The frailty present at hospital admission and the stressors to which patients are subjected during their stay may increase dependency at hospital discharge.

ObjectivesTo assess the predictive validity of the Clinical Frailty Scale-España (CFS-Es) on increased dependency at 3 and 12 months (m) after hospital discharge.

MethodologyMulticentre cohort study in 2020–2022. Including patients with >48 h stay in intensive care units (ICU) and non-COVID-19. Variables: pre-admission frailty (CFS-Es). Sex, age, days of stay (ICU and hospital), dependency on admission and at 3 m and 12 m after discharge (Barthel index), muscle weakness (Medical Research Council Scale sum score <48), hospital readmissions. Statistics: descriptive and multivariate analysis.

Results254 cases were included. Thirty-nine per cent were women and the median [Q1–Q3] age was 67 [56–77] years. SAPS 3 on admission (median [Q1–Q3]): 62 [51–71] points.

Frail patients on admission (CFS-Es 5–9): 58 (23%). Dependency on admission (n = 254) vs. 3 m after hospital discharge (n = 171) vs. 12 m after hospital discharge (n = 118): 1) Barthel 90–100: 82% vs. 68% vs. 65%. 2) Barthel 60–85: 15% vs. 15% vs. 20%. 3) Barthel 0–55: 3% vs. 17% vs. 15%.

In the multivariate analysis, adjusted for the variables recorded, we observed that frail patients on admission (CFS-Es 5–9) are 2.8 times (95%CI: 1.03–7.58; p = 0.043) more likely to increase dependency (Barthel 90–100 to <90 or Barthel 85–60 to <60) at 3 m post-discharge (with respect to admission) and 3.5 times (95%CI: 1.18–10.30; p = 0.024) more likely to increase dependency at 12 m post-discharge. Furthermore, for each additional CFS-Es point there is a 1.6-fold (95%CI: 1.01–2.23; p = 0.016) greater chance of increased dependency in the 12 m following discharge.

ConclusionsCFS-Es at admission can predict increased dependency at 3 m and 12 m after hospital discharge.

La fragilidad presente al ingreso hospitalario y los estresores a los que son sometidos los pacientes durante su estancia, pueden incrementar la dependencia al alta del hospital.

ObjetivosEvaluar la validez predictiva de la Clinical Frailty Scale-España (CFS-Es) sobre el incremento de la dependencia a 3 y 12 meses (m) del alta hospitalaria.

MetodologíaEstudio de cohorte multicéntrico en 2020–2022. Incluidos pacientes con estancia >48 h en unidades de cuidados intensivos (UCI) y no COVID-19. Variables: fragilidad previa al ingreso (CFS-Es). Sexo, edad, días de estancia (UCI y hospital), dependencia al ingreso y a 3 m y 12 m del alta (Índice de Barthel), debilidad muscular (Medical Research Council Scale sum score <48), reingresos hospitalarios. Estadística: descriptiva y análisis multivariante.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 254 casos. El 39% fueron mujeres y la mediana [Q1–Q3] de edad fue de 67 [56–77] años. SAPS 3 al ingreso (mediana [Q1–Q3]): 62 [51–71] puntos.

Pacientes frágiles al ingreso (CFS-Es 5–9): 58 (23%). Dependencia al ingreso (n = 254) vs. 3 m del alta hospitalaria (n = 171) vs. 12 m del alta hospitalaria (n = 118): 1) Barthel 90–100: 82% vs. 68% vs. 65%. 2) Barthel 60–85: 15% vs. 15% vs. 20%. 3) Barthel 0–55: 3% vs. 17% vs. 15%.

En el análisis multivariante, ajustado por las variables registradas, observamos que los pacientes frágiles al ingreso (CFS-Es 5–9) tienen 2,8 veces (IC95%: 1,03–7,58; p = 0,043) más posibilidades de incrementar la dependencia (Barthel 90–100 a <90 o Barthel 85–60 a <60) a 3 m del alta (respecto al ingreso) y 3,5 veces (IC95%: 1,18–10,30; p = 0,024) más posibilidades de incrementar dependencia a 12 m del alta. Además, por cada punto adicional de CFS-Es se multiplica por 1,6 (IC95%: 1,01–2,23; p = 0,016) la posibilidad de incrementar la dependencia en los 12 m siguientes al alta.

ConclusionesLa CFS-Es al ingreso puede predecir un incremento de la dependencia a los 3 m y 12 m del alta del hospital.

Frailty assessment is a concept developed to describe the degree of deterioration of the organism over time. The initial application is for elderly patients. Many authors have evaluated the predictive validity of the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) on mortality or discharge of the elderly to a long-term facility after hospital admission. Few authors have assessed the predictive validity of this scale on the increase in dependency.

What it contributesIn this article we evaluate the predictive validity of the Spanish version of the CFS, the Clinical Frailty Scale-España (CFS-Es), on the increase in dependency in patients who have been admitted to adult intensive care, regardless of age and not only in the elderly. The results highlight the possibility of using these scales, to be able to evaluate the fragility of all patients admitted to intensive care, and to be able to predict how it will affect their dependency upon discharge from the hospital.

According to the results obtained, applying the CFS-Es to patients will allow us to detect vulnerable or frail patients. In this way, we will be able to prioritise and plan care aimed at avoiding loss of capacity in these patients, who are more susceptible to further deterioration.

