Science and technology-based entrepreneurship education (SBEE) is crucial for the valorisation of newly developed fundamental knowledge and innovative technology in science faculties. This is an important factor in enabling science to respond to societal challenges related to sustainability. However, its didactics are currently underdeveloped. Experiential learning plays an important role in SBEE. Against this background, the current study addresses the following research question: What are the specifications of experiential learning for further developing the didactics of SBEE, as identified through systematic assessment? The study reveals that significant improvement is possible when systematic attention is paid to the implementation of four core activities of experiential learning: bringing real-worldness into the learning setting, recognising the ill-defined nature of management problems and entrepreneurial challenges, encouraging involvement in the execution of management interventions, and highlighting the importance of reflection. Furthermore, we draw upon the literature stating that for a transformative experiential learning effect, the sole focus on a business logic in current SBEE needs to be transcended to enable such entrepreneurship and sustainability education to contribute to the kind of out-of-the-box technological innovation solutions required for the current, pressing sustainability challenges that society faces. This study provides the first evidence that dedicated attention to critical reflection is a crucial component in the design of the experiential learning process for science- and technology-based entrepreneurship and sustainability education.

Science- and technology-based entrepreneurship education (SBEE) at the bachelor's and master's levels is crucial for the valorisation of newly developed fundamental knowledge and innovative technology in science faculties. It is an important, if not essential, element in university policy strategies and governance to empower science to respond to societal challenges related to sustainability. SBEE is also a relatively new phenomenon compared to classic management and entrepreneurship education. While traditional management and entrepreneurship education is often provided by business schools and, to a lesser extent, via engineering education at polytechnical universities, SBEE is offered by faculties of science (Blankesteijn et al., 2021).

As an academic endeavour, SBEE is closer to the ambitions of technology transfer offices, science hubs, and start-up accelerators than to the aims of business schools. Business schools have increasingly adopted a purely academic identity with limited connections to the ‘outside’ professional world, thus inducing - according to critics such as Gosling and Mintzberg (2006) and Bennis and O'Toole (2005) - an ‘institutionalized irrelevance’ of their work in society: ‘It [their sole focus on scientific reputation because of, what the same paper dubs provocatively as “physics envy”] gives scientific respectability to the research they enjoy doing [..]. In short, the model advances the careers and satisfies the egos of the professoriate’ (Bennis & O'Toole, 2005, p. 4).

SBEE seeks to escape this logic and the ‘institutionalized irrelevance’ that follows from it, and aims to contribute to the valorisation and sustainability agenda that nowadays, in addition to education and research as two primary missions, often defines the ‘third primary mission’ of many universities (Blankesteijn et al., 2019). These co-existing and interrelated three missions in today's universities have been the subject of considerable debate, as noted by Heller (2022, chapter 1).

While many universities currently shape the three missions simultaneously, the development of universities towards this multi-mission approach over time can also be interpreted as a development of generations of universities. The first generation of universities focuses mainly on education; the second generation builds on this by adding and integrating research; and the third generation adds and incorporates a broader soci(et)al function (Heller, 2022, chapter 1). This evolution arguably calls for the development of a 'fourth-generation university' that addresses the tensions arising from the current emphasis on further developing multiple-mission universities; this is particularly relevant with regard to the third mission, which entails, for example, the involvement of entrepreneurial thinking in and around universities, opinions about the university's role in serving society, and the associated value in addressing societal issues stemming from a request for increased environmental and social sustainability (Heller, 2022, chapter 1).

Not only are the locus and long-term academic ambitions of science-based entrepreneurship education different, so are its practical goals. Science-based entrepreneurship serves, amongst other objectives, to develop and transfer technological innovation from a science/R&D context to one of practical application (Boh et al., 2016). SBEE is built upon the notion that there is a gap between fundamental science and application, and that university-industry technology transfer needs to be facilitated via entrepreneurship education (Lackeus & Williams-Middleton, 2015). Students in SBEE are taught to cross this ‘valley of death’: the gap between research and commercialisation of research, between researchers and entrepreneurs and tech investors. Students need to experience first-hand the drivers and barriers in turning science into commercial application (Barr et al., 2009).

Experiential learning is a central teaching method to cross the valley of death (Van Ewijk et al., 2020). This teaching method has been increasingly employed in management education to essentially bring the real world into the classroom (Yardley et al., 2012). Learning about ‘wicked’ management problems based on experience is an important component of experiential management education. Experiential learning facilitates an in-depth understanding of real-world entrepreneurship and management challenges.

SBEE programmes hence hold the promise of unlocking the huge innovative potential of science and technology for the betterment of society, especially given current societal challenges in the field of sustainability (Klofsten et al., 2019). This raises questions about the teaching methods adopted in these programmes, especially regarding the extent to which they enable experiential learning, which is crucial for management and entrepreneurship education. Some form of experiential learning is required in entrepreneurship education, as research has shown that the creative and innovative abilities needed to develop an entrepreneurial skill set and attitude require experiential educational methods (Van Ewijk et al., 2020).

However, little is known about experiential learning as part of the didactics of science-based entrepreneurship education (Dhliwayo, 2008; Hägg & Kurczewska, 2020; Mujuru et al., 2022; Politis, 2005). Strikingly, the basic principles of experiential learning are often implicitly applied in the design of entrepreneurship educational programmes, which raises the question of how and to what extent experiential learning contributes to the established learning outcomes of SBEE. This has immediate academic and practical relevance since, as Spence (2001, p. 2) puts it, ‘We won't meet the needs for more and better higher education until professors become designers of learning experiences, and not teachers’. The current study aimed to fill the abovementioned gap in the literature. Drawing on the literature on experiential learning, we aimed to analytically determine how this type of learning contributes to SBEE programmes, and what needs to be considered and eventually deserves dedicated attention from teachers and coordinators involved in such programmes.

The following research question guided the study: What are the specifications of experiential learning for further developing the didactics of SBEE, as identified through systematic assessment? The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. First, we present the theoretical background focused on experiential learning. Then, we describe four analytical categories that were developed in the study, rooted in the scientific literature on experiential learning in management and entrepreneurship education. These categories were used to assess, in a conceptual-analytical and exploratory fashion, the contribution of experience-based teaching to developing entrepreneurial intention and action rooted in fundamental, exact science. Next, in the methodology section, we describe the bachelor's and master's programmes in Science, Business, and Innovation (SBI) at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, analysed as a representative case study of SBEE. The design of a set of courses is presented in the results section. In the discussion section, we further explore and interpret the results. By way of conclusion, we discuss the extent to which experiential learning and its didactics contribute to the learning outcomes of SBEE and present lessons and recommendations drawn from this study for other SBEE programmes.

Experiential learning in management and entrepreneurship educationKolb (2003) developed the classic and still dominant approach to experiential learning already in the nineteen eighties, drawing upon the rich and classic learning philosophy tradition, for which John Dewey (amongst others) laid the basis at the beginning of the 20th century (Jarvis, 1987). Kolb's theory is theoretically grounded in educational psychology. Kolb's experiential learning cycle consists of the mental movement of the learner from the translation of concrete experience to reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. He defines learning as follows: ‘the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience’ (Kolb, 2003, p. 45). Thus, learning is enabled, and new knowledge is constructed. This is widely acknowledged as the first comprehensive understanding of experiential learning in developmental psychology. It is comprehensive in the sense that it departs from the assumption that humans have an innate capacity to learn, whereby experience acts as a catalyst for learning (Kayes, 2002, p. 139).

