In recent decades, the implementation of information systems to support clinical care has led to the massive collection of data.1 Just their availability represents opportunities for analysis and the generation of support information for management decision making. These data, observational in nature, have been called real-world data (RWD) and, considering their potential use, it has been proposed to define them as "data used for decision-making that are not collected in conventional randomised clinical trials".2

In turn, in the field of drug products, the intense therapeutic innovation of recent years has been accompanied by growing uncertainty about the efficacy and safety of new drugs in the real world.3 Precision medicine has conditioned that the population exposed to the new drug, at the time of authorization, is often less than usual, in addition, the accelerated or conditional authorization of products that have not completed their development, determines the need to confirm their benefit/risk ratio after marketing.4 The value of these developments is defined as the health outcomes achieved by the costs generated, therefore, it is necessary that health systems measure the health outcomes provided by the new drugs in terms of effectiveness and safety, and confirm that the expected improvement in the health of all patients is achieved, so as to guide the investment of resources that society is providing for this purpose.5

The RWD collected in routine clinical practice through healthcare applications or ad hoc databases, allow to describe patterns of use, effectiveness and safety of therapeutic interventions during their clinical use. Therefore, they can potentially be useful for completing information on newly marketed drugs, and as a feedback tool in decision making, provided that the information is thorough and homogeneous, and is obtained from a structured clinical record or data repository that allows to respond to the predefined purpose and objectives.2,5–7 The structure of a record should be determined by the questions it seeks to answer and, to ensure its suitability, the phases of design, implementation, operation and maintenance of the registry are key. In all of them, a multidisciplinary collaboration between clinical healthcare professionals, information systems specialists and those responsible for administrative management, as well as having epidemiological and statistical experience and managerial involvement is advantageous.8

However, the results in clinical practice depend largely on the type of use given to drugs and their preferred indication in one or other group, so that any estimate of effectiveness derived from observational data is vulnerable to multiple biases in the absence of experimental designs. Although there are various adjustment methodologies to control these biases, the information available for this is limited to those parameters collected in the databases, so that the ability to adjust the models may not be sufficient to guarantee a robust and bias free conclusion.7,9 Even so, the analysis of RWD has as its main advantage the obtaining of information from broader and heterogeneous populations, it offers opportunities to fill in information gaps of authorized products based on unconventional developments, and they inform in a pragmatic way of the final effectiveness of the treatments in our real clinical environment.

The usefulness of administrative records and databases as support tools for decision-making in the management of health systems is well established and described, and there are reviews and recommendations on the data requirements for this purpose.10 However, references to the application of health records as management tools in the control of pharmaceutical benefits and as a support tool for actions to promote rational use are scarce and not very specific.10,11 One of the few experiences reported in this regard is that of the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA), which uses drug registries to manage access to innovation.9,12–14 At national level, the Valencian Community also has a clinical data collection system linked to the prescription of certain high impact drugs, in line with the pharmacotherapeutic protocols that the community approves. On the other hand, the Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare created a specific disease registry in 2015, the "Therapeutic Monitoring Information System for Patients With Chronic Hepatitis C" (SITHepaC)15 and, currently, it is designing the "Information System to determine the therapeutic value in real clinical practice of high health and economic impact drugs in the National Health System" (VALTERMED)16; in both cases, they include the collection of clinical data related to the use of drugs throughout the national territory. During the last decade, Catalonia has opted for the use of registries in the management of drugs, considering that it represents an opportunity to generate and share information among the agents involved in the use of drugs (doctors, pharmacists, institutions, regulators, evaluation agencies, industry and patients), and that allows to know the true value of the innovations through the estimation of results and costs, as well as, to include the information in the decision making. In this article we gather the experience of the Servei Català de la Salut (CatSalut).

Management of the pharmaceutical provision in CataloniaIn Catalonia, the health system has publicly owned and government-subsidized centres, which constitute a network of public use hospitals under the umbrella of the Integrated Public Healthcare System of Catalonia (SISCAT).17 CatSalut is the entity that manages the public health system in Catalonia through the contracting of health services to providers based on principles of equity, quality and sustainability, adapting the offer to the needs of the population.18 These contracts include the consideration for results, a system of variable remuneration subject to the achievement of organizational, clinical and health results related to the main goals of the Pla de Salut de Catalunya, specified in the annual objectives.19 To evaluate its achievement, it is necessary to have adequate information systems to objectify the proposed evaluations and common management systems throughout the territory.

