Achieving adequate bowel cleansing is of utmost importance for the efficiency of colon capsule endoscopy (CCE). However, information about predictive factors is lacking. The aim of this study was to assess the predictive factors of poor bowel cleansing in the CCE setting.

MethodsIn this observational study, 126 patients who underwent CCE at two tertiary care hospitals were included between June 2017 and January 2020. Participants prepared for bowel cleansing with a 1-day clear liquid diet, a 4-L split-dose polyethylene glycol regimen and boosters with sodium phosphate, sodium amidotrizoate and meglumine amidotrizoate. Domperidone tablets and bisacodyl suppositories were administered when needed. Overall and per-segment bowel cleansing was evaluated using a CCE cleansing score. Simple and multiple logistic regression analysis were carried out to assess poor bowel cleansing and excretion rate predictors.

ResultsOverall bowel cleansing was optimal in 53 patients (50.5%). Optimal per-segment bowel cleansing was achieved as follows: cecum (86 patients; 74.8%), transverse colon (91 patients; 81.3%), distal colon (81 patients; 75%) and rectum (64 patients; 66.7%). In the univariate analysis, elderly (OR, 1.03; 95% CI (1.01–1.076)) and constipation (OR, 3.82; 95% CI (1.50–9.71)) were associated with poor bowel cleansing. In the logistic regression analysis, constipation (OR, 3.77; 95% CI (1.43–10.0)) was associated with poor bowel cleansing. No variables were significantly associated with the CCE device excretion rate.

ConclusionOur results suggest that constipation is the most powerful predictor of poor bowel cleansing in the CCE setting. Tailored cleansing protocols should be recommended for these patients.

Antecedentes y objetivos Lograr una limpieza intestinal adecuada es de gran importancia para la eficiencia de la cápsula endoscópica de colon (CEC). Se carece de información sobre factores predictivos. El objetivo fue evaluar los factores predictivos de la limpieza colónica deficiente en pacientes con CEC.

MétodosCiento veintiséis pacientes fueron sometidos a CEC en dos hospitales de tercer nivel entre junio de 2017 y enero de 2020. La preparación consistió en un día de dieta líquida, y 4 l de polietilenglicol (dosis fraccionada), fosfato sódico, amidotrizoato de sodio y meglumina amidotrizoato. Ocasionalmente se administró domperidona y supositorios de bisacodilo. Se evaluó limpieza total y por segmentos. Se realizó un análisis de regresión logística simple y múltiple para evaluar factores de limpieza deficiente y de excreción de la CEC.

ResultadosLa limpieza intestinal fue óptima en 53 pacientes (50,5%). Por segmentos fue: ciego y ascendente (86 pacientes; 74,8%), transverso (91 pacientes; 81,3%), distal (81 pacientes; el 75%) y recto (64 pacientes; 66,7%). En la regresión simple, la edad avanzada (OR, 1,03, IC 95% [1,01-1,076]) y el estreñimiento (OR, 3,82; IC 95% [1,50-9,71]) se asociaron con una limpieza deficiente. El estreñimiento (OR, 3,77; IC del 95% [1,43-10,0]) fue el único factor asociado de forma independiente. Ninguna variable se asoció a la tasa de excreción de la CEC.

ConclusiónNuestros resultados sugieren que el estreñimiento es el factor más potente de la limpieza deficiente colónica en el estudio endoscópico con CEC. Protocolos de limpieza adaptados se deben recomendar en estos pacientes.

