This study offers a thorough examination of viral marketing research during the last two decades to uncover the changing nature of the field. Bibliometric analysis methods are used to analyze 791 peer-reviewed articles written by 1,820 authors and indexed in Scopus and Web of Science (WoS). The findings reveal how viral marketing research evolved over the past two decades, establish vital connections between authors, and uncover themes and trending topics. The study underscores the increasing practical importance of viral marketing by mirroring the substantial growth in research in the field, particularly from 2008 to 2014, with research topics such as Internet marketing, user-generated content, word-of-mouth, and e-word-of-mouth. From 2015 to 2020, viral marketing research exhibited a sustained growth phase, with the number of articles remaining relatively stable, covering topics such as viral marketing, social media, and social networks. In the most recent years, from 2021 to 2023, fluctuations occurred in the volume of articles driven by the focus on online marketing during the COVID-19 pandemic. While overall interest remains robust, these variations might signify a stabilization of the field with the entry of advanced topics such as influence maximization and popularity predictions. Overall, the diverse nature of viral marketing and evolving research landscape were notable across journals of a multidisciplinary nature; this suggests that viral marketing research is likely multidisciplinary, involving components of marketing, social network analysis, computational systems, complex system dynamics, data science, and engineering.

The advent of the Internet has created a novel mode of communication, laying the groundwork for what we now recognize as electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM), endowing it with a pivotal role in the realms of product and service marketing (Shahrinaz et al., 2016). Consequently, the concept of viral marketing blossomed in tandem with the Internet's expansion (Yannopoulos, 2011). Viral marketing, as a phenomenon, materializes when a marketing message is conveyed from one individual to another, leveraging various channels such as word-of-mouth (WOM), email, or websites. This process entails swiftly disseminating messages with an intentional velocity (Ologunebi & Taiwo, 2023; Pandey & Salunkhe, 2022). In this context, brands and promotional content are discussed, and awareness is disseminated through two primary conduits: pass-along emails and conversations within social networks. This approach involves creating captivating or informative messages specifically crafted to be shared exponentially, often through electronic means such as email (Ologunebi & Taiwo, 2023; Pandey & Salunkhe, 2022).

The concept of viral marketing dates back to 1996, when Hotmail, the Internet's pioneering web-based email service, was first utilized (Rodić & Koivisto, 2012). Building upon Hotmail's pioneering strategy, Wilson (2000) delineated six essential steps for effective viral marketing: (1) offering complimentary products or services; (2) facilitating effortless sharing with others; (3) adapting to scalability, from small-scale to extensive outreach; (4) capitalizing on common motivations and behaviors; (5) harnessing existing communication networks; and (6) leveraging the resources of others.

Viral marketing has both advantages and disadvantages. One of its notable advantages lies in its capacity to rapidly reach a substantial online user base in a cost-effective manner (Chaffey & Ellis-Chadwick, 2019). Recent advancements in sentiment analysis have further amplified the potential of viral marketing, allowing for extracting valuable insights from opinions and reviews to optimize marketing campaigns (Khatua et al., 2021). However, acknowledging the drawbacks of viral marketing, which pertain to the initial investment, is crucial. If a viral marketing campaign fails to achieve its intended impact, the resources invested in its propagation may not be recoverable (Chaffey & Ellis-Chadwick, 2019).

Despite the exponential growth in viral marketing research, virtually no comprehensive bibliometric analysis has been undertaken to investigate this burgeoning field within the realm of Internet marketing; thus, this study aims to address this void. It contributes to the field by thoroughly examining the network structure that underpins the body of published research and studies in the domain of viral marketing (Barzilai‐Nahon, 2009; Vos & Heinderyckx, 2015). Moreover, it enriches the emerging body of knowledge of viral marketing across various platforms, encompassing both active and passive viral marketing strategies (Subramani & Rajagopalan, 2003). Our study encompasses a diverse array of platforms where viral marketing has been researched, including social media sites, YouTube, TikTok, email, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, WhatsApp, and WeChat, reflecting the diverse landscape of this subject matter. In the context of this bibliometric study, we specifically aim to find answers to the following research questions:

RQ1: How has research in the field of viral marketing evolved during the last two decades?

RQ2: Who have been the most prominent authors of viral marketing during the past two decades?

RQ3: Which journals serve as primary outlets for the “core” viral marketing research?

RQ4: How has research on viral marketing developed across different scholarly initiatives, institutions, and nations over time?

RQ5: What trends have emerged in viral marketing research?

This paper is organized as follows. In Literature review, we differentiate between viral marketing and similar concepts and review the literature on the construct. In Methods, we provide a detailed description of the methodology used in this study. In Results, we present the results of our research. Finally, in Discussion, we discuss the findings, offer insights for research and practice, and propose directions for future research.

Literature reviewThe uniqueness of viral marketing as a constructResearch on viral communication has sometimes used constructs such as viral marketing, WOM, eWOM, and buzz marketing interchangeably (Bampo et al., 2008; Cruz & Fill, 2008; Petrescu & Korgaonkar, 2011). However, these concepts have qualitative differences that make them independent standalone variables. WOM is defined as interpersonal, oral communication in which the receiver perceives the communicator as being a non-commercial evaluator of a brand or service (Arndt, 1967). Unlike viral marketing, which is intended to be positive, uses Internet-based channels, and is business-generated, WOM can be either positive or negative, is based on consumer-generated opinions, and is uncompensated financially (Arndt, 1967; Derbaix & Vanhamme, 2003). eWOM is defined as “any positive or negative statement made by potential, actual, or former customers about a product or company, which is made available to a multitude of people and institutions via the Internet” (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004, p. 39). In essence, eWOM is similar to WOM but utilizes the viral potential associated with Internet reach. A critical difference between viral marketing and both WOM and eWOM is a causal difference, with viral marketing being an influencing marketing strategy (i.e., a cause) whose outcomes (i.e., effect) are, among other things, WOM and eWOM. Thus, viral marketing refers to the collective activities that marketers utilize to create a viral message regarding their products or services and generate positive WOM and eWOM (Chiu et al., 2007; Ferguson, 2008).

Buzz marketing is defined as “the amplification of initial marketing efforts by third parties through their passive or active influence” (Thomas, 2004, p. 64). One difference between viral marketing and buzz marketing is the communication channel utilized. While viral marketing utilizes electronic mediums, buzz marketing is not limited to the Internet and can harness other channels, such as face-to-face interactions and WOM. However, the main difference between the two constructs is yet again the causal direction, with viral marketing being the strategy used to produce the buzz, which is seen as a consequence of that strategy (Dobele et al., 2007; Petrescu & Korgaonkar, 2011). Confounding viral marketing, with its various other downstream effects, is one of the reasons why the marketing literature on viral communication is ripe with terminological controversies (Bampo et al., 2008; Cruz & Fill, 2008; Petrescu & Korgaonkar, 2011). When it comes to literature reviews such as the work presented here, such confusion can lead to a plethora of problems, such as misrepresenting nomological networks, synthesizing the findings inaccurately, distorting both theoretical and practical implications, and propagating an invalid congruency among clearly distinct constructs, leading to more confusion in the research. Given these distinctions, we limit our bibliometric analysis to viral marketing.

