Pregnancy and postpartum are sensitive periods for mental health problems due to increased stressors and demands, and the prevalence of intentional self-harming behaviors such as suicidal behavior and ideation may increase. Changes in the provision of prenatal care services and utilization of health services and adverse living conditions during the COVID-19 epidemic may also trigger or exacerbate mental illnesses.

AimsTo investigate the prevalence of suicidal behavior and ideation encountered during pregnancy and postpartum period, its change in the COVID-19 pandemic, and the related factors.

MethodsA systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies was conducted. A search was conducted in April 2021 and updated in April 2023 on Web of Science, PubMed, PsycINFO, EBSCO, Turk Medline, Turkish Clinics, and ULAKBIM databases. Two authors independently conducted the search, selection of articles, data extraction, and quality assessment procedures, and an experienced researcher controlled all these steps. Joanna Briggs Institute's Critical Appraisal Checklists were used to assess the quality of the studies.

ResultsThe meta-analysis included 38 studies and the total sample size of the studies was 9 044 991. In this meta-analysis, the prevalence of suicidal behavior in women during pregnancy and postpartum periods was 5.1 % (95 % CI, 0.01–1.53), suicidal ideation 7.2 % (95 % CI, 0.03–0.18), suicide attampt 1 % (95 % CI, 0.00–0.07) and suicidal plan 7.8 % (95 % CI, 0.06–0.11). Rate of suicidal behavior, ideation/thought increased and attempts in the pandemic process (2.5% vs 19.7 %; 6.3% vs 11.3 %; 3.6% vs 1.4 %, respectively). Prevalences of suicidal behavior, ideation, attempts, and plan in the postpartum period was higher than during pregnancy (1.1% vs 23.4 %; 6.1% vs 9.2 %; 0.5% vs 0.7 %; 7.5% vs 8.8 %, respectively). This systematic review showed that suicidal behavior increases due to many factors such as individual and obstetric characteristics, economic and socio-cultural factors, domestic violence, and a history of physical and mental illness.

ConclusionThis study revealed that suicidal behavior in the perinatal period is quite common, especially in high-risk groups, and it increases even more during the pandemic period. Being aware of the sensitivity of the perinatal period in terms of suicidal behavior, healthcare professionals can improve mother-baby health by identifying high-risk groups and providing preventive and health-promoting services.

Registration number: CRD42021246334.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines suicidal behavior as an important global public health problem.1 Suicidal behaviour is descripted as a diversity of behaviour that includes thinking about suicide (or suicidal ideation), planning suicide, attempting suicide and committing an act of suicide.2,3 WHO reports that approximately 703 000 people worldwide engage in suicidal behavior annually, and many more have serious suicidal thoughts.4 According to the national statistics of Turkey on the cause of deaths, 780 women in 2019 and 863 women in 2020 and 920 women in 2021 died by suicide and intentional self-harm.5 Pregnancy and postpartum periods are a sensitive period for people with behavioral health problems due to increased stressors and demands, and the prevalence of suicidal ideation and intentional self-harm behaviors may increase during these periods.2,6–8 On the other hand, changes in the delivery of health care services and the behavior of benefiting from health services during the COVID-19 pandemic may increase negative living conditions and experiences such as symptoms of mental illness.9,10 In this context, further revealing the relationships between suicidal behaviors and high risk factors in the perinatal care service process may be beneficial for healthcare providers.

It is also known that pregnancy and the postpartum period cause affect changes in women with the interaction of biological and environmental factors and increase susceptibility to mental illnesses.11 As a result of this sensitive period, some women may be driven to suicide.12,13 Suicidal behavior is very important because of the burden on the life of the woman, the growth and development of the baby, the function of the family, and society as a whole. In addition, suicidal behavior that occurs during these periods has critical consequences, such as miscarriage, abortion, premature birth, increased hospitalization rates, intrauterine death, stillbirth, bleeding, and maternal death.12,14,15

Although the postpartum period is generally defined as the first six weeks (42 days) after birth, it is reported that late maternal morbidity and mortality continue up to one year postpartum. In this context, studies have shown that postpartum mental problems spread throughout the first year after birth.3,6,7,10,12

Studies have shown that the incidence of suicidal behavior during pregnancy is quite common. Some studies have shown that the prevalence of suicidal ideation during pregnancy ranges between 2.73 % and 20 %3,16 and that the prevalence of suicide attempts varies between 1.7 % and 12.6 %.17–19 Some studies conducted in South Africa have shown that suicidal ideation varies between 3.3 % and 27.5 % and suicide attempts between 1.8 % and 20.4 %.20,21 Also, in a systematic review in which the results of 57 studies were reported, it was stated that the prevalence of suicide during pregnancy ranged from 3 % to 33 %.16 In another meta-analysis, it was reported that the prevalence of any of the suicidal behaviors was 11 %, the prevalence of suicidal ideation was 12 %, and the prevalence of suicide attempt was 4 % in the postpartum period.6 Chin et al.,22 reported that prevalence of suicidal ideation in the perinatal period ranges from 2 to 5 % among women seeking obstetrical care. Another study reported that perinatal suicide accounts for 5 % to 44 % of all maternal deaths in high-income countries.12

There are many individual and cultural factors that affect suicide attempts during pregnancy and the postpartum period. These include unemployment, low socioeconomic status,21,23,24 single-parent status and low education level,16,19,25 unwanted and unplanned pregnancy,26,27 suicidal ideation and attempts before pregnancy, family history of suicide,16,22,28 comorbid mental disorders and chronic physical illnesses,24,25 adolescent pregnancy, extramarital pregnancy, and emotional and sexual abuse.25 In addition, poor social support,24,26 partner violence,16,19,22,23,25 and use of psychoactive substances18,22 are stated as important factors contributing to suicidal ideation and attempts in women with pregnancy. In addition to these, the COVID-19 pandemic has recently come to the fore as a risk factor for mental disorders.29

Pregnant and puerperal women may be more sensitive than the general population due to the increased anxiety about their babies and their need for continuous care and social support during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this may trigger suicidal behaviors.7,30 In a study by Yang et al., it was reported that self-harm/suicidal ideation of pregnant women was slightly higher than the prevalence rate reported before the COVID-19 pandemic.29

There are some recent systematic review studies on the prevalence of suicidal behavior and risk factors in the perinatal period in the literature.3,6,7,11,12,23 Only one of these studies had a meta-analysis on the prevalence of suidal ideation in the postpartum period.6 However, there was no meta-analysis study in which the results of the studies conducted before and after the COVID-19 pandemic were compared and the effects of the pandemic process were revealed, and it was decided to conduct this study. In addition, we aimed to reveal more recent data in this study. It is expected that the information obtained will contribute to the presentation of health services related to the protection and development of mother-infant and family health.

Aim and research questionsIn this systematic review, we aimed to determine the incidence of suicidal behavior and ideation encountered during pregnancy and the postpartum period, its variation in the COVID-19 pandemic, and the factors related to it based on the results of previous studies. Accordingly, we sought answers to the following questions: 1) What is the incidence of suicidal behaviors and ideation encountered during pregnancy and postpartum period? 2) What are the factors affecting the suicidal behaviors and ideation encountered in these periods? 3) Does the pandemic have an effect on the frequency of suicidal behavior and ideation encountered in these periods?

MethodsStudy designA systematic review and meta-analysis study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)31 and Conducting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies of Etiology (COSMOS-E)32 guidelines. The review protocol was registered at PROSPERO as CRD42021246334.

Inclusion criteria for the studiesIn this systematic review, studies were selected according to the following inclusion criteria (PEOS): Study group (P): Pregnant or women in the postpartum period. Exposure (E): Suicidal behavior and COVID-19 pandemic. Outcomes (O): Presence of suicidal behavior, frequency of suicidal behavior (suicidal behavior, suidal ideation/thought, suicide attempt, suicidal plan, as reported in studies) in the pre-and post-COVID-19 pandemic periods, and factors associated with suicidal behavior. Study design (S): Cross-sectional and cohort studies published in the Turkish and English languages in the 2017 and later periods.

The exclusion criteria of the study consisted of studies whose methods were unclear, whose full text could not be reached, and which were designed as case-control, experimental and quasi-experimental, and systematic or traditional reviews.

Data sources and search strategiesThe searches for this systematic review were conducted in April 2021 and updated between 15 and 20 April 2023 on Web of Science, PubMed (including MEDLINE), PsycINFO (All via Ovid SP), EBSCO, Turk Medline, Turkish Clinics, and ULAKBIM-Ekual (Dergipark) databases by using the keywords “(suicide OR suicidal behavior OR suicide attempt OR suidal ideation OR suidal ideation OR suicidal plan) AND (pregnancy OR postpartum)”. The references lists of included studies and previous review studies on the topic were examined to obtain additional studies.

