Zenker's diverticulum (ZD) is a protrusion of the hypopharyngeal mucosa with a prevalence of 2/100,000 inhabitants. The symptoms of the patients determine the need for treatment, which can be surgical or endoscopic. The latter, known as endoscopic septotomy or diverticulotomy (ED), this involves dissecting the diverticular septum, which can be performed with different dissection devices.

AimThe aim of our study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ED with Stag-Beetle Knife device, as well as to conduct a literature review to assess the position of the technique in the current scientific panorama.

Material and methodsDescriptive retrospective study that includes patients who underwent ED with SB-Knife between June 2017 and February 2020. Literature review of the available evidence between January 2013 and April 2020 of ED with SB-Knife technique and its variants.

ResultsTwelve patients (66% male) with a median age of 70.5 years were collected. The median size of diverticular was 32.5 mm and complete remission was observed in 75% of the cases. Fourteen interventions were performed with a technical success of 92.8%. There were no serious complications. A literature review was carried out, finding 13 papers, of which 8 were finally included (6 retrospective studies, a series of cases and a clinical case).

ConclusionBased on our experience and the reviewed literature, we consider ED with SB-Knife is a safe, effective and reproducible technique, and may be a better alternative to surgery in patients with ZD.

El divertículo de Zenker (DZ) es una protrusión de la mucosa hipofaríngea con una prevalencia de 2/100.000 habitantes. La clínica condiciona la necesidad de tratamiento, pudiendo ser quirúrgico o endoscópico. Este último, denominado septotomía o diverticulotomía endoscópica (DE), consiste en la disección del septo diverticular, pudiendo realizarse con distintos dispositivos disectores.

ObjetivoEl objetivo del estudio es evaluar la eficacia y seguridad de la DE mediante el dispositivo Stag-Beetle Knife, así como realizar una revisión de la literatura para valorar el posicionamiento de la técnica en el panorama científico actual.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo descriptivo que incluye pacientes intervenidos mediante DE con SB-Knife entre junio de 2017 y febrero de 2020. Revisión de la literatura de la evidencia disponible entre enero de 2013 y abril 2020 de la DE mediante la técnica con SB-Knife y sus variantes.

ResultadosSe recopilaron 12 pacientes (66% hombres) con una mediana de 70,5 años. El tamaño diverticular fue de 32,5 mm de mediana y la remisión completa se objetivó en el 75% de los casos. Se realizaron 14 intervenciones con un éxito técnico de 92,8%. No se produjeron complicaciones graves. Se realizó una revisión de la literatura encontrando 13 trabajos de los cuales se incluyeron finalmente 8 (seis estudios retrospectivos, una serie de casos y un caso clínico).

ConclusionesEn base a nuestra experiencia y a la bibliografía revisada, consideramos que la DE mediante SB-Knife es una técnica segura, eficaz y reproducible, pudiendo ser una mejor alternativa a la cirugía en pacientes con DZ.

Zenker's diverticulum (ZD), also known as pharyngeal pouch, is an acquired alteration consisting of the sacculation of the mucosal and submucosal layers of the pharyngoesophageal junction. It is located in the posterior face of the aforementioned wall, at Killian's triangle, in a virtual space delimited by the oblique fibres of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle and the transverse fibres of the cricopharyngeal muscle. First described in the 18th century, it was not until the mid-19th century that Friedrich Albert von Zenker characterised it and theorised about its pathophysiology.1

Among the causes that lead to its appearance, it is generally accepted that there is an alteration in the aperture of the upper oesophageal sphincter (UOS), which has been shown in several manometric tests.2 In recent years, it has been described as a multifactorial disorder, with a loss of muscle fibres that are replaced by collagen fibres appearing in anatomopathological studies. This process appears to be linked to ageing, genetic factors and to gastroesophageal reflux.3,4

Although the pathophysiology is not fully understood, the likeliest hypothesis is that ZD develops as a result of increased intraluminal pressure in the oropharynx during swallowing caused by inadequate relaxation of the cricopharyngeal muscle, and therefore of the UOS, giving rise to an outpouching of the pharyngoesophageal wall at the weakest area: Killian's triangle.2

