Despite previous research demonstrating the importance of entrepreneurial leadership in fostering innovative behavior among employees, less is known about the mechanisms and processes through which leaders influence their employees’ innovative behavior. By utilizing social cognitive theory, the purpose of this paper is to examine the sequential role of innovation climate and employees’ intellectual agility in mediating the link between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ innovative behavior. We collected 241 data points from full-time employees in the US using the survey method and tested our hypotheses using hierarchical multiple regression and PROCESS Macro. Entrepreneurial leadership was found to significantly impact employees’ innovative behavior through the innovation climate and their intellectual agility. These findings allow leaders to pinpoint their critical roles in fostering innovation in their businesses and establishing the ideal culture and climate for innovation. It also allows leaders to create innovative settings to encourage employees to share ideas and concepts in a confident manner. A discussion of the findings, implications, limitations, and future research avenues is included.

As an organization looks to succeed in an ambiguous, competitive environment, entrepreneurial behaviors are crucial to supporting inventiveness, adaptation, and innovation (Anderson et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Pidduck et al., 2021). García-Vidal et al. (2019) claim that organizations that want to succeed in today's rapidly changing business environment cannot rely on outdated management theories and that effective leadership is one of the primary drivers for effective change. There is ample evidence that leaders can influence employee outcomes in significant ways (Althnayan et al., 2022; Bajaba et al., 2021, 2022a; Basahal et al., 2022; Fuller et al., 2022). In addition, as the corporate environment has become increasingly hostile and turbulent, a new type of leadership is required, known as entrepreneurial leadership (EL), which differs from traditional managerial leadership in that it emphasizes those attributes and behaviors of a leader that may contribute to entrepreneurial behaviors, such as recognizing and exploiting opportunities (Renko et al., 2015). The importance of EL has been growing in recent years as businesses strive for increased performance, adaptability, and sustainability (Gupta et al., 2004; Subramaniam & Shankar, 2020).

Since the early 1990s, the body of knowledge in EL has increased significantly. Recent studies by Arshi & Burns (2018) and Hughes et al. (2018) have called for scholars to explore mediating factors concurrently for a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of how leaders influence employees’ innovative behavior (EIB). Moreover, because there has been so little empirical research investigating the relationship between EL and EIB (Bagheri et al., 2020), our understanding of the mechanisms and processes through which entrepreneurial leaders can affect EIB requires a higher level of theoretical precision (Lee et al., 2020).

In addition, there is growing support for the idea that innovative employee behavior is what drives continuous innovation (Zhang & Yang, 2020). Consequently, research into employee innovative behavior has become mainstream over the past years (e.g., Akbari et al., 2021; Bagheri et al., 2020). Nevertheless, these studies have primarily been focused on transformational leadership (e.g., Amankwaa et al., 2019; Afsar & Masood, 2018). Other recent studies have also been conducted on the other newer genre of leadership styles, such as ethical, authentic, and servant leadership styles. For example, Rego et al. (2014) focused on authentic leadership, Javed et al. (2017) on ethical leadership, and Wang et al. (2019) on servant leadership. Throughout this study, we argue that in order to gain a competitive advantage and achieve organizational success through innovation within a dynamic and complex work environment, leaders must assist subordinates in identifying and seizing entrepreneurial opportunities.

Additionally, to our knowledge, no research has been published in the literature addressing the relationship between EL and employees’ intellectual agility (EIA) when it comes to identifying entrepreneurial opportunities. Further, researchers have demonstrated that employees’ innovative behavior is improved by creating a conducive innovation climate (IC) that encourages receptivity to new ideas and increases their willingness to pursue them (Li et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2013). Despite the fact that it has been demonstrated in previous studies (Akbari et al., 2021) that there is a relationship between EL and EIB, more research is still needed in order to unravel the mechanism in which EL affects EIB.