Determination and selection of studiesStudies addressing the frequency of suicidal behavior and related factors during pregnancy and postpartum were selected for this systematic review. The determination and selection procedures of studies were conducted independently by the second and third researchers in accordance with the established inclusion criteria. After the repetitive ones were removed, studies were selected according to title, abstract, and full text, respectively.

Extraction of the study dataThe data extraction tool developed by the researchers was used to obtain the research data. The tool was utilized to obtain data about the studies included in the systematic review, such as author and publication year, country of the study, study design, sample size, data collection tools, year of data collection, mean age of the participants, number of suicidal behavior and/or suicide attempt cases, date of data collection, and related factors.

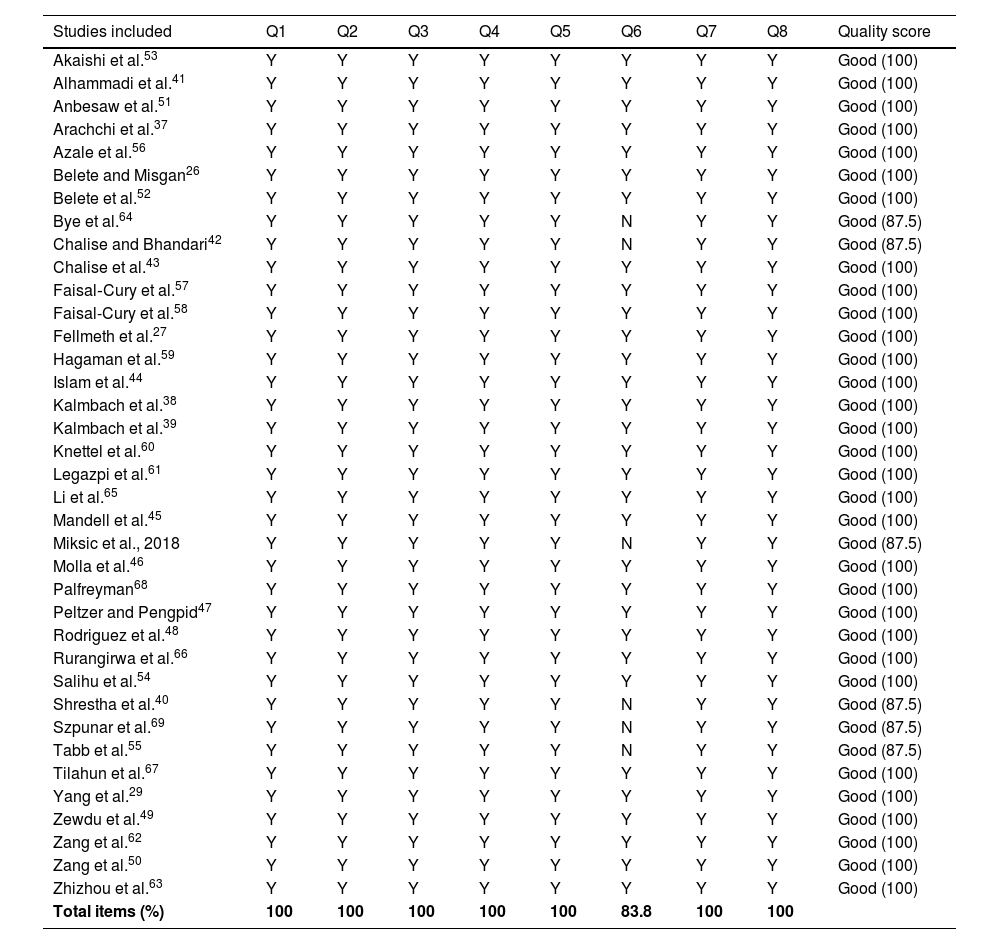

Assessment of the methodological quality of the studiesThe JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies published by the Joanna Briggs Institute was used to make the methodological quality assessment of the articles included in this systematic review.33 In this study, studies in the cohort design included in the meta-analysis were also evaluated with this tool, since they were in the form of follow-ups on pregnancy and postpartum processes, and the studies were not designed according to case and control groups. This process was carried out independently by the second and third researchers, and the resulting assessments, which were converted into a single text, were checked by the first researcher. A checklist, which consisted of eight questions, was used in the process, and the answers to the questions were “yes, no, uncertain, and not applicable”. The level of methodological quality was determined as follows: fair quality if less than 50 % of the items were rated as ‘‘yes,’’ moderate quality if between 51 % and 80 % of the items were rated as ‘‘yes,’’ and good quality if more than 80 % of the items were rated as ‘‘yes’’. No studies were excluded based on methodological quality assessment.

Synthesis of the dataThe quantitative data were synthesized by doing a meta-analysis. A 95 % confidence interval (CI) and estimated ratios were calculated for each outcome variable. Meta-regression and subgroup analyzes were performed to determine the effects of the pandemic process, perinatal periods, and high-risk status of the study group on suicidal behavior and types in this meta-analysis. In addition, the narrative synthesis method was used for the synthesis of data on the factors associated with suicidal behavior reported in studies.

Meta-analysis and meta-regression were conducted by using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V4 software.34 Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the Cochran Q test and Higgins I², and an I² of greater than 50 % indicated significant heterogeneity. I2 is 0–40 % indicated might not be important, I2 is 30–60 % represented moderate heterogeneity, I2 is 50 %–90 % represented substantial heterogeneity, I2 is 75–100 % indicated considerable heterogeneity.35 Random effect results were obtained if I² was more than 50 % and fix effect if it was less. All tests were calculated in two ways, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

