Obesity is a multifactorial, chronic, progressive and recurrent disease considered a public health issue worldwide and an important determinant of disability and death. In Spain, its current prevalence in the adult population is about 24% and an estimated prevalence in 2035 of 37%. Obesity increases the probability of several diseases linked to higher mortality such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, arterial hypertension, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, several types of cancer, or obstructive sleep apnea. On the other hand, although the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is stabilizing in Western countries, its prevalence already exceeds 0.3%. Paralleling to general population, the current prevalence of obesity in adult patients with IBD is estimated at 15%–40%. Obesity in patients with IBD could entail, in addition to its already known impact on disability and mortality, a worse evolution of the IBD itself and a worse response to treatments. The aim of this document, performed in collaboration by four scientific societies involved in the clinical care of severe obesity and IBD, is to establish clear and concise recommendations on the therapeutic possibilities of severe or type III obesity in patients with IBD. The document establishes general recommendations on dietary, pharmacological, endoscopic, and surgical treatment of severe obesity in patients with IBD, as well as pre- and post-treatment evaluation.

La obesidad es una enfermedad multifactorial, crónica, progresiva y recidivante considerada un problema de salud pública a nivel mundial y un importante determinante de discapacidad y muerte. En España su prevalencia actual en población adulta se sitúa en el 24% y se estima su incremento hasta el 37% en 2035. La obesidad aumenta la probabilidad de diversas enfermedades vinculadas a una mayor mortalidad como diabetes, enfermedades cardiovasculares, hiperlipidemia, hipertensión arterial, enfermedad del hígado graso no alcohólico, varios tipos de cáncer o apnea obstructiva del sueño. Por otra parte, aunque la incidencia de enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) se está estabilizando en los países occidentales, su prevalencia supera ya el 0,3%. Paralelamente a lo que ocurre en la población general, la prevalencia actual de obesidad en pacientes adultos con EII se estima en el 15%–40%. La obesidad en pacientes con EII podría comportar, además de su impacto sobre la discapacidad y mortalidad ya conocido, una peor evolución de la EII y peor respuesta a los tratamientos. El objetivo del presente documento, elaborado en colaboración por cuatro sociedades científicas implicadas en la atención médica de la obesidad grave y la EII, es establecer unas recomendaciones claras y concisas sobre las posibilidades terapéuticas de la obesidad grave en pacientes con EII. En el documento se establecen recomendaciones generales sobre el tratamiento dietético, farmacológico, endoscópico y quirúrgico de la obesidad grave en pacientes con EII, así como la evaluación pre y post-tratamiento.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Obesity Federation (WOF) define obesity as a complex, multifactorial, chronic, recurrent and progressive disease characterised by an abnormal or excessive accumulation of fat which can be harmful to health.1,2 Obesity has been identified as a worldwide public health problem and a major determinant of disability and death.1

The WHO recently published the World Obesity Atlas 2023 on the impact of obesity. According to this report, the current prevalence of obesity in the adult population in Spain is 24%, and the estimated prevalence for 2035 is 37%. It also states that the costs related to obesity and overweight in 2020 amounted to more than $29,784 million, and estimates that costs will increase by 47% by 2035, equivalent to 2.4% of Spain's GDP.3

In accordance with WHO recommendations, the body mass index (BMI) expressed in kg/m2 is used to define and diagnose obesity. In adults, the WHO defines overweight as a BMI of 25.0–29.9 and obesity as a BMI ≥ 30.0. Within obesity, there are three classes: class I (BMI 30−34.9); class II (BMI 35−39.9); and class III (BMI ≥ 40). However, BMI has serious limitations and the current approach to obesity diagnosis is being rethought in favour of body fat percentage, its distribution and muscle function.4

Obesity increases the likelihood of a number of diseases linked to higher mortality rates. A 2016 European Union report ranks obesity as the fourth leading independent cause of death and responsible for 10%–13% of premature deaths. These include type 2 diabetes (DM2), cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension (HTN), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, several types of cancer, obstructive sleep apnoea, osteoarthritis and depression.5 The recent RESOURCE study, a survey conducted in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the UK to assess comorbidities, healthcare resource use and weight loss strategies of people with obesity, showed that more than 25% of people with obesity have at least three concomitant comorbidities, the most common being DM2, HTN and hyperlipidaemia.6 Specific treatment of obesity which achieves a reduction of at least 10% in total body weight has a significant impact on morbidity and mortality rates. Additionally, successful obesity intervention can prevent the development of DM2 by up to 80%, HTN by 55%, coronary heart disease by 35% and adult cancers by approximately 20%.7

In recent years, more factors involved in the development of obesity have been identified and more research has been done on how gut hormones, adipose tissue or gut microbiota regulate appetite and satiety in the hypothalamus. Also, we know that genetic factors play a key role in determining an individual's predisposition to weight gain and recent epigenetic studies have provided useful tools for understanding the worldwide rise in obesity.8

Epidemiology and clinical relevance of obesity in inflammatory bowel diseaseThe incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is increasing rapidly and in parallel with the worldwide obesity epidemic,9 particularly in newly industrialised countries whose societies have become more westernised. Although the incidence of IBD is stabilising in Western countries, its impact remains high, with a prevalence of over 0.3%.10 In Spain, the incidence of IBD is more than 16 cases/100,000 person-years.11 Several environmental factors have been implicated in these epidemiological trends; smoking, improved hygiene standards, infections and antibiotic use, and dietary factors such as diets high in fat or low in fibre.12,13

In contrast to the high prevalence of malnutrition once observed in IBD patients due to inflammation and malabsorption, the current prevalence of obesity in IBD patients is considerable, with an estimated 15%–40% of adult IBD patients being obese and 20%–40% overweight, with no differences according to the type of IBD.9,12–16 This trend is also shared in paediatric patients.17,18 Two cross-sectional studies found the prevalence of grade II-IV obesity in IBD to be 1%–4.4%.16,19

This high prevalence may be independent of the IBD itself, and has been linked to smoking cessation, corticosteroid use and the use of biologic drugs.20 However, obesity in adolescence and early adulthood, as well as pre-pregnancy obesity, has been considered a risk factor for the development of Crohn's disease (CD), but not for ulcerative colitis (UC), although these data are subject to debate.21–25 Obesity is a state of chronic low-grade inflammation with a sustained increase in the production of inflammatory mediators. More specifically, central/visceral adipose tissue is a metabolically active compartment with a marked pro-inflammatory pattern and may be a better predictor of IBD risk than overall obesity as determined by BMI.22,26 Moreover, as in IBD, obesity has been associated with intestinal barrier dysfunction, bacterial translocation, loss of intestinal immune homeostasis and dysbiosis, which may also contribute to the development and perpetuation of intestinal inflammation.12,13