The pharmaceutical provision represents a high proportion of the health budget (more than 24% in 2017),20 so the rational use of drug products is part of the contractual objectives. Rational use principles and pharmaceutical provision management systems are generated in the Pharmacotherapeutic Harmonization Program (PHF, for its acronym in Catalan), which began in 2008. It focuses on highly complex drugs and has progressively consolidated and expanded to include the evaluation of all innovative medicines.21

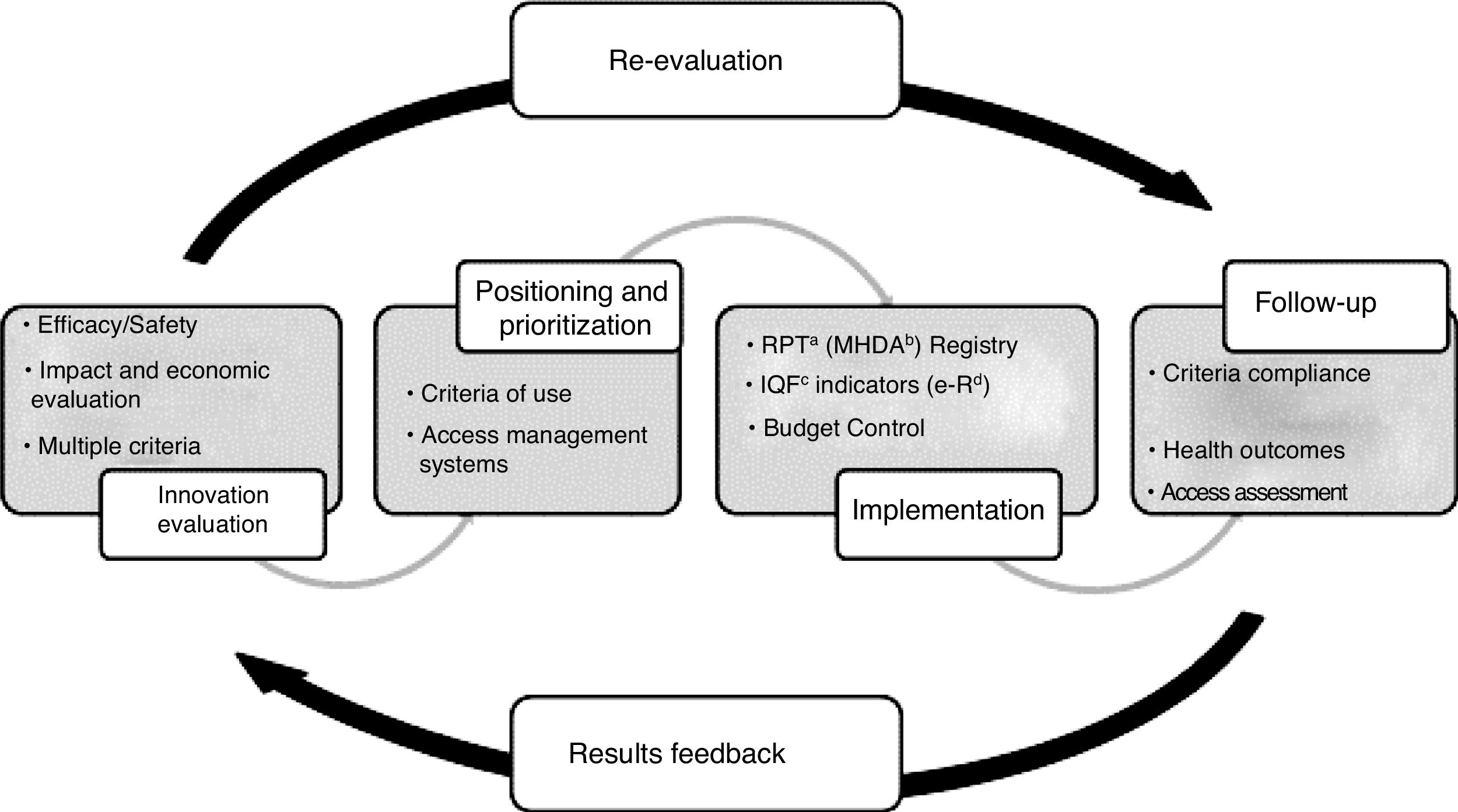

The purpose of the PHF is to guarantee equity in access to innovative medicines in accordance with the principles of rational use and considering the availability framework and the necessary optimization of resources. The added value of the drug is assessed with respect to the available alternatives, the existing uncertainties regarding the drug's efficacy and safety evidence and the potential impact in clinical and economic terms and, based on this, criteria for use, access and provision are defined according to its therapeutic positioning and prioritization. These criteria are associated with implementation measures and the collection of the information necessary for its monitoring. Finally, the information generated is used to evaluate the implementation of the criteria, the health results obtained and the real budget impact, and thus provide feedback on the decision-making process (Fig. 1). For hospital outpatient drugs (HOD), the evaluation procedure regarding harmonization is specified in three possible categories: use according to clinical criteria, individual authorization or exceptional use.21,22

HOD, unlike prescription medication, is acquired and dispensed in hospital centres, and CatSalut is billed monthly and in detail for each patient. As a service management tool, but also for the implementation and monitoring of the criteria defined for each drug evaluated by the PHF, a specific registry was created, the Patient and HOD Treatment Registry.22

Creation of the patient and treatment registrySince the beginning of the PHF, more than a decade ago, the need to have information on the use in real clinical practice of HOD became evident, so as to quantify and qualify their use, and thus provide feedback on the planning and management of access to these drugs. Unlike the electronic prescription system, which has a unique and integrated information system for the entire SISCAT, for HOD in the SISCAT hospital network there is a great diversity of prescription, information and data collection systems, which makes it difficult to obtain homogeneous information.

