The objective of this work was to analyse the postoperative clinical results of patients surgically treated for colorectal cancer in relation to the results of the preoperative comprehensive geriatric evaluation.

MethodsObservational study in which postoperative morbidity and mortality at 30 and 90 days were analysed in a cohort of patients surgically treated for colorectal cancer according to age groups: group 1) between 75 and 79 years old; group 2) between 80 and 84 years old, and group 3) ≥85 years old. In addition to the anaesthetic risk assessment, patients were assessed with the Karnofsky, Barthel and Pfeiffer indexes. Mortality at 30 and 90 days after surgery was analysed in relation to the results of the comprehensive evaluation.

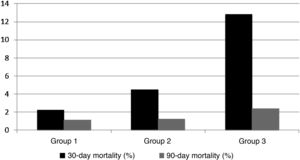

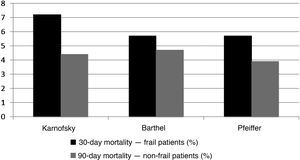

ResultsA total of 227 patients with colorectal cancer were included in the study period: 91 in group 1, 89 in group 2 and 47 in group 3. There were statistically significant differences in mortality at 30 days (p = 0,029) but not at 90 days after surgery, according to age groups. Mortality at 90 days was significantly higher in patients with worse scores on the Karnofsky and Barthel scales.

ConclusionsComprehensive geriatric assessment using different scales is a good tool to assess postoperative mortality in the mid-term postoperative period.

El objetivo de este trabajo fue analizar los resultados clínicos postoperatorios de los pacientes tratados quirúrgicamente por cáncer colorectal en relación a los resultados de la valoración geriátrica integral preoperatoria.

MétodosEstudio observacional en el que se analizó la morbimortalidad postoperatoria a los 30 y 90 días en una cohorte de pacientes intervenidos por cáncer colorrectal según grupos de edad: grupo 1) edad entre 75 y 79 años; grupo 2) entre los 80 y los 84 años, y grupo 3) ≥85 años. Además de la evaluación del riesgo anestésico, se evaluó a los pacientes con los índices de Karnofsky, Barthel y Pfeiffer. Se analizó la mortalidad a los 30 y 90 días de la cirugía en relación con los resultados de la evaluación integral.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 227 pacientes afectados de cáncer colorrectal en el periodo de estudio: 91 del grupo 1, 89 del grupo 2 y 47 del grupo 3. Hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la mortalidad a los 30 días (p = 0,029), pero no a los 90 días de la cirugía, según los grupos de edad. La mortalidad a los 90 días fue significativamente superior en los pacientes con peores puntuaciones en las escalas de Karnofsky y Barthel.

ConclusionesLa valoración geriátrica integral mediante distintas escalas es una buena herramienta para evaluar la mortalidad postoperatoria en el postoperatorio a medio plazo.

At present, an increase in life expectancy and a trend towards inversion of the demographic pyramid due to population ageing are observable realities. The population census taken in Spain every year has shown a gradual increase in inhabitants over 65 years of age, with a particularly substantial increase in the most advanced age groups: those over 75 and those over 80 years of age.1 This new epidemiological situation has brought about increased requirements for surgery on patients of very advanced age.2,3

Geriatric surgery has seen exponential development in recent years due to advances in various surgical and anaesthetic techniques, but above all due to better knowledge of ageing.4 All this has broadened the array of surgeries available to patients of very advanced age, with similar outcomes to those achieved in younger patient groups.5,6

Nevertheless, discussions about the risks and benefits of a surgical procedure in this stage of life can be very emotionally charged and touch on complex ethical matters.7 Perception, expectations and plans for how to manage the surgery often differ among patients (and their families), among surgeons and also among other physicians involved in caring for the patient.8

Geriatric patients characteristically have a higher likelihood of complicated perioperative events and adverse outcomes, as well as of non-immediate postoperative mortality weeks after the surgery.9 However, age in itself is not the only determining factor of additional risk in surgery; comorbidity and the overall functional status of the patient also matter greatly.10,11 This means that, in patients of very advanced age, a comprehensive geriatric evaluation with suitable testing is key to identifying the most frail, and therefore most vulnerable, patients in need of surgical treatment.12

There are published series of patients of advanced age having undergone surgery.13 Despite this, a limited number of them have included patients of very advanced ages who have undergone a geriatric evaluation and in whom the relationship of this with the morbidity/mortality results has been analysed.

The objective of this study was to analyse the clinical outcomes of surgery for colorectal cancer in patients of very advanced age (over 85) in relation to preoperative comprehensive geriatric evaluation values. The outcomes were also compared to younger groups of geriatric patients (over 75 and over 80 years old).

Material and methodsAn observational, prospective, comparative study was designed with the objective of analysing the postoperative clinical outcomes of a cohort of patients of very advanced age (compared to younger patients) who underwent surgery for colorectal cancer in the study period.