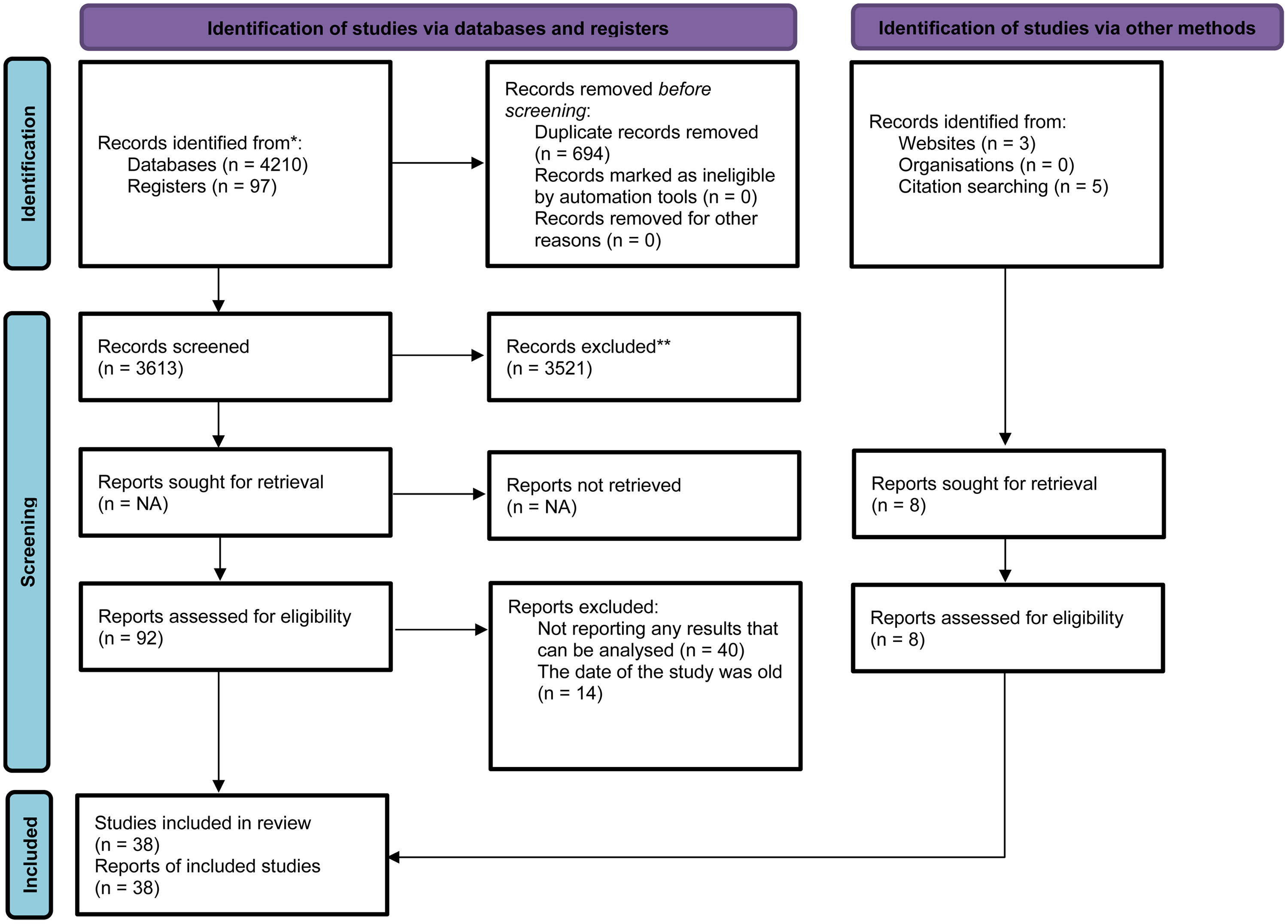

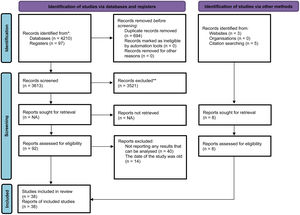

ResultsSearch resultsA total of 4307 articles were reached at the beginning of the search process. As a result of the removal of repetitive records and then the analysis conducted according to titles and abstracts, 92 articles were selected for full-text review. A total of 38 studies were determined for meta-analysis after the examination of the studies according to the inclusion criteria and the addition of extra studies (Fig. 1). A study conducted during the pandemic and published as a letter to the editor was included in this review because it contains comprehensive data that can be taken for meta-analysis regarding pregnancy and postpartum periods.36

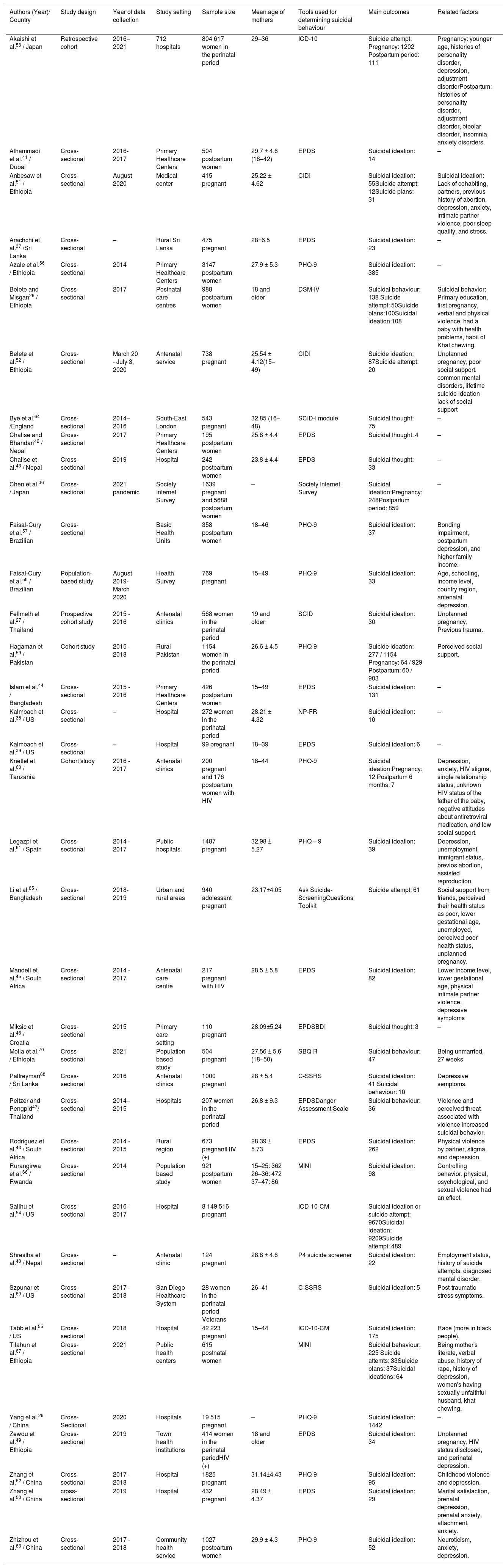

Characteristics of the studies and participantsStudies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted between 2014 and 2021 and published between 2017 and 2023. The time of data collection was not reported in four studies.37-40 The total sample size of the studies was 9 044 991. Thirty-four of the studies were cross-sectional and four were cohort designs. All of the studies had been published in English. They had been conducted in 17 different countries. In the studies, the age range and average age of women were reported in the range of 15–50 years (Table 1).

Characteristics, main findings, and related factors of cross-sectional studies on suicide attempts included in the systematic review.

| Authors (Year)/ Country | Study design | Year of data collection | Study setting | Sample size | Mean age of mothers | Tools used for determining suicidal behaviour | Main outcomes | Related factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akaishi et al.53 / Japan | Retrospective cohort | 2016–2021 | 712 hospitals | 804 617 women in the perinatal period | 29–36 | ICD-10 | Suicide attempt: Pregnancy: 1202 Postpartum period: 111 | Pregnancy: younger age, histories of personality disorder, depression, adjustment disorderPostpartum: histories of personality disorder, adjustment disorder, bipolar disorder, insomnia, anxiety disorders. |

| Alhammadi et al.41 / Dubai | Cross-sectional | 2016- 2017 | Primary Healthcare Centers | 504 postpartum women | 29.7 ± 4.6 (18–42) | EPDS | Suicidal ideation: 14 | – |

| Anbesaw et al.51 / Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | August 2020 | Medical center | 415 pregnant | 25.22 ± 4.62 | CIDI | Suicidal ideation: 55Suicide attempt: 12Suicide plans: 31 | Suicidal ideation: Lack of cohabiting, partners, previous history of abortion, depression, anxiety, intimate partner violence, poor sleep quality, and stress. |

| Arachchi et al.37 /Sri Lanka | Cross- sectional | – | Rural Sri Lanka | 475 pregnant | 28±6.5 | EPDS | Suicidal ideation: 23 | – |

| Azale et al.56 / Ethiopia | Cross- sectional | 2014 | Primary Healthcare Centers | 3147 postpartum women | 27.9 ± 5.3 | PHQ-9 | Suicidal ideation: 385 | – |

| Belete and Misgan26 / Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 2017 | Postnatal care centres | 988 postpartum women | 18 and older | DSM-IV | Suicidal behaviour: 138 Suicide attempt: 50Suicide plans:100Suicidal ideation:108 | Suicidal behavior: Primary education, first pregnancy, verbal and physical violence, had a baby with health problems, habit of Khat chewing. |

| Belete et al.52 / Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | March 20 - July 3, 2020 | Antenatal service | 738 pregnant | 25.54 ± 4.12(15–49) | CIDI | Suicide ideation: 87Suicide attempt: 20 | Unplanned pregnancy, poor social support, common mental disorders, lifetime suicide ideation lack of social support |

| Bye et al.64 /England | Cross-sectional | 2014–2016 | South-East London | 543 pregnant | 32.85 (16–48) | SCID-I module | Suicidal thought: 75 | – |

| Chalise and Bhandari42 / Nepal | Cross-sectional | 2017 | Primary Healthcare Centers | 195 postpartum women | 25.8 ± 4.4 | EPDS | Suicidal thought: 4 | – |

| Chalise et al.43 / Nepal | Cross-sectional | 2019 | Hospital | 242 postpartum women | 23.8 ± 4.4 | EPDS | Suicidal thought: 33 | – |

| Chen et al.36 / Japan | Cross-sectional | 2021 pandemic | Society Internet Survey | 1639 pregnant and 5688 postpartum women | – | Society Internet Survey | Suicidal ideation:Pregnancy: 248Postpartum period: 859 | – |

| Faisal‑Cury et al.57 / Brazilian | Cross-sectional | Basic Health Units | 358 postpartum women | 18–46 | PHQ-9 | Suicidal ideation: 37 | Bonding impairment, postpartum depression, and higher family income. | |

| Faisal-Cury et al.58 / Brazilian | Population-based study | August 2019- March 2020 | Health Survey | 769 pregnant | 15–49 | PHQ-9 | Suicidal ideation: 33 | Age, schooling, income level, country region, antenatal depression. |

| Fellmeth et al.27 / Thailand | Prospective cohort study | 2015 - 2016 | Antenatal clinics | 568 women in the perinatal period | 19 and older | SCID | Suicidal ideation: 30 | Unplanned pregnancy, Previous trauma. |

| Hagaman et al.59 / Pakistan | Cohort study | 2015 - 2018 | Rural Pakistan | 1154 women in the perinatal period | 26.6 ± 4.5 | PHQ-9 | Suicide ideation: 277 / 1154 Pregnancy: 64 / 929 Postpartum: 60 / 903 | Perceived social support. |

| Islam et al.44 / Bangladesh | Cross-sectional | 2015 - 2016 | Primary Healthcare Centers | 426 postpartum women | 15–49 | EPDS | Suicidal ideation: 131 | – |