IntroductionFrailty can be defined as a syndrome that includes systemic alterations, comorbidities, physiological deterioration and deregulation of metabolic balance.1 It is not a disease, but the description of the degree of deterioration of our body due to age.2 Frailty is therefore a concept developed by geriatricians, which is associated with age, but has also been related to chronic diseases, so it could manifest itself in younger patients, who could be more susceptible to critical illnesses and multiple organ failure, as a consequence of these diseases.3

Exposure of a frail individual to stress factors increases the risk of disability or other adverse outcomes, such as hospitalisation or death.4 Frail patients are at greater risk of prolonged hospital stays, admission to Intensive Care Units (ICU) and, therefore, having their quality of life affected upon discharge from the hospital.5,6 Frailty, along with other factors such as age, comorbidities, length of mechanical ventilation, stay in the ICU, delirium, low mobility of patients and ICU acquired muscle weakness (ICU-AW), has been associated with the so-called post-ICU síndrome.7–9 This syndrome can affect 64% of surviving ICU patients 3 months after hospital discharge and up to 56% of survivors at one year,7 and is also the cause of readmission or death in 47% of patients during the first year period after discharge.10 Early detection of the frail patient could favour the prevention of the syndrome.

Up to 67 instruments have been defined to evaluate frailty11 and the most used and referenced, both in elderly and critically ill patients, is the Clinical Frailty Scale, (CFS) developed and validated by Rockwood et al.12 in the second Canadian study on health and aging [Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA)] in 2005. To this scale, initially with 7 levels, the authors added two more levels in 2007. In addition, as of 2020, individuals who were at level 4 went from being vulnerable to being considered patients with very mild frailty, although the definition of the level remained unchanged.13

After a process of adapting the CFS to Spanish, through translation, back-translation, concordance and pilot testing, the Clinical Frailty Scale-España14 ((CFS-Es) was obtained. Continuing with the validation process, the objective of this study is to evaluate the predictive validity of the Spanish version of the Clinical Frailty Scale on the increase in dependency, after discharge from the hospital, of patients admitted to the ICU.

MethodologyMulticentre prospective observational study, in which a total of 5 ICUs participated. Those patients of legal age who consented to participate, with a stay in the ICU greater than 48 h and who were admitted between January 2020 and December 2022 were included. Patients with suspected imminent death or with COVID-19 were not included.

The 5 participating units belonged to public university hospitals of the Spanish health system network, from 4 autonomous communities (Asturias, Canary Islands, Catalonia and Madrid). Four of these hospitals are large (more than 500 beds) and one is medium (between 200 and 500 beds). Three units are multipurpose, one surgical and the other cardiac. Only one unit had an early mobilization protocol and 2 units had a physiotherapist on the ICU staff.

Patients included in the study were followed up during their stay in the ICU, in the hospital, and up to 1 year after hospital discharge, through telephone reviews at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months.

Study variablesUpon admission to the ICU, the demographic characteristics of the patients (age, sex, weight, and height) were recorded. Admissions, up to a year before, to an acute care hospital and/or an ICU were also recorded. The baseline status of dependency, prior to hospital admission, was assessed with the Barthel index15,16 and frailty with the Clinical Frailty Scale-España (CFS-Es).14 Comorbidities were recorded, with the Charlson comorbidity index,17 and the level of severity, with the Simplified Acute Physiology Score 318 (SAPS 3).

The maximum and minimum level of sedation/agitation, measured with the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS)19 was recorded daily during the ICU stay; pain was measured with the numerical scale or Pain Indicator Behaviour Scale (BPS)20; presence of delirium, was assessed with the Confusion Assessment Method in Intensive Care Units (CAM-ICU)21; active mobilisation out of bed was measured with the intensive mobility scale (IMS-Es ≥ 4)22; evolution of organ failure was measured using the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (SOFA),23 together with the need for invasive mechanical ventilation.

Starting from when the patient was conscious and cooperative, muscle strength was measured weekly, using the Medical Research Council Scale sum score, to detect signs of weakness (MRC-SS < 48), following the Hermans protocol,24 until discharge from the hospital.

After discharge from the hospital, in the telephone reviews, weight and admissions in the previous 3 months to an acute care hospital and/or an ICU were recorded. Also, the level of dependency (Barthel index15) and level of frailty (CFS-Es) were evaluated at the time of the call.

Both the data recorded at admission, as well as the data recorded in telephone follow-ups, were obtained from the patient himself or from a close family member. If the informant was a family member, the data were subsequently verified with the patient themselves, except in those with cognitive impairment.