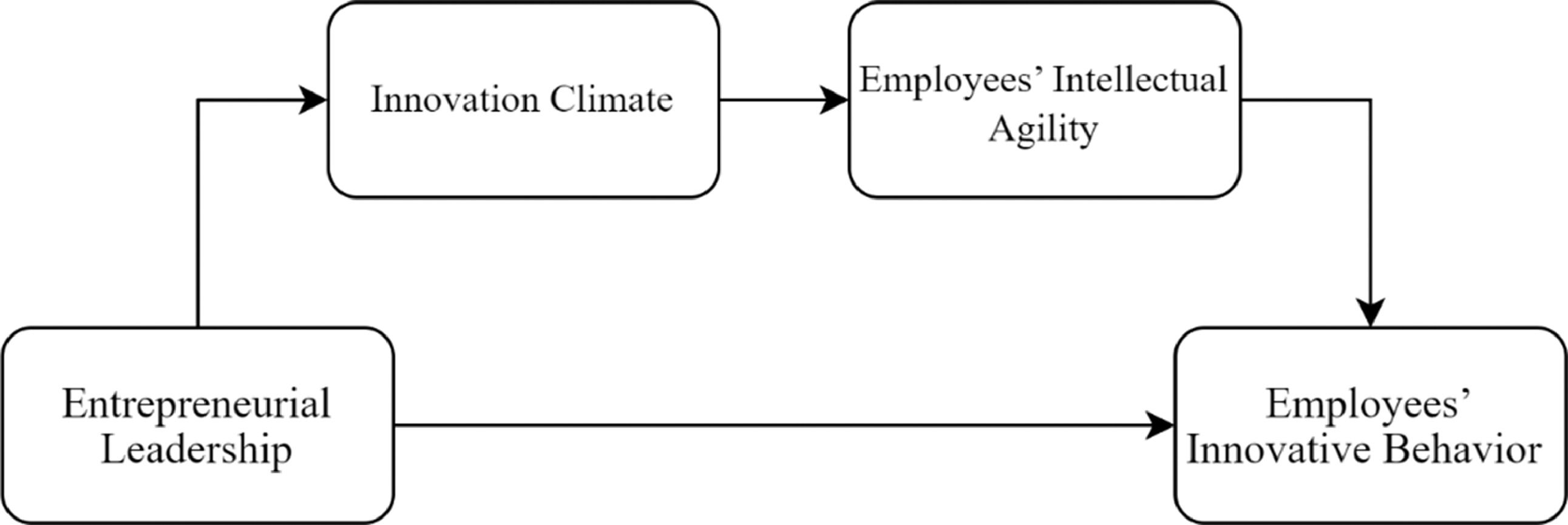

On that basis, the aim of this study is to develop a conceptual model that sheds light on how EL can foster innovative behavior and examine the mediating roles that IC and EIA play in this relationship by analyzing a sample consisting of 241 full-time employees in the US. Our work addresses several gaps in the existing literature. Firstly, this study aims to fill a gap in the empirical evidence regarding EL's importance in encouraging employee innovation by thoroughly investigating the mediating mechanism of IC and EIA (see Fig. 1). Second, this study will also contribute to a more robust and nuanced understanding of the relationship between EL and EIB by incorporating social cognitive theory (SCT).

This research is organized into four sections. The following section provides an overview of the literature on the full spectrum of theories and concepts that support the proposed model. The next section discusses the study's methodology, sample, and measurement scales. The penultimate section introduces the quantitative results, including the fit of the model and hypotheses testing results. The final section discusses the implications, limitations, and directions for further research.

Theoretical background and hypotheses developmentThe social cognitive theoryIn our attempt to address this research gap, we develop a research model through the lens of social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) to answer researchers’ demands to explain how entrepreneurial leaders affect EIB by specifically investigating the mediating role of IC and EIA. The social cognitive theory provides a framework for understanding, predicting, and changing human behavior. In SCT, the interaction between the individual and behavior is influenced by the individual's thoughts, actions, and interpretations. Furthermore, the interaction between an individual and the environment tends to involve the development and modification of cognitive abilities and human beliefs by societal factors and environmental structures. The final interaction is between the environment and behavior and is comprised of an individual's behavior influencing the characteristics of their environment, which in turn affects their behavior (Bandura, 2005). This enables us to examine the IC and intellectual agility of employees as motivational and affective mechanisms that have been recognized as crucial pathways connecting leadership to innovative behavior in the workplace (Hughes et al., 2018). Several studies have already explored the impact of EL on employees’ outcomes through the use of the STC by empirically examining a number of outcomes, such as innovative work behavior (Bagheri, Akbari and Artang, 2022; Bagheri et al., 2020; Cai et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Newman et al., 2020). This study has therefore extended previous literature in that it proposes that the EL has a functional role as an external determinant to support innovation in the workplace and that this relationship is mediated by the IC and EIA.

Entrepreneurial leadership and innovation climateEL has arisen as a distinctive form of leadership for economic growth (Park et al., 2014). Innovative organizations often require entrepreneurial leaders who can effectively utilize resources and inspire followers’ inventiveness through their vision. EL has been identified by Renko et al. (2015) as a style of leadership that comprises the attributes to motivate and lead the members of the group for the identification and exploitation of entrepreneurial initiatives to attain organizational objectives. Entrepreneurial leaders play a dual role, including encouraging their followers to be highly innovative and behaving as role models for their followers (Gupta et al., 2004). Therefore, the leaders of any business play a crucial role in developing and influencing the business environment that results in favorable behavioral patterns.

Additionally, the innovation climate supports employee creativity and innovative behavior, as well as the effort to explore and apply new ideas throughout the business (Ali & Park, 2016; Wang et al., 2013; Park & Jo, 2017). Climate for innovation can be described as a combination of employee perceptions around an organization's environment that supports risk-taking behavior, allots sufficient resources, and promotes a competitive environment that fosters innovation at work (Scott & Bruce, 1994). Moreover, Kang et al. (2015) argued that there is a positive relationship between EL behavior and a firm's innovative climate, which has a situational effect on employees’ behavior in the workplace, endorses employees’ innovative challenges, and prevents them from being responsive. Consequently, entrepreneurial leaders create a favorable climate for innovation, which not only empowers but also stimulates their subordinates to be innovative and discover innovative solutions to workplace challenges (Mehmood et al., 2019).

Drawing on social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986, 2014), we examine IC as an effective and motivational mechanism that explains how EL promotes EIBs. To lead innovation, a leader must create an environment that encourages all employees to engage in innovative practices and generate and exploit new ideas. (Jaiswal & Dhar, 2015). A study by Li et al. (2020) found that entrepreneurial leadership is positively correlated with an organization's innovative environment. In their view, entrepreneurial leaders foster an environment that encourages their members to think differently, generate new ideas, and find innovative solutions to problems. According to this study, entrepreneurs may intentionally influence their employees’ innovative behavior by creating a culture where they can develop new ideas and achieve them without feeling intimidated. Therefore, EL creates a conducive environment for employees to be innovative. Consequently, the leaders of any business play a crucial role in developing and influencing the business's climate, which stimulates favorable behaviors (Reise & Waller, 2009). Based on the above arguments, it is reasonable to hypothesize:

H1: Entrepreneurial leadership will be positively related to the innovation climate.