| Kalmbach et al.38 / US | Cross-sectional | – | Hospital | 272 women in the perinatal period | 28.21 ± 4.32 | NP-FR | Suicidal ideation: 10 | – |

| Kalmbach et al.39 / US | Cross-sectional | – | Hospital | 99 pregnant | 18–39 | EPDS | Suicidal ideation: 6 | – |

| Knettel et al.60 / Tanzania | Cohort study | 2016 - 2017 | Antenatal clinics | 200 pregnant and 176 postpartum women with HIV | 18–44 | PHQ-9 | Suicidal ideation:Pregnancy: 12 Postpartum 6 months: 7 | Depression, anxiety, HIV stigma, single relationship status, unknown HIV status of the father of the baby, negative attitudes about antiretroviral medication, and low social support. |

| Legazpi et al.61 / Spain | Cross-sectional | 2014 - 2017 | Public hospitals | 1487 pregnant | 32.98 ± 5.27 | PHQ – 9 | Suicidal ideation: 39 | Depression, unemployment, immigrant status, previos abortion, assisted reproduction. |

| Li et al.65 / Bangladesh | Cross-sectional | 2018- 2019 | Urban and rural areas | 940 adolessant pregnant | 23.17±4.05 | Ask Suicide-ScreeningQuestions Toolkit | Suicide attempt: 61 | Social support from friends, perceived their health status as poor, lower gestational age, unemployed, perceived poor health status, unplanned pregnancy. |

| Mandell et al.45 / South Africa | Cross-sectional | 2014 - 2017 | Antenatal care centre | 217 pregnant with HIV | 28.5 ± 5.8 | EPDS | Suicidal ideation: 82 | Lower income level, lower gestational age, physical intimate partner violence, depressive symptoms |

| Miksic et al.46 / Croatia | Cross-sectional | 2015 | Primary care setting | 110 pregnant | 28.09±5.24 | EPDSBDI | Suicidal thought: 3 | – |

| Molla et al.70 / Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 2021 | Population based study | 504 pregnant | 27.56 ± 5.6 (18–50) | SBQ-R | Suicidal behaviour: 47 | Being unmarried, 27 weeks |

| Palfreyman68 / Sri Lanka | Cross-sectional | 2016 | Antenatal clinics | 1000 pregnant | 28 ± 5.4 | C-SSRS | Suicidal ideation: 41 Suicidal behaviour: 10 | Depressive semptoms. |

| Peltzer and Pengpid47/ Thailand | Cross-sectional | 2014–2015 | Hospitals | 207 women in the perinatal period | 26.8 ± 9.3 | EPDSDanger Assessment Scale | Suicidal behaviour: 36 | Violence and perceived threat associated with violence increased suicidal behavior. |

| Rodriguez et al.48 / South Africa | Cross-sectional | 2014 - 2015 | Rural region | 673 pregnantHIV (+) | 28.39 ± 5.73 | EPDS | Suicidal ideation: 262 | Physical violence by partner, stigma, and depression. |

| Rurangirwa et al.66 / Rwanda | Cross-sectional | 2014 | Population based study | 921 postpartum women | 15–25: 362 26–36: 472 37–47: 86 | MINI | Suicidal ideation: 98 | Controlling behavior, physical, psychological, and sexual violence had an effect. |

| Salihu et al.54 / US | Cross-sectional | 2016–2017 | Hospital | 8 149 516 pregnant | ICD-10-CM | Suicidal ideation or suicide attempt: 9670Suicidal ideation: 9209Suicide attempt: 489 | ||

| Shrestha et al.40 / Nepal | Cross-sectional | – | Antenatal clinic | 124 pregnant | 28.8 ± 4.6 | P4 suicide screener | Suicidal ideation: 22 | Employment status, history of suicide attempts, diagnosed mental disorder. |

| Szpunar et al.69 / US | Cross-sectional | 2017 - 2018 | San Diego Healthcare System | 28 women in the perinatal period Veterans | 26–41 | C-SSRS | Suicidal ideation: 5 | Post-traumatic stress symptoms. |

| Tabb et al.55 / US | Cross-sectional | 2018 | Hospital | 42 223 pregnant | 15–44 | ICD-10-CM | Suicidal ideation: 175 | Race (more in black people). |

| Tilahun et al.67 / Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 2021 | Public health centers | 615 postnatal women | MINI | Suicidal behaviour: 225 Suicide attemts: 33Suicide plans: 37Suicidal ideations: 64 | Being mother's literate, verbal abuse, history of rape, history of depression, women's having sexually unfaithful husband, khat chewing. | |

| Yang et al.29 / China | Cross-Sectional | 2020 | Hospitals | 19 515 pregnant | – | PHQ-9 | Suicidal ideation: 1442 | – |

| Zewdu et al.49 / Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 2019 | Town health institutions | 414 women in the perinatal periodHIV (+) | 18 and older | EPDS | Suicidal ideation: 34 | Unplanned pregnancy, HIV status disclosed, and perinatal depression. |

| Zhang et al.62 / China | Cross-sectional | 2017 - 2018 | Hospital | 1825 pregnant | 31.14±4.43 | PHQ-9 | Suicidal ideation: 95 | Childhood violence and depression. |

| Zhang et al.50 / China | cross-sectional | 2019 | Hospital | 432 pregnant | 28.49 ± 4.37 | EPDS | Suicidal ideation: 29 | Marital satisfaction, prenatal depression, prenatal anxiety, attachment, anxiety. |

| Zhizhou et al.63 / China | Cross-sectional | 2017 - 2018 | Community health service | 1027 postpartum women | 29.9 ± 4.3 | PHQ-9 | Suicidal ideation: 52 | Neuroticism, anxiety, depression. |

EPDS: The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; NP-FR: Nocturnal perinatal-focused rumination; MINI: The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; C-SSRS: Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV; CIDI: Composite International Diagnostic Interview; ICD-10-CM: International Classifcation of Diseases, 9th Edition, Clinical Modifcation codes; SBQ-R: Suicidal behavior questionnaire; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnosis of DSM-IV Disorders.

The following scales were used in the studies to determine the suicidal behavior: Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) in 12 studies37,38,41–50; Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in two studies51,52; International Clasification of Diseases (ICD)−10 in three studies53–55; Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) in nine studies29,56–63; DSM-IV in one study26; SCID-I Module in two study27,64; Nocturnal perinatal-focused rumination (NP-FR) in one study38; Ask Suicide Screaning Questions Toolkit in one study65; Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) in one study46; Danger Assessment Scale in one study47; the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) in two study66,67; Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) in two study68,69; Society Internet Survey in one study36; Suicidal behavior questionnaire (SBQ-R) in one study70; P4 suicide screener in one study40 (Table 1).

Suicidal behavior was defined as “suicidal ideation” in 30 studies, “suicidal thoughts” in four studies, “suicidal attempts” in seven studies, “suicidal behavior” in six studies, three different forms of suicidal behavior (attempt, plan, and ideation) in three study, three different forms of suicidal behavior (ideation and attempt or behavior) in one study. Of the studies, 19 were performed during pregnancy, 10 during postpartum, and nine during pregnancy and postpartum periods. Five studies included in the meta-analysis in this dataset were carried out with groups with high risk (HIV cases in four studies and veterans in one of them).45,48,49,60,69

Quality assessment results of the studiesThe studies were found to have a good quality, with 8/8 (100 %) “Yes” responses in 31 studies and 7/8 (84.2 %) “Yes” responses in six studies. As a result, all of the studies reviewed met most items of the assessment tool and had a low risk of bias (Table 2). No quality assessment was made of a study that was a letter to the editor.36

Quality assessment of the studies included in the study.

| Studies included | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akaishi et al.53 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Alhammadi et al.41 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Anbesaw et al.51 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Arachchi et al.37 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Azale et al.56 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Belete and Misgan26 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Belete et al.52 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Bye et al.64 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Good (87.5) |

| Chalise and Bhandari42 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Good (87.5) |

| Chalise et al.43 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Faisal‑Cury et al.57 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Faisal-Cury et al.58 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Fellmeth et al.27 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Hagaman et al.59 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Islam et al.44 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Kalmbach et al.38 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Kalmbach et al.39 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Knettel et al.60 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Legazpi et al.61 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Li et al.65 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Mandell et al.45 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Miksic et al., 2018 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Good (87.5) |

| Molla et al.46 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Palfreyman68 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Peltzer and Pengpid47 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Rodriguez et al.48 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Rurangirwa et al.66 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Salihu et al.54 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Shrestha et al.40 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Good (87.5) |

| Szpunar et al.69 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Good (87.5) |

| Tabb et al.55 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Good (87.5) |

| Tilahun et al.67 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Yang et al.29 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Zewdu et al.49 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Zang et al.62 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Zang et al.50 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Zhizhou et al.63 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Good (100) |

| Total items (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 83.8 | 100 | 100 |

Q: question; Y: yes; N: no.

