The emergence of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and its subsequent pandemic spread has resulted in a global public health crisis with devastating health, social and economic consequences. The initial response of the different states was to impose restrictive measures and social barriers, such as the use of face masks or social distancing or mobility restrictions. In this context of pandemic chaos and after the rapid and celebrated development of several effective vaccines against COVID-19, following the efforts of the pharmaceutical industry and virological research laboratories, it seems that the only hope for defeating the pandemic lies in the speedy and large-scale vaccination of the population. There is no doubt that the prevention of infectious diseases through vaccination has been one of the most important advances in public health. However, it seems that scepticism towards such vaccines, framed in the context of a structural crisis of confidence in science and technology, and of scientific knowledge, whose origin predates the current pandemic, with a growing trend,1 and as expected,2 has become an additional problem in the fight against COVID-19.

Thus, reluctance to the vaccine, defined as refusal, delay or acceptance with doubts about the usefulness and safety of the vaccine, can affect a significant number of the population, which may be reluctant to vaccinate for COVID- 19, despite the clear public perception of the high health risks associated with the pandemic.3 In such a situation, different medico-legal and ethical debates emerge, as has already been happening in the course of the current pandemic, deserving special consideration.4

Firstly, at least two scenarios must be distinguished in order to address this issue: vaccination of the general population and vaccination of health professionals.

In this regard, for the general population, the eternal debate on the appropriate balance of action between coercive and persuasive measures regarding vaccination is still present. For some years now, some countries have expanded enforcement action, making vaccination mandatory. This has historically raised the question of state intrusion into the realm of individual liberty, especially with regard to parental care for their children, and therefore anti-vaccination movements have opposed it.5,6 When a fatal case is brought to public attention, the debate is fuelled, returning to its baseline over time. Therefore, it is still essential to broadly address this debate to reach a greater ethical consensus that allows obtaining the benefits of vaccination in the general population.7

On the other hand, it has been found that a possible unintended effect of compulsory vaccination could be to encourage greater reluctance. In addition, mandatory vaccination of the general population may discourage health professionals from their efforts to motivate patients to be vaccinated. In this regard, it should not be forgotten that health professionals play a central role in building trust in vaccines and their recommendations are important drivers of vaccine acceptance, when not mandatory, among vaccine-reluctant people.8 We therefore believe that the legislation underpinning compulsory vaccination for the general population should be reserved for catastrophic epidemiological situations that are difficult to manage, acting as a safety net for community health.5

Having said that, this article aims to address, due to its current controversy, the second of the proposed scenarios, which refers to the refusal of vaccination by health professionals, specifically in the case of COVID-19 vaccination. Firstly, it should be remembered that, according to some authors, Spain is one of the countries in the world with the highest number of healthcare professionals affected by COVID-19. As of 11 May 2020, a total of 40,961 cases of COVID-19 in healthcare professionals had been reported to the RENAVE network.9 SARS-CoV-2 infection has reached many healthcare professionals, exposed to unquestionable risk while doing their job.10 In addition, during the current pandemic, some professionals have had to care for patients despite difficulties in obtaining adequate personal protective equipment.4 It is a well-known fact that there has been a significant morbidity and mortality rate among healthcare professionals in Spain due to COVID-19. Despite this, these healthcare professionals still face many obstacles in various fields, including the fact that their illness has not yet been classified as an occupational disease,11 just as they deserve. On the other hand, the numerous efforts to counteract the consequences of the pandemic on health professionals are also evident. Thus, according to current ethical principles,12–14 healthcare professionals have a preferential place, with respect to prioritisation, in the COVID-19 vaccination strategy in Spain.15

On the other hand, it should be noted that healthcare professionals face an twofold ethical responsibility before society in relation to this vaccination, on the one hand as proactive agents in the generalised vaccination strategy of the group itself, that is, self-protection, extended to the protection of their patients, of their institution and of the healthcare system in general, which in itself generates confidence in the population as a consequence of the exemplary effect of health professionals in benefiting public health, due to their status as socially valued individuals and, on the other hand, as generators of confidence in the population in relation to vaccination, providing contrasted knowledge based on scientific evidence as it emerges, avoiding misinformation, resolving doubts and uncertainties and constantly re-evaluating the information available to them.16 Thus, it should be recalled that any conduct that may include recommending not to vaccinate, generating unfounded doubts, or promoting misinformation about vaccines is contrary to good professional practice.17