Research on viral marketingA plethora of research investigating viral marketing has shown that understanding the dynamics of user behavior, such as audience targeting, message-forwarding behaviors, and the motivations behind sharing, is crucial for effective campaigns.

Social networks and recommendation systems have become powerful tools for influencing consumer behavior through viral marketing as digitized platforms continue to transform communication and information sharing. Social sharing and virality of online messages are highly dependent on content characteristics. For example, Berger and Milkman (2012) explored the impact of content characteristics on social sharing and virality. Their work revealed that positive content tends to be more viral than negative content. Furthermore, negative emotions associated with deactivation, such as sadness, are negatively correlated with virality, while emotions such as anger and anxiety (activation) have a positive relationship with virality.

The power of viral marketing has increased as social networks and recommendation systems have become practical tools for influencing consumer behavior. For example, Leskovec et al. (2007) analyzed person-to-person recommendation networks and the dynamics of viral marketing. This research examined how user behavior varies across viral marketing target communities and proposed a model for identifying appropriate communities, products, and pricing tiers. The study also found that an excessive viral marketing campaign may reduce the credibility of the product advertised.

In viral marketing campaigns, the global organization of consumers has become a critical factor in shaping consumer decisions. For example, Berger (2014) explored the emergence and importance of audiovisual content in viral marketing and consumer behavior, categorizing it into five groups (impression management, emotion regulation, information acquisition, social bonding, and persuasion) He suggested that audience and communication channels play a pivotal role in modifying the effectiveness of audiovisual content. Furthermore, de Bruyn and Lilien (2008) presented a multi-stage model to study the role of social media marketing in viral marketing campaigns and identified conditions that mitigate its effects. The authors concluded that bond strength increases awareness, cognitive proximity enhances interest, and demographic similarity influences each stage of the decision-making process. Furthermore, in order to achieve success in viral marketing, understanding the dynamics of message forwarding and audience characteristics is critical. In a study of 1259 passed messages, Phelps et al. (2004) found that 40 % of messages were forwarded upon receipt. The study highlighted the importance of carefully analyzing the target group before launching a viral marketing campaign. Ho and Dempsey (2010) examined the motivations behind online content forwarding and identified four primary motivations: The need to belong to a group, individualism, altruism, and personal growth. The research reported that users who are individualistic and altruistic are more likely to forward online content, with the need to fit into a group being a key driver.

Social influence plays a vital role in viral marketing by driving engagement and adoption of products. Aral and Walker (2011) examined the major features associated with viral marketing campaigns and how they can be used to enhance peer influence and social contagion effects. They also distinguished between passive-broadcast and active-personalized viral features, noting their respective impacts on peer influence, user engagement, and product repurchase. Hill et al. (2006) explored network-based marketing and the impact of customer links on sales and provided evidence that network linkage significantly affects the adoption of products and services. The study also highlighted the importance of targeting campaigns using network linkage by understanding the “network neighbors” concept.

In viral marketing campaigns, strategic seeding is essential for maximizing reach and impact. Strategic seeding of information with well-connected individuals can maximize the reach and success of campaigns. For example, Hinz et al. (2011) analyzed seeding strategies in viral marketing campaigns, emphasizing their influence on success. Unlike previous studies, this research conducted small-scale field experiments, concluding that seeding well-connected individuals has the highest success rate. Additionally, well-connected individuals do not necessarily have more influence than less connected ones.

Finally, social media has become crucial for disseminating trustworthy information and medical advice in public health, underscoring the value of monitoring its content. Vance et al. (2009) examined the role of social media as a source of public health information, emphasizing patients’ increasing reliance on social media for medical advice. The research demonstrated the potential of social media in providing practical medical guidance and stated the importance of monitoring dermatologist advertising on social media to maintain professional integrity.

Despite the existing studies, and to the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive bibliometric analysis of viral marketing research exists. Therefore, this study addresses a substantial void in understanding the intellectual structure and emerging trends in viral marketing. Moreover, it addresses the existing gap by encompassing active and passive strategies by analyzing various platforms. Furthermore, the network analysis explores the network structure, which helps us gain insights into the knowledge flow and dynamics of the network. Paving the way for understanding how viral marketing could incorporate novice strategies.

MethodsThis study provides an overview of the refereed paper on viral marketing that is indexed in both Scopus and Web of Science databases using bibliometric analysis methodology. Bibliometric analysis is a quantitative technique used to analyze the literature on a certain research domain and map the relationship between the different constituents in the field (Donthu et al., 2021). The technique also allows researchers to explore the current temporal and institutional structure of the research domain and provide objective definition on the direction of research in the given area of study (Snyder, 2019).

The technique includes four main steps as identified by Mostafa (2022). These four main steps are as follows.

- 1.

Select the research database and identify the search criteria: This is the first step in which the researcher decides on the appropriate database to be used and identifies the search criteria to extract the data related to the given study area.

- 2.

Perform the statistical analysis: The second step is to conduct the preliminary statistical analysis to examine the dataset and compute the different metrics related to the research domain.

- 3.

Develop the bibliometric network: At this stage, the database is used to develop the bibliometric networks and explore the connection and relationship between different research domains in the research area.

- 4.

Explore the conceptual structure and thematic mapping. At this stage, we analyze the conceptual structure of the emerging themes and provide a comprehensive understanding of each area of the research domain.

In the following sections, we explore the above steps in more detail.

Database and document extractionIn line with the methodology layout by Caputo and Kargina (2022), we merged the results from both Scopus and WoS databases, as these databases have different coverage and inclusion criteria based on various research areas (Echchakoui, 2020), which might impact our analysis results. Hence, the results were merged to perform a more inclusive analysis, which would help provide a more informative research finding. Furthermore, to refine our research results, we focused on studies conducted in English and used the search phrase “viral marketing” in the title, abstract, or keywords. The focus on viral marketing allows for a more targeted and in-depth analysis of the concept. While several terms could have increased the study scope, our investigation revealed that viral marketing is qualitatively different from other constructs that have been erroneously used as synonyms. Focusing on viral marketing offers several advantages for scholars and practitioners. It provides quantifiable metrics (through likes, shares, and comments), highlights the speed and scale of viral campaigns, acknowledges their unpredictability, and addresses the field's rapid evolution (Sung, 2021). The search approach is graphically portrayed in Fig. 1.

Initial statistical analysisWe extracted essential bibliographic details from the selected databases and merged them using R-studio and Excel, following the approach recommended by Caputo and Kargina (2022). We manually cross-checked the records to remove duplications. The final dataset included 791 refereed papers published between 1999 and 2024. The data were analyzed using Biblioshiny software. Table 1 presents the key characteristics of our data. According to the table, these articles collectively cited 33,811 references and were authored by 1820 authors. Among the selected papers, 90 manuscripts were single-author documents, and the rest were written by multiple authors, with a collaboration index of 3.22 authors per paper.