Extensive research demonstrates the significance of the innovation climate in encouraging individuals to think differently, hence enhancing their innovative behaviors (Zhang et al., 2018; Waheed et al., 2019). In addition, intellectual agility is a relatively new aspect of human capital that contributes to the innovativeness of businesses. Intellectual agility relates to the capability of employees to adjust their patterns of thinking, seek out new knowledge, and generate unique solutions to current and future challenges (Tierney & Farmer, 2002). In addition, a climate that fosters innovation cultivates the innovative skills of employees, thus fostering innovation inside a business (Shanker et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018; Waheed et al., 2019). IC is a vital contextual component for innovative behavior throughout the innovation process, particularly during the idea execution phase (Ren & Zhang, 2015); shared perception between employees that their effort is valued by the business would increase their willingness to cooperate and establish a climate that promotes innovation (Chen et al., 2013). Innovation can be boosted by fostering an innovation-friendly environment throughout the organization and removing hurdles that inhibit innovation activities (Ren & Zhang, 2015).

In addition, one of the interactions in social cognitive theory proposes that individuals acquire and use knowledge from their business environment before deciding how to behave. As a result, a promising innovative climate produced by entrepreneurial leaders not just allows but also inspires their subordinates to be innovative and develop novel and innovative solutions to business challenges (Javed et al., 2019; Sethibe & Steyn, 2017). Entrepreneurial leaders not just challenge the current system and generate fresh creative ideas and innovative solutions, but they also inspire risk-taking behaviors and foster an environment conducive to innovation. While leaders are responsible for building an organizational climate conducive to innovation, individuals’ knowledge, abilities, passion for innovation, and intellectual agility frequently support innovation behavior (Newman et al., 2020). It was found by Kang et al. (2016), for example, that team innovation climate enhanced an employee's passion for inventing and that as proactive (risk-taking) culture increased, the link between innovative climate and employee passion for inventing (employee innovation) strengthened. Magni et al. (2018) showed that team innovation climate enhanced proactive and risk-taking attitudes and, therefore, improvisation. In Shaw et al. (2012), two aspects of the team climate (participative safety and vision) were found to be positively correlated with staff competency. The perception of organizational innovation climate has been strongly linked to employees’ innovation behaviors, which we argue is due to their intellectual agility (Park & Jo, 2017; Ren & Zhang, 2015; Yu et al., 2013). Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Innovation climate will be positively related to employees’ intellectual agility.

Success and survival in a progressively knowledge-driven society are reliant on the ability to participate in the exploration, experimentation, and creation of new inventions, product lines, manufacturing processes, knowledge transfer, and corporate structures (Dabić et al., 2018, Vlajčić et al., 2019, Manesh et al., 2020). These capabilities, also known as innovativeness, are regarded as vital assets that connect businesses’ embedded innovation capabilities with the outcomes of the innovation process (Santos-Rodrigues et al., 2010). Innovativeness exists as an intangible asset inside the expertise of human organizational capital. The development of employees’ intellectual capabilities allows businesses to translate knowledge into new product lines, services, or procedures that the market demands (Demartini & Beretta, 2020). Agyapong et al. (2017) examined the associations between social capital, performance, and innovation in developing economies. This study discovered that social capital has a positive effect on performance, implying that having more social capital is likely to increase corporate performance.

Furthermore, the early literature on knowledge management acknowledged the significance of an environment that maximizes employee innovation and effort. For instance, Bontis et al. (2002) found that employees’ perceptions of the value of their suggestions to management and the organization offer a significant motivator for employee initiatives in the areas of enhancing knowledge and skills, fostering self-confidence and skill, developing interest and motivation for tackling challenges, and moving potential barriers forward. In addition, numerous empirical studies have demonstrated that the capacity to convert and exploit information enhances innovative capabilities and organizational success (Caseiro & Coelho, 2019, Santos-Rodrigues et al., 2010). Therefore, increasing innovation agility has a favorable effect on organizational innovation.

From an SCT perspective, we suggest that, while managers are responsible for fostering an environment conducive to innovation, employees’ intellectual agility and abilities typically contribute to innovation's success (Dabić et al., 2021; Santos-Rodrigues et al., 2010). Intellect agility boils down to learning about the challenges companies face and then putting this knowledge into action within a business and adapting the skills and expertise of that business to meet the demands of a dynamic environment. For example, Choudhary et al.(2020) empirically investigate how human capital investments manifest at the individual level to determine when and how micro-social orders emerge when organizations invest in their employees. Consequently, employees feel grateful to their organizations for the resources they receive in the form of new knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (KSAOs). After acquiring the resources, employees are encouraged to share them with peers and colleagues, leading to knowledge management behaviors. As a result of participating in firm-specific knowledge management behaviors, employees are encouraged to develop, promote, and implement novel ideas and procedures, thus enhancing their innovation ability. We, therefore, propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Employees’ intellectual agility will be positively related to employees’ innovative behavior.