When creating the PHF, in 2008, and due to the variability of systems, it was decided to create a specific registry, the Patient Registry, which piloted a collection of basic information on the clinical indication and the duration of treatment in connection with 30 drugs intended for haematology-oncology indications. This first experience, of a voluntary nature for the centres, allowed to obtain data on the use of these drugs and to make comparisons between hospitals, and laid the foundations for the further development of a broader registry.

During 2011, the current Patient and HOD Treatment Registry (RPT-HOD) was designed, a single specific and centralized registry for all SISCAT hospitals, with the objective of systematically collecting information on the use, effectiveness and safety of HOD under conditions of routine clinical practice, as well as the degree of adherence to the criteria defined by the PHF.22 The registry began in December 2011, with various theoretical and practical training sessions that took place over 4 months aimed at representatives of hospital pharmacy services, clinical services and medical management of SISCAT hospitals, with the participation of more than a hundred professionals. A testing phase of the new registry was carried out between April and May 2012, to validate the adequacy of the registry's design and functioning in the field of healthcare and in the routine clinical practice; as a result, various improvements were made to the information collection system. The correct harmonized product registration was envisaged to be mandatory when the RPT-HOD was created, so as to be able to invoice the drug product. However, the link between registration and invoicing was gradually implemented and agreed with hospitals and was not generally required until 2014.

The registry has progressively included new drugs and indications annually, the year with the most novelties was 2014 (n = 123 indications), followed by the years 2012, 2013, 2015 with around 90 novelties per year. During 2015, the volume estimates made at the time of design were exceeded and associated with performance problems of the application. For this reason, and in order to improve performance, in 2016 an internal redesign of the application was carried out that divided the access to the data in sections (sub-registries by disease); a similar experience has been reported by the AIFA registry.9

Operational and functional characteristics of the Registry of Patients and TreatmentsThe RPT-HOD was created in the environment of the standard healthcare registry platform that include various health registries of the Department of Salut in a safe and suitable environment as a high sensitivity data repository.

Data input to the RPT-HOD can be done online, through the Webservice system or by sending structured files. For any modality, the access to the RPT-HOD is individualized, with access privileges restricted to the information registered in the user's scope and is obtained by centralized and explicit authorization of the person responsible for the RPT-HOD of CatSalut. Currently, most centres send data through Webservice.

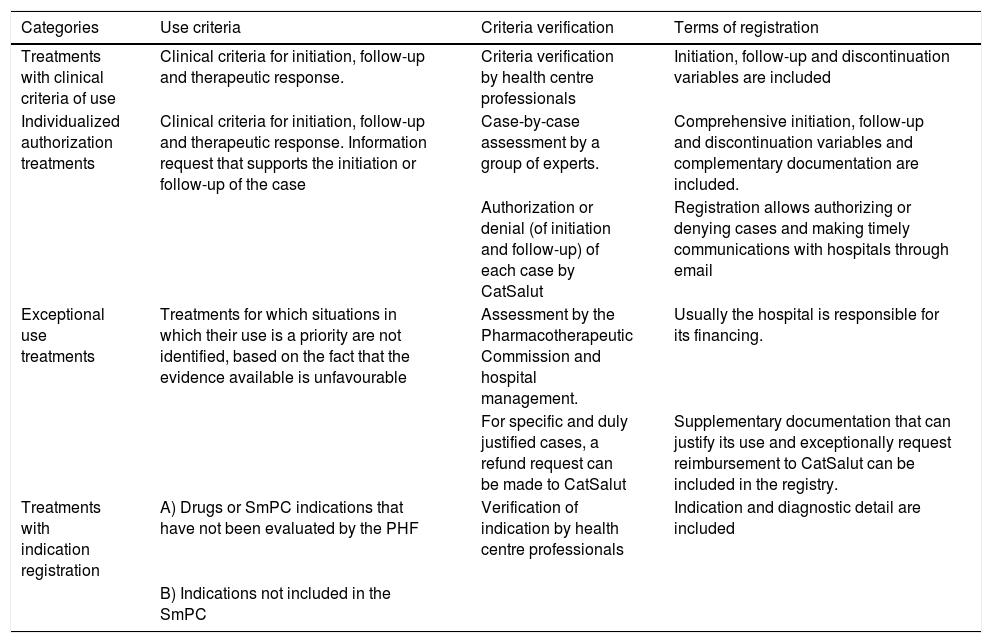

In compliance with CatSalut's directive 01/2011,22 the link between the criteria for the use of harmonized drugs and the conditions of registration is established (Table 1).

