Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is microscopic damage to the white matter of the corpus callosum and brain stem, and is one of the leading causes of loss of consciousness and a vegetative state in traumatic brain injuries (TBI). Isolated cases of DAI have been identified in the context of hypoxia.1

DAI's clinical presentation usually relates to its severity, with a broad spectrum of symptoms ranging from headaches or vomiting to neurological deficits, loss of consciousness, or coma.

Despite the fact that the COVID-19 pathology is mainly respiratory and cardiovascular, patients with severe SARS-CoV 2 infection are predisposed to present a neurological pathology, including encephalopathy, strokes and myopathy.2 Cerebral hypoxia within the context of severe pneumonia or immune mediated injury as the main mechanisms, have both been described.3

We present the case of a 35-year-old woman , who was admitted to the ICU with respiratory failure in March 2020, with no known environmental epidemiology or previous infection. When the emergency ambulance service arrived at the patient's home, she presented oxygen saturation < 50%, BP 80/45 mmHg, HR 96 bpm and GCS 3/15. They proceeded to orotracheal intubate her and she was transferred to our centre. A SARS-CoV 2 PCR test resulted positive, and a chest x-ray showed images compatible with bilateral COVID-19 pneumonia. The patient's lab tests upon admission, highlighted: leukocytes 17.48 × 103/μL (N 83.5%, L 10.0%), lymphocytes 1.00 × 103/μL, fibrinogen 596 mg/dL, d-dimer 6070 ng/mL, C-reactive protein 191 mg/L, ferritin 403 ng/mL, with no other significant alterations.

Treatment was started with hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, dexamethasone and low-molecular-weight heparin at therapeutic doses of 1.5 mg/kg/day (enoxaparin 60 mg/12 h). The patient's haemodynamic instability required haemodynamic support with vasoactive drugs for 15 days with maximum norepinephrine doses of up to 1 μg/kg/min.

The first blood gas analysis after connection to mechanical ventilation (MV) showed a P:F (PaO2/FiO2) ratio of 60, so prolonged prone positioning was performed, achieving a PaFi of 134. Given the improvement in oxygenation, it was decided not to perform any more prone-supine positioning cycles, with P:F ratio of 260 during the first week in supine.

While admitted, the patient required progressively decreasing haemodynamic support. A percutaneous tracheostomy was performed 10 days after intubation, and the sedatives/analgesics was progressively withdrawn. The patient presented abundant episodes of space and time disorientation, and fluctuation in her level of consciousness, with GCS between 12−14. This led to prolonged ventilator weaning along with poor management of secretions. After 23 days of MV, decannulation was well tolerated.