This study was a secondary analysis of a broader published study on the oncological and quality-of-life results in patients under 85 years of age.14 The study was submitted to and approved by the independent ethics committee at our centre.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaPatients 75 years of age and older diagnosed with colorectal cancer undergoing surgery with curative or palliative intent were enrolled. The patients who were enrolled had to understand the nature of the study and had to have signed an informed consent form. Patients with no histological confirmation of colorectal cancer, patients with inoperable colorectal cancer and patients who did not agree to surgical treatment were excluded from the study.

Specific geriatric assessment programmeA multidisciplinary team for the assessment and management of elderly patients was formed in our surgery department in 2011.15 This team comprised surgeons, an oncologist, internists specialising in geriatrics, an anaesthesiologist, a dietician and a social worker. In order to optimise the care of patients at the preoperative level, their performance status was evaluated with a comprehensive geriatric assessment, in addition to the usual preoperative assessment.

Surgical technique and postoperative managementIn most cases, the surgical technique considered included all the technical principles to be taken into account in a treatment with curative intent. However, the final decision was assessed by a patient-centred multidisciplinary committee. This assessment considered the patient's baseline characteristics, symptoms related to faecal incontinence at the time of diagnosis and risk of anastomotic dehiscence. The options for surgery were presented to the patient and a final decision was made jointly between the surgeon responsible and the patient (and their family). In patients with high surgical risk who required palliation of tumour-related symptoms, a segmental or palliative resection was proposed, with a lower risk of anastomotic dehiscence.

Preoperative and postoperative management included an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery programme16 adapted to each patient, involving early mobilisation and initiation of an oral diet six hours after surgery, and continued thereafter if tolerated. In accordance with the clinical practice guidelines for the period in which the patients were enrolled, they received antithrombotic prophylaxis with low–molecular-weight heparin.17

Study variablesBaseline characteristics of the patientsThe patients’ sociodemographic characteristics (age and sex) and surgical treatment were prospectively recorded. Scores on the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scale18 and Charlson Comorbidity Index19 enabled evaluation of anaesthetic risk and comorbidities for each group.

For the comprehensive geriatric assessment of the patients, their performance and cognitive status were studied. To this end, the Karnofsky Performance Scale20 and the Barthel Index21 were used, and the Pfeiffer questionnaire was applied to evaluate cognitive decline.22,23

The Karnofsky Performance Scale assesses their ability to perform routine activities and daily tasks, as well as self-care. The score ranges from 0 to 100. The greater the patient’s ability for going about activities, the higher the score. It was first reported for use in oncology patients, but thanks to its usefulness it is now applied in other diseases and in preoperative assessment. A Karnofsky Performance Scale score under 80 means that the patient lacks the autonomy to go about all his or her normal activities and active work.20

The Barthel Index is an instrument for functional assessment of a patient. Its results also range from 0 to 100, with 100 corresponding to maximum functional capacity for the activities of daily living. A Barthel Index score under 60 means that the patient has severe dependency and therefore is used as a cut-off point in some studies.21

The Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ), or simply the Pfeiffer questionnaire, is a tool that can be quickly applied with no special preparation, providing information on different cognitive areas, especially memory and orientation. It consists of 10 questions and is useful in elderly and illiterate people. Errors in the 10 items of the test were counted with the following meaning or interpretation: 0–2 errors — normal; 3–4 errors — mild cognitive decline; 5–7 errors — moderate decline; 8–10 errors — severe decline.23 In general, some studies also consider a Pfeiffer score with more than three errors to be a criterion for frailty.24

Postoperative outcomesPostoperative complications were reported using the Clavien-Dindo Classification,25 with scoring from I to V depending on severity and treatment required. Mortality 30 days after surgery and, as in other series of elderly patients, 90 days after surgery were also analysed.26

Statistical analysis and sample sizeThe minimum number of subjects per group was calculated, considering acceptance of an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.2 (in a bilateral test), which anticipated a 20% difference in 90-day mortality between groups, according to published series.27 The minimum sample size calculated was 46 patients per group.

Quantitative variables are presented in terms of mean ± standard deviation or median and ranges. Categorical variables are presented in terms of absolute numbers or percentages. The chi-squared test was used to compare differences in categorical variables (with Fisher’s exact test when necessary), and Student’s t test and/or analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used for continuous variables (if they followed the law of normality). To study the correlation between the functional assessment scales (the Karnofsky Performance Scale and the Barthel Index), Pearson’s correlation test was used. All p values reported were bilateral, and statistical significance was considered to have been achieved when the p value was less than or equal to 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® (version 21.0).

ResultsDuring the study period, 227 patients were enrolled: 91 patients 75–79 years of age (group 1), 89 patients 80–84 years of age (group 2) and, finally, 47 patients 85 of age and older (group 3).