Colonoscopy reduces the incidence and mortality rates of colorectal cancer (CRC) in a screening setting and is the gold standard for examination of the colon.1,2 However, it is far from being an ideal technique and has several limitations. First, it is an invasive procedure with potentially life-threatening complications; second, it is not infallible, missing up to 12% of advanced colorectal neoplasms (ACNs: CRC or advanced adenoma)3; and third, it is not always well accepted by the patients. Colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) is a minimally invasive test introduced in 2006.4 It can be performed on an outpatient basis and does not require sedation, which could increase adherence. Furthermore, its sensitivity in identifying ACN is high, detecting up to 100% of CRCs and 92% of advanced adenomas.5–7 The European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) specifically recommended this test for patients in whom colonoscopy was incomplete due to technical factors or safety concerns, as well as an alternative in subjects who have contraindications or refuse to undergo a conventional colonoscopy.8 For CCE, colon cleansing is essential to achieve a high-quality examination. In addition, the inherent characteristics of CCE, such as the inability to distend the large bowel wall, aspirate fluid and debris, and wash,9 render the need for excellent bowel cleansing more critical when this device is used. In the CCE setting, the rate of inadequate preparation ranges from 12% to 34% according to different studies.10

Although there is a vast amount of information available about predictive factors of poor bowel cleansing in conventional colonoscopy (CC),11,12 currently, there is a lack of studies evaluating the independent predictors of poor colon preparation in patients undergoing CCE. Another important issue is the completion of the CCE examination. In this regard, it has been established that CCE would not be an efficient strategy if an examination completion rate of at least 75% is not achieved.13

Therefore, the primary aim of the present study was to assess the predictive factors for colon cleansing quality in the CCE setting, and the secondary aim was to analyze the predictors for large bowel examination completion.

MethodsPatientsThis cross-sectional study was conducted at the Open Access Endoscopy Units of two tertiary referral hospitals (hospital 1: University Hospital of the Canary Islands, Tenerife; hospital 2: Hospital Clínic i Provincial, Barcelona) that overall provide health care to 940,000 inhabitants. Between June 2017 and January 2020, all patients over 18 years of age who were referred for first-time CCE examination were considered for inclusion in the study. If CCE was requested due to incomplete conventional colonoscopy, an India ink tattoo was created at two points at the level of the most proximal colonic margin reached. In this case, colonoscopy was attempted by two endoscopists before the patient was considered for inclusion in the study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: mechanical or functional intestinal obstruction; megacolon; poorly controlled hypertension (systolic blood pressure>180mmHg, diastolic blood pressure>100mmHg); congestive heart failure; acute liver failure; end-stage renal failure (dialysis or predialysis); pregnancy; lactation; dementia with difficulty in complying with the preparation regimen; dysphagia; previous inclusion in the study; previous colon surgery; history of poor preparation for CCE; risk of capsule retention (i.e., Crohn's disease or radiation enteritis); allergy to any component of the bowel preparation regimen; and refusal to sign the informed consent form.

The protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of Hospital Universitario de Canarias and Hospital Clínic i Provincial, Barcelona (CHUC_2016_07).

Procedures carried out before CCEAn appointment at the outpatient clinic was scheduled for all patients for whom a CCE examination was requested, regardless of the indication. A research physician (Z.A.G., A.Z.G.G., B.G.S.) obtained written informed consent and explained the purpose of the study to the included patients. A questionnaire including the following demographics and predictors of inadequate bowel cleansing reported for conventional colonoscopy was administered (Appendix 1): age; sex; body mass index (BMI); comorbidities (diabetes with medical treatment, cirrhosis, stroke, or chronic kidney disease defined as renal glomerular filtration<60mL/min); medications (tricyclic antidepressants, opioids and calcium antagonists); indication for the examination; constipation (<3 bowel movements/week and at least one of the following: straining, hard stools defined as Bristol score 1 or 2, and incomplete evacuation)14; educational level (higher or lower than high school); personal history of colon polyps or CRC; family history of CRC; and history of abdominal or pelvic surgery.

Finally, the participants received a pedometer to count the number of steps from the beginning of the bowel preparation until the excretion of the CCE device or the end of the battery life.

Bowel preparation and CCE administrationA second-generation CCE device and Rapid™ Reader Software v. 8.3 (Given Imaging, Ltd., Yoqneam, Israel) were used in this study.

