This study examined the influence of the Western Australian and Iranian startup ecosystem contexts, including the powers and liabilities that determine startups’ commercialisation outcomes. By utilising a theoretical framework based on programme evaluation, explanatory theory building, and critical realism, a cross-contextual comparison study was conducted. The study showed that the context of startup accelerator programmes and the startup ecosystem is an important determinant of commercialisation outcomes. The study revealed factors that impede startup accelerator programme success, including low follow-on investment, ecosystem immaturity, the ineffective agency of the Western Australian and Iranian governments, low levels of talent among startup agents, and the shortcomings of the startup accelerator programmes. The research confirmed that programme evaluation is a suitable theoretical base for the evaluation of startup accelerator programmes by determining what works, for whom, in what context, and why. It extended the existing body of knowledge by developing the change models of the startup accelerator programmes studied in the context of Western Australia and Iran, which can be applied in research on other startup accelerator programmes in different contexts.

In recent years, many governments have come to understand the increasing significance of startups and innovative businesses and their ability to compete and survive economically in changing work environments (M'Chirgui, 2012; Ojaghi et al., 2019). Recent years have seen an increase in the use of startup accelerators (SAs), an innovation-focused programme that seeks to help startups to develop innovations and accelerate the process of commercialising their products (Pauwels et al., 2016). SAs design startups’ plans within a wider context in which they work to facilitate the conversion of innovative startup ideas into commercially viable products (Mansoori et al., 2019; Mian et al., 2016; Pauwels et al., 2016; Wise & Valliere, 2014). The accelerators provide a set of support services to selected startup teams within time-bound programmes of acceleration. Services include physical space, education, funding, training, mentoring, and networking (Cohen et al., 2019; Cohen & Hochberg, 2014). Qualified startups that engage with accelerators prepare an initial version of their products with the support they receive (Mansoori et al., 2019; Ries, 2011), setting in motion opportunities to connect with venture capitalists willing to invest in their startup ideas (Cohen et al., 2019; Cohen & Hochberg, 2014).

Startup accelerators address different startup needs that range from innovation and scaling to the creation of long-term partnerships and value in terms of better brand positioning. The objectives of each accelerator may affect how best performance should be measured (Moroz et al., 2024). Malek et al. (2014) found that accelerator performance could be greatly affected by local-level resource conditions, along with stakeholder involvement and market dynamics. This nuanced view of accelerator capability and their contextual relevance creates a sound basis for optimising support strategies to achieve improved commercialisation outcomes across diverse ecosystems.

Although SA programmes are supported by many economies to promote a positive startup innovation and commercialisation environment, there is a substantial gap in scholarly work studying the impact of SA programmes on the commercialisation success of startups, especially relating to implementation across different ecosystems. Although several studies have considered the general benefits of SA involvement, few have explored variations in the contextual factors in geographical and economic landscapes that may influence effectiveness. This current research seeks to fill the critical gap by exploring two distinct startup ecosystems from Western Australia (WA) and Iran. The former represents a semi-mature ecosystem with robust governmental support for innovation, whereas the latter is an emerging ecosystem operating under immense economic challenges, including international sanctions. This comparison seeks to clarify how SA programmes can enable or impede commercialisation opportunities for startups in the different startup ecosystems of WA and Iran.

These two ecosystems were selected for two reasons. First, two ecosystems can be compared: in one, the government promotes the strategic development of the startup ecosystem and in the other the government has begun some preliminary startup development measures but suffers from international sanctions and other economic issues. The second reason was the convenience of data access and an understanding of the contexts; Iran is the home country of one of the authors, and WA is where all authors now live.

In general, the study seeks to answer: How do the SA programmes in diverse ecosystems differ with regard to commercialisation outcomes, and what contextual factors explain these differences?

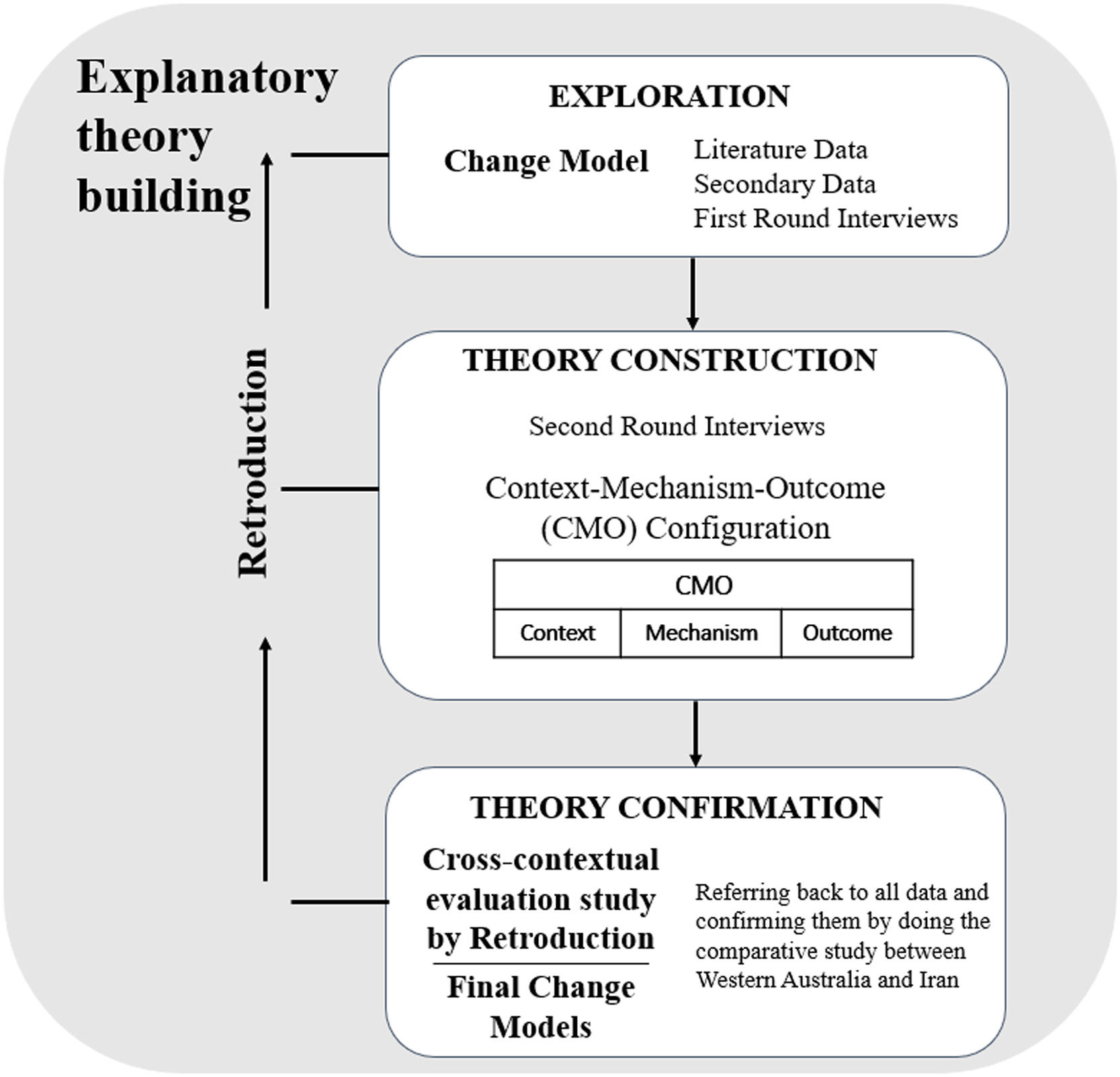

To explore and construct the theory of SA programmes in the contexts of WA and Iran, the research used a theoretical framework based on Chen's (2014) change model of programme evaluation. This model was combined with a modified version of Eastwood et al.’s (2014) three phases of explanatory theory building (emergent, construction and confirmatory phases), and Danermark et al.’s (2002) six-step methodology of explanatory research (description, analytical resolution, abduction, retroduction, comparison, concretisation and contextualisation), all under the philosophical paradigm of critical realism (CR).