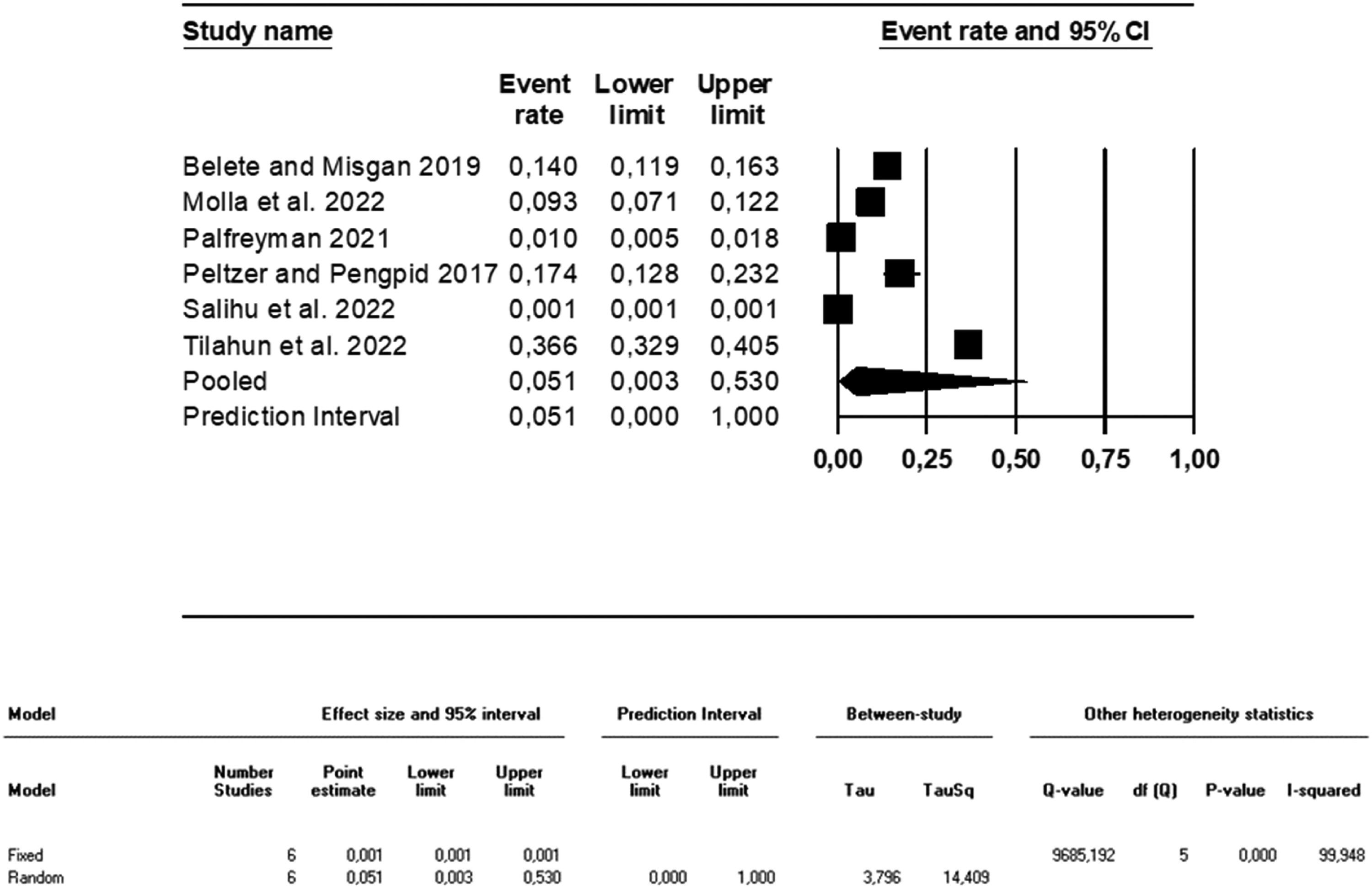

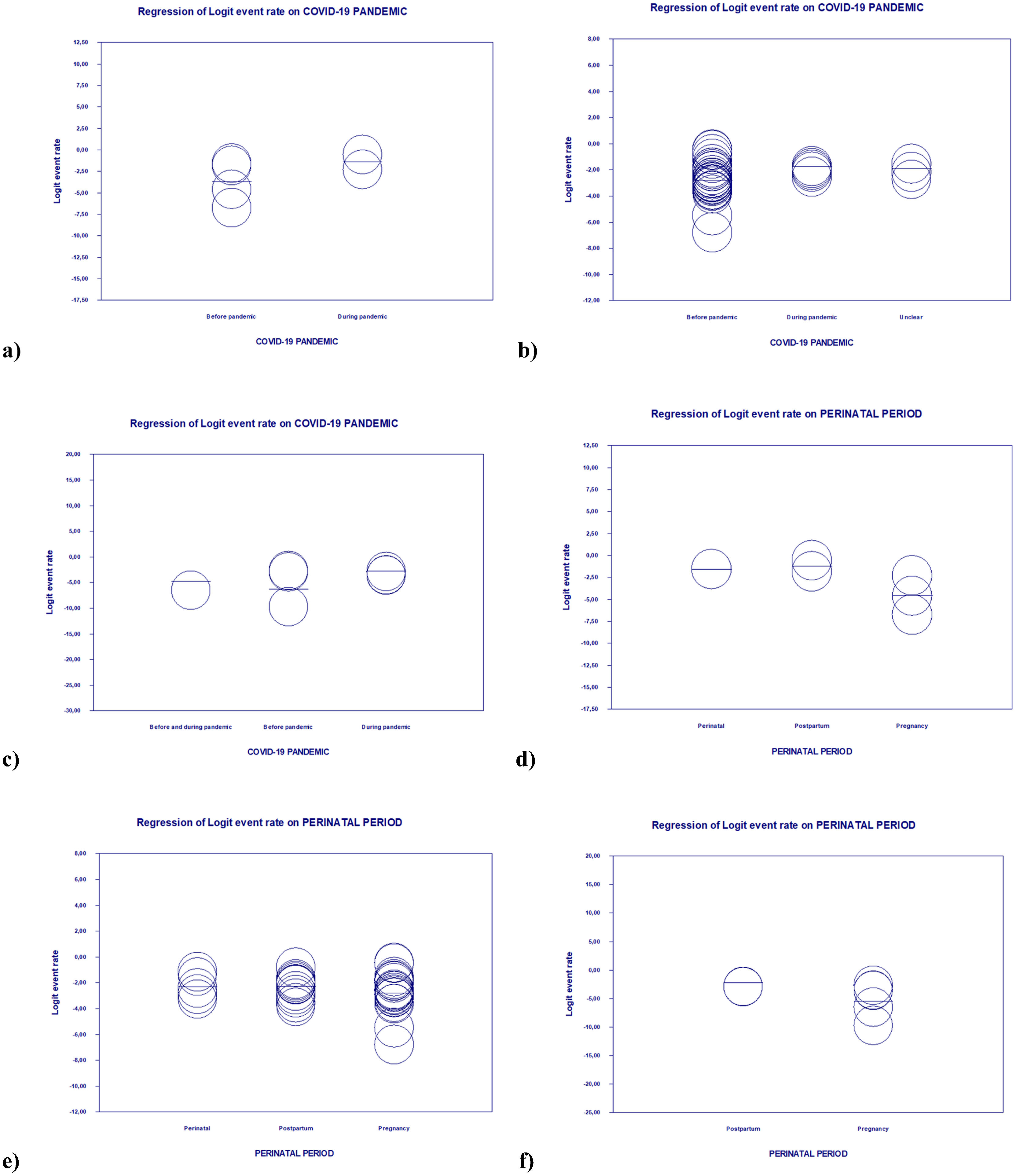

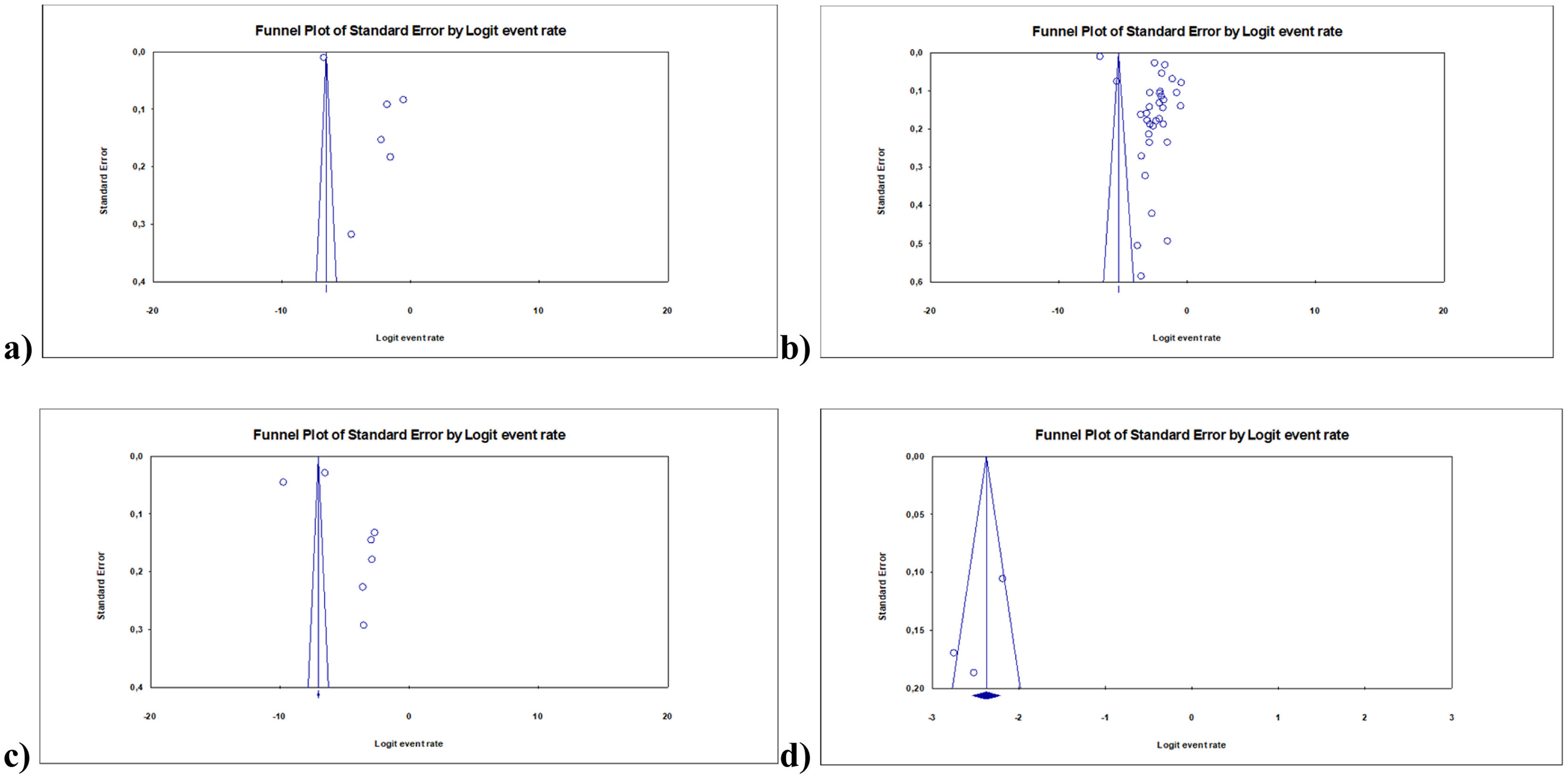

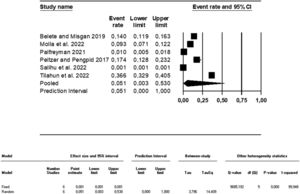

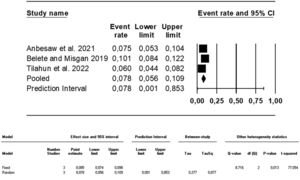

In six of the studies included in the systematic review, there was a finding of suicidal behavior during pregnancy and postpartum periods.26,47,54,67,68,70 Poled results of these studies, the prevalence of suicidal behavior was 5.1 % (95 % CI, 0.01–1.53; I2= 99.95; Fig. 2). While this rate was 2.5 % (95 % CI, 0.00–0.42; I2= 99.90) in the pre-pandemic period, it was 19.7 % (95 % CI, 0.04–0.57; I2= 98.98) in the pandemic period. This rate was 1.1 % during pregnancy (95 % CI, 0.00–0.23; I2= 99.78) and 23.4 % in the postpartum period (95 % CI, 0.33–0.41; I2= 99.04). However, meta-regression showed that there was no statistically significant effect of the pandemic period, having high risk and perinatal periods moderator variables on suicidal behavior (respectively, z = 0.83, p = 0.41; z= −0.39, p = 0.70; z= −1.25, p = 0.21; Fig. 3a and d).