ZD typically manifests at advanced ages, particularly between the age of 60 and 80, with a 1.5:1 predominance in men compared to women. The estimated annual incidence is 2/100,000 people, with a prevalence of between 0.01% and 0.11%, which is likely to increase in the coming years due to population ageing.4

The classic symptoms of ZD are progressive oropharyngeal dysphagia both for solids and liquids, regurgitation, chronic cough, repeat bronchoaspirations, halitosis and sensation of cervical mass. Complications range from infection of the diverticulum and bleeding to iatrogenic perforation. The malignisation of the diverticulum, while extremely uncommon, is described with an annual incidence of up to 0.5%.1,5

Barium swallow is the radiological study of choice for diagnosing and determining size and should be complemented by a careful endoscopic exploration to rule out malignancy.4 The treatments developed include surgical techniques (diverticulectomy or diverticulopexy with or without myotomy), myotomy with rigid endoscope and surgery with flexible endoscope. Currently, only procedures that involve myotomy are considered on account of the high risk of medium- to long-term relapse due to the pathophysiology of ZD.6

In recent years, the different therapeutic options have tended towards flexible endoscopic procedures as opposed to the classic surgical techniques, with a parallel reduction in associated morbidity and mortality.7,8 Overall, and irrespective of the procedure employed, defining the disappearance of dysphagia as a fundamental objective of the procedure, clinical success ratios of between 84% and 100% have been reported, with some cases requiring more than one session to achieve these outcomes.9–12

The objective of our study was to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of endoscopic diverticulotomy (ED) by SB-Knife™ by collecting epidemiological data, as well as the clinical, morphological and radiological characteristics and treatments performed on all patients diagnosed with ZD at our centre. A literature review was also performed, gathering the available evidence in order to assess the technique's positioning in the current scientific scenario. The aim of collecting these data was to provide information about the technique performed, identifying strengths and areas for improvement in our daily clinical practice.

Materials and methodsDescriptive studyThis was a descriptive retrospective study of patients who underwent endoscopic diverticulotomy (ED) at the Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria of Malaga between June 2017 and February 2020. All the patients underwent a barium swallow to assess ZD, including all new patients diagnosed at our centre. All the procedures were performed by expert endoscopists (GA or IL). The technique was performed in the operating theatre under deep sedation or general anaesthesia at the anaesthetist's discretion and with antibiotic prophylaxis in all cases.