The examination of the specific SA contexts of WA and Iran (structures, agents, and mechanisms) and the ecosystems in which they operated helped identify the factors that determine commercialisation success and strategies for improving the outcomes. A multilayered theoretical framework allows exploration of the causal links or mechanisms between ecosystem factors and the performance of startups. We use CR to uncover deep structures and generative mechanisms that may not be observable immediately, but which nonetheless have a powerful influence on the outcomes of startup commercialisation.

This study aims to identify, through retroductive reasoning, the necessary contextual conditions for effective startup acceleration, thereby contributing to both theory building and practical applications in entrepreneurship and innovation management. Its primary objective is to provide in-depth and diverse narratives about SAs and their ecosystems to address what works for whom, under what circumstances and why, to enable startup commercialisation. This understanding is intended to support strategies for enhancing commercialisation efforts, providing actionable knowledge for both academic and industry stakeholders engaged in building and supporting high-performing startups. Our rigorous investigation of the interplay between SA programmes and their contextual environments fills a substantial literature gap and contributes a nuanced and effective approach towards fostering innovation and entrepreneurship across diverse economic landscapes.

Theoretical backgroundSA programmesSAs programmes provide time-limited support of three to six months to cohorts of innovation-focused teams that aspire to develop the team's startups (Cohen, 2013; Cohen et al., 2019; Cohen & Hochberg, 2014). Miller and Bound's (2011) definition of SAs has been widely adopted for SA research:

An application process that is open to all, yet highly competitive. Provision of pre-seed investment, usually in exchange for equity. A focus on small teams not individual founders. Time-limited support comprising programmed events and intensive mentoring. Cohorts or “classes” of startups rather than individual companies (p. 3).

Jackson et al. (2015) criticised Miller and Bound's (2011) definition for emphasising several non-essential features of SAs, such as equity participation and small teams, while overlooking essential ones requiring further research. Jackson et al. (2015) distinguished essential and non-essential features as being 1) (essential features) open application process, highly competitive, provision of pre-seed investment, time-limited support, programmed events, mentoring of participants, mandatory networking, and 2) (non-essential features) team focus, shared workplace, run as cohorts, equity participation, periodical meetings, demo-day for graduation, contribution to the strategic objectives of the accelerator, seed and growth funding phase, supervision by a professional organisation.

A consensus among researchers and practitioners is that the key features of SA programmes differentiate them from other startup-focused organisations (Cohen & Hochberg, 2014; Dempwolf et al., 2014; Isabelle, 2013; Mian et al., 2016; Radojevich-Kelley & Hoffman, 2012). Miller and Bound's (2011) definition of SA programmes was extended by Walters et al. (2014) and Heinemann (2015), with a focus on five interdependent business features: (a) seed funding, (b) cohort-based entry and exit, (c) co-location, (d) a structured programme, and (e) mentoring (Bliemel et al., 2016). Cohen et al. (2019, p. 1782) stated that SA programmes provide “networking, educational and mentorship opportunities by drawing in peers and mentors from the wider regional community: for example, successful entrepreneurs, accelerator programme alumni, venture capitalists, angel investors, attorneys, accountants, or corporate executives”. A systematic literature review on accelerators conducted by Crisan et al. (2021) highlighted the top five supports that SAs provide at the startup level: funding, validation (product or idea), product development, network, and knowledge. The review introduced mechanisms of learning, validation, access and growth, and innovation as key explanatory characteristics of SAs that represented specific functions performed by them.

In general, qualified startups enter SA programmes and work on their business ideas while receiving educational and mentorship opportunities on their entrepreneurial processes and aspirations (Cohen et al., 2019). During this time, the startup prepares an initial version of the business venture, known as the Minimum Viable Product (MVP), with minimal time and resources allocated (Mansoori et al., 2019; Ries, 2011) that can be presented to investors and venture capitalists on the demonstration day (Cohen et al., 2019; Cohen & Hochberg, 2014). Considering the significant role of SA programmes for a startups’ commercialisation opportunity, this research evaluates the SA programmes of WA and Iran, as well as powers and liabilities in those ecosystems that promote or obstruct commercialisation outcomes.

Startup ecosystem and supporting startups in the ecosystemInvestigating the working ecosystem of startups is an important consideration in the study of SA programmes. In general, the term ecosystem refers to a community of living beings as agencies interacting with each other and the environment (Cohen, 2006; Tripathi et al., 2019). The concept of a startup ecosystem has grown extensively since 2010, transforming traditional businesses to be innovative and technology-centred by using internet and communicational technologies (Cukier et al., 2016).

Cukier et al. (2016) defined a startup ecosystem as “a limited region within 30 miles (or one hour travel) formed by people, their startups, and various types of supporting organisations, interacting as a complex system to create new startup companies and evolve the existing ones”. Dedehayir et al. (2018) defined startup ecosystems as “the collaborative effort of a diverse set of actors towards innovation, as suppliers deliver key components and technologies, various organisations provide complementary products and services, and customers build demand and capabilities”. Mazzucato and Robinson (2018) observed that a startup ecosystem refers to a dynamic environment that relies on the nature of relationships and partnerships between various innovation actors (including startups, research and educational centres, institutions, organisations, and public sectors) to institutionalise innovation perspectives and create socio-economic value.

The proliferation of startups in recent years has seen a corresponding growth in the number of innovation ecosystems and types of agents and actors working in them. A two-way relationship exists between innovative startups and their operational ecosystem: startups bring recognition to the ecosystem through their participation in the startup ecosystem, and they rely on the ecosystem for their growth. Also, environmental factors such as the diversity of knowledge, local and public research, university proximity, availability of startup-focused organisations, and access to banking resources influence the emergence of startups (Ojaghi et al., 2019). The present research focuses on the importance of the startup ecosystem as a contextual aspect (in WA and Iran) and determines the effect of this context on how SAs are required to work and plan their activities.

Startups are enabled to find support opportunities by the existence of ecosystem enablers such as universities, incubators, accelerators, investors, mentors, research institutions, and government (Thomas & Georgee, 2020) as well as being enabled to develop their ecosystem networks (Haines, 2016; Mason & Brown, 2014). The reality of innovative startups is that they experience many challenges, because numerous weaknesses influence the performance of newborn innovative ventures. They require the support of external parties as well as environmental conditions conducive to sustainable survival and growth (Littunen & Niittykangas, 2010; Ojaghi et al., 2019).

Early-stage startups are mainly isolated from existing networks because first, at this early stage, the market cannot accurately recognise their value and, second, they lack sufficient professional market knowledge, causing problems in commercialising their ideas. To cope with the difficulties and weaknesses faced, startups require appropriate supervision and support (Ojaghi et al., 2019). Accelerators are a type of enabler, characterised by a highly systematic approach that develop entrepreneurial competency to successfully pitch a business idea to an investor (Thomas & Georgee, 2020). Accelerators make it feasible for startups to connect to the community of actors or agents in the startup ecosystem, such as mentors, investors, and successful entrepreneurs, and benefit from applied knowledge and support services (Walters et al., 2014).

Although accelerator programmes are recognised as one of the principal driving forces in the development of startup networks (Walters et al., 2014), their role in the achievement rate of startup businesses and accelerator programmes is significantly differentiated by the features of different startup ecosystems (Frimodig & Torkkeli, 2017). Effective SAs in the US startup ecosystem with experience in supervising successful startups include Y Combinator, Techstars, 500 Startups, and AngelPad (Mansoori et al., 2019). The establishment process for startups differs greatly between highly mature startup ecosystems like Silicon Valley, semi-mature contexts (e.g. WA), and immature ones (e.g. Iran). The context and characteristics of different startup ecosystems must be carefully considered as each one may be required to work differently to facilitate the commercialisation of successful startups. There is a need to investigate what structures, mechanisms, and agencies working in immature and semi-mature ecosystems of SA centres can lead to successful commercialisation outcomes.

The next section outlines programme evaluation as a theoretical background to explain the powers and liabilities at work in both SA programmes and startup ecosystems that influence commercialisation outcomes of startups.