Literature asserts that EL is a significant factor in fostering and enhancing the innovative behavior of employees in a competitive corporate environment. Recently, Researchers in management have constantly acknowledged EL as a style of people-oriented leadership (Newman et al., 2018) as well as Gupta et al. (2004), Miao et al. (2018), and Renko et al. (2015) stressed its significance. Afsar & Masood (2018) believe that EIB is a motivational and cognitive procedure aimed at presenting, generating, and implementing innovative solutions (Scott & Bruce, 1994) to deliver original and beneficial solutions to complex and inadequately defined challenges (Zhang & Bartol, 2010). In addition, existing literature acknowledges the influence of leadership on individual actions and attitudes, particularly innovative employee behavior (De Jong & Den Hartog, 2007; Cai et al., 2019; Khaola & Coldwell, 2018).

In this sense, leaders serve as a source of authority and a crucial aspect that influences the innovative behavior of employees (Yukl, 2013). Accordingly, the nature of leader-employee relationships and engagements relates to the generation and implementation of innovative initiatives (De Jong & Den Hartog, 2007). Entrepreneurial leaders cultivate an attractive and encouraging in which all employees are motivated to recognize innovation as one of their core responsibilities and to be resilient in the face of the inherent challenges experienced by innovation activities (Karol, 2015). Bagheri (2017) found that EL has a strong effect on fostering innovative employee behavior. In the healthcare sector, Bagheri & Akbari (2018) confirmed that EL has a significant impact on developing the innovative behavior of nurses in hospitals. Newman et al. (2018) revealed that leaders who apply the EL approach to their task performance significantly foster innovative behavior within their subordinates. In sum, an entrepreneurial leader may effectively direct the innovation activities by promoting the generation and implementation of novel ideas by their employees.

Through the lens of social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986, 1988), we suggest that entrepreneurial leaders encourage and empower their employees to recognize and utilize entrepreneurial opportunities in the workplace (i.e., innovate) and behave entrepreneurially. In the current study, we apply this notion to conceptualize EL as a technique in which leaders not only encourage and support entrepreneurial conduct in subordinates but also serve as role models by exhibiting entrepreneurial behavior personally. On the basis of these theoretical foundations, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: Entrepreneurial leadership will be positively related to employees’ innovative behavior.

Considering the previous discussions and hypotheses, we suggest a sequential mediation model linking EL and employees’ innovative behavior. Specifically, we offer that EL relates to improving the IC, which, in turn, may produce greater EIA and, ultimately, promotes employees’ innovative behavior. This mediation chain is in line with social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1988) as the innovative climate established by the entrepreneurial leaders can be used as a positive stimulation that enhances the willingness of employees to adopt innovative entrepreneurial activities and provide employees with resources by integrating a wide range of tools from various sources in order to develop systematic cognitions and innovative mindsets. Additionally, EIA can be effectively expressed in this positive IC, which helps produce more innovative behavior. Thus, we further assume that the contingent function of an innovative climate in the intellectual agility-building process of employees results in a sequential mediation model. In conclusion, leaders and employees who understand an innovative firm's climate are shown to be highly empowered, leverage their intellectual capabilities to thrive in a complex and dynamic business climate, and behave innovatively (Bos-Nehles & Veenendaal, 2019; Mokhber et al., 2018). Taken together with all of the arguments, we propose the following hypotheses:

H5: The innovation climate will mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ intellectual agility.

H6: Employees’ intellectual agility will mediate the relationship between innovation climate and employees’ innovative behavior.

H7: Innovation climate and employees’ intellectual agility will sequentially mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ innovative behavior.

Online questionnaires were used as the primary data collection tool. The online questionnaire gauges participants’ perceptions based on different literature scales on how EL encourages EIB and the mediated association by EIA, which is a personal determinant, and how this mediated relation strength depends on the innovation climate.

Participants were full-time employees in a variety of industries (e.g., sales, finance, and technology) and occupations; they were recruited and paid through Pollfish, an online crowdsourcing platform that allows researchers to control who participates in a study and monitor dropout rates and completion times (Litman et al., 2017). Pollfish also makes it possible to include eligible participants from a broad range of jobs, people, and geographic locations.

Researchers have used Pollfish's platform for recruiting and delivering surveys and obtaining reliable and valid data (Akiba et al., 2021). Pollfish, workers tend to read survey instructions carefully, and the samples have diversity in terms of age, education, and work experience, providing high-quality data comparable to those from other data sources (Ukpabi et al., 2021; Ionescu, 2020). We also ensured that the survey was designed and formatted in an efficient manner in order to avoid receiving poor data when using the digital platform, as noted by Lovett et al. (2018). We required respondents to be full-time employed adults aged 18 and older working in the US and a minimum of 6 months of work experience with the current leader because we wanted to ensure that the employees have spent enough time with their current leader to evaluate their leadership style. In order to increase the data quality, we added one question to examine the data with insufficient-attention checks, which is, please answer strongly disagree with this question. By adding this attention check, Pollfish eliminated all participants who failed to choose that particular answer. However, we took the precaution of following several procedures to control the data quality (Cheung et al., 2017; DeSimone et al., 2015).