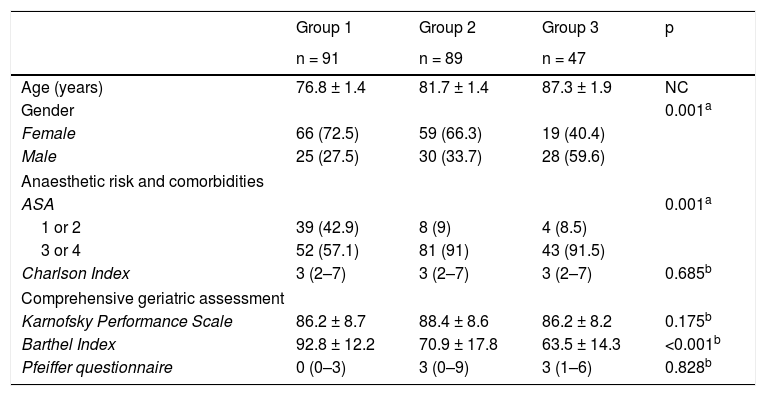

Characteristics of the patients enrolledTable 1 shows the general characteristics of the patients in each group. The proportions of men and women showed statistically significant differences between the groups (p = 0.001); there were more male patients than female patients in group 3 only. In addition, anaesthetic risk as measured by the ASA scale was higher in patients of advanced age and patients of very advanced age. These differences were also statistically significant (p = 0.001), but not when the Charlson Index was used to compare comorbidities between groups (p = 0.685).

Characteristics of the patients in each age group.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 91 | n = 89 | n = 47 | ||

| Age (years) | 76.8 ± 1.4 | 81.7 ± 1.4 | 87.3 ± 1.9 | NC |

| Gender | 0.001a | |||

| Female | 66 (72.5) | 59 (66.3) | 19 (40.4) | |

| Male | 25 (27.5) | 30 (33.7) | 28 (59.6) | |

| Anaesthetic risk and comorbidities | ||||

| ASA | 0.001a | |||

| 1 or 2 | 39 (42.9) | 8 (9) | 4 (8.5) | |

| 3 or 4 | 52 (57.1) | 81 (91) | 43 (91.5) | |

| Charlson Index | 3 (2–7) | 3 (2–7) | 3 (2–7) | 0.685b |

| Comprehensive geriatric assessment | ||||

| Karnofsky Performance Scale | 86.2 ± 8.7 | 88.4 ± 8.6 | 86.2 ± 8.2 | 0.175b |

| Barthel Index | 92.8 ± 12.2 | 70.9 ± 17.8 | 63.5 ± 14.3 | <0.001b |

| Pfeiffer questionnaire | 0 (0–3) | 3 (0–9) | 3 (1–6) | 0.828b |

NC: not compared.

Data are expressed in terms of mean ± standard deviation, absolute numbers (%) or median (range).

Group 1: 75–79 years old; Group 2: 80–84 years old; Group 3: 85 years and older.