All participants received oral and written instructions about intestinal preparation, as follows8,15:

- -

Day before CCE: a clear liquid diet and 2L of polyethylene glycol (PEG) in the evening (7–9 p.m.)

- -

Day of the procedure:

- -

2L of PEG in the early morning (7–8a.m.)

- -

Ingestion of the CCE device at the hospital at 9a.m.

- -

10mg of domperidone was administered if the CCE device was delayed in the stomach for longer than 1h

- -

First booster (upon small bowel detection): 40mL of sodium phosphate (NaP) and 0.5L of water with 50mL of sodium amidotrizoate and meglumine amidotrizoate (Gastrografin™)

- -

Second booster: 25mL of NaP and 0.5L of water with 25mL of Gastrografin™ administered 3h after the first booster if the CCE device was not excreted

- -

10mg of bisacodyl suppository 2h after the second booster if the CCE device was not excreted

- -

A survey including tolerance (vomiting and willingness to undergo the same bowel preparation regimen in the future) and compliance with instructions was given to the participants the day of the examination. The number of steps was also registered.

CCE readingThe reading of the exploration was carried out by 5 endoscopists (B.G.S., Z.A.G., L.R., O.A.F., A.G.) experienced in either the small bowel capsule or CCE examination (>150 capsule endoscopies and >2000 conventional colonoscopies). CE recordings were recommended to be read at a maximum speed of 10 frames per second in the single-view mode. Images of the cecum, hepatic and splenic flexures and the last captured image were recorded. Cleansing quality was assessed according to the modification of the Leighton et al. CCE cleansing score15,16 (supplementary Table 1). Four segments were rated by the readers: the proximal colon (cecum and ascending colon); transverse colon; distal colon (descending colon and sigmoid); and rectum. Each segment was rated from 1 (no preparation) to 4 (excellent preparation). The maximum and minimum overall score was 16 and 4, respectively.

In the case of a complete examination, patients with a minimum score of 3 points per segment were considered to have proper bowel cleansing. In the case of an incomplete examinations, if the score of 1 or more explored segments was <3 points, cleansing quality was considered inadequate. However, if the examination of the explored segments was adequate or the capsule did not reach the colon, the data were excluded from the analysis. The presence and location of the lesions found in the colon were registered in the CCE report. The polyp size estimation included in the Rapid Reader software was used to measure the polyps found.

The report also provided information about examination completion and whether the tattoo was identified during the examination.

In addition, to calculate interobserver agreement, the bowel preparation of 20 truncated videos (20s each) of the different segments of the colon, randomly selected from a video bank of one of the participating centers, was rated by the capsule readers.

OutcomesMain outcomeThe main outcome was the rate of adequate bowel cleansing assessed by the Leighton et al. classification.15,16 Independent predictors of cleansing quality were assessed.

Secondary outcomesThe secondary outcome was the rate of CCE completion, defined as CCE device expulsion and/or visualization of the hemorrhoidal plexus.

Statistical analysisThe results for continuous variables are expressed as the mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. The results of the simple logistic regression analysis are expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed using bowel quality (defined as a score≥3 in each segment) as the dependent variable and variables with a P value≤0.15 in the univariate analysis. The results are expressed as the OR and 95% CI. With the statistical objective of including a minimum of 6 covariates in the multiple regression model, 126 patients were included in the study, 105 of whom were included for the primary aim.

A simple logistic regression analysis was also performed using examination completion (defined as CCE device excretion or visualization of the hemorrhoidal plexus) as the dependent variable. Variables with a P value≤0.15 in the univariate analysis were included in the multiple logistic regression analysis. The results are expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. The interrater reliability was calculated by Cohen's kappa (κ). The coefficients were interpreted according to Landis’ classification.17

Data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences v. 25.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

ResultsThe endoscopists showed a moderate interobserver correlation when bowel cleansing was categorized from 1 to 4 points (kappa=0.60). However, in most cases, the discordances were between 1 and 2 points (poor and fair) or between 3 and 4 points (good and excellent). Indeed, when the analysis was performed comparing inadequate bowel preparation (poor and fair) vs. adequate bowel preparation (good and excellent), the correlation was excellent (kappa=0.84).