Data on the impact of obesity on IBD are conflicting and potentially limited by the use of BMI.12,15,24,27 Overall, in cross-sectional studies obesity has been variably associated with less aggressive IBD phenotypes, with a lower prevalence of penetrating complications, but with a comparable risk of stricture and perianal complications.19,24,27,28 However, other studies show greater treatment requirements, earlier surgical intervention, longer hospitalisations and a higher incidence of perianal complications and colorectal cancer, resulting in a higher utilisation of healthcare resources.13,29–34 Central/visceral obesity, specifically, has been associated with an increased risk of penetrating and stricturing complications, a shorter time interval to surgery and an increased risk of postoperative recurrence of CD.35,36 Grade III obesity is specifically associated with an increased risk of persistent inflammatory activity with higher C-reactive protein levels in the absence of inflammation, increased risk of clinical recurrence and poorer quality of life in IBD patients, but does not appear to increase the need for immunomodulators or biologic agents, nor does it appear to increase hospitalisation and surgery rates.16,29

Obesity has been associated with a poorer response to treatment in general. Patients with obesity, particularly those with grade III obesity, are less likely to receive optimal weight-appropriate therapy. Suboptimal concentrations of thiopurine metabolites have been reported more frequently in patients with obesity,37 but not of other small molecules such as tofacitinib.38,39 Probably for this reason, an increased risk of primary failure and secondary loss of response has been reported to some biological agents, such as anti-TNF and anti-integrins, regardless of the method of administration and dosing regimens,12,15,40–45 although these findings have not been corroborated in all studies.46,47 In the case of ustekinumab, patients with obesity have lower drug levels but no impact on clinical efficacy.47 In terms of safety, no increased risk of hospitalisation, surgery or serious infections has been reported in patients with obesity treated with biologics.48,49 Lastly, abdominal surgery in patients with obesity is technically more complex, with a longer operating time and a higher rate of conversion to open surgery and risk of postoperative complications.50–53

How and when to assess obesity in patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseThe peculiarities of the association between obesity and IBD lie in the high risk of sarcopenic obesity,54 which in turn is associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. The loss of muscle mass and function is multifactorial (poor dietary intake, protein hypercatabolism, malabsorption during the active phases of the disease and lack of mechanical load on the muscle).55 In addition, corticosteroids used for the treatment of IBD promote selective visceral fat deposition as well as an increased net loss of muscle mass.56 Assessment of obesity in patients with IBD should be performed at the first visit, and reassessed at least annually. Appropriate assessment of patients with IBD and obesity should include the following aspects:

- 1

Diagnosis of obesity and sarcopenia by anthropometry (BMI calculation, waist circumference), body composition techniques (for example, multi-frequency electrical bioimpedance) and functionality tests (hand grip, chair test).56

- 2

Assessment of metabolic disease associated with obesity (DM2, HTN, dyslipidaemia, cardiovascular disease, fatty liver). A detailed medical history and blood tests including blood count, fasting blood glucose, glycosylated haemoglobin, insulinaemia, calculation of insulin resistance index, liver profile and calculation of indices of metabolic liver disease,57 thyroid hormones, anaemia, protein, lipid profile and renal function (including microalbuminuria) will be required. Lastly, liver ultrasound and elastography should be performed to assess the degree of fatty liver disease and liver fibrosis.58

Until recently, obesity was erroneously considered to be a condition related to voluntary lifestyle choices and a problem of excess weight, and recommendations were based on “eat less and move more”.59–61 Dietary treatment remains the first-line option in the management of obesity. Dietary treatment can achieve up to 5% reduction in body weight, although follow-up and behavioural support of patients is necessary to ensure maintenance of the lost weight; otherwise, most of the weight may be regained within three to five years.62–64 This is because, when calorie restriction is undertaken, the metabolic adaptation mechanism (increased hunger and reduced resting energy expenditure) is activated in proportion to the rate of weight loss.65

Currently, the Sociedad Española para el Estudio de la Obesidad (SEEDO) [Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity]66 recommends the use of the balanced low-calorie diet (based on a deficit of 500−600 kcal/day over the resting energy expenditure measured by direct methods)67 and the Mediterranean diet (low in saturated, trans fatty acids and simple carbohydrates, rich in vegetable fibre and monounsaturated fatty acids).68 There are other types of diets, such as dissociated diets, exclusion diets and very low calorie diets, but they lack sufficient scientific evidence in IBD patients.

Scientific evidence on intentional weight loss through diet in patients with IBD and obesity is limited. Decreases in body weight and waist circumference as well as an improvement in metabolic liver disease have been observed in patients with IBD who followed a Mediterranean diet for six months, with a positive impact on IBD.69 These effects have also been reported in other immune-mediated diseases.70 However, we lack specific evidence on the efficacy and safety of supervised dietary strategies for the treatment of grade III obesity in patients with IBD.

Dietary recommendations for patients with IBD and obesity, as in patients with obesity in general, should be based on clear goals of losing fat mass and preserving lean mass, incorporating high biological value protein and controlling the energy density of foods, and be varied and fractionated. Lack of response or regaining of weight should not necessarily be attributed to patient lack of willpower or non-compliance.

Recommendations on the dietary management of obesity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease- -

In patients with IBD and obesity, an early approach to obesity is recommended to mitigate its impact on both their general health and on the IBD.

- -

Dietary management of obesity in IBD patients should preferably be carried out in the clinical remission phase of IBD.

- -

It is advisable to promote gradual weight loss through supervised and adapted dietary strategies and increased physical activity.

- -

Dietary support for the treatment of grade III obesity in patients with IBD should be carried out in referral centres which can guarantee the correct nutritional approach and follow-up of IBD, always within a multidisciplinary team.

- -

It is recommended to promote healthy dietary habits:

- o

Consumption of lean meats and white fish. Eating fish 3–4 times a week and limiting red meat consumption to twice a week are recommended.

- o

Avoid mass-produced cakes and pastries and ultra-processed foods.

- o

Incorporate preferably plant-based foods into the diet. Depending on digestive tolerance, consider eating whole grains, fruit, vegetables and pulses.

- o

Encourage low-fat dairy products.

- o

Among the so-called anti-obesity medications (AOM), the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has approved the following as long-term pharmacotherapy for obesity: orlistat; liraglutide; semaglutide; the combination of bupropion and naltrexone; and setmelanotide.71 Lorcaserin and the combination phentermine/topiramate, available only in the US, have not been approved by the EMA.