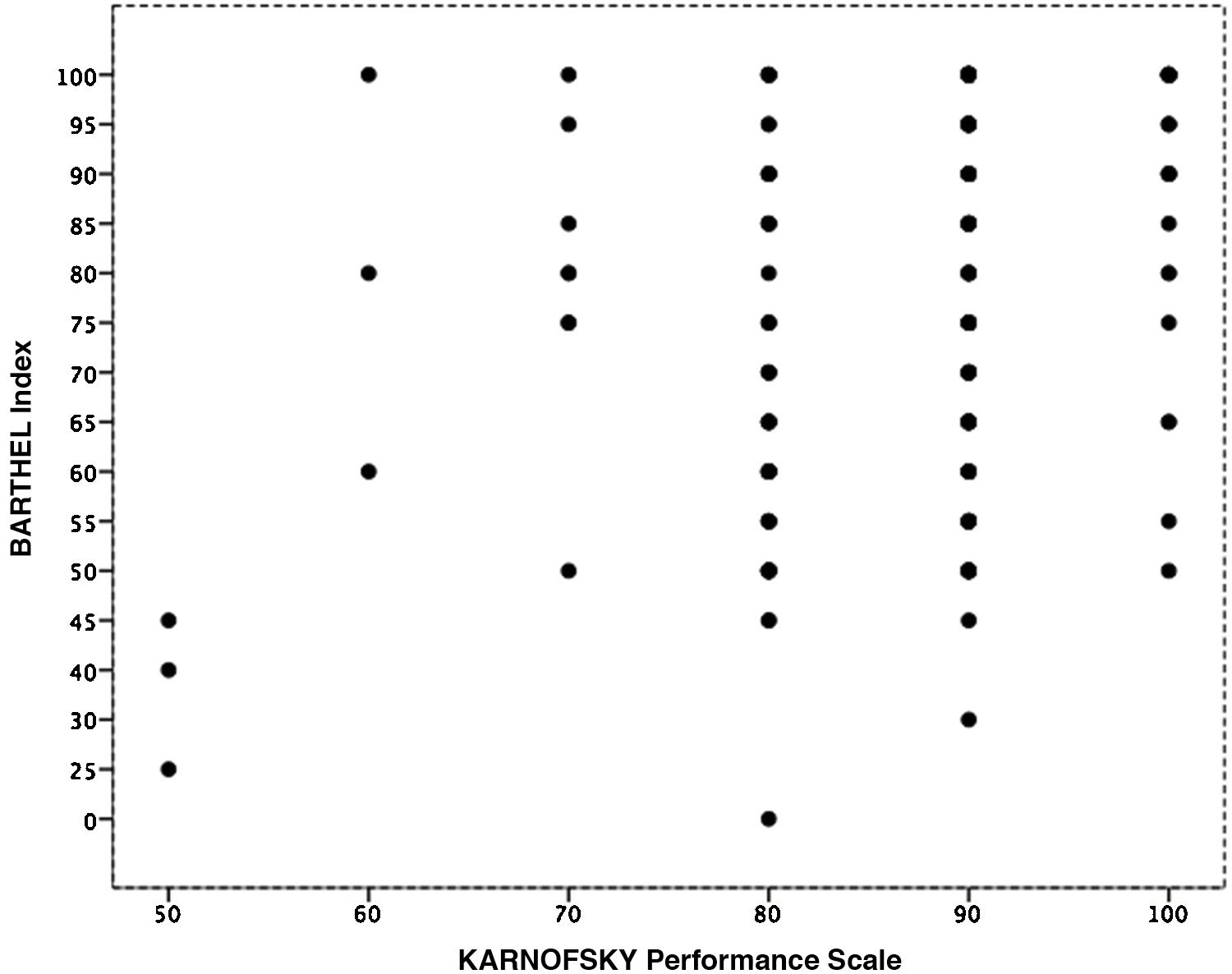

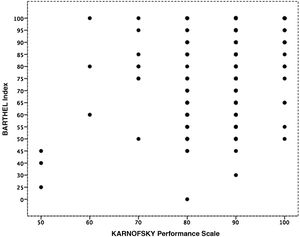

Table 1 also shows the results of the comprehensive geriatric assessment, when analysing the functional and cognitive capacity of the patients included in the study. Assessment using the Karnofsky Performance Scale, Barthel Index and Pfeiffer questionnaire revealed no statistically significant differences except in the Barthel Index values: scores on this index were lower in group 3 (p < 0.001). Despite these results, a statistically significant correlation was found between the two functional evaluation scales used, the Karnofsky Performance Scale and the Barthel Index (p < 0.001; Fig. 1).

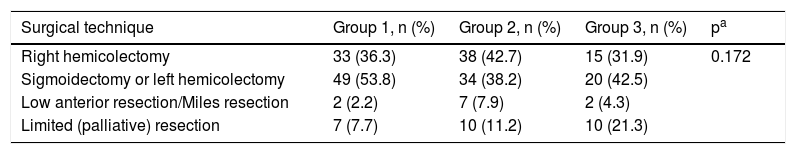

Table 2 shows the type of surgery performed by group. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in the type of surgery performed as a rule according to the tumour location. In some cases, with a higher frequency according to age, palliative surgery or partial resection was chosen, taking into account the patient’s signs and symptoms and the patient’s age.

Surgical technique used in each age group.

| Surgical technique | Group 1, n (%) | Group 2, n (%) | Group 3, n (%) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right hemicolectomy | 33 (36.3) | 38 (42.7) | 15 (31.9) | 0.172 |

| Sigmoidectomy or left hemicolectomy | 49 (53.8) | 34 (38.2) | 20 (42.5) | |

| Low anterior resection/Miles resection | 2 (2.2) | 7 (7.9) | 2 (4.3) | |

| Limited (palliative) resection | 7 (7.7) | 10 (11.2) | 10 (21.3) |

Group 1: 75–79 years old; Group 2: 80–84 years old; Group 3: 85 years and older.