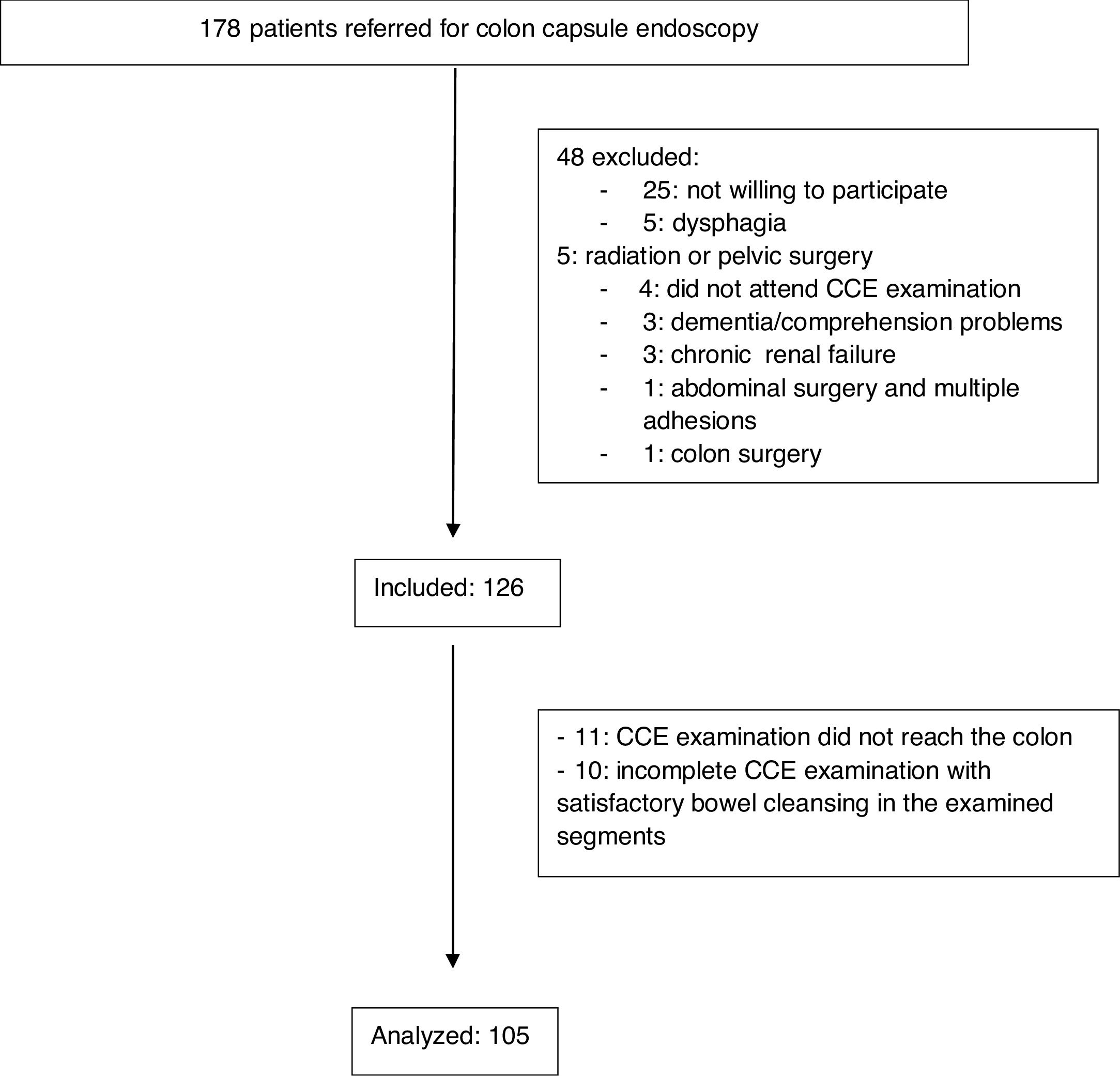

Overall, 178 patients were referred for CCE. Of them, 48 were excluded for different reasons (Fig. 1). Four patients met the inclusion criteria but did not attend the examination. Finally, 126 patients were included. Of the whole sample, 92 (73%) were women, and 34 (27%) were men. The median age was 67.5 years (range, 24–85 years). The indications for CCE are shown in Table 1. In most cases, the indication was incomplete conventional colonoscopy (n=119, 94.4%), followed by refusal to undergo conventional colonoscopy (n=6, 4.8%) and anesthesia risks (n=1, 0.8%). Approximately one-fifth of the participants had a significant comorbidity (n=27, 21.4%), with diabetes mellitus (n=22, 17.5%) and liver cirrhosis (n=3, 2.4%) being the most common. Constipation was reported by 38 patients (30.2%), while 19 (15.1) were being treated with opioids, calcium antagonists or antidepressants. Overall, 10 patients (7.9%) were polymedicated. More than one-third of participants had a personal history of abdominal or pelvic surgery (n=44, 34.9%).

Regarding the preparation tolerance survey, 124 (98.4%) participants completed more than 75% of the bowel preparation regimen, only 7 (5.6%) had vomiting, and 97 (77%) agreed to complete the same preparation regimen in the future. There was no case of CCE device retention.

Tattooing was performed during conventional colonoscopy in 105 participants, accounting for 88.2% of the incomplete conventional colonoscopies.

Bowel cleansing and CCE device expulsionThe CCE device was excreted during the life of the battery in 96 (76.2%) participants. The median colon transit time was 154min (range, 71–276min).