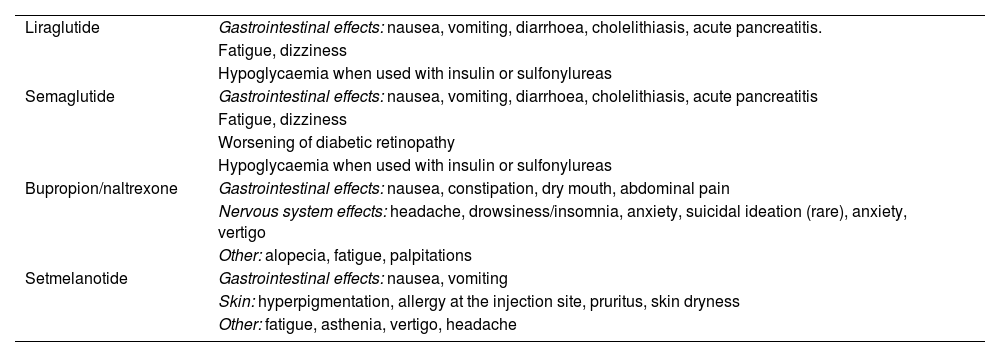

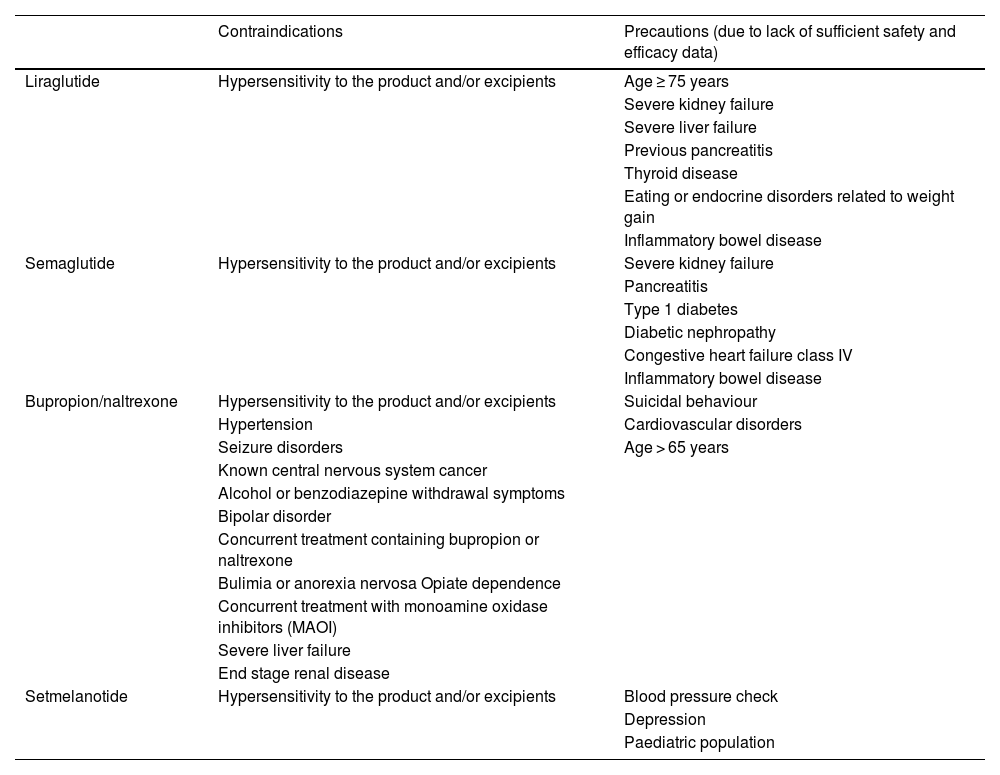

AOM are indicated in combination with lifestyle modification for the management of overweight and obesity in those who have tried to improve their lifestyle and continue to have a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 or ≥27 kg/m2 associated with obesity-related comorbidity such as HTN, DM2, dyslipidaemia or sleep apnoea. A summary of the most common adverse reactions and contraindications of these drugs is shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Most common adverse reactions of anti-obesity medications.

| Liraglutide | Gastrointestinal effects: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, cholelithiasis, acute pancreatitis. |

| Fatigue, dizziness | |

| Hypoglycaemia when used with insulin or sulfonylureas | |

| Semaglutide | Gastrointestinal effects: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, cholelithiasis, acute pancreatitis |

| Fatigue, dizziness | |

| Worsening of diabetic retinopathy | |

| Hypoglycaemia when used with insulin or sulfonylureas | |

| Bupropion/naltrexone | Gastrointestinal effects: nausea, constipation, dry mouth, abdominal pain |

| Nervous system effects: headache, drowsiness/insomnia, anxiety, suicidal ideation (rare), anxiety, vertigo | |

| Other: alopecia, fatigue, palpitations | |

| Setmelanotide | Gastrointestinal effects: nausea, vomiting |

| Skin: hyperpigmentation, allergy at the injection site, pruritus, skin dryness | |

| Other: fatigue, asthenia, vertigo, headache |

General contraindications for anti-obesity medications.

| Contraindications | Precautions (due to lack of sufficient safety and efficacy data) | |

|---|---|---|

| Liraglutide | Hypersensitivity to the product and/or excipients | Age ≥ 75 years |

| Severe kidney failure | ||

| Severe liver failure | ||

| Previous pancreatitis | ||

| Thyroid disease | ||

| Eating or endocrine disorders related to weight gain | ||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | ||

| Semaglutide | Hypersensitivity to the product and/or excipients | Severe kidney failure |

| Pancreatitis | ||

| Type 1 diabetes | ||

| Diabetic nephropathy | ||

| Congestive heart failure class IV | ||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | ||

| Bupropion/naltrexone | Hypersensitivity to the product and/or excipients | Suicidal behaviour |

| Hypertension | Cardiovascular disorders | |

| Seizure disorders | Age > 65 years | |

| Known central nervous system cancer | ||

| Alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms | ||

| Bipolar disorder | ||

| Concurrent treatment containing bupropion or naltrexone | ||

| Bulimia or anorexia nervosa Opiate dependence | ||

| Concurrent treatment with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI) | ||

| Severe liver failure | ||

| End stage renal disease | ||

| Setmelanotide | Hypersensitivity to the product and/or excipients | Blood pressure check |

| Depression | ||

| Paediatric population |

Orlistat is a pancreatic lipase inhibitor, which decreases the absorption of fats from the diet. Its efficacy in relation to weight loss is poor and its use as an AOM has fallen into disuse.

Liraglutide is an analogue of glucagon-like peptide type 1 (GLP-1). GLP-1 is released in response to food intake and has receptors in the hypothalamus and gut through which it increases satiety. It is contraindicated in thyroid cancer, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, pancreatitis and during pregnancy and breast-feeding. The most common associated adverse effects are gastrointestinal, such as nausea and abdominal pain. Its efficacy in terms of loss of baseline weight is around 5%–8%.72 It is administered daily, subcutaneously in a multi-dose pre-filled pen, with the dose being increased weekly according to gastrointestinal tolerance. Another GLP-1 analogue is semaglutide, with similar mechanisms of action and contraindications to liraglutide but with greater efficacy, achieving weight loss of around 9%–16% of initial weight.73 It is administered weekly, subcutaneously in a pre-filled multi-dose pen, with the dose being increased monthly according to gastrointestinal tolerance.