Programme evaluation as a theoretical background to support accelerator programmesProgramme evaluation is a theoretical framework that examines the extent to which a programme is focused on achieving its intended results (Argyrous, 2009; Brousselle & Champagne, 2011; Chen, 2006; Chen & Chen, 2005; Hall, 2008). Programme evaluation, as defined by Chen and Chen (2005), involves the systematic use of evaluation approaches, techniques, and knowledge to evaluate and enhance the planning, execution, and success of programmes. Several researchers (for example: Argyrous, 2009; Bickman, 1987; Chen, 1990, 2006, 2014; Chen & Chen, 2005; Weiss, 1995) have introduced programme evaluation as a tool to illustrate how different programmes work or do not work to achieve their intended outcomes, and to explain the reasons for such performance. Programme evaluation is more than a practical instrument; it is also a method of looking at the full spectrum of how SAs behave in their own environments.

Chen (2014) introduced the change model as an evaluation component to understand the roles of stakeholders in facilitating the process. The change model identifies three components of cause-and-effect relationships within a programme: 1) intervention, the combination of programme activities that affect the relationship between the determinants and the outcomes; 2) determinants, the mechanisms that play a mediatory role in the relationship between the intervention; and 3) outcomes, the anticipated effects of the programme (Chen, 2006, 2014; Chen & Chen, 2005).

The present study used Chen's (2014) change model to establish the conceptual framework for SA programmes (see Fig. 1). The research focused on the role of the SA programmes by looking at the influence of the startup ecosystems of WA and Iran to identify the key structures, mechanisms, and agents that facilitate startups for successful commercialisation in those SA contexts.

The change model of SA programmes (Adapted from Chen, 2014).

In comparing the WA and Iranian contexts, this study discusses the three phases of explanatory theory building (Eastwood et al., 2014), combined with six steps of Danermark et al.’s (2002) methodology of explanatory research for SA programmes, dealing with the evaluation of how the startup ecosystem contexts matter in WA and Iran, including the role of government; that is, their influence on how different CR elements work together to determine what works for whom, and in what context. In addition, the change models will be examined for SA programmes to provide explanations about how powers and liabilities in the WA and Iranian ecosystems influence the commercialisation efforts of successful startups. The resulting change models, which include the influence of the ecosystem context and the role of the government, will be presented at the end of the paper.

The next section outlines CR as a relevant research paradigm for the present study of SA programmes.

Research questions addressedTo construct an explanatory theory of SA programmes the present paper uses Danermark et al.’s (2002) methodology of CR and the modified explanatory theory building method of Eastwood et al. (2014). It addresses four research questions:

- a)

How do the SA programmes work in different startup ecosystems, that is, WA and Iran, to support commercialisation outcomes?

- b)

What ecosystem features including the role of the government, affect the commercialisation success or failure of startups in the different startup ecosystems of WA and Iran?

- c)

What features of agents or agencies play a role in the WA and Iranian startup ecosystems to promote or hinder successful commercialisation outcomes?

- d)

What contextual mechanisms (powers and liabilities) play a role in achieving or obstructing commercialisation outcomes in the startup ecosystems of WA and Iran?

CR is the philosophy of reality (Bygstad, 2010; Dobson, 2001; Dobson et al., 2007; Frauley & Pearce, 2007; Sayer, 1999; Yeung, 1997), applying ontology and epistemology to investigate natural and social realities (Bergin et al., 2008; Yeung, 1997). CR starts with ontology, the theory of being that tries to identify what exists in reality then shifts the focus to epistemology. Epistemology, the theory of knowledge, looks to answer questions relating to the creation of knowledge about what exists in the real world (Bergin et al., 2008, 2010).

CR uses a stratified ontology that contends that what happens in the actual world is not indicative of the powers operating in the real domain, whether they are activated or dormant. In contrast, unstratified ontologies assume that all existence is what is observed, either in the actual or empirical domain or in both (Sayer, 1999). As Blundel (2007) has stated, “the social world consists of real objects that exist independently of our knowledge and concepts, and whose structures, mechanisms, and powers are often far from transparent”. A CR perspective views the world as distinct from our understanding of what we experience in the world. To form a comprehensive understanding of CR, it is important to define and distinguish between key concepts that play a role in the context of any situation.

Structure refers to “internally related physical and material objects and/or human practices” (De Souza, 2014, p. 142). Internally means that the relations shaped between objects are essential.

Agents are groups or collectives sharing particular properties and the privileges (or lack of them) that come with those properties (Archer, 1995). For example, one could be an infant agent (Poulin-Dubois & Shultz, 1990) or a leader agent or an operator agent within operations (Eriksson & Engström, 2021).

Agency is social action that is enacted by agents, bringing change to their own lives or to society. It is important to acknowledge that the structural contexts surrounding an action are temporal and relational in nature. Furthermore, individuals or social actors can exhibit multiple agency orientations simultaneously (Emirbayer & Mische, 1998).

Culture can be defined as “propositions which reflexive agents consider in their decision making” (Jackson & Richter, 2017, p. 7). Culture encompasses values, empirical and existential knowledge, and symbolic expressions. Different individuals understand their surroundings through these cultural aspects, and as a result, their comprehension may vary. This understanding may relate to ethics, norms, rituals, art, language, and any meaningful object that people experience in their lives (Godwyn & Gittell, 2011).

Mechanisms are “the ways that the causal powers of an object are exercised” (Blundel, 2007, p. 3). A mechanism is “basically a way of acting or working of a structured thing” (Lawson, 1997). They are defined as “inherent to physical and social structures, enabling or limiting what can happen within a given context” (Wynn Jr & Williams, 2012, p. 791).

Causal powers are “potentials, capacities or abilities to act in certain ways and/or to facilitate various activities and developments” (Lawson, 1997). Causation is the process that identifies “causal mechanisms and how they work, and discovering if they have been activated and under what conditions” (Sayer, 1999, p. 14).

The realist evaluation uses context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) models in order to evaluate programmes (Dobson et al., 2013; Jagosh et al., 2015; Pawson & Tilley, 1997, 2004). The process of CMO configuration involves interpretation (abduction) by analysing the context, identifying causal mechanisms, and establishing crucial connections between them, which are important for developing a genuine inference about the causal outcome that occurred between two events (DeBono et al., 2012). De Souza (2016) referenced Archer's work and proposed that the context in the CMO model should be viewed as consisting of structure, agency and culture, and included those elements in a modified CMO model (Table 1) which was used to guide the analysis of the SA and ecosystem contexts of WA and Iran. In the modified CMO model the term culture was replaced with ecosystem to explore the impact of the latter as a significant contextual factor on the efficacy of startup accelerator programmes, and to enable an evaluation of how they perform in the different ecosystems of WA and Iran.

CMO formula for a SA programme.

| C (context) | + | M (mechanisms) | = | O (outcomes) | |

| SA context (contextual features in place) | Structures (SA programmes and regulations) | SA Mechanisms (operating mechanisms in place) | SA Outcomes (commercialisation success) | ||

| Agency (including startups, co-founders, managers, mentors, investors, angel investors, programme coordinators) | |||||

| Ecosystem (Iran, WA) | |||||

For this research, CR methodology was selected to provide accurate insights into the structures, mechanisms, agents/agencies, and causal relationships of the startup ecosystems and SA programmes in WA and Iran that positively impact commercialisation outcomes. CR helps us to understand causal relationships that exist beyond observable phenomena and enriches analysis of inherent mechanisms and structures guiding the commercialisation outcomes of startups. The aim of problematising is to extend conventional inquiry methods by uncovering underlying issues and analysing the order of SA programmes in WA and Iran. As this research has aimed to investigate a largely unexplored phenomenon, it modified three phases of Eastwood et al.’s (2014) CR explanatory theory-building method.

- 1)

Emergent: Through investigation, the properties of SA programmes and the startup ecosystem were revealed, along with the underlying structures that form the programme's features and intended mechanisms to achieve commercialisation outcomes. In this phase, the researchers collected data from research (peer-reviewed academic data) and grey (other data) literature, as well as first-round interviews with ecosystem experts in WA and Iran.

- 2)

Construction: During the construction phase of theory building, the researchers gathered second-round interview data to redefine the CR elements of SA programmes and elucidate the causal effects of programme features.