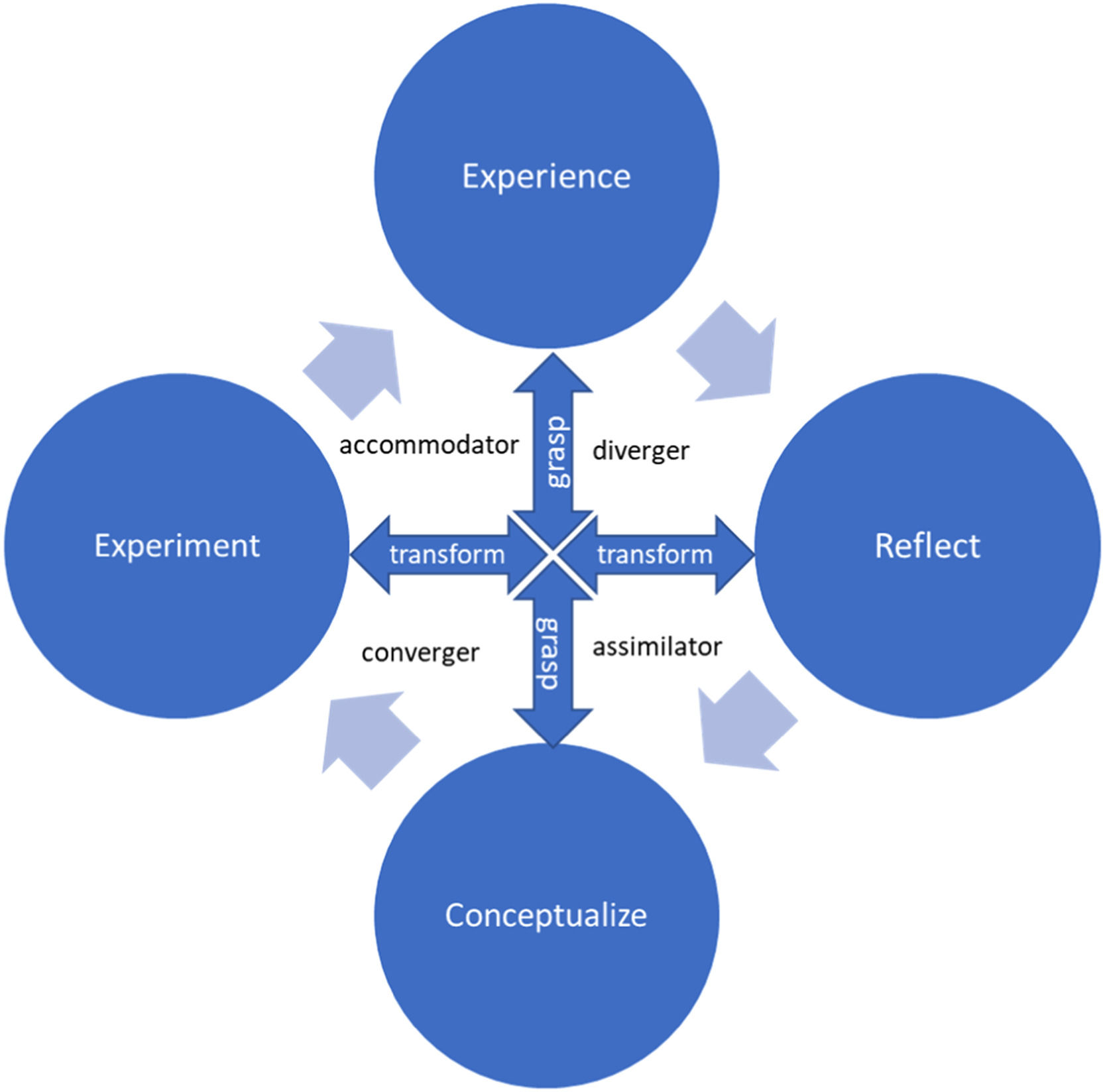

Experiential learning theory defines four phases in the learning process: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation (Fig. 1). In the concrete experience stage, the experiential learning cycle emphasises personal involvement with people in everyday situations. In this stage, the learner tends to rely more on feelings than on a systematic approach to problems and situations. In a learning situation, the learner relies on their ability to be open-minded and adaptable to change. Through reflective observation, people understand ideas and situations from different perspectives. In a learning situation, the learner relies on patience, objectivity, and careful judgement, but would not necessarily take any action. The learner relies on their own thoughts and feelings in forming opinions. In the abstract conceptualisation stage, learning involves the use of theories, logic, and ideas, rather than feelings, to understand problems or situations. Typically, the learner relies on systematic planning and develops theories and ideas to solve problems. In the fourth stage of active experimentation, learning takes an active form, namely, experimenting with changing situations. The learner takes a practical approach and is concerned with what really works, as opposed to simply observing a situation. Learning starts at one of these four stages, not necessarily with the first stage. Per phase, Kolb distinguishes four learning styles that optimise its learning effect, which are related to the different phases of experiential learning: diverging or the diverger (preference for feeling and watching), belonging to the phase between concrete experience and reflective observation; assimilating or the assimilator (preference for thinking and watching), belonging to the phase from reflective observation to abstract conceptualisation; converging or the converger (preference for thinking and doing), belonging to the phase between abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation; and accommodating or the accommodator (preference for feeling and doing), from active experimentation to concrete experience (Mainemelis et al., 2002; McCarthy, 2016). Learners thereby either horizontally iterate on the axis from active experimentation to reflective observation, which, in theory, allows for a transformative experiential learning process, or iterate between concrete experience and abstract conceptualisation, which allows for an experiential learning experience that enhances their grasp of the experience. These learning styles and related processes are arguably relevant in the didactical choices of a teacher, in each phase of the experiential cycle.

Experiential learning: Phases, learning styles, and types of learners (adapted from McCarthy, 2016).

Several authors have further refined Kolb's interpretation of experiential learning. Politis (2005) deduced three main components of entrepreneurial learning based on a comprehensive review of experiential learning: entrepreneurs’ career experience, the transformation process, and entrepreneurial knowledge in terms of effectiveness in recognising and acting on entrepreneurial opportunities and coping with the liabilities of newness. Healey and Jenkins (2000) emphasise the learning styles of students and the importance of matching these styles with teachers’ teaching styles. Further, as Tomkins and Ulus (2016) emphasise, experiential learning can be considered to mark a shift from student-centred learning to relationship-centred learning. Understood as such, it can be seen as a form of sensemaking. Lisko and O'dell (2010) emphasise its constructionist perspective, focusing on social interaction, which makes it especially valuable in medical and nursing education. Specific types of action learning, such as problem-based learning and case-based teaching, have been developed and tested against the background of experiential learning (Perusso & Baaken, 2020; Perusso et al., 2021). Kayes (2002) considers the development of the theory in the context of the linguistic turn in the social sciences and humanities and the role of language in constructing experience. Kayes (2002) refines the experiential learning theory by connecting personal learning to social learning. Tan and Vicente (2019) combine student-centric learning with experiential learning and define experiential learning as constituting work with real-life clients. McClellan and Hyle (2012) emphasise the importance of an unfamiliar context in sensitising students to the experiences in a research context in an anthropological sense.

Meanwhile, the experiential learning theory has also been criticised. Kolb arguably does not pay enough attention to reflection, especially to cognition and emotion as mediating factors in this process (Boud et al., 2013). Kolb also pays relatively little attention to the importance of including a diverse team of teachers in the experiential learning process to do justice, especially with regard to reflecting-on-action, to the diverse perspectives and backgrounds of teachers and learners (Anderson, 2019). Garner (2000) criticised the theoretical underpinnings of learner types and questioned whether learning is confined solely to these learning types (De Ciantis & Kirton, 1996). An important question raised by Smith et al. (2004) is whether learning can indeed be typified in stages. Fenwick (2001) criticises the constructivist outlook of the theory and its lack of attention to context and the role of the teacher. Ord and Leather (2011) doubt the absence of other proven learning styles such as abstract experience, passive learning, and secondary learning. Other criticisms are of a psychodynamic, social, and institutional nature, raising the following questions and concerns: How does his theory reflect psychodynamic processes? What role does the social context and background play (Reynolds, 1998)? How can experiential learning be institutionally facilitated in the educational system (Vince, 1998)?

Despite these refinements and criticisms, Kolb's theory on experiential learning remains immensely influential in research on management education (Fielding, 1994; Robotham, 1995), and has, because of its impact, even been denoted at a certain point in time as ‘taken for granted’ due to its common and widespread acceptance (Beard & Wilson, 2006). It is generally perceived as one of the most influential theories in management learning (Vince, 1998). Blaylock et al. (2009) analyse experiential learning as part of the ‘relevance turn’ in management education: away from the ‘scientification’ of management practice (cf. Bennis & O'Toole, 2005) towards ‘business skills laboratories’. In management education, experiential learning relies on the idea that managers learn, by 1. recognising and 2. responding to a diverse set of environmental and personal demands (Kayes, 2002, p. 140). In business schools, experiential learning theory has been gaining solid ground, for approximately ten years, as an explicitly acknowledged teaching method (Berglund & Verduyn, 2018; Kayes, 2002). From the nineteen sixties until nearly ten years ago, management education mainly focused on teaching theoretical approaches to address management problems (Bridgman et al., 2018; Raelin, 2007). This has changed only in the last decade because of a growing recognition of the need for managers who are better equipped to solve problems in professional practice. Experiential teaching methods are increasingly included in management education in order to close the ‘relevance gap’ between education and practice – that is, the extent to which management education prepares students for real professional life as an (R&D) manager; for instance, for solving complex management problems for which a traditional theory-based management education programme does not prepare them sufficiently (Perusso et al., 2020).

SBEE, one of the newest fruits on the tree of management education, emerged due to a shift in the perception of the relevance of academic research and education in society. The main task of academic education has long been understood as preparing students for an academic research career only. However, the position and task perception of universities has shifted to include research and education that makes references to and is conducted in a real-life context of application (Blankesteijn et al., 2019). An important driver of this development is the idea that economic progress can be achieved through scientific innovation. However, despite increasing scientific knowledge, commercialisation based on innovative findings in science generally remains limited, especially in Europe (Anon., Dealroom, 2023).

Entrepreneurship education is widely perceived as the missing link here, which is manifested in a growth of academic programmes focusing on teaching (science-and tech-based) entrepreneurship (Barr et al., 2009) and increasing attention to thematising entrepreneurship at strategic levels (Blankesteijn et al., 2019). Experiential teaching, based on Kolb's understanding, has proven to be a highly effective teaching method in entrepreneurship education (Pryor, 2016). Experiential learning is a requirement in entrepreneurship education (Van Ewijk et al., 2020), as discussed above. Although many task-related skills can be taught through a traditional didactic approach, the creative and innovative abilities needed in entrepreneurship education presuppose and require experiential educational methods (Henry et al., 2005).

Experiential learning in teaching praxisThe following are relevant questions for teaching praxis: What does learning that starts with experience mean, on a fundamental, epistemological level, for our understanding of the development of new knowledge, skills, and attitudes? How is new knowledge developed and constructed by learners in experiential learning, and how does this process differ from a classical, cognition-focused idea of learning? What does this mean for teaching practices? Indeed, the mechanisms underlying learning and knowledge development in the context of experiential learning praxis are fundamentally different from those based on the common-sensical understanding of how learning is achieved. Raelin (2007) argues that teaching methods for experiential learning in management education build upon an epistemology that moves away from the classical, strict division between thinking and acting. Experiential learning assumes that through acting, we enrich our thinking - and vice versa. Reflection is pivotal in this process, to optimise the learning effect of moving along this spectrum (Hägg & Kurczewska, 2020).