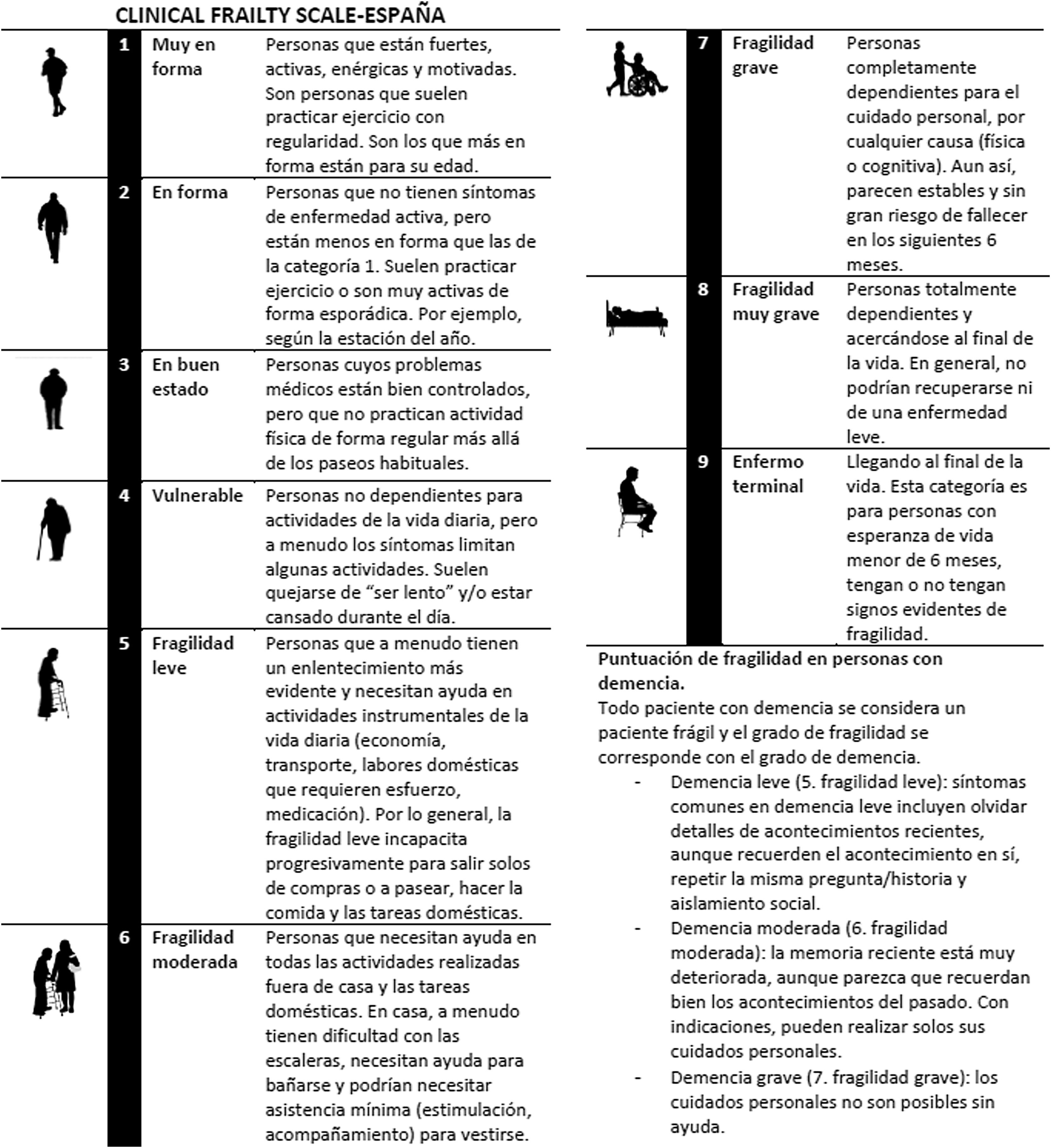

Description of the toolsAfter obtaining permission from the authors of the Clinical Frailty Scale12,13 and a cross-cultural adaptation process, Arias-Rivera et al. obtained the Clinical Frailty Scale-España14 in 2020. This scale evaluates the functional state of the person in 9 levels, through their physical activity or training, mobility and basic and instrumental skills. The higher the level at which the patient is placed, the greater the fragility. Levels 1–3 include patients considered non-frail, level 4 includes those considered vulnerable, and levels 5–8 include frail patients. Terminal patients with a life expectancy of less than 6 months are placed at level 9. The description of each of the levels can be seen in Fig. 1.

Clinical Frailty Scale-España.

Adapted from the Spanish with permission from the copyright holder.12

The Barthel index15,16 is an instrument that assesses the physical function or dependence of patients with respect to some basic activities. Each activity is assigned scores of 0, 5, 10 or 15. The global range varies between 0 (completely dependent) and 100 (completely independent). In the present study, 3 strata have been considered to evaluate the increase in dependence. The first stratum was determined at 90–100 points, based on the consensus document of the Spanish Ministry of Health,25 on prevention of frailty in older people. In this document, an early detection and intervention strategy is established in the population with Barthel equal to or greater than 90. In the second stratum, patients with moderate dependence (60–85 points) were considered and the third stratum included patients with Barthel less than 60, as they are the patients with the greatest dependence on basic activities.16

Statistical analysisThe variables are described as median and interquartile range [Q1–Q3] or mean and standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables (depending on their parametric behaviour). For qualitative variables, absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies are used. The normality of the variables was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. P < .05 is considered statistically significant and the 95% confidence interval is provided for the tests used.

The comparison between non-frail patients (CFS-Es 1–4) and frail patients (CFS-Es 5–9), upon admission or after hospital discharge was carried out with the T test or Mann–Whitney U test, according to normality of quantitative variables and qualitative variables with the Chi square test.

To evaluate the predictive validity of the CFS-Es scale with respect to the increase in dependency after discharge from the hospital, a multivariate analysis was carried out where the significant variables were included in the univariate or if a variable was considered of interest for our dependent variable, there was an increase in dependency. An increase in dependency was considered if we went from Barthel 90–100 to Barthel <90 or from Barthel 85–60 to Barthel <60. A logistic regression model was proposed after verifying that the resulting model included a sufficiently high number of cases to apply this regression model. Furthermore, the dependent variable meets the categorical condition, there is no significant multicollinearity between the independent variables, the relationship is linear in the logit, and the data are independent. These findings support the appropriate application of multiple logistic regression in data analysis.

For data analysis, the statistical package SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 23.0 IBM Corp; USA) and the Stata® program (version IC14, StataCorp LLC; USA) were used.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the ethics committee of the reference hospital (CEIm19/42) and by the ethics committees or viability commissions of the collaborating centres (according to the criteria of each centre). Patient consent was required for inclusion in the study, or that of the patient’s closest relative, in the event that they were unable to give their consent personally.

