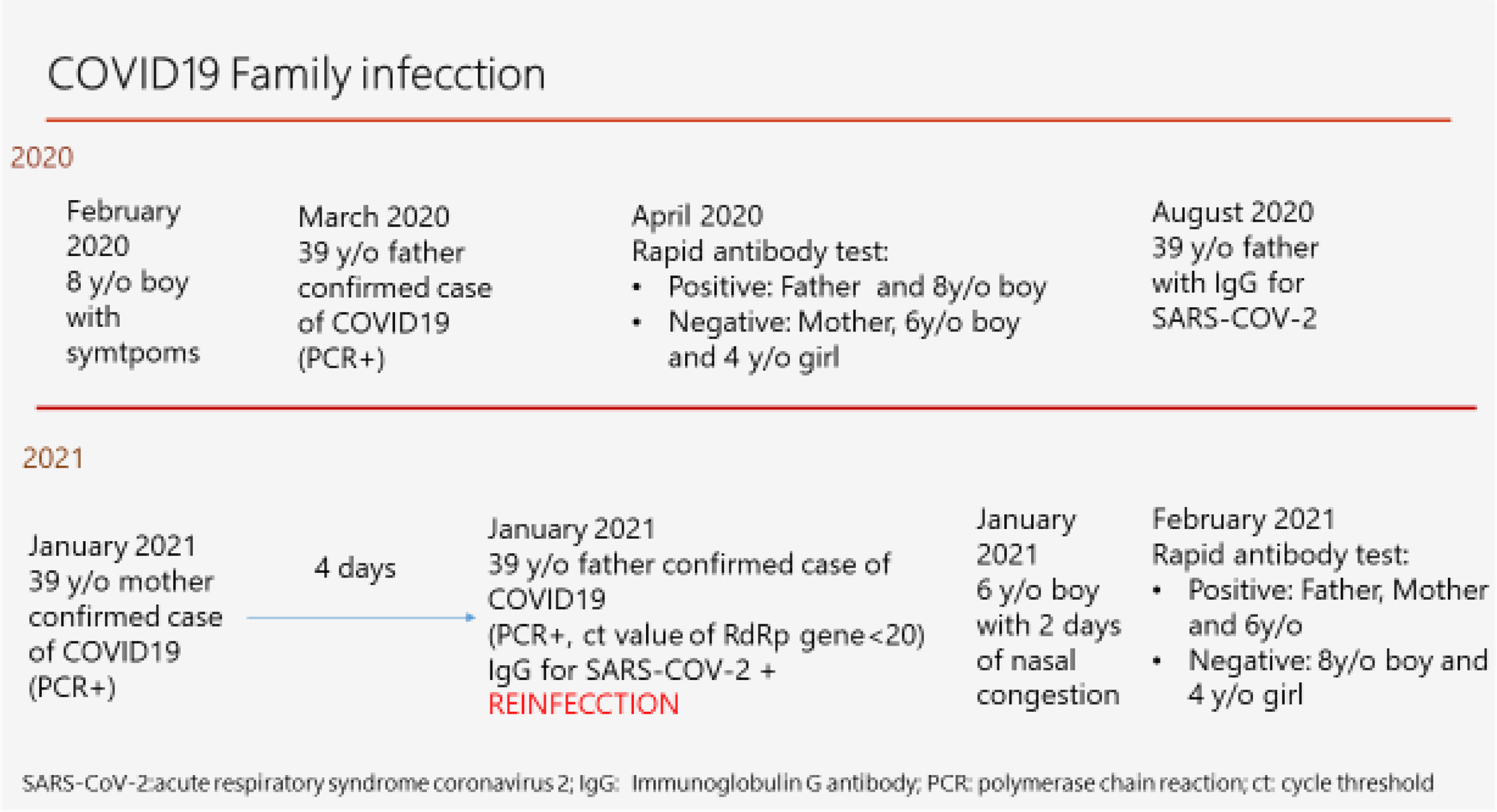

We present a healthy family that live in Spain. Parents are health care workers, the father, Family Physician and the mother, Anaesthetist; they have three children, two boys aged 8 and 6 years and 4 years girl. The suspected first contact that the family had with the acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was mid-February 2020 when the 8 year-old-boy complained for 2 days of intermittent headache, stomach pain and general malaise with no fever or any other symptom. He was treated with occasional acetaminophen; symptoms resolved with a full recovery. No other family member reported any symptoms at the time.