Because the sample was drawn from a high-reliability source (Pollfish), very few low-quality data were encountered to be eliminated. However, following the listwise deletion procedure outlined by Hair et al. (2018), a total of 241 usable questionnaires were used in the analysis due to the removal of data from participants answering too many consecutive questions with the same response, completing surveys four times faster than the average respondent, answering attention-check questions incorrectly, and/or did not meet the minimum condition of 6 months of work tenure. The sample size adheres to the recommended ratio of 15 observations per independent variable and the preferred sample size of 90 observations to run the analysis in this study, as suggested by Hair et al. (2018). The final sample consisted of 55% male and 45% female. The mean age group of the participants was 3, representing the age group between 35 and 44 years old. Among the participants, 46% had university degrees, and 33% had a graduate degree. Table 1 includes the demographic information of the sample.

MeasuresAll measures used in this study were derived from the literature and had high Cronbach's α scores, as presented in Table 2. A five-point Likert-type scale was employed for participants to respond to. Entrepreneurial leadership was measured using an 8-item scale (α = 0.91) developed by Renko et al. (2015). A sample item is “Comes up with radical improvement ideas for the products/services we are selling.” Entrepreneurial leadership was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). Innovation climate was measured using a 16-item scale (α = 0.80) developed by Scott & Bruce (1994). A sample item is “Creativity is encouraged here.” Innovation climate was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Employees’ intellectual agility was measured using a 15-item scale (α = 0.84) developed by Alavi et al. (2014). A sample item is “I look for the opportunities to make improvements at work.” Employees’ intellectual agility was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). Finally, employees’ innovative behavior was measured using a 6-item scale (α = 0.88) developed by Hu et al. (2009). A sample item is “At work, I come up with innovative and creative notions.” Employees’ innovative behavior was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). For more information about the constructs, see Appendix 1.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliabilities, (N = 241).

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1- EL | 3.43 | .90 | (.91) | .43⁎⁎ | .56⁎⁎⁎⁎ | .58⁎⁎ | -.17 | -.22⁎⁎ | .22⁎⁎ |

| 2- EIA | 3.96 | .52 | .44⁎⁎ | (.84) | .52** | .53⁎⁎ | -.14 | -.02 | .12 |

| 3- IC | 3.46 | .56 | .57⁎⁎ | .53⁎⁎ | (.80) | .53⁎⁎ | -.23⁎⁎ | -.16 | .21 |

| 4- EIB | 3.54 | .85 | .58⁎⁎ | .53⁎⁎ | .53⁎⁎ | (.88) | -.30⁎⁎ | -.22⁎⁎ | .31⁎⁎ |

| 5- Gender | .45 | .49 | -.17⁎⁎ | -.12 | -.22⁎⁎ | -.29⁎⁎ | - | .10 | -.14 |

| 6- Age | 3 | 1.04 | -.22⁎⁎ | -.02 | -.15* | -.22⁎⁎ | .10 | - | .11 |

| 7- Education | 2.12 | .73 | .22⁎⁎ | .13* | .21⁎⁎ | .32⁎⁎ | -.13* | .12 | - |

Note. M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation; Boldfaced diagonal elements are reliabilities (Cronbach's Alpha); Gender: 0 = Male, 1 = Female; Age: 1= 18 - 24 years, 2= 25 - 34 years, 3= 35 - 44 years, 4= 45 - 54 years, 5= “54+ years; Education: 1= high school, 2= college degree, 3= graduate degree; EL= Entrepreneurial leadership; IC = Innovation climate; EIA = Employees’ intellectual agility; EIB = Employees’ innovative behavior. Below the diagonal elements are the correlations between the constructs. Above the diagonal elements are the correlations between the constructs after controlling the marker variable.

In terms of control variables, existing literature suggests that some individual and organizational characteristics may affect the relationship between independent and dependent variables and thus need to be controlled to achieve an adulteration-free relationship between observed variables (Delery & Doty, 1996; Liu & Almor, 2016). Thus, in this research, we controlled for three demographic variables: gender, age, and education. Gender was dummy coded (0= “male” and 1= “female”). Age was measured using five categories (1= “18 - 24 years” to 5= “54+ years”). Finally, education was measured using three categories (1= “high school,” 2= “college degree,” 3= “graduate degree”).

AnalysisHierarchical multiple regression analysis was used to assess the direct effect on entrepreneurial leadership, innovation climate, employees’ intellectual agility, and employees’ innovative behavior. To evaluate the mediation effect, a test was conducted via the PROCESS macro (v4.1) using SPSS 28 software with the bootstrap sampling method (sample size = 5000), as recommended by Hayes (2013) and used by several scholars (Bajaba et al., 2022b; Naqshbandi & Jasimuddin, 2022; Salam & Bajaba, 2021). The bootstrap sampling method generated asymmetric confidence intervals (CIs) for the mediating effect.

ResultsDescriptive statistics and correlation analysisThe descriptive statistics, reliabilities, and zero-order correlations are presented in Table 2. All correlations related to the hypothesized paths were statistically significant at p = .001. Entrepreneurial leadership was found to be positively correlated with innovation climate (r = 0.56, p < 0.01), employees’ intellectual agility (r = 0.43, p < 0.01), and employees’ innovative behavior (r = 0.57, p < 0.01). Similarly, innovation climate was positively correlated with employees’ intellectual agility (r =0.52, p < 0.01) and employees’ innovative behavior (r = 0.53, p < 0.01), respectively. Lastly, employees’ intellectual agility was positively correlated with employees’ innovative behavior (r = 0.53, p < 0.01). The reliability was evaluated by calculating the internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach's alpha). All internal consistency reliabilities of the variables in the study were sufficient for research purposes (above 0.70; Hair et al., 2018). The Cronbach's alpha coefficients of entrepreneurial leadership, innovation climate, employees’ intellectual agility, and employees’ innovative behavior were 0.91, 0.80, 0.84, and 0.88, respectively.