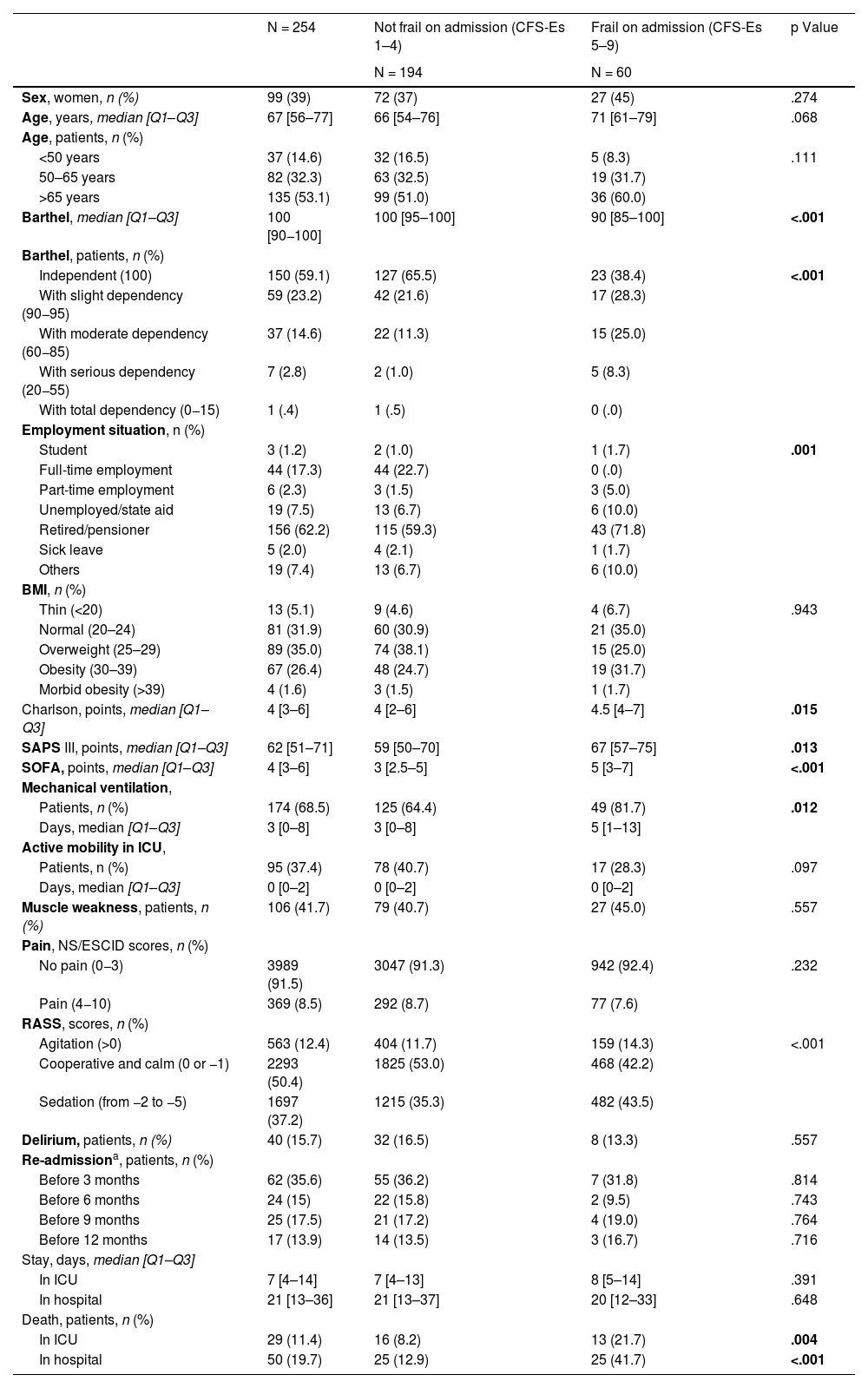

ResultsTwo hundred and fifty-four patients were included. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics upon admission to the ICU. The median age [Q1–Q3] was 67 [56–77] years and 119 patients (46.9%) were younger than 65 years. We observed that frail patients had higher levels of dependency, more comorbidities, and greater severity upon admission to the ICU.

Population descriptions.

| N = 254 | Not frail on admission (CFS-Es 1–4) | Frail on admission (CFS-Es 5–9) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 194 | N = 60 | |||

| Sex, women, n (%) | 99 (39) | 72 (37) | 27 (45) | .274 |

| Age, years, median [Q1–Q3] | 67 [56–77] | 66 [54–76] | 71 [61–79] | .068 |

| Age, patients, n (%) | ||||

| <50 years | 37 (14.6) | 32 (16.5) | 5 (8.3) | .111 |

| 50–65 years | 82 (32.3) | 63 (32.5) | 19 (31.7) | |

| >65 years | 135 (53.1) | 99 (51.0) | 36 (60.0) | |

| Barthel, median [Q1–Q3] | 100 [90−100] | 100 [95–100] | 90 [85–100] | <.001 |

| Barthel, patients, n (%) | ||||

| Independent (100) | 150 (59.1) | 127 (65.5) | 23 (38.4) | <.001 |

| With slight dependency (90−95) | 59 (23.2) | 42 (21.6) | 17 (28.3) | |

| With moderate dependency (60−85) | 37 (14.6) | 22 (11.3) | 15 (25.0) | |

| With serious dependency (20−55) | 7 (2.8) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (8.3) | |

| With total dependency (0−15) | 1 (.4) | 1 (.5) | 0 (.0) | |

| Employment situation, n (%) | ||||

| Student | 3 (1.2) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.7) | .001 |

| Full-time employment | 44 (17.3) | 44 (22.7) | 0 (.0) | |

| Part-time employment | 6 (2.3) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (5.0) | |

| Unemployed/state aid | 19 (7.5) | 13 (6.7) | 6 (10.0) | |

| Retired/pensioner | 156 (62.2) | 115 (59.3) | 43 (71.8) | |

| Sick leave | 5 (2.0) | 4 (2.1) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Others | 19 (7.4) | 13 (6.7) | 6 (10.0) | |

| BMI, n (%) | ||||

| Thin (<20) | 13 (5.1) | 9 (4.6) | 4 (6.7) | .943 |

| Normal (20–24) | 81 (31.9) | 60 (30.9) | 21 (35.0) | |

| Overweight (25–29) | 89 (35.0) | 74 (38.1) | 15 (25.0) | |

| Obesity (30–39) | 67 (26.4) | 48 (24.7) | 19 (31.7) | |

| Morbid obesity (>39) | 4 (1.6) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Charlson, points, median [Q1–Q3] | 4 [3–6] | 4 [2–6] | 4.5 [4–7] | .015 |