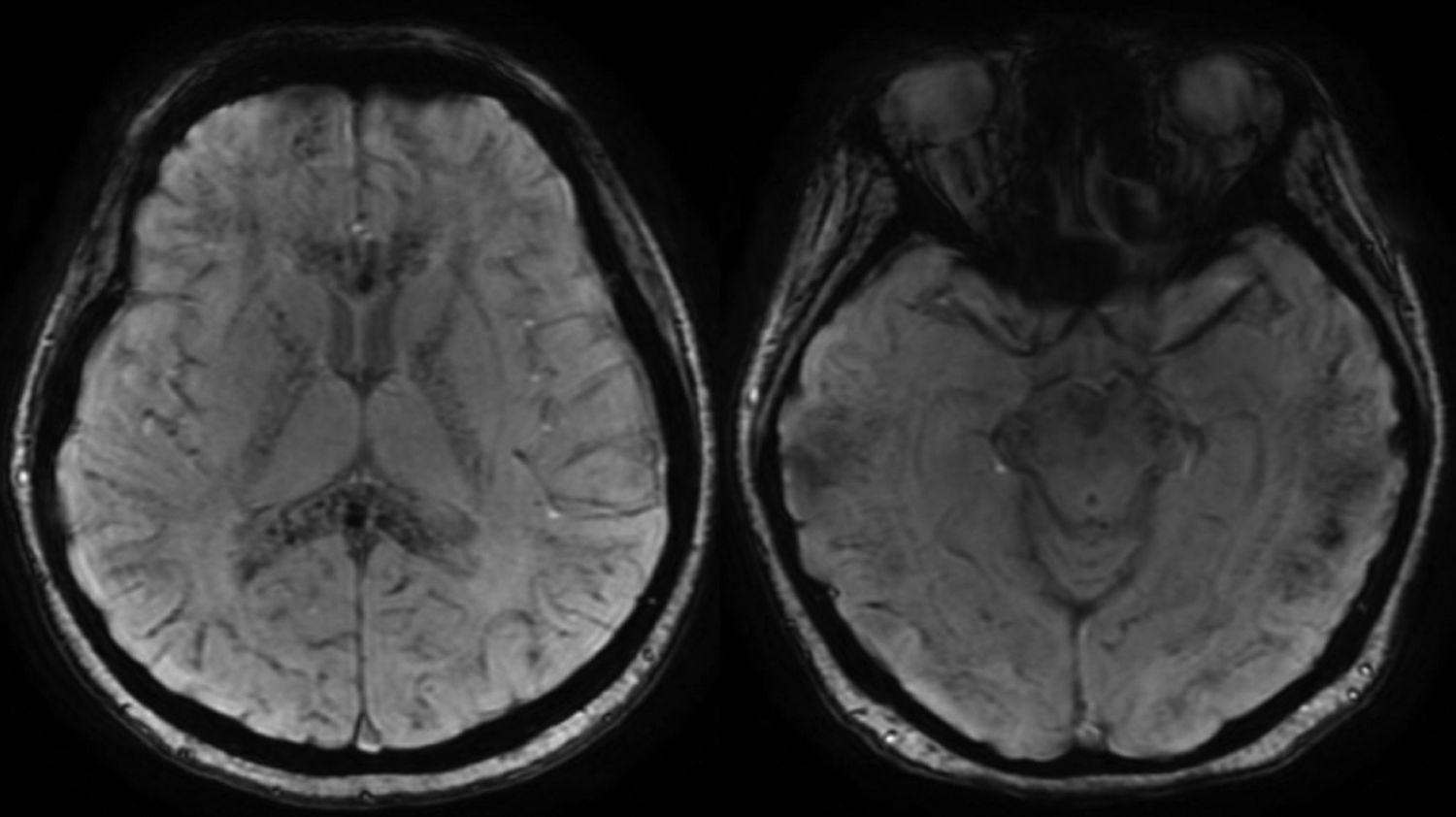

The patient made good progress and was moved to a conventional ward. While on the ward, she continued to have a tendency to sleep and episodes of agitation, which at first was attributed to probable confusional syndrome. Due to the persistence of the episodes, an MRI (Fig. 1) was performed. Multiple focal lesions were observed, located at the junction of the grey-white matter in the corpus callosum, plus anterior white commissure and internal capsules. These findings suggested diffuse axonal injury. Given the absence of trauma, other etiologies were evaluated, bearing in mind the published cases of severe patients in a situation of respiratory distress.1

Brain MRI in magnetic susceptibility sequences. Multiple microbleeds can be seen that affect both the supra- and infra-tentorial compartments, located more superficially at the cortical-subcortical junction and deep, with more significant involvement, of the corpus callosum, internal capsules, and anterior white commissure. These findings suggest diffuse axonal injury.

The patient's respiratory condition progressively improved, while a marked decrease in processing speed with impaired attention and executive functions persisted. She was allowed home after 10 days in the internal medicine ward, with a scheduled visit for follow-up by neurology, in the cognitive impairment consultancy.

The definitive diagnosis of diffuse axonal injury is established by autopsy; however, there are MRI findings suggestive of this entity, such as microbleeds in the cortical-subcortical part of the convexity, in the posterior part of the corpus callosum, and the lateral part of the mid brain.

After reviewing the patient's history, and given that aside from traumatic brain injury, hypoxia is a possible aetiology of diffuse axonal injury, we are able to conclude that the data found in our patient support the diagnosis of diffuse axonal injury in the context of hypoxaemia and acute respiratory distress due to infection by SARS-CoV-2. So far, cases of intraparenchymal haemorrhage have been reported in patients with no comorbidity other than COVID-19 infection,4 as have brain lesions with ring contrast enhancement,5 but to our knowledge, no cases have yet been described that demonstrate a correlation between COVID-19 and diffuse axonal injury.

Please cite this article as: Lopez-Fernández A, Quintana-Diaz M, Sánchez-Sánchez M. Lesión axonal difusa asociada a infección por COVID-19. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;155:274–275.