The combination of naltrexone and bupropion acts at the level of the hypothalamus to stimulate satiety by a dual mechanism; it stimulates the production of propiomelanocortin and melanocortin, and blocks endorphin receptors and the pleasure associated with eating. Its effectiveness in terms of weight loss is around 5% of initial weight.74

Finally, setmelanotide is a selective agonist of brain MC4 receptors involved in the regulation of hunger, satiety and energy expenditure. It is indicated for the treatment of monogenic obesity due to propiomelanocortin, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 (PCSK1) and leptin receptor (LEPR) deficiency.71

Published data on the pharmacological treatment of obesity in IBD are limited. A recent retrospective US study found a low rate of AOM prescribing in patients with IBD. Of a total of 286,760 adult IBD patients, 37% were obese; among them, only 2.8% were prescribed AOM during the study period. Prescribing rates increased from 1.4% to 3.6% between 2010 and 2019, reflecting a clear discrepancy between the exponential increase in obesity in IBD patients and AOM prescribing, probably related to the current lack of recommendations on the subject.75

To date, there have been no randomised clinical trials (RCT) of AOM in IBD patients. Therefore, it is not possible to formulate any specific indication in this respect and recommendations must be based on the mechanism of action of the drugs, known adverse effects and the limited data available in this setting.

The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) and United European Gastroenterology (UEG) have recently published their joint recommendations on the management of obesity in patients with gastrointestinal disorders.76 They consider that any of the drugs described above, except orlistat, can be used in patients with IBD. Orlistat, due to its mechanism of action, may cause gastrointestinal symptoms such as increased bowel movements, urgency, incontinence and marked steatorrhoea, and is therefore contraindicated in patients with malabsorption and not recommended in patients with IBD. Liraglutide may positively affect the homeostasis of the intestinal immune system.77,78 However, as with semaglutide, no data are available on weight loss induced with these drugs in patients with IBD and obesity. In addition, a Danish population-based study compared the estimated incidence of a combined target (use of corticosteroids, anti-TNF, surgery or hospital admission) in patients with IBD and DM2 according to whether they had been treated with GLP-1 analogues or other antidiabetic agents, finding a lower incidence of the combined target in those treated with GLP-1 analogues, suggesting a possible positive impact on IBD outcome.79

A prospective study of 47 patients with active IBD refractory to conventional medical treatment showed that naltrexone reduces clinical activity and improves endoscopic findings.80 An RCT in patients with mild-to-moderate CD is currently underway to evaluate the efficacy of naltrexone in inducing clinical/endoscopic remission.81 While these data would support the safety of naltrexone in patients with IBD, they do not provide evidence for its efficacy in terms of weight loss. Bupropion has also been associated with clinical remission in some CD cases reported in the literature,82,83 but once again its effect on weight loss has not been described.

Recommendations on pharmacotherapy for obesity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease- -

AOM can currently be considered in patients with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 or a BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 associated with obesity-related comorbidities such as HTN, DM2 or sleep apnoea.

- -

Before starting AOM treatment for obesity, it is recommended that the patient has been in clinical remission with IBD for at least six months.

- -

The general contraindications to AOM treatments in patients with IBD are the same as those established for patients without IBD.

- -

AOM drugs can be used in patients with IBD, with the exception of orlistat, due to its mechanism of action and associated gastrointestinal adverse effects, but there is no recommendation in favour of any specific anti-obesity drug in these patients, given the lack of controlled studies in patients with IBD. In these patients, it seems reasonable that the prescribing and follow-up of these treatments should be carried out in referral centres within a multidisciplinary team which can guarantee the correct monitoring of the treatment and of the IBD.

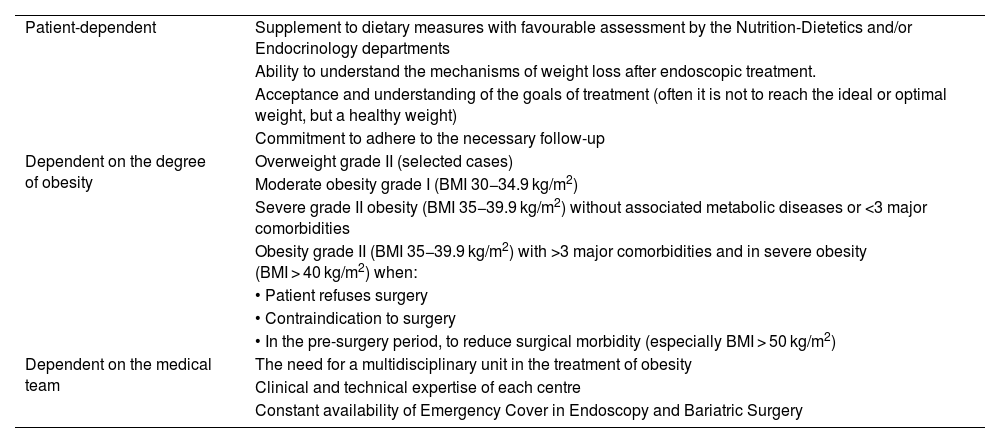

Endoscopic treatment of obesity is often considered in cases with insufficient response to medical treatment alone who are not candidates for surgical treatment; therefore, as a transoral endoluminal procedure it may be considered the middle ground between clinical and surgical management.84–86 The general requirements for performing these techniques are specified in Table 3.

General requirements for endoscopic treatment of obesity.

| Patient-dependent | Supplement to dietary measures with favourable assessment by the Nutrition-Dietetics and/or Endocrinology departments |

| Ability to understand the mechanisms of weight loss after endoscopic treatment. | |

| Acceptance and understanding of the goals of treatment (often it is not to reach the ideal or optimal weight, but a healthy weight) | |

| Commitment to adhere to the necessary follow-up | |

| Dependent on the degree of obesity | Overweight grade II (selected cases) |

| Moderate obesity grade I (BMI 30−34.9 kg/m2) | |

| Severe grade II obesity (BMI 35−39.9 kg/m2) without associated metabolic diseases or <3 major comorbidities | |

| Obesity grade II (BMI 35−39.9 kg/m2) with >3 major comorbidities and in severe obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m2) when: | |

| • Patient refuses surgery | |

| • Contraindication to surgery | |

| • In the pre-surgery period, to reduce surgical morbidity (especially BMI > 50 kg/m2) | |

| Dependent on the medical team | The need for a multidisciplinary unit in the treatment of obesity |