| SAPS III, points, median [Q1–Q3] | 62 [51–71] | 59 [50–70] | 67 [57–75] | .013 |

| SOFA, points, median [Q1–Q3] | 4 [3–6] | 3 [2.5–5] | 5 [3–7] | <.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation, | ||||

| Patients, n (%) | 174 (68.5) | 125 (64.4) | 49 (81.7) | .012 |

| Days, median [Q1–Q3] | 3 [0–8] | 3 [0–8] | 5 [1–13] | |

| Active mobility in ICU, | ||||

| Patients, n (%) | 95 (37.4) | 78 (40.7) | 17 (28.3) | .097 |

| Days, median [Q1–Q3] | 0 [0–2] | 0 [0–2] | 0 [0–2] | |

| Muscle weakness, patients, n (%) | 106 (41.7) | 79 (40.7) | 27 (45.0) | .557 |

| Pain, NS/ESCID scores, n (%) | ||||

| No pain (0−3) | 3989 (91.5) | 3047 (91.3) | 942 (92.4) | .232 |

| Pain (4−10) | 369 (8.5) | 292 (8.7) | 77 (7.6) | |

| RASS, scores, n (%) | ||||

| Agitation (>0) | 563 (12.4) | 404 (11.7) | 159 (14.3) | <.001 |

| Cooperative and calm (0 or −1) | 2293 (50.4) | 1825 (53.0) | 468 (42.2) | |

| Sedation (from −2 to −5) | 1697 (37.2) | 1215 (35.3) | 482 (43.5) | |

| Delirium, patients, n (%) | 40 (15.7) | 32 (16.5) | 8 (13.3) | .557 |

| Re-admissiona, patients, n (%) | ||||

| Before 3 months | 62 (35.6) | 55 (36.2) | 7 (31.8) | .814 |

| Before 6 months | 24 (15) | 22 (15.8) | 2 (9.5) | .743 |

| Before 9 months | 25 (17.5) | 21 (17.2) | 4 (19.0) | .764 |

| Before 12 months | 17 (13.9) | 14 (13.5) | 3 (16.7) | .716 |

| Stay, days, median [Q1–Q3] | ||||

| In ICU | 7 [4–14] | 7 [4–13] | 8 [5–14] | .391 |

| In hospital | 21 [13–36] | 21 [13–37] | 20 [12–33] | .648 |

| Death, patients, n (%) | ||||

| In ICU | 29 (11.4) | 16 (8.2) | 13 (21.7) | .004 |

| In hospital | 50 (19.7) | 25 (12.9) | 25 (41.7) | <.001 |

BMI: body mass index; CFS-Es: Clinical Frailty Scale-España; ESCID, Escala de Conductas Indicadoras de Dolor; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; NS: numerical scale; RASS: Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale; SAPS: Simplified Acute Physiologic Score; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