Categories and conditions of the treatment registry.a

| Categories | Use criteria | Criteria verification | Terms of registration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments with clinical criteria of use | Clinical criteria for initiation, follow-up and therapeutic response. | Criteria verification by health centre professionals | Initiation, follow-up and discontinuation variables are included |

| Individualized authorization treatments | Clinical criteria for initiation, follow-up and therapeutic response. Information request that supports the initiation or follow-up of the case | Case-by-case assessment by a group of experts. | Comprehensive initiation, follow-up and discontinuation variables and complementary documentation are included. |

| Authorization or denial (of initiation and follow-up) of each case by CatSalut | Registration allows authorizing or denying cases and making timely communications with hospitals through email | ||

| Exceptional use treatments | Treatments for which situations in which their use is a priority are not identified, based on the fact that the evidence available is unfavourable | Assessment by the Pharmacotherapeutic Commission and hospital management. | Usually the hospital is responsible for its financing. |

| For specific and duly justified cases, a refund request can be made to CatSalut | Supplementary documentation that can justify its use and exceptionally request reimbursement to CatSalut can be included in the registry. | ||

| Treatments with indication registration | A) Drugs or SmPC indications that have not been evaluated by the PHF | Verification of indication by health centre professionals | Indication and diagnostic detail are included |

| B) Indications not included in the SmPC |

PHF: Pharmacotherapeutic Harmonization Program (PHF, for its Catalan acronym).

The general structure of the registry consists of three levels of information:

- Treatment level: includes basic patient data (linked to the Central Registry of Persons Covered by CatSalut23), the identification of the treatment (drug, treatment initiation and end date, therapeutic indication and related ICD-10 diagnosis) and identification of the origin of the prescription (hospital and prescribing physician).

- Initiation level: It includes the clinical variables that are required when initiating a treatment and, if required, clinical documents may be attached.

- Follow-up level: It includes the clinical variables that are required during the treatment follow-up (according to the established frequency) and the discontinuation variables at the end of the treatment. If required, clinical documents may be included.

The treatment level is mandatory for all drugs. The initiation or follow-up level is only mandatory for drugs harmonized by the PHF.

The registry includes a basic duplicity control, which blocks the creation of records with the same treatment (drug and indication) for the same patient during the same time period. On the other hand, to allow invoicing, it checks that the treatment is correctly registered (initiation level and mandatory variables, if applicable) and active in the time period.

The new HODs and the new indications that are included in the pharmaceutical provision of the National Health System of the therapeutic groups selected through clinical and economic relevance criteria are entered monthly. On the other hand, and conditioned on the activity of the PHF, the design and incorporation of the variables for the evaluated drugs are scheduled. The variables included in each drug are defined and agreed as part of the harmonization process, with the participation of clinical experts in the disease and in the treatment under evaluation. For each case, the number of variables to be recorded is optimized, including the minimum number of variables that provide the necessary information to: 1) verify compliance with the PHF criteria, and 2) assess effectiveness and safety. They are mostly mandatory and with predetermined closed-ended values (yes/no, single selection or multiple selection). The follow-up frequency is also established, under the principle of adapting all the criteria to routine clinical practice as far as possible. The variables and their frequency are published on the PHF website. In general, the variables are parameterized and notified to the centres, with an implementation grace period related to the invoicing linkage agreed with the hospitals, and which considers the usual frequency of care visits.

User manuals and technical specifications are available as support for the RPT-HOD, and an email address for inquiries or issues is checked and answered daily.

Data analysis and evaluation of resultsAs of 31 st December 2018, the registry includes information on 587 indications that correspond to a total of 180 different drugs. 60% are indication-only treatments, 34% of clinical criteria, 3% of individualized authorization and 3% of exceptional use.

The registry includes 234,416 registered treatments for 148,184 patients, prescribed by a total of 3,481 doctors in 61 hospitals. The age of the patients at the beginning of each treatment, mean (standard deviation [SD]) is 51.84 (17.29) years and 58.36% are men. The age range, per fifteen-year period, in which more treatments have been initiated is 45–59 years, for both sexes.