This said, it cannot be overlooked that, among health professionals, due to different reasons, such as the uncertainty regarding the safety of the available vaccines and, similarly to other countries, there is also some reluctance to COVID-19 vaccination, with this reluctance being, in some cases, differentiated and independent from the acceptance of other vaccines with greater use experience. In fact, this reluctance to vaccinate among healthcare professionals is not a new phenomenon,18 nor exclusive to doctors.19

Health professionals, who are generally reluctant to vaccinate, refer mainly to Royal Decree 664/1997, which states that "when there is a risk of exposure to biological agents for which there are effective vaccines, these must be made available to workers, informing them of the advantages and disadvantages of vaccination". They therefore interpret vaccination as a voluntary act of their own choice. A decision supported on ethical grounds by the exercise of the principle of autonomy, which refers to the individual capacity of all persons to decide freely, i.e., to make decisions about oneself in relation to matters that concern oneself.13

Given this situation, different possible approaches can be distinguished, from the medico-legal to the ethical or deontological perspective in order to deal with the problem raised.

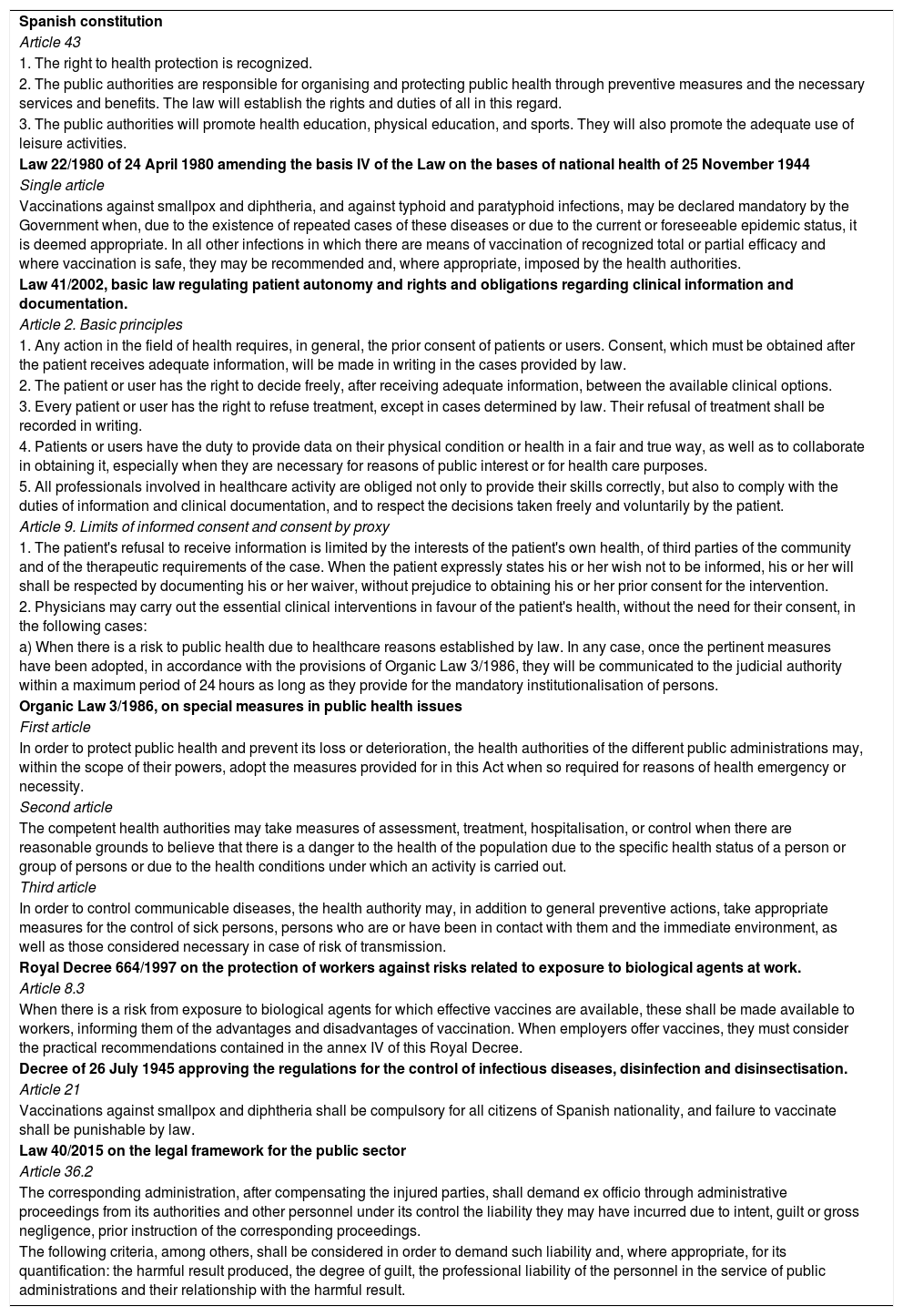

Medico-legal approach to COVID-19 vaccination reluctance in healthcare professionalsFirstly, on a legal level, even assuming the absolute impossibility of any legal debate, reference can be made to multiple legal provisions of different rank and scope currently in force in Spain that are of interest to the problem set out above and which are listed in Table 1.

Main regulations in force in Spain regarding COVID-19 vaccination for healthcare professionals.

| Spanish constitution |

| Article 43 |

| 1. The right to health protection is recognized. |

| 2. The public authorities are responsible for organising and protecting public health through preventive measures and the necessary services and benefits. The law will establish the rights and duties of all in this regard. |

| 3. The public authorities will promote health education, physical education, and sports. They will also promote the adequate use of leisure activities. |

| Law 22/1980 of 24 April 1980 amending the basis IV of the Law on the bases of national health of 25 November 1944 |

| Single article |

| Vaccinations against smallpox and diphtheria, and against typhoid and paratyphoid infections, may be declared mandatory by the Government when, due to the existence of repeated cases of these diseases or due to the current or foreseeable epidemic status, it is deemed appropriate. In all other infections in which there are means of vaccination of recognized total or partial efficacy and where vaccination is safe, they may be recommended and, where appropriate, imposed by the health authorities. |