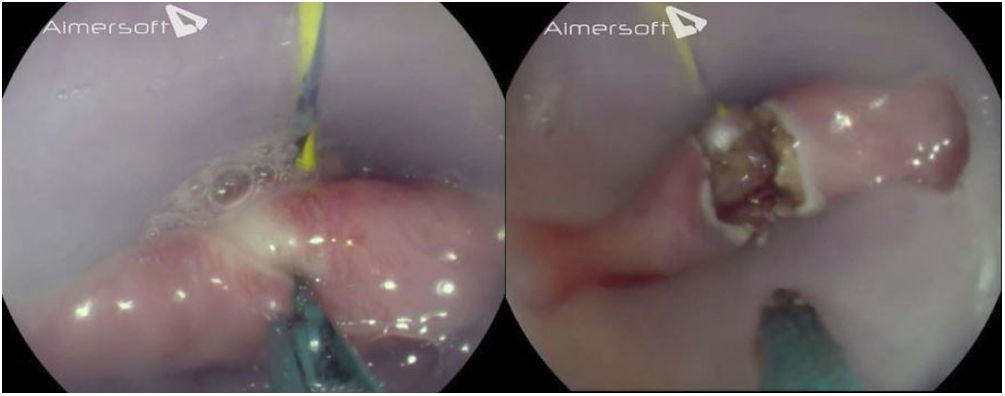

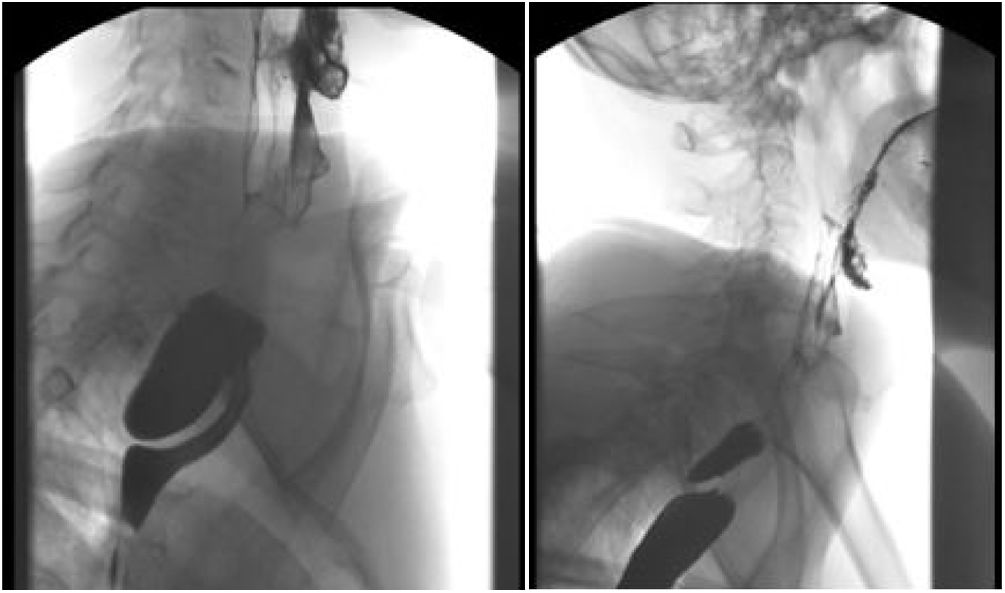

The surgery consisted of inserting the endoscope to locate the diverticulum and placing a guide wire towards the stomach. The 30 cm long and 22 mm diameter bivalve diverticuloscope (Zenker’ZDO-22-30, Cook Medical, Limerick) with the guide wire located on a manually made orifice is inserted into the larger valve, which is placed in the lumen of the oesophagus, and the smaller one in the diverticular lumen, thus exposing the diverticular septum between both valves (Fig. 1). This step can be performed directly without the need for a guide wire at the endoscopist's discretion. Subsequently, the dissection or septotomy of the cricopharyngeal muscle is performed using the SB-Knife™ Jr MD-47703W (Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Tokyo, Japan) with a single incision controlled by endoscopic vision, and concludes with the placement of haemostatic clips to prevent delayed bleeding and/or perforation (Figs. 2 and 3). If there are no complications, liquid tolerance is initiated and patients are discharged after 24 h. The patients are then monitored on an outpatient basis for six months (Fig. 4). Technical success was defined as the performance of the septotomy with a single incision without immediate complications, and clinical success as the disappearance of the patient's symptoms. The descriptive study was expressed in the form of the mean, median, interquartile range (IQR) and range.

This study was conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (Fortaleza 2013) and Good Clinical Practice. Personal data were processed according to REGULATION (EU) 2016/679 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. No patient informed consents were required as only medical histories were reviewed.

Literature reviewThe PubMed, Embase and Cochrane databases were consulted to identify articles published between January 2013 and April 2020. The terms used for the search were: («Zenker Diverticulum» OR «Zenker´s Diverticulum» OR «Zenker´s Diverticula» OR «Zenker Diverticula» OR «Pharyngeal Pouch») AND («Endoscopy» OR «Endoscopic») AND («SB-Knife™» OR «Stag Beetle Knife™» OR «Scissors»). In addition, other relevant bibliographic references in these articles that we might have missed during the literature review were also checked. The search was not limited by the language of the publication.

The following variables were collected: demographic characteristics (year, country of publication, size and mean age of the sample), the characteristics of the diverticulum, type of technique, assistance devices, clinical response, procedure complications, post-procedure recurrence, number of procedures per patient, the use of prophylactic clips and antibiotic therapy, the duration of the procedure, the type of anaesthetic administered and mean post-procedure hospital stay.

ResultsDescriptive studyTwelve (12) patients underwent surgery (Table 1), eight of whom were male (66%). The median age was 70.5 years, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 13.5 and a range of 44−83. None of the patients had a family history of ZD or a personal history of surgery, cervical or vertebral trauma. None of them had received any other previous treatment for ZD.