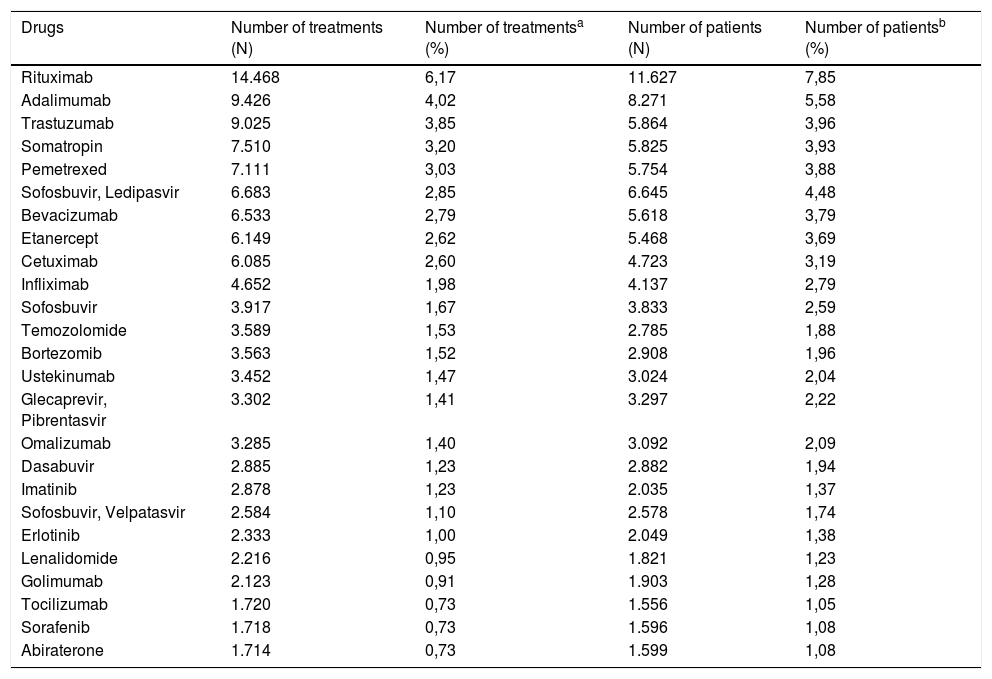

The drugs with the highest number of registered treatments are rituximab, adalimumab, trastuzumab, somatropin and pemetrexed; the drugs with the highest number of registered patients are rituximab, adalimumab, sofosbuvir-ledipasvir, trastuzumab and somatropin (Table 2).

Number of treatments and patients of the 25 most registered drugs.

| Drugs | Number of treatments (N) | Number of treatmentsa (%) | Number of patients (N) | Number of patientsb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rituximab | 14.468 | 6,17 | 11.627 | 7,85 |

| Adalimumab | 9.426 | 4,02 | 8.271 | 5,58 |

| Trastuzumab | 9.025 | 3,85 | 5.864 | 3,96 |

| Somatropin | 7.510 | 3,20 | 5.825 | 3,93 |

| Pemetrexed | 7.111 | 3,03 | 5.754 | 3,88 |

| Sofosbuvir, Ledipasvir | 6.683 | 2,85 | 6.645 | 4,48 |

| Bevacizumab | 6.533 | 2,79 | 5.618 | 3,79 |

| Etanercept | 6.149 | 2,62 | 5.468 | 3,69 |

| Cetuximab | 6.085 | 2,60 | 4.723 | 3,19 |

| Infliximab | 4.652 | 1,98 | 4.137 | 2,79 |

| Sofosbuvir | 3.917 | 1,67 | 3.833 | 2,59 |

| Temozolomide | 3.589 | 1,53 | 2.785 | 1,88 |

| Bortezomib | 3.563 | 1,52 | 2.908 | 1,96 |

| Ustekinumab | 3.452 | 1,47 | 3.024 | 2,04 |

| Glecaprevir, Pibrentasvir | 3.302 | 1,41 | 3.297 | 2,22 |

| Omalizumab | 3.285 | 1,40 | 3.092 | 2,09 |

| Dasabuvir | 2.885 | 1,23 | 2.882 | 1,94 |

| Imatinib | 2.878 | 1,23 | 2.035 | 1,37 |

| Sofosbuvir, Velpatasvir | 2.584 | 1,10 | 2.578 | 1,74 |

| Erlotinib | 2.333 | 1,00 | 2.049 | 1,38 |

| Lenalidomide | 2.216 | 0,95 | 1.821 | 1,23 |

| Golimumab | 2.123 | 0,91 | 1.903 | 1,28 |

| Tocilizumab | 1.720 | 0,73 | 1.556 | 1,05 |

| Sorafenib | 1.718 | 0,73 | 1.596 | 1,08 |

| Abiraterone | 1.714 | 0,73 | 1.599 | 1,08 |

HIV treatments, registered with an exceptional information structure, are excluded from the analysis.