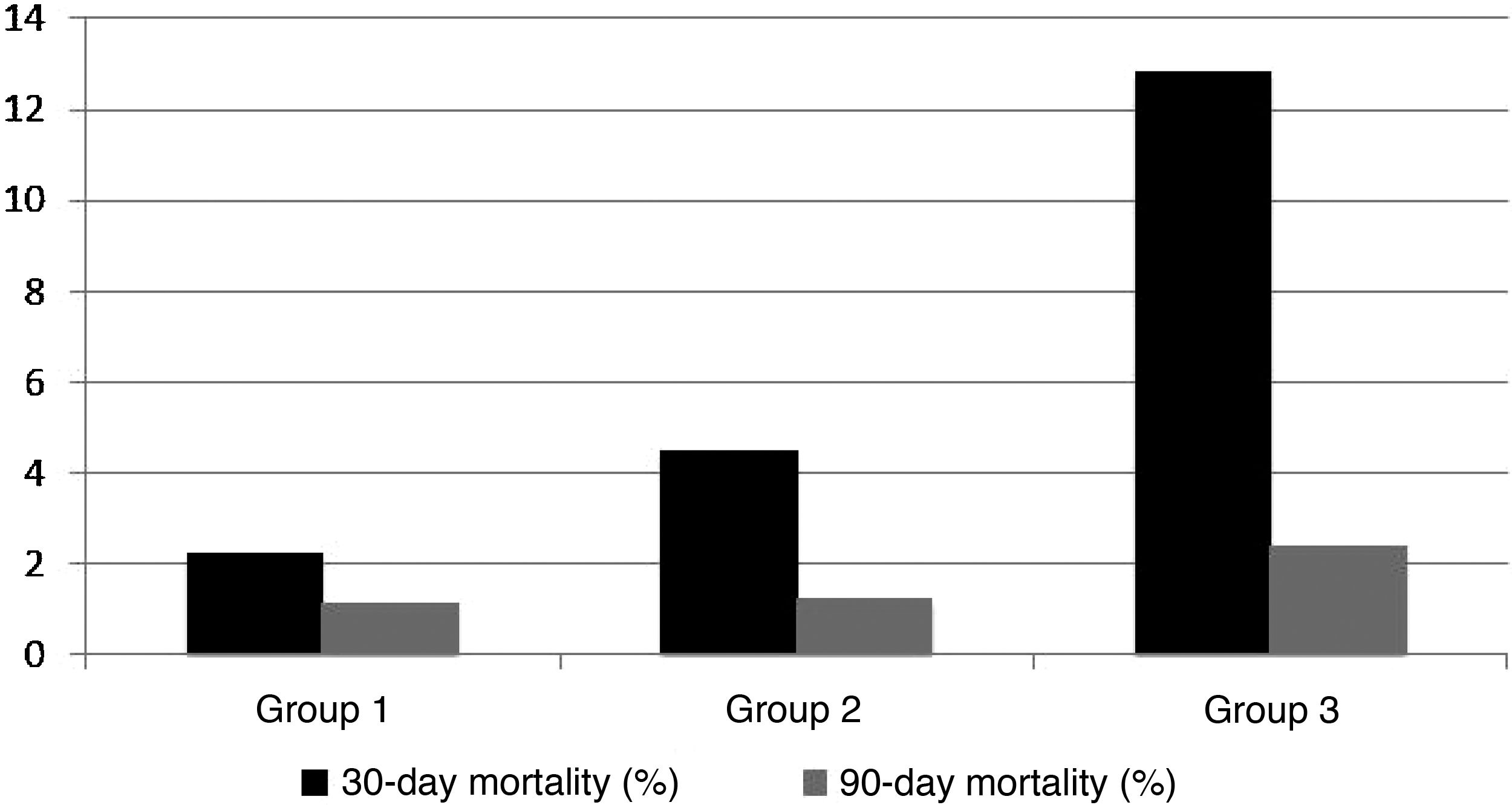

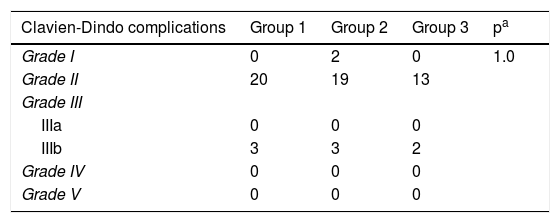

Postoperative complications are presented in Table 3. It can be seen that there were no differences between the three groups (Table 3). Concerning postoperative mortality, 12 patients died (5.2%) within 30 days after surgery (two in group 1, four in group 2 and six in group 3), and three patients (1.3%) died within 90 days after surgery (one patient in each group), as can be seen in percentages in Fig. 2. Between-group differences showed statistical significance only in 30-day mortality and not in 90-day mortality (p = 0.029 and p = 0.322, respectively).

Clavien-Dindo Classification of postoperative complications in each group.

| Clavien-Dindo complications | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade I | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1.0 |

| Grade II | 20 | 19 | 13 | |

| Grade III | ||||

| IIIa | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| IIIb | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| Grade IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Grade V | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Group 1: 75–79 years old; Group 2: 80–84 years old; Group 3: 85 years and older.