Experiential learning thus requires a new epistemological vantage point, different from the common-sensical one based on the assumption of a strict Cartesian distinction (‘cogito ergo sum’) between thinking and acting – and consequently, a rethinking of classic teaching methods such as lecturing and in-classroom assignments focusing on enhancing cognition based on assessment of the teachers only. This type of thinking about praxis and experiential learning has its foundation in the ‘practice turn’ in social theory on knowledge development (Schatzki et al., 2001). This epistemology that experiential learning reflects and builds upon also contrasts with the common-sensical and often implicit theory of learning and knowledge development that many teachers hold. The commonsense way in which we assume we understand the world, based on the Cartesian split between thinking and acting, legitimises the classical higher education teaching methods of unidirectional teacher-to-student knowledge transfer, such as lectures. Teachers thereby convey ‘information to a captive and passive student body’ (Raelin, 2007), focusing on the development of intellect and cognition only.

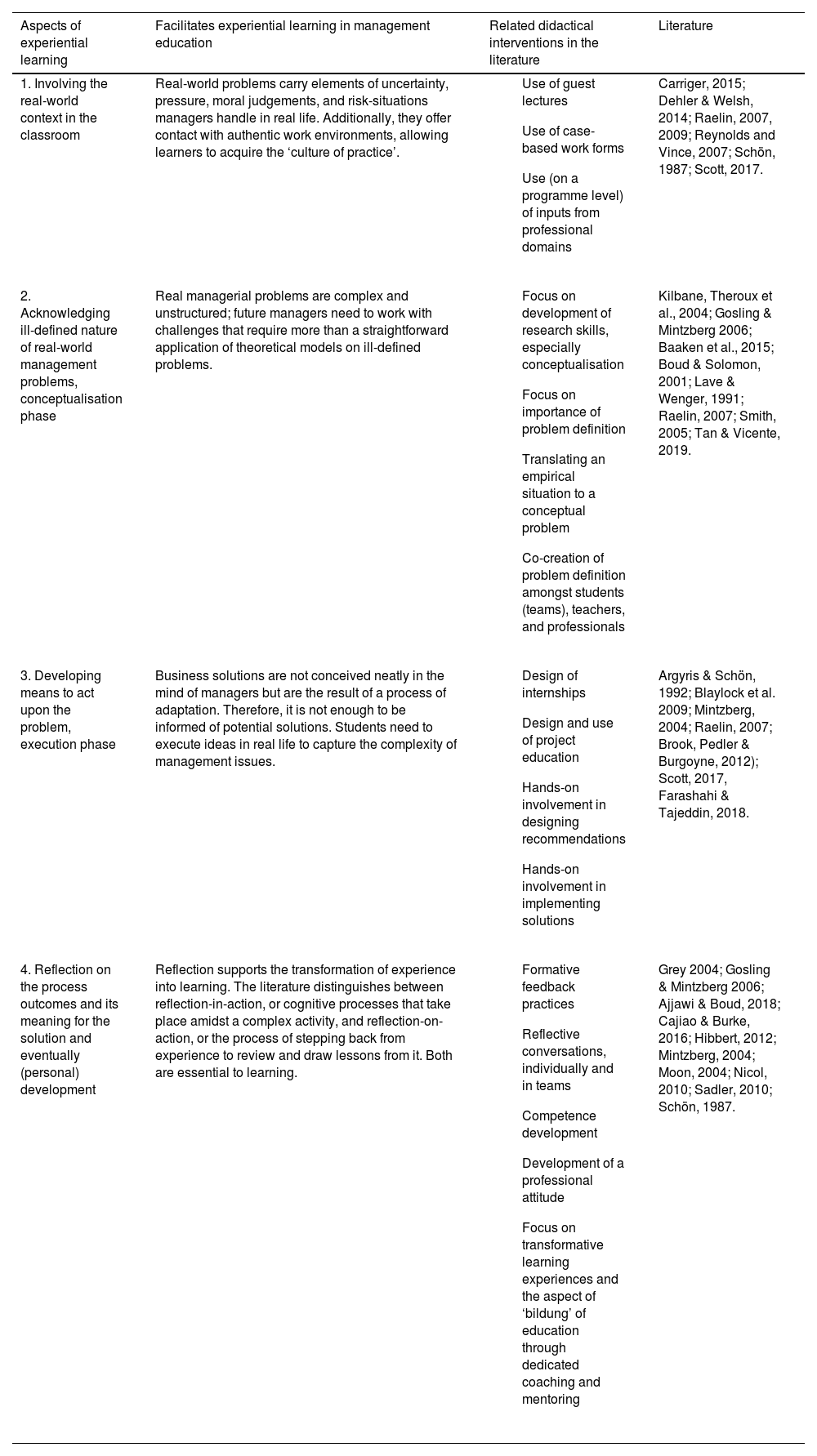

The underlying epistemology of experiential learning, starting from experience instead of cognition, implies that the extent to which the four consecutive aspects manifest in teaching practices needs to be evaluated. These aspects are derived from an extended literature review of research on teaching praxis in experiential learning. The literature, as discussed in the following paragraphs and summarised in Table 2, emphasises the importance of 1. involving an element of real-worldness in education, as referring to the phase of experience; 2. its explicit acknowledgement and understanding of management problems as being in their very essence ill-defined, as referring to the phase of abstract conceptualisation; 3. involvement in the execution of the designed solutions/recommendations, which reflects the phase of active experimentation; and 4. the importance of reflection in the learning process. This study examines educational practices from these four perspectives.

Our research relates to discussions on methods for experiential learning as such, which are indeed currently actively applied in management education practices such as action learning, problem-based learning, and case-based teaching (Bridgman et al., 2018; Perusso & Baaken, 2020; Perusso et al., 2021). However, in the relatively new field of SBEE, considerations regarding tapping into students' learning styles have not yet been explicitly guiding didactical choices in teaching practice.

The literature has often focused on researching learning styles per experiential learning stage and emphasises the need to diversify work forms to optimise alignment with the diverse learning styles of student groups (e.g. Manolis et al., 2013; Kolb & Kolb, 2006). Before making systematic decisions on appealing to learning styles and diversifying work forms, we aim to return to the fundamentals. A thorough understanding of the basic starting point is essential - specifically, it is important to grasp the specifications of experiential learning for further developing the didactics of SBEE in the first place.

We analyse these teaching practices from the aforementioned four perspectives, which are further explored by delving into the bodies of literature that focus on them and are presented in the literature review below. We identified related literature by searching the Web of Science for the most cited papers on the four phases of experiential learning. We then selected papers with a specific focus on their application in the classroom, via concrete interventions. Each body of literature identified in this way circumscribes a phase of experiential learning and proposes and tests certain didactical formats and interventions that operationalise experiential learning. We use these four bodies of literature to construct analytical categories to conceptually analyse the case (Boeije, 2009; Yin, 2009).

Experience: bringing real-worldness into the classroomThe first type of teaching praxis concerns the teacher's recognition of the importance of bringing the real world into the classroom. This is referred to as the teacher attempting to replicate the ‘real-worldness’ of management and entrepreneurship practices (Dollinger, 2008). Students learn to deal with elements of uncertainty, pressure, moral judgement, and risk.

Becoming acquainted with an authentic work environment allows learners to acquire ‘the dynamic and culture of the practice’. Sharing of such insights of the learner with other learners could facilitate discussions of both the broad and specific implications of acquired theoretical knowledge for the practice of university-industry technology transfer.

Carriger (2015) specifically focuses on the role of problem-based learning here, as opposed to lecture-based teaching – whereby the problem is located in the real world. To convey real-worldness, a specific focus on real-world problems that can be encountered in management praxis is needed.

Case-based teaching also uses the real world as a vantage point. Cases can be brought into the classroom via guest lectures, (game-based) simulations, and portfolios of source materials that inform the definition of a real-world case as the basis for case-based teaching (Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018; Sachau & Naas, 2010; Theroux, 2009).

Real-worldness serves to research a case in its full complexity. This serves as a starting point for detangling the case and moving from wicked, ill-defined management issues to a more conceptual delineation. It is about invoking a joint process between students and teachers, whereby they start to consecutively recognise and fully acknowledge the messiness of management problems in the real world. Bringing the real world into the classroom serves as an experiential alternative to the soloistic teacher's act of boiling this complexity down into a neatly ordered theoretical-conceptual problem in classical management education (Druckman & Ebner, 2018; Rosenthal, 2016; Theroux, 2009). It depends on a process of co-creation of the problem definition by both students and teachers.

Abstract conceptualisation: recognition of the ill-defined nature of management problemsThe second body of literature posits that experiential learning occurs when students recognise the inherently ill-defined nature of management problems (Dehler & Welsh, 2014; Gosling & Mintzberg, 2006; Raelin, 2009). Students often struggle to grasp a situation at an abstract conceptual level, as they have traditionally been taught.

Traditionally, management education cases have clear (learning) goals to help students learn, understand, and synthesise theory. The relevant information and answers can be found in the learning materials. This use of cases has been criticised by Raelin (2009, p. 407) as a practice of ‘spoon-feeding’ ‘information to a captive and passive student body’ that ‘tries to make neat an activity that is normally messy’.

However, the nature of management problems in the real world is often complex and unstructured and might disrupt current logic. They are, in their very essence, ill-defined. In experiential learning, this impossibility of defining a problem is perceived as a given. This represents an important starting point for management and entrepreneurship education.

Gosling and Mintzberg (2006) emphasise the importance to teach management education ‘as if both matter’, by which they mean that management education should not aim to overly theorise management to teach students the subject. ‘Education’ is just as crucial as ‘management’ in the learning process. This highlights the importance of making deliberate choices in educational design to acknowledge the inherently ill-defined nature of management problems. Instead of encouraging an immediate reflex to theorise management problems - often a misleading way to make them seem controllable - the focus should be on acknowledging the impossibility of conceptualising the problem, at least without direct involvement in it, that is, the execution phase of experiential learning. Starting with acknowledgement of the ill-defined nature of the problem in the classroom guarantees effective experiential learning (Dehler & Welsh, 2014).