| Law 41/2002, basic law regulating patient autonomy and rights and obligations regarding clinical information and documentation. |

| Article 2. Basic principles |

| 1. Any action in the field of health requires, in general, the prior consent of patients or users. Consent, which must be obtained after the patient receives adequate information, will be made in writing in the cases provided by law. |

| 2. The patient or user has the right to decide freely, after receiving adequate information, between the available clinical options. |

| 3. Every patient or user has the right to refuse treatment, except in cases determined by law. Their refusal of treatment shall be recorded in writing. |

| 4. Patients or users have the duty to provide data on their physical condition or health in a fair and true way, as well as to collaborate in obtaining it, especially when they are necessary for reasons of public interest or for health care purposes. |

| 5. All professionals involved in healthcare activity are obliged not only to provide their skills correctly, but also to comply with the duties of information and clinical documentation, and to respect the decisions taken freely and voluntarily by the patient. |

| Article 9. Limits of informed consent and consent by proxy |

| 1. The patient's refusal to receive information is limited by the interests of the patient's own health, of third parties of the community and of the therapeutic requirements of the case. When the patient expressly states his or her wish not to be informed, his or her will shall be respected by documenting his or her waiver, without prejudice to obtaining his or her prior consent for the intervention. |

| 2. Physicians may carry out the essential clinical interventions in favour of the patient's health, without the need for their consent, in the following cases: |

| a) When there is a risk to public health due to healthcare reasons established by law. In any case, once the pertinent measures have been adopted, in accordance with the provisions of Organic Law 3/1986, they will be communicated to the judicial authority within a maximum period of 24 hours as long as they provide for the mandatory institutionalisation of persons. |

| Organic Law 3/1986, on special measures in public health issues |

| First article |

| In order to protect public health and prevent its loss or deterioration, the health authorities of the different public administrations may, within the scope of their powers, adopt the measures provided for in this Act when so required for reasons of health emergency or necessity. |