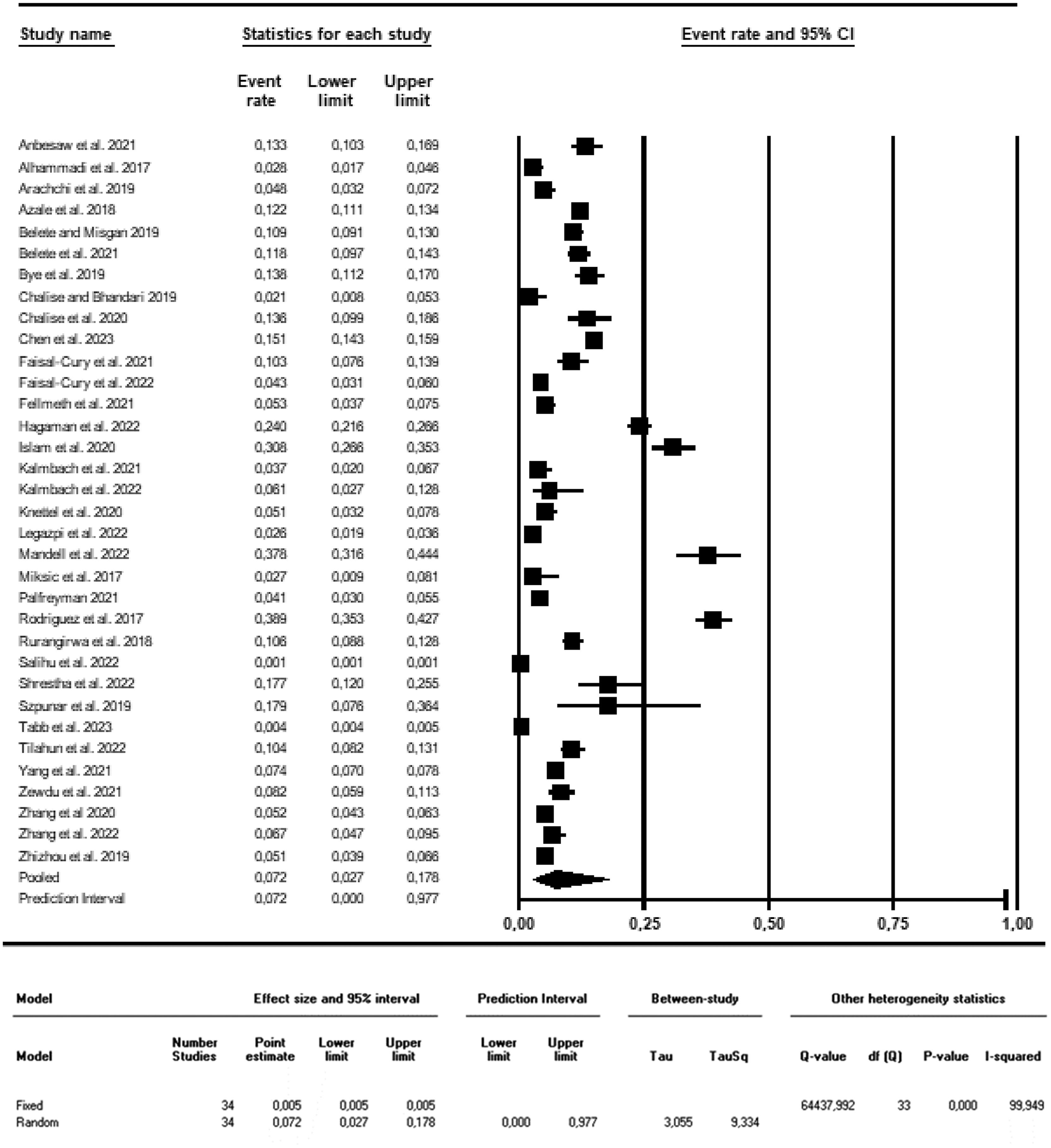

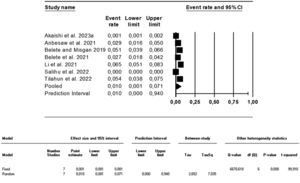

Suicidal ideation/ thoughtIn 34 of the studies, results of suicidal ideation/suicidal thoughts in the pregnancy and postpartum periods were reported.26,27,29,36–46,48–52,54-64,66–69 According to the synthesized results of these studies, the prevalence of suicidal ideation/suicidal thoughts was found to be 7.2 % (95 % CI, 0.03–0.18; I2= 99.95; Fig. 4). This rate was 6.3 % (95 % CI, 0.02–0.19; I2= 99.93) in the pre-pandemic period and 11.3 % (95 % CI, 0.08–0.17; I2= 99.90) in the pandemic period. In addition, this rate was 6.1 % during pregnancy (95 % CI, 0.02–0.20; I2= 99.95), 9.2 % in the postpartum period (95 % CI, 0.07–0.12; I2= 95.89), 17.5 % in high-risk groups (95 % CI, 0.07–0.36; I2= 97.87) and 6.1 % in low-risk groups (95 % CI, 0.02–0.16; I2= 99.95). However, meta-regression made with these moderator variables showed that this results was not statistically significant (respectively, z = 1.14, p = 0.25; z= −1.26, p = 0.21; z= −0.49, p = 0.63; Fig. 3b and e).