Second, a clear delineation of the problem is required. Socratic methods for questioning, whereby fundamental assumptions are researched via a particular way of posing questions by the teachers, as well as conceptualisation techniques, methods of brain mapping, and structured group discussions serve as means to move from ill-defined problems to abstract conceptualisation. Another technique that Sachau and Naas (2010) discuss are ‘case competitions’, which emphasises the importance of pre-discussing cases in their full complexity before enabling learners to design and execute effective solutions.

Key learning goals that acknowledge the ill-defined nature of management problems include developing research skills and conceptualising these problems as manageable ones. This involves reformulating empirical situations into conceptual frameworks. The process is most effective when exercises in abstract conceptualisation are designed as co-creative efforts to define the problem, with support from students, teachers, and even professionals, in case they are involved.

Involvement in execution as part of management and entrepreneurship educationThe third aspect in experiential teaching praxis researched and discussed in the literature is the execution phase (Blaylock et al., 2009; Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018). In experiential learning, students need to be challenged not only to define problems and design solutions, but also to test these solutions. This phase involves executing the envisioned solution and experimenting with different outcomes. This phase of experiential learning focuses on execution by encouraging students to adopt a learning approach characterised by seeking solutions to problems.

Blaylock et al. (2009, p. 583) discuss the use of ‘business skills laboratories’ in this context, to ‘peel away layers to reveal hidden strategic, economic, competitive, human and political complexities’. Students are immersed in the reality of a business and are mentored by a staff member – differing from simulation as a teaching method, which is often supported by software tools (Hyams-Ssekasi & Taheri, 2022).

Farashahi and Tajeddin (2018) researched how students develop problem-solving skills through experiential learning methods such as case-based teaching, based on a sample of 194 students who participated in simulations of management problems. They confirm the great added value of such methods, as opposed to lecturing alone.

Scott (2017) studied how experiential learning methods contribute to management education, finding a strong positive effect of action learning and problem-based learning on both leadership development and problem-solving skills. Internships and project education provide contexts in which students can experiment with problem definitions and subsequent solutions, enabling experiential learning.

These teaching methods acknowledge the importance of being involved in active experimentation and emphasise the importance of hands-on involvement in the execution of the envisioned solution. Project education is often implemented to provide students with exercises related to developing recommendations and executing proposed solutions.

Reflection as a means to translate experience into new knowledge, skills, and attitudesThe fourth research stream on experiential learning in teaching praxis focuses on the importance of reflection on experience in the classroom (Ajjawi & Boud, 2018; Berglund & Verduyn, 2018; Boud et al., 2013; Cajiao & Burke, 2016; Moon, 2013; Nicol et al., 2014; Sadler, 2014; Schön, 2017). Through reflection, students learn that the process leading to a solution requires stepping back from experience, even while still being immersed in learning at the cognitive level.

Boud et al. (1987) identify reflection as crucial in enabling a process whereby lessons are drawn from experiences, such as through internships. Coaching and providing feedback during experiential learning can serve to stimulate reflection.

Schön (2017) conducted seminal work on reflection, reflective practitioners in particular, highlighting the important role of tacit knowledge in professional practice, developed through experience. Ajjawi and Boud (2018) have also confirmed the importance of reflection. They show that feedback dialogues may be seen as a form of reflection, as they aim to have an effect on learners that extends beyond learners’ immediate tasks. It thus stimulates self-regulatory learning.

Cajiao and Burke (2016) additionally emphasise the importance of psychological safety in social interactions to facilitate learner reflection in management education. Grey (2004) perceives reflection as an antidote to management education as an elitist endeavour and prioritises reflection in what has been dubbed ‘critical management education’ (cf. Berglund & Verduyn, 2018). Nicol et al. (2014) add reflection as a central element in peer feedback processes as a means to optimise the effect of feedback. Sadler (2014) sees a similar role for reflection in feedback, addressing and acknowledging its higher-order effect as compared to feedback only.

Perusso et al. (2020) distinguish three types of reflection that enable such systematic reflection through coaching and feedback: first-order reflection-in-action, second-order reflection-on-action, and third-order critical reflection. First-order reflection-in-action requires students to re-think rules, facts, and theories, and invent and experiment with their new understanding during the experiential learning project. The coaching teacher might point out inconsistencies during the interactions and suggest new directions. Therefore, the teacher creates an active learning environment that stimulates the reflection and development of competencies. As second-order reflection, reflection-on-action considers what happened during the execution but discusses the experiences after the same. The teacher helps students move beyond the intuitive actions that have been taken and develop competencies by understanding their behaviour and considering alternative behaviours that might be more effective. Finally, third-order critical reflection focuses students’ attention on personal and hidden assumptions and aims to stimulate thinking about how personal influences shape their experiences. Feedback and coaching are aspects that a teacher can directly control and consider while designing the educational context.

Hibbert (2013) emphasises the importance of reflexivity in informing thoughtful, responsible, and ethical management practices. He sees reflexive dialogue as valuable to address and make use of diversity in the classroom. It is a means to address power issues, and on a deeper level, spark new perspectives on the ‘sociological imagination’, ideally enabling ‘ideological exploration’ (p. 820).

Further, it assists in, as Bridgman et al. (2018) point out, moving away from the use of cases in experiential learning, as ‘profit maximization toolkits’ only. Hibbert et al. (2010) examined the implications of reflexivity for research practice. They emphasise its importance as part of the research process to rule out bias and develop new principles for understanding.

Reflection can be stimulated through formative feedback practices; reflective conversations with, for example, mentors; and a focus on competence development and professional development. Reflection is crucial as it systematically exercises the skill of critical thinking. Reflection potentially contributes to transformative learning experiences (Frisk Redman & Larson, 2011; Lans et al., 2014; Wals & Jickling, 2002).

MethodThis empirical research involved a case study with embedded units (Baxter & Jack, 2008). The embedded units in the case study were two programmes for SBEE: the bachelor's and master's programmes in SBI at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in the Netherlands. These programmes have been developed over a period of fifteen years.

In our methodology, we combined interviews, observations, and document analysis to gather comprehensive data on experiential learning exercises offered to students in the different programmes. The collected data were meticulously organised in our custom case study databases (Yin, 2009).

The dataset included course guides specifically stating the learning goals of each course, annual reports of both programmes, overviews and discussions of intended learning outcomes, examination files and plans, teachers’ (first-hand) experiences, and digital learning environments and tools (e.g. teaching materials such as lecture slides). The data represent course materials and official documents as well as the first-hand experiences of the authors involved in the programme in crucial management positions.d

These documents represent formal statements on the content and position of the educational programmes at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. They have been used in formal government-ordered accreditations of the educational programmes, events aimed at providing information to prospective students, and yearly management and control cycles of the university. The documents have been written and compiled by key professors, directors, and advisors involved in building, implementing, and managing the programmes.

Data triangulation was performed to validate our findings. The data were triangulated by cross-comparing these documents (Farquhar et al., 2020). We also sought feedback from those involved in the programmes. We conducted fact checking of different versions of this paper by these key actors and/or related academic staff members to ensure the reliability and validity of the outcomes of this study and their corresponding descriptions (Yin, 2009).

Case studyThe case study with its two embedded units focused on the bachelor's and master's programmes in SBI at the Faculty of Science at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in the Netherlands. SBI students study how (natural) science can be developed into economically, socially, and ecologically viable opportunities, in turn contributing to commercially and socially valuable products, services, processes, methods, and approaches. First, students gain natural scientific knowledge in the disciplinary fields of chemistry and physics, related to topics in the sustainable energy sciences and life sciences. Second, they learn about the social and scientific fundamentals of innovation sciences, business processes, and organisational sciences. Entrepreneurship is a central theme in both programmes. The programmes are offered in the Faculty of Science by the Department of Chemistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences and the Department of Physics and Astronomy. Both the programmes have been formally accredited by the Accreditation Organisation of the Netherlands and Flanders (NVAO), a Dutch-Flemish organisation accrediting higher education programs in the Netherlands and Belgium. Additionally, the bachelor's programme holds the Special Feature Entrepreneurship of the NVAO, a national quality mark that highlights dedicated attention in the programme for the development of students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes related to entrepreneurship. These programmes distinguish themselves from similar programmes taught in other regions of the Netherlands by teaching innovation management at the firm level, together with a strong focus on science-based, technological product innovations stemming from knowledge and insights from the fields of physics and chemistry.

The basic concept of the educational programmes is that students can choose their learning modules, by taking elective natural science courses, social science courses, or courses with an interdisciplinary character. The design of the programmes is such that students have a solid to good background in the natural sciences, social sciences, and innovation sciences, as well as experience with settings in practice in which science-based innovation through valorisation takes place. The emphasis is on two domains: ‘life and health’, focusing on valorisation of drug development, medical technology, and medical treatment, and ‘energy and sustainability’, concentrating on valorisation of clean and renewable energy technology and circular products and production processes. Examples of natural science courses are ‘Materials for Energy and Environmental Sustainability’ and ‘Biomedical Modelling and Simulation’. Social sciences are, for example, covered in the course ‘Business, Innovation and Value Creation in the Life Science Industry’ and ‘New Ways of Working’. Innovation sciences are, for example, represented in courses including ‘Management and Organization of Technological Innovation’ and ‘Entrepreneurship and Innovation’.

Students work on projects in and for companies during the programmes. In the bachelor's programme, students engage in innovation projects and the bachelor's project, making up for a total of 48 study credits according to the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) of the 180 ECTS devoted to project-based, case-based education. Half of the SBI master's programme (60 ECTS of the 120 ECTS), that is, the last part of the first, second, and final years, is dedicated to applying natural science and business and innovation science in the empirical field: the science project of 24 ECTS in the first year, and the master's project of 36 ECTS in the second and final years. In the last part of the first year, students apply the appropriated knowledge in the science project. The master's project is dedicated to studying the integration of natural sciences in commercial business trajectories in practice. Students learn about integration in theory and practice. They gain practical experience through the science project and the master's project.