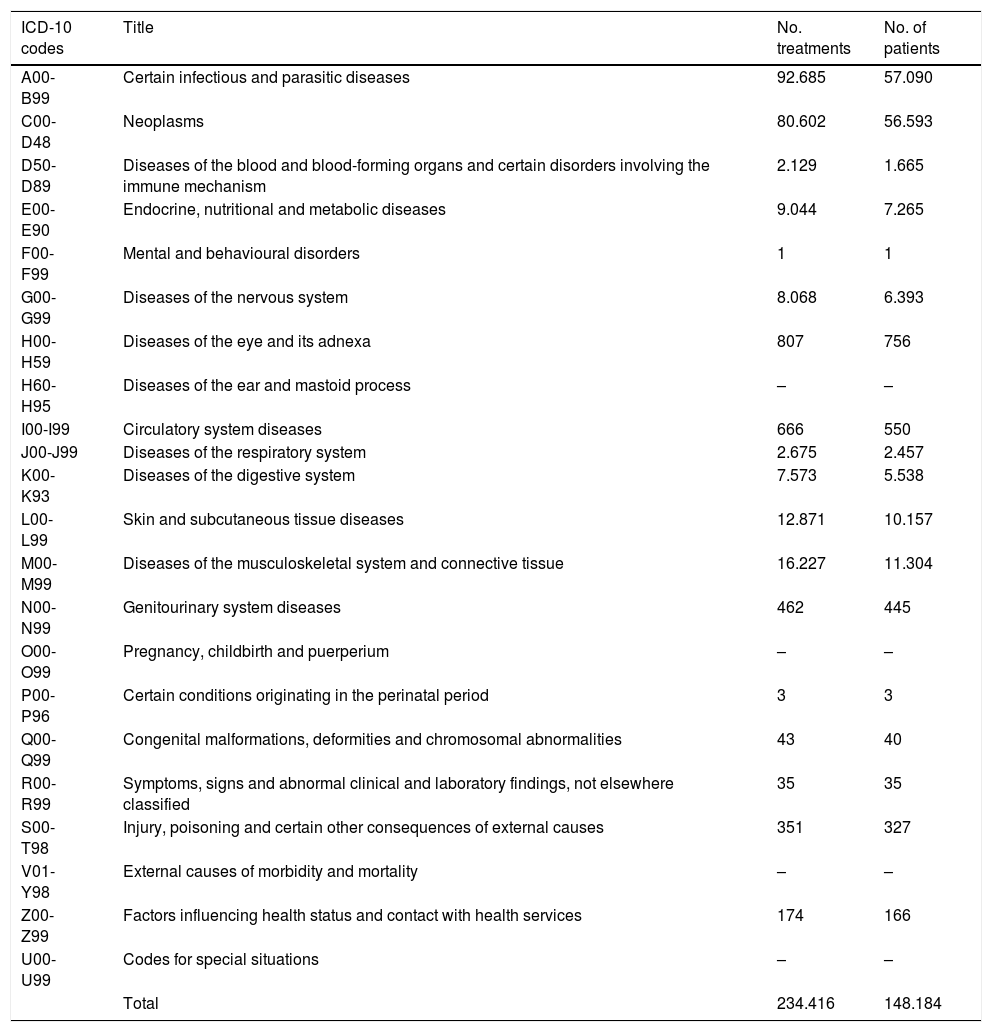

Diagnoses, classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), with the highest number of treatments and patients correspond to infectious and parasitic diseases (which include treatments for HIV and hepatitis), followed by the group of neoplasms (Table 3).

Number of treatments and patients according to the ICD-10 diagnostic classification.a

| ICD-10 codes | Title | No. treatments | No. of patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| A00-B99 | Certain infectious and parasitic diseases | 92.685 | 57.090 |

| C00-D48 | Neoplasms | 80.602 | 56.593 |

| D50-D89 | Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism | 2.129 | 1.665 |

| E00-E90 | Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | 9.044 | 7.265 |

| F00-F99 | Mental and behavioural disorders | 1 | 1 |

| G00-G99 | Diseases of the nervous system | 8.068 | 6.393 |

| H00-H59 | Diseases of the eye and its adnexa | 807 | 756 |

| H60-H95 | Diseases of the ear and mastoid process | – | – |

| I00-I99 | Circulatory system diseases | 666 | 550 |

| J00-J99 | Diseases of the respiratory system | 2.675 | 2.457 |

| K00-K93 | Diseases of the digestive system | 7.573 | 5.538 |

| L00-L99 | Skin and subcutaneous tissue diseases | 12.871 | 10.157 |

| M00-M99 | Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 16.227 | 11.304 |

| N00-N99 | Genitourinary system diseases | 462 | 445 |

| O00-O99 | Pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium | – | – |

| P00-P96 | Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period | 3 | 3 |

| Q00-Q99 | Congenital malformations, deformities and chromosomal abnormalities | 43 | 40 |

| R00-R99 | Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified | 35 | 35 |

| S00-T98 | Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes | 351 | 327 |

| V01-Y98 | External causes of morbidity and mortality | – | – |

| Z00-Z99 | Factors influencing health status and contact with health services | 174 | 166 |

| U00-U99 | Codes for special situations | – | – |

| Total | 234.416 | 148.184 |

The registry data analysis began in 2016, with two main phases: 1) result evaluation reports according to drug or disease and 2) definition and analysis of indicators of consideration for results based on effectiveness results related to 5 groups of drugs.

Data analysis reports aimed at assessing the effectiveness of antiviral treatments for hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus and the first indication of biological drugs for patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) were initially performed. From these, the first indicators of rational use of HOD included in the objectives of consideration for results were obtained. Data extractions were treated descriptively and discussed with PHF clinical experts for each therapeutic area prior to presentation to the PHF committees.