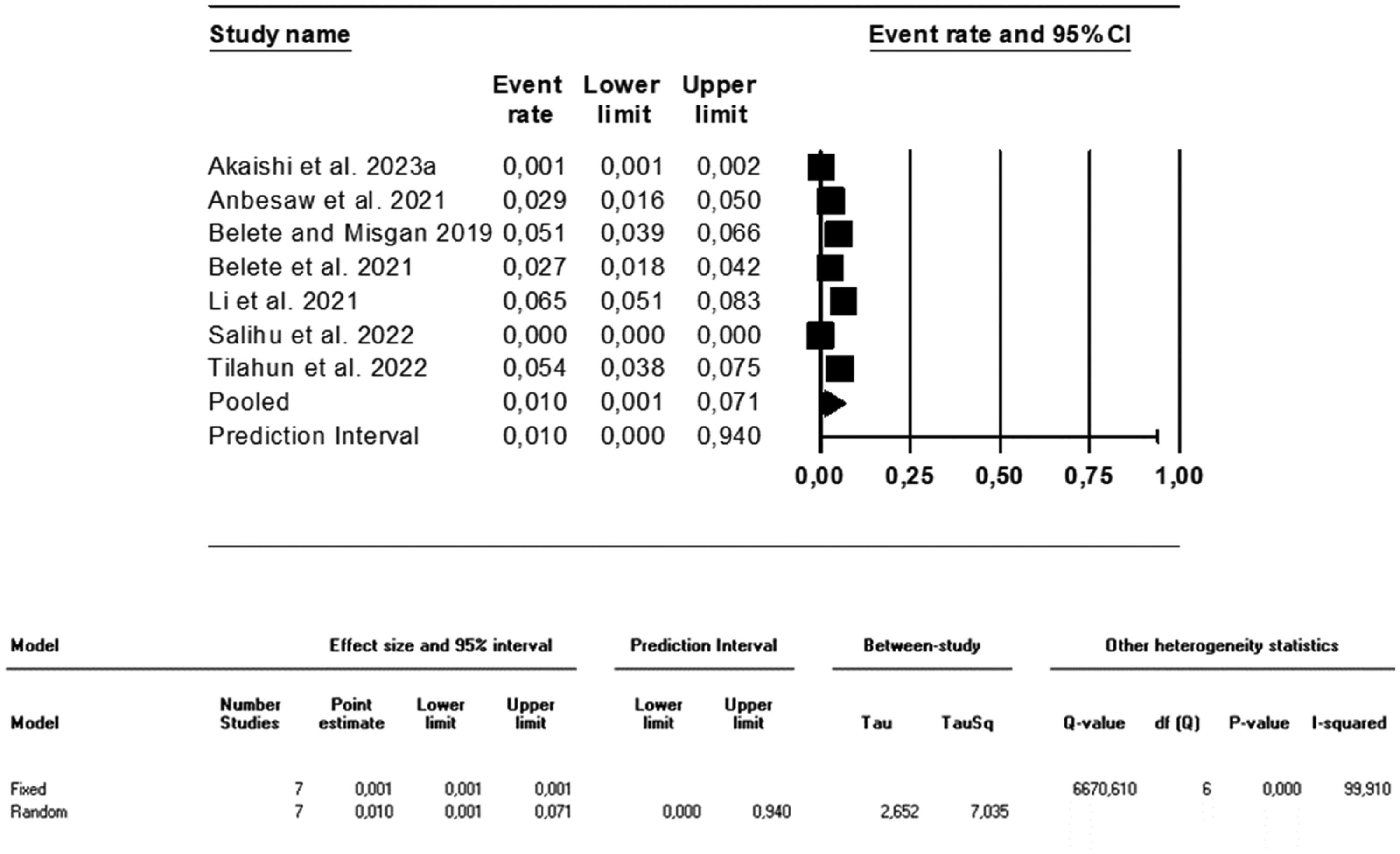

Suicide attemptsSeven studies had results of suicide attempts.26,51–54,65,67 Poled results of these studies sow that the rate of suicide attempts was 1 % (95 % CI, 0.00–0.07; I2= 99.91; Fig. 5). This rate was 0.5 % during pregnancy (95 % CI, 0.00–0.05; I2= 99.92), 0.7 % in the postpartum period (95 % CI, 0.00–0.38; I2= 99.88), 1.4 % in the pre-pandemic period (95 % CI, 0.00–0.64; I2= 99.95) and 3.6 % in the pandemic period (95 % CI, 0.02–0.06; I2= 72.83). Meta-regression made with the moderator variables of the pandemic period, having high risk and perinatal periods showed that there was no statistically significant effect of moderator variables on suicidal behavior (respectively, z = 0.63, p = 0.53; z= −1.46, p = 0.15; z= −1.28, p = 0.20; Fig. 3c and f).