| Second article |

| The competent health authorities may take measures of assessment, treatment, hospitalisation, or control when there are reasonable grounds to believe that there is a danger to the health of the population due to the specific health status of a person or group of persons or due to the health conditions under which an activity is carried out. |

| Third article |

| In order to control communicable diseases, the health authority may, in addition to general preventive actions, take appropriate measures for the control of sick persons, persons who are or have been in contact with them and the immediate environment, as well as those considered necessary in case of risk of transmission. |

| Royal Decree 664/1997 on the protection of workers against risks related to exposure to biological agents at work. |

| Article 8.3 |

| When there is a risk from exposure to biological agents for which effective vaccines are available, these shall be made available to workers, informing them of the advantages and disadvantages of vaccination. When employers offer vaccines, they must consider the practical recommendations contained in the annex IV of this Royal Decree. |

| Decree of 26 July 1945 approving the regulations for the control of infectious diseases, disinfection and disinsectisation. |

| Article 21 |

| Vaccinations against smallpox and diphtheria shall be compulsory for all citizens of Spanish nationality, and failure to vaccinate shall be punishable by law. |

| Law 40/2015 on the legal framework for the public sector |

| Article 36.2 |

| The corresponding administration, after compensating the injured parties, shall demand ex officio through administrative proceedings from its authorities and other personnel under its control the liability they may have incurred due to intent, guilt or gross negligence, prior instruction of the corresponding proceedings. |

| The following criteria, among others, shall be considered in order to demand such liability and, where appropriate, for its quantification: the harmful result produced, the degree of guilt, the professional liability of the personnel in the service of public administrations and their relationship with the harmful result. |

It is clear from a simple reading of this legislation that public health is one of the main limits to individual freedom in defence of the collective interest. Thus, the constitutional mandate to protect public health requires public authorities to articulate mechanisms to protect the population from contagious diseases. Healthcare professionals have an obligation to prevent the spread of infectious diseases and to minimise the harm that could be caused should they materialise. Thus, Article 43 of the Spanish Constitution provides an appropriate legal basis for enforcing obligations on the health care system when the defence of collective health is clearly justified.20 Even so, this article may come into conflict with Article 16 of the Magna Carta, which guarantees respect for the autonomy of will and the validity of ideological freedom.

However, as is clear from the brief articles of Law 3/1986, on special measures in the field of public health, the health authorities are recognised as competent to adopt exceptional measures when required for urgent or necessary health reasons, provided that there are rational indications that suggest the existence of a danger to the health of the population due to the specific health situation of a person or group of people, or in order to control communicable diseases. In fact, this situation had already been regulated in the case of smallpox and diphtheria infections and, more recently, exceptional measures were also applied during the state of alarm.

Thus, another medico-legal aspect that the pandemic has brought to the fore was the involuntary institutionalisation of COVID-19 patients for public health reasons.4 Previously, such situations had occurred in isolation in the context of, for example, therapeutic hospitalisation in the control of tuberculosis.21 In this case, it is the same Law 3/1986, on special measures in the field of public health, which recognises the competence of the health authorities to adopt measures (of recognition, treatment, hospitalisation or control), when required for emergency or necessary health reasons, provided that there are rational indications that suggest the existence of a danger to the health of the population due to the specific health situation of a person or group of persons, or in order to control communicable diseases.

Moreover, it should be noted that the Law on patient autonomy and on rights and obligations regarding clinical information and documentation also provides for the possibility of clinical interventions being carried out without the patient's consent when there is a risk to public health, requiring that these interventions, carried out under Law 3/1986, be brought to the attention of the competent legal authority if they involve forced institutionalisation.22

With regard to COVID-19 vaccination, it should be noted that there are already legal precedents in Spain that enforce vaccination in a case of reluctance by proxy, on the grounds of the patient's own interest.

Thus, faced with the legal dilemma of whether the right of the health professional to opt for non-vaccination should prevail over the right of patients to the protection of their health, that is, over their right not to be infected by the health professionals who treat them with a disease of which they are carriers, the opinion of some jurists on the matter,23 after an exhaustive analysis of the legal and regulatory standards, is clear: in the face of a collision of rights, according to the teleology of all available legislation, the right of patients not to be infected must prevail. From this would derive the legitimacy of imposing by law the obligation to vaccinate on health professionals, except for any specific incompatibilities or contraindications that may exist.