- 3)

Confirmatory: All previous data were revisited in this phase to confirm whether underlying mechanisms or CMO processes hypothesised in the research were powerful enough to lead to the desired commercialisation outcomes. We also sought confirmation regarding the mechanisms' actions, including their powers and liabilities, in either facilitating or impeding commercialisation outcomes. Additionally, we looked into the impact of contextual factors within the ecosystems of WA and Iran.

Given that this research is exploratory, the modified emergent, construction, and confirmatory phases of Eastwood et al.’s (2014) explanatory theory-building were integrated with the six steps of explanatory research (Danermark et al., 2002) then applied to qualitative data in order to identify CMO processes as middle-range CMO processes for SA programmes that will contribute towards a wider theory of SA programmes. It is worth reiterating here that although this paper seeks to confirm the theory of SA programmes, it still represents middle-level theory, given that this research is exploratory. Section 6.3 will discuss further limitations of this study. Fig. 2 shows how the explanatory theory-building approach progresses from exploration to confirmation, answering specific research questions at each stage.

The six step data analysis approach (Danermark et al., 2002), overlaid with emergent, construction, and confirmatory phases to conduct explanatory research (Eastwood et al., 2014) was applied as follows:

Description: Existing SA literature and data of 41 interviews with ecosystem experts in WA and Iran were used to describe and interpret how these programmes work to support startups through the process of commercialisation. This step falls under the emergent (or exploration) phase.

Analytical resolution: Analysing the components and aspects of SA programmes as themes helped narrow the study's focus to the impact of the programmes and specific ecosystem contexts on commercialisation outcomes. This step also falls under the emergent (or exploration) phase. The analytical resolution in this research guided the cross-context comparison, particularly in the selection of specific themes to compare (Table 2).

SA programme themes as CR concepts.

| Themes | CR concepts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Startup ecosystem (WA and Iran) | Context | ||||

| The context of SA programmes | Context | ||||

| SA programmes | Structure | ||||

| Startups | Agents | ||||

| Mentors | Agents | ||||

| Mentoring | Structure | ||||

| Education | Structure | ||||

| Learning | Mechanism | ||||

| Investors | Agents | ||||

| Investment readiness (of the developed startup ideas) | Structure | ||||

| Networking | Mechanism | ||||

| Emigration | Mechanism | ||||

| Product–market fit | Mechanism | ||||

| Talent Pool | Structure | ||||

| Sanctions and economic issues | Structure | ||||

| The power of sanctions | Mechanism | ||||

| Commercialisation | Outcome | ||||

| No commercialisation | Outcome | ||||

Abduction and theoretical redescription: Components were interpreted and redescribed with hypothetical conceptual frameworks resulting in theorising structures, mechanisms, and agents/agencies. This step falls under the theory-building phase. In this step, second-round interview data were gathered by returning to ecosystem experts to confirm the performance of different structures, mechanisms, and agents/agencies in the SA programmes that support startups for successful commercialisation outcomes.

Retroduction: All the data (research data, grey literature, first and second-round interviews) and results of analysis in previous phases were reviewed to form comprehensive insights of SA programmes in different national and regional contexts, with the aim of offering explanations for whether, how, and why the proposed structures and causal mechanisms influenced commercialisation. This step related to the theory confirmation phase.

Comparison between different theories and abstractions: The power of the identified explanations was assessed and estimated by abduction and retroduction, which also comes under the theory confirmation phase.

Concretisation and contextualisation: The interactions between the various structures and underlying mechanisms, at different levels and under specific conditions, were examined (Danermark et al., 2002). In this case, the different startup ecosystems of WA and Iran and the role played by government in commercialising startup ideas were central considerations. This step falls under the theory confirmation phase.

CR allows us to study more profound mechanisms within startup ecosystems that drive commercialisation outcomes, by concentrating on the deeper structures rather than the observable events alone. Qualitative interviews with ecosystem experts, such as accelerator managers, are crucial for investigating the depth of experiences that exist within these ecosystems. CR informs thematic analysis based on contextual realities derived from interviews with experts. Thematic analysis is commonly used in qualitative research to identify, analyse, and report patterns of themes in qualitative data. It is a systemic process of six steps: familiarisation with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the final report (Kiger & Varpio, 2020). The technique is flexible enough for researchers to adapt to different epistemological frames and research questions (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Kiger & Varpio, 2020). Thematic analysis can be done inductively or deductively based on whether the researchers approach the data with preconceived ideas or allow themes to self-emerge. Researchers should be aware of potential biases and ensure stringent application of the method to maintain integrity in their findings (Tavares et al., 2021). In the present study, this approach enables patterns to be traced across diverse experiences and yet be sensitive to how such patterns may look different in WA's semi-mature ecosystem as opposed to Iran's emerging landscape. Participants for the expert interviews were selected because of their direct involvement with SA programmes, coupled with the rich insights they could offer into ecosystem dynamics.

The data analysis in this research represents two contextual levels: the context of the SA programmes and the wider ecosystem context in WA and Iran, which allows valid explanations of how the programmes work to achieve satisfying outcomes of commercialisation in those two contexts. The change models depict the causal processes generated by SA programmes in the different ecosystem contexts of WA and Iran, representing the set of programme activities (intervention) that focus on changing the determinants (mechanisms) and outcomes (commercialisation or no commercialisation). The CMO processes, including the cross-contextual analysis, are summarised in the next section. The change models for the WA and Iranian startup ecosystems are presented at the end of this paper.

Discussion: cross-context comparison between WA and IranThe result of the explanatory theory building for SA programmes shows that the different contexts of ecosystem development and regulatory systems in WA and Iran have different effects on the SA. The following themes guided the cross-contextual comparison of ecosystems: the investment opportunity, the level of ecosystem maturity, the role of government, the agency of startups, and the shortcomings of the SA programmes.

Investment opportunityThe probability of successful commercialisation for startups can be impacted by the interplay of factors within the startup ecosystem, with low follow-on funding being a notable contributor.

Follow-on investment opportunities in the WA startup ecosystemWA is considered to have a semi-mature startup ecosystem, unlike those of New South Wales, Victoria, or Queensland. In WA there is less follow-on investment (or follow-on funding), making it more challenging for startups to commercialise because of WA's strong dependence and focus on the resources sector (including mining services) and the construction industry. Retroduction indicated that due to WA's prominent economic activities, investors have a greater inclination to invest in the resources sector and construction industry, as opposed to other areas that may pose unfamiliar risk and uncertainty (such as startups in the general technology sector). This factor hinders the development and maturation of the ecosystem, prompting startups to seek opportunities outside of Perth and WA, as supported by the following comment:

So, I think it's less about the fact that people typically in Perth go into mining or whatever. I think it's more the fact that there's a lack of investor appetite for that kind of investment [in technology] and opportunity in this market, in this town. (WA ecosystem expert 13)

With attention given to other Australian cities contributing to Perth's less developed startup ecosystem, there are fewer startups, SAs, experts, and investors in fast-growing areas such as technology and services. These findings confirm that the current ecosystem structure has weakened ability to influence the investment decisions of investors, particularly in areas unrelated to resources and construction. This lack of agency for triggering necessary networking mechanisms that could potentially provide investment opportunities for startups is explained by the following ecosystem experts:

Very few of the projects that went into the accelerator programme ever came out of the other end. And that's not a comment on an accelerator model. It is a comment on the Perth market … [there] didn't really seem to be much appetite for investors or individuals to invest in any of these projects. (WA ecosystem expert 13)

Getting access to investors is difficult in this town. Most investors in this town have made their money in two ways, mining and property. They do not make their money in tech companies. They know that's the future. They know that's exciting. But they made their money in mining or property or both. (WA ecosystem expert 7)

However, although the focus on WA's resources sector and construction industry might be a limitation, the question arises as to why it cannot be used as an advantage to support a startup ecosystem that caters to solving problems in these sectors. The history of WA's advances in the resources sector and its significant potential to generate investment opportunities, employment, and production of value for the state confirms the proposition that the context of the ecosystem in which the startup is located has an important effect on startup commercialisation success. The evidence from the interviews supports the suggestion that the WA government has an opportunity to leverage the potential of supporting startups in activities associated with its competitive advantage in the mining equipment, technology, and services (METS) sectors.