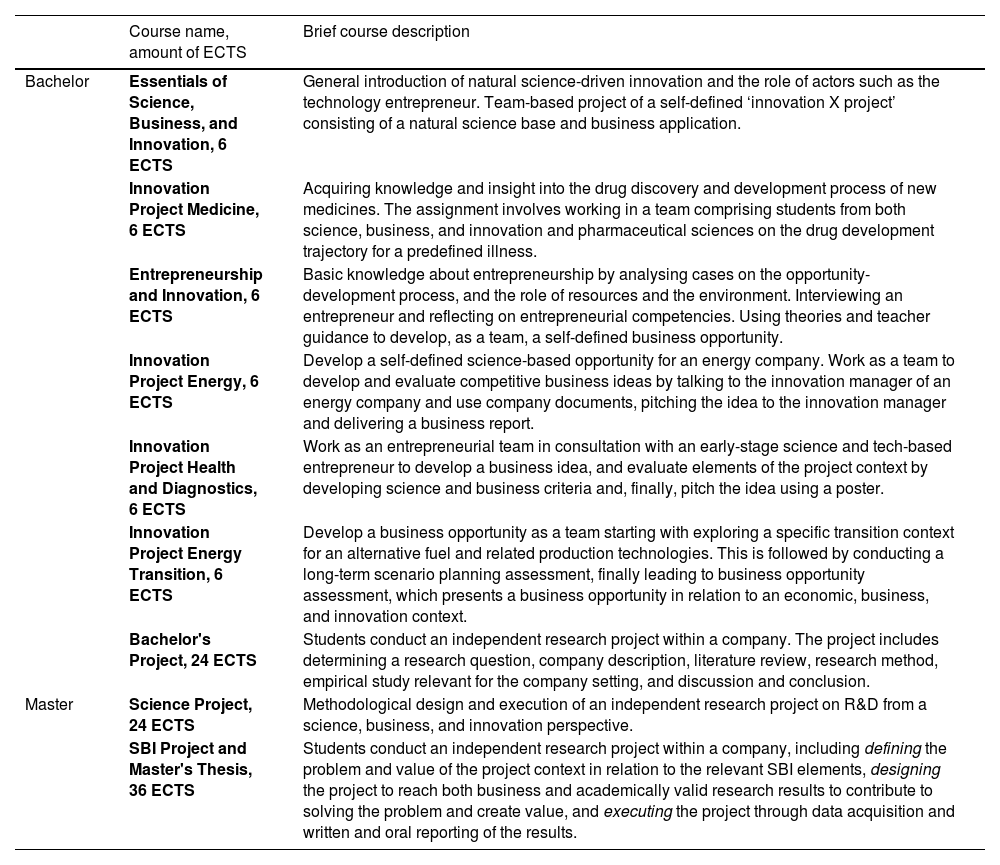

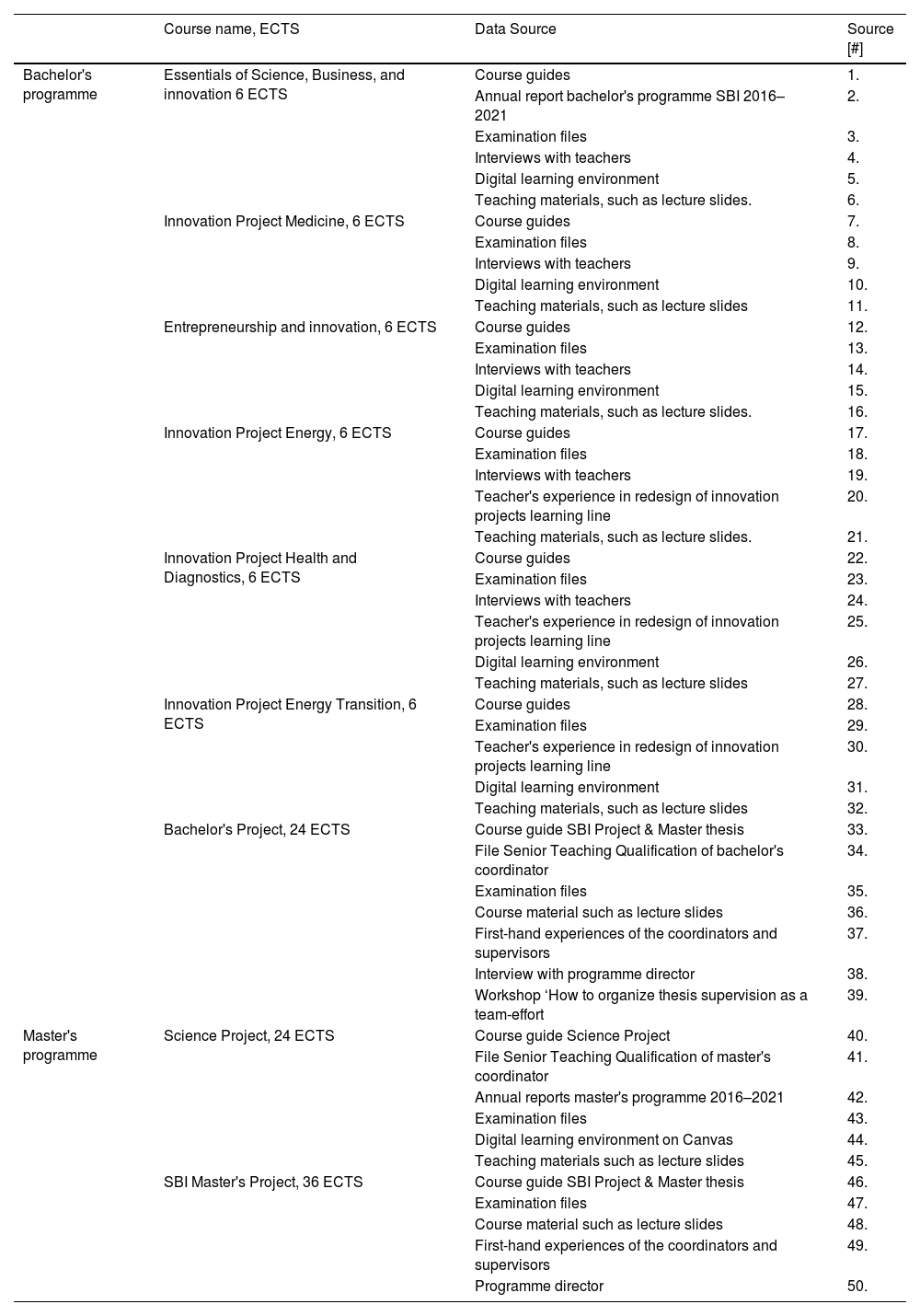

Data collectionTable 1 presents a selection of courses from the SBI bachelor's and master's programmes that generate both theoretical and practical student experiences linked to science- and technology-based entrepreneurship. The courses meet the fundamental basis of elements discussed in Section 2. Experiential learning is especially important in SBEE (Henry et al., 2005; Pryor, 2016; Van Ewijk et al., 2020). As previously discussed, factors supporting experiential learning in the classroom assist in constructing and reconstructing experiential learning processes in teaching praxis in these programmes. As such, lessons drawn from these programmes could be useful for similar academic educational programmes in other settings.

Experiential learning in the bachelor's and master's programmes in SBI at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Abbreviation Meaning: ECTS, European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System; SBI, Science, Business, and Innovation; R&D, Research and Development.

Below, we present a literature-based analytical framework constructed to enable a structured and literature-guided empirical case study. Table 2 presents an overview of the four aspects discussed in the literature review. The analytical framework serves as an instrument for systematically studying, categorising, and discussing findings from the empirical cases (Yin, 2009). By identifying themes in the existing literature and analysing them in the two embedded cases, we were able to recognise the broader meanings and implications of the experiential learning exercises in the case study (Boeije, 2009).

Experiential learning in management education.

| Aspects of experiential learning | Facilitates experiential learning in management education | Related didactical interventions in the literature | Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Involving the real-world context in the classroom | Real-world problems carry elements of uncertainty, pressure, moral judgements, and risk-situations managers handle in real life. Additionally, they offer contact with authentic work environments, allowing learners to acquire the ‘culture of practice’. |

| Carriger, 2015; Dehler & Welsh, 2014; Raelin, 2007, 2009; Reynolds and Vince, 2007; Schön, 1987; Scott, 2017. |

| 2. Acknowledging ill-defined nature of real-world management problems, conceptualisation phase | Real managerial problems are complex and unstructured; future managers need to work with challenges that require more than a straightforward application of theoretical models on ill-defined problems. |

| Kilbane, Theroux et al., 2004; Gosling & Mintzberg 2006; Baaken et al., 2015; Boud & Solomon, 2001; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Raelin, 2007; Smith, 2005; Tan & Vicente, 2019. |

| 3. Developing means to act upon the problem, execution phase | Business solutions are not conceived neatly in the mind of managers but are the result of a process of adaptation. Therefore, it is not enough to be informed of potential solutions. Students need to execute ideas in real life to capture the complexity of management issues. |

| Argyris & Schön, 1992; Blaylock et al. 2009; Mintzberg, 2004; Raelin, 2007; Brook, Pedler & Burgoyne, 2012); Scott, 2017, Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2018. |

| 4. Reflection on the process outcomes and its meaning for the solution and eventually (personal) development | Reflection supports the transformation of experience into learning. The literature distinguishes between reflection-in-action, or cognitive processes that take place amidst a complex activity, and reflection-on-action, or the process of stepping back from experience to review and draw lessons from it. Both are essential to learning. |

| Grey 2004; Gosling & Mintzberg 2006; Ajjawi & Boud, 2018; Cajiao & Burke, 2016; Hibbert, 2012; Mintzberg, 2004; Moon, 2004; Nicol, 2010; Sadler, 2010; Schön, 1987. |

This study was based on an in-depth, single case study design with two embedded units. This case study generates an in-depth, fine-grained understanding of a situation, phenomenon, and/or setting (Baxter & Jack, 2008). The case study is exploratory, as the didactics of SBEE are relatively under-researched. To aim for generalisability of the findings to comparable cases in universities, that is, to realise analytical validity of the findings for comparable cases (Yin, 2009), an educational programme was chosen that fits within a relatively new and growing landscape of similar educational tracks focusing on entrepreneurship education, as shown by Audretsch and Caiazza (2016), Audretsch (2017) and Clarysse et al. (2009) for entrepreneurship education in general, and more specifically for SBEE, by Barr et al. (2009), Lackeus & Williams-Middleton, 2015 and Maresch et al. (2016).