Finally, it can be added that, if damage were to occur to third parties, such as transmission due to non-vaccination, it would imply a breach of the duties and rules that apply to health professionals, which could lead to professional liability, and in accordance with article 36. 2 of Law 40/2015 of the public sector which states that the Administration convicted for the transmission of a disease through a health professional who has not been duly vaccinated and who has incurred intent, guilt, or gross negligence, can automatically act against the person who caused the transmission, i.e., the health professional, by virtue of the action of recourse provided for.

Ethical approach to COVID-19 vaccination reluctance in healthcare professionalsBioethical analysis is based on the deliberative method, during which it is essential to identify conflicting values, extreme courses of action and intermediate courses, in order to be able to establish the optimal course or courses of action. The latter would answer the question of what is most proportionate and prudent, two key words in bioethics, i.e., which action would least harm the values at stake and most appropriately weigh the circumstances and consequences.

In the reluctance to COVID-19 vaccination in health professionals, we would find different values and principles in conflict. On the one hand, as mentioned above, a group of values and principles related to the protection of health, both collective and individual, are identified. Physicians should be guided by the principle of ensuring the health of both populations and patients, with an obligation to 'do no harm'. Generalized vaccination of healthcare professionals could prevent infections in a healthcare context. In this sense, one would also identify a duty to prioritise the interests of the persons cared for above one's own, but this would be a duty with certain limitations. Also, a side effect of vaccinating health professionals is the example it sets in promoting confidence in vaccination among the general public.

But, on the other hand, we find the group of values related to individual freedom and autonomy, which also applies in this case to the health professional himself, in relation to his own health decisions.

The assessment of whether vaccination should be compulsory cannot be separated from the particular time and circumstances of the pandemic. Many professionals assumed a high risk of transmission by working without having the appropriate protective equipment, mainly during the first weeks of the pandemic. In a way, health systems failed in their duty to protect their professionals.

Despite this, the response of healthcare professionals to the challenges posed by the pandemic has been commendable. Many professionals have made an extra effort, with changes in timetables, work environment, and all this with flexibility, availability, and high professional commitment. Health professionals have more than proved their commitment to caring for people, even assuming personal risk and professional, psychological, and ethical overload. In this context, the obligation to be vaccinated could be interpreted as a mistrust towards professionals.

It should also be noted that, unlike in other situations of vaccine reluctance, in the case of COVID-19, many of the reasons relate to confidence in the safety of vaccination, rather than denialist claims.

The two extreme approaches are clear: on the one hand, the obligation to vaccinate health professionals, and on the other hand, the recognition of the individual autonomy of the professional in relation to vaccination.

All those actions that encourage and promote the vaccination of professionals would appear as intermediate approaches. In this regard, there are already various ethical analyses24 on the role that nudges can play in the vaccination of health professionals. A nudge is defined as a "small push" that can help make better decisions in public health, influencing through the design of a choice architecture, which can influence and modify the behaviour of health professionals without excluding other options.25

These intermediate approaches could offer strategies aimed at vaccine training, internal vaccination promotion campaigns or individual risk identification according to the workplace rather than on a generalised basis. As highlighted by the Nuffield Council of Bioethics,26 in public health it is important to develop a so-called intervention ladder, from the least intrusive to the most coercive strategy, but bearing in mind that the more intrusive an intervention is, the stronger the justification must be.

Deontological approach to COVID-19 vaccination reluctance in healthcare professionalsVaccine reluctance in health professionals must also be addressed from a deontological perspective. Thus, it should be noted that the various deontological codes in force27,28 contain various articles of particular interest in relation to the present problem. Article 5.1 of the Code of Medical Ethics of the Spanish Medical Association (OMC)27 is relevant in this respect: "The medical profession is at the service of the human being and society. Respect for human life, for the dignity of the person and for the health care of the individual and the community are the primary duties of the physician". In the same sense, article 1 of the Code of Ethics of the Consell de Col·legis de Metges de Catalunya (CCMC)28 states that: "The physician must bear in mind that the objective of the practice of medicine is to promote, maintain or restore the individual and collective health of people, and must consider that health is not only the absence of disease, but also the set of physical, psychological and social conditions that allow the maximum fulfilment of the person, so that he or she can have an autonomous development".