We actually would be better focusing on how we could actually leverage the mining and energy and agricultural areas. Because we've got the best in the world sitting here in our own backyard. If you look at the capabilities that we've built, in mining and resources and the energy side of things, there are some of those technologies that can actually cross over into space. So, we should be thinking about where there are worlds where our technologies can contribute to. (WA ecosystem expert 8)

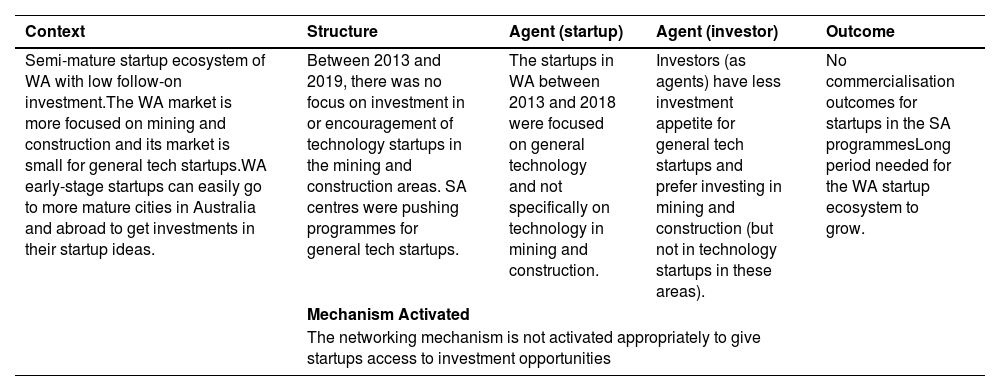

Table 3 presents a summary of how the semi-mature startup ecosystem in WA failed to capitalise on its competitive advantages in resources and construction. There was little or no commercialisation because the networking mechanism did not generate sufficient follow-on investment.

Weak (little or no) commercialisation due to low follow-on investment in the Western Australian Ecosystem: Underlying contextual and mechanism-related causes.

| Context | Structure | Agent (startup) | Agent (investor) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-mature startup ecosystem of WA with low follow-on investment.The WA market is more focused on mining and construction and its market is small for general tech startups.WA early-stage startups can easily go to more mature cities in Australia and abroad to get investments in their startup ideas. | Between 2013 and 2019, there was no focus on investment in or encouragement of technology startups in the mining and construction areas. SA centres were pushing programmes for general tech startups. | The startups in WA between 2013 and 2018 were focused on general technology and not specifically on technology in mining and construction. | Investors (as agents) have less investment appetite for general tech startups and prefer investing in mining and construction (but not in technology startups in these areas). | No commercialisation outcomes for startups in the SA programmesLong period needed for the WA startup ecosystem to grow. |

| Mechanism Activated | ||||

| The networking mechanism is not activated appropriately to give startups access to investment opportunities | ||||

The analyses of the expert interview data from WA (first- and second-round interviews) and secondary data confirm a focus on mining and construction in general, with a low level of follow-on investment in the semi-mature startup ecosystem. Accordingly, it can be inferred that the agency of investors and their weak appetite to interact effectively with startups (as agents) in order to activate the networking mechanism is a liability. The liabilities caused by the WA context, its structure, and lack of potential investors (agents) limits startups’ access to investment opportunities. It explains why there was little or no commercialisation for some startups. For example, in one of the SA centres in WA, only two of the 15 startups are still operational about five years later. Investors (as agents) were reluctant to invest their money in early-stage startups, being more interested in startups already generating revenue, as corroborated by a WA expert:

I think that follow-on funding is really lacking in Perth … it is so hard to have follow-on funding in Perth unless startups have traction early on, So why? If I would be an investor, I am looking for startups that solve problems and find solutions for customer needs and develop that to solve the problem for more and more people … let you know a solution for hopefully millions of people. (WA ecosystem expert 16)

I did some research in 2018 in WA. Over 9 billion dollars was invested in companies, right? Nine billion. That's a lot of money. And guess how much of that 9 billion went to early-stage technology companies? Zero-point-three percent … mining minerals out of the ground, we can't do that forever. (WA ecosystem expert 7)

The study indicates that WA's ecosystem liabilities or weaknesses had a strong effect on the programme outcomes. It highlights the significance of contextual factors at multiple levels in the study of SA programmes and underscores the necessity of considering diverse contextual aspects when designing programmes to ensure realistic outcomes are achieved.

Follow-on investment opportunity in Iran immature startup ecosystemFollow-on investment opportunities in Iran's immature startup ecosystem are hindered by investor resistance and their low appetite to invest in startup activities (weak investor agency). Because the startup ecosystem has emerged in recent years, investors are neither aware of the nature of startup activities nor able to accept that startups’ activities are unlikely to create a return on investment in the short term.

In Iran, a low investment appetite in the ecosystem is exacerbated by the specific structural element of international sanctions that prevent the nation having an open market and international collaboration (Abdoli, 2020). Here, the notion of the adverse impact of the ecosystem context on commercialisation is reinforced by the Iranian startups’ incapacity to surmount their own low internal demand through endeavours to penetrate international markets or facilitate international payment options for foreign users. Findings indicate the networking mechanism is weak. Although there have been some instances of national success stories for Iranian startups, such as DigiKala, Snap, Café Bazaar, and Tap30, the low level of investor interest can be attributed to a lack of understanding and familiarity with the unique nature of startup activities, as distinct from other types of businesses. To pursue long-term prosperity through investment in startups, investors must be willing to confront greater risks and uncertainties. Iranian interview data demonstrated the problematic effect of an immature startup ecosystem context on successful commercialisation.

Accelerator's policy and strategy [in Iran] is one thing but the main point for no commercialisation is the ecosystem issue … We know that startups need to absorb money in time but when there is not enough funding or follow-on investment in the ecosystem it hurts startups … (Iranian ecosystem expert 15)

Analysis revealed that one of the key reasons for the absence of commercialisation outcomes for startups in SA programmes in Iran is the inability of startups (the liability of the agents) to meet investment readiness requirements and activate networking mechanisms correctly, due to the immaturity of the startup ecosystem and its limited talent pool. Thus, the negative impact of low follow-on investment in Iran is compounded by the low investment readiness of the startups. Table 4 shows the effect of the Iranian startup ecosystem context on the outcome of the commercialisation efforts, specifically in relation to the internal issue of low follow-on investment, combined with sanctions and low investment readiness (or adequate talent pool) of Iranian startups.

Theoretical proposal of the effect on commercialisation outcomes in Iran of low follow-on investment, international sanctions, and lack of investment readiness of startups.

| Context and ecosystem | Structure and agent (startup) | Agent (investor) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immature ecosystem of Iran with low follow-on investment.The problem of the sanctions in Iran, refusing to allow its startups to work in international markets. | The weak agency of startups to meet the requirements of investment readiness (as structure), as seen in the majority of startups in the Iranian SA programmes when compared to those in WA. | The liability of the weak investment appetite of investors caused by their low knowledge and awareness of the nature of startup activities; the problem of the sanctions that preclude inward foreign investment. | Problems of achieving commercialisation in Iran are caused more by the liability of the agency of the startups in activating the networking mechanism rather than simply the low follow-on investment as found in the WA ecosystem. |

| Mechanism Activated | |||

| The networking mechanism was not activated properly due to the negative effect of the low degree of investment readiness (as structure) of startups (their weak agency), and low follow-on investment caused by the low investors’ investment appetite and the sanctions. | |||

Low follow-on investment is a feature of the Iranian and WA startup ecosystems. Furthermore, through retroduction, it was discovered that the level of maturity in the startup ecosystems impacts the support provided by accelerator programmes to startups, as well as the quality of the programmes.

