The demands of transgender people have been part of the ongoing social and political debate in the European context for the last decade. In response, in 2015, the Council of Europe called for “the development of quick, transparent and accessible procedures, based on self-determination, to change both the name and gender on their birth certificates, identity cards […] and similar documents”.1 Between 2014 and 2019, Denmark, Ireland, Malta, Belgium and Luxembourg, as well as Norway and Iceland, outside the European Union, passed laws to transpose such guidelines in this area. These countries have recently been joined by Spain, whose legislative changes in relation to gender self-determination are reflected in the healthcare context.2 Law 4/2023, for the real and effective equality of trans people and for the guarantee of the rights of lesbian, gay, transsexual, bisexual and intersex (LGTBI) people, modifies the possible clinical interventions with the aim of eliminating situations of discrimination and guaranteeing the freedoms of this group. In this sense, it establishes the need for measures that provide comprehensive health care for trans people under the principles of non-pathologisation, autonomy, informed decision and consent, non-discrimination, quality, specialisation, proximity and non-segregation (art. 56).

Although the existence of people whose gender identity and expression differ from the Western categories of ‘male’ and ‘female’ is not a new phenomenon, society in general and the medical community in particular have recognised the increase in the number of visible transgender people in recent years.3–5 A recent study conducted in 30 countries around the world found that 1% of people identify themselves as transgender; 1% as non-binary, gender non-conforming or gender fluid; and 1% as none of the above, but neither male nor female. In Spain, 4% of the population identifies with any of the above groups, making it one of the countries with the largest transgender population in the study.6

The process of gender transition is complex and lies on a continuum that is neither strict nor necessarily linear. It varies from person to person and can include social, hormonal and/or surgical components in what is known as the transition spectrum.7 Some people opt for medical interventions to bring their physical appearance in line with their gender identity, while others only wish to assume the gender role that corresponds with their identity.8 Therefore, the existing literature underscores the importance of considering the unique aspects of each trans person through respectful assessment in order to provide competent care for this population.9,10

In addition to their population size, transgender people have specific medical problems and characteristics that make them more vulnerable. Their rates of mental health problems, suicide attempts, substance abuse, sexually transmitted infections, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis and cancer are higher compared to their cisgender (non-transgender) peers.9,11,12 The mortality rate is also significantly higher compared to the general population, especially due to cardiovascular diseases, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and suicidal acts. However, specific prevalence figures and impact by country are unknown, and studies are needed to address these gaps in knowledge.7,9,13–15 This lack of scientific evidence extends to the long-term safety of hormone transition (HT),12,14,15 which also contributes substantially to health disparities in this population.3,7,11,12

In this context, Primary Care (PC), as the first point of contact with health maintenance and care,16 can contribute to reducing inequities affecting transgender people, often linked to stigma and discrimination.9 The reasons why transgender individuals come to PC may or may not be related to transition. Regardless of the reason for the consultation, they want or expect their caregivers to be aware of the specificities of transgender care, an expectation that is not always met.17

The aim of this article is to explore the barriers to care faced by the transgender adult population in accessing and receiving quality PC, as well as to identify specific actions that can facilitate a response to their needs.

The problem of terminologyThe lack of agreement on the definition of trans and related concepts such as sex, gender or gender identity is part of a complex debate that goes beyond the scope of this paper but has direct consequences for the treatment of trans people. Without a standardised nomenclature, epidemiological characterisation is difficult. This situation affects the recognition and approach to the needs, expectations and health disparities experienced by this group.18 Therefore, in order to understand the reality of this group, it is necessary to clarify the conceptual starting point.

In accordance with the objective of this paper, we understand sex as the biological characteristics attributed to men and women, while gender refers to the socially constructed roles assigned to men and women, which can vary from one society to another and over time.19 Due to genetic or developmental variations, some people do not obey these typified categories, such as intersex and non-binary people. Although they may be interrelated, gender identity and sexual orientation are also two separate entities. Gender identity is one's internal sense of one's own gender, while sexual orientation refers to one's attraction to persons of either sex.9,20 While the concept of “transsexuality” came to be included under mental disorders in the World Health Organisation's (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 (1990), the term that replaces it - transgender - is no longer presented as a pathological condition, but as a reality that includes people living in accordance with their gender identity, either with or without medical (hormonal and/or surgical) transition.5,11

The latest version of the ICD (ICD-11/2022) included gender incongruence within the section on sexual health situations in order to ensure its health coverage.21 Gender incongruence is defined there as “a marked and persistent incongruence between an individual's experienced gender and assigned sex, often leading to a desire to 'transition' in order to live and be accepted as a person of the experienced gender through hormonal treatment, surgery or other health care services”.22 This places transgender people outside the context of mental illness, although it is still considered as a situation that may be accompanied by distress and specific health needs. Thus, in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5/2013), gender dysphoria is the “distress that may accompany incongruence between experienced or expressed gender and gender assigned at birth”.23 This approach focuses on dysphoria as a treatable clinical problem, not on identity per se.

ICD-11 and DSM-5 reflect efforts to remove the disease category from trans status, updating the terms used to understand, accompany and ensure care for the conditions of discomfort that may be associated with trans status. Despite this, there are critical voices that claim the need to eliminate the concepts of “gender discordance and incongruence” and “gender dysphoria” from ICD-11 and DSM-5, respectively. From this perspective, these concepts contribute to the desire for medical transition being seen as a clinical indication requiring a psychiatric diagnosis, thus maintaining a disease-like approach to transgender status.24 Furthermore, both nosologies continue to include these diagnoses within a framework that is far removed from the social determinants of health, focusing the discomfort on the person themselves rather than the transphobia coming from society. The qualification of illness that has traditionally been raised in these classifications, and which has been taught in medical schools, has contributed greatly to the consideration of trans identities as pathologies within the medical community.25

Today, the term trans is also used to refer to the spectrum of people with gender variants beyond male or female. It includes not only trans men (a person with male gender identity and female gender assigned at birth) and trans women (a person with female gender identity and male gender assigned at birth); it also incorporates those whose gender expression is non-binary.4 Finally, cisgender persons are those whose gender identity and/or gender expression coincides with the sex they were assigned at birth.4

Barriers to healthcare accessTransgender people are a highly stigmatised and marginalised population,6 facing barriers that prevent them from equitable access to resources essential to the development of their vital dimensions, including health care.5 Their specific needs are largely unmet, exacerbating inequalities and poor health outcomes in this population.5,13,26,27

The main barriers to care faced by transgender people are the lack of training of medical staff on their specific needs,13,28 microaggressions and their negative experiences in healthcare settings.11,13,17 These difficulties are further aggravated by a lack of resources (care, organisation, training and research) and biases in the electronic health record (name, gender assigned at birth and gender identity), which make it difficult to understand and address the specific health needs of this population.5,11,13 Other barriers that have been documented are the lack of expertise7 and gaps in research with and on transgender people,4,5,27 especially in health promotion and disease prevention.13

All these factors mean that transgender people delay or even avoid medical care.11,13,17 According to Garnier et al., 25% of transgender people delay their visit to the PC clinic and 17% have given up, regardless of the reason for their visit.17

The social determinants of health also contribute to the inequalities experienced by this population.11 They are more exposed to violence, with higher rates of both unemployment (due to the additional stigmatised difficulties they face in finding work) and homelessness. These are factors related to poorer health and health care, in addition to so-called minority stress.3,11 The latter results from the discrimination and stigma faced by transgender people. It leads to an increased vulnerability to develop mental health problems such as anxiety and depression.3 Particularly in contexts where hate speech and aggression towards this group occurs.25

The health of this population can be improved by changing the mechanisms that induce stigma and discrimination, removing barriers to accessing health services and improving their care.

Suggestions for improving health care for transgender people in primary careIn order to reduce barriers and improve health outcomes, actions have been documented that favour both access to and use of health resources and the provision of competent and quality care for transgender people. Some of them, due to their structural nature, belong to the field of health policy and management, and therefore depend on institutional bodies. Other measures have a direct application in the care context and are linked to professional work. Although the two levels interact, they are presented separately for the sake of clarity.

Proposals for improvement from the institutionsDue to its accessibility, the involvement of PC medicine is essential to provide a comprehensive response and promote access and continuity of care for the transgender population.3,5,12 However, a training deficit has been detected at this level of care, which is worrying in terms of the possibility of decentralising care for this group.5,26 To overcome this deficit, there is a need to strengthen interdisciplinary cooperation3,10,26 and to involve health professionals, as well as to implement strategies for training in trans skills, knowledge and cultural competence.3,5,11–13,26,28 This is not only for working professionals, but also for university students.5,11

Cultural competence is defined as the ability to care for transgender people according to their needs.13 It encompasses aspects such as the use of respectful language3,7; the standardisation in the electronic register of terms related to gender identity3,13,28; the collection of medical records sensitive to the reality of the individual15 and the creation of sensitive and inclusive environments for trans people.7,10,15 This is intended to avoid actions lacking scientific evidence based on ideological positions.15 In this sense, increased resources and research will help to provide better care.9,11,12,26

The demand for self-determination of gender identity is a controversial aspect that is inconsistently reported by trans people.26 On the one hand, some see self-determination as overriding scientific reasoning and subjecting the medical profession to individual desire.12 From this point of view, self-determination is seen as implying a demand by non-experts to initiate medical actions that involve risks to the health of the individual.26 On the other hand, self-determination is advocated as a means to stop classifying the trans condition as an illness and to respect the individual's ability to make decisions regarding his or her health.26 There are intermediate positions that consider that the biomedical perspective is not at odds with respect for personal autonomy. According to this approach, shared decision making plays a central role in caring for transgender people.3,7,26 Given the lack of consensus in the health sector, in the case of Spain, it will be necessary to pay attention to the implementation of the measures established in Law 4/2023 in relation to gender self-determination and to identify the possible risks, harms, benefits and shortcomings of this new regulatory framework.

Proposals for improvement in primary care clinicsAs the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) reveals, there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to care for transgender people.3 Not all transgender people wish to modify their bodies through hormones or surgery,9 so medical consultations should focus on the specific health needs of the individual.3 Nevertheless, this organisation proposes the most common model of care, the Standards of Care in its eighth version (SOC-8).3 Among its criteria for the medical treatment of the adult trans population, it recognises gender identity as an experience of internal identification, assigning the following responsibilities to health professionals: 1) confirm the presence of gender incongruence; 2) identify the coexistence of mental health problems; 3) offer information about possible medical treatment; 4) support the trans person in reflecting on the effects and risks of transition therapy; and 5) establish whether they have the capacity to understand the treatment they are offered and whether such treatment may be beneficial. This approach acknowledges the experience and self-knowledge of the transgender person, but also the experience of the health professional, with the aim of shared decision-making about the most appropriate treatment.3

The SOC-8 approach is based on criteria that have a pathological and patronising connotation for transgender people, such as the use of the concept of ‘gender incongruence’ and the specific recommendation to identify the co-occurrence of mental health problems or the person's ability to understand the treatment being offered. These considerations introduce differential elements in relation to other clinical procedures the need for which would require a justification that is not provided in the SOC-8.

Alongside this approach, other forms of care are being promoted to reduce barriers and improve health outcomes,3,5 which can be implemented in PC settings. These include models such as patient-centred care,3,29 the integrated approach,3 the informed consent model,28 or the harm reduction approach.3 The patient-centred care model redefines the traditional paternalistic approach by emphasising the autonomy and self-determination of the individual, who takes the lead in collaboration and shared decision-making with professionals. On the other hand, the integral approach is based on biopsychosocial care based on listening to the needs, desires and expressed gender identity; it is the individual who decides the path he/she wants to follow and what services he/she needs. In line with previous approaches, the informed consent model assumes access to medical interventions (including HT) without a mental health assessment and without a diagnosis of dysphoria, so that it is gender self-determination that governs the care relationship. Finally, the harm reduction approach includes public health strategies that aim to ensure longer life expectancy and better health for transgender people in the context of stigma, violence and discrimination against them. These include not only good accessibility to health care, with professionals able to provide competent trans care, but also other social aspects such as access to housing and employment, the creation of gender-affirming safe spaces, etc.

Although there are differences between them, and these are beyond the scope of this paper, these models provide general guidelines for the provision of quality transgender PC: person-centred care, informed decision-making and a sensitive approach based on reducing the physical, emotional and social harm to which transgender people are particularly vulnerable due to discrimination and violence.

Beyond the care model chosen, there are a number of considerations to be taken into account in the medical encounter with a transgender person. Firstly, it is advisable to establish a care relationship based on trust.7,9,10 This can be helped by familiarising oneself with the terminology related to the trans reality, as it is a sign of knowledge, interest and respect.3,5,7,28 Given the terminological difficulties mentioned above, we suggest agreeing with the person how they prefer to be addressed or the same goes for their body parts.5,15 This type of intervention can promote continuity of care and good participation in self-care.3

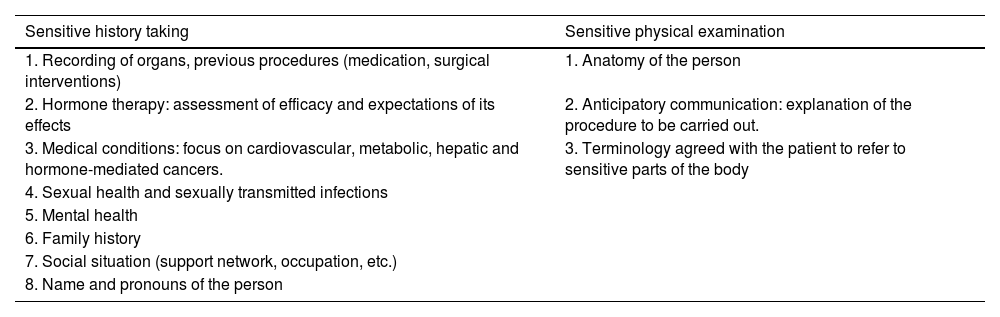

Secondly, it is essential that a sensitive history taking and, if necessary, a sensitive physical examination is carried out in accordance with the specific considerations that need to be taken into account when caring for a transgender person.3,10,11,17 These considerations are set out in Table 1.

Specific considerations for a medical encounter with a transgender person.

| Sensitive history taking | Sensitive physical examination |

|---|---|

| 1. Recording of organs, previous procedures (medication, surgical interventions) | 1. Anatomy of the person |

| 2. Hormone therapy: assessment of efficacy and expectations of its effects | 2. Anticipatory communication: explanation of the procedure to be carried out. |

| 3. Medical conditions: focus on cardiovascular, metabolic, hepatic and hormone-mediated cancers. | 3. Terminology agreed with the patient to refer to sensitive parts of the body |

| 4. Sexual health and sexually transmitted infections | |

| 5. Mental health | |

| 6. Family history | |

| 7. Social situation (support network, occupation, etc.) | |

| 8. Name and pronouns of the person |

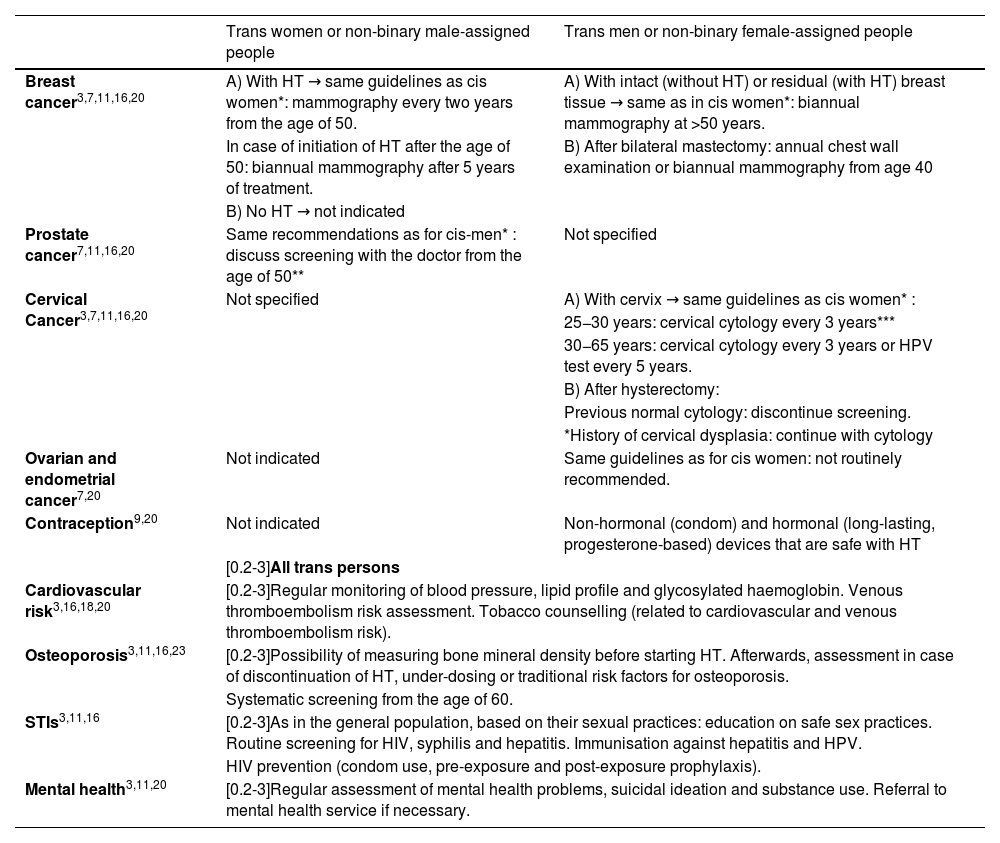

Despite their importance, medical interventions are insufficient to reduce health disparities in this population,11,12 as their needs go beyond gender identity or transition.9,28 For this reason, awareness and implementation of health promotion and screening practices for the most prevalent diseases in transgender people are urged.3,14 The main recommendations are listed in Table 2 and are based on the individual's current anatomy, as well as on HT or surgical procedures.3,9,15

Recommendations for preventive care for transgender people.

| Trans women or non-binary male-assigned people | Trans men or non-binary female-assigned people | |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer3,7,11,16,20 | A) With HT → same guidelines as cis women*: mammography every two years from the age of 50. | A) With intact (without HT) or residual (with HT) breast tissue → same as in cis women*: biannual mammography at >50 years. |

| In case of initiation of HT after the age of 50: biannual mammography after 5 years of treatment. | B) After bilateral mastectomy: annual chest wall examination or biannual mammography from age 40 | |

| B) No HT → not indicated | ||

| Prostate cancer7,11,16,20 | Same recommendations as for cis-men* : discuss screening with the doctor from the age of 50** | Not specified |

| Cervical Cancer3,7,11,16,20 | Not specified | A) With cervix → same guidelines as cis women* : |

| 25−30 years: cervical cytology every 3 years*** | ||

| 30−65 years: cervical cytology every 3 years or HPV test every 5 years. | ||

| B) After hysterectomy: | ||

| Previous normal cytology: discontinue screening. | ||

| *History of cervical dysplasia: continue with cytology | ||

| Ovarian and endometrial cancer7,20 | Not indicated | Same guidelines as for cis women: not routinely recommended. |

| Contraception9,20 | Not indicated | Non-hormonal (condom) and hormonal (long-lasting, progesterone-based) devices that are safe with HT |

| [0.2-3]All trans persons | ||

| Cardiovascular risk3,16,18,20 | [0.2-3]Regular monitoring of blood pressure, lipid profile and glycosylated haemoglobin. Venous thromboembolism risk assessment. Tobacco counselling (related to cardiovascular and venous thromboembolism risk). | |

| Osteoporosis3,11,16,23 | [0.2-3]Possibility of measuring bone mineral density before starting HT. Afterwards, assessment in case of discontinuation of HT, under-dosing or traditional risk factors for osteoporosis. | |

| Systematic screening from the age of 60. | ||

| STIs3,11,16 | [0.2-3]As in the general population, based on their sexual practices: education on safe sex practices. Routine screening for HIV, syphilis and hepatitis. Immunisation against hepatitis and HPV. | |

| HIV prevention (condom use, pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis). | ||

| Mental health3,11,20 | [0.2-3]Regular assessment of mental health problems, suicidal ideation and substance use. Referral to mental health service if necessary. | |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HPV: human papillomavirus; HT: hormone transition; STIs: sexually transmitted infections.

Most cancer screening recommendations are based on the guidelines followed in the cis population, in the absence of further research for the trans population.7,9

In addition to the institutional strategies outlined above to enable access to training,3,5,11–13,26,28 there is also a need for professional involvement in the acquisition of knowledge and skills that can improve the care of this group. Clinical practice guidelines can be used by healthcare professionals and students as support material.27 Among them, the most widespread are the WPATH standard of care and the Endocrine Society guidelines.27 The University of California's UCSF Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People complement the two previous ones by being designed for application in PC settings.14

Finally, it is important to remember that the health care, health promotion and disease prevention interventions outlined in this paper, while important, do not address the social stigma and oppression experienced by transgender people.3,11 It is therefore essential to integrate the social determinants of health into the care of transgender people11 in order to provide a comprehensive response to their needs. In this sense, coordination with specialised services is recommended for consultations or referrals in case of need.3,26

Hormone transition in primary careBased on the above premises, it has been shown that PC medicine can initiate and monitor HT to guarantee continuity of care for transgender people.3,9,11 The latest edition of the WPATH standards of care does not include referral to mental health as a prerequisite for initiating HT and shifts to PC the responsibility of determining whether the person has the capacity to make an informed decision about the process, just like any other user.3,11 This aspect has generated controversy, insofar as it has been interpreted as omitting the influence of psychosocial factors on gender identity and requiring skills in psychopathology that may exceed the competencies of family and community medicine.4,11,26 From the point of view of transgender people, the need to undergo a mental health assessment prior to HT means that the medical community, hospital or PC, becomes the judge of their decisions, undermining their autonomy and therefore the possibility of self-determination.30

In any case, the irreversibility and temporality of the changes, potential risks, fertility implications and gaps in clinical knowledge on these issues should be discussed before initiating the transition, with informed consent including risks and benefits, as with other processes.3,9–11 Expectations regarding the desired effects and limitations of HT should also be discussed in order to provide individualised care.3,10Table 3 lists the main physical changes, adverse effects and contraindications for HT.

Physical changes, possible adverse effects and contraindications of hormone transition (HT) in adults.

| Physical changes9,23 | Possible adverse effects3,9,11,13,14,20,23 | Contraindications9,11 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feminising HT | |||

| - Oestrogens | - Redistribution of body fat | - Venous thromboembolism | Absolute: |

| - Decreased muscle mass | - High blood pressure, overweight, hypertriglyceridemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease | - History of venous thromboembolism | |

| - Breast growth | - Cerebrovascular disease, migraine headaches | - History of oestrogen-dependent or active cancer | |

| - Reduction of testicular hair and volume | - Liver dysfunction, cholelithiasis | - End-stage chronic liver disease | |

| No change in tone of voice is expected. | - Infertility, hyperprolactinaemia | Caution: | |

| NOTE: These changes start in 3−6 months. Stabilisation in 5 years | - Prolactinoma | ○ Arterial hypertension | |

| - Possible risk of breast cancer | ○ Diabetes mellitus 2 | ||

| - Decreased libido and fertility | |||

| - Anti-androgens | Change in male secondary sexual characteristics | Only in case of spironolactone: hypotension, bone loss, hyperkalaemia | |

| Masculinising HT | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| - Testosterone | - Increased muscle mass | - Erythrocythaemia/polycythaemia | Absolute: |

| - Decrease in fat mass | - Arterial hypertension | - Pregnancy | |

| - Male pattern hair growth | - Increased LDL and triglycerides | - Severe coronary dependent or active disease | |

| - Voice deepening | - Acne | - Polycythaemia with haematocrit ≥ 54%. | |

| - Increased libido | - Diabetes mellitus 2 | - Active hormone-sensitive cancer | |

| - Amenorrhoea | - Cardiovascular events | Caution: | |

| NOTE: These changes start in 3−6 months. Stabilisation in 5 years | - Transaminitis | ○ Obstructive sleep apnoea | |

| - Infertility | |||

| - Vaginal atrophy | |||

| - Sleep apnoea | |||

HT: hormone transition; LDL: Low-Density Lipoprotein.

On the other hand, people who receive HT sometimes need lifelong follow-up,10 which can be made available by PC, according to the published guidelines.11 Although there are differences between the guidelines, Table 4 shows the main aspects that should be monitored.

Main tools for monitoring hormonal transition (HT) from Primary Care.3,13,14,23

| Tool | Type/periods of monitoring |

|---|---|

| 1) Targeted history taking: | a) Assessment of medication adherence |

| (b) Reporting of possible adverse effects every 3 months for the first year of treatment and then once or twice a year thereafter8,15 | |

| 2) Targeted physical examination: | (a) Determination of signs of masculinisation/feminisation, regular weight and blood pressure monitoring |

| (3) Laboratory determinations: | General indication |

| - Regular assessment of lipid profile and glycated haemoglobin. | |

| Trans women: | |

| Estradiol and testosterone every 3 months; | |

| Periodic assessment of prolactin* | |

| If on spironolactone, monitor potassium and renal function. | |

| Trans men: | |

| Haemoglobin, haematocrit and total testosterone every 3 months |

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and the University of California (UCSF) Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People only recommend periodic prolactin screening if there are visual disturbances, galactorrhoea or new-onset headaches.

This article shows that the complexity of the approach to gender identity is particularly relevant in the context of health care. This is evidenced by the lack of consensus on the definition of terms, the possibility of gender reassignment and its medical monitoring, and the variety of barriers to health care and medical problems affecting the transgender community. The consequences of this framework are reflected in a population with specific health needs that go unmet, leading to inequalities in this area. Therefore, in parallel to the socio-political discussion, there is a need for respectful debates on trans health, based on sound and impartial science, open to reflection and sensitivity.

There are health inequalities among transgender people (mental health, sexually transmitted infections, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis or cancer) and the exact magnitude of these inequalities is unknown. There are also gaps in clinical knowledge related to their specific health needs, the effect of long-term medical interventions and disease prevention recommendations, among others. In addition, most studies have been conducted in North America, so there is insufficient data to know the specific caseload in other contexts. Therefore, there are still avenues open for research on the trans reality in our environment, the results of which will lead to appropriate care for this group.

The main barriers to transgender people's access to and use of PC are a lack of knowledge and training on transgender health among healthcare staff. Therefore, the training of medical staff and their involvement in improving care for this group is critical to improving care. PC favours access, continuity of care and a comprehensive approach to the needs of transgender people, not only in relation to transition when it occurs, but also in relation to preventive care and health promotion practices.

Ethical considerationsThis paper is a review. No patients are included. Informed consent is not required.

FundingThis work is co-funded by the R + D + I in Health call for projects of the Strategic Action in Health (AESI PI22CIII/00018).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We wish to thank Paule González Recio, for her valuable comments on the article.