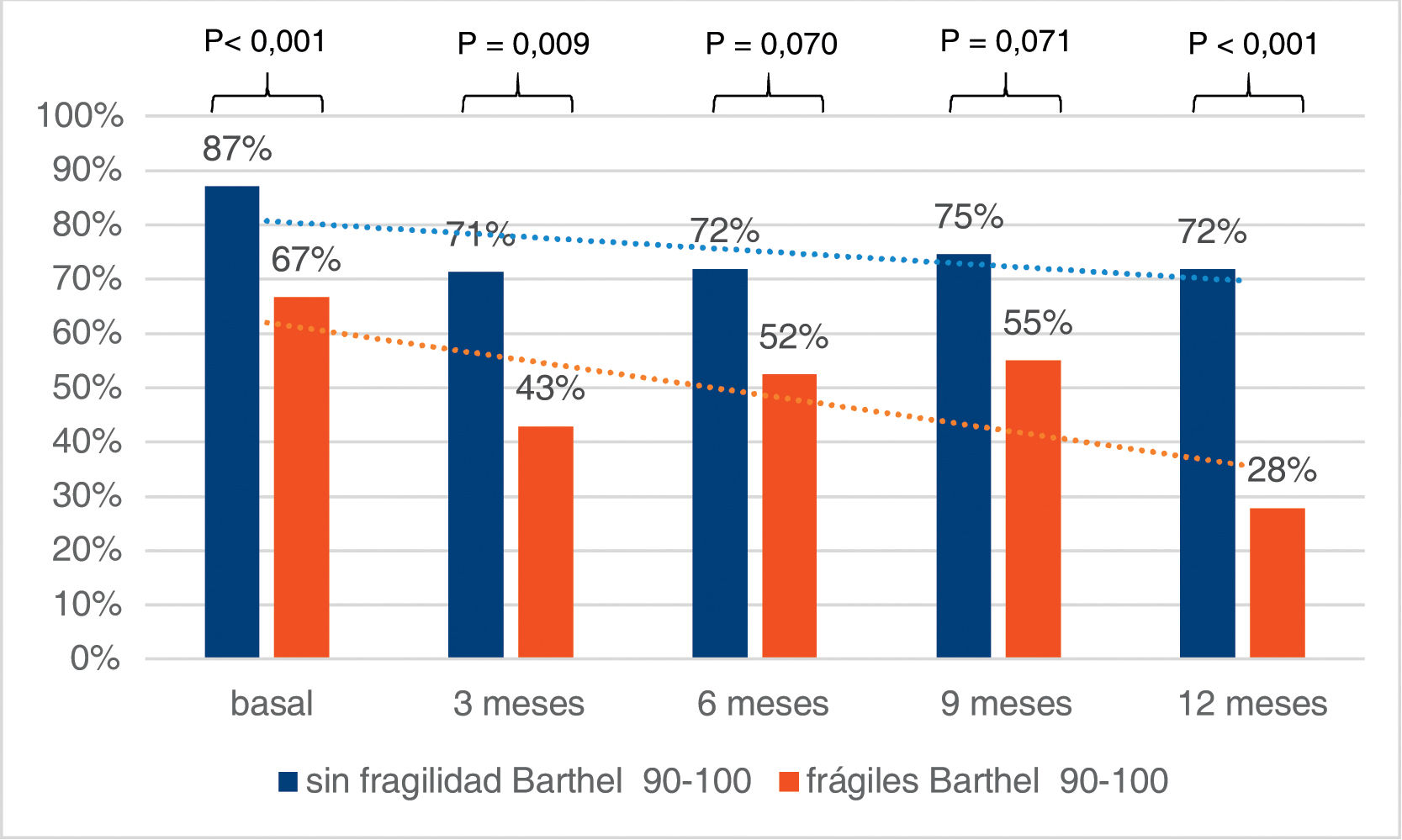

Of the 254, about 174 at 3 months, about 160 at 6 months, about 143 at 9 months and about 122 at 12 months. Of the 194 non-frail patients on admission, over 150 at 3 months, over 139 at 6 months, over 121 at 9 months and over 103 at 12 months. Of the 60 frail at admission, over 21 at 3 and 6 months, over 20 at 9 months and over 18 at 12 months.

The majority of patients [n (%): 174 (68.5)] had invasive mechanical ventilation, only 95 (37.4%) were actively mobilized (IMS-Es ≥4) during their ICU stay, 106 (41%) developed muscle weakness (MRS-SS <48) and 40 (15.7%) developed delirium at some point during ICU admission. Patients had no pain in 3989 (91.5%) measurements and in 2293 (49%) they were calm and cooperative (Table 1).

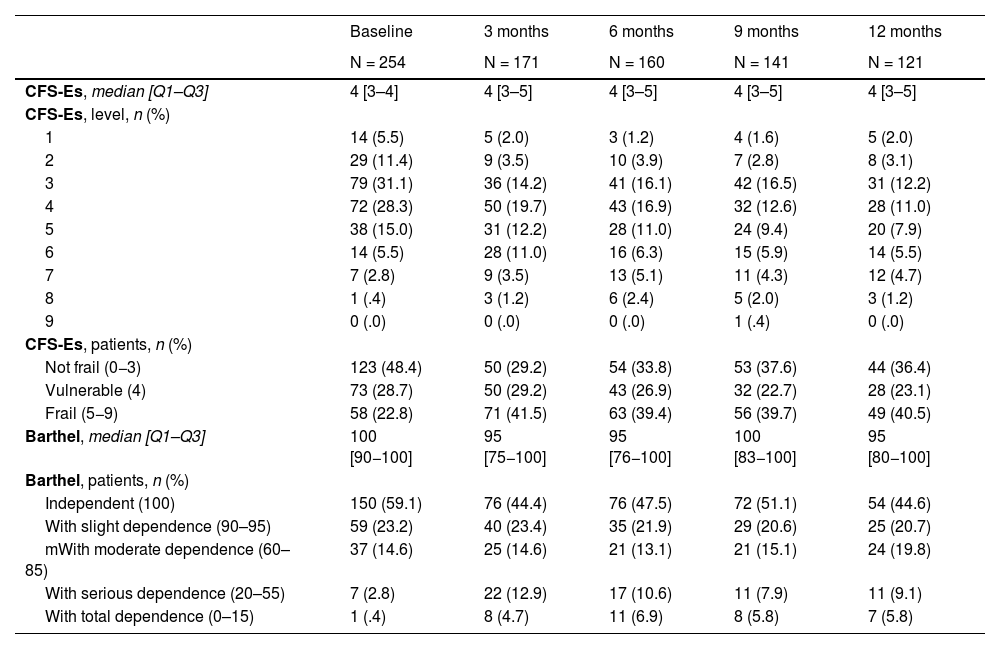

Regarding the evolution of frailty and dependence of patients after hospital discharge, we were able to observe an increase in frail patients (CFS-Es 5–9) between baseline and 3 months after hospital discharge [n (%): 60 (23) vs. 71 (41.5); p < .001], remaining at similar levels until one year after discharge. In the dependency, we also observed an increase in patients with Barthel <90, from the situation prior to admission vs. 3 months after hospital discharge [n (%): 45 (17.7) vs. 55 (32.2); p < .001] and in subsequent assessments (Table 2).

Evolution of dependence frailty.

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 254 | N = 171 | N = 160 | N = 141 | N = 121 | |

| CFS-Es, median [Q1–Q3] | 4 [3–4] | 4 [3–5] | 4 [3–5] | 4 [3–5] | 4 [3–5] |

| CFS-Es, level, n (%) | |||||

| 1 | 14 (5.5) | 5 (2.0) | 3 (1.2) | 4 (1.6) | 5 (2.0) |

| 2 | 29 (11.4) | 9 (3.5) | 10 (3.9) | 7 (2.8) | 8 (3.1) |

| 3 | 79 (31.1) | 36 (14.2) | 41 (16.1) | 42 (16.5) | 31 (12.2) |

| 4 | 72 (28.3) | 50 (19.7) | 43 (16.9) | 32 (12.6) | 28 (11.0) |

| 5 | 38 (15.0) | 31 (12.2) | 28 (11.0) | 24 (9.4) | 20 (7.9) |

| 6 | 14 (5.5) | 28 (11.0) | 16 (6.3) | 15 (5.9) | 14 (5.5) |

| 7 | 7 (2.8) | 9 (3.5) | 13 (5.1) | 11 (4.3) | 12 (4.7) |

| 8 | 1 (.4) | 3 (1.2) | 6 (2.4) | 5 (2.0) | 3 (1.2) |

| 9 | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 1 (.4) | 0 (.0) |

| CFS-Es, patients, n (%) | |||||

| Not frail (0−3) | 123 (48.4) | 50 (29.2) | 54 (33.8) | 53 (37.6) | 44 (36.4) |

| Vulnerable (4) | 73 (28.7) | 50 (29.2) | 43 (26.9) | 32 (22.7) | 28 (23.1) |

| Frail (5−9) | 58 (22.8) | 71 (41.5) | 63 (39.4) | 56 (39.7) | 49 (40.5) |

| Barthel, median [Q1–Q3] | 100 [90−100] | 95 [75−100] | 95 [76−100] | 100 [83−100] | 95 [80−100] |