Key Data Characteristics.

| Description | Results |

|---|---|

| Main information about data | |

| Timespan | 1999:2024 |

| Sources (Journals, Books, etc.) | 411 |

| Documents | 791 |

| Annual Growth Rate % | 16.94 |

| Document Average Age | 6.66 |

| Average citations per doc | 36.54 |

| References | 33,811 |

| Document contents | |

| Keywords Plus (ID) | 2650 |

| Author's Keywords (DE) | 1906 |

| Authors | |

| Authors | 1820 |

| Authors of single-authored docs | 78 |

| Authors collaboration | |

| Single-authored docs | 90 |

| Co-Authors per Doc | 3.22 |

| International co-authorships % | 0.6321 |

| Document types | |

| Article | 755 |

| article; early access | 1 |

| article; proceedings paper | 2 |

| Letter | 1 |

| Reviews | 32 |

A network may be defined as a structural configuration comprising a group of actors/nodes with certain interconnected actors (Knoke & Yang, 2019). In social network analysis (SNA), such connections are depicted as “edges,” which are essentially lines that connect two interconnected nodes. As more data are collected, the network diagram transforms into a comprehensive social network from a dyad, representing a single connection between two nodes. According to Khan and Wood (2016), SNA techniques, when employed to synthesize current literature from a network standpoint, can unveil latent patterns that greatly facilitate theory development and the exploration of future research domains.

This investigation uses three statistical network parameters to describe the bibliometric networks: node size, density, and length. The size of the node is an indication of the strength of actors/users within the network. The density or concentration reflects the ratio between existing links relative to other potential links in the network. Finally, the length corresponds to the distance between two actors in the network. In our study, we used network analysis to provide a comprehensive overview of the relationship between different actors in the field of viral marketing. To ensure the accuracy of networks, we used a disambiguation algorithm to detect and merge duplicate fields such as authors, universities, or countries, thus ensuring accuracy. To visualize the networks, we used the VOSviewer program (van Eck & Waltman, 2019).

Thematic and conceptual structure mapsThematic/structural map is a structured technique employed to examine the current and emerging concepts in a certain research area based on the analysis of keywords or co-occurring words in the literature (Law et al., 1988). Based on the density and centrality metrics proposed by Callon et al. (1991), thematic mapping integrates concepts from co-word networks and the application of portfolio analysis (Avila-Robinson & Wakabayashi, 2018) to visually present the current dynamics in the field. The usefulness and significance of this diagram have rendered it a prevalent approach in academic research (Khasseh et al., 2017; Lee & Chen, 2012; Zong et al., 2013).

The theoretical structure of the viral market research has been explored using conceptual structure maps by decomposing the research domain into discrete knowledge clusters, with the overarching goal of deriving fresh insights from the data associated with each cluster (Wetzstein et al., 2019). Moreover, temporal analysis was used to systematically examine the evolution of the topic over time, which is consistent with several bibliometric analyses (Cobo et al., 2011b).

ResultsAcademic output and influential authorsWe extracted a corpus of 791 documents related to viral marketing that resulted from the collaborative work of 1820 authors over 25 years, from 1999 to 2024. Extraction was concluded in October 2024.

Research question 1: how has research in the field of viral marketing evolved during the last two decades?Fig. 2 reveals a remarkable annual growth rate of 16.94 % in viral marketing research. However, this growth did not evolve uniformly. The inception of viral marketing research can be traced back to its embryonic stage, denoted by a gradual increase in related articles starting in 1999. The period from 1999 to 2003 serves as a testament to the nascent phase of viral marketing, wherein researchers and marketers alike began exploring this burgeoning concept. The subsequent years, ranging from 2004 to 2007, witnessed a subtle acceleration in the proliferation of published articles, suggesting a considerable interest in research dissemination. A further rise in interest in the subject was witnessed as the years 2006 and 2007 heralded a revival in research output. The interval from 2008 to 2014 proved pivotal for viral marketing research, marked by an exponential surge in published articles. This surge aligned with the increasing prominence and efficacy of viral marketing campaigns in the corporate sphere, especially between 2011 and 2014, when the number of articles more than doubled. From 2015 to 2020, viral marketing research exhibited a phase of sustained growth, with the number of articles remaining relatively stable. This constancy might indicate that viral marketing has advanced from an emergent concept to a mature and extensively studied field. In the most recent years, from 2021 to 2023, fluctuations occurred in the volume of articles peaking in 2020. The onset of COVID-19 forced consumers to work and study remotely, which meant that marketers aggregated heavily toward strategies that targeted this continuously online base. This and the heated discussion regarding fake news and misinformation represented fertile ground for researchers investigating viral communication in general (Al Hajj et al., 2024) and viral marketing in particular. While overall interest remains robust, these variations might signify a field stabilization.

Research questions 2 and 3: primary outlets journals for the “core” viral marketing research and prominent authors during the past two decadesThe data presented in Table 2 present an overview of the top 10 relevant sources publishing viral marketing research. This compilation reveals the considerable influence of specific journals, suggesting their potential influence on shaping the discourse on viral marketing—specifically, Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, Social Network Analysis and Mining, IEEE Access, and IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems published 21, 18, 17, and 17, respectively. This higher publication volume within these journals indicates a focus on viral marketing and provides readers with a valuable list of sources that they can tap into for their research.

Top 10 Viral Marketing Research Sources by Number of Publications.

| Sources | Articles |

|---|---|

| Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications | 21 |

| Social Network Analysis and Mining | 18 |

| IEEE Access | 17 |

| IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems | 17 |

| Information Sciences | 15 |

| Ieee Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering | 14 |

| Knowledge-Based Systems | 11 |

| Expert Systems With Applications | 10 |

| Journal of Interactive Marketing | 9 |

| Plos One | 9 |

What is particularly striking is the diverse spectrum of disciplines represented within this list, ranging from physics to computer science, marketing, and beyond. This diversity underscores the multidisciplinary nature of viral marketing as a research topic. Journals such as IEEE Access and IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems bring into focus the convergence of technology, data, and marketing, shedding light on the technical intricacies of viral campaigns and their impact on social systems. The consistent prevalence of Social Network Analysis and Mining Journal underscores the pivotal role of social network dynamics in the landscape of viral marketing. Moreover, journals such as IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering underscore data science's pivotal role in viral marketing research, highlighting the critical significance of data analysis and information extraction in advancing our understanding of this phenomenon. Conversely, journals such as the Journal of Interactive Marketing, Knowledge-Based Systems, and Expert Systems with Application appear to be geared toward a business and marketing readership, illuminating the practical and strategic dimensions of viral marketing research.

To gain further insights into the influence of these journals, one can turn to Bradford's Law (Bradford, 1934), which discerns a hierarchy of productivity among scientific journals. Fig. 3 illustrates the application of Bradford's Law in the context of viral marketing research. The graph shows that a select few journals dominate the “core zone,” including Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, Social Network Analysis and Mining, IEEE Access, Ieee Transactions on Computational Social Systems, Information Sciences, IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, Knowledge-Based Systems, Expert Systems With Applications and Journal of Interactive Marketing. These journals are recognized as the principal outlets for disseminating seminal research in the core domain of viral marketing, further underscoring the multidisciplinary nature of research studies in the field. These journals span disciplines such as mathematics and statistics, social network analysis, computer science, data science, and business and marketing.