Of the 126 patients meeting the inclusion criteria, the CCE device did not reach the colon in 11 participants (8.7%), and in the other 10 patients (7.9%), the study was incomplete, but bowel preparation in the examined segments was satisfactory. Overall, 105 patients were included in the univariate analysis and multiple logistic regression analysis. Bowel cleansing was considered adequate in 53 patients (50.5%: 50% in hospital 1 and 51.9% in hospital 2, P=0.87), in 59 patients (53.2%) if the tattoo was seen and only the segments proximal to the tattoo were evaluated and in 53 patients (55.2%) with complete examinations. Regarding the cleansing quality per segment, the cleansing quality was adequate in the cecum and ascending colon in 86 patients (86/115, 74.8%), the transverse colon in 91 patients (91/112, 81.3%), the distal colon in 81 patients (85/108, 75%) and the rectum in 64 patients (64/96, 66.7%).

Polyps were found in 51 patients (53.1%) with a complete examination, diminutive polyps were found in 26 (27.1%), and in one patient, CRC was diagnosed. There were no significant differences in the detection rate of polyps between patients with adequate and poor bowel preparation (n=27, 59.9% vs. n=24, 55.8%, respectively, P=0.634). No significant difference was found in the rate of diminutive polyp detection (n=15, 28.3% vs. n=11, 25.6%, respectively, P=0.765).

Predictive factors of inadequate bowel cleansing and CCE device expulsionIn the simple logistic regression analysis, age and constipation were the only variables associated with poor bowel cleansing (Table 2). However, since the use of tricyclic antidepressants/opioids or calcium antagonists showed a nonsignificant trend (P=0.095), this variable was also included in the logistic regression analysis (Table 3). As shown, constipation (P=0.007) was the only variable independently associated with poor bowel cleansing.