Appendix 1 provides an overview of the data sources. Each source in the appendix is referred to by a number, which is used for referencing in the results section. Data were analysed using qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Accuracy with regard to representation of the data in the results section was verified by key informants involved in the building and management of the bachelor's and master's programmes, thus applying the principle of data triangulation, which enhances the internal reliability of the data and study (Creswell & Miller, 2000).

ResultsThe results are introduced per embedded unit. First, the bachelor's programme in SBI is introduced, followed by the master's programme in SBI. The courses introduced in Table 1 are discussed according to each element of experiential learning.

Bachelor's programme in SBIEssentials of science, business, and innovationEssentials of Science, Business, and Innovation (ESBI) is the first course students take in the bachelor's programme in SBI [1]. It offers an overview of the main theories and proceeds to apply them in the practical domain, thus introducing real-worldness. It focuses on developing an active learning attitude and collaboration competencies through the execution of group assignments [3]. For example, students can choose a case to study - at a rudimentary level - the extent to which a technology is commercially viable. Through a self-defined team-based project, students are stimulated to define a problem and solution for a topic from a predefined list of topics [4]. Here, the element of ill-defined problems comes into play. The teams are mentored during five sessions by academic staff who provide immediate feedback on the intuitively designed business cases by connecting the idea with theories discussed during lectures, stimulating reflection-in-action [2]. Moreover, guest lectures are conducted to bring practice into the class, thereby enhancing real-worldness [5]. Although reflection is part of the course, there is no systematic approach to reflection in the form of a learning activity, and it therefore only takes place in an informal fashion [6].

Innovation project medicineThe context of the course is provided by the development of a medicine for an illness such as COVID-19 or malaria, which is informed by real-world incidents. A unique feature is that the student team consists of both SBI and pharmaceutical science students [7]. Therefore, students have the opportunity to work with people from a different knowledge community [8]. Both types of students have followed similar mono-disciplinary science background courses; however, SBI students also have knowledge of and experience with business and innovation. This allows for a comprehensive process of developing a joint problem definition [12]. Together, they execute a team-based task [7]. During the project, coaching sessions are essential. They are oriented towards the execution of practical tasks, but also encourage reflection in- and on-action. Because of the nature of the case, in some instances, it can be noted to contribute to transformative learning, whereby students become aware of the type of logic at play at a deeper, personal level. In addition, a lecturer-coach facilitates and guides interaction [11]. This coach plays a key role during the meetings by focusing on the task and ensures that all tasks have been completed and feedback has been incorporated [10]. Another example is the final coaching session, in which the coach makes sure that everybody follows a constructive approach to talking about peer feedback and that all individual students formulate experience-grounded learning goals for the next project. After the final session, the students discuss their most important learning moments in a reflection report. Reflection is thus a central element in this course [9].

Entrepreneurship and innovationThe course covers several topics such as the entrepreneurial mindset, the entrepreneur, resources and their development, and the influences of the context in which entrepreneurship takes place [15]. Students are also required to interview an entrepreneur of their choice, whereby the professional network of teachers is activated to guarantee input from the professional domain [12]. Such entrepreneurs serve as important role models for students and, in some cases, act as mentors [16]. When students share their interview experiences, they often remark that they acquired a different understanding of what it means to be an entrepreneur – which sensitises them to the ill-defined nature of the phenomenon ‘entrepreneurship’. A more practical perspective in the course involves students developing a team-based business idea [17]. Starting with problem and solution ideation, followed by analysing the business idea with information and models, such as Business Model Canvas and Value Proposition Canvas, they end by pitching their ideas to a jury [13]. The course deepens their knowledge base by requiring them to read and discuss articles that link the models with theoretical concepts such as ‘dynamic capabilities’, ‘pivoting’, and ‘legitimacy’ [14]. Teachers purposefully design the learning activities to first generate experiences and then guide students’ reflections on theoretical topics through dialogue and assignments. Students reflect on their own practical experiences and compare them with the insights gained from the interview with an entrepreneur [14].

Innovation project energyThe company at the centre of this innovation project specialises in charging electric cars and works on balancing the electric grid. Students are encouraged to think like business-developers [17]. They are provided with insights and data about the products, services, and company and they interview the innovation manager to learn more about business opportunities, thus providing a real-world basis for their course [19]. The interview contributes to the demarcation of criteria, and subsequently, students conduct an analysis and substantiate this analysis with documents and calculations. A unique aspect of the course is the participation of a stock-exchange listed, commercial company that defines the challenge, thus ensuring real-worldness and participation in the execution of the proposed solutions for the given management problem.

The business developer conducts a lecture about the company and explains what they look for in the business case. Based on the knowledge base of the company, students come up with several business ideas and conduct an interview to gain insight into which opportunity fits best [19]. During the remaining time, the teams search for information and make calculations that support business opportunity. In addition, several guest lectures provide information on relevant business and innovation topics. For example, a sustainable energy consultancy firm provides insight into stakeholder management, or a power grid operator shows how changing energy sources could affect load balancing, thus guaranteeing real-worldness and allowing for a problem-searching and problem-defining strategy related to recognising the problem as an ill-defined problem, one requiring better understanding before designing a solution that can be executed [20].

During the project, the coaching provided focuses on guiding the teams over well-known innovation hurdles. Key elements in the course include focusing on developing business ideas, conducting an interview for the early-stage evaluation of the idea, developing and assessing relevant criteria for the business case, and presenting the business case [17]. Each step is coupled with a coaching session during which the students receive feedback or prepare for an interview or presentation. These topics are connected to parts of the team assignment. Complementary to the team assignment, a multiple-choice exam and writing assignment are included to ensure that each student actively participates [18]. This contributes to the acknowledgement of the ill-defined nature of the problem before actual recommendations and solutions can be designed.

It is important to highlight the focus on skill development through coaching, which is an indicator of reflection in this conceptual analysis [21]. The teams are required to autonomously develop initiatives, for example, by reaching out to the coach and planning sessions, but also in their interpretation of the tasks. Thus, although clear tasks are assigned, the teams have considerable freedom when working on the tasks as long as the deadlines are reached. At the end of the innovation project, the team members conduct a presentation for the business developer of the company. Together with academic staff, the business developer awards a prize to the team that came up with the best business idea, thereby loosely referencing the idea of ‘case competitions’ as described by Sachau and Naas (2010) as a means for experiential learning. The final business report is graded by academic staff and sent for notification to the company. The project concludes with a reflection session [18]. This consists of providing feedback, a session to discuss the feedback and define learning points (and if needed, adjusting grades to align with effort), and handing in a reflection report.

Innovation project health and diagnosticsThe Innovation Project Health and Diagnostics module consists of a team-based project concerning the development of a business case in the life sciences [22]. Students develop a project as academic entrepreneurs, meeting two criteria: (1) a natural science-driven knowledge base informs the development of the value proposition, and (2) the value proposition context in the broadest sense appeals to the domain of health and diagnostics [23]. The course progresses over three weeks, with assignments starting from the science base and macro-level trends to the organisation level. The teams are explicitly instructed to iterate in business case development by generating hypotheses, finding information, testing hypotheses, and developing a grounded understanding [24]. Being information grounded is an important assessment criterion for both the presentation and final report [23]. To support progress in learning, each week begins with a lecture that briefly repeats potentially useful models and theories to generate hypotheses. Immediately after the lecture, the teams start with the assignments. The assignments consist of potentially relevant topics and research questions that stimulate the teams to consider business case development in the broadest scope. The assignment is a broad template that needs to be adjusted to the specific project and context, thus helping students to recognise the essentially ill-defined nature of their case and narrow it down to a manageable size [25].

The project begins with the entrepreneur providing documentation (often scientific articles) highlighting the science and technology base [26]. Moreover, the students define the topics that they want to learn more about. The teams start by interviewing the entrepreneur to gain an understanding of the boundaries of the business case, the questions, and the most important topics to take the next step towards commercial viability. The entrepreneur acts as a role model, adding real-worldness and focusing on the importance of execution [24]. At the end of the first week, the teams must present ideas for technological application using information from the interview and provide insights regarding potentially relevant stakeholders [22]. In the following three weeks, each team member conducts an interview with a stakeholder, which might add new insights for developing the value proposition. The stakeholders could be, for example, medical doctors, insurance companies, technicians, investors, and potential clients. At the end of the course, the teams pitch their results through a poster and discuss the business case with an academic staff member (and sometimes an entrepreneur). In addition, the teams reflect on the individual execution of the project by providing feedback, discussing the feedback and defining learning points, and writing a reflection report. Coaching during this last week's session supports the reflection-in-action process [22]. In addition, in the first three weeks, coaching mainly focuses on tracking progress and providing support for networking. The final business report is graded by academic staff and sent for notification to the entrepreneurs involved.