Bradford's Law for Most Prominent Sources*.

Table 3 provides a compendium of the most highly cited articles in viral marketing research, underscoring their profound influence on the discourse in this field. The table illustrates an overview of the most influential articles in viral marketing research, which is vital for showcasing the dynamic progression of knowledge and focus within the field. The research progresses from identifying critical factors to exploring their nuanced interactions. Among these seminal works is the research conducted by Berger and Milkman (2012), published in the Journal of Marketing Research, which has garnered 1997 citations. This study found that positive content exhibits a heightened tendency to reach customers compared to negative material. Additionally, it highlighted the pivotal role played by emotions, characterized by high arousal, such as amazement, rage, and anxiety, in augmenting the likelihood of content going viral. The article by Leskovec et al. (2007), published in ACM Transactions on the Web, amassed 1404 citations. In this paper, the authors found that recommendations exhibit limited efficacy in driving purchasing decisions, while viral marketing within specific communities and product categories can prove exceedingly efficient. Berger's (2014) work, cited 991 times, examined the ubiquity and significance of WOM and emphasized the need for deeper exploration into the factors and determinants that shape this phenomenon. De Bruyn and Lilien's (2008) study, cited 614 times, affirmed that the characteristics of social connections significantly influence recipients’ behaviors. Phelps et al.’s (2004) article, with 601 citations, highlighted the pivotal role played by individual motivations and behaviors in the realm of viral marketing. It underscored the importance of comprehending the psychological underpinnings that drive viral content dissemination. Overall, the evolution of research illustrated in Table 3 presents the shift from the initial explorations of individual motivations and social networks to a sophisticated understanding of the psychological and emotional motives of viral marketing.

Most Globally Cited Viral Marketing Articles.

| Paper | Total Citation | TC per Year | Normalized TC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berger (2012), Journal of Marketing Research | 1997 | 166.42 | 9.79 |

| Leskovec (2007), ACM Transactions on the Web | 1404 | 78.00 | 8.70 |

| Berger (2014), Journal of Consumer Psychology | 991 | 90.09 | 18.80 |

| De Bruyn (2008), International Journal of Research in Marketing | 614 | 36.12 | 4.46 |

| Phelps (2004), Journal of Advertising Research | 601 | 28.62 | 2.68 |

| Huberman (2009), First Monday | 579 | 36.19 | 3.68 |

| Aral (2011), Management Science | 571 | 40.79 | 5.32 |

| Hinz (2011), Journal of Marketing | 474 | 33.86 | 4.42 |

| Golovin (2011), Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research | 432 | 30.86 | 4.03 |

| Katona (2011), Journal of Marketing Research | 422 | 30.14 | 3.94 |

| Kempe (2015), Theory of Computing | 422 | 42.20 | 10.25 |

| Ho (2010), Journal of Business Research | 372 | 24.8 | 4.79 |

| Arora (2019), Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services | 350 | 58.33 | 10.33 |

| Vance (2009), Dermatologic Clinics | 348 | 21.75 | 2.21 |

| Thackeray (2008), Health Promotion Practice | 329 | 19.35 | 2.39 |

| Shareef (2019), Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services | 308 | 51.33 | 9.09 |

| Kiss (2008), Decision Support Systems | 307 | 18.06 | 2.23 |

| Dobele (2007), Business Horizons | 292 | 16.22 | 1.81 |

| Narayanam (2011), IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering | 284 | 20.29 | 2.65 |

| Aral (2014), Management Science | 282 | 25.64 | 5.35 |

| Bampo (2008), Information Systems Research | 270 | 15.88 | 1.96 |

| Hill (2006), Statistical Science | 268 | 14.11 | 2.51 |

| Kaplan (2011), Business Horizons | 267 | 19.07 | 2.49 |

| Landherr (2010), Business & Information Systems Engineering | 266 | 17.73 | 3.43 |

| Subramani (2003), Communications of the ACM | 266 | 12.09 | 1.42 |

| Bonchi F., 2011, ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology | 263 | 18.79 | 2.45 |