| Clinical and technical expertise of each centre | |

| Constant availability of Emergency Cover in Endoscopy and Bariatric Surgery |

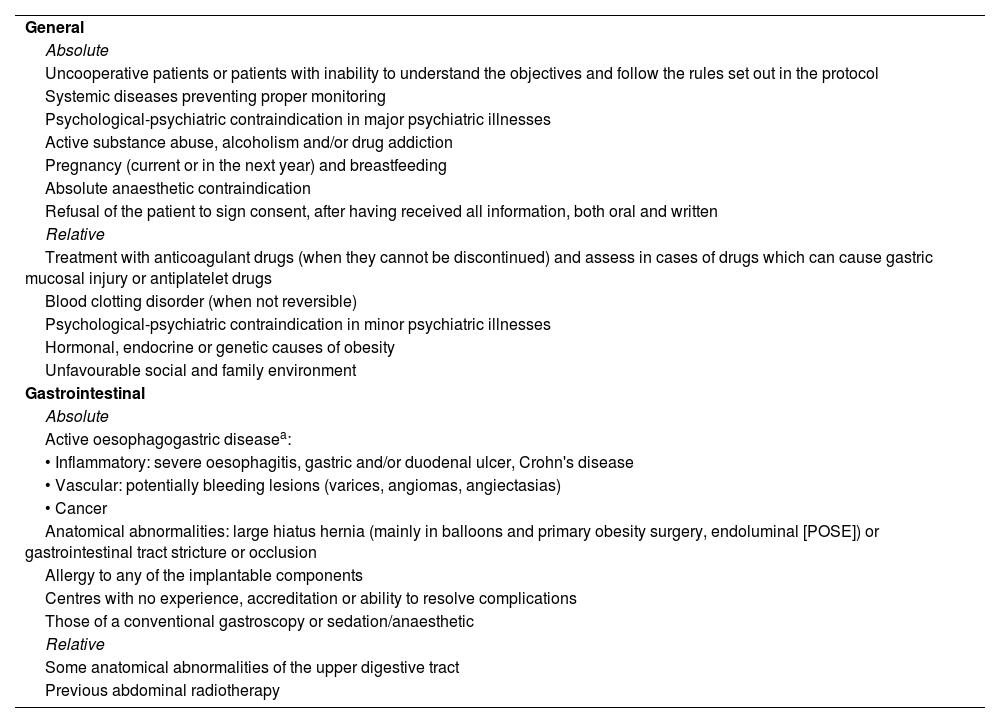

As a first-line treatment it would be indicated in selected cases of overweight, in grade I obesity and in grade II obesity with less than three comorbidities. It may also be indicated as an alternative in patients with grade II obesity with comorbidities and grade III obesity who refuse surgery or in whom surgery is contraindicated. Lastly, it may be an option in cases of super-obesity (BMI > 50 kg/m2) as a bridge therapy to subsequent bariatric surgery. Table 4 summarises the main contraindications for endoscopic treatment of obesity.

General contraindications to endoscopic treatment of obesity.

| General |

| Absolute |

| Uncooperative patients or patients with inability to understand the objectives and follow the rules set out in the protocol |

| Systemic diseases preventing proper monitoring |

| Psychological-psychiatric contraindication in major psychiatric illnesses |

| Active substance abuse, alcoholism and/or drug addiction |

| Pregnancy (current or in the next year) and breastfeeding |

| Absolute anaesthetic contraindication |

| Refusal of the patient to sign consent, after having received all information, both oral and written |

| Relative |

| Treatment with anticoagulant drugs (when they cannot be discontinued) and assess in cases of drugs which can cause gastric mucosal injury or antiplatelet drugs |

| Blood clotting disorder (when not reversible) |

| Psychological-psychiatric contraindication in minor psychiatric illnesses |

| Hormonal, endocrine or genetic causes of obesity |

| Unfavourable social and family environment |

| Gastrointestinal |

| Absolute |

| Active oesophagogastric diseasea: |

| • Inflammatory: severe oesophagitis, gastric and/or duodenal ulcer, Crohn's disease |

| • Vascular: potentially bleeding lesions (varices, angiomas, angiectasias) |

| • Cancer |

| Anatomical abnormalities: large hiatus hernia (mainly in balloons and primary obesity surgery, endoluminal [POSE]) or gastrointestinal tract stricture or occlusion |

| Allergy to any of the implantable components |

| Centres with no experience, accreditation or ability to resolve complications |

| Those of a conventional gastroscopy or sedation/anaesthetic |

| Relative |

| Some anatomical abnormalities of the upper digestive tract |

| Previous abdominal radiotherapy |

Whichever the case, prior personalised review by a multidisciplinary team should be carried out, including dietetic and/or endocrine, psychological, anaesthetic and endoscopic assessments. Furthermore, it is considered inadvisable to perform these techniques in centres that do not have a minimum of accredited experience or the capacity to deal with or resolve potential complications.

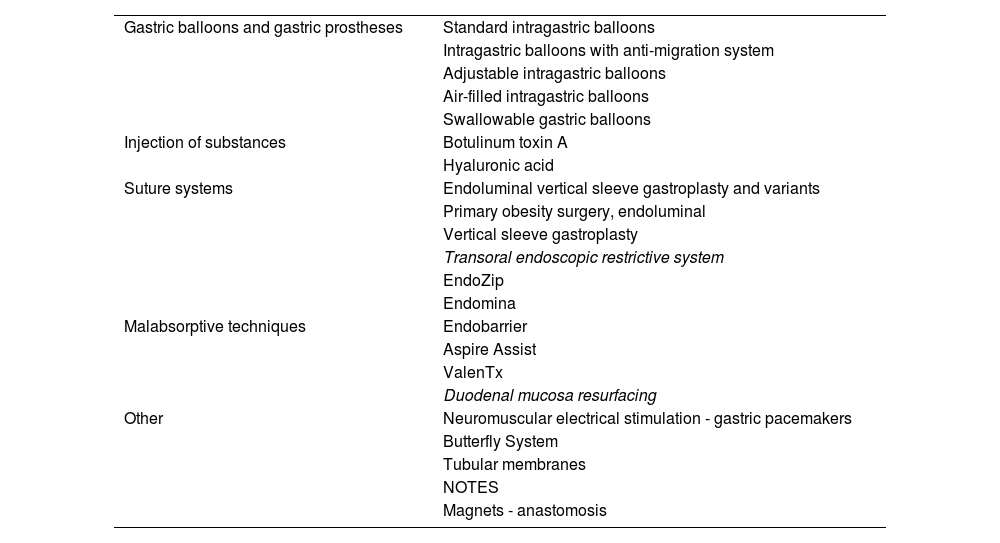

Table 5 shows the techniques currently available for the endoscopic treatment of obesity. Among them, the most advanced are intragastric balloons and suture systems. The intragastric balloon is an intraluminal space-occupying device that works by reducing gastric volume and delay in gastric emptying and regulating gastrointestinal hormones.87–90 There are more than 15 commercially available models that differ in duration, morphology, material, type and volume of filling, readjustment capacity and endoscopic requirement for insertion/removal.86,91 Overall, they achieve an average weight loss of >10% in >75% of treated patients92,93 and a significant improvement in comorbidities related to metabolic syndrome.94–97

Current main possibilities in the endoscopic treatment of obesity.

| Gastric balloons and gastric prostheses | Standard intragastric balloons |

| Intragastric balloons with anti-migration system | |

| Adjustable intragastric balloons | |

| Air-filled intragastric balloons | |

| Swallowable gastric balloons | |

| Injection of substances | Botulinum toxin A |

| Hyaluronic acid | |

| Suture systems | Endoluminal vertical sleeve gastroplasty and variants |

| Primary obesity surgery, endoluminal | |

| Vertical sleeve gastroplasty | |

| Transoral endoscopic restrictive system | |

| EndoZip | |

| Endomina | |

| Malabsorptive techniques | Endobarrier |

| Aspire Assist | |

| ValenTx | |

| Duodenal mucosa resurfacing | |

| Other | Neuromuscular electrical stimulation - gastric pacemakers |

| Butterfly System | |

| Tubular membranes | |

| NOTES | |

| Magnets - anastomosis |

Although the intragastric balloon has been the most widely used in clinical practice and the most studied for the treatment of obesity, there are no studies assessing efficacy and safety in patients with IBD. In fact, oesophagogastroduodenal involvement in CD has classically been an absolute contraindication for this technique.86,98,99 There is only one published case of exacerbation of UC in a patient on treatment with mesalazine who had an intragastric balloon implanted; the balloon had to be removed early, with the exacerbation being attributed to inadequate drug release secondary to slowed gastric emptying.100