A more structured activity began in 2017, with the preparation of analysis protocols and standardized formats for public dissemination. Thus, the current result evaluation reports include history, methodology, description of the population treated, degree of compliance with the agreement, effectiveness, treatment duration and reason for discontinuation, costs and budgetary impact, comparison with the evidence used in harmonization, analysis of heterogeneity in territorial use and conclusions. Seven reports have been published on the PHF website (HCV, RA, primary hypercholesterolemia or mixed dyslipidaemia, rare diseases and 3 haematology-oncology indications).24

Reports have also been prepared on high/complexity and individualized authorization treatments for rare diseases (nocturnal paroxysmal haemoglobinuria, Fabry disease and Gaucher disease type I and III); to avoid the possible identification of cases, which would be potentially traceable due to the few patients analysed, they are not published on the CatSalut website. Dissemination of these reports is made exclusively to the expert committees of the PHF and to the professionals responsible for the cases.

Another area for the management of access to innovative medicines which CatSalut has promoted in recent years has been the risk-sharing or payment-for-results agreements for drugs with uncertainty in criteria of effectiveness, safety or budgetary impact. For the management of these agreements, it is key and essential to have the clinical information that allows the analysis of the established results and conditions, therefore, the RPT-HOD has been decisive regarding their implementation in all SISCAT hospitals.25,26

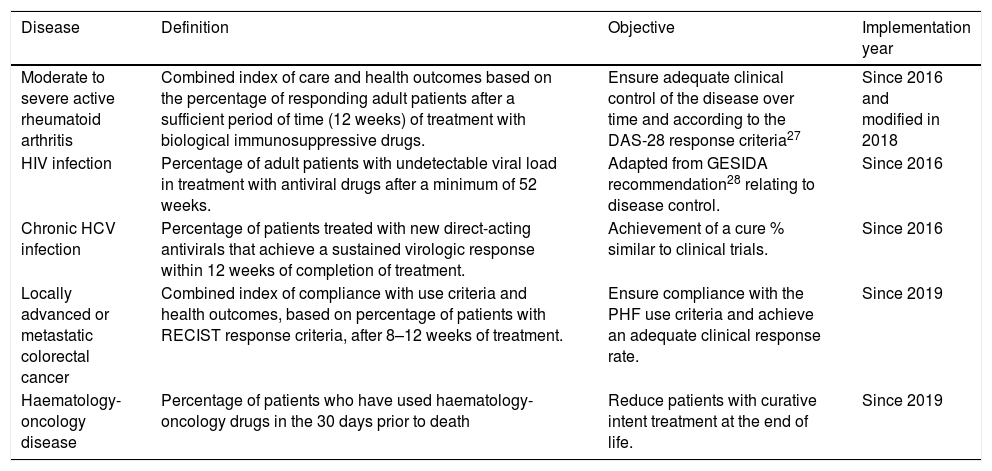

On the other hand, within the framework of contractual considerations to hospitals, rational use indicators for HOD based on effectiveness results have been developed for monitoring activity and quality in the contracting of health services (Table 4).

Indicators of consideration for results based on effectiveness.

| Disease | Definition | Objective | Implementation year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate to severe active rheumatoid arthritis | Combined index of care and health outcomes based on the percentage of responding adult patients after a sufficient period of time (12 weeks) of treatment with biological immunosuppressive drugs. | Ensure adequate clinical control of the disease over time and according to the DAS-28 response criteria27 | Since 2016 and modified in 2018 |

| HIV infection | Percentage of adult patients with undetectable viral load in treatment with antiviral drugs after a minimum of 52 weeks. | Adapted from GESIDA recommendation28 relating to disease control. | Since 2016 |

| Chronic HCV infection | Percentage of patients treated with new direct-acting antivirals that achieve a sustained virologic response within 12 weeks of completion of treatment. | Achievement of a cure % similar to clinical trials. | Since 2016 |

| Locally advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer | Combined index of compliance with use criteria and health outcomes, based on percentage of patients with RECIST response criteria, after 8–12 weeks of treatment. | Ensure compliance with the PHF use criteria and achieve an adequate clinical response rate. | Since 2019 |

| Haematology-oncology disease | Percentage of patients who have used haematology-oncology drugs in the 30 days prior to death | Reduce patients with curative intent treatment at the end of life. | Since 2019 |

DAS-28: Disease Activity Score; GESIDA: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Study Group of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology; PHF: Pharmacotherapeutic Harmonization Program (PHF for its acronym in Catalan); RECIST: Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

For each indicator, the numerical objective has been established, according to the expected effectiveness, the recommendations of the PHF evaluations and the baseline objective percentage.