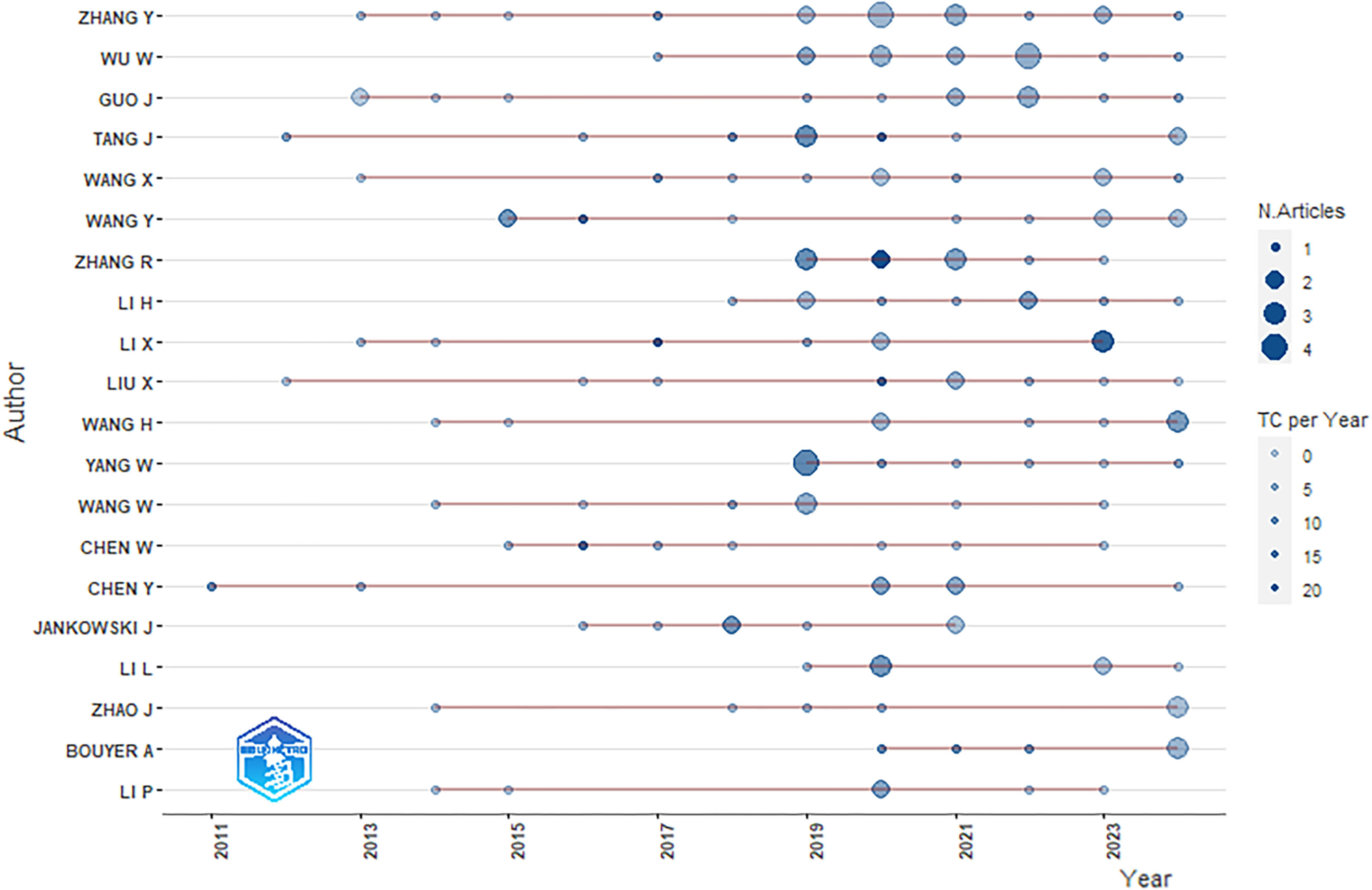

Author's dominance over time is used to assess writers’ prominence in the academic landscape (Kumar & Kumar, 2008). In scholarly literature, this metric is extensively used (Elango & Rajendran, 2012; Firdaus et al., 2019; Hussain et al., 2023). Fig. 4 presents a visual representation of the ebb and flow of dominating authors in the field over time. Y. Zhang held sway from 2013 through 2023, and Y. Chen exhibited dominance from 2011 to 2023. However, the landscape also witnessed the rise of emerging authors who have carved their niche in the discipline, including W. Wu (2017–2022), R. Zhang (2019–2022), and L. Li (2019–2023); this suggests the dynamic nature of author dominance in viral marketing research. In the realm of bibliometric analysis, Lotka's law is a well-established metric that assesses the “Evenness/Concentration of Authors’ Contribution” (Merediz-Solà & Bariviera, 2019). This metric was first proposed by Lotka (1926), who posited that “the number of authors producing a certain number of articles is in a ratio which is fixed, usually 2, to the number of single-article authors.” Our findings suggest the applicability of Lotka's Law in the context of viral marketing research (β = 4.7; K-S Two-Sample Test p = 0.2). This confirms the systematic distribution of authorship contributions in the field and emphasizes the balanced interplay of authors’ productivity.

Network analysesCo-citation networksFig. 5 visually portrays the viral marketing authors’ co-citation network, delineating four distinct clusters using color coding. The red cluster encompasses authors such as J. Leskovec, W. Chen, and Y. Wang. An exploration of this graph reveals several important insights. For example, upon scrutinizing the node sizes within the network, we observe that Y. Wang occupies a central position in the network, which points to substantial influence in the realm of viral marketing research. Such noteworthy authors can be likened to core actors in a network (Lin & Himelboim, 2019) as they play a pivotal role in shaping interaction dynamics and information dissemination within the research network. Bakshy et al. (2011) argued that relevant authors are well positioned to initiate conversations and stimulate discussions, thereby disproportionately influencing information diffusion.

The co-citation network also unveils the proximity of particular nodes, representing a pronounced “homophily effect.” Homophily, rooted in the concept of “similarity breeds connection” (McPherson et al., 2001), is observed when actors in a shared intellectual space engage in discussions centered around common interests or shared research topics (Findlay & Janse van Rensburg, 2018). Jiang et al. (2019) noted that homophily in bibliometric networks can often manifest thematic or disciplinary affinities; for instance, the proximity of the nodes representing Y. Wang and W. Chen suggests a potential homophily effect, underscoring their shared focus on collaborative knowledge building in the context of viral marketing. When clusters in a network lack connections, they create structural holes, which are visible as white spaces between nodes and clusters (Haythornthwaite, 1996). Haythornthwaite (1996) suggests that researchers can exploit structural holes by using research papers that bridge disparate clusters within the network. These papers serve as critical links, connecting otherwise isolated knowledge communities. Authors who adeptly bridge these structural holes become information brokers, facilitating connections between distinct groups within the network. This pivotal role confers a “structural advantage” upon them as they enhance the flow of knowledge and interactions across the network, strengthening the fabric of scholarly discourse (Burt, 1999).

Fig. 6 depicts the source's co-citation network in viral marketing research. The graph distinctly delineates seven journal co-citation clusters, each representing a unique area of scholarly discourse. For example, the green cluster stands out and comprises journals such as Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, Physical Review E - Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics, Expert Systems with Applications, and Nature. This cluster focuses on doing viral marketing research using a knowledge-based approach in the form of expert and knowledge-based systems. The blue cluster encompasses journals that focus on management science. Prominent members of this cluster include Management Science, Marketing Science, and the American Journal of Sociology. In the figure, the red cluster emerges as the most important cluster and includes several prominent marketing journals such as the Journal of Marketing Research, Journal of Consumer Research, Journal of Consumer Marketing, and Journal of Interactive Marketing.

The “core journals” publications cluster within the network, indicating a concentration of studies exploring common thematic and methodological perspectives. Conversely, articles originating from journals or fields with fewer thematic similarities tend to be dispersed throughout the network. This observed pattern implies a tendency toward cluster specialization and knowledge concentration within each group, confirming limited interaction between these clusters; this aligns with the concept of “orthodox core-heterodox periphery” (Glötzl & Aigner, 2018). Each group is formed by a few highly cited “orthodox journals,” with “heterodox journals” occupying the periphery. This arrangement suggests a distinct hierarchy in terms of influence and engagement within the network. The co-citation network offers a nuanced insight into the interrelationships among journals in the field, unveiling the thematic focuses of different clusters and their patterns of interaction.

Collaboration networksResearch question 4: the development of viral marketing research across different scholarly initiatives, institutions, and nations over timeFig. 7 shows a visual representation of the author's collaboration network within the realm of viral marketing research. This graph provides valuable insights into the collaborative dynamics among researchers. In the graph, the size of each node is directly proportional to the number of publications attributed to the author, while the thickness of the links reflects the number of joint publications. The graph signals limited collaboration among authors in the field of viral marketing research, and it shows five major research communities, each distinguished by a different color. For instance, the Green cluster features authors such W. Yang, Y. Zhang, H. Wang, and X. Li. X. Wang and Y. Chen predominantly steer the Red network, while W. Wang and X. Liu lead the Blue cluster. Conversely, Y. Wang, W. Chen, and Y. Li dominate the Yellow cluster. Finally, R. Zhang, J. Tang, and H. Li equally dominate the purple cluster, with Z. Zhao having the lowest contribution to that cluster. These communities reflect thematic and collaborative alliances among researchers in viral marketing research. However, the fragmented nature of the network signifies that the level of collaboration within the field remains somewhat limited. Thus, highly productive authors in the field often engage in close-knit collaborations while having fewer contacts that extend beyond their scientific circles. While collaboration within these clusters is vibrant, fostering innovation and knowledge exchange, the overall network's sparsity indicates the presence of unexplored opportunities for broader interdisciplinary collaboration and knowledge dissemination in the field of viral marketing research.