In the immature ecosystem of Iran, there is little collective knowledge of startup activities, and low levels of startup talent (as agents), low follow-on funding, and a weak startup community. In these conditions, SA programmes have structural limitations on the quality of support provided to startups, even in best-case scenarios. This research provides an evidence-based explanation of how the maturity of an ecosystem impacts the ability of SA programmes to effectively and efficiently support startups in achieving successful commercialisation. For example, in Iran's emerging and immature startup ecosystem, which is characterised by a lack of startup knowledge, the mentoring structure cannot effectively activate the learning mechanism. The reason for weak mentoring is due to a shortage of professional mentors, resulting in inadequate guidance and support for startups, which ultimately lowers the likelihood of successful commercialisation. It reinforces the point that matching the right mentor to the right startup is a very important consideration in SA programmes. As the startup ecosystem continues to mature with a growing knowledge and understanding of startups, the availability of qualified mentors with valuable expertise and experience in the field will increase. The degree of matching between mentors and startups (as agents) is expected to improve as the ecosystem develops. Experts corroborate this idea:

Connect startups to expert mentors to help them how to do marketing and advertising … mentors think that they know all about strategies of establishing innovative businesses, however, mostly they have some superficial information. (Iranian ecosystem expert 15)

The finding also applies to WA's semi-mature startup ecosystem. However, since it is more developed than Iran's ecosystem, SA programmes in WA produce better results in terms of matching startups with available experts.

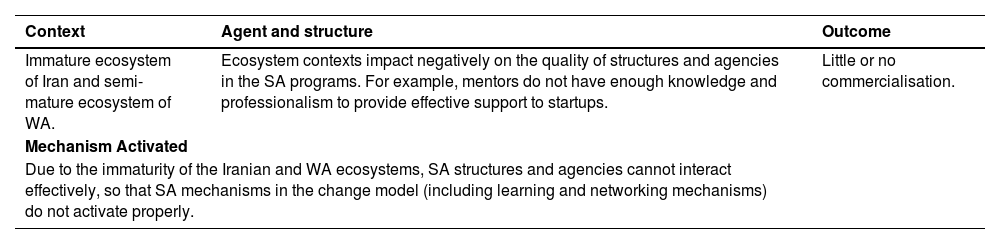

Our research verifies that the effectiveness of SA programmes is somewhat hindered by the underdeveloped startup ecosystem, which has yet to strengthen the functions of the structures, agents, agencies, and mechanisms that play a role in facilitating successful commercialisation. This is why Iran and WA have less success in commercialising startups through SA programmes than mature startup ecosystems (e.g. Silicon Valley with at least 17 years of trial-and-error SA experience).

So, you just got a much bigger ecosystem of people that have had that experience, attract talent … Silicon Valley now has a fast growth, maybe as a result of their experience, culture of sharing experience, mentoring and advice … You don't have that in Perth. (WA ecosystem expert 5)

Retroduction suggests that ecosystem immaturity stems from a lack of qualified agents such as mentors, investors, innovation leaders, and angel investors who possess social awareness and professional startup experience and can interact with each other to support startups in transforming their ideas into commercially viable products on a larger scale. To improve ecosystem maturity, agents must be aware of the context (startup ecosystem) and its effects, be positive and confident in startup activities, and invest in them through the process of commercialisation.

Table 5 shows how commercialisation could fail because of inadequate activation of mechanisms caused by the effects of the broader ecosystem context on structures and agents in the SA programmes themselves.

Theoretical proposal of how the weak power of mechanisms, arising from the effect of ecosystem context on the SA programme context in Iran and WA, leads to the outcome of no commercialisation.

| Context | Agent and structure | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Immature ecosystem of Iran and semi-mature ecosystem of WA. | Ecosystem contexts impact negatively on the quality of structures and agencies in the SA programs. For example, mentors do not have enough knowledge and professionalism to provide effective support to startups. | Little or no commercialisation. |

| Mechanism Activated | ||

| Due to the immaturity of the Iranian and WA ecosystems, SA structures and agencies cannot interact effectively, so that SA mechanisms in the change model (including learning and networking mechanisms) do not activate properly. | ||

The role of government in supporting innovation and startups, and in developing startup ecosystems was examined.

Australian federal government and the WA state governmentIn the WA context, the Australian federal government started the Accelerating Commercialisation Grant programme in 2017 to provide expert advice and funding to small- and medium-sized businesses and startups to help bring their novel products or services to the market. The commercialisation guidance grants were intended to aid startups to develop the commercialisation potential of their businesses, and financial assistance to accelerate commercialisation for trade in Australian or overseas markets (Australian Government, 2021a). The programme provides up to $AUD 500,000 of funding for research commercialisation entities and up to $AUD 1 million of funding for all other eligible businesses.

[The federal government] would probably be the biggest investor in startups in WA. [The federal government] funded 25 companies for 12 million dollars over the last four or five years. [It] funded five companies last year, two and a half million dollars. Right? That would be one of the biggest investors in early-stage in Perth for sure. (WA ecosystem expert 7)

The federal government has also provided support in WA for accelerator programmes and incubators with funding for startups. The programme includes $AUD 13,000 to $250,000 of funding for up to 2 years, covering an eligible project value of up to 65 % in regional areas or up to 50 % in major cities.

WA accelerator programmes and incubators have won this money and can get money to pay for an entrepreneur-in-residence, pay for 50 % of their programme. (WA ecosystem expert 7)

Although this funding was allocated to support the growth of the startup ecosystem in WA, particularly in the technology sector, it appears to have yielded no discernible impact in comparison to the thriving startup scenes in New South Wales and Victoria. As mentioned by WA ecosystem expert 7, funding to early-stage technology startup businesses comprised only 0.3 % in 2018 of the total $9 billion investment overall, an insignificant amount in terms of accelerating positive changes to the WA startup ecosystem. WA experts were of the opinion that the WA ecosystem would perform better and thrive if the funding was increased.

What if we tripled it? That would be game changing. That would give 90 million dollars a year. Now that could make some difference. Ninety million dollars a year, invested in early-stage. (WA ecosystem expert 7)

The Australian federal government has strengthened funding support to startups with research and development tax incentives as part of its regulatory system (Australian Government, 2020). However, the present research found that it is also important to provide education and incentives to motivate investors to invest in startups, given the limited follow-on investment in the WA context because of low investor interest in startups. Additionally, incentivising experienced businesspeople to create or assist startups could be a viable strategy.

They provide funding for accelerators. Okay, great. We don't need another accelerator. I think what we need is to educate investors. We need investor school. (WA ecosystem expert 7)

If we can get lots of experienced people in startups that maybe they need to move on to the accelerators, I think that's where government could really help out. (WA ecosystem expert 16)

This responsibility is not limited to the federal government. The WA state government could add such activities to its small grants programme to better facilitate the commercialisation process for startups and to develop the ecosystem. Small grants to startups are available through the state government's innovation vouchers programme, but these appear to be insignificant alongside the larger funding provided by the federal government.

The state government gives 20-thousand-dollar innovation vouchers [to startups]. That's it, once a year. [The federal government] can give numerous companies hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. (WA ecosystem expert 7)

After investigating the roles of federal and state governments, it was found that they both play a vital role in the commercialisation of startup ideas. Better strategies at both state and federal government levels to educate and motivate investors to support startups’ commercial activities would benefit investors, startups, and the economy. Investments in startups servicing the WA resources sector would be a key target. The study also supported a proposition that some preliminary measures, such as tax incentives for early-stage investors (Australian Government, 2021b), would be a promising starting point in attracting investors’ investment appetite.

Government of IranRecognising that Iran's ecosystem is immature and emerging, the government has tried to promote the ecosystem of innovation and startups with innovation centres, technology accelerators, and knowledge-based and innovative companies. Among the measures adopted by the government are funding and grants for accelerator centres, as well as efforts to motivate Iranian experts and graduates from overseas to use their international knowledge and expertise in knowledge-based companies, or establish innovation and accelerator centres in Iran.