Common method bias analysisAs all indicators were self-reported, the impact of Common Method Bias (CMB) should be analyzed in order to deal with the potential presence of common method bias. To ensure that CMB is eliminated or minimized, established recommendations were followed (Podsakoff et al., 2003). This study employed the correlational marker technique by Lindell & Whitney (2001) for controlling method variance using a marker variable that is theoretically irrelevant to substantive variables in the research (Williams et al., 2010). The partial correlation measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two continuous variables and compares the variations while controlling for the marker variable chosen (Lindell & Whitney, 2001). This research used one of the most updated social science research marker variables: the attitude toward the Color Blue. This marker variable was measured using a 7-item scale (α = 0. 94) developed by Miller & Simmering (2022). A sample item is “Blue is a beautiful color.” The marker variable was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Results indicated that partialling-out technique variance in this fashion did not affect the original correlation among substantive variables or change its statistical significance, as shown above, the diagonal in Table 2. The results of this method's test indicated that the homogeneity of variability in this study was not intense and, consequently, has no bearing on the dependability of the research's conclusions.

Furthermore, Harman's single factor test (Harman, 1967) was performed to confirm the existence of CMB. A substantial amount of CMB is present for this test if a single factor emerges from the factor analysis or if a single general factor accounts for the majority of the covariance among the variables (Podsakoff et al., 2012). The questionnaire items were subjected to principal component analysis with varimax rotation, which revealed the existence of nine distinct factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0. These factors account for 64.45% of the total variance. Moreover, the first (and most significant) factor accounted for 26.11% of the total variance, which is significantly less than 50% (i.e., the minimum threshold to test for CMB based on Harman's single factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Since more than one factor emerged and no single factor accounted for the majority of the total variance, CMB was less likely to have significantly confounded the interpretations of the results of the present study (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

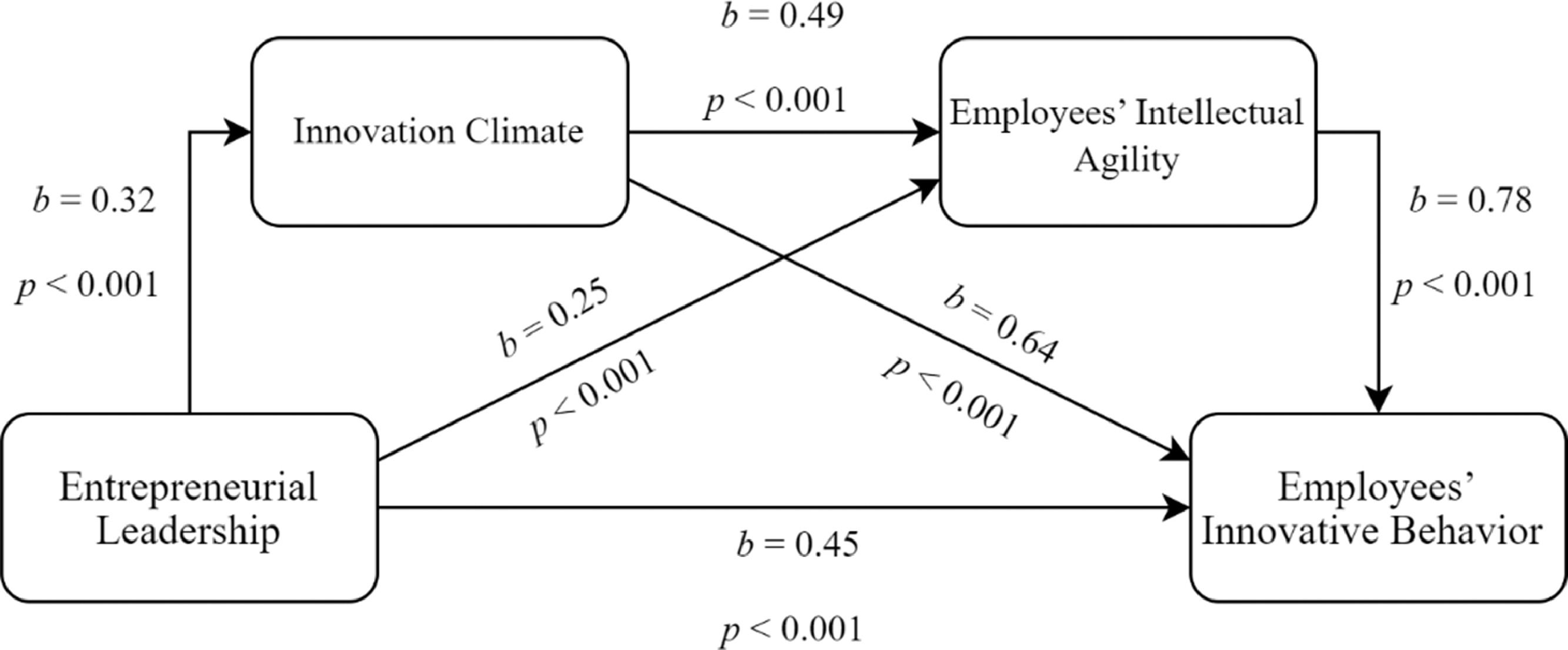

Hypothesis testingTable 3 provides a summary of the regression analysis outputs for hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4. As the models had tolerance values far above 0.2 and Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) far below 5, all models were not susceptible to multicollinearity (Bowerman & O'Connell, 1990). Hypothesis 1 was supported as entrepreneurial leadership positively predicted innovation climate in Model 2 (b = 0.32, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 2 was also supported as innovation climate positively predicted employees’ intellectual agility in Model 5 (b = 0.49, p < 0.01). Next, hypothesis 3 was supported as employees’ intellectual agility positively predicted employees’ innovative behavior in Model 10 (b = 0.78, p < 0.01). Lastly, hypothesis 4 was supported as entrepreneurial leadership positively predicted employees’ innovative behavior in Model 8 (b = 0.45, p < 0.01; See Fig. 2).