Moreover, Fig. 8 offers a comprehensive visual representation of the collaborative network among institutions engaged in viral marketing research. In this graphical representation, the size of each node corresponds to the institution's publication output, while the thickness of the connecting links indicates the strength of their collaborative ties. The network reveals eight major research communities, each distinguished by distinct colors. For example, the Blue cluster unites academic institutions such as the University of Texas at Dallas in the United States of America, the National University of Singapore in Singapore, and Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. Conversely, the Red cluster comprises institutions such as the University of Maryland, University of Technology, Delhi Technological University, and University of Electronic Science and Technology of China. The Purple cluster encompasses institutions such as the University of California, Carnegie Mellon University, and the National University of Defense Technology, while the Green cluster includes Deakin University in Australia and Tsinghua University in China. This network configuration appears to align with a locally centralized and globally discrete model of institutional collaboration (Zou et al., 2018). Notable exceptions, however, can be observed in the Blue cluster, where institutions such as the University of Texas at Dallas in the United States of America, Beijing Normal University in China, and the National University of Singapore in Singapore engage in cross-continental collaborations. These instances of intercontinental cooperation stand out as examples of research institutions transcending geographic boundaries. A closer look at the clusters formed reveals that most institutional collaborative initiatives are based on geographic proximity, linguistic similarity, or cultural affinity.

Furthermore, Fig. 9 depicts the collaborative network among countries engaged in viral marketing research. This graphical visualization shows each country's publication output by the relative size of each node, while the links between them represent the level of cooperation among countries. The graph shows that the United States and China are the most prolific countries in viral marketing research, displaying a robust level of cooperation with China and India. Additionally, it shows instances of lesser cooperation, such as the collaboration between researchers from Poland and other countries such as Denmark and the Netherlands. This pattern of cooperation among countries is further illuminated by Fig. 10, which visually represents the collaboration patterns in viral marketing research on a global scale. In this illustration, the intensity of color directly corresponds to the volume of publications, and the pink lines signify collaborative relationships between nations. This graphic visualization offers a global perspective on the collaborative landscape in viral marketing research, highlighting the varying degrees of interaction among countries and the potential for further international collaboration in this field.

Keywords and co-occurrence networksThe utilization of keywords is a common practice in scholarly research to encapsulate the essence of a paper, primarily owing to their abstract nature (Chen et al., 2008). In Fig. 11, we present a word cloud of the authors’ provided keywords, which serves as a succinct and informative tool to condense textual data. The significance of each word within the cloud is determined by its size and proximity to the center, allowing for quick identification of the most relevant and frequently used terms (Liao et al., 2019). From this graph, we observe that specific keywords prominently feature in the research landscape: “viral marketing,” “social network,” “influence maximization,” “word of mouth,” and “social media.” To gain deeper insights into the co-occurrence of keywords within the same documents, we generated a network of viral marketing keywords co-occurrences using the author-provided keywords and presented them in Fig. 12, which reveals two primary clusters. The first cluster, depicted in red, centers around viral marketing and encompasses terms such as “word of mouth” and “social media.” This thematic grouping underscores the interconnectedness of concepts related to viral marketing, with an emphasis on the propagating information in the form of eWOM through social channels such as social media. In contrast, the second cluster, portrayed in blue, pertains to the domain of social networks. In this cluster, keywords such as “social network” and “influence maximization” are predominant. This cluster elucidates the research focus on understanding the dynamics of influence and how it spreads within social networks. These social network and viral marketing clusters exhibit a strong relationship, as evidenced by the thickness of the relationship between viral marketing, social network, and influence maximization. By employing these visual tools, we can efficiently distill the central themes and connections within the domain of viral marketing research, offering a concise overview of the prevailing topics and their interrelationships.

Trending topics and themes in viral marketing researchResearch question 5: what trends have emerged in viral marketing research?Fig. 13 is a graphical representation of the trending topics within the domain of viral marketing research across time. This graph unveils a discernible shift from established viral marketing topics, such as “internet marketing” (prominent between 2008 and 2016) and “marketing” (notable from 2009 to 2016), toward emerging themes like “viral marketing” (prominent between 2013 and 2021), “social networks” (gaining prominence from 2018 to 2021), and “influence maximization” (dominating the period from 2018 to 2021). These evolving topics can be aptly characterized as “trending topics” or “hotspots” within the realm of scholarly publications focusing on viral marketing. The emergence of such topics can be interpreted as a reflection of the dynamic and evolving nature of research within the field. It aligns with the notion that trending topics typically signify themes or hotspots undergoing rapid development and transformation within a particular research domain (Chen et al., 2012; Neff and Corley, 2009; Van Eck and Waltman, 2014). Sudden bursts or surges in keywords can also indicate “potential fronts,” denoting research areas that are gaining traction and evolving (Mostafa, 2023). Scholars have suggested that the body of knowledge within a given discipline frequently takes the form of a series of issues that initially appear, become significant over time, and gradually fade (Colicchia et al., 2019; Qian et al., 2019).

Conceptual structure mapBuilding upon the methodology introduced by Demiroz and Haase (2019), we conducted a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) to unravel the conceptual structure of keywords associated with viral marketing research spanning a 24-year period. Fig. 14 provides a visual representation of the results, offering a glimpse into the intellectual landscape of the field during this time frame. In this graph, the proximity of dots indicates the similarity of the profiles they represent, while clusters of dots signify discriminating profiles (Wong et al., 2021). The results of MCA analysis show that three distinct clusters have emerged as the intellectual structure of viral marketing research. The preeminent cluster, denoted by the color blue, is characterized by keywords that underscore the informational significance of viral marketing. These keywords include “word of mouth,” “social networking sites,” “viral marketing,” and “internet marketing.” For instance, Zhou et al. (2017) found that aligning content delivery with market trends and targeting users with extensive social connections can effectively attract website visitors through WOM communication. Chiosa and Anastasiei (2017) demonstrated that negative messages on social media can alter brand perception, generate negative WOM, and impact future purchase intentions. Pedersen et al. (2014) emphasized the influence of eWOM communication among friends and peers on consumer behavior, noting that negative WOM is often perceived as more trustworthy than positive messages.

The second cluster, depicted in red, encompasses keywords such as “community structure” and “popularity prediction.” This cluster emphasizes the importance of network structure and social reinforcement in the diffusion of information. For instance, Sassine and Rahmandad (2023) argued that random networks are more effective for complex contagion, where multiple reinforcements are necessary for adoption. Conversely, Tur et al. (2014) highlighted the impact of social reinforcement on diffusion, showing that it can spread ideas that might not have diffused otherwise. The network's structure—especially small-world networks with low rewiring probability—can amplify the effect of social reinforcement. Nagata and Shirayama (2012) analyzed the relationship between network structure and information diffusion dynamics, providing a framework for generating networks with different structures. These findings underscore the significance of considering network structure and social reinforcement when investigating the diffusion of socially reinforced information.