Comparison of patients with and without risk factors for poor bowel cleansing on univariate analysis.

| Risk factor | Adequate bowel cleansing (n=53) | Poor bowel cleansing (n=52) | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 61.4±11.95 | 66.4±12.06 | 1.03 (1.01–1.076) | 0.041 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.7 (0.32–1.72) | 0.481 | ||

| Male | 14 (26.4) | 17 (32.7) | ||

| Female | 39 (73.6) | 35 (67.3) | ||

| BMI, kg/m2, (mean±SD) | 26.8±4.71 | 27.5±4.68 | 1.03 (1.89–1.12) | 0.47 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 1.63 (0.63–4.22) | 0.31 | ||

| Yes | 9 (17) | 13 (25) | ||

| No | 44 (83) | 39 (75) | ||

| Polymedication, n (%)a | 1.02 (0.28–3.76) | 0.98 | ||

| Yes | 5 (9.4) | 5 (9.6) | ||

| No | 48 (90.6) | 47 (90.4) | ||

| Medication, n (%)b | 2.58 (0.82–8) | 0.095 | ||

| Yes | 5 (9.4) | 11 (21.2) | ||

| No | 48 (90.6) | 41 (78.8) | ||

| Constipation, n (%) | 3.82 (1.5–9.71) | 0.004 | ||

| Yes | 8 (15.1) | 21 (40.4) | ||

| No | 45 (84.9) | 31 (59.6) | ||

| Personal history of adenoma, n (%) | 1.866 (0.624–5.587) | 0.259 | ||

| Yes | 6 (11.3) | 10 (19.2) | ||

| No | 47(88.7) | 42 (80.8) | ||

| Family history of CRC, n (%) | 1.16 (0.43–3.14) | 0.765 | ||

| Yes | 9 (17) | 10 (19.1) | ||

| No | 44 (83) | 42 (80.8) | ||

| Low educational level, n (%) | 1.551 (0.710–3.385) | 0.27 | ||

| Yes | 28 (52.8) | 33 (63.5) | ||

| No | 25 (47.2) | 19 (36.5) | ||

| Abdominal/pelvic surgery, n (%) | 1.58 (0.70–3.58) | 0.27 | ||

| Yes | 15 (28.3) | 20 (38.5) | ||

| No | 38 (71.7) | 32 (61.5) | ||

| Vomiting, n (%) | 2.12 (0.37–12.20) | 0.387 | ||

| Yes | 2 (3.8) | 4 (7.7) | ||

| No | 51 (96.2) | 48 (92.3) | ||

| Number of steps (mean±SD)c | 4352.1±2585.4 | 5764.4±3973.8 | Mean difference, 1412; 95% CI (−963–3788) | 0.24 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; CRC: colorectal cancer.

No variable was associated with CCE device excretion (Tables 4 and 5).

Comparison of patients with and without risk factors for CCE device expulsion on univariate analysis.

| Risk factor | CCE device expulsion (n=96) | CCE device retention (n=30) | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 63.02±12.019 | 68.07±13.508 | 1.04 (0.999–1.079) | 0.058 |

| Sex, n (%) | 1.286 (0.494–3.344) | 0.606 | ||

| Male | 27 (28.1) | 7 (23.3) | ||

| Female | 69 (71.9) | 23 (76.7) | ||

| BMI, kg/m2, (mean±SD) | 27.262±4.808 | 26.994±5.647 | 1.01 (0.931–1.098) | 0.797 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 1.12 (0.405–3.097) | 0.827 | ||