The analysis found that although the government provides support, the ecosystem of Iran continues to lack adequate knowledge and expertise, negatively affecting startup performance and commercialisation opportunities. As discussed in Section 4.1.2 the problematic impact of international sanctions on startups’ commercialisation performance is because investors view investment in the national market of Iran as a risk, whereas they see investment opportunity in targeting and scaling up both national and international markets. It also influences their ability to connect with established ecosystems and international markets, which provide access to information on startup and ecosystem development worldwide. Without such connections and access, Iranian startups and SA programmes have few opportunities to learn from the experiences of prominent international ecosystems and their experts (including mentors, innovation leaders, investors, and successful entrepreneurs), as revealed in the following comments:

Low knowledge is a problem in our ecosystem that the whole ecosystem suffers from. The reason for it? From one point, there is not a flow of knowledge because our doors are closed to other countries that have knowledge … people discuss with each other and ask several questions but [here] there is no one to know the answer for that. (Iranian ecosystem expert 12)

[Our] immature ecosystem [is because of two reasons] first, different elements that form the ecosystem identity are not fully functional; second, risk of investment. (Iranian ecosystem expert 15)

It can be theorised that the outcome of little or no commercialisation is caused by the absence of the international networking mechanism (a lack of opportunity to connect with overseas and international markets), and the inability to access up-to-date knowledge, and seek investment opportunities. It is different in WA, with opportunities for SA programmes to facilitate overseas travel for startups so that they can benefit from professional mentoring and networking with investors and other agents in mature ecosystems (e.g. Silicon Valley). Without that same opportunity, Iranian startups are unable to follow up commercialisation opportunities. With limited knowledge in underdeveloped environments local investors lack interest in investing in startups. Their lack of participation creates a negative causation loop because the context will not mature and become attractive for investment.

In Iran the emigration mechanism is a critical mechanism that impacts few or no-commercialisation outcomes. Specifically, tertiary-qualified Iranian talent is increasingly motivated to emigrate to other countries because of, for example, unemployment, economic stress, with little confidence and hope for their future livelihood because of political and economic issues in the ecosystems’ structure, a further consequence of sanctions and restricted access to international markets. The emigration mechanism has created a human resource crisis (outcome) in the accelerator subsector (therefore a shallow pool of qualified startups) as well as in the startup ecosystem (a lack of knowledge sharing and deficient supervision expertise). The accelerator loses qualified startup members mentored during the acceleration programmes and is unable to find qualified startup teams in the startup ecosystem, as stated by an expert:

The emigration is going to increase, and we usually lose our qualified members, startup members or mentors or staff, as a result. It is a kind of crisis we have regarding human resources. Then, another factor is the internal economics. When money is not substantial, the acceleration programmes could not do as well. Emigration is a result of lack of hope in the current condition. (Iranian ecosystem expert 9)

Table 6 illustrates the proposition that Iran's startup ecosystem is still immature with little or no commercialisation, despite efforts by the Iranian government in recent years to promote it, overcome the effects of sanctions and emigration, and empower knowledge access with support for Iranian experts and graduates from overseas.

Theoretical proposal of how a low speed of knowledge transfer caused by sanctions on Iran leads to the outcome of weak (little or no) commercialisation, despite the agency of government.

| Context | Structure | Agency (government) | Agents (overseas Iranian experts) | Agents (graduate talent in Iran) | Agents (domestic investors) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An ecosystem unable to transfer overseas knowledge and work with international markets, due to sanctions. | SA programmes unable to provide startups with up-to-date knowledge, professional mentors, and foreign investors. | Government, supporting SA programmes and motivating Iranian experts and graduates to collaborate in establishing SA programmes. | To meet challenges of context, Government has started to motivate expatriate Iranian experts to return. | Emigration of graduates because of sanctions and economic issues. | Domestic investors do not invest in startups due to the limitations existing in the ecosystem and high risk. | Despite some promising measures adopted by the government, the low speed of accessing knowledge and transfer to startups is still observable in the ecosystem, impacting the performance of startups in achieving successful commercialisation outcomes. |

| Mechanism Activated | ||||||

| ||||||

In this study, startups are recognised as agents seeking to commercialise their startup ideas with support from SA programmes. The analysis revealed that startups themselves play an important role in commercialisation outcomes. Successful startups show attributes of innovation and entrepreneurship, and the capacity to accept high levels of uncertainty. Such attributes are essential not only for the success of startups (as agents) but also to legitimise their status to encourage investors (as agents who enact their agency by investing) to connect with them (activating the networking mechanism) and invest in their businesses:

But there's a lot of startups I think who are just going through the motions and are not really committed, and they need to commit. And if you're not going to commit, give up your day job, why should anyone else invest and commit? (WA ecosystem expert 7)

Retroduction revealed that in nascent startup ecosystems, such as Iran, there is a limited pool of startups (as agents) possessing the necessary skills and expertise to tackle the challenges of building new businesses. As such, most startups entering accelerator programmes have some preliminary knowledge and expertise, and they understand that their startup activities and efforts are different to establishing a retail shop or a pre-existing type of business. However, during the brief period of acceleration (six to nine months), SA programmes have to provide the learning and education (that is, activate the learning mechanism) to transform novice startup teams into professional startup talent. The short time period limits the depth of advice and feedback that accelerator professionals such as mentors can provide, such as probing the business models of the startups to check the efficiency of their MVP with potential customers and finalising the idea validation process. This is why, despite the importance of key SA structures and mechanisms for structuring mentoring structure and learning, some startups are unable to gain commercialisation opportunities. This proposition was corroborated by the following statement:

[An] immature ecosystem that does not have enough qualified startup … a low talent pool … influences the quality [and then commercialisation]; [a low talent pool refers to] human-related matters and related skills and insight to the startup activities. (Iranian ecosystem expert 3)

By retroduction, the proposition was formulated that it is important for startups (as agents) to already have entrepreneurship knowledge and perspectives, especially at the time of starting their acceleration programmes. A lack of knowledge is a liability for a startups’ agency, a liability that imposes time and cost constraints on SAs and diverts the attention of startups away from crucial tasks, such as validating ideas and scaling up businesses.

The outcome of no commercialisation does not necessarily reflect ineffective structures and mechanisms in the acceleration programmes (see Section 4.5). Here, it can be theorised that the outcome of no commercialisation in the immature ecosystem of Iran results from a deficit of qualified and skilled startups, that is, a weak talent pool. Table 7 sets out the proposition of a small talent pool causing the outcome of no commercialisation.

Theoretical proposal of how the small Iranian talent pool of startups as agents causes an outcome of no commercialisation.

| Context | Agent | Structure and mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immature startup ecosystem of Iran. | The small talent pool of startups. | The SA programmes must associate a significant amount of their time to educating startups about entrepreneurship. Consequently, the mentoring structure and learning mechanisms are not activated appropriately to prepare startups for investment readiness. | Investment readiness is not met by startups because the 6-to-9-month programme is not enough for them to learn entrepreneurial skills and work on their products until the level of investment readiness is achieved.The mentoring structure and learning mechanism cannot work effectively to help startups with idea validation, investment readiness and ultimately commercialisation. |

Based on a comparative analysis of WA and Iran, it can be inferred through retroduction that WA boasts a more talented startup pool, possessing better knowledge and awareness of startup activities, as well as having the requisite skills to navigate the conditions of risk and uncertainty that accompany successful commercialisation. To accurately understand the differences between startups in WA and Iran, it is essential to acknowledge that although WA has a larger talent pool of startups, it would be incorrect to attribute the better commercialisation outcomes solely to the quality of SA programmes and the structures and mechanisms that increase the likelihood of success.

A finding that emerged from the analysis is that Western Australians value a work-life balance and can be “laid-back”, confident about the state of the WA economy and social welfare services, with employment averaging 41.1 working hours per week and a minimum hourly wage of $20. It is an attitude that is not consistent with the nature of startups, which requires hard work under pressure, consuming a considerable amount of time and energy especially in the early stage of business development. Some WA startups underestimate not only the difficulty and time required for commercialisation, but also that, as agents, they need to sacrifice their normal life. The proposition supporting the theory of what works, for whom, and under what circumstance was supported by an expert who said:

There's a pretty drastic problem with commercialising R&D and ideas in Australia. Why? They want to chill out, and they want to have a family life, and they want to have the beach. And I think those sorts of cultural things affect [startup performance]. (WA ecosystem expert 20)

In addition, the analysis found that startups in immature and semi-mature startup ecosystems do not pay enough attention to the importance of the idea validation process which requires an agency to activate the mechanism that fits the product with the market. Failing to do so results in errors in their business model not being corrected and the adequacy of their product not being proven. A change in this mindset is needed to spend more time on validating their business model and proving that their product features can meet customer needs and compete with existing products in the market. The observation of a WA expert confirms this finding:

Go talk to customers … I think that feedback that you get is so important that if you can understand peoples’ problems and you can get to that solution much faster than by kind of guessing what the solution should be, so talk to your customers. (WA ecosystem expert 16)

A surprising finding of the comparative analysis between the WA and Iranian ecosystem context is that, while the WA ecosystem has a stronger pool of startup talent with entrepreneurial knowledge and perspective than Iran, WA startups are more likely to underestimate the amount of effort required for their startup activities because they want to preserve their culture (or perspective) for maintaining work-life balance. Table 8 shows that the no-commercialisation outcome can stem from the failure of startups to undertake idea validation because of work-life balance issues. It can be suggested that the quality of talent entering startup accelerator programmes and their ability to conduct idea validation largely depends on the level of ecosystem maturity, while the work-life balance culture within startups influences the degree of commitment that teams display towards their responsibilities.