Patient characteristics and outcome.

| Total, n | 12 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 8 (66.6) |

| Female | 4 (33.3) |

| Age years, median (IQR, range) | 70.5 (13.5; 44−83) |

| Clinical symptoms, n (%) | |

| Dysphagia | 12 (100) |

| Regurgitation | 2 (16.6) |

| Heartburn | 2 (16.6) |

| Cough | 1 (8.3) |

| Median diverticulum size (IQR, range), mm | 32.5 (20; 10−50) |

| Complete postoperative remission, n (%) | 9 (75) |

| Clinical recurrence, n (%) | 3 (25) |

IQR, interquartile range; mm, millimetres; n, number.

The predominant symptom was dysphagia, present in all patients, followed by regurgitation (16.6%), pyrosis (heartburn) (16.6%) and cough (8.3%). In all cases, the diagnostic method used was barium swallow. The median diverticular size recorded was 32.5 mm, IQR: 20 and range: 10−50 mm.

All the patients showed initial clinical improvement after the procedure. Three patients (25%) had a clinical recurrence during follow-up, two of which underwent the same procedure again (both with technical success), with one remaining outstanding.

A total of 14 surgeries were performed (Table 2), 13 of which were deemed technically successful (92.8%). In the remaining case, an incomplete septotomy was conducted as the technique had to be interrupted due to the difficulty arising from inadequate positioning of the diverticuloscope, which also caused mild bleeding that required treatment with injected adrenaline. This same case continued to experience dysphagia after two months (clinical recurrence), requiring surgery after six months, this time with technical success.

Procedure-related parameters.

| Total, n | 14 |

| Technical success, n (%) | 13 (92.8%) |

| Intra-procedural complications, n (%) | |

| Bleeding | 1 (7.1%) |

| Post-procedural complications, n (%) | |

| Odynophagia | 4 (28.5) |

| Nausea | 1 (7.1%) |

| Fever | 0 (0) |

| Bleeding | 0 (0) |

| Perforation | 0 (0) |

| Procedure duration, min | 30.7 |

| Number of haemostatic clips used, mean | 1.9 |

| Mean post-procedural hospital stay, h | 34.2 |

H, hours; min, minutes; n, number.

It was the only significant intra-procedural complication recorded. Some minor post-procedural complications were also observed: odynophagia in four cases (28.5%) and nausea in one (7.1%). No patient had fever or major complications such as delayed bleeding or perforation.

Three procedures (21.4%) were performed under deep sedation and 11 with general anaesthesia and orotracheal intubation. The mean procedure duration was 30.7 min. Haemostatic clips were used as prophylaxis for delayed bleeding and/or perforation in all patients, with a mean of 1.9 clips per procedure (range: 1−3).

Mean hospital stay was 46.2 h in total, with a mean post-operative stay of 34.2 h (each patient was admitted 12 h before the procedure). Patients were discharged 24 h after the procedure in 11 cases (78.5%), while discharge was delayed for up to 72 h in three procedures: in one case the beginning of oral tolerance was delayed due to pain and in the other two cases for reasons not related to the intervention or the patient's symptoms.

Literature reviewThe literature review yielded 13 results. Five results were discounted: one because it was a review, one because it was a letter to the editor and three because they were studies based on other techniques. Eight publications between 2013 and 2020 were ultimately included. The variables collected are expressed in Table 3.13–20 Six of them were retrospective studies,14–20 one a clinical case16 and another one a case series.13

Literature review. Studies included on endoscopic diverticulotomy by SB-Knife®.

| Author, year and country of publication | Sample size (female), n | Age, mean ± SD or median (IQR, range) | Mean diverticulum size (range) or median (IQR, range), mm | Type of technique | Devices | Clin. resp., n (%) | Complications, n (%) | Recurrence, n (%) | No. of procedures/patient | Use of clips | Use of ATB | Procedure duration, mean ± SD or median (IQR, range), min | Anaesthesia | Mean post-procedural hospital stay, h | Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ramchandani and Nageshwar Reddy, 2013, India13 | 3 (1) | M 71 (70−87) | NR | Single incision | 2 CAP and 1 DES | 3 (100) | 1 (33) intra-procedural bleeding | NR | 1 | 1 patient, 1 clip | NR | 10.6 (10−12) | General anaesthesia | NR | Case series |

| Battaglia et al., 2015, Italy14 | 31 (6) | Mn 71 (11, 52−85) | Mn 30 (20, 10−80) | Double incision and removal with loop | DES | 26 (83.9) | 1 (3.2) delayed bleeding | 5 (16.1) | 1.09 | All; 2−3 clips | No | 14 (4, 11−23) | Deep sedation, propofol | 48 | Retrospective study |