Various suture systems are currently available. The initial POSE method, which created 8–10 transmural folds in the gastric fundus and another 2–4 in the distal body, has given way to POSE 2.0™ (Endo-Sleeve) which makes 16–20 folds in the greater curvature of the gastric body, reducing the gastric volume and shortening it in length. These techniques exert a mechanical restrictive effect, decrease intake capacity and induce hormonal changes which result in an early increase in satiety. An average loss of 15%–18% of total body weight over 6–12 months has been reported.101,102 The rate of adverse effects is 1%–5%, with self-limited bleeding due to suture pressure being the most common.103–106Endoscopic vertical sleeve gastroplasty (Endosleeve, Apollo® System) consists of performing 4–6 continuous transmural sutures in the greater curvature of the gastric body, achieving a tubular gastric restriction.107 A mean loss of 18% of total body weight at 18 months has been reported,108–110 maintaining a 16% loss at five years with a decrease in associated comorbidities.111–113 The reported complication rate is 1%–2%, mainly gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal pain and peri-gastric collections.108–110

There is currently no quality evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of other endoscopic procedures for weight loss in patients with IBD and grade III obesity. Pugliese et al.114 reported a case of a patient with UC in clinical remission on treatment with infliximab who had an endoscopic Endo-Sleeve procedure with good outcomes in terms of weight loss and no negative impact on her IBD.

Recommendations on endoscopic management of obesity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease- -

The indication for endoscopic treatment of grades II and III obesity in patients with IBD should generally follow the same criteria as those established for patients without IBD.

- -

Before considering any endoscopic procedure for the treatment of obesity, it is recommended that the patient has been in clinical remission with IBD for a minimum period of six months.

- -

The general contraindications to endoscopic treatments for grades II and III obesity in patients with IBD are very similar to those established for patients without IBD.

- -

Bariatric endoscopic techniques in patients with IBD and grade III obesity are contraindicated when IBD or other associated systemic disease may prevent adequate follow-up, there have been signs of activity during the last six months, or the patient has a history of IBD with oesophagogastric or proximal small bowel involvement or suspected and/or existing gastrointestinal tract stricture/occlusion.

- -

Endoscopic treatments for obesity in patients with IBD should be performed in referral centres with clinical and technical expertise and availability of joint management of endoscopic bariatric and IBD treatment.

- -

Patients with IBD who have been fitted with an intragastric balloon should receive uninterrupted proton pump inhibitor therapy for as long as the balloon remains in place.

- -

In patients with IBD who have had an intragastric balloon placed and have a flare-up of IBD activity, removal of the balloon should be considered, depending on the involvement and severity of the flare-up.

- -

In patients with IBD and grade III obesity in whom endoscopic bariatric treatment is considered, endoscopic suturing (endosleeve) should be the recommended technique as a minimally invasive, safe and reversible alternative to surgery.

Metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) is the most effective treatment for patients with severe obesity who do not respond to conservative treatment (diet, exercise, behavioural modification or pharmacotherapy). It achieves adequate and sustained weight loss in a very high percentage of patients, with a high rate of resolution of comorbidities, and significantly improves quality of life and survival, although a significant percentage of patients regain the lost weight after the surgery.115,116

In 1991, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) expert committee convened a consensus conference, which resulted in the indications for obesity surgery being established; these indications were accepted by the different surgical societies and most bariatric surgical teams have relied on them for many years.117 They were subsequently reviewed and accepted by the Sociedad Española de Cirugía de la Obesidad (SECO) [Spanish Society of Obesity Surgery] in the Salamanca118 and Vitoria-Gasteiz119 declarations. In 2022, the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) produced a new document which updates the previously described indications, in particular the following120:

- -

MBS is recommended for individuals with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2, regardless of the presence, absence or severity of associated comorbidities.

- -

MBS will be considered in individuals with metabolic disease and BMI between 30 and 34.9 kg/m2 who do not achieve sufficient or sustained weight loss or improvement of their comorbidities through non-surgical treatments.

- -

The long-term outcomes of MBS consistently demonstrate its safety and efficacy, as well as its durability in the treatment of severe obesity and its comorbidities.

- -

There is no upper age limit for MBS. Older adults who may benefit from MBS should be considered for MBS after careful consideration of their comorbidities and frailty.

- -

With appropriate screening, children and young people can be considered as potential candidates for MBS.

In the case of patients with IBD and obesity, recent European guidelines state that MBS is indicated in case of BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 or ≥35 kg/m2 associated with comorbidities and with previous failure of dietary and pharmacological anti-obesity measures.76 A recent systematic review showed that MBS is safe and effective for patients with IBD and obesity, achieving significant weight loss at both six months and 12 months post-intervention.121 This weight loss reduces inflammation in IBD patients and may therefore improve the course of their disease as well as associated comorbidities, so IBD is not a contraindication to MBS.122,123

Since its inception, MBS has evolved technically and is now supported by strong evidence of efficacy and safety.124 According to the consensus recommendations of the Asociación Española de Cirujanos (AEC) [Spanish Association of Surgeons] and SECO,125 the mortality rate in bariatric surgery should be less than 0.5%. The overall early morbidity rate (first 30 days) is below 7% in the most experienced centres (depending on the surgical technique as well as the volume of procedures performed). The weight loss results of MBS are consistently maintained for years after surgery at greater than 60% excess weight loss, with some variation depending on the surgery performed.120

Bariatric surgery must currently be performed by minimally invasive surgery (laparoscopy and/or robotics), thus achieving advantages for the patient in terms of early recovery and fewer postoperative complications. Functionally, surgical techniques could be divided into pure restrictive, mixed (with restrictive and hypoabsorptive component) and mixed, predominantly malabsorptive. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and adjustable gastric banding (increasingly less common) are the main pure restrictive procedures, where the main objective is the reduction of gastric volume. The main mixed techniques (where in addition to gastric restriction an intestinal bypass is performed in order to reduce absorption, mainly of fat) are laparoscopic gastric bypass and one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB). As mixed but predominantly malabsorptive techniques, the Scopinaro biliopancreatic diversion and the duodenal switch are currently being replaced by single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S).

