To assess clinical outcomes according to the immunosuppressive treatment administered to patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and moderate inflammation.

MethodsA retrospective observational cohort study involving 142 patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia and moderate inflammation divided into three treatment groups (pulses of methylprednisolone alone [group I], tocilizumab alone [group II] and methylprednisolone plus tocilizumab [group III]). The aim was to assess intergroups differences in the clinical course with a 60-day follow-up and related analytical factors.

Results14 patients (9,8%) died: 8 (10%) in group I and 6 (9,5%) in groups II and III. 15 (10,6%) were admitted to ICU: 2 (2,5%) from group I, 4 (28,5%) from group II and 9 (18,4%) from group III. The mean hospital stay was longer in group II and clinical outcome was not associated with treatment.

ConclusionsTocilizumab seems to be not associated with better clinical outcomes and should be reserved for clinical trial scenario, since its widespread use may result in higher rate of ICU admission and longer mean hospital stay without differences in mortality rate and potentially adverse events.

Analizar si existen diferencias en desenlaces clínicos según el tratamiento inmunosupresor recibido en pacientes con neumonía grave por SARS-CoV-2 e inflamación moderada.

MétodosEstudio de cohortes retrospectivo de 142 pacientes con neumonía grave COVID-19 e inflamación moderada. Se dividieron en tres grupos de tratamiento (pulsos de metilprednisolona solo [grupo I], tocilizumab solo [grupo II] y metilprednisolona más tocilizumab [grupo III]). Analizamos las diferencias intergrupos en el curso clínico con un seguimiento de 60 días y factores clínicos analíticos relacionados.

ResultadosFallecieron 14 pacientes (9,8%): 8 (10%) del grupo I y 6 (9,5%) de los grupos II y III. Quince (10,6%) ingresaron en UCI: 2 (2,5%) del grupo I, 4 (28,5%) del grupo II y 9 (18,4%) del grupo III. La estancia media hospitalaria fue mayor en los del grupo II. La evolución clínica no se asoció al tratamiento administrado.

ConclusionesEl uso de tocilizumab debería reservarse para escenarios de ensayos clínicos. Su utilización generalizada podría acompañarse de mayor estancia media hospitalaria e ingreso en UCI sin diferencias en la mortalidad con un potencial aumento de efectos adversos.

A severe respiratory syndrome associated with a new human coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 was identified in December 2019, rapidly becoming a global public health concern. This syndrome comprises several clinical phases, one of them hyperinflammatory, which usually occurs between day 6°–13° after the onset of infection. There is a direct correlation between this hyperinflammation, the severity of pneumonia, and the progression to respiratory failure and death.1 Various treatments have been used in this phase, although glucocorticoids alone have been shown to reduce mean hospital stay, ICU admission, and mortality.2,3 Observational studies suggest that other drugs such as tocilizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against the IL-6 receptor, reduce mortality and the need for mechanical ventilation.4,5 However, clinical trials in this regard have not confirmed a lower mortality6–8 with the use of tocilizumab. Very few patients were on glucocorticoids in these trials, and they were not designed to assess whether tocilizumab plus glucocorticoids might have additional clinical benefit. Glucocorticoids and tocilizumab have been widely used in our country, so we decided to study differences in the clinical course with a follow-up of 60 days between patients admitted to our hospital with severe pneumonia associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection treated with glucocorticoids alone versus those who received tocilizumab alone or with glucocorticoids.

Material and methodsRetrospective cohort study carried out at the San Cecilio Hospital in Granada. Patients admitted consecutively between 15th March and 15th May 2020 with severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia confirmed by nasopharyngeal swab PCR, fever >38 °C for at least 5 days and who met the criteria for moderate inflammation defined by two of the following conditions: PCR > 100 mg/l, ferritin > 500, D dimer > 1 mg/l with a procalcitonin < 0.05. Severe pneumonia was considered if there was also a baseline O2 saturation < 93% or a O2 partial pressure < 65 mmHg with radiological evidence of single or multilobar involvement compatible with COVID-19.

Patients received standard treatment according to our Hospital protocol at the time, unless contraindicated, consisting of hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, and lopinavir/ritonavir, together with thromboembolic disease prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin.

We classified the patients into three groups based on the immunosuppressive treatment administered: group I, glucocorticoids alone (methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg/day intravenous for 3 days with the possibility of another 2 days if clinical improvement was partial); group II, tocilizumab alone (single intravenous dose of 400 mg if weight <75 kg or 600 mg if weight >75 kg); group III, glucocorticoids and tocilizumab.

Comorbidities were collected, the PROFUND, CURB65 and qSOFA indices were calculated. The laboratory data analysed were: ferritin, CRP, lymphocytes with CD4/CD8 subpopulations, D dimer and procalcitonin. In addition, the extent of pneumonia was analysed based on chest X-ray or CT scans.

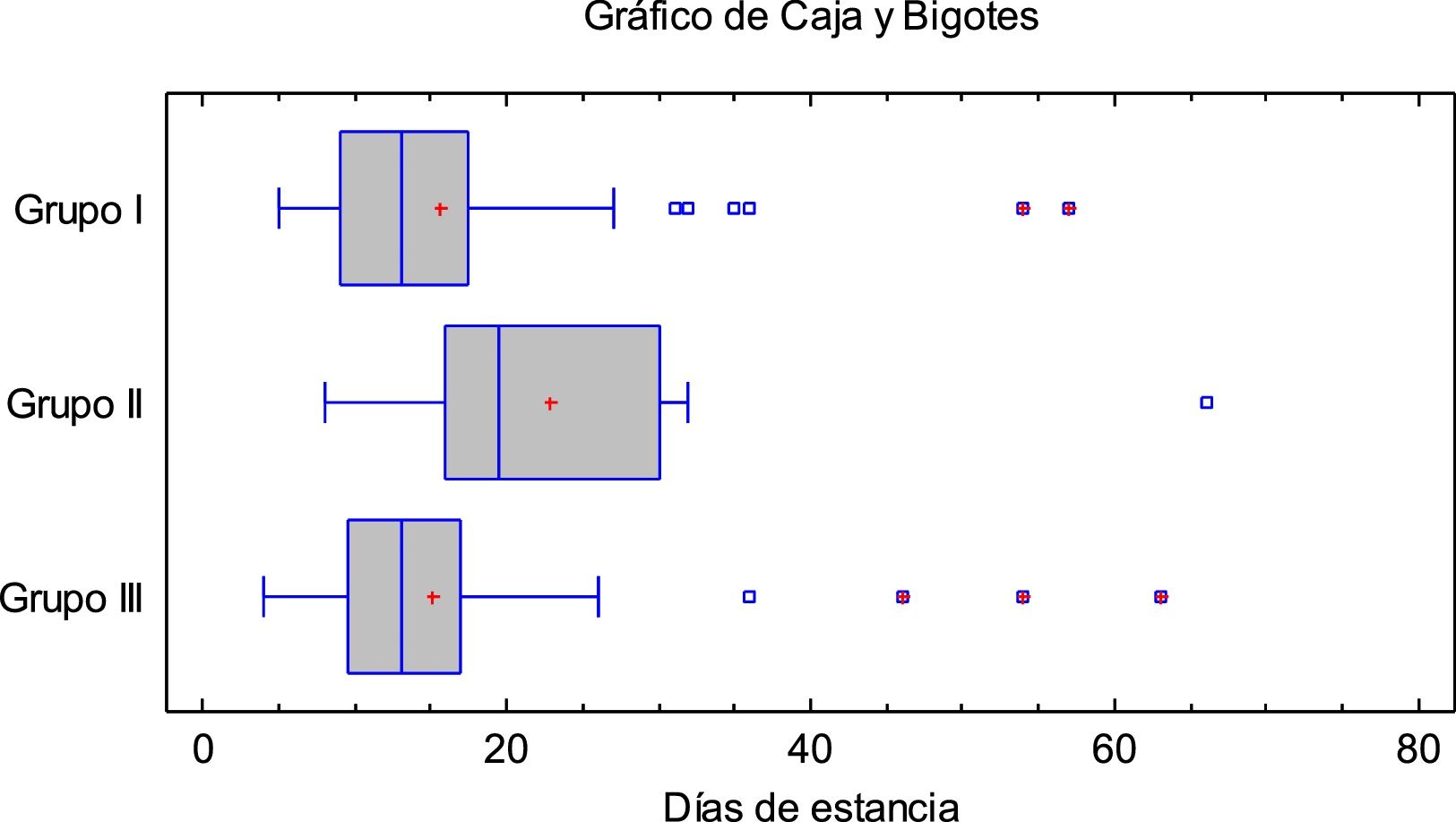

StatGraphics Centurion Version XVII and SPSS Version 23 were used for statistical analysis. After a descriptive analysis, the Chi-squared test of independence was performed to study the association between the treatments and the factors considered. The comparison of means of the analytical data according to treatment was carried out using an analysis of variance for independent samples (ANOVA). Descriptive subgroup analyses, bar charts, and box-and-whisker plots were also used to compare means and percentages.