| Goelder et al., 2016, Germany15 | 52 (18) | M 71 (42−86) | M 30 (10−50) | Single incision | DES | 47 (90.4) | 1 (1.9) perforation; 5 (9.6) intra-procedural bleeding | 6 (11.5) | 1.11 | 10 patients; 1−3 clips | Yes | NR | Deep sedation, propofol | NR | Retrospective study |

| Martin-Guerrero et al., 2017, Spain16 | 1 (0) | 72 | 80 | Single incision | DES | 1 (100) | 0 | NR | 2 | All; 3 clips | NR | 30 | Deep sedation, propofol and midazolam | NR | Case report |

| Gölder et al., 2018, Germany17 | 16 (6) | Mn 70 (54−85) | Mn 20 (5−40) | Double incision and removal with loop | DES | 14 (87.5) | 0 | 2 (12.5) | 1.12 | 3 patients; 1−4 clips | Yes | 28 (20−47) | Deep sedation, propofol and midazolam | NR | Retrospective study |

| García-Fernandez et al., 2019, Spain18 | 15 (5) | M 71 ± 11 | M 30 ± 20 (15−70) | Single incision | DES | NR | 1 (6.2) subcutaneous emphysema; 2 (12.4) low-grade fever; 1 (6.2) delayed bleeding | 0 | 1 | All, 2 clips | Yes | 37 | NR | 30 | Retrospective study |

| Gomez-Outomuro et al., 2020, Spain19 | 16 (6) | Mn 78 (11, 47−93) | Mn 20 (13.7, 10−40) | Single incision | DES | 14 (87.5) | 2 (12.5) pain; 3 (18.7) fever; perforation 1 (6.3) | 2 (12.5) | 1.12 | No | No | NR | Deep sedation, Propofol | 30 | Retrospective study |

| Ishaq et al., 2020, United Kingdom20 | 65 (39) | M 74 ± 12 | Mn 24 (17−30) | Single incision | 63 CAP and 2 DES | 49 (75.4) | 2 (3.1) hypoxia, 2 (3.1) intra-procedural bleeding | 16 (24.6) | 1.4 | All, 1−3 clips | NR | 20 (16−25) | Deep sedation, propofol and remifentanil | <24 | Retrospective study |

ATB, antibiotic; CAP, cap; Clin. Resp., clinical response; DES, diverticuloscope; h, hours; IQR, interquartile range (only expressed if available); M, mean; min, minutes; Mn, median; No., number; NR, not recorded; SD, standard deviation.

Sample size varied, depending on the series, between 1 and 65, with a total of 199 patients (60.3% male and 40.7% female). Age was expressed in four studies as the mean and in four as the median, and was above 70 in all publications (between 42 and 93). The main symptom in all the series was dysphagia, the exact number of patients was not specified in 2/8 studies, and the overall mean of all the samples was 98.2% of the patients. The second most common symptom was regurgitation, reflected only in 6/8 studies, with a mean of 70.5%. Respiratory symptoms are reported in 5/8 studies, with an average of 39.8%. The size of the diverticulum is stated in 7/8 series, with the mean or the median values varying between 20 mm and 80 mm. Diagnosis was performed by the barium swallow test in 37.5% of the studies and by videofluoroscopy in 12.5%, whereas the method was not specified in 50% of the studies.

In 5/8 studies, the SB-Knife™ Jr type (3.5 mm) device was used in all of the procedures, as well as in 56/58 of the series by Goelder et al.15 (a total of 163 procedures). In the study by Battaglia et al.,14 the SB-Knife™ short type (6 mm) was used, while in 2/58 of the series by Goelder et al.,15 the standard type (7 mm) was used, as well as in 1/3 patients of the series by Ramchandani and Nageshwar Reddy,13 whereas the type was not stated in the remaining patients of this series.

Six of eight series used the diverticuloscope as a complementary accessory in all patients, whereas the other two series used the following: Ramchandani and Nageshwar Reddy,13 a cap in 2/3 and diverticuloscope in 1/3 of the patients; and Ishaq et al.,20 a cap and 63/65 and diverticuloscope in 2/65.