In mid-March 2020 the husband, a 39 year-old Family Physician (FP) was a confirmed case of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by a positive reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test from a oropharyngeal sample and a negative nasopharyngeal RT-PCR test 14 days later. At the time he described 2 days of sore throat, followed by fever up to 38.8°C, general malaise and nasal congestion for 3 days, exertional tachycardia and chest pain for 2 days and loss of smell and taste for about one month. Symptomatic treatment was given with acetaminophen for 5 days as needed. He experienced a full recovery and went back to normal life activities.

By mid-April 2020 the family was tested with rapid antibody tests. The wife, 4-year-girl and 6-year-boy were negative, the FP, the father, was positive with IgM and IgG lines and surprisingly the 8-year-old boy was positive with no IgM line and a strong IgG line. It was suspected that the child's symptoms from February were actually caused by coronavirus, since no other infectious disease was reported, and it coincided with the suspicion that coronavirus was already in circulation in Spain at the time. In August 2020 the blood test was done to FP, Immunoglobulin (Ig)G antibody for SARS-CoV-2 was positive 6.4 (<1.6), no IgM was reported.

Time passed and both physicians kept working and then, in the beginning of January 2021, with the 3rd national and world COVID-19 wave, the healthy 39-year-old Anaesthetist, presented with a mild odynophagia that was followed the next day by general myalgias, feverish sensation with a temperature of 36.4°C, slight general discomfort and nasal congestion. Antigen rapid test was done with a positive result with in the first 2min with a strong positive line. Isolation from the rest of the family members was hard to follow and apparently the husband and the 8-year-old boy were immune. Over the next 2 days, she suffered a slight headache, myalgias and general malaise. She then associated loss of taste and smell and for 2 days she complained of intense triceps and external thigh area muscle pain that resolved in 2 days. At day 7 antigen test was repeated, being still positive, taking longer to give the result and with a less intense line. No fever, cough, dyspnoea or chest pain were ever reported. Symptoms progressively resolved with persistence of loss of smell and taste. At day 11 the antigen test was repeated and found negative. She received symptomatic treatment with acetaminophen which she took occasionally.

Two days later after the wife's initial symptoms, the husband described an uncomfortable night sleep and waking up with a sore throat, that morning the rapid antigen test was negative. The next day a blood test to review SARS-CoV-2 immunity was done revealing positive IgG antibodies 29.30 (<9). The sore throat persisted, with slight general malaise, nasal congestion and some nasal discharge. The following day, day 3, due to symptoms persistence, a second rapid antigen test was done with a light positive result, not with in the first 5min. Tiredness, malaise, nasal congestion and discharge persisted, with no fever or cough over the next days. Symptoms were described as the usual for a cold. Another 2 days passed, rapid antigen test was repeated with a fast strong positive result, that day nasopharyngeal RT-PCR test was done and was found to be POSITIVE, cycle threshold (ct) value of RdRp gene <20, that corresponds with a high viral load. Reinfection was confirmed. A new antigen test was done 3 days later with another slow light positive result. Finally, at the 10th day, rapid antigen test was again done with a negative result. 2 days later, RT-PCR was repeated (a week after the previous one) result still came POSITIVE with a ct of 34. Symptoms progressively resolved within a week, but a funny intermittent smell appeared, with no loss of smell or taste, which resolved in 10 days. RT-PCR was again repeated one week apart, being the test negative. A week later, IgG for SARS-CoV-2 was again reported positive. He was negative for HIV, and showed no biological evidence of immunodeficiency. Genomic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 extracted from the nasopharyngeal PCR swabs from the reinfection revealed 20I/501Y.V1, Britain variant B.1.1.7. This variant was not reported during the first wave in Spain so genetically differences between each infection was concluded, confirming the reinfection by different variants.