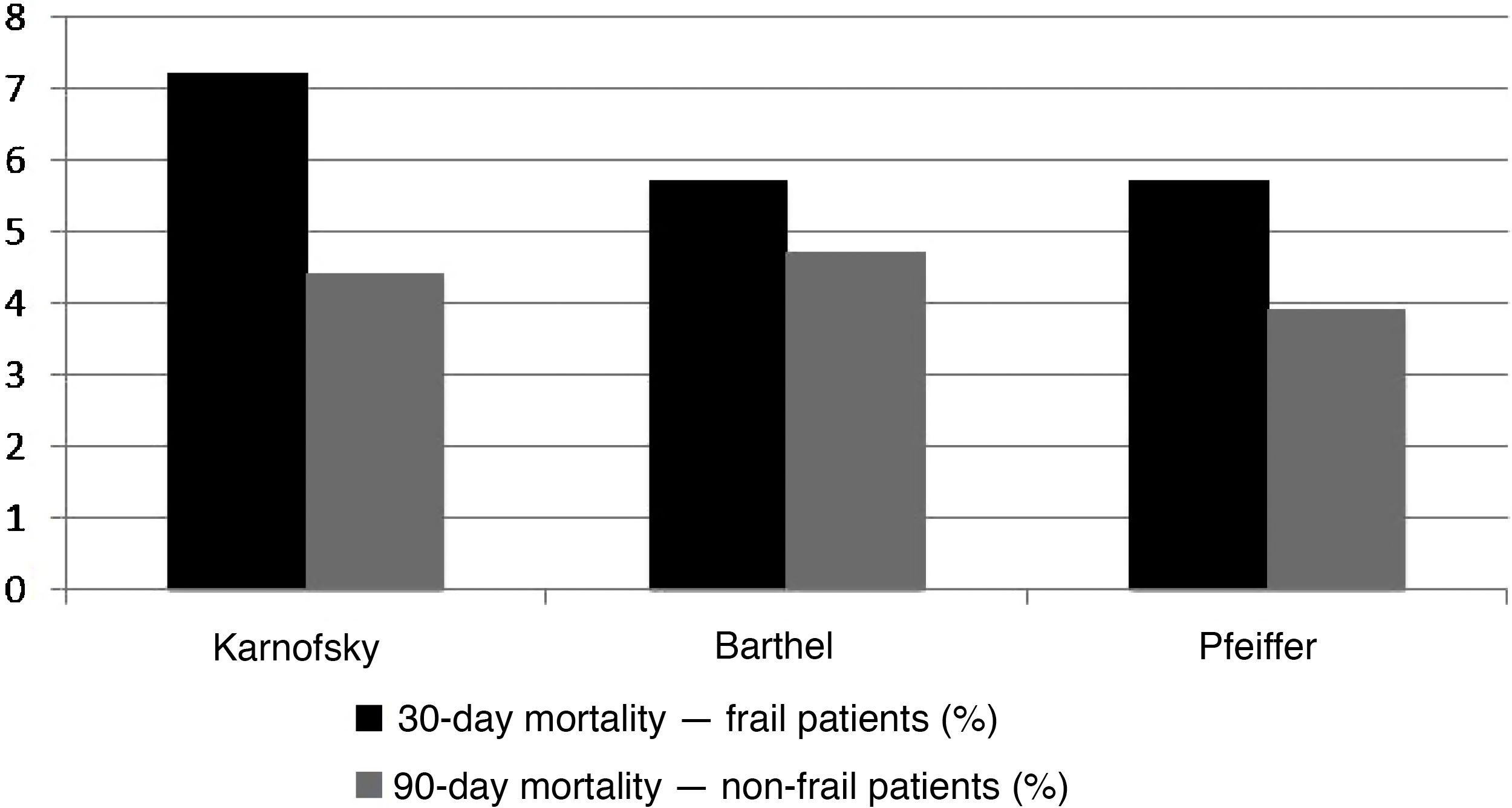

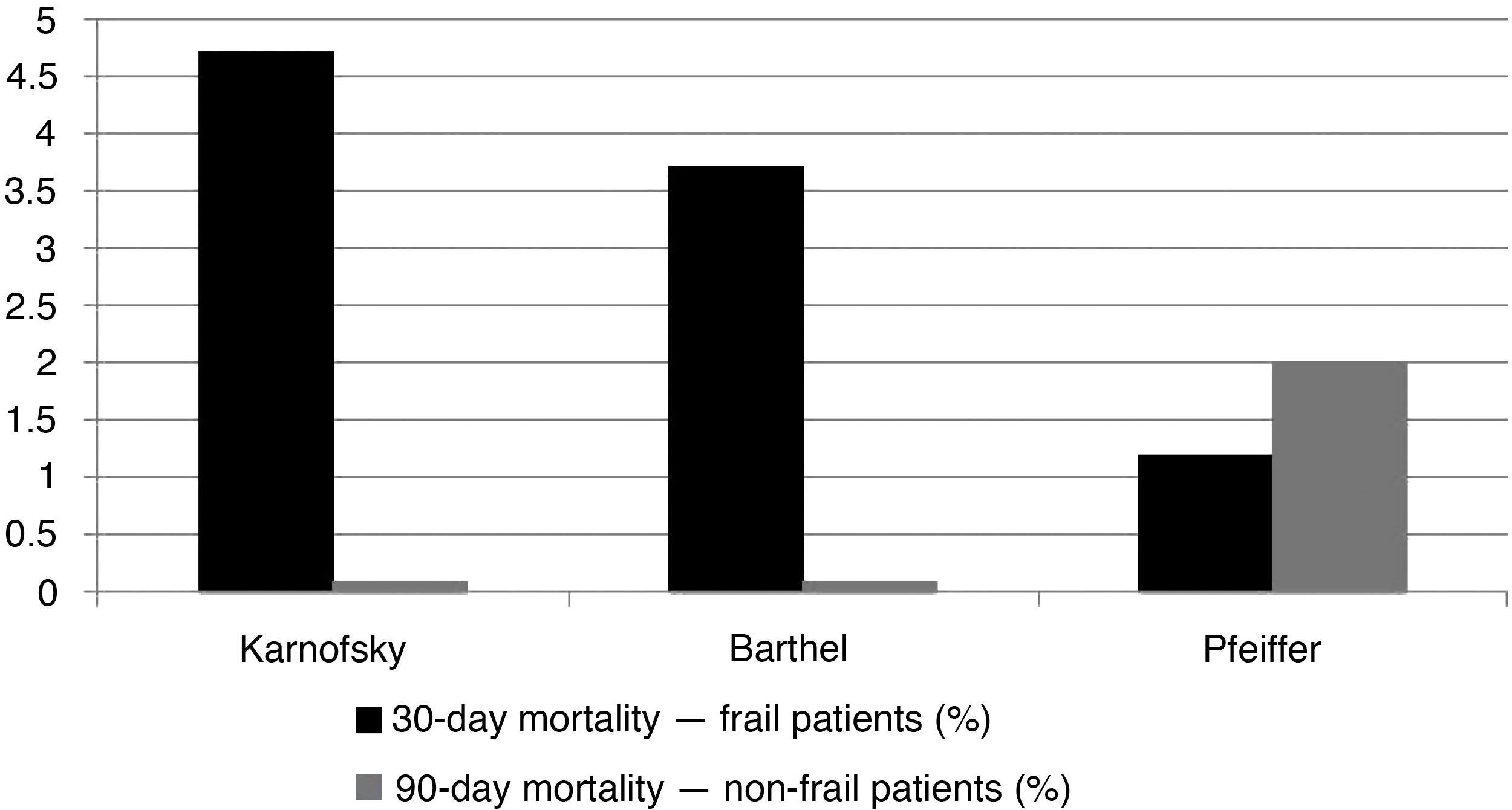

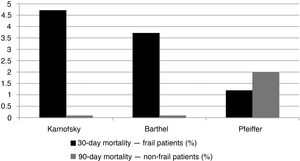

When we analysed the relationship between the results of the comprehensive geriatric evaluation questionnaires and the cut-off points for frailty, we found that, in the case of patients assessed as not frail with the Karnofsky Performance Scale and the Barthel Index, mortality was null, but with the Pfeiffer questionnaire, mortality was similar to the group assessed as frail (Fig. 4). Therefore, there was a statistically significant association between the two tests that assessed the performance status but not so much the mental status and postoperative mortality within 90 days of surgery (Karnofsky Performance Scale <80, p = 0.026; Barthel Index <60, p = 0.050; Pfeiffer questionnaire with more than three errors, p = 0.542), but not with immediate postoperative mortality within 30 days of surgery (Karnofsky Performance Scale <80, p = 0.519; Barthel Index <60, p = 0.735; Pfeiffer questionnaire with more than three errors, p = 1.0). These results are presented in graphs in Figs. 3 and 4.

Decision-making around surgical treatment of colorectal cancer in patients of advanced age remains a challenge for the healthcare community, in particular for surgeons, oncologists and geriatricians. In this study, we analysed immediate and medium-term postoperative outcomes in a cohort of patients of very advanced age with a diagnosis of colorectal cancer and the value of their comprehensive geriatric assessment. We found the preoperative geriatric evaluation to be a good tool for evaluating postoperative mortality within 90 days.

Evaluation of the characteristics of the patients in the three age groups highlighted that differences seen in the ASA classification were not observed with the Charlson Index (Table 1). We believe that comorbidity rates were not very high with the Charlson Index because patient selection was in relation to a surgical procedure. However, the ASA scale also considers age and anaesthetic risk, not just in relation to comorbidity.28,29 Another notable finding of the study was that only the Barthel Index was clearly inferior in the group of patients of very advanced age (over 85); the Karnofsky Performance Scale was not. Both tests serve to evaluate the functional status of people of advanced age, but the Barthel Index focuses more on basic activities of daily living, whereas the Karnofsky Performance scale concentrates on dependency.21,30 For this reason, the latter showed fewer differences between the age groups. Despite this, as a control of the value contributed by gathering information from the two tests, we wanted to observe the correlation between the two scales, which was statistically significant (Fig. 1). These differences between age groups confirmed the need for analysis by frailty found in the geriatric evaluation performed in this study (Figs. 3 and 4).