Article 102 of the Code of Ethics of the CCMC28 can also be cited: "A physician who knows that another physician, because of his or her health status, habits or possibility of transmission, may be harmful to patients, has the duty, with the necessary discretion, to inform him or her of this and to recommend the best course of action, and also has the duty to inform the College of Physicians. The good of the patients must always be a priority". Article 22.3 of the WTO Code of Medical Ethics expresses the same view.27

However, at present, it is important to note that studies show high efficacy figures for different types of vaccines in preventing infection in the vaccinated person, but it is not yet known whether COVID-19 vaccination prevents transmission. That is, at present, we know that a vaccinated person is more protected from the disease, but it is unknown whether a vaccinated person can transmit the disease. Therefore, at present, it is not yet established that vaccination prevents a direct risk of transmission to patients.

From a deontological point of view, a health professional's decision not to vaccinate would affect his or her own health, herd immunity and exemplarity, and is therefore highly recommended, but it is not clear that it would cause direct harm to the patient.

On the other hand, it is a deontological responsibility of the doctor, in relation to vaccination, to generate confidence in it, using evidence-based knowledge when available, avoiding the dissemination and promotion of misinformation.

ConsiderationsThus, as stated above, healthcare professionals have a legal obligation, backed by a broad legal framework, to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, and to minimise the harm that may be caused if they materialise, in order to preserve the individual and collective health of people, or in other words, patients have the right to receive medical care in the best possible conditions that ensure the lowest possible risk of infection.29 With this in mind, there can be no doubt that vaccination is the current best preventive measure to achieve individual and community health protection, reducing transmission and preventing deaths from the virus effectively and efficiently. For this reason, it is recognized as a duty of the health professional, among others, the very application of vaccines that, due to the specific activity they carry out, are recommended, as has historically been the case with the vaccines against hepatitis B or influenza and, currently, against COVID-19. We are facing an exceptional state of affairs and the measures to be taken must also be exceptional. The recommendations and attitudes of health professionals in relation to the vaccine are part of good professional practice. That said, it cannot be overlooked that voluntary vaccination of health professionals is the ideal scenario. In this sense, possible initiatives have been pointed out regarding the communication of key messages to encourage vaccination, such as: help those you love the most (based on the desire to protect and help friends and family), approved by medical personnel (using the credibility and authority of the health personnel), let us return to normality (taking advantage of the motivation to return to normality), proven by thousands (generating confidence in the process) and confidence in the vaccine (guaranteeing its constant evaluation). In parallel, the Vaccine Equity Declaration promoted by the World Health Organization, calls on governments, pharmaceutical companies, regulatory agencies, and world leaders to join forces to accelerate the equitable distribution of vaccines around the world, especially among healthcare personnel.30

However, if vaccination rates guaranteeing pandemic control are not achieved through voluntary vaccination, the obligation to vaccinate health workers is morally justified29 on a proportional and individualised basis, depending on the risk. Professionals working with patients at risk who refuse to be vaccinated have also been recommended to change their workplace.

ConclusionThe medico-legal, ethical, and deontological approach to COVID-19 vaccination refusal in health professionals support the duty of such vaccination, once the public health reasons and the current context of exceptionality due to the COVID-19 pandemic have been considered, taking into account the current scientific evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of the available vaccines. The existing legal framework and legislation is sufficient to support such a claim and there is a deontological responsibility in healthcare professionals to uphold it. From an ethical point of view, it would be important to promote actions that encourage the vaccination of professionals, before considering an extreme course of action.

FundingThere have been no external funding sources.

Please cite this article as: Martin-Fumadó C, Aragonès L, Esquerda Areste M, Arimany-Manso J. Reflexiones médico-legales, éticas y deontológicas de la vacunación de COVID-19 en profesionales sanitarios. Med Clin (Barc). 2021;157:79–84.