The third and smallest cluster, depicted in green, appears to revolve around social contagion and peer influence topics. Keywords within this cluster include “peer contagion,” “information system,” and “peer influence.” For instance, Dishion and Tipsord (2011) highlighted how peer contagion can lead to increased aggression and problem behaviors in children and adolescents. Lei and Lehmann-Willenbrock (2014) explored the influence of peer effect on individual emotions and performance in teams, emphasizing both the benefits and costs of peer affective influence. Dimant (2016) investigated the drivers and mechanisms of peer effects, revealing that anti-social behavior is more contagious than pro-social behavior and that social identification with peers plays a role in the contagion of anti-social behavior. Braha and de Aguiar (2016) focused on social contagion in the context of voting behavior, proposing a model to disentangle peer influence from external influences. These studies collectively contribute to our understanding of how social contagion and peer influence shape various facets of human behavior and decision-making.

Thematic mapsFig. 15 illustrates the thematic/strategic map of viral marketing. In this diagram, a dashed line bisects the image into four quadrants, each representing a separate thematic category based on the average values of both axes. The size of the bubbles in the graph is directly proportional to the frequency of appearance of specific keywords in academic publications. As Cobo et al. (2011a) have described, the first quadrant, situated in the top right, depicts high density and centrality. This configuration indicates that the themes within this quadrant are well established both internally and externally and earn the label of “motor themes.” Moving to the second quadrant, positioned in the top left, we find themes characterized by high density but low centrality. These themes exhibit robust internal connections but limited external influence, which earns them the designation of “highly-developed-and-isolated themes.” In the third lower-left quadrant, we encounter themes marked by both low density and centrality. These themes possess weak internal and external connections and are therefore referred to as “emerging-or-declining themes.” Last, the fourth quadrant, found in the lower right, comprises themes with low density and high centrality. These themes exhibit limited internal development but hold significant external connections, which makes them “basic-and-transversal themes.”

Within the upper-right quadrant of motor themes, we identify themes that boast high centrality and density. These themes are not only well developed but also exert a substantial influence on the research domain. Themes such as “viral marketing,” “social media,” and “word-of-mouth” have maintained their significance and breadth over two decades of scholarly publications in viral marketing. For example, the seminal work conducted by Leskovec et al. (2007) explored the dynamics of viral marketing in person-to-person recommendation networks using a network consisting of 4 million people who had made 16 million recommendations for half a million products. The study established how networks grew over time and explored a model that successfully identified communities, products, and effective pricing categories that could be used in viral marketing (Leskovec et al., 2007).

In the upper-left quadrant, keywords such as “mobile viral marketing,” “consumer behavior,” and “technology acceptance model” denote a niche theme. In the areas of mobile viral marketing and technology acceptance model and from a consumer behaviors perspective, Hendijani Fard and Marvi (2020) explored the acceptance of mobile viral marketing messages from the two main constructs of technology acceptance model, namely perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, and their effect on attitude and intention of purchasing mobile application. The study tried to explore the effect of viral marketing messages from three intertwined aspects, namely, quality of the message, argument quality, and source credibility, in which all three constructs significantly affect perceived usefulness, and argument quality affects perceived ease of use, with both significantly affecting intention to purchase (Hendijani Fard & Marvi, 2020). On the consumer behavior aspect, several studies have raised concerns about the ethical use of viral marketing and how it might encourage consumers to make recommendations from their contacts by sharing information using their mobile technology, which might raise ethical concerns. Conversely, for users, distinguishing whether the viral marketing message comes from their peers’ original content or from firm-generated viral marketing activities is hard (Schulze et al., 2014). While internally interconnected, these keywords lack substantial external connections and remain of limited importance in the field.

Keywords situated in the lower-left quadrant of emerging or declining themes, such as “target set selection,” “approximation,” and “dynamic monopolies,” suggest emerging themes or hotspots in viral marketing scholarly research. For example, Shakarian et al. (2016) have explored studies in target-set selection by using the tipping model in social networks and investigated how a set of initial “seeds” can guarantee the spread of, for example, general-purpose social media to the entire network (Shakarian & Paulo, 2012).

Finally, the lower-right quadrant encompasses basic themes, featuring terms such “influence maximization,” “social networks,” and “social influence.” These themes are foundational and vital for advancing scholarly research in the realm of viral marketing. Research on influencers has gained much attraction. Leung et al. (2022) proposed ways that would aid in developing a theory of online influencer marketing (OIM); they proposed six novel propositions illustrating the benefits such as targeting, positioning, creativity, trust, and potential threats, namely content control and customer retention. Furthermore, they proposed effective strategies for managing OIM (Leung et al., 2022). As shown by this work, these themes are still in the process of inception and development and are slowly gaining external recognition.

DiscussionThis research was motivated by the desire to visually represent and map the conceptual and structural knowledge of viral marketing research, concurrently examining the evolution of scholarly publications and revealing the intellectual core of this domain. Therefore, using novel and robust bibliometric network techniques, we analyzed 791 documents on viral marketing indexed in Scopus and WOS spanning two and a half decades and authored by 1820 authors. By employing a bibliometric methodology, we benefit from the objective presentation of the results and real data, as opposed to subjective techniques, which would entail the risk of sample selection bias that may be found in traditional research methods (Linnenluecke et al., 2020). Our objective is to use SNA to thoroughly examine viral marketing research and overcome the shortcomings of conventional research methods. Consequently, we identified a key group of influential scholars, outstanding journals, and major trends that have contributed to the transformation and evolution of the field.

By mirroring the substantial growth in related research, particularly between 2008 and 2014, we revealed the increasing practical importance of viral marketing. Furthermore, we highlight the notable multidisciplinary nature of the journals, which demonstrates the diverse nature of this research and its evolving landscape. For instance, IEEE Access and Information Sciences dominates the dissemination of influential work, underscoring the multidisciplinary nature of viral marketing. Consequently, involving the components of marketing, social network analysis, computational systems, data science, and data engineering suggests that viral marketing research is likely to be interdisciplinary. The findings also reveal seminal works shaping courses in viral marketing, emphasizing positive emotions, social networks, and targeted strategies (e.g., Berger & Milkman, 2012; Leskovec et al., 2007).

Collaborative networks provide significant insights into the dynamics and patterns of knowledge production and flow in viral marketing research. For example, Zhang and Chen presented the author-dominant patterns. Furthermore, collaboration is still restrained and is mostly seen across similar geographic or cultural groups. This finding suggests a lack of potential for novel ideas and methodologies, as indicated by the fact that viral marketing research is predominantly confined to smaller clusters. Moreover, we conclude that geographic proximity and cultural and linguistic similarities are key determinants of collaborative work in the field, as demonstrated by a locally centralized collaboration model among institutions. Based on these findings, we suggest broadening the scope of viral marketing research and providing externally valid outcomes applicable across diverse markets. The findings of the collaborative network analysis have considerable implications for shaping future research endeavors toward a more integrated, innovative, and impactful research landscape.

The keywords and co-occurrence networks show that the main keywords include “viral marketing,” “social networks,” and “influence maximization,” while trending topics appear to be shifting toward “complex networks,” “community structure,” and “influence maximization.” This observation signals a change in the research focus toward more complex aspects and technical areas of viral marketing, such as algorithmic and data-driven approaches. Therefore, we explored studies related to keywords such as influential nodes to optimize the influence of viral messages on online networks. The application of this strategy, analyzing trending topics and thematic evolution, highlights the need for continuous exploration to bridge the gap between niche and mainstream research areas. Building on established knowledge and leveraging foundational concepts, these findings address the challenges and novel opportunities in the evolving field of viral marketing.

