Fig. 1): if the microbiology laboratory has flow cytometry technology, we propose its use as a screening method prior to urine culture to quantify the number of bacteria present in the urine, and, in the event of a negative culture and high bacteriuria, inoculating the sample in additional culture media, such as chocolate agar and Brucellaagar in prolonged incubation (48h) to rule out uncommon and challenging uropathogens. If flow cytometry is not available in the centre, Gram staining could be useful in certain cases of recurrent UTI in patients with underlying urological pathology or chronic sterile pyuria, inoculating the urine in special media based on the morphology observed in Gram stain.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Ramos IS, Angulo-López I, M. de la Peña-Trigueros M, Tuesta-del Arco JLD. Utilidad de la citometría de flujo en el diagnóstico de infecciones del tracto urinario por microorganismos exigentes: a propósito de un caso de cistitits aguda por Actinotignum schaalii, Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:580–581.

![Diagnostic algorithm in negative urine cultures from Hospital Universitario de Basurto [Basurto University Hospital]. 1Risk factors: urinary incontinence, catheterisation, benign prostatic hyperplasia, bladder tumour, neurogenic bladder, ureteral stenosis…. 2Screening cut-off points at the Hospital Universitario de Basurto: Outpatient ♀ ≥500 BACT/μl, ♂ ≥100 BACT/μl and children ≥100 BACT/μl. Admitted patient/Emergency department: ≥50 BACT/μl. Diagnostic algorithm in negative urine cultures from Hospital Universitario de Basurto [Basurto University Hospital]. 1Risk factors: urinary incontinence, catheterisation, benign prostatic hyperplasia, bladder tumour, neurogenic bladder, ureteral stenosis…. 2Screening cut-off points at the Hospital Universitario de Basurto: Outpatient ♀ ≥500 BACT/μl, ♂ ≥100 BACT/μl and children ≥100 BACT/μl. Admitted patient/Emergency department: ≥50 BACT/μl.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/2529993X/0000004000000010/v2_202212170724/S2529993X22001381/v2_202212170724/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)