Theoretical proposal of how WA startups’ inability to undertake idea validation due to the work-life balance ethos leads to the outcome of no-commercialisation.

| Context | Agent | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-mature startup ecosystem of WA with the talent pool shortage.The WA culture of work–life balance. | Startups lack the knowledge to do idea validation properly (weak agency). The culture of giving importance to work–life balance reinforces the weakness or liability. | Little or no commercialisation. |

| Mechanism Activated | ||

| The idea validation process is not being met, as startups fail to validate their business and fit their products with the market demand. | ||

This section describes shortcomings that influence commercialisation in SA programmes in immature and semi-mature startup ecosystems. In Iran's immature startup ecosystems, SA organisations have recently been established to test what would be the best programme strategy for them to guide startups to achieve commercialisation. Certainly, it is not appropriate for immature ecosystems to apply models from mature startup ecosystems like Silicon Valley. In fact, some preliminary efforts of that nature failed. SA programmes require consideration of contextual features such as government policies, cultural considerations, and perspectives of people who can impact startups’ performance. Further, they need to adopt strategies to develop startup performance gradually and make improvements to the growth of the ecosystem.

Iranian SA centres have experienced a trial-and-error cycle of developing programme structures and mechanisms in the last five years. Although they have been successful to some extent in increasing novice startups’ awareness of entrepreneurship perspectives and the requirements of innovative-focused activities, there have been shortcomings and setbacks in developing structures and mechanisms, which decreases startups’ prospects of properly validating business models and commercialising their products.

We have had failure for 40 % of startups. The accelerator has had [cases of] no commercialisation. In fintech, having correct communications with big companies in the financial area is so important for the success of accelerators and we need to have better performance. (Iranian ecosystem expert 3)

Despite the mature WA ecosystem, some SA programs and their agents, such as managers, programme managers, mentors, and investors, may lack the requisite knowledge and experience to effectively guide startups in searching for disruptive business ideas and creating solutions that address people's current needs. Although they help startups to make their MVP in a short period and generate sales through marketing, they fall short in advising startups to validate ideas and prove their business model, and to have the confidence they can achieve success, before spending scarce resources on production and product development phases.

There are a very small number of excellent accelerators that help potential startups become something real, and a very large number of startups that will never succeed and are a waste of time. The good organisations are founded by genuinely experienced and amazing accelerator people who have designed a genuinely useful organisation. Those accelerators are that good that they attract the best talent far and wide. Advertising is not really a “thing”; they attract people because they make news with their success. (WA ecosystem expert 11)

In addition to the lack of comprehensive knowledge and experience in SAs, some focus on their own profitability by accepting as many startups as possible then evaluating success or performance in a short period of time, instead of allocating sufficient time to each startup to help them validate and pivot their ideas to guarantee commercialisation. SAs should pay close attention to the selection of startup talent, help them progress through the learning and adaptation process, work on their business model and revise it until the financial model enters profitability and generates revenue.

So, accelerators, they make money or make a business by helping startups, but they don't help them find the business. They help them do marketing. They help them do sales, they help them do product development, they help them get PR [public relations]. These service providers aren't aligned to help the company find success. This is why they do this, because they want the greatest number of startups; they want to get as many companies in trying to build their business so they can make money and make a life. (WA ecosystem expert 2)

Accelerators are not that successful. Startups are in the idea stage when they come out of an accelerator … accelerators initially want to help startups scale their business and achieve growth while they are in the idea stage, [they] need to validate their idea and get a new customer; however, accelerators think startups are ready when they come in (WA ecosystem expert 5)

Another shortcoming is that some accelerators have the misconception that a six- to nine-month SA programme is enough for startups to validate their business model and generate revenue. This approach might be true in mature startup ecosystems such as Silicon Valley, where startups have developed their startup models and worked professionally on them before getting extra support from accelerators. However, in the ecosystems of Iran and WA, startups are likely to be in the idea stage when entering the programme and, in some cases, it takes a few years for their business model to become viable, which requires the SA programmes to be patient with startups and offer regular monitoring and guidance during the post-acceleration programme phase to increase the chances of business survival and viability.

Be careful and not try to impose a Silicon Valley on Perth. Silicon Valley developed in the 60 s, south of San Francisco because of the universities and research and new technology and computers, technology … Perth should develop its own specific system, not just try to impose a Silicon Valley model on the location … Perth is still very young, running eight years old. We are developing quite fast. (WA ecosystem expert 7)

Startup culture in Australia is very different to Silicon Valley although the culture in Australia is very similar to America and Silicon Valley. Much more money, probably more risk-taking in Silicon Valley compared to Australia, particularly Perth, where people are very conservative in terms of their money. They invest in resources sector or invest in property, but they don't invest in startups. Probably because they haven't got as much money as the people in America. (WA ecosystem expert 2)

The situation is better to some extent in WA's more mature ecosystem than in Iran, and some SA organisations accept startups with initial versions of a product (or MVP) as part of their selection process, allowing more time for idea validation.

Discussion, practical implications, and theoretical implicationsTheory confirmation and the WA and Iranian change modelsThis paper used the phases of emergent, theory building and theory confirmation in explanatory theory building to apply a comparative analysis of the WA and Iranian startup contexts to an adaptation of Chen's (2014) change models of SA programmes. The data was reviewed and analysed to determine the influence of different ecosystems and regulatory systems on the performance of the SA programmes and on startups’ commercialisation opportunities.

Figs. 3 and 4 show the change models of the SA programmes studied in the WA and Iranian startup ecosystem contexts respectively.

The change model for the semi-mature WA ecosystem.

Note. (a) The white boxes in the WA change model represent the set of structures, mechanisms, and agents working together to support the commercialisation of successful startups. (b) Green and blue boxes indicate respectively powers and liabilities of elements in the WA ecosystem, strengthening and weakening the activation of those mechanisms that affect commercialisation opportunities.

The change model for the immature Iranian ecosystem.

Note. (a) The white boxes in the Iran change model represent the set of structures, mechanisms, and agents working together in the programmes to support the commercialisation of successful startups. (b) The blue boxes are liabilities in the Iran ecosystem that weaken the activation or power of mechanisms, impacting commercialisation opportunities.

The solid arrows between components (from an intervention to a determinant to an outcome) represent causal relationships, showing how change in one element causes change in another element. The top components in the change models indicate an element's mediating role, positioned between two other components, with the ability to either strengthen or weaken the relationship between them. In this study the interventions are the SA programmes, and the determinants are mechanisms and causal elements with powers and liabilities that can affect each other and the commercialisation outcome. For example, in Fig. 3 the power of the learning mechanism activated by the accelerators’ skill development plan for startups (to activate the learning mechanism and promote their commercialisation opportunities) has a positive influence in reinforcing the relationship between the mechanisms of the SA programmes’ selection process to select startups, and the startups’ relationships to validate their business.

The change models for the SA programmes studied in the WA and Iranian ecosystems were conceptualised with a focus on programmes evaluation; that is, trying to answer what works for whom and under what circumstances. The models demonstrate the sequence of activities and mechanisms required to enable successful commercialisation outcomes in both WA and Iranian contexts. Each mechanism must operate effectively to activate others, ultimately leading to success. Figs. 3 and 4 depict the theoretical change models for WA and Iran, demonstrating the effective and efficient interaction of SA structures, mechanisms, and agencies. These models factor in the powers and liabilities inherent in each ecosystem and their impact on the successful commercialisation of startups.