Innovation project energy transitionThe innovation project Energy Transition takes place at the end of the second year. The project context is sustainable energy transition. The first week consists of an individual assignment to study a policy report and apply it to an alternative fuel use context, such as with hydrogen. For the team assignments in weeks two, three, and four, the teachers determine the team composition [30]. The teams start with a macro-level system analysis of the specific energy transition context. This is followed by a long-term scenario planning assessment. The first two assignments allow for an exploratory investigation of the main problems in upscaling innovative energy technology. In the final week, teams develop and assess a business opportunity, which reflects the execution phase [28]. Each assignment requires the application of theoretical literature and builds upon knowledge gained from previous assignments. Academic staff, together with professionals, provide insight into how the alternative fuel of the first week (hydrogen) might be studied using the theory. Three supporting coaching sessions are conducted. These sessions take place after one day and the teams present their initial information and how it might relate to the theoretical model. The sessions require the team members to quickly apply themselves and move from solely gathering information to presenting an overarching picture [30]. Teachers focus their feedback on the conceptualisation and use of information that stimulates adjustments aligned with the theory. The teams improve the conceptualisation and gather additional information to substantiate the claims further. A day later, they hand in their report for student peer feedback, which is based on discussions with student peers under the supervision of an academic staff member [31]. In the final week, the teams present their business opportunity. In addition, they ask student peers for feedback and write a reflection report, thereby concluding the project. This accounts for the element of reflection [29].

Bachelor's project (Thesis)The bachelor's project takes place at the end of the bachelor's programme and consists of an individual research project within a company, business, or governmental or non-governmental organisation [34,39]. Students must find an internship location and are coached throughout the process by the internship coach [37]. During the project, students are mainly guided by an internship coach and by academic staff [37]. The internship context enables contact with the real world, as a primary aspect of experiential learning. Students then start to define their project [36]. Steps include determining a research question; project and company description; science, business, and innovation literature review; research method formulation; empirical study in a relevant company setting; and discussion and conclusion in relation to the research question. Moreover, the steps help to design the project to reach both business-related and academically valid research results that contribute to solving the problem and creating value, thus contributing to the execution of the designed solution for the problem [37,38]. Finally, the steps help to acquire data and present the results of their study, in writing and orally. In earlier assignments, coaching often involves providing creative inspiration or supporting the adaptation to new information by (re)conceptualising the project in different ways. The project is concluded with a reflection report and dialogue with the internship coordinator [35].

Master's programme in SBIScience projectThe science project is full-time and consists of three modules to design and execute a research project that includes science, business, and innovation perspectives and is assessed through an exam and a scientific paper. The first and second modules run parallelly [40]. In these modules, students develop in-depth knowledge on the natural science background and research methodology. Students study the natural physical, chemical, and material science literature. The topics for sustainable energy include (non-)renewable energy sources, energy efficiency, and storage. The topics for health and life include personalised medicine, eHealth, molecular diagnostics, and medical imaging. In addition, students study the methodology and explore how to integrate business and innovation theories into a research project. During the project, students have a high degree of choice in the focus on natural scientific aspects of technological innovation as well as on business and innovation – as long as the focus is on a real-world problem related to science-to-business conversion [41]. This is applicable to, for example, their choice of focus on strategy, structure, culture, or the environment of a laboratory research group. The integration of the natural scientific perspective is achieved through interactive workgroups and an interdisciplinary team of teachers comprising an expert in management, a teacher with a physics background, and a teacher with a chemistry background [40]. Academic staff guide, participate in, and provide immediate formative feedback on the early-stage design ideas. Through discussion and cooperation in both modules one and two, the focus and boundaries of the case become tangible, leading to a research plan. This helps them define the actual problem at hand. The third module involves the execution of the research plan [44]. During this part of the project, the students gather data and employ methods for data analysis. Data are often derived by interviewing experts from the field and collecting documents, which require coding for analysis [43,45]. Through interviews, students often acquire insights into the real-life practice of developing the business case for an innovative technology. Using these insights, students must iterate their project design and create a coherent analysis [42]. One example is a research project on organic photovoltaics and the challenges associated with upscaling this innovative energy technology [45].

SBI project and master's thesisThe SBI master's project thesis is the final research project in the master's programme as part of which students individually design, execute, and report on the research project. The project is also known as an ‘aptitude test’, meaning that the acquired knowledge, skills, and attitudes as learning outcomes of the master's programme in SBI are reflected in the learning goals [46]. The project takes place at and in the context of a science- and/or R&D-driven company, and an internship coach is the main contact person for the student, thus covering the aspect of real-worldness [48]. The project requires that each student carefully manages the research project and deadlines (digital learning environment). At the final stage of the programme, project coaching and support by academic staff are aimed at stimulating autonomy and ownership [41]. The project starts with a project plan. The plan consists of actions and processes related to the preliminary literature review, research questions, research methods and techniques, time schedules, and research goals [47]. Through the choices in the plan, students develop the focus of their project. During the project, three lectures are delivered at the university, together with three question-and-answer sessions about the project. These sessions are essential for providing feedback, so that students can adjust their project accordingly [49]. In addition, students usually consult a wide variety but relevant set of stakeholders to ensure that their answers are valid [50]. At the end of the project, the students write a reflection report consisting of both the business analysis and self-reflection components.