Summary of the hierarchical regression results (unstandardized coefficients) (N = 241).

| Innovation Climate | Employees’ Intellectual Agility | Employees’ Innovative Behavior | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 |

| Intercept | 3.47⁎⁎ | 2.33⁎⁎ | 3.85⁎⁎ | 2.97⁎⁎ | 2.16⁎⁎ | 2.07⁎⁎ | 3.49⁎⁎ | 1.91⁎⁎ | 1.28⁎⁎ | .50 | .01 | .025 |

| Gender | -.20 | -.13 | -.11 | -.05 | -.01 | .01 | -.39⁎⁎ | -.29⁎⁎ | -.26⁎⁎ | -.30⁎⁎ | -.25 | -.24 |

| Age | -.09 | -.02 | -.01 | .04 | .03 | .05 | -.19⁎⁎ | -.10 | -.13⁎⁎ | -.18⁎⁎ | -.15⁎⁎ | -.11 |

| Education | .16 | .07 | .09 | .01 | .01 | -.01 | .37⁎⁎ | .24⁎⁎ | .28⁎⁎ | .30⁎⁎ | .26⁎⁎ | .22⁎⁎ |

| EL | .32⁎⁎ | .25⁎⁎ | .13⁎⁎ | .45⁎⁎ | .27⁎⁎ | |||||||

| IC | .49⁎⁎ | .39⁎⁎ | .64⁎⁎ | .35⁎⁎ | .18* | |||||||

| EIA | .78⁎⁎ | .59⁎⁎ | .49⁎⁎ | |||||||||

| R2 | .11 | .34 | .03 | .20 | .28 | .31 | .23 | .42 | .38 | .43 | .47 | .52 |

| ∆R2 | - | .24 | - | .17 | .25 | . 11 | - | .19 | .15 | .20 | .09 | .05 |

| F | 9.52⁎⁎ | 30.84⁎⁎ | 2.37 | 14.64⁎⁎ | 23.32⁎⁎ | 21.62⁎⁎ | 21.90⁎⁎ | 42.38⁎⁎ | 35.61⁎⁎ | 44.99⁎⁎ | 41.35⁎⁎ | 42.01⁎⁎ |

| df | 237 | 236 | 237 | 236 | 236 | 235 | 237 | 236 | 236 | 236 | 235 | 234 |

Note. Gender: 0 = Male, 1 = Female; Age: 1= 18 - 24 years, 2= 25 - 34 years, 3= 35 - 44 years, 4= 45 - 54 years, 5= “54+ years; Education: 1= high school, 2= college degree, 3= graduate degree; EL= Entrepreneurial leadership, IC = Innovation climate, EIA = Employees’ intellectual agility, EIB = Employees’ innovative behavior.

To test hypotheses 5, 6, and 7, Hayes's (2013) PROCESS add-on was utilized. Hypothesis 5 assessed the mediating role of innovation climate on the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ intellectual agility. The results revealed a significant indirect effect of impact of entrepreneurial leadership on employee's intellectual agility (b = 0.12, SE = 0.03, 95% BCa CI [0.07, 0.18]), supporting hypothesis 5. Furthermore, the direct effect of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ intellectual agility in the presence of the mediator was also significant (b = 0.13, p < 0.001). Hence, the innovation climate partially mediated the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ intellectual agility. Furthermore, the results show that the indirect effect of innovation climate on employees’ innovative behavior through employees’ intellectual agility was significant statistically (b = 0.29, SE = 0.06, 95% BCa CI [0.20, 0.39]), supporting hypothesis 6. Lastly, the results show that the indirect effect of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ innovative behavior through innovation climate and employees’ intellectual agility was significant statistically (b = 0.18, SE = 0.06, 95% BCa CI [0.04, 0.10]), confirming the serial mediation as claimed in hypothesis 7. The mediation analysis summary is presented in Table 4.

Summary of the mediation analysis results (N = 241).*

| Relationship | Total effect | Direct effect | Indirect effect | Confidence interval | T statistics | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| EL → IC → EIA | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.13⁎⁎ | 0.12⁎⁎ | 0.07 | 0.18 | 7.07 | Partial Mediation |

| IC → EIA → EIB | 0.64⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.20 | 0.39 | 7.77 | Partial Mediation |

| EL → IC → EIA → EIB | 0.45⁎⁎ | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.04 | 0.10 | 9.03 | Partial Mediation |

Note. EL= Entrepreneurial leadership, IC = Innovation climate, EIA = Employees’ intellectual agility, EIB = Employees’ innovative behavior.