In all the studies, the single incision technique in the diverticular septum was used, except for two studies14,17 in which a parallel double incision was performed with subsequent resection of the muscle fibres and the mucosa with a polypectomy loop.

Haemostatic clips were placed prophylactically in all patients in half of the series, they were not used in one study19 and in the rest it was left up to the discretion of the endoscopist. Mean procedure duration ranges from 10.6 min to 37 min (overall mean: 23.2 min) and is not stated in two publications.

Clinical response ranges from 75.4% to 100%. The most frequently recorded complication is mild intraprocedural bleeding in eight cases (4%). Recurrence varies between 11.5% and 24.6% (mean: 12.8%) and is not recorded in two studies.

In one series, the technique was performed with general anaesthesia,13 whereas deep sedation was used in the other seven. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy was administered in three series,15,17,18 not given in two studies and not specified in the rest. Mean hospital stay is recorded in half of the studies and varies between less than 24 h and up to 48 h, with a mean of 39 h.

DiscussionThere are several ZD treatment techniques, which may be classified into three groups: open transcervical surgical approach, rigid endoscopic treatment and flexible endoscopic treatment. Due to the underlying pathophysiology of ZD, the key to treatment efficacy lies in the myotomy of the cricopharyngeal muscle, which is why it is included in all the options.21

Since the first surgery described in 1886 by Wheeler, treatment for ZD has evolved substantially, particularly in the last two decades. Treatment with rigid endoscope was first described by Mosher22 in 1917, and the first minimally invasive surgery with flexible endoscope in 1995 by Ishioka et al.8 and by Mulder et al.23 Since then, numerous techniques have been developed, using different cutting devices and accessories with a view to increasing safety and treatment success, which have now displaced conventional surgical techniques. The first device used for flexible ED was the Needle-Knife™ (Wilson Cook Bloomington, In, USA) papillotome, an inexpensive, accessible method, albeit with a considerable risk of perforation derived from the difficulty involved in controlling the septotomy, which requires a ventrodorsal movement, making it more complicated to gauge cutting depth. Other accessible low-cost systems are argon plasma coagulation and CO2 laser, with the related disadvantage of increased complications (mainly emphysema and bleeding). The Hook-Knife™ (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan) device was designed initially for submucosal endoscopic dissection and was used for ED with good results, offering the theoretical advantage of reducing the percentage of perforations thanks to its hook shape.24

Other instruments used are bipolar sealers-cutters such as Enseal® or Harmonic® scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) and Ligasure® (LS1500, Covidien; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Although the techniques performed with these devices are safe and yield a low rate of recurrence, as shown by the literature,25 we consider that since they are not inserted through the endoscope's working channel but rather parallel to it, they have the disadvantage versus other cutters of offering a poorer view of the diverticular septum during septotomy, which may hamper technical success.18

Recently, the SB-Knife™ (Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Tokyo, Japan) device was developed, a scissors-like knife with both blades fully isolated. Its design ensures good grip and a precise cut of the muscle fibres of the diverticular septum, pulling these fibres towards the endoscope, thereby avoiding possible damage to deeper layers and potential perforation. It also provides 360° rotation, thus increasing incision precision.14,20

In recent years, other novel techniques have been developed, such as the computer-assisted flexible endoscopy system (Flex System), new devices for septotomy (Clutch Cutter-Knife™, Microcutter XCHANGE, BELA) and endoscopic septotomy by means of submucosal tunnelling. The latter, also known as Zenker’s peroral endoscopic myotomy (Z-POEM), is a variant of the technique developed for the treatment of achalasia, consisting of submucosal tunnelling prior to septotomy. It differs from the latter in the greater complexity derived from the anatomical characteristics in the UOS versus the LOS (narrower location and absence of external muscle layer), which may theoretically increase adverse events. In our opinion, this procedure involves a steeper learning curve for the advanced endoscopist compared to endoscopic approaches such as septotomy with SB-Knife™, making it less accessible. In the same way, the efficacy and safety of these emerging techniques and devices have not yet been demonstrated in studies with any statistical robustness.20

De la Morena Madrigal et al.26 present the largest record in our setting of ZD ED, spanning 13 years and a total number of 64 patients treated with Needle-Knife™ devices. The study found symptom recurrence of 19% and 24 patients with complications (one perforation, one dehiscence and 21 cases of intraoperative bleeding). The results of our study are superimposable to this one in terms of epidemiological data, although they differ in terms of the lower number of complications and higher symptom recurrence rate. The same is true when comparing our data to the other studies analysed in the literature review (Table 3), all of them with SB-Knife™. We believe that the lower clinical success rate observed in our series compared to other studies with the same or other endoscopic techniques could be related to the performance of septotomies that are more conservative than would be desirable. This avoids the theoretical risk of major complications, although, since too much diverticular septum is left intact, this would favour symptom recurrence.