In our published series, 30-day mortality and 90-day mortality were 5.2% and 1.3%, respectively, among those who survived the first month of the postoperative period. This percentage was higher than overall mortality standards in elective colorectal surgery, which are around 1%–2%, but lower than other published series in patients of advanced age.24,27 One fact that must not be overlooked is that 30-day mortality was higher in patients of advanced age despite the comprehensive geriatric assessment. This might have been related to the performance of a more oncological surgery, as seen in Table 2 in the younger patients, or to data that were not analysed, such as nutritional status or haemoglobin levels.

In our experience, the results of the geriatric evaluation, specifically the Karnofsky Performance Scale and the Barthel Index, proved to be associated with higher 90-day mortality following surgery. These results have also been reproduced by more recent series and could be very useful for decision-making in these age groups if confirmed in multicentre studies or studies with larger numbers of cases.9

Geriatric evaluation does not delay the process between diagnosis and surgical treatment, as this period is determined by wait times in the colorectal cancer oncology care pathway, regardless of patient age (or preoperative evaluation).

According to the published literature, geriatric evaluation tests are probably more suitable for evaluating physiologic reserve, not the probability of immediate complications (morbidity), which are more related to the development of complications associated with surgery (e.g. dehiscence of the colorectal anastomosis). That is why the evaluation seems to have a medium- or long-term impact on a surgical intervention. Perhaps this fact could explain the impact that their outcomes have on 90-day mortality both in our results and in those of other series.9

Another interesting aspect, though one that goes beyond the scope of the debate that we would like to generate with our study, are the limits, if any, for treatment in patients of very advanced age. Certainly there are ethical aspects that must be considered, and there is no doubt about the value of making a decision jointly with the patient and their family, regarding the possibility of having to perform a surgical intervention on the patient if the probability of mortality in the short and medium term is not very high. In our experience, however, postoperative mortality (up to 90 days) was similar or even better than in other published series.24

Nevertheless, after improving efforts in patient selection, and after many efforts to optimise postoperative management through Enhanced Recovery After Surgery and fast-track programmes,16 there is now scientific evidence to show that the enhancement of preoperative conditions by means of preoperative preparation programmes improves postoperative clinical outcomes in major surgical procedures.31 This initiative includes carrying out a general optimisation of the patient both at a nutritional level and though physical exercise or specific respiratory physiotherapy programmes, and would be particularly appropriate in the management of geriatric patients.32 Therefore, in future studies, a comprehensive geriatric assessment would form part of the entire process which could aid in more precise selection of the most suitable preoperative preparation programmes by patient type.

Our study is one of the only published studies that includes a cohort of patients of both advanced and very advanced age in whom a substantial part of the comprehensive geriatric assessment was conducted with two functional tests and one cognitive decline test. This study is a secondary analysis of a broad study of a cohort of patients who underwent an overall evaluation and had a single very common disease, colorectal cancer.14 However, this study also had certain limitations and its results should be analysed with these in mind. The first limitation was that we did not evaluate patients with a single test that unifies all the functional aspects and specific clinical aspects of surgical risk, which seems to be very useful. The American College of Surgeons recently launched an initiative for optimising the management of these patients with the use of a surgical risk prediction system in this population of advanced age.33 We also were unable to analyse the data from the evaluation of other important aspects such as nutritional status, and we lacked information from patients who ultimately were not treated with surgery.9 Finally, another limitation was the difficulty in defining the concept of frailty without using specific tests for this purpose.11 Therefore, we defined cut-off points based on previous published experiences,24 and considered them to be: less than 80 points on the Karnofsky Performance scale, less than 70 points on the Barthel Index and more than 3 errors in the cognitive evaluation of the Pfeiffer questionnaire.

In conclusion, according to our experience, a comprehensive geriatric assessment using different scales is a good tool for determining postoperative mortality in the medium-term postoperative period. A prospective study design enabled us to assess the value of this geriatric evaluation in the selection of patients for each preoperative preparation programme.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This study was presented orally at the 32nd Congreso Nacional de Cirugía [Spanish National Surgery Conference] from 12 to 15 November 2018.

Please cite this article as: Sentí S, Gené C, Troya J, Pacho C, Nuñez R, Parrales M, et al. Valoración geriátrica integral: influencia en los resultados clínicos de la cirugía colorrectal en pacientes de edad muy avanzada. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:472–480.