There are currently no absolute contraindications for MBS other than excessive surgical risk, life expectancy of less than five years or an oncological process which has not been in complete remission for more than five years or an active severe infectious process, decompensated liver cirrhosis, untreated severe depression or psychosis, uncontrolled or untreated eating disorders, active abuse of drugs and alcohol, severe clotting disorders and, most importantly, inability to meet nutritional requirements, especially lifelong vitamin replacement. There are no age limits for MBS. However, frailty is considered the best predictor of the development of complications. It is worth remembering that MBS is an effective treatment for clinically severe obesity in patients who require other specialised surgery such as arthroplasty, repair of abdominal wall defects or organ transplantation. Similarly, there are no total contraindications regarding the choice of surgical technique, although restrictive techniques are generally avoided in patients with severe gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, Barrett's oesophagus, oesophageal motor disorders or large hiatus hernia. In the case of hypo- or mixed-absorptive techniques, diseases that impair absorption or decompensated liver disease are usually considered as contraindications.126

In selected patients with controlled IBD, MBS is safe, with a low rate of postoperative complications (comparable to patients without IBD), and effective, in relation to good weight loss at 12 months (being somewhat better for gastric bypass than for restrictive techniques). An American population-based study analysed the type of MBS performed in patients with IBD and obesity, reporting that 48% of patients underwent sleeve gastrectomy, 35%, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and 17%, gastric banding.123 However, there are no RCT or prospective studies available comparing different bariatric surgical techniques in patients with IBD. Current scientific evidence regarding the phenotype, clinical features of IBD and the impact of MBS on the course and therapeutic requirements of IBD is based on limited clinical case reports.

There are multiple published series and reviews on the characteristics of patients with IBD and obesity undergoing MBS, as well as its efficacy and safety.127–137 The most common type of IBD undergoing MBS is CD, accounting for approximately two thirds of cases. In CD, the location of the disease is predominantly ileocolonic and of an inflammatory or stricturing phenotype. The most commonly used surgical procedure is sleeve gastrectomy. Given that approximately half of CD patients will require intestinal resection at some point (mainly with resection of the ileocaecal valve and terminal ileum), it seems reasonable to avoid malabsorptive MBS, and restrictive surgical techniques are recommended, with sleeve gastrectomy being the technique of choice. In addition, the potential to develop disease-specific intestinal complications such as strictures, abscesses or fistulae, both at the level of the excluded intestine and the “functional” intestine in the case of malabsorptive techniques, could be a major problem in terms of management and assessment. There is a higher proportion of patients with UC who have undergone Roux-en-Y gastrectomy.

A recent North American study at two referral centres analysed the clinical course of IBD in a group of severely obese patients; patients who underwent MBS had a lower rate of IBD-related complications compared to those who did not have surgery, suggesting a positive impact of weight loss on the course of the disease.136 In a French multicentre study, Reenaers et al.134 compared the efficacy and safety of MBS in obese patients with and without concomitant IBD, reporting that there were no differences between the two study groups in weight loss, development of anaemia or iron or cobalamin deficiency at follow-up. In a study conducted from a registry of patients admitted between 2011 and 2013, Bazerbachi et al.,133 compared the risk of early and late complications after MBS in a total of 314,864 obese patients, 790 of whom had IBD; the study showed that the only difference in terms of post-surgical complications was a higher rate of small bowel obstruction in patients with IBD. Lastly, a recent meta-analysis compared the safety of sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y bypass in 168 patients with IBD, demonstrating a much higher rate of both early and late complications in the bypass patients (45.6% vs 21.6%).137

The possibility of developing IBD following MBS has recently been described. To date, 17 cases of UC, 60 cases of CD and three cases of IBD unclassified have been reported.138–147 The largest published series included 44 incident IBD cases (31 with CD) from an American prospective registry of 3709 patients who underwent MBS.146 Of the total number of reported cases, baseline characteristics could be inferred for 73 patients,148 with a median pre-MBS BMI of 47 and a median age of 45. Roux-en-Y bypass was the most commonly used surgical procedure (80% of cases). Symptoms potentially related to IBD (diarrhoea, abdominal pain and weight loss not explained by the bariatric procedure) occurred between one month and 16 years after the surgical procedure. Phenotypically, the most common location of CD was ileocolic (44%) and ileal (31%), and the extent of UC was extensive in 50% and left-sided in 25%. CD patients required mostly (90%) advanced pharmacotherapies (25% thiopurines and 32% biologics), and only 11% required surgery during follow-up.

Case reports suggest a possible association between MBS and the development of de novo IBD, particularly CD, with intestinal dysbiosis and cytokine release from adipose tissue as a result of anatomical changes and massive weight loss in genetically susceptible patients being postulated as possible precipitating pathophysiological mechanisms. Another hypothesis suggested is the existence of pre-clinical IBD prior to MBS. The development of IBD after MBS and the mechanisms that explain it are not yet fully understood and it cannot be ruled out that it is due to the obesity itself or simply chance.

Last of all, it is important to remember that MBS can induce nutritional deficiencies, especially in the short and medium term, so the SEEDO recommendations regarding systematic supplementation after MBS should be followed,149 with this being even more vital for patients with underlying IBD.

Recommendations on the surgical management of obesity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease- -

In patients with IBD and obesity, bariatric surgery is indicated in cases of BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 or ≥35 kg/m2 associated with comorbidities and with previous failure of dietary and pharmacological anti-obesity measures.

- -

Patients with IBD who are candidates for bariatric surgery should be free of active disease at the time of surgery and in the best possible nutritional state, with the intention of minimising postoperative complications.

- -

Bariatric surgery for the treatment of obesity in patients with IBD should be performed in referral centres with experience in bariatric surgery and where IBD follow-up can be performed, always within a multidisciplinary team.

- -

In patients with ulcerative colitis, any type of bariatric surgery can be performed. In patients with a higher risk of colectomy, restrictive techniques are those of choice.

- -

In patients with Crohn's disease, a detailed assessment of the location of the disease is recommended prior to surgery to rule out upper gastrointestinal involvement by magnetic resonance enterography or capsule endoscopy.

- -

In patients with Crohn's disease, it is recommended to avoid techniques with a malabsorptive component. Laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy is a good option as it preserves future surgical options by not altering the intestinal anatomy.

- -

After bariatric surgery, existing recommendations on nutrient supplementation and monitoring should be followed.

Management of the patient with IBD and severe obesity should follow a similar approach to patients without IBD. Referral to a multidisciplinary unit specialising in obesity is recommended, at least for a personalised approach to the therapeutic options, for patients with IBD and a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2, as well as cases with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 with associated metabolic disease (mainly fatty liver disease and DM2) or other complications of obesity (gastro-oesophageal reflux, joint disease - in particular osteoarthritis of the knee - and obstructive sleep apnoea).

When patients come from primary care, the SEEDO-SEMERGEN (Sociedad Española de Médicos de Atención Primaria [Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians]) referral criteria and circuits150 should be used. It is also recommended that all health professionals involved in the care of these patients participate in the multidisciplinary committees in which the therapeutic strategy is designed.

Considering that obesity is a chronic and recurrent disease and that shared decision-making needs to be encouraged for managing the condition, the “5 As strategy” (ask, assess, advise, agree and assist) is recommended. During this process it is important to avoid simplistic approaches to the origin of the disease or which lack scientific evidence to support them, and above all, avoid stigmatising patients.

The assessment of therapeutic options for severe obesity in patients with IBD should be made according to current clinical practice guidelines,120,151,152 with a personalised approach, taking into account the previously mentioned risks/benefits in the context of IBD (for example, potential impact on disease progression, risk of malnutrition and associated sarcopenia).