The conceptual structure of the field is represented by three main thematic clusters: information aspects, network structures, and social contagion. Finally, through historiographic analysis, we identified influential studies clustered around 2012–2016 and 2018. This finding emphasizes the most important themes identified, namely consumer engagement, humor, multimedia, and the prediction of viral success.

Finally, this comprehensive bibliometric study on viral marketing research provides evidence of the field's evolution, key players, and dominant themes. The dynamic and evolving nature of this domain is underscored by the emergence of influencer marketing, the growth of technical research areas, and the potential for broader collaboration. Therefore, we present valuable insights for viral marketing professionals to use our findings regarding these trends. Furthermore, when marketers understand the core themes that influence authors and key journals, marketing campaigns that leverage social networks, emotions, and targeted messaging can be more effective. Both academics and practitioners will find this study useful, as it provides insight into the future of viral marketing research and practice.

Implications, limitations, and future researchThis study contributes to the development of more focused and potent viral marketing strategies by identifying key trends, influential actors, and prospective research gaps. Accordingly, the focus of research has shifted from foundational concepts, such as “internet” and “marketing” to more specialized areas such as “popularity prediction” and “influence maximization.” This observation contributes toward a more critical understanding of maximizing and effectively deploying the viral phenomena that seemingly emerge from the viral marketing theory. Furthermore, emerging themes such as “influence propagation,” “influence diffusion,” and “social influence” present the value of the developed theoretical frameworks. Conversely, new areas of research that have been developed include mobile viral marketing, and the technology acceptance model has reacquainted with the tendency to apply the technology acceptance model in assessing the acceptance of the viral marketing strategy in the mobile context (Hendijani Davis, 1989, Hendijani Fard & Marvi, 2020).

Investigating viral marketing using bibliometric analysis is vital to the academic understanding of the field and has critical implications for marketing strategies. For instance, identifying key journals, influential authors, and trending topics offers practitioners valuable opportunities. Marketers can gain valuable guidance when applying these insights towards their viral marketing efforts through influential publications and thought leaders. In fact, marketers can determine and include key influencers, as evident from themes such as “target set selection” and “dynamic monopolies” to maximize the impact and reach of their viral marketing campaigns. Consequently, this study emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and an integrated view of viral marketing.

Despite the contributions of this study, it has some limitations. In contrast to Holub and Johnson (2018), our study exclusively utilizes two primary databases: Scopus and WoS. Therefore, this might have led to more cautious citations and relationship counts when compared to alternative sources such as Google Scholar. Nevertheless, most documents cited in other sources, including WoS, are also indexed by Scopus, which is an ambitious quality control effort (Gavel & Iselid, 2008). However, Google Scholar allows citations from blogs, syllabi, unpublished presentations, and other similar web resources, in contrast to other search engines (Neuhaus et al., 2006). Future studies should examine the means of following up on our findings by including additional datasets in their analyses. Furthermore, the limitation of our search for articles that were published exclusively in one language, English, may restrict the extent of our coverage. Despite being similar to other studies (e.g., Qian et al., 2019) using only English language publications, future research should consider the inclusion of publications in other languages to evaluate the applicability of our findings across multiple languages. For instance, publications from highly productive countries, such as China.

Several recommendations should be considered for future studies. Our study is an extensive bibliometric analysis of viral marketing publications published >25 years ago. However, future studies could explore the latent patterns in textual viral marketing data using a topic modelling technique, as is evident in Chen et al. (2020). It may be useful to apply this methodology to uncover hidden thematic patterns in the content of articles, contributing to the understanding of the area. However, the approach we employed— the co-citation network method, likely used consistently by other scholars in the field —may conceal important linkages, according to Skupin (2009), who proposed self-organizing maps and continuous spaces as potential solutions. Therefore, future research could cross-validate the results of the co-citation techniques used in the present study using alternative methods to confirm the results and ensure an understanding of the intellectual terrain within the subject area.

Finally, our findings provide a valuable map of the scholarly landscape of viral marketing for academics and practitioners interested in this field. Further studies should discuss the particular mechanisms and actions scholars, and educational institutions use to influence the field's discourse. Extending the analysis of the antecedents of overall collaboration by including cultural and geographical factors may contribute to a deeper understanding of the dynamics of viral marketing research.

CRediT authorship contribution statementOmer Gibreel: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Mohamed M. Mostafa: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Conceptualization. Ream N. Kinawy: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Investigation. Ahmed R. ElMelegy: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Raghid Al Hajj: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Dr. Omer Gibreel is an Assistant Professor in Management Information Systems at Gulf University for Science and Technology. He has previously held positions as a former Dean of Business Administration and Assistant Professor at the National University Sudan and an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Khartoum University. Omer has published his work in prestigious journals such as Electronic Commerce Research and Application, Sustainability Journal, and the World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management, and Sustainable Development. He has also presented his work at international conferences such as the International Conference on Electronic Commerce and the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS).

Mohamed M. Mostafa has received a Ph.D. in Business from the Manchester Business School, the University of Manchester, UK. He has also earned an MS in Applied Statistics from the University of Northern Colorado, USA, an MA in French Language and Civilization from Middlebury College, USA, an MA in Social Science Data Analysis from Essex University, UK, an MA in Translation Studies from Portsmouth University, UK, an MSc in Functional Neuroimaging from Brunel University, UK and an MS in Affective Neuroscience from the University of Maastricht/the University of Florence. Currently, he works as a Full Professor at GUST, Kuwait. He has published over 130 research papers in several leading academic peer-reviewed journals.

Dr. Ream Kinawy, a Lecturer of Marketing at the College of Business Administration at Gulf University for Science and Technology. Her research focuses on impactful topics such as national identity, cultural preference, consumer behaviour, green marketing and values orientations. She is active in prestigious conferences such as British Academy of Management and European Marketing Academy. Her research delves into fundamental topics that provide significant contribution for scholars and practitioners.

Ahmed ElMelegy is an Assistant Professor of Operations Management at the College of Business Administration at Gulf University for Science and Technology. He holds a B.Sc. in Construction Engineering from Ain Shams University, an MBA with a specialization in Operations Management from the American University in Cairo, and a PhD. in Management Sciences with a specialization in Operations management from Illinois Institute of Technology. His teaching interests include Operations Research, Operations Management, Supply Chain Management, and Business Statistics. Ahmed's research focuses on Service management & E-Services, Technology Management, Scheduling Algorithms, and Queuing Models.

Dr. Raghid Al Hajj is an Assistant Professor of Management at the Gulf University for Science and Technology (GUST) in Kuwait and heads its Academic Hub for Entrepreneurial Advancement and Development (AHEAD). His research interests include work stress, emotions, leadership, psychophysiological processes, Research Methodology, and Business education. Dr. Al Hajj has published in top tire journals, including the Journal of Organizational Behavior, Academy of Management Learning and Education, Hormones and Behaviors, and Review of Managerial Science.

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.