The results of the indicators are reported to each hospital quarterly and since 2017 the year-end closing results of all hospitals are published in the Central de Resultats de l’Agència de Qualitat i Avaluació Sanitàries de Catalunya.29

Registry qualityRegarding the increasing use of the data in analyses intended for the management of innovative medicines, it was considered necessary to carry out a registry information reliability check. Thus, in the last semester of 2018, a data validation was carried out by an external company in 7 hospitals, selected according to their degree of complexity and information reporting system to the RPT-HOD, including 9 different disease groups. This validation consisted of checking the data recorded in the RPT-HOD with the medical history data or other sources of information available in the hospital.

613 patients were analysed, with a total of 16,750 observations that were classified as correct (84.69% of those analysed), incorrect (8.56%) or absent (6.75%). However, only 7% of the patients had all their observations correct. The disease group with the most correct observations was that of HIV treatments (94%) and the worst, haematology (51%). The main conclusions were that the registry is reasonably reliable, although the level of follow-up could be improved, especially information on discontinuation and treatment durations. No substantial differences were observed between hospitals or between different registration systems, although the sample was small. As a measure of continuity, it is planned to initiate a quality plan that will guarantee a continuous improvement of governance processes, data and information quality, analysis and use of management data, security and privacy.

Areas for improvement and future challengesDuring these years, the registry has reached an important dimension, not only because of the volume of data it stores, but also because of the high effort and dedication of resources of all the agents involved. Registration requires ensuring adequate training for professionals in the correct registration of cases in time and form, adapting the constant therapeutic developments that are introduced monthly, the management of possible errors that hinder the invoicing of drugs, etc. In many centres the required collection of structured data has been organized in ad hoc repositories, sometimes (but not always) preloaded with data already available in other hospital information sources such as lab test results or diagnostic tests, clinical course, previous treatments, etc., but which are often not integrated in the clinical workstations.

Since its creation and until 2017, hospitals and CatSalut have been focusing their efforts on improving registration as a tool, improving performance, planning and quality, in order to minimize the impact on professionals and obtain robust information which can then be analysed and integrated in decision making. The results have been published only when the information has been considered sufficiently consolidated.

The areas for improvement and future challenges are based on 4 strategic lines:

- -

To improve the usability and quality of the RPT-HOD, reducing information registry interference during the care process. Obtaining most of the information directly from the medical records of each hospital or other internal sources, without the need for ad hoc data entry outside the clinical workstation represents a technological and functional challenge, but it could avoid duplication in the collection of information and, therefore, administrative burdens to professionals and risk of errors in data transcription. Likewise, the quality plan will allow the continuous improvement of the quality and reliability of the information obtained.

- -

Consolidate and expand the systematic analysis of the results, ensuring a return of information to clinicians on the effectiveness of their therapeutic practice jointly and individually, allowing the comparison of expected and obtained results, and sharing experiences between centres in case of heterogeneity. Also, at the beginning of 2018, the RPT-HOD was linked to the Datamart setting, a query tool that facilitates the use and analysis of data and allows the inclusion of information with other CatSalut databases.

- -

Integrate the health results in the PHF evaluation procedure so as to use results in RWD that allow feedback on the use of these drugs and adapt, if necessary, the criteria for use, access and provision of the drugs evaluated, in order to obtain the greatest expected benefit from healthcare investments.

- -

Include standardized methods of measuring results, national and international, for a consistent result comparison,30 encouraging the integration of outcome measures reported by patients (Patient Reported Outcome Measures)31 as a key point in the analysis of value related to the therapeutic novelties in our environment.

In summary, Catalonia has a registry of patients and hospital outpatient drug treatments that has reached a maturity stage after the experience of more than 10 years. It currently covers almost 600 indications of high clinical and economic impact, systematically collects the information on the use of these drugs and, in selected cases, allows to obtain data on health outcomes to support the management of pharmaceutical benefits. Advancing mid-term in the planned strategic lines is a challenge that requires continuity in the participation and dedication of the agents involved, working together in a model of access to therapeutic innovation of greater real value based on evidence and rational use criteria.

Conflict of interestMR, MAP and CP are employees of the Servei Català de la Salut. MQG is employed by a SISCAT public hospital.

The registry exists and has been possible thanks to the countless hours of dedication and effort by health professionals and registration support technicians in the different SISCAT hospitals, as well as thanks to farsightedness of the registry creators, Antoni Gilabert, Josep María Borràs, Josep Alfons Espinàs and Ana Clopés. The daily contribution to the continuous improvement of the registry and to the solution of problems of the technicians of the Management of Information Systems of CatSalut, especially Jaume Clapés, and of the technicians of the Management of Harmonization, Management of Pharmaceutical Benefits and Access to Medicine and the Medicines Territorial Action Division of the CatSalut, which allow the continuity and future development of the project.

Please cite this article as: Roig Izquierdo M, Prat Casanovas MA, Gorgas Torner MQ, Pontes García C. Registro de pacientes y tratamientos de medicamentos hospitalarios en Cataluña: 10 años de datos clínicos. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;154:185–191.