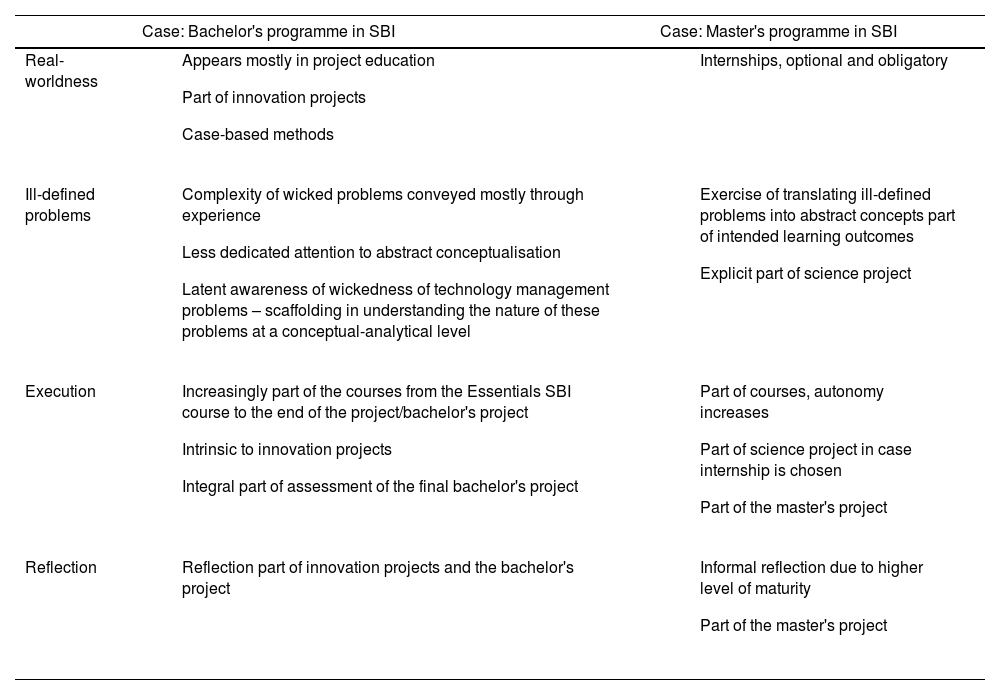

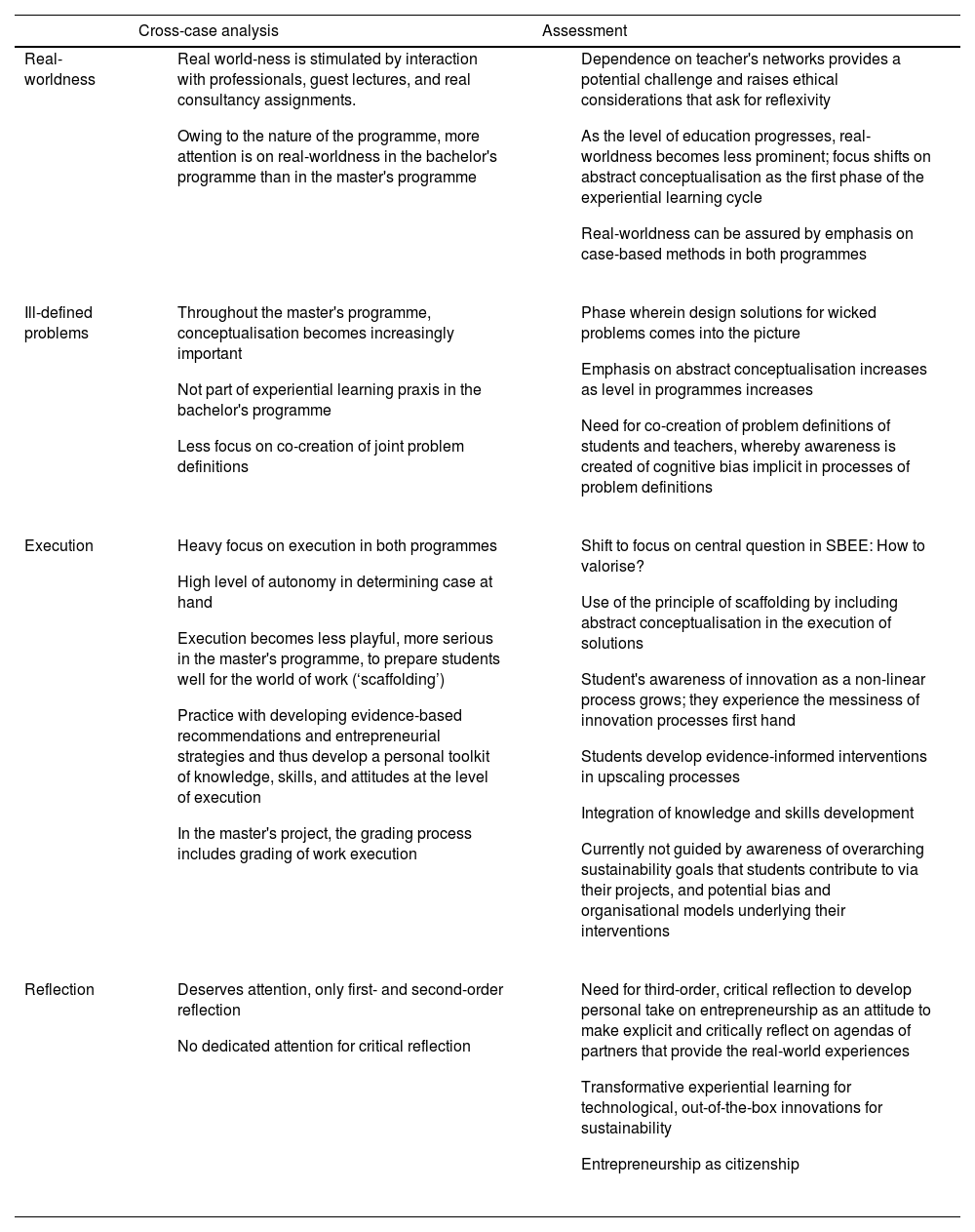

SummaryTable 3 summarises the findings for each embedded unit of the case study.

Summary of findings.

Abbreviation Meaning: SBI, Science, Business, and Innovation.

SBI programmes enable students to learn about and engage with management issues that science and technology entrepreneurs encounter in the real world (e.g. Carriger, 2015; Reynolds & Vince, 2007), define these issues from ill-defined to defined problems (e.g. Boud & Solomon, 2001; Tan & Vicente, 2019), design and execute solutions (e.g. Scott, 2017; Farashahi & Tajeddin, 2008) and reflect on them as an integral part of the learning experience and effect (e.g. Nicol, 2010; Sadler, 2010).

The application of experiential learning principles has evolved in an organic manner in these programmes over the years. It moves from a first encounter with the messiness of innovation processes and science and technology entrepreneurship to making this messiness manageable through the conceptualisation of the problem at hand, and to the design and execution of an intervention in a real-world context. Finally, reflection on the effects of the intervention enables learning from experience.

The following section discusses the conceptual-analytical framework of experiential learning developed following the literature review to structure and discuss the results in a systematic manner.

Experience: bringing real-worldness into the classroomStudents are thoroughly confronted with real-world contexts throughout the programme. Currently, real-worldness is stimulated in classrooms through interactions with professionals, guest lectures, and real-world consultancy assignments. In the bachelor's programme, teachers ensure that the cases are embedded in the real world. Real-worldness is an aspect of entrepreneurship education teaching in the more advanced courses, towards the end of the bachelor's programme. The didactical choice here is that the more students progress through the programme, the more they need to be prepared for the world of work, as Boud and Solomon (2001) discussed in their publication on the importance of real-time involvement in the workplace. In bachelor's programmes, paying constant attention to this has become part of their professional identity (Sachau & Naas, 2010).

At the master's level, SBI students learn that they are able and, in some cases, even responsible, for leveraging the multi-disciplinary backgrounds of all team members to produce effective recommendations for upscaling innovative technology. Theroux (2009) has discussed the importance of leveraging diverse backgrounds in case-based teaching. In the master's programme, both the science project and the master's project and thesis depart from a real-world situation. Students are encouraged to develop an initial understanding of real cases, optionally grounded in management practice in the science project and obligatorily embedded in the master's project and thesis. In the master's programme, the science project and the master's project and thesis, in which internships are optional and obligatory, respectively, a real-world context is crucial for the approval and successful development of the project. The level of these courses is advanced, and the goal is for students to develop a scientific research report that is useful for practice and relevant for academia.

This project-based education involving real-world cases and internships can best be seen as real-time cases, whereby teachers can make use of the real-time case method (Theroux, 2009), which provides students with a more realistic and integrated view of business processes. However, this method creates vulnerabilities in programmes. The dependency on the availability of professional entrepreneurs for experiential learning activities creates potential practical issues when organising education based on real-world cases. Teachers must pay constant attention to their access to suitable professional networks, whereby reflexivity on responsible collaboration is crucial.

Abstract conceptualisation: recognition of the ill-defined nature of management problemsIn the science project, students are actively encouraged to experiment with fitting conceptual-analytical categories to develop an in-depth understanding of the underlying management problem. In the master's project and thesis, they repeat this exercise in a more autonomous fashion to test their skills in autonomous decision-making as researchers and professionals. Gosling and Mintzberg (2007) discuss this as an antidote to the disengagement of management education from practice. The students then choose a theory to further dive into an ill-defined problem and apply it to the case, to get a better sense of the underlying mechanisms at work in the innovation process, either driving or hampering the upscaling of science- and technology-based innovation. The aspect of ill-defined problems and the need for abstract conceptualisation come strikingly to the fore in the master's programme, which is an intended learning outcome in the final term.

Co-creation of a joint problem definition is not part of the chosen teaching methods in either programme. However, it is critically important in this type of education to stimulate eventual reflection on students’ backgrounds and biases. Experiential learning prevents the practice of ‘spoon-feeding’ in entrepreneurship education, which hampers processes of autonomous learning (Raelin, 2009; Dehler & Welsh, 2014). It justifies the focus on (experiential) education in management education, as if ‘both matter’ (Gosling & Mintzberg, 2006).

Through experiential learning and co-creation of problem definitions, students generally become aware that many of their own ideas on entrepreneurship differ from other students’ ideas, often in a fundamental sense, depending on the ethnic, cultural, professional, and personal settings they are used to act in (Druckman & Ebner, 2018). This may be partly culturally determined, which allows for a plea towards using cultural diversity in the classroom as a departure point to experience the implications of differences in the ideas and definitions of entrepreneurship (Rosenthal, 2016; Theroux, 2009).

Rosenthal (2016) succinctly describes the use of cases in education and recommends, for example, that the length and complexity of the cases need to match the level and purpose of the course, as well as dedicated ‘case teachers’ that partly function as coaches. The recognition of the essentially ill-defined nature of management problems and the need for subsequent theorising and conceptualising distinguishes the programmes researched as academic programmes, as opposed to programmes offering professional education at polytechnical universities. Theorising and conceptualising is an academic exercise that may nonetheless inform evidence-based action in management praxis (Rosenthal, 2016) and thus enhance the learning effects of SBEE programmes.

Baggen et al. (2022) stress the importance of increasing the level of complexity and autonomy here as part of experiential learning in entrepreneurship education. The use of well-defined cases, which are defined in a process of co-creation of their definitions, in which autonomy and critical reflection are stimulated, is critically important. Through exercises to define the underlying problem and make the ill-defined problem explicit and thus manageable, students become involved in the design and execution of an intervention in the real world.

Involvement in execution as part of management and entrepreneurship educationProject education is offered in the bachelor's programme, wherein students’ independence in the execution of case-driven research projects and the incorporation of information from industry experts slowly increases. The early bachelor's courses focus on developing an active learning attitude and collaborative competencies through the execution of group assignments, emphasised by Brook et al. (2012) as relevant factors. The interaction with industry experts has only limited implications for the assignments. They primarily function as a source of inspiration. Execution is facilitated throughout the internship at the end of the bachelor's programme.

The execution phase is facilitated throughout the internship and the master's project and thesis at the end of the master's programme. In the master's project and thesis, students contribute to the implementation of their recommendations within the companies themselves, and thus experience this process first hand. They do so in the context of their internship (cf. Scott, 2007). During these internships, students learn to develop recommendations to improve, for example, R&D management and, especially in the six-month master's project, contribute to the implementation of these management solutions as well. They present their results to both the company providing the internship and the university, which allows them to enhance this learning curve on execution.

By the time they start their internship, students have thus acquired a high degree of independence and responsibility in the execution of research projects. Especially in the master's project, the grading depends heavily on dedicated attention to work execution, as a form of ‘deliberate praxis’ that preambles performance by students to create new habits and a certain state of mind as Schindehutte and Morris (2016) discuss, preparing them for their role as a ‘science-to-business professional’ (Retra et al., 2016).

Well-designed project education is crucial here, as Bennis and O'Toole (2005, p. 181) suggest: ‘the best classroom experiences are those in which professors with broad perspectives and diverse skills analyse cases that have seemingly straightforward technical challenges and then gradually peel away the layers to reveal hidden strategic, economic, competitive, human, and political complexities’. In the execution phase, students come to understand, based on experience with innovation processes, that the bias that innovation processes start with exact science is fundamentally flawed, as technical feasibility and market feasibility, as well as the need to create societal value through science, are inextricably intertwined in the processes of innovation introduction and upscaling.

Experiential learning shields the programme from too much emphasis on a (linear) focus on science and technology push, since through its albeit implicit adoption of the four aspects of experiential learning, students quickly learn that there is more to the story than meets the eye in terms of developing and upscaling innovative technological developments and R&D. Throughout the experiential learning process, they experience the messiness of innovation - being in its very essence far from linear and of a far more complex, cyclical, and iterative nature (Berkhout et al., 2010). Based on experiential learning, they start to recognise the discrepancy between a strict ‘science logic’ and an ‘entrepreneurial logic’.