All patients who are diagnosed with IBD during the pre-bariatric surgery assessment process or who have been referred for obesity treatment and are not under follow-up or have not recently had their IBD assessed should be assessed by a specialised IBD care unit. With the limited evidence available and in order to minimise the risk of complications associated with obesity treatment, it would be necessary for the patient with IBD and obesity to be in clinical, biological and endoscopic/morphological remission for at least six months before undergoing endoscopic treatment or MBS. Therefore, it seems reasonable to recommend that during the 6–12 months prior to the endoscopic or surgical procedure the patient should have: 1) absence of gastrointestinal symptoms related to their IBD (mainly in terms of bowel habit changes and abdominal pain in CD and rectal bleeding and number of bowel movements in UC); and 2) normal biological markers (faecal calprotectin or C-reactive protein). In addition, in the six months prior to obesity treatment (pharmacotherapy, endoscopic or surgical), the absence of active inflammatory lesions should be confirmed by imaging tests (colonoscopy in the case of colon or terminal ileum involvement and magnetic resonance enterography or intestinal ultrasound for the small intestine).

Following the endoscopic procedure or MBS, close monitoring is recommended with a first clinical-biological assessment three months after the procedure. In this regard, it should be noted that there are limited data on the impact of MBS or endoscopic treatments on faecal calprotectin levels. In CD, an immediate increase in faecal calprotectin has been reported after ileocolic resection, which usually returns to normal three months after surgery,153 so this should be taken into account if the biomarker is used in early patient monitoring. A recent study in 30 patients undergoing Roux-en-Y bypass for obesity (without known IBD) evaluated different plasma and faecal biomarkers before and six months after MBS. Among the faecal biomarkers, calprotectin levels were determined, showing a significant increase at six months (median 38 μg/g baseline, 297 μg/g at six months).154 However, endoscopic assessment and subsequent monitoring were not available.

Recommendations on the assessment of treatment of severe obesity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease- -

Patients with IBD and a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2, and those with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 and associated metabolic disease, should be referred to centres with a multidisciplinary obesity unit and an accredited IBD unit for a personalised approach to treatment options.

- -

Patients who are diagnosed with IBD during the pre-bariatric surgery assessment process or who have been referred for obesity treatment and are not under follow-up or have not recently had their IBD assessed should be assessed by an accredited IBD unit.

- -

During the 6–12 months prior to any endoscopic or surgical procedure for obesity, the patient should remain free of IBD-related gastrointestinal symptoms and have IBD biomarkers within normal range.

- -

In addition, in the six months prior to the start of obesity treatment (pharmacological, endoscopic or surgical), the absence of active inflammatory lesions should be confirmed by imaging tests.

This study did not receive any financial support.

Conflicts of interestEugeni Domènech has received fees for lectures or expert advice, support in attending courses or congresses and donations or grants for events or for research projects from AbbVie, Adacyte Therapeutics, Biogen, Celltrion, Galapagos, Gilead, GoodGut, Imidomics, Janssen, Kern Pharma, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung, Takeda and Tillots.

Andreea Ciudin has received fees for lectures and support in attending or congresses from NovoNordisk, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Esteve, Menarini and MSD.

José María Balibrea has received fees for lectures or expert advice, support in attending courses or congresses and donations or grants for events or for research projects from iVascular, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Abex, BBraun and Smith & Nephew.

Eduard Espinet-Coll is a medical consultant at Apollo Endosurgery.

Fiorella Cañete has received fees for lectures and support in attending courses or congresses from AbbVie, Adacyte Therapeutics, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda and Tillots.

Lilliam Flores has received fees for lectures and support in attending courses or congresses from Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly Spain.

Román Turró is a consultant for USGI Medical, GI Windows and Nitinotes.

Alejandro Hernández-Camba has received fees for lectures and support in attending courses or congresses from AbbVie, Adacyte Therapeutics, Janssen, Pfizer, Ferring, Kern Pharma, Takeda, Galapagos and Tillots.

Ana Gutiérrez has received fees for lectures or expert advice, support in attending courses or conferences and donations or grants for events or for research projects from AbbVie, Adacyte Therapeutics, Celltrion, Galapagos, Janssen, Kern Pharma, MSD, Pfizer, Takeda, Tillots and Lilly.

Yamile Zabana has received fees for lectures or expert advice, support in attending courses or congresses, or support for events from AbbVie, Adacyte, Almirall, Amgen, Dr Falk Pharma, FAES Pharma, Ferring, Janssen, MSD, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shire, Takeda, Galapagos, Boehringer Ingelheim and Tillots.

The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

José María Balibrea. Department of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona; Department of Surgery, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Manuel Barreiro-de Acosta. Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela.

Javier Butragueño. LFE Research Group, Department of Health and Human Performance, Faculty of Physical Activity and Sports Sciences (INEF), Polytechnic University of Madrid.

Fiorella Cañete. Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD) [Biomedical Research Networking Centre for Hepatic and Gastrointestinal Diseases].

Andreea Ciudin Mihai. Endocrinology and Nutrition Department, Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona; Diabetes and Metabolism Research Unit, Vall d'Hebron Institut de Recerca (VHIR), Barcelona; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Diabetes y Enfermedades Metabólicas Asociadas (CIBERDEM) [Biomedical Research Networking Centre for Diabetes and Associated Metabolic Diseases]; Department of Physiology and Immunology, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Ana B. Crujeiras. Epigenomics in Endocrinology and Nutrition Group, Epigenomics Unit, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Santiago de Compostela (IDIS), Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago de Compostela (CHUS) and CIBER Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBERobn) [Biomedical Research Networking Centre for Pathophysiology of Obesity and Nutrition], Santiago de Compostela.

Andrés J. del Pozo-García. Endoscopy Unit, Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid; Hospital Viamed Santa Elena, Madrid.

Eugeni Domènech, Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD); Department of Medicine, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

José Miguel Esteban López-Jamar. Endoscopy Unit, Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid.

Eduard Espinet-Coll. Bariatric Endoscopy Unit, Hospital Universitario Dexeus and Clínica Diagonal, Barcelona.

Manuel Ferrer-Márquez. Department of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas, Almería.

Lilliam Flores. Department of Endocrinology and Nutrition, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona.

M. Dolores Frutos. Department of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Diabetes y Enfermedades Metabólicas Asociadas (CIBERDEM).

Ana Gutiérrez. Gastroenterology Department, Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria y Biomédica de Alicante (ISABIAL) [Alicante Health and Biomedical Research Institute], Alicante; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD).

Alejandro Hernández-Camba. Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de La Candelaria, Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

Míriam Mañosa. Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD); Department of Medicine, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Francisco Rodríguez-Moranta. Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, L'Hospitalet de Llobregat.

Fàtima Sabench. Department of Surgery and Anaesthesia, Hospital Sant Joan, Reus; Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus.

Román Turró. Gastrointestinal, Bariatric and Metabolic Endoscopy Unit, Gastroenterology Department, Centro Médico Teknon, Barcelona, and Hospital Quirón, Badalona.

Yamile Zabana. Gastroenterology Department, Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa, Terrassa; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD).