In 1959, Milton I. Roemer and Max Shain already advanced the hypothesis that, in an insured population, “an available hospital bed is a bed that tends to be used”.1 Subsequently known as Roemer’s Law, this premise has been widely accepted for all existing healthcare systems, including Spain’s.

This phenomenon could be considered within the context of inappropriateness in health care, defined as the study and adoption of health practices in situations where their effectiveness has been demonstrated, and the suppression of those practices that pose more risks than benefits. Thus, several types of inappropriateness in health care can be distinguished depending on whether a practice that would have brought a positive net benefit is omitted (underuse), or whether an unwarranted procedure is carried out (overuse).2 More specifically, overuse of hospital care could be defined as any unwarranted admission or stay in hospital because the risk-benefit balance is unfavourable to the patient, because it does not meet the patient’s real needs, or because there are other more efficient care alternatives.2 However, for a proper approach to this concept, a distinction must be made between the following forms of presentation:

Overuse of inpatient days: unnecessary occupation of a hospital bed, either as a result of premature admission or unwarranted delayed discharge. Within the study of overuse of hospital use, the measurement of days of inappropriate hospital stays was the first field developed. It originated in the USA, in the 1960s, when lack of accessibility was the focus of the health care debate, leading to the creation of the Medicare and Medicaid programmes. Based on expert panels, the first studies analysing hospital overuse began to emerge, showing a lack of homogeneity in criteria and wide variability in results. It is estimated that 24%–58% of inpatient days are inappropriate.3 This value may vary depending on the centres, the care services and the methodology used for measurement. The main causes of inappropriate hospital stays include those related to waiting for diagnostic or therapeutic tests, underuse of outpatient clinical processes and alternatives, conservative patient management, or the lack of an alternative care network in the out-of-hospital setting.4 In recent years, the latter reason is likely to become increasingly important as the population ages. This could be reflected in the emergence of new methods specifically aimed at studying appropriateness in the social and health care setting and outpatient management of the chronic patient.5,6

Overuse of hospital admissions: whether planned or urgent, may occur: 1) as an admission for an already unnecessary hospitalisation; 2) as a premature admission for a later appropriate hospitalisation (in such a case, it would imply inappropriate days of hospital stay at the beginning of the clinical episode). Its frequency of occurrence varies. In Spain, a 1995 review estimated it at 9%–18% for tertiary hospitals, 17%–44% for internal medicine departments and 10%–25% for emergency departments.7 Its main causes are unnecessary admissions from emergency departments (episodes of hospitalisation that could have been managed on an outpatient basis) and premature admissions related to the surgical field (patients who are admitted early because of their clinical situation or the type of health care they require).8

Both types of inappropriate hospitalisation can generally have common consequences. In this respect, any healthcare procedure (including hospitalisation) is generally considered to have an intrinsic risk of a safety incident occurring during its execution4,9. Therefore, if the procedure had been unjustifiably indicated, then the incident could potentially be considered avoidable. In the case of inappropriate hospitalisation, the risk to the patient is likely to be higher if: 1) it is combined with the indication of other additional procedures (whether or not associated with the hospitalisation itself), and 2) if such procedures have a high degree of complexity (such as certain interventions of an invasive nature).4 This possible association has recently been addressed in a sample of a tertiary hospital in Spain, where it was estimated that the risk of a patient with an inappropriate admission subsequently presenting with an adverse event was more than three times higher than in those whose admission was considered necessary.10 Other studies have also identified safety incidents following unwarranted hospitalisations, including serious adverse events such as a transfusion error or an episode of hypoglycaemia.11 On the other hand, overuse of health care also implies a clear cost/opportunity loss. In this respect, although the number of beds that a hospital or region should have may vary according to the epidemiological and socio-demographic characteristics of the population served, their availability is an essential element in dealing with moments of increased care pressure.

Overall, inappropriate hospitalisations have a high negative impact on health systems as a whole and are a major target for increasing the efficiency and safety of health services. However, in order to estimate the effectiveness of potential improvement actions, a precise estimation and close monitoring of the degree of inappropriateness of this phenomenon is necessary, which will only be possible through practical and reliable measurement tools.

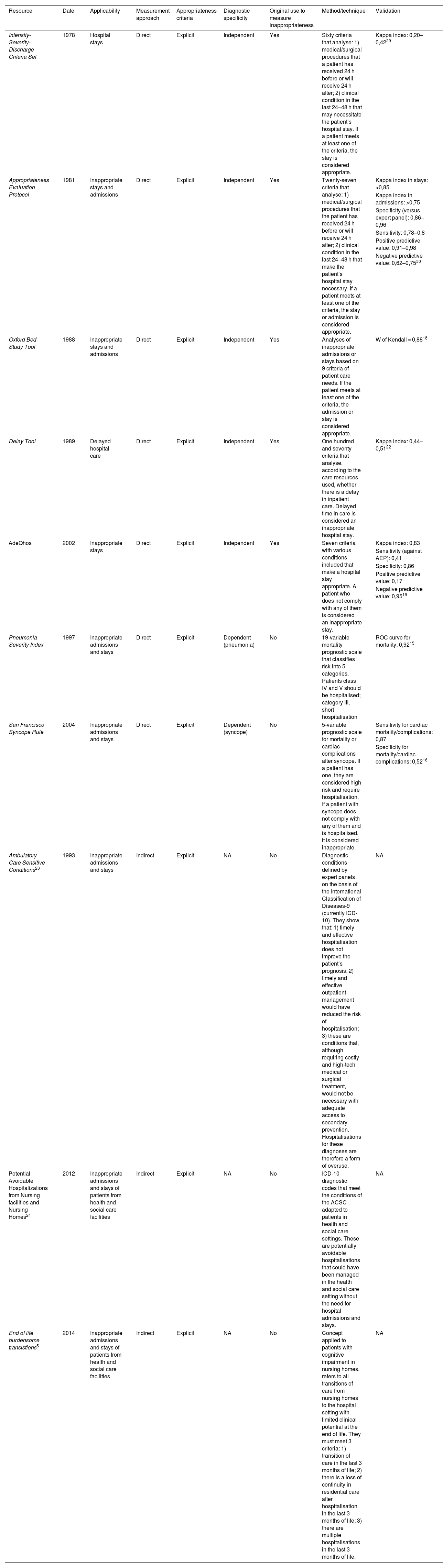

Measurement approachesThe different techniques for measuring the appropriateness of hospitalisations can be classified as direct measurement approaches, if they analyse cases individually and in a targeted way; or indirect measurement approaches, if they rely on secondary use of other data sources.12 Some of the most relevant ones are listed below (Table 1):

Ways of estimating the appropriateness of hospitalisation.

| Resource | Date | Applicability | Measurement approach | Appropriateness criteria | Diagnostic specificity | Original use to measure inappropriateness | Method/technique | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity-Severity-Discharge Criteria Set | 1978 | Hospital stays | Direct | Explicit | Independent | Yes | Sixty criteria that analyse: 1) medical/surgical procedures that a patient has received 24 h before or will receive 24 h after; 2) clinical condition in the last 24–48 h that may necessitate the patient’s hospital stay. If a patient meets at least one of the criteria, the stay is considered appropriate. | Kappa index: 0,20–0,4229 |

| Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol | 1981 | Inappropriate stays and admissions | Direct | Explicit | Independent | Yes | Twenty-seven criteria that analyse: 1) medical/surgical procedures that the patient has received 24 h before or will receive 24 h after; 2) clinical condition in the last 24–48 h that make the patient’s hospital stay necessary. If a patient meets at least one of the criteria, the stay or admission is considered appropriate. | Kappa index in stays: >0,85 |

| Kappa index in admissions: >0,75 | ||||||||

| Specificity (versus expert panel): 0,86–0,96 | ||||||||

| Sensitivity: 0,78–0,8 | ||||||||

| Positive predictive value: 0,91–0,98 | ||||||||

| Negative predictive value: 0,62–0,7530 | ||||||||

| Oxford Bed Study Tool | 1988 | Inappropriate stays and admissions | Direct | Explicit | Independent | Yes | Analyses of inappropriate admissions or stays based on 9 criteria of patient care needs. If the patient meets at least one of the criteria, the admission or stay is considered appropriate. | W of Kendall = 0,8818 |

| Delay Tool | 1989 | Delayed hospital care | Direct | Explicit | Independent | Yes | One hundred and seventy criteria that analyse, according to the care resources used, whether there is a delay in inpatient care. Delayed time in care is considered an inappropriate hospital stay. | Kappa index: 0,44–0,5122 |

| AdeQhos | 2002 | Inappropriate stays | Direct | Explicit | Independent | Yes | Seven criteria with various conditions included that make a hospital stay appropriate. A patient who does not comply with any of them is considered an inappropriate stay. | Kappa index: 0,83 |

| Sensitivity (against AEP): 0,41 | ||||||||

| Specificity: 0,86 | ||||||||

| Positive predictive value: 0,17 | ||||||||

| Negative predictive value: 0,9519 | ||||||||

| Pneumonia Severity Index | 1997 | Inappropriate admissions and stays | Direct | Explicit | Dependent (pneumonia) | No | 19-variable mortality prognostic scale that classifies risk into 5 categories. Patients class IV and V should be hospitalised; category III, short hospitalisation | ROC curve for mortality: 0,9215 |

| San Francisco Syncope Rule | 2004 | Inappropriate admissions and stays | Direct | Explicit | Dependent (syncope) | No | 5-variable prognostic scale for mortality or cardiac complications after syncope. If a patient has one, they are considered high risk and require hospitalisation. If a patient with syncope does not comply with any of them and is hospitalised, it is considered inappropriate. | Sensitivity for cardiac mortality/complications: 0,87 |

| Specificity for mortality/cardiac complications: 0,5216 | ||||||||

| Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions23 | 1993 | Inappropriate admissions and stays | Indirect | Explicit | NA | No | Diagnostic conditions defined by expert panels on the basis of the International Classification of Diseases-9 (currently ICD-10). They show that: 1) timely and effective hospitalisation does not improve the patient’s prognosis; 2) timely and effective outpatient management would have reduced the risk of hospitalisation; 3) these are conditions that, although requiring costly and high-tech medical or surgical treatment, would not be necessary with adequate access to secondary prevention. Hospitalisations for these diagnoses are therefore a form of overuse. | NA |

| Potential Avoidable Hospitalizations from Nursing facilities and Nursing Homes24 | 2012 | Inappropriate admissions and stays of patients from health and social care facilities | Indirect | Explicit | NA | No | ICD-10 diagnostic codes that meet the conditions of the ACSC adapted to patients in health and social care settings. These are potentially avoidable hospitalisations that could have been managed in the health and social care setting without the need for hospital admissions and stays. | NA |

| End of life burdensome transistions5 | 2014 | Inappropriate admissions and stays of patients from health and social care facilities | Indirect | Explicit | NA | No | Concept applied to patients with cognitive impairment in nursing homes, refers to all transitions of care from nursing homes to the hospital setting with limited clinical potential at the end of life. They must meet 3 criteria: 1) transition of care in the last 3 months of life; 2) there is a loss of continuity in residential care after hospitalisation in the last 3 months of life; 3) there are multiple hospitalisations in the last 3 months of life. | NA |

ACSC: Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions; AEP: Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol; NA: not applicable.

Implicit criteria methods: are based on an analysis of the inappropriateness of hospitalisation as judged by a panel of experts. Their main limitation is their low consistency, as they depend on subjective assessment or criteria set by the reviewers. The advantage is that they offer flexibility in analysis, allowing the assessment of very specific clinical situations for which there are no explicit criteria. Therefore, these studies are more commonly used to analyse the overuse of diagnostic or therapeutic procedures.12,13

Explicit diagnosis-dependent criteria methods: are based on the analysis of the appropriateness of hospitalisation according to explicit criteria validated in specific diseases.14 They provide a higher level of evidence than those using implicit criteria but have a more limited scope. Although hospital admissions are usually analysed globally, there are also specific diagnosis-dependent tools used to analyse admission overuse. Examples include the Pneumonia Severity Index or the San Francisco Syncope Rule, which define admission requirements for patients diagnosed with pneumonia or syncope, respectively, according to clinical criteria.15,16 These tools were originally designed to support decision-making in emergency departments but have also been used to assess overuse. On the other hand, The Medically-Ready Discharge Criteria stand out as appropriate discharge criteria in 11 specific diagnoses for paediatric patients.14 The tool was designed to reduce the length of time patients spend in hospital and can be used retrospectively to estimate unwarranted length of stay.

Explicit diagnostic-independent criteria methods: are based on the clinical situation and the patient’s care needs at the time of analysis. As an advantage, they provide overall frequencies of inappropriate hospital use. Its main limitation is that it loses the specificity of diagnosis-dependent tools for specific diseases.8

The most important validated tools are:

The Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol (AEP): is the most widely used validated tool in the analysis of hospitalisation overuse. Designed by Gertman and Restuccia in 1981,8 it has been adapted cross-culturally to multiple geographic locations. It is a tool consisting of 27 criteria covering medical/surgical procedures and the patient’s clinical condition in the 24–48 h before or after its application. If a patient meets at least one of the criteria, the stay is considered appropriate; if none of the criteria are met, the stay is considered unwarranted. This means that the tool only interprets as inappropriate hospitalisation those patients who are clinically stable and not receiving complex care, and may also underestimate the true extent of overuse, as it does not discuss the need to indicate the procedures that determine appropriateness. In addition, the protocol includes a list of possible causes of inappropriateness that allows for their stratification. The AEP was widely used in the 1980s and 1990s. Subsequently, tools adapted to more specific care settings were developed, such as paediatric (pAEP), surgical (sAEP), obstetric, admissions (aAEP) or emergency department (edAEP).17

Oxford Bed Study Instrument (OBSI): developed in the UK in the 1980s, it is based on the analysis of admissions or length of stay based on 9 criteria of patient care needs and a form of 16 possible causes of inappropriateness. Studies using the OBSI tend to find higher frequencies of inappropriateness than those using the AEP, although this tool could be considered less reliable in its measurement.18 The OBSI may be useful for recurrent monitoring of inappropriateness at hospital level, although its criteria may need to be revised.12 On the other hand, the lack of published results with this tool limits its comparability and use in the field of research.

AdeQhos: developed and validated in Spain in 2002, is aimed exclusively at analysing the inappropriateness of hospital stays. Analogous to the AEP, it is based on a review using 7 broad criteria that, if at least one is met, deem a hospital stay to be appropriate. As a distinguishing feature, its application requires a reviewer with a clinical background and specific training.19

Intensity-Severity-Discharge Criteria Set (ISD-A): designed in 1978, it has more than 60 criteria that are applied in the same way as the AEP.20 However, it has been less widely used than the latter due to: 1) its ability to detect inappropriateness is similar to the AEP; 2) its 60 criteria make it less efficient to apply; and 3) it has a lower degree of inter-reviewer agreement.21

Delay Tool: designed in the USA. In 1989. It consists of 170 criteria with which it analyses, according to the care resources used, whether there is a delay in the care of hospitalised patients, acting as a direct measurement tool of the perceived quality of care.22 Based on the time of delay in care, it allows to calculate the frequency of hospital overuse. It is still valid today.12

Indirect measurement approachesRefers to those in which an estimate of hospital overuse is made without analysing each case on a case-by-case basis. In most cases, they are measurements based on secondary use of other data sources and do not require a specific medical record review process. Its main advantage is its efficiency in using already recorded data and in classifying inappropriateness on the basis of pre-established expert criteria. The main limitation is that it does not analyse episodes individually, which may lead to a loss of sensitivity and specificity.9 These methods have been further developed in recent years. The following stand out:

The Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions (ACSC): consists of a set of diagnostic situations defined by expert panels on the basis of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Originally, they were developed as a way of assessing the quality of care and the effectiveness of outpatient care. However, its design also allows estimating, indirectly, the overuse of hospital admissions and stays, as one or more of the following characteristics are met in these situations: 1) timely and effective hospitalisation does not improve the patient’s prognosis; 2) effective and timely outpatient management would have reduced the risk of hospitalisation; and 3) these are situations that, although requiring costly and high-tech medical or surgical treatments, hospitalisation could be avoided with adequate access to secondary prevention.23

Potential Avoidable Hospitalizations from Nursing facilities and Nursing Homes: is a development of the previous concept used for hospitalisation of patients coming from nursing homes. After defining standards of care in these centres, ICD-10 disease codes are classified into potentially avoidable hospitalisations according to the criteria of the ACSC. These are therefore situations that could have been handled in the social and health care setting without hospital admissions and stays.24

Clinical practice variability: is based on the comparison of the frequency of hospitalisation between comparable health care facilities or regions. They allow hypotheses to be drawn about possible situations of overuse in cases where existing differences cannot be explained by the epidemiological and socio-demographic characteristics of each study population. In the study of hospitalisation, there are different application models: on the one hand, its variability according to process can be analysed and they have been used for a large number of diagnoses and procedures25; on the other hand, estimates of potentially avoidable hospitalisations can also be made, which have been successfully applied in many European countries. Noteworthy in Spain are the studies conducted by the Aragon Institute of Health Sciences which, through the Atlas of Variations in Medical Practice, indicate that more than 3 million hospital stays and 4% of hospitalisations could potentially be avoided. The latter would present a higher risk of occurring in diagnoses of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure or dehydration; as well as in the autonomous communities of Cantabria and the Region of Murcia.26

DiscussionThe inappropriateness of hospital admissions is an area of research of great interest for improving the quality of health care. For their knowledge and analysis, there are various approaches, with their own indications, criteria and measurement tools. Thus, the choice of one methodology or another should be made according to the objective to be achieved.12

On the one hand, diagnosis-dependent measurement approaches make it possible to analyse the hospitalisation of patients with specific diseases by means of a specific assessment of each medical record. In doing so, they provide detailed information on the resource consumption and care burden associated with specific diagnostic groups. These indicators are of great interest in the field of micromanagement, as they anticipate possible future needs and facilitate the forecasting and internal organisation of clinical management units.

On the other hand, diagnosis-independent measurement approaches are the most commonly used in the scientific literature due to their greater versatility and areas of application. In general, they tend to be used on more heterogeneous samples, providing useful information for different levels of health management and organisation. At the micro-management level, they serve as decision support for emergency departments and as a measurement tool for departments with a high frequency of multi-pathological patients (e.g. internal medicine). In middle management, they make it possible to study complete hospital samples, allowing the main causes of admissions and days of unwarranted stays in each centre to be identified. And, for macro-management, they facilitate the design and establishment of the necessary indicators to be able to promote an appropriate inter-hospital benchmarking system, as well as joint and coordinated improvement strategies.

However, regardless of their nature, the application of all these tools, as well as the interpretation of their results, should be undertaken with some caution. Their methods were designed in specific geographical and temporal settings and, although they aim to achieve the highest possible degree of external validity, they also have general limitations. One of the main ones, applicable to the whole appropriateness study in general, would be the so-called area of uncertainty12 or grey scale,9 which comprises those situations in which the appropriateness of a particular health procedure cannot be established with certainty or precision. This phenomenon can be influenced by a number of factors, such as the specific characteristics of patients or the availability of resources in each health system. In this sense, any findings of inappropriateness should be interpreted not only in the light of the theoretical model of each tool, but also in the light of the social and health context of the application environment.

Similarly, although some of these tools are still being validated and used today, most of them were designed in the 1980s and 1990s. Since then, innovation in this field of work has been minor, mostly limited to a re-adaptation of previously existing methods. This situation has not changed substantially with the rise of international initiatives which, in recent years, have drawn up lists of recommendations for clinical practice. Examples include the Do Not Do Recommendations in the UK; Choosing Wisely, originally from the USA, but also adapted by more than 30 countries; and the Compromiso por la Calidad de las Sociedades Científicas (Commitment to Quality of Scientific Societies) in Spain. Despite having the specific and shared objective of reducing the overuse of healthcare and benefiting from the collaboration of numerous scientific societies, its commitment to the problem of inappropriate hospitalisation has been limited to proposing a few specific recommendations. There is therefore room for improvement in the development, dissemination and implementation of recommendations and guidelines for clinical practice related to hospitalisation, which would also reduce the inappropriateness of other associated procedures, such as drug prescription.

The lack of innovation can have a negative impact on this area of work, as the various criteria defining the appropriateness of hospitalisation may change with the development of high-quality scientific evidence and the implementation of new health technologies that reduce risk and the need for care or clinical follow-up. In this respect, some of the most outstanding examples would be: 1) outpatient care, which enables diagnostic-therapeutic management by reducing or eliminating the need for patient hospitalisation; 2) home hospitalisation, which could constitute an effective alternative for certain profiles of elderly or chronically ill patients and which, in Spain, could reduce up to 6 days of hospital stay per patient27; 3) telemedicine (including video-consultations, telemonitoring, interactive voice response systems and structured telephone support, among others), which would achieve moderate effects in reducing hospitalization,28 and 4) and new models of continuity of care, which have also been shown to be effective for this purpose.6 Taken together, they all represent medical innovations which, for various indications, make it possible to reduce or avoid the need for hospitalisation. But, if new evidence is not incorporated into measurement methods, the reliability and acceptability of these will inevitably be compromised.

Similarly, the increase in the number and activity of social and health care centres, as a result of the progressive ageing of the population, requires the creation and adaptation of specific measurement methods for this sector. In this context, reducing potentially avoidable hospital admissions is a particularly important goal, as it would prevent new risks that do not always provide clinical benefit and improve the sustainability of the healthcare system. Some useful initiatives and resources have already been launched. An example would be End of life burdensome transitions, which comprise certain transitions of care, carried out at the end of a patient’s life, from health and social care centres to hospitals. In certain cases, the potential clinical value of this practice would be limited, being considered as a form of overuse of hospitalisation. Some authors suggest that this phenomenon occurs when transitions meet one of the following three conditions: 1) they take place in the last 3 days of life; 2) there is a loss of continuity of care in health and social care facilities after a hospitalisation in the last 3 months of life; and 3) there are multiple hospitalisations in the last 3 months of life. The frequency with which it could occur is variable, ranging from 2.1% to 37.5%.5 Another related resource would be the Do-not-Hospitalise directives understood as the indications to be followed in the final stage of life, having been agreed by the patient himself or by his legal guardians on the basis of a specific geriatric assessment. Properly implemented, this resource could also be effective in reducing the frequency of unwarranted transfers and hospitalisations of patients from social and health care facilities.

However, the absence of more modern and up-to-date methods does not invalidate the recommendation to use previously existing methods that have already been shown to have a high degree of reliability and acceptability. An example is the AEP, which is positioned as an internationally validated tool, simple and efficient to use, adapted to different care settings and compatible for estimating both the appropriateness of admissions and the number of days in hospital. In addition, it is able to identify high rates of overuse for hospital admissions, providing decision support and revealing ample room for improvement in the implementation of outpatient management systems. From the above, it can be concluded that the benefit/risk balance of its application is not only favourable, but also provides high added value for clinical and health management.

ConclusionsDue to their high incidence and the impact of their potential consequences on patient safety and system efficiency, reducing inappropriate hospitalisations is a relevant and priority objective. In order to achieve this, the criteria for their appropriateness must be specific, unambiguous and up to date.

Although numerous measurement approaches and tools exist, most of them were designed several decades ago, so they often do not incorporate new scientific evidence related to resources and techniques that have proven effective in reducing this type of overuse, such as outpatient care or telemedicine. In this respect, new methods should be developed that take into account these and other advances in health technology and innovation and that can be updated according to the new needs of the system. In the same way, social and health care is positioned as an area of great interest in this field, due to the progressive ageing of the population and the existing margin for improvement in relation to potentially avoidable hospitalisations.

In short, for the time being, there are no recently created tools that incorporate the latest innovations in healthcare practice into their criteria and are internationally validated. However, in the absence of other, more up-to-date options, the use of existing ones should be encouraged, as they have proven particularly useful in understanding and improving the appropriateness of hospitalisation as a whole.

Ethical considerationsThis work has not involved any animal, patient or human subject experimentation. It does not include a clinical trial or any experimental model. This is a narrative review of the scientific literature. It did not require informed consent.

FundingThis work has not received any funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.