On the 7th day of the mother's symptoms and 4th day of the initial symptoms of the father, rapid antigen test was done on the 3 asymptomatic children being all 3 negative. A week later it was repeated, being also negative. The 3 children did not show any symptoms, except for the 6 year-old-boy that complained of nasal congestion for 2 days that did not require any treatment and who did not suffer any loss of energy. 2 days later the previously described antigen test was done on all 3 children.

Two weeks later the rapid total antibody tests were done on all 5 family members: mother and father were positive, the 8 year-old boy and the 4 year-old girl were negative and the 6 year-old-boy was POSITIVE.

All family members experienced a full recovery and progressively reassumed their daily routines (Fig. 1).

In late 2019, a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan City, capital of Hubei in China, were identified to be caused by a novel betacoronavirus, and the disease was named Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). After the genetic sequence of the virus, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses named it severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Coronaviruses are not unknown to humanity, four of these (HCoV-NL63, HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43 and HKU1) currently cause mild common cold symptoms and another two, now extinct, caused epidemics, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002–2003 and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in 2012.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has become the greatest health challenge worldwide of the last century. Clinical presentation of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is highly variable and ranges from asymptomatic to severe pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring intensive care. In this case the children's symptoms were much lighter that the adults and varied among each age group. This milder presentation in children can be explained by the quality and/or quantity difference in the virus cell receptor (ACE2 protein), a greater population of naïve T-cells and some cross protection from antibodies from past infections of other coronavirus, with more incidence during the early years of life.1

Since the beginning of the infections, there has always been a concern about the possibility of reinfections. Coronaviruses are considered stable viruses that limit mutation, errors in RNA sequence, due to a “correcting” enzyme. Data suggest that overall, the short-term risk of reinfection appears low, a study of UK health-care workers showed that reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 is uncommon up to 6 months after the primary infection.

To analyse the available data on reinfection a search in Medline(Pubmed) was done on March 1st 2021 using keywords “COVID19”, “SARS-CoV-2”and “reinfection”. Reinfections are being described related with different viral strains,2,3 so even though the virus is stable it still has the capacity to mutate and avoid the immune system. Sequencing that demonstrates a different strain at the time of presumptive reinfection is necessary to make the distinction. Different viral strains have been described in Europe, South Africa, United Kingdom and Brasil (20E-EU1, B.1.1.7 501YV1 VOC 202012/01, B.1.351 501Y.V2 and B1.1.28)4 revealing the capability of the virus of a natural selection trough bottle necks and founder effects increasing its transmissibility. In most of the cases the second infection was less symptomatic than the initial one, raising the possibility that immunity from an initial infection might attenuate the severity of a reinfection even if it does not prevent it. In this case, the husband's reinfection was much milder that the initial infection, being the second one described as a normal cold. Recent research conducted by Tarke et al.5 indicates that variants are unlikely to escape T cell immunity, in the line that previous infection or vaccination will give protection even if the virus mutates. No Spanish cases were found in the literature, being the first published case in Spain.

Ongoing cases of COVID-19 and the vaccination programmes all over the world will hopefully lead to quicker herd immunity and will stop putting in jeopardy all the health care systems all over the world.

Although the virus is quite stable, it has had access to so many people and has replicated in a virgin human community so the capability of mutations is at its peak.

Reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 is a possibility, this case explains that infections do not provide long-term immunity and that the virus has the ability to mutate and avoid the immune system. We consider that by adding the number of those recovered from the natural infection to those vaccinated, we will have increased the number of humans that have been in contact the virus. The re-exposure to different virus strains will happen, since the mutations capability of the virus has been proven. The immunity generated from the vaccination or natural infection should be able to recognise different virus strains, providing sufficient protection for milder forms of COVID-19, such as the case reported.

Is the virus here to stay? Will it become another common cold virus like HCoV-NL63, HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43 and HKU1? Answers to these questions will be known in the coming months.

External fundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.