| Yes | 21 (21.9) | 16 (20.0) | ||

| No | 75 (78.1) | 24 (80.0) | ||

| Polymedication, n (%)a | 3 (0.364–24.703) | 0.285 | ||

| Yes | 9 (9.4) | 1 (3.3) | ||

| No | 87 (90.6) | 29 (96.7) | ||

| Medication, n (%)b | 0.854 (0.28–2.603) | 0.781 | ||

| Yes | 14 (14.6) | 5 (16.7) | ||

| No | 82 (85.6) | 25 (83.3) | ||

| Constipation, n (%) | 0.676 (0.284–1.606) | 0.374 | ||

| Yes | 27 (28.1) | 11 (36.7) | ||

| No | 69 (71.9) | 19 (63.3) | ||

| Personal history of adenoma, n (%) | 0.657 (0.203–2.123) | 0.48 | ||

| Yes | 6 (11.3) | 7 (16.3) | ||

| No | 47(88.7) | 36 (83.7) | ||

| Family history of CRC, n (%) | 0.895 (0.313–2.559) | 0.836 | ||

| Yes | 9 (17.0) | 8 (18.6) | ||

| No | 44 (83.0) | 35 (81.4) | ||

| Low educational level, n (%) | 0.732 (0.324–1.656) | 0.453 | ||

| Yes | 28 (52.8) | 26 (60.5) | ||

| No | 25 (47.2) | 17 (39.5) | ||

| Abdominal/pelvic surgery, n (%) | 0.519 (0.225–1.200) | 0.122 | ||

| Yes | 30 (31.3) | 14 (46.7) | ||

| No | 66 (68.8) | 16 (53.3) | ||

| Vomiting, n (%) | 0.769 (0.141–4.184) | 0.761 | ||

| Yes | 5 (5.2) | 2 (6.7) | ||

| No | 91 (94.8) | 28 (93.3) | ||

| Number of steps (mean±SD)c | 5209.7±3409.8 | 5195.7±4316.2 | Mean difference, 14.06; 95% CI (−2757–2729) | 0.99 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; CRC: colorectal cancer.

Adequate bowel cleansing is crucial to achieve the maximum efficiency of bowel examination techniques. Regarding CCE, the goal should be to achieve outstanding bowel cleansing given the limitations of this technique, mainly the inability to wash away debris, aspirate fluid and insufflate the colon lumen. In this regard, the knowledge of factors predicting inadequate bowel cleansing is of the utmost importance to tailor specific cleansing strategies for patients in whom cleaning is more difficult or to better choose the most suitable patients for this examination.

It is important to note that given the limitations of CCE, the predictive factors of poor bowel cleansing may not necessarily be the same as those for conventional colonoscopy.

In the present study, we found that constipation was a unique independent factor predicting poor bowel cleansing. In addition, advanced age and treatment with opioids, tricyclic antidepressants or calcium antagonists showed a nonsignificant association with poor bowel cleansing. These are well-known factors in conventional colonoscopy.18–21 Indeed, a recent large cross-sectional study found that constipation, comorbidities, previous abdominal/pelvic surgery and treatment with antidepressants were predictive factors of poor bowel cleansing before a conventional colonoscopy.12 There is no consensus on the most suitable bowel cleansing protocol for patients at risk of poor bowel preparation. By analogy to conventional colonoscopy, patients noncompliant with the cleansing instructions may benefit most from educational strategies, whereas in intolerant patients, the next step should be switching to a different bowel preparation regimen (i.e., one with less volume and/or better flavor).22 Since the main outcome of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of the cleansing protocol, intolerant and noncompliant patients were excluded (only 2 patients completed <75% of the bowel preparation regimen). Once intolerance and noncompliance with the bowel preparation regimen are excluded, enhanced bowel cleansing protocols should be the next step in patients with the aforementioned characteristics (especially constipation).22 Indeed, a randomized controlled trial carried out in patients with difficulty preparing for conventional colonoscopy showed higher cleansing rates using an enhanced bowel preparation protocol (4L of PEG plus 10mg of bisacodyl plus 3 days of a low-fiber diet) compared with a conventional low-volume preparation protocol (2L of PEG plus 1 day of a low-fiber diet).23 In this regard, there have been no comparative studies of enhanced bowel preparation protocols versus conventional preparation protocols in patients with risk factors for poor bowel cleansing in the setting of CCE.