| Barthel, patients, n (%) | |||||

| Independent (100) | 150 (59.1) | 76 (44.4) | 76 (47.5) | 72 (51.1) | 54 (44.6) |

| With slight dependence (90–95) | 59 (23.2) | 40 (23.4) | 35 (21.9) | 29 (20.6) | 25 (20.7) |

| mWith moderate dependence (60–85) | 37 (14.6) | 25 (14.6) | 21 (13.1) | 21 (15.1) | 24 (19.8) |

| With serious dependence (20–55) | 7 (2.8) | 22 (12.9) | 17 (10.6) | 11 (7.9) | 11 (9.1) |

| With total dependence (0–15) | 1 (.4) | 8 (4.7) | 11 (6.9) | 8 (5.8) | 7 (5.8) |

CFS-Es: Clinical Frailty Scale-España.

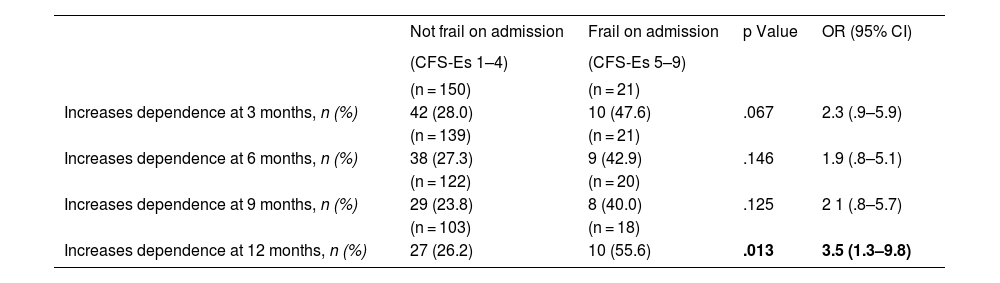

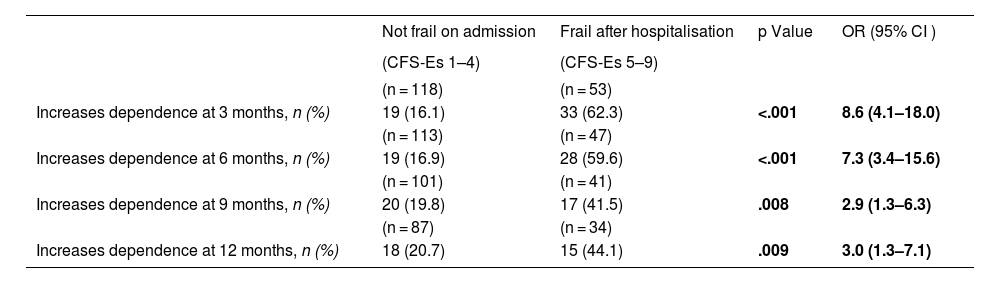

Upon admission we found a higher percentage of independent patients (Barthel 90–100) among the non-frail (CFS-Es 1–4) vs. the frail (CFS-Es 5–9) [87% vs. 67%; p < .001] (Fig. 2). Among the survivors after hospital discharge, there were fewer independent patients without frailty, but the percentage of non-frail independent patients was always higher than that of independent frail patients (Fig. 2). The increase in frail patient dependency upon admission, was always higher than those who were not frail before admission. This difference in increase was significant 12 months after discharge [OR (95% CI) = 3.5 (1.3–9.8); p = .013] (Table 3). Furthermore, with respect to patients who were not frail at admission, but with frailty after hospital discharge, significant increases in dependency were observed in all follow-up sections (Table 4).

Increase of dependence according to baseline frailty.

| Not frail on admission | Frail on admission | p Value | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (CFS-Es 1–4) | (CFS-Es 5–9) | |||

| (n = 150) | (n = 21) | |||

| Increases dependence at 3 months, n (%) | 42 (28.0) | 10 (47.6) | .067 | 2.3 (.9–5.9) |

| (n = 139) | (n = 21) | |||

| Increases dependence at 6 months, n (%) | 38 (27.3) | 9 (42.9) | .146 | 1.9 (.8–5.1) |

| (n = 122) | (n = 20) | |||

| Increases dependence at 9 months, n (%) | 29 (23.8) | 8 (40.0) | .125 | 2 1 (.8–5.7) |

| (n = 103) | (n = 18) | |||

| Increases dependence at 12 months, n (%) | 27 (26.2) | 10 (55.6) | .013 | 3.5 (1.3–9.8) |

CFS-Es: Clinical Frailty Scale-España; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Increase in dependence, in patients not frail prior to admission, according to frailty on hospital discharge.