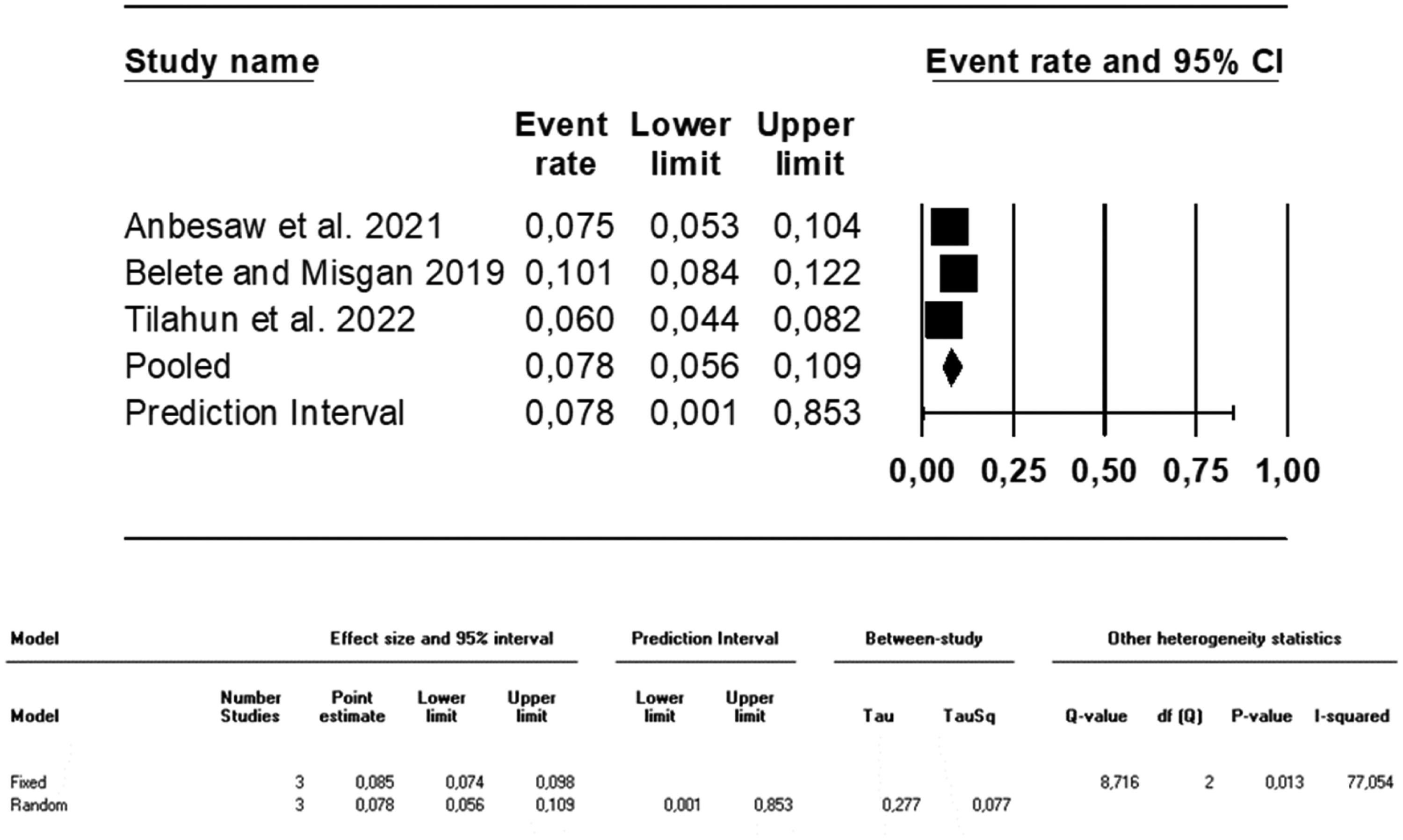

Suicide plansThree studies reported the results of suicide plans during pregnancy and postpartum periods.26,51,67 Pooled results of this studies showed that the rate of suicide plans during these periods was 7.8 % (95 % CI, 0.06–0.11; I2= 77.05; Fig. 6). This rate was 6.6 % during pandemic (95 % CI, 0.05–0.08; I2= 00.00), 10 % in the pre-pandemic period (95 % CI, 0.08–0.12; I2= 00.00), 7.5 % in the pregnancy (95 % CI, 0.05–0.10; I2= 00.00) and 8.8 % in the postpartum period (95 % CI, 0.08–0.10; I2= 87.50). No completed suicide cases were reported in any of the studies.

Publication bias between the studiesIn the data sets created on suicidal behavior and suicidal ideation/thought during the meta-analysis of this study, the publication bias between studies was statistically significant (suicidal behavior: t = 2.99, df: 4, p = 0.04; suicidal ideation/thought: t = 4.21, df: 32, p < 0.001), and it was not statistically significant for suicidal attempt (t = 1.25, df: 5, p = 0.27) and suicidal plan (t = 1.97, df: 1, p = 0.30; Fig. 7).

Narrative synthesis: factors associated with suicidal behaviorData on factors affecting suicidal behavior were reported in 25 of the studies included in this systematic review.26,27,40,45–48,50–53,55,57–63,65–69,70 According to the results of these studies, suicidal behaviors were more seen in individuals who had mental health problems, insomnia, a history of different forms of violence, younger age, unmarried, low education and income level, unemployed, first pregnancy, an unplanned pregnancy, history of abortion and trauma, assisted reproduction, a baby with health problems, bonding impairment, a habit of khat chewing, poor health status and social support, HIV-positive, country region, immigrant, black race, lower gestasyonel age, marital and sexual dissatisfaction (Table 1).

DiscussionThis systematic review and meta-analysis presents the synthesized results of 38 studies on the frequency of suicidal behavior and ideation during pregnancy and the postpartum period, its change in the COVID-19 pandemic, and related factors. The results obtained are valuable in terms of revealing comprehensive and up-to-date information on the subject.

In this meta-analysis, it was found that suicidal behavior was quite common (5.1 %) in women during pregnancy and postpartum period. A review of the literature on the topic indicated that the rate of suicidal behavior varied between 3 % and 33 %.6,12,16,24 It was thought that the reason for these prevalence differences might have been due to the different socio-cultural characteristics of the sample groups in which the studies were conducted, the development levels and cultural characteristics of the countries, their religious beliefs, and the structural differences of the measurement tools used in the studies.

In this study, it was determined that a significant portion of women (7.2 %) in pregnancy and postpartum periods had suicidal ideation/thoughts. The rate of suicidal ideation/thoughts was reported to vary between 2 % and 27.5 % in some other studies.6,22,24,71 The reason why suicidal ideation/thoughts were reported at different rates in studies can be explained by the different characteristics of the sample groups in which the studies were conducted and the differences in the measurement tools used in the studies.

In this systematic review, it was found that the rates of suicide attempts and suicide plans were quite common in the pregnancy and postpartum periods (1 % and 7.8 %, respectively). Asadpoor et al.,72 found that 2.7 % of women with pregnancy had a history of suicide attempts. Amiri and Behnezhad6 stated that the prevalence of suicide attempt was 4 % in the postpartum period. This difference in results may be related to the place of study and social characteristics.

In this study, it was determined that the prevalences of suicidal behavior, ideation/thoughts and attempt during pregnancy and postpartum increased depending on the pandemic process. Similarly, studies conducted in recent years have reported that the prevalence of mental illnesses increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.10,73–76 Yang et al.,29 reported that the self-harm/suicidal thoughts of women with pregnancy were slightly higher than the prevalence rate reported before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the fact that the number of studies conducted during the pandemic period is less indicates the need for more studies on the subject, and the results may vary depending on this situation.

In this study, it was observed that the prevalence of suicidal behavior, thoughts/thoughts, and attempts in the postpartum period was higher than during pregnancy. No systematic review reporting similar results for both periods was found. However, in a systematic review of postpartum women6 and pregnant women,3 higher rates were reported than our study results. These results may show that both periods, pregnancy and postpartum, are sensitive periods in the care service delivery process and should be considered together with additional risk factors.

In this review, it was determined that there are many physical, socio-cultural, psychological and economic factors associated with suicidal behavior and that these factors vary according to social characteristics. Our study findings are consistent with the findings in the literature.3,11 Some studies in the literature indicated that suicidal behavior was increased by younger age,77,78 unemployment,78 low education,16,77 low income,18,24 unplanned pregnancy,16,79 all forms of violence,11,16,23,24 physical and mental disorders,11,24,71 health problems in the baby,11 stigma,21,78 and lack of general support,11,16,71 but that it was decreased by older age72 and friend support.16,65 Contrary to our study findings, some studies showed older age,72 multiparity,24,72 and higher education71 increased suicide ideation. Social support is the strongest protective factor against suicide.65,79 Considering these high risk factors in the planning and delivery of health services in the perinatal period may contribute to the protection and development of mother-infant health.

In this systematic review, no completed suicide cases were reported in any of the studies. Contrary to this information, maternal suicide ratio is estimated to be 3.7 per 100,000 live births for the period 1980–200, especially violent suicide methods were common during the first 6 months postpartum in Sweden.80 In the United States a peripartum suicide rate of 2.0 per 100,000 live births for 17 pooled states was reported for the period 2003–2007.81 For Ontario (Canada), according to death records (1994–2008), a perinatal suicide rate of about 2.58 per 100,000 live births, with suicide accounting for 51 (5.3 %) of 966 perinatal deaths was reported.82 A study conducted in Taiwan using medical and death data of almost all pregnant women for the period 2002–2012 reported a total of 139 suicide attempts and 95 cases of completed suicide.83 In a retrospective study conducted in Austria between 2004 and 2017, 10 suicide cases were detected during pregnancy and in the first year after birth, and a maternal suicide rate of 0.89 per 100,000 birth events was reported.84 Even though this information was not reported in the studies we included in our meta-analysis, this information shows that completed suicide cases in the pregnancy and postpartum period are significant. Based on this information, we think that reporting completed suicides during pregnancy and the postpartum period is important and that researchers on this subject should be encourage.

Stregths and limitations of the reviewThe studies examined in this systematic review have wide literature review sources, up-to-date quality evaluation tools, and high-quality evaluation scores, which make up the strength of the study. The large total sample size combined in this meta-analysis is another strength of the study, which strengthens the results of the study. However, suicidal behavior was assessed with different scales and defined with different concepts in the studies, which constituted the limitation of the study. To control this effect, the meta-analysis was conducted taking into account the international conceptual definition, and the findings were reported accordingly. Another limitation of this study is that some studies were conducted with women with HIV (+), adolescents, veterans and khat chewing habits, which can be defined as a strong contributing variable for suicidal behavior. In our study, meta-regression was performed to examine the effect of these variables and the findings are presented. Also, the low homogeneity between studies in all meta-analyses conducted is another limitation that may weaken the power of the study. To control this situation, the Random Effect model was chosen in the analyses in which heterogeneity between studies was high.

ConclusionThis study revealed that the prevalence of suicidal suicidal behavior, defined as suicidal ideation/thought, attempt and plan, is common in women in the prenatal period, and that it increases during pregnancy and during the pandemic period in addition to many risk factors. These results support the results of previous studies. Based on these results, it can be suggested that this information be taken into account in the planning and delivery of prenatal care services, and that follow-up and care services should be organized in a way that will reduce the related high risk factors, prevent and improve health, and provide early diagnosis and intervention. In addition, it may be recommended to conduct studies that include current researches, which will expand the scope of the results of this study and enable more comprehensive information to be revealed.

CRediT authorship contribution statementZekiye Karaçam: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. Ezgi Sarı: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Rüveyda Yüksel: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Hülya Arslantaş: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization.