Infection by the SARS-COV-2 coronavirus causes mainly respiratory symptoms. However, it is also known to cause systemic involvement. Liver enzyme abnormalities have been reported in over half of hospitalised patients.1

Since the start of the pandemic, there have been several reported cases of patients developing secondary sclerosing cholangitis or post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy. This is a new condition which seems to be caused by factors already described in secondary sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill patients (SSC-CIP), but to which is also added the potential direct damage produced by SARS-COV-2 in the biliary epithelium. It is known that the virus can enter cells through the angiotensin-COnverting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, a receptor expressed in different cells of the human body, including cholangiocytes, so it is possible that there is a direct interaction between SARS-COV-2 and the biliary epithelium.2

The aim of this study was to analyse the development of cholangiopathy and subsequent sclerosing cholangitis in patients who required admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) due to SARS-COV-2 coronavirus infection in a particular health area.

Material and methodsIn this retrospective observational study, we included all patients admitted to the ICU of a health area in the Autonomous Region of Madrid from March 2020 to September 2021 with symptoms related to SARS-COV-2 infection and with positive PCR for the same. Patients with persistent changes in their liver function profile, predominantly cholestatic (understood as an increase in alkaline phosphatase [AP] >1.5 or gamma-glutamyl transferase [GGT] >3 times the upper limit of normal after transfer out of ICU) had a liver disease study performed, which included in all cases hepatotropic virus serology, hepatospecific immunity, immunoglobulins, liver Doppler and nuclear magnetic resonance cholangiography.

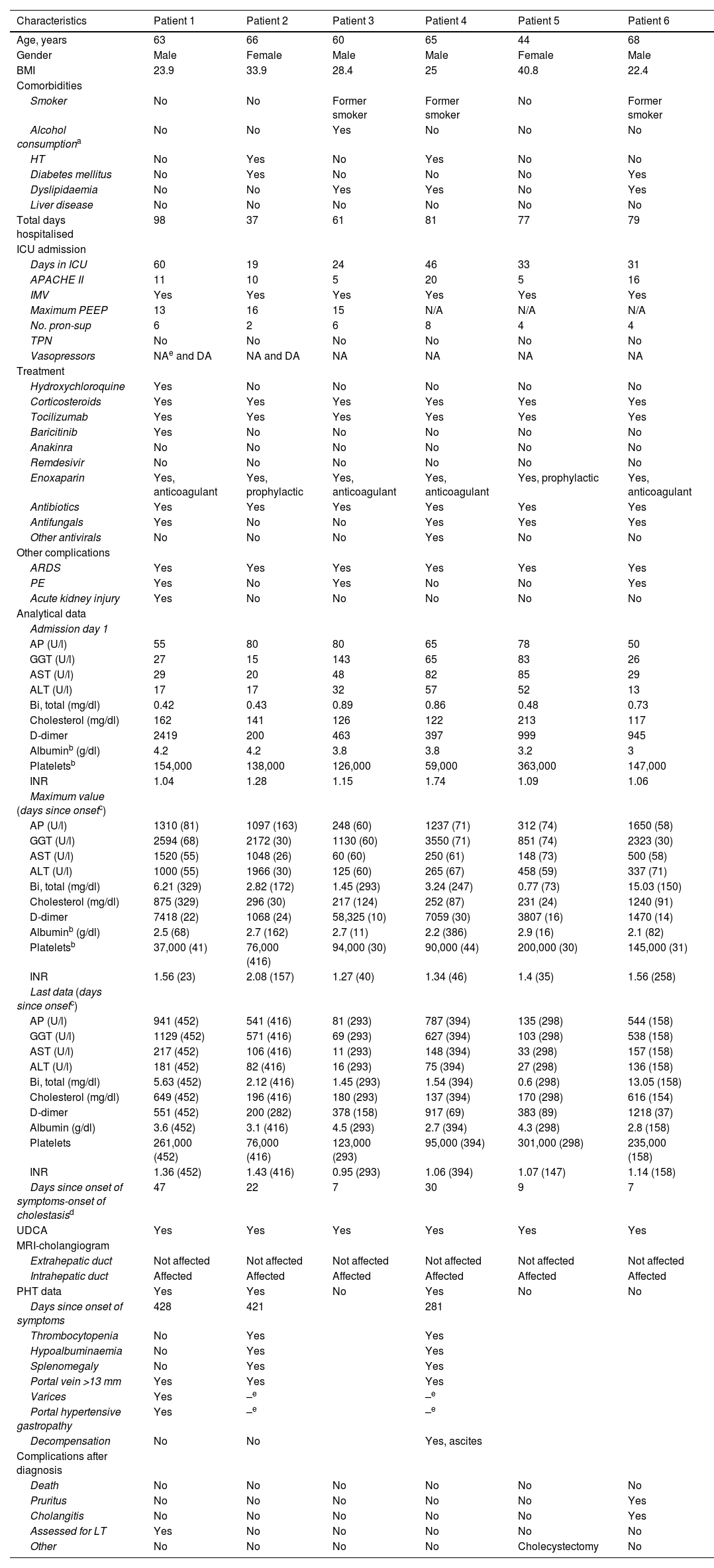

ResultsWe included 334 patients admitted to ICU during the study period. Of these, six cases of post-COVID cholangiopathy (1.8%) were identified, none of whom had a previous history of liver disease. The clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63 | 66 | 60 | 65 | 44 | 68 |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male | Male | Female | Male |

| BMI | 23.9 | 33.9 | 28.4 | 25 | 40.8 | 22.4 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Smoker | No | No | Former smoker | Former smoker | No | Former smoker |

| Alcohol consumptiona | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| HT | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Diabetes mellitus | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Dyslipidaemia | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Liver disease | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Total days hospitalised | 98 | 37 | 61 | 81 | 77 | 79 |

| ICU admission | ||||||

| Days in ICU | 60 | 19 | 24 | 46 | 33 | 31 |

| APACHE II | 11 | 10 | 5 | 20 | 5 | 16 |

| IMV | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Maximum PEEP | 13 | 16 | 15 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| No. pron-sup | 6 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| TPN | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Vasopressors | NAe and DA | NA and DA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Treatment | ||||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Corticosteroids | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Tocilizumab | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Baricitinib | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Anakinra | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Remdesivir | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Enoxaparin | Yes, anticoagulant | Yes, prophylactic | Yes, anticoagulant | Yes, anticoagulant | Yes, prophylactic | Yes, anticoagulant |

| Antibiotics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Antifungals | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Other antivirals | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Other complications | ||||||

| ARDS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PE | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Acute kidney injury | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Analytical data | ||||||

| Admission day 1 | ||||||

| AP (U/l) | 55 | 80 | 80 | 65 | 78 | 50 |

| GGT (U/l) | 27 | 15 | 143 | 65 | 83 | 26 |

| AST (U/l) | 29 | 20 | 48 | 82 | 85 | 29 |

| ALT (U/l) | 17 | 17 | 32 | 57 | 52 | 13 |

| Bi, total (mg/dl) | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.48 | 0.73 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 162 | 141 | 126 | 122 | 213 | 117 |

| D-dimer | 2419 | 200 | 463 | 397 | 999 | 945 |

| Albuminb (g/dl) | 4.2 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 3 |

| Plateletsb | 154,000 | 138,000 | 126,000 | 59,000 | 363,000 | 147,000 |

| INR | 1.04 | 1.28 | 1.15 | 1.74 | 1.09 | 1.06 |

| Maximum value (days since onsetc) | ||||||

| AP (U/l) | 1310 (81) | 1097 (163) | 248 (60) | 1237 (71) | 312 (74) | 1650 (58) |

| GGT (U/l) | 2594 (68) | 2172 (30) | 1130 (60) | 3550 (71) | 851 (74) | 2323 (30) |

| AST (U/l) | 1520 (55) | 1048 (26) | 60 (60) | 250 (61) | 148 (73) | 500 (58) |

| ALT (U/l) | 1000 (55) | 1966 (30) | 125 (60) | 265 (67) | 458 (59) | 337 (71) |

| Bi, total (mg/dl) | 6.21 (329) | 2.82 (172) | 1.45 (293) | 3.24 (247) | 0.77 (73) | 15.03 (150) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 875 (329) | 296 (30) | 217 (124) | 252 (87) | 231 (24) | 1240 (91) |

| D-dimer | 7418 (22) | 1068 (24) | 58,325 (10) | 7059 (30) | 3807 (16) | 1470 (14) |

| Albuminb (g/dl) | 2.5 (68) | 2.7 (162) | 2.7 (11) | 2.2 (386) | 2.9 (16) | 2.1 (82) |

| Plateletsb | 37,000 (41) | 76,000 (416) | 94,000 (30) | 90,000 (44) | 200,000 (30) | 145,000 (31) |

| INR | 1.56 (23) | 2.08 (157) | 1.27 (40) | 1.34 (46) | 1.4 (35) | 1.56 (258) |

| Last data (days since onsetc) | ||||||

| AP (U/l) | 941 (452) | 541 (416) | 81 (293) | 787 (394) | 135 (298) | 544 (158) |

| GGT (U/l) | 1129 (452) | 571 (416) | 69 (293) | 627 (394) | 103 (298) | 538 (158) |

| AST (U/l) | 217 (452) | 106 (416) | 11 (293) | 148 (394) | 33 (298) | 157 (158) |

| ALT (U/l) | 181 (452) | 82 (416) | 16 (293) | 75 (394) | 27 (298) | 136 (158) |

| Bi, total (mg/dl) | 5.63 (452) | 2.12 (416) | 1.45 (293) | 1.54 (394) | 0.6 (298) | 13.05 (158) |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 649 (452) | 196 (416) | 180 (293) | 137 (394) | 170 (298) | 616 (154) |

| D-dimer | 551 (452) | 200 (282) | 378 (158) | 917 (69) | 383 (89) | 1218 (37) |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.6 (452) | 3.1 (416) | 4.5 (293) | 2.7 (394) | 4.3 (298) | 2.8 (158) |

| Platelets | 261,000 (452) | 76,000 (416) | 123,000 (293) | 95,000 (394) | 301,000 (298) | 235,000 (158) |

| INR | 1.36 (452) | 1.43 (416) | 0.95 (293) | 1.06 (394) | 1.07 (147) | 1.14 (158) |

| Days since onset of symptoms-onset of cholestasisd | 47 | 22 | 7 | 30 | 9 | 7 |

| UDCA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| MRI-cholangiogram | ||||||

| Extrahepatic duct | Not affected | Not affected | Not affected | Not affected | Not affected | Not affected |

| Intrahepatic duct | Affected | Affected | Affected | Affected | Affected | Affected |

| PHT data | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Days since onset of symptoms | 428 | 421 | 281 | |||

| Thrombocytopenia | No | Yes | Yes | |||

| Hypoalbuminaemia | No | Yes | Yes | |||

| Splenomegaly | No | Yes | Yes | |||

| Portal vein >13 mm | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Varices | Yes | –e | –e | |||

| Portal hypertensive gastropathy | Yes | –e | –e | |||

| Decompensation | No | No | Yes, ascites | |||

| Complications after diagnosis | ||||||

| Death | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Pruritus | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Cholangitis | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Assessed for LT | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Other | No | No | No | No | Cholecystectomy | No |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AP: alkaline phosphatase; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; Bi, total: total bilirubin; BMI: body mass index; DA: dopamine; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; HT: hypertension; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; INR: international normalised ratio; LT: liver transplantation; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NA: noradrenaline; N/A: not applicable; No. pron-sup: number of prone-supine positioning cycles; PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure; PE: pulmonary embolism; PHT: portal hypertension; TPN: total parenteral nutrition; UDCA: ursodeoxycholic acid.

Four men and two women were diagnosed with a mean age of 61 ± 8.8 years: 66% with a body mass index >25; none active smokers; and five without abusive consumption of alcohol (>4 standard drink units per day [>2 in women]).

All of them (100%) developed acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, vasoactive drugs (noradrenaline, dopamine), enoxaparin and prone-supine positioning cycles (range 2–8). The mean stay in ICU was 35.5 days. At least 50% required high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP >10).

In all cases, intrahepatic bile duct abnormalities were identified on magnetic resonance cholangiography. All had multiple short strictures and small saccular dilations without images suggestive of lithiasis. No abnormalities were found in the extrahepatic bile duct.

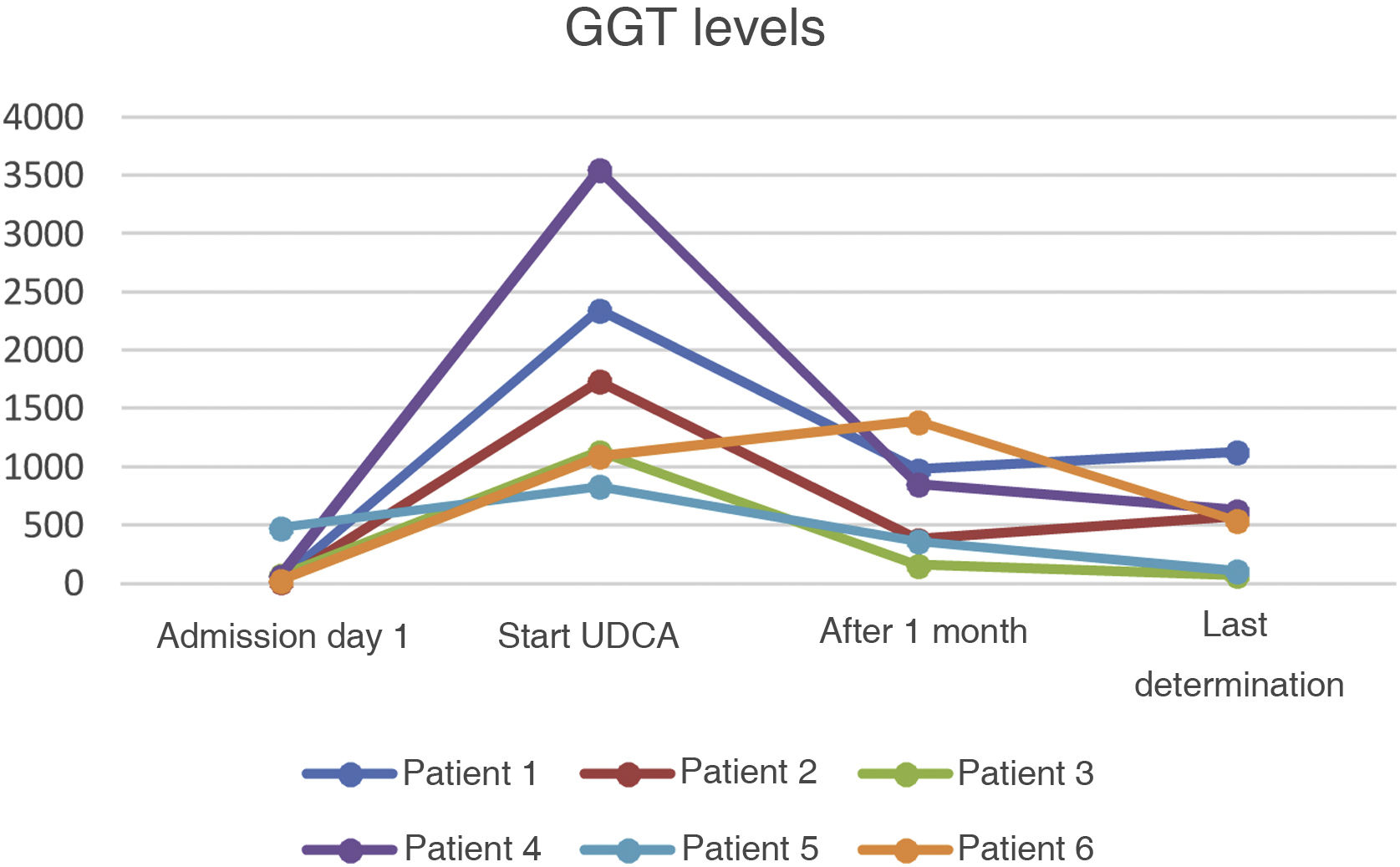

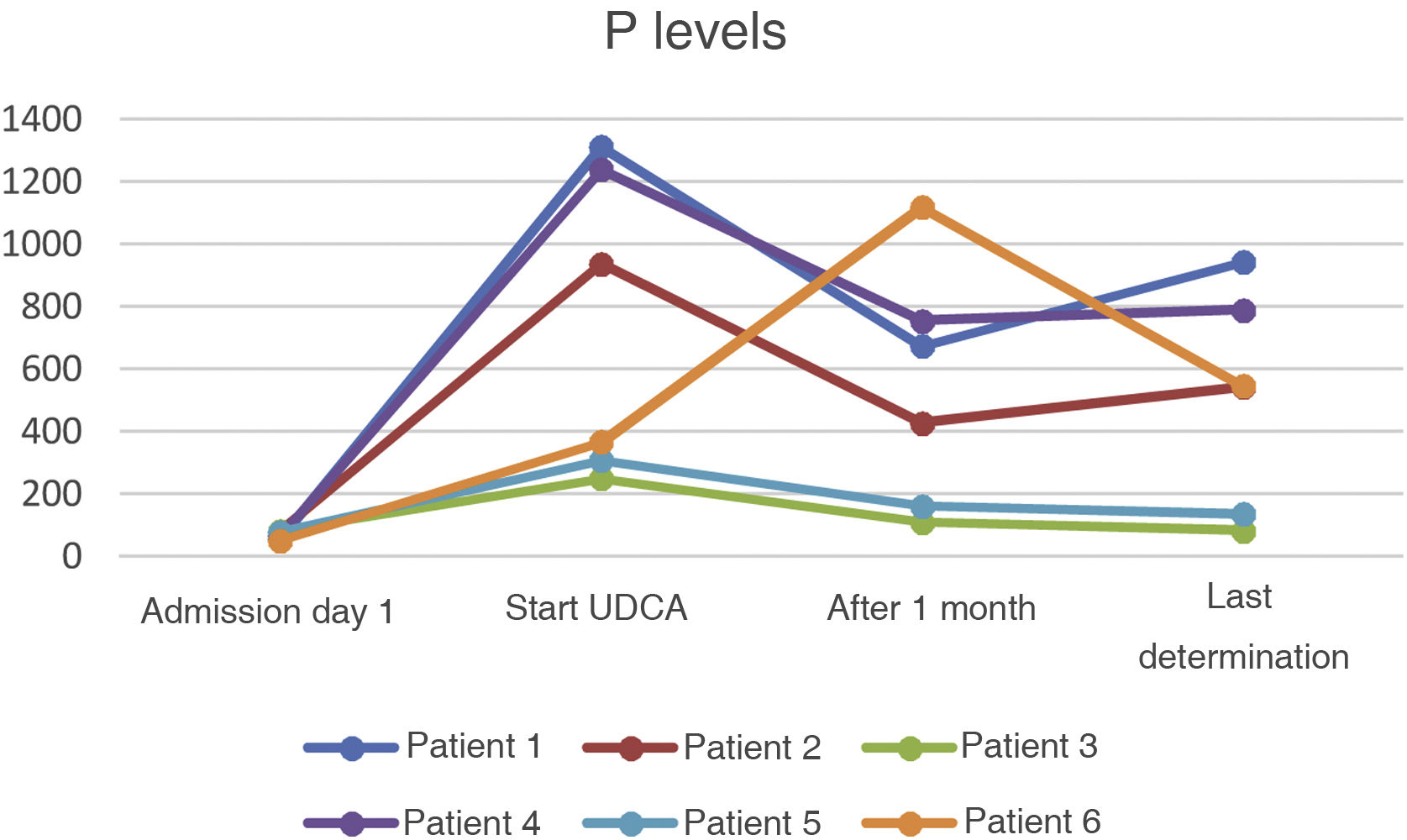

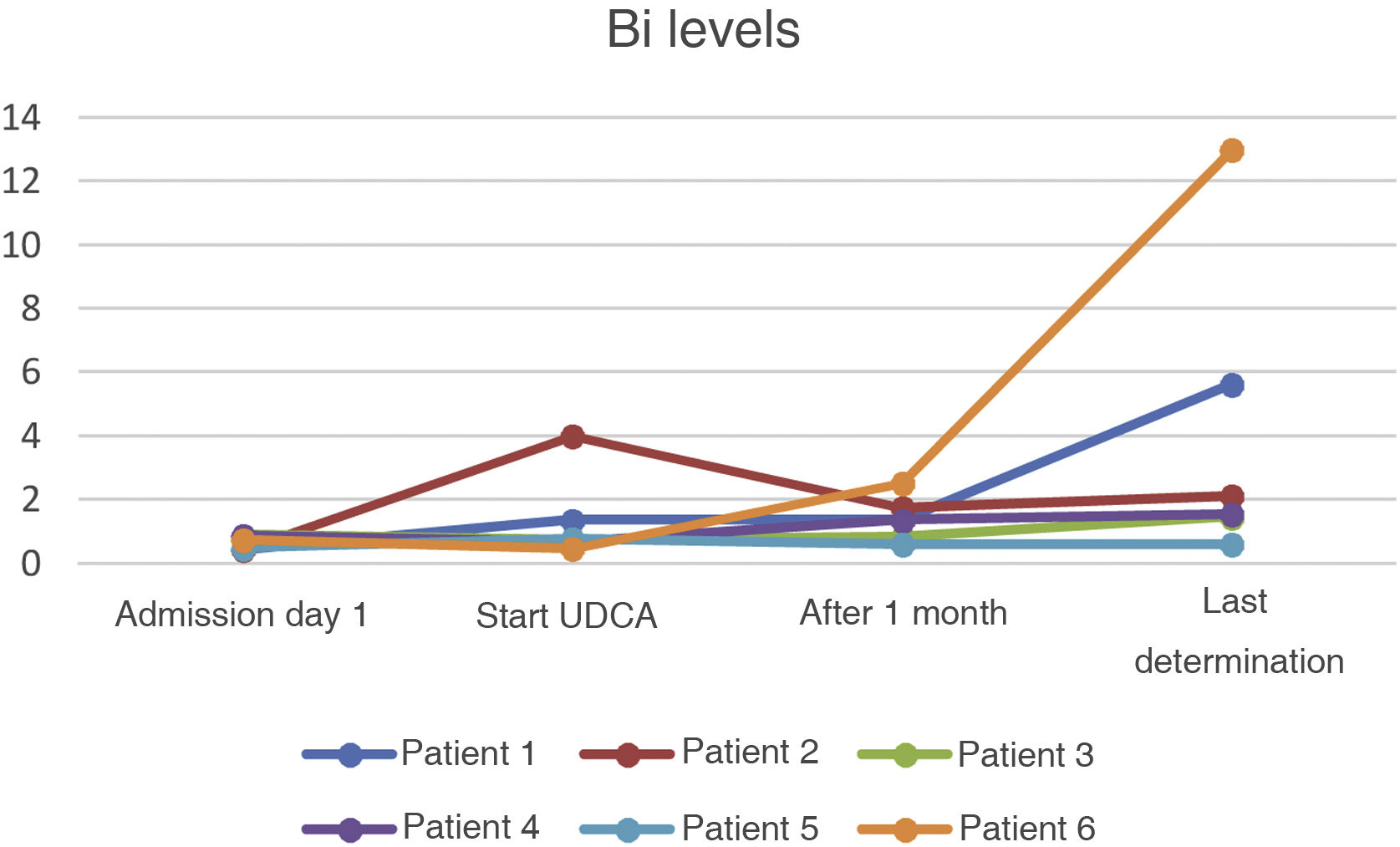

All six patients were prescribed ursodeoxycholic acid at doses of 10−15 mg/kg, with a decrease in cholestasis enzymes (GGT and AP) in all cases but no simultaneous decrease in bilirubin (Bi) values (Figs. 1–3).