There is a variant in the conventional septotomy with SB-Knife™, which consists of performing a double incision on the diverticular septum with a subsequent excision with polypectomy loop of the central fibres of the septum. Several studies have shown a good safety profile associated with this technique, with low recurrence rates.14,17 The Pang et al. group27 called this technique myectomy and compared it, in a retrospective study, to myotomy or standard septotomy (both groups performed with Needle-Knife™ or Hook-Knife™). They found a lower recurrence rate in the myectomy cohort, without any other significant differences.

With regard to the use of accessory devices, there are different ways to isolate the diverticular septum. There are studies that support the use of the diverticuloscope versus the cap as they demonstrate greater efficacy, shorter procedure duration and fewer complications (0% vs 18% perforations).28 In contrast, a recent French study29 with 77 patients (60 diverticuloscope vs 17 cap) found no statistically significant differences between the two devices. The clinical practice guideline of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) suggests, with a low level of evidence, that the decision on whether or not to use diverticuloscope should be taken by the endoscopist at their own discretion.30 In our experience, we consider that the diverticuloscope affords safety to the technique by stabilising the work field, protecting the oesophageal and diverticular wall, permitting an extensive controlled septotomy and therefore theoretically reducing the rate of recurrence.

Due to the rapid development of the endoscopic treatment of ZD, until recently there were no specific recommendations on the use of antibiotic prophylaxis. A recent Spanish study19 in which antibiotic prophylaxis was not performed identified 18% of patients with postoperative fever. In contrast, an Italian study14 found no infectious complications despite antibiotic prophylaxis not being administered. Recently, the ESGE clinical practice guideline recommended not using routine antibiotic prophylaxis in this procedure, albeit with a low level of evidence.30 The procedures in our study were performed prior to the publication of this guideline and therefore prophylaxis was administered to all patients with no evidence of infectious complications found after the procedures performed. Further studies will probably be necessary in the future with regard to this recommendation.

In our study, following the endoscopic septotomy, between one and three haemostatic clips were placed in all the surgical patients. The objective of this practice is to prevent postoperative bleeding and dissection of the oesophageal mucosa, with the ensuing perforation. In the literature review performed, we found four publications in which prophylactic clips were placed,14,16,18,20 identifying two delayed haemorrhages and one subcutaneous emphysema out of a total of 112 patients. In a Spanish study from the same review, this practice was not performed on any patients and one perforation was identified out of 16 procedures.19 As with the use of the diverticuloscope, the ESGE concludes that the decision on the use of clips should be at the discretion of the endoscopist and in accordance with clinical need.30 In our study, we found no case of perforation or delayed bleeding, whereby, according to experience, we believe that it could be a beneficial practice, although comparative studies are required.

We consider that our study has several limitations, the main one being its retrospective descriptive design and small sample size. Moreover, no standardised pre-and post-procedural dysphagia scale was used, meaning the clinical response to the technique cannot be objectively defined.

In our opinion, and in light of our experience, ED by SB-Knife™ is a safe, effective and reproducible technique; it could be a better alternative than surgery for the majority of patients with ZD in view of their baseline characteristics. We think that future studies should clarify the pros and cons of this technique compared to others and suggest that a variation in the technique with excision with polypectomy loop could be an option for avoiding recurrence.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Toro-Ortiz JP, Fernández-García F, Pinazo-Bandera J, Alcaín Martínez GJ, Lavín Castejón I, Septotomía endoscópica del divertículo de Zenker mediante Stag-Beetle-KnifeTM: estudio observacional descriptivo y revisión de la literatura, Gas-troenterología y Hepatología, Gastroenterología y Hepatología. 2022;96:432–439.