The study was carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Each patient, their legal representative or closest family member was informed about the use of these treatments off-label, obtaining an informed consent for their administration.

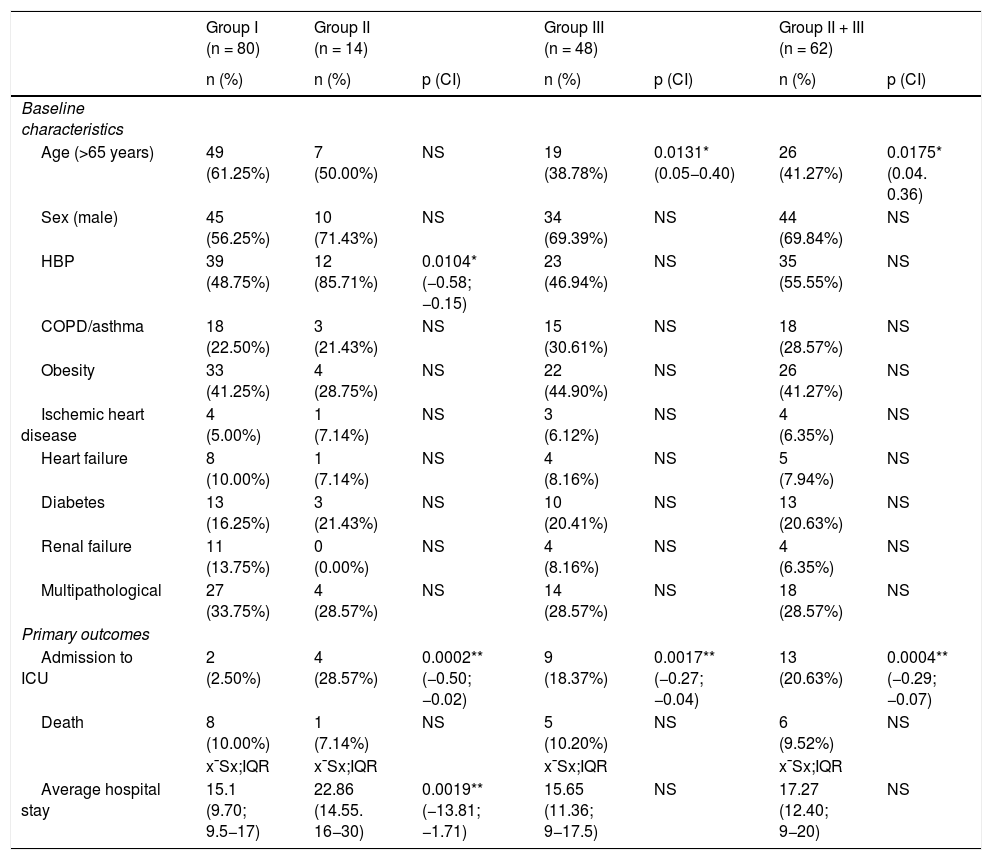

ResultsA total of 142 consecutively admitted patients were included. The baseline characteristics, comorbidities and administered treatments are shown in Table 1. Of the 142 patients, 80 (56.4%) received glucocorticoids alone, 14 (9.8%) tocilizumab alone, and 48 (33.8%) glucocorticoids and tocilizumab.

Baseline characteristics, comorbidities, and progression according to treatment.

| Group I (n = 80) | Group II (n = 14) | Group III (n = 48) | Group II + III (n = 62) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | p (CI) | n (%) | p (CI) | n (%) | p (CI) | |

| Baseline characteristics | |||||||

| Age (>65 years) | 49 (61.25%) | 7 (50.00%) | NS | 19 (38.78%) | 0.0131* (0.05−0.40) | 26 (41.27%) | 0.0175* (0.04. 0.36) |

| Sex (male) | 45 (56.25%) | 10 (71.43%) | NS | 34 (69.39%) | NS | 44 (69.84%) | NS |

| HBP | 39 (48.75%) | 12 (85.71%) | 0.0104* (−0.58; −0.15) | 23 (46.94%) | NS | 35 (55.55%) | NS |

| COPD/asthma | 18 (22.50%) | 3 (21.43%) | NS | 15 (30.61%) | NS | 18 (28.57%) | NS |

| Obesity | 33 (41.25%) | 4 (28.75%) | NS | 22 (44.90%) | NS | 26 (41.27%) | NS |

| Ischemic heart disease | 4 (5.00%) | 1 (7.14%) | NS | 3 (6.12%) | NS | 4 (6.35%) | NS |

| Heart failure | 8 (10.00%) | 1 (7.14%) | NS | 4 (8.16%) | NS | 5 (7.94%) | NS |

| Diabetes | 13 (16.25%) | 3 (21.43%) | NS | 10 (20.41%) | NS | 13 (20.63%) | NS |

| Renal failure | 11 (13.75%) | 0 (0.00%) | NS | 4 (8.16%) | NS | 4 (6.35%) | NS |

| Multipathological | 27 (33.75%) | 4 (28.57%) | NS | 14 (28.57%) | NS | 18 (28.57%) | NS |

| Primary outcomes | |||||||

| Admission to ICU | 2 (2.50%) | 4 (28.57%) | 0.0002** (−0.50; −0.02) | 9 (18.37%) | 0.0017** (−0.27; −0.04) | 13 (20.63%) | 0.0004** (−0.29; −0.07) |

| Death | 8 (10.00%) | 1 (7.14%) | NS | 5 (10.20%) | NS | 6 (9.52%) | NS |

| x¯Sx;IQR | x¯Sx;IQR | x¯Sx;IQR | x¯Sx;IQR | ||||

| Average hospital stay | 15.1 (9.70; 9.5−17) | 22.86 (14.55. 16−30) | 0.0019** (−13.81; −1.71) | 15.65 (11.36; 9−17.5) | NS | 17.27 (12.40; 9−20) | NS |

NS: non-significant.

Confidence intervals are indicated for significant comparisons regarding difference of proportions or difference of means as appropriate.

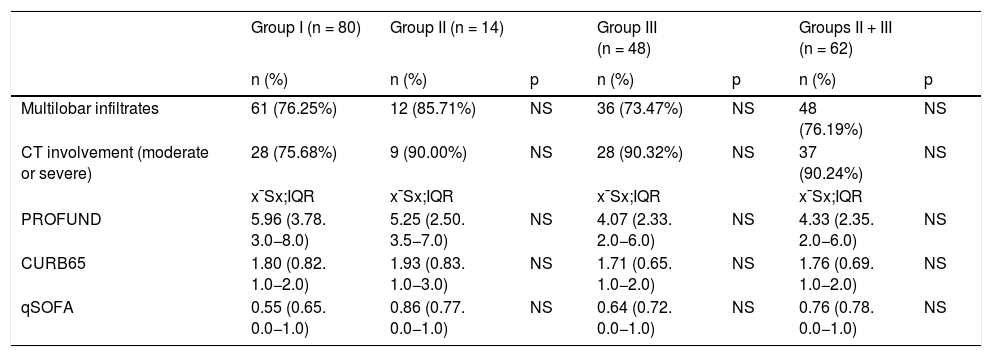

There were no differences in the percentage of comorbidities between the different treatment groups, except for a higher percentage of hypertensive patients in group II versus group I and a lower percentage of those over 65 years of age in group III versus group I. There were no differences at the time of admission with respect to the PROFUND, CURB 65, qSOFA indices or degree of radiological involvement (Table 2). Forty-nine (34%) patients were multipathological with a mean PROFUND index of 5.31; 109 patients (76%) had multilobar infiltrate on radiography and 65 (46%) had moderate/severe involvement on chest CT.

Clinical scales, involvement by chest X-ray and/or chest CT scan according to treatment groups.

| Group I (n = 80) | Group II (n = 14) | Group III (n = 48) | Groups II + III (n = 62) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | |

| Multilobar infiltrates | 61 (76.25%) | 12 (85.71%) | NS | 36 (73.47%) | NS | 48 (76.19%) | NS |

| CT involvement (moderate or severe) | 28 (75.68%) | 9 (90.00%) | NS | 28 (90.32%) | NS | 37 (90.24%) | NS |

| x¯Sx;IQR | x¯Sx;IQR | x¯Sx;IQR | x¯Sx;IQR | ||||

| PROFUND | 5.96 (3.78. 3.0−8.0) | 5.25 (2.50. 3.5−7.0) | NS | 4.07 (2.33. 2.0−6.0) | NS | 4.33 (2.35. 2.0−6.0) | NS |

| CURB65 | 1.80 (0.82. 1.0−2.0) | 1.93 (0.83. 1.0−3.0) | NS | 1.71 (0.65. 1.0−2.0) | NS | 1.76 (0.69. 1.0−2.0) | NS |

| qSOFA | 0.55 (0.65. 0.0−1.0) | 0.86 (0.77. 0.0−1.0) | NS | 0.64 (0.72. 0.0−1.0) | NS | 0.76 (0.78. 0.0−1.0) | NS |

CURB65: mortality prediction scale used in patients with community-acquired pneumonia; NS: non-significant; PROFUND: prognostic scale for multipathological patients in the hospital and primary care population; qSOFA: quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

On admission, patients in group I had lower CRP and IL6 values and lower ferritin levels at 3 days and at 1 month.

Fig. 1 shows the mean hospital stay according to the treatment received. Regarding disease progression at two months: 14 (9.8%) had died: 8 (10%) of group I and 6 (9.5%) in the groups that received tocilizumab; 15 (10.6%) required admission to the ICU: 2 (2.5%) of group I, 4 (28.5%) of group II (p = 0.0002 vs group I, 9 (18.4%) of group III (p = 0.0017 vs group I. Of these, 12 (80%) required orotracheal intubation: 2 (16.67%) of group I, 3 (25%) of group II and 7 (58.3%) of group III.

There was no difference in mean hospital stay between patients in groups I and III, with longer stays in group II (15.1 vs 22.86 vs 15.65 days for groups I, II and III; p = 0,0019). In addition, based on the Chi-square test, progression at 2 months did not depend on the treatment administered.

DiscussionImmunosuppressive therapies are used in patients with severe SARS CoV-2 pneumonia and moderate inflammation due to the pathogenic role of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Glucocorticoids have been shown to reduce mortality and ICU admission.2,3 Tocilizumab has been widely used based on observational studies that suggest a reduction in the risk of intubation and/or death,4,5 although clinical trials6–8 have not shown a lower mortality at 28 days. Given the discrepancies in the scientific evidence, we decided to analyse the clinical progression at 60 days in our cohort of patients according to the immunosuppressive treatment received.

We did not find significant differences in mortality or mean stay between the different treatment groups. A smaller number of patients in group I (2.5%) was admitted to the ICU compared to those who received tocilizumab alone (28.5%) or glucocorticoids and tocilizumab (18.4%). This could be due to selection bias, since in those early months of the pandemic, due to ICU overcrowding, patients with shorter life expectancy probably received glucocorticoids alone and were discarded from intensive care. However, although patients receiving glucocorticoids alone had fewer ICU admissions, 60 day mortality between the different groups was similar, which is consistent with the conclusions of the main clinical trials of tocilizumab.6–8

In our study, the use of tocilizumab with or without glucocorticoids was not accompanied by a clinical benefit in terms of mortality, ICU admission, or mean hospital stay. Rodríguez-Baño et al.9 found that there is a higher percentage of patients who require intubation or die (follow-up of 21 days) in those who received glucocorticoids and tocilizumab compared to the “no treatment” group (26.5% vs 20.1%).

Other observational studies10 have suggested a benefit of glucocorticoids after tocilizumab with lower mortality (20% vs 62%). We did not observe differences with the concomitant use of glucocorticoids and tocilizumab, although we did not include any group that had received tocilizumab prior to glucocorticoids.

Our data seem to suggest that the use of tocilizumab in these patients does not provide a benefit in terms of mortality, ICU admission, or mean hospital stay. We believe that until more conclusive evidence emerges, and tocilizumab-responsive patient profiles are identified, it may be prudent to limit its use in this clinical setting.

FundingThis research has not received any type of funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Our thanks go to all the healthcare workers who are fighting on the frontline of this pandemic on a daily basis and to Dr Luis Aliaga Martínez for his valuable advice in the writing of this paper.

Acknowledgement of the project P18-RT-1765. BIGDATAMED. Data analysis in medicine: from medical records to Big Data. RDI project of the Junta de Andalucía, Spain.

Both authors have contributed equally to the manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Aomar-Millán IF, Salvatierra J, Torres-Parejo Ú, Nuñez-Nuñez M, Hernández-Quero J, Anguita-Santos F. Glucocorticoides solos versus tocilizumab solo o glucocorticoides más tocilizumab en pacientes con neumonía grave por SARS-CoV-2 e inflamación moderada. Med Clin (Barc). 2021;156:602–605.