In our study, the rate of adequate bowel cleansing was approximately 50% among examinations reaching the colon and 56% of complete examinations. It is important to note that our bowel cleansing results were similar at the two participating centers. The bowel cleansing quality reported in CCE has varied across studies, ranging between 42% and 88%13,24,25 and, in most cases, between 70% and 80%.7,15,24–28 We are aware that our cleansing rates are less than those in most other reports despite the use of a similar bowel preparation protocol7,25,28 and the addition of Gastrografin™, a hyperosmotic agent used in radiological imaging that promotes the secretion of fluid into the gastrointestinal lumen, causing diarrhea. A large study that combined Gastrografin™ and sodium phosphate as boosters found adequate rates of colon cleansing (83%) and CCE device excretion (98%).15

There are several potential explanations for the variations in CCE bowel cleansing quality among the abovementioned studies. First, different inclusion criteria (i.e., screening population)25,26 and exclusion criteria (i.e., patients with diabetes mellitus, constipation, or contraindications for CT colonography)15,24,27 might influence the rate of adequate bowel cleansing among studies. Second, another plausible explanation is the high percentage of patients with potential risk factors for poor bowel cleansing, such as constipation, comorbidities, medication or polymedication, and history of abdominal or pelvic surgery, accounting for up to 66.7% of the total sample.

Regarding CCE device excretion, we did not find any variable significantly associated with this outcome. The particular characteristics of CCE make these factors different from those associated with incomplete CC.

To our knowledge, there has only been one study aiming to assess predictive factors for CCE examination completion.28 This study included 64 patients, with an excretion rate of 81.3%. The authors analyzed predictive factors of CCE completion and completion within 4h. They found that a water intake ≥12mL/min during the battery life was the only independent predictive factor associated with CCE examination completion. The same factor along with a BMI≥25kg/m2 and constipation were found when the analysis was carried out within 4h. This study is undermined by the lack of a sample size calculation and the use of a quite different bowel preparation protocol compared with that in most CCE studies. Since it was not the main outcome of the current study, our results may be underpowered to detect predictive factors for CCE device excretion.

Our study has some strengths. It is the first study to evaluate predictors of poor bowel cleansing in the CCE setting. Additionally, a standardized cleansing protocol was used, similar to that recommended by the ESGE and other groups.8,15

However, we are aware of the limitations of our study. First, as previously mentioned, although our rate of adequate bowel cleansing is lower than in other studies, we believe that our results are closer to real clinical practice than those reported in other studies, since less strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were used, and there were no significant differences between the two participating centers. Second, the Leighton et al. scale has not yet been validated. However, it is the only published scale for bowel cleansing quality in CCE. In addition, the excellent interobserver agreement found among the 5 experienced endoscopists who participated in the present study demonstrates the reliability of our results. Currently, some researchers are undertaking efforts to develop computed-based technologies to increase the reproducibility of bowel cleansing assessments that might be available in the near future.29 Third, our results might be undermined by the sample size. We believe that the low prevalence of some variables in our cohort precluded us to detect statistically significant association with bowel cleansing.

In conclusion, the current study suggests that constipation is the most important limiting factor in achieving good bowel cleansing in patients undergoing CCE. Future randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm whether specific protocols may improve the bowel cleansing quality in these patients.

Authors’ contributionsConception and design: Antonio Z Gimeno García, Zaida Adrián, Laura Ramos

Analysis and interpretation of the data: Alejandro Jiménez, Antonio Z. Gimeno García

Drafting of the article: Antonio Giordano, David Nicolás

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: Cristina Carretero, Onofre Alarcón, Enrique Quintero. Manuel Hernández Guerra

Final approval of the article: Antonio Z. Gimeno García, Begoña González

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that all the participants signed an informed consent. The protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of Hospital Universitario de Canarias and Hospital Clínic i Provincial, Barcelona (CHUC_2016_07).

Role of the funding sourceThis research has not received specific aid from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Conflicts of interestNone.