Esophageal ulcers constitute a relatively common cause of dysphagia and odynophagia. Gastroesophageal reflux and consumption of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) account for most of the cases. Malignancies and infectious esophagitis due to Candida or herpesviruses may also present as dysphagia.1 The endoscopic appearance of the ulcer is often useful to differentiate between these conditions, with further confirmation by histopathological examination. We report herein a malignant-appearing esophageal ulcer due to paraesophageal tuberculous lymphadenitis in an immunocompetent patient that resolved after anti-tuberculosis therapy. Although lymph node tuberculosis is among the most common extrapulmonary sites of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, esophageal involvement presenting as esophageal ulcer is rare, with only a few cases previously reported in the literature.2–5

A 40-year-old Bolivian male presented to the Emergency Department complaining of upper abdominal pain accompanied by progressive dysphagia and odynophagia over the previous month. Past medical history was remarkable for non-complicated peptic ulcer ten years ago. He denied both alcohol and tobacco consumption or illicit drugs use. The patient reported moderate epigastric burning feeling with further development of non-colicky pain as well as progressive dysphagia, first to solids and later to liquids. The patient eventually suffered from severe odynophagia, for which he had taken occasional acetaminophen without symptomatic relief. Review of systems was unremarkable for nausea, vomiting or halitosis. He had not experienced weight loss, decrease in appetite or fever. On physical examination the patient appeared well-nourished and hydrated. Oral cavity examination excluded the presence of exudates. No cervical lymphadenopathy was noted and cardiopulmonary examination was unremarkable. Laboratory testing showed normal complete blood count and renal and hepatic function tests. Chest X-ray revealed no abnormalities. Further testing for human immunodeficiency and hepatitis B and C viruses was negative.

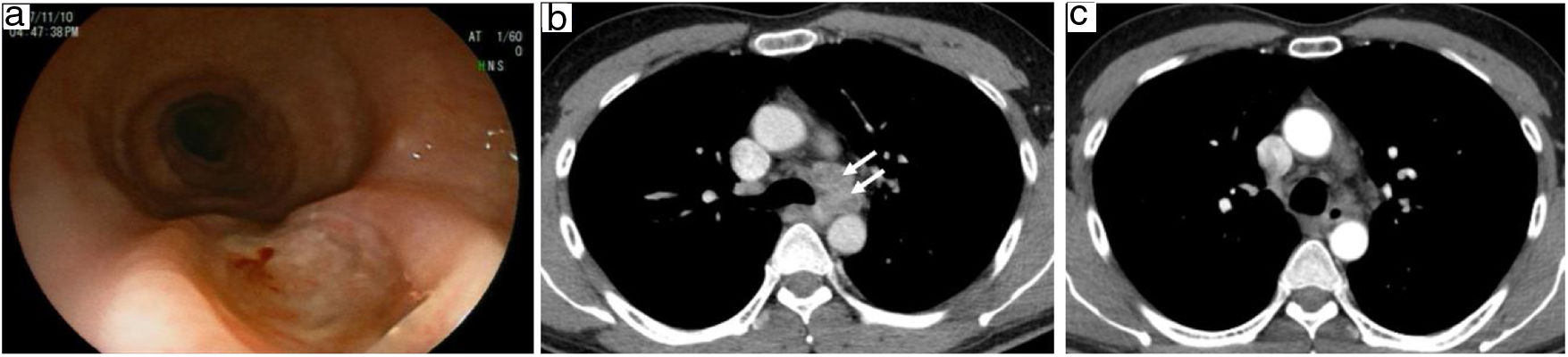

As part of the diagnostic approach to progressive dysphagia, the patient underwent upper endoscopic examination which revealed a 1cm size ulcer in the middle third (Fig. 1a). Tissue samples were obtained. A contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CT) scan revealed the presence of multiple enlarged lymph nodes affecting the left paratracheal (Fig. 1b), left supraclavicular and right paratracheal regions. These nodes caused extrinsic compression of the esophageal structures with subsequent stenosis. Neither parenchymal infiltration within pulmonary or intraabdominal structures nor pleural effusion was noted. Histopathologic findings were consistent with the presence of scattered epithelioid granulomas showing central necrosis surrounded by abundant granulation tissue. A tuberculin skin test (TST) was positive (20mm) and a new endoscopic examination was performed for further microbiological studies. The aforementioned lesion was shown to have progressed, measuring approximately 1.5cm. The patient had no sputum production, and the PCR assay for M. tuberculosis complex (Xpert MTB/RIF, Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) in the gastric aspirate was negative. Despite both acid-fast bacilli smear and specific mycobacterial cultures were negative, a diagnosis of tuberculous lymphadenitis was presumptively made given the histological and radiological findings in the presence of a clearly positive TST and compatible epidemiological history. Patient was started on antituberculosis therapy. Symptoms gradually improved over the next weeks. After completing the two-month intensive phase of therapy with four drugs, a follow-up endoscopic assessment showed complete remission of the lesion, whereas a significant reduction in lymph nodes sizes was observed in the CT scan (Fig. 1c). The two-drug continuation phase (isoniazid and rifampicin) was uneventfully maintained for four further months, with complete symptom resolution.

(a) Endoscopic examination revealing a malignant-appearing ulcerative lesion in the mid-thoracic esophagus; (b) CT scan at admission, with enlarged lymph nodes (33mm×22mm×28mm) in left paratracheal region compressing the esophageal lumen; (c) CT scan after two months of four-drug anti-tuberculous therapy, showing marked reduction in lymph node sizes and recanalization of the esophageal occlusion.

Tuberculosis is a rare cause of dysphagia that should be considered in patients from endemic regions with uncertain esophageal lesions.2,3 In addition, dysphagia may also result from the extrinsic compression of the esophagus by mediastinal or neck lymph nodes (as occurred in the present case) or due to the development of tracheoesophageal fistula. Esophageal ulcer is the most common endoscopic finding, whose appearance is often suggestive of malignancy.4 However, as mentioned above, other endoscopic findings reported in patients with esophageal tuberculosis include esophageal stenosis, tracheoesophageal fistula or exophytic mass, widening the differential. Therefore, histological and microbiological examination plays a crucial role. Culture positivity for M. tuberculosis on tissue samples is uncommon, and the diagnosis is only established by demonstrating clinical, radiological and endoscopic response to anti-tuberculosis treatment, as exemplified by our experience.2 In the absence of culture confirmation, endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of the lymph node represents a valuable diagnostic tool, particularly taking into account the need of ruling out alternative Follow-up endoscopic assessment is mandatory in order to confirm endoscopic healing of lesions, since malignancy and esophageal tuberculosis may coexist.4 Of note, a case of esophageal tuberculosis diagnosed after an esophagectomy performed due to esophageal stricture with histologic features of high-grade dysplasia has been described, stressing the need of considering tuberculosis in the differential diagnosis.5 In conclusion, the possibility of esophageal ulcer caused by paraesophageal tuberculous lymphadenitis with mucosal involvement should be kept in mind in patients from high-prevalence countries and evidence of esophageal granulomas, even if M. tuberculosis is not isolated in tissue cultures. Anti-tuberculosis therapy is usually curative in this uncommon condition.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.