The current research explores the effect of entrepreneurial leadership in encouraging employees’ innovative behavior by creating an innovation climate and increasing their intellectual agility. In terms of both direct and indirect effects, all of the proposed relationships were consistent with those described in the literature. In addition, the data revealed relatively large coefficients of determination, indicating that the model is sufficiently robust to explain employees’ innovative behavior in the context of entrepreneurial leadership. These results suggest that the chain of serial mediation adequately explains these causal relationships and indicates that entrepreneurial leadership has a substantial indirect effect on the innovative behavior of employees. This proves that entrepreneurial leadership practices influence not only the innovation climate in the firm but also its employees’ intellectual agility.

The findings suggest that when leaders enact their roles and tasks based on entrepreneurial leadership principles and not only create new ideas to solve problems and deal with difficulties but also value and support new ideas created by employees and develop strategies and approaches to facilitate innovation and opportunity recognition, employees are encouraged and empowered to challenge themselves and explore, generate and implement new ideas (Gupta et al., 2004; Kang et al., 2015; Karol, 2015). In addition, Kang et al. (2013) have also found in their study that the firm's innovative climate mediates the positive relationship between transactional and transformational leadership and followers’ innovative behavior. Furthermore, the findings from Bagheri (2017) and Bagheri & Akbari (2018) claimed that EL is a critical factor that enables, encourages, and promotes the employees’ innovative behavior. This study added value to these findings by examining the mediation role of the firm's innovative climate between EL and employees’ innovative behavior. Finally, the positive impact of intellectual agility of employees on businesses’ innovativeness corresponds with previous studies which show that human capital impacts innovativeness (Santos-Rodrigues et al., 2010).

Theoretical and practical implicationsThis study has multiple theoretical contributions based on the findings presented in the present study. First, this research adds to the literature on entrepreneurial leadership by developing and testing a new model through which entrepreneurial leadership promotes employees’ innovation behavior. More specifically, we uncover the black box between entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ innovative behavior where the climate for innovation and employees’ intellectual agility play critical roles. We strengthen prior research by demonstrating that the innovation climate and intellectual agility of employees are effective mechanisms that influence the entrepreneurial leadership innovation process. Second, to our knowledge, the innovation literature lacks studies assessing the influence of entrepreneurial leadership on the innovative behavior of employees. Further, we provide unique insight demonstrating that entrepreneurial leaders empower employees to establish a sense of intellectual agility, acknowledge business challenges, seek solutions, generate novel and valuable insights, and recommend innovative solutions by fostering an innovative climate. Leaders also constantly influence the work environment and set the vibe in the organization they work in, including the climate for innovation (Chen & Hou, 2016). As a result, this research extended the leadership styles that encourage innovative behavior among employees to include entrepreneurial leadership (e.g., Karol, 2015; De Jong & Den Hartog, 2010).

Moreover, the findings of this research have wide-ranging implications for business leaders and entrepreneurs, both existing and emerging, who ought to encourage innovation among their employees in order to maximize the growth and competitiveness of their organizations in the long term. First of all, the findings of this study are very helpful in identifying what role business leaders and entrepreneurs play in generating and guiding innovation within their organizations, as well as establishing the ideal environment for innovation within those organizations. In addition, leaders can use the findings of this study as a basis for encouraging entrepreneurial leadership to be used in creating innovative settings that encourage employees to feel confident about exchanging new ideas and concepts in a comfortable and safe environment. Furthermore, entrepreneurship academics can use the research's findings to help both present, and future business leaders understand their new responsibilities and assignments, as well as develop their entrepreneurial leadership skills and abilities to lead innovation in their businesses (Karol, 2015). Last but not least, employees should be aware that intellectual agility can have a significant impact on how innovative they are in their work, which is why they need to develop their abilities to recognize and analyze multiple perspectives and analyze the factors that are changing over time, and devise new solutions on a continuous basis.

Limitations and future researchThere are, however, certain limitations to the study that should be addressed. These are both limitations and opportunities for valuable future research. First, entrepreneurial leadership is the only antecedent that is considered in the framework. Future research may compare entrepreneurial leadership and other styles of leadership to determine whether they have distinct outcomes or mediation mechanisms. The sample is another potential drawback of the current study. The research sample was limited to the United States; therefore, this study should be reproduced in various cultural contexts to validate or refute its conclusions. Despite the fact that controlling for individual variations had no significant influence on the model based on the current data, future studies could examine the model for individuals of different ethnicities and those with less education to confirm its generalizability further. In addition, future research could expand our knowledge of the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and innovative behavior by exploring vital personal attributes and team-level mechanisms. For instance, DeRue et al. (2011) found that employees who are more open to experience and have a greater cognitive entrepreneurial intention engage in innovative initiatives more actively while also demonstrating more significant levels of creative performance (e.g., Siyal et al., 2021). Finally, although we investigated emergent states such as innovation climate support, we also strongly encourage researchers to explore the moderating impact of team effectiveness (Chen et al., 2013) as well as team potency (Avolio et al., 1996), which may assist translate the positive impact of entrepreneurial leadership on employees’ innovative behavior.

ConclusionIn this study, we utilized social cognitive theory to gain a deeper understanding of how entrepreneurial leadership can foster and reinforce innovative behavior. Our study explores how entrepreneurial leadership influences employees’ innovative behavior, and we find that intellectual agility and innovation climate play essential roles. Study findings revealed that both innovative climate and employees’ intellectual agility mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and innovative behavior.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approvalAll procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with 1964 the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data availabilityThe datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.