After a follow-up period of a median of 282 days (range 89–452), none of the patients' liver function profiles have completely returned to normal and three have developed signs of portal hypertension. In patient 2, liver stiffness was measured as 38 kPa (F4) with FibroScan® (402, Echosens) during her follow-up. None of the patients in the sample had a liver biopsy.

All six cases developed hypercholesterolaemia during admission, even the previously non-dyslipidaemic patients. Due to resistance to other lipid-lowering agents, patients 1 and 6 had to be started on treatment with alirocumab, a monoclonal antibody which binds to the PCSK9 protein, and these were the cases showing the greatest deterioration in liver function, with bilirubin levels remaining >5 mg/dl at the last follow-up.

Once discharged, three patients had to be readmitted. Patient 4 developed a pleural empyema and his first decompensation in the form of ascites was diagnosed in this context. Patient 5 consulted with repeated pain in the right hypochondriac region, for which she underwent cholecystectomy on suspicion of biliary colic. Patient 6 was admitted for a first episode of acute cholangitis without choledocholithiasis, requiring treatment with antibiotics. None of the patients have died during follow-up. At the time of writing, one of the patients is in the process of being assessed for a liver transplant at a tertiary hospital.

DiscussionSecondary sclerosing cholangitis encompasses a group of chronic cholestatic diseases which affect the intra- or extrahepatic bile duct with the risk of evolving into cirrhosis. In the case of SSC-CIP, the development of advanced fibrosis seems to be particularly rapid compared to other aetiologies.3 In our sample we found progression to portal hypertension in 50% of the patients within a range of 281–428 days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

It is a rare condition, rarely described in the literature, with an estimated prevalence of 0.05% of patients admitted to ICU.4 In our sample, post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy had an accumulated incidence of 1.8%. In other case series of post-COVID-19 cholangiopathy, the incidences calculated were 0.59%,5 2.6%1 and 12%6; combined with our report, this suggests that there may be an added aetiological factor as well as the factors already known in the development of sclerosing cholangitis in the critically ill patient. It is likely that the direct damage of SARS-COV-2 on cholangiocytes when interacting with receptors such as ACE2, the development of microthrombi in the biliary tree vascularisation in relation to the state of hypercoagulability that occurs during infection with COVID-19, and the magnitude of the inflammatory cascade generated in these patients are all factors to be added to the equation.5

However, we also have to consider that all six patients required the use of vasoactive drugs and mechanical ventilation with high PEEP, both of which can increase the risk of developing ischaemic cholangiopathy,7 and they all received potentially hepatotoxic drugs.

In our sample, all the patients were started on treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid, leading to an improvement in GGT values and, to a lesser extent, in AP during follow-up. However, there has been no parallel decrease in bilirubin values. Further studies are needed in this area, as evidence on the benefits of the drug in patients with SSC-CIP is not entirely clear. Our results could have been affected by events in the course of the disorder itself which, having only recently been described, is still not fully understood.

In any event, we believe that new prospective studies are necessary to determine the pathophysiology, prevention and treatment of this new condition, which carries the potential risk of progressive liver damage.

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

To Dr Santos Arrontes, for his help in reviewing this manuscript.