| Not frail on admission | Frail after hospitalisation | p Value | OR (95% CI ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (CFS-Es 1–4) | (CFS-Es 5–9) | |||

| (n = 118) | (n = 53) | |||

| Increases dependence at 3 months, n (%) | 19 (16.1) | 33 (62.3) | <.001 | 8.6 (4.1–18.0) |

| (n = 113) | (n = 47) | |||

| Increases dependence at 6 months, n (%) | 19 (16.9) | 28 (59.6) | <.001 | 7.3 (3.4–15.6) |

| (n = 101) | (n = 41) | |||

| Increases dependence at 9 months, n (%) | 20 (19.8) | 17 (41.5) | .008 | 2.9 (1.3–6.3) |

| (n = 87) | (n = 34) | |||

| Increases dependence at 12 months, n (%) | 18 (20.7) | 15 (44.1) | .009 | 3.0 (1.3–7.1) |

CFS-Es: Clinical Frailty Scale-España; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

In the multivariate analysis, adjusted for age, sex, days of stay in the ICU and in the hospital, weakness acquired in the ICU and readmissions to an acute care hospital, it was observed that patients who change their frailty status (non-frail to frail) ) after admission, are 2.8 times (OR; 95% CI: 1.03–7.58; p = .043) more likely to increase dependency (Barthel 90–100 to <90 or Barthel <90–60 to <60) at 3 months after discharge and 3.5 times (OR; 95% CI: 1.18–10.30; p = .024) more likely to increase dependency at 12 months after discharge. Furthermore, for each additional CFS-Es point upon admission, the possibility of increasing dependency in the 12 months following discharge is multiplied by 1.6 (OR; 95% CI: 1.01–2.23; p = .016).

DiscussionIn our study, the Clinical Frailty Scale-España proved to have good predictive validity for increased dependency after admission to the ICU. Frail patients upon admission are more likely to be more dependent upon discharge from the hospital, even up to 12 months after it. Furthermore, patients who are not frail before admission, but are frail after hospital discharge, see their baseline dependency increase.

Frailty and its relationship with the increase in dependency or disability after admission to the ICU have been studied by several authors. This association has been analysed in elderly patients26,27 or those over 50 years of age,6,28 but it has also been reported in patients under 50 years of age.29

Ferrante et al.,26,27 in their studies with patients over 70 years of age, report an increase in disability at hospital discharge in frail patients (measured with the Frail Index) who have been admitted to the ICU. Bagshaw et al.6,28 also report how ICU admission of frail patients (CFS > 4) aged 50 years or older, independent before admission, are more likely than non-frail patients to become functionally dependent after admission to the ICU. Brummel et al.29 evaluate disability at discharge in ICU patients over 18 years of age, and report that increased frailty (CFS > 4) is associated with a greater probability of disability in instrumental activities, although not in basic activities of daily living. This increase in disability was not affected by age.

Being able to have a scale that can predict, in part, the dependency or disability of patients upon discharge from the hospital, after an ICU admission, can guide us towards specific care planning for the most fragile patients, or to identify what the risk factors are. They can be modifiable during the stay in the ICU, to prevent this dependency. For example, an algorithm published to promote early mobilization in the ICU already considered priority patients for mobilisation to be those with moderate dependency (Barthel between 60 and 90) and frailty (according to the FRAIL frailty scale [FRAIL > 3]).30

Outside of ICU care, it would be interesting if, for patients scheduled for complex surgeries that may require admission to the ICU, primary care would enhance physical conditioning in the previous weeks or months,31 maintain conditioning during hospital admission and continue functional recovery care in the appropriate area (primary care or in a specialised centre) after hospital discharge.32

There is an important limitation in this manuscript, the sample size, which has not allowed us to study the possible differences in the increase in dependency according to the different age strata, the sex of the patients or other characteristics present at the time of admission to the ICU.

ConclusionsThe Clinical Frailty Scale-España has been shown to be a scale with the ability to predict an increase in dependency after hospital discharge, in patients admitted to the ICU.

Funding.The present work was supported by the Spanish Health Research Fund of the Carlos III Health Institute, Ministry of of science and innovations, ISCIII-FIS grant PI20/01231.

Conflict of interestsS. Arias-Rivera and M. Raurell-Torredà are Editors of the journal Enfermería Intensiva, so, for the evaluation of this work, the procedure described in the guide for authors for these cases has been used. The rest of authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Getafe (Madrid): Raquel Jareño-Collado, Raquel Sánchez-Izquierdo, Eva I. Sánchez-Muñoz, Virginia López-López, Jesús Cidoncha-Moreno, Sonia López-Cuenca, Lorena Oteiza-López, Fernando Frutos-Vivar, María Nogueira-López, Marta Suero-Domínguez, M. Carmen Martín-Guzmán, Olga Rodríguez-Estévez, Juan Enrique Mahía-Cures. Centro de salud Getafe Norte, Getafe (Madrid): Pedro Vadillo-Obesso. Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo (Asturias): Julieta Alonso-Soto, Esther González-Alonso, Lara María Rodríguez-Villanueva, Montserrat Fernández-Menéndez, Roberto Riaño-Suárez, María González-Pisano, Adrián González-Fernández, Helena Fernández-Alonso, José Antonio Gonzalo-Guerra. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno-Infantil, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Canarias): Zaida Álamo-Rodríguez, Famara Díaz-Marrero, Benjamín Guedes-Santana, Aridane Méndez-Santana, José Rodríguez-Alemán, Lorea Ugalde-Jauregui. Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid (Madrid): Ángeles Ponce-Figuereo, Ana Muñoz-Martínez, Iñaki Erquicia-Peralt. Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat (Barcelona): Laia Martínez-Bosch, Jordi Torreblanca-Parra, Vicente Corral-Vélez.

Please cite this article as: Arias-Rivera S, Sánchez-Sánchez MM, Romero de-San-Pío E, Santana-Padilla YG, Juncos-Gozalo M, Via-Clavero G, et al. Validez predictiva de la escala de fragilidad Clinical Frailty Scale-España sobre el incremento de la dependencia tras el alta hospitalaria. Enferm Intensiva. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfi.2023.07.003