Cutaneous manifestations have been included in COVID-19 patients’ clinical spectrum. Our objective was to determine the association between skin lesions in children and SARS-CoV2 infection, analyzing others possible infectious/autoimmune etiologies.

Material and methodsObservational, multicenter, cross-sectional study, about children with skin manifestations from April to May 2020. The diagnosis of SARS-CoV2 was performed by PCR in nasopharyngeal exudate and/or presence of antibodies by serology.

ResultsSixty-two children were included, 9 (14.5%) presented positive antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, with no positive PCR to SARS-Cov-2 in those patients in whom it was made. Patients with positive serology to SARS-CoV-2 presented chilblains and/or vesicular-bullous skin lesions more frequently (66.7% vs. 24.5%, p = 0.019). Generalized, urticarial and maculopapular rash was more common in patients with negative antibodies (37.7 vs. 0%, p = 0.047), others pathogens were isolated in 41.5% of these patients. There were no significant differences in the positivity for autoantibodies between both groups.

ConclusionIn our study, the presence of chilblains-like and/or vesicular lesions were significantly related to SARS-CoV2 previous contact.

Las manifestaciones cutáneas se han incluido en el espectro clínico de los pacientes con COVID-19. Nuestro objetivo fue determinar la asociación entre las lesiones cutáneas observadas en niños durante la primera ola de la pandemia y la infección por SARS-CoV-2, analizando otras posibles etiologías infecciosas o autoinmunes.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional, multicéntrico, de corte transversal, desarrollado en niños con manifestaciones cutáneas desde abril hasta mayo de 2020. La determinación de SARS-CoV-2 se realizó mediante PCR en exudado nasofaríngeo y/o serología.

ResultadosSe seleccionó a 62 niños; 9 (14,5%) presentaron serología positiva para SARS-CoV-2, siendo la PCR negativa en todos los casos en los que se realizó. Los pacientes con serología positiva para SARS-CoV-2 presentaron con más frecuencia lesiones pernióticas y/o vesiculosas (66,7 vs. 24,5%; p = 0,019). El exantema generalizado, urticarial y maculopapuloso fue más habitual en el grupo de pacientes con serología negativa (37,7 vs. 0%; p = 0,047); se aislaron otros patógenos en el 41,5%. No hubo diferencias significativas en cuanto a la positividad de autoanticuerpos entre ambos grupos.

ConclusiónEn nuestro estudio, las lesiones de tipo perniosis o vesiculosas se relacionaron significativamente con el contacto previo con SARS-CoV-2.

Since the emergence in December 2019 of the new coronavirus causing acute respiratory distress syndrome type 2 (SARS-CoV-2), numerous articles have described its clinical spectrum in children, including the occurrence of skin lesions.

Studies conducted during the first wave of the pandemic showed that up to 20.4% of patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection had cutaneous manifestations,1–3 of which erythematous rash was the most commonly described. Subsequently, other studies classified the types of rash attributable to the disease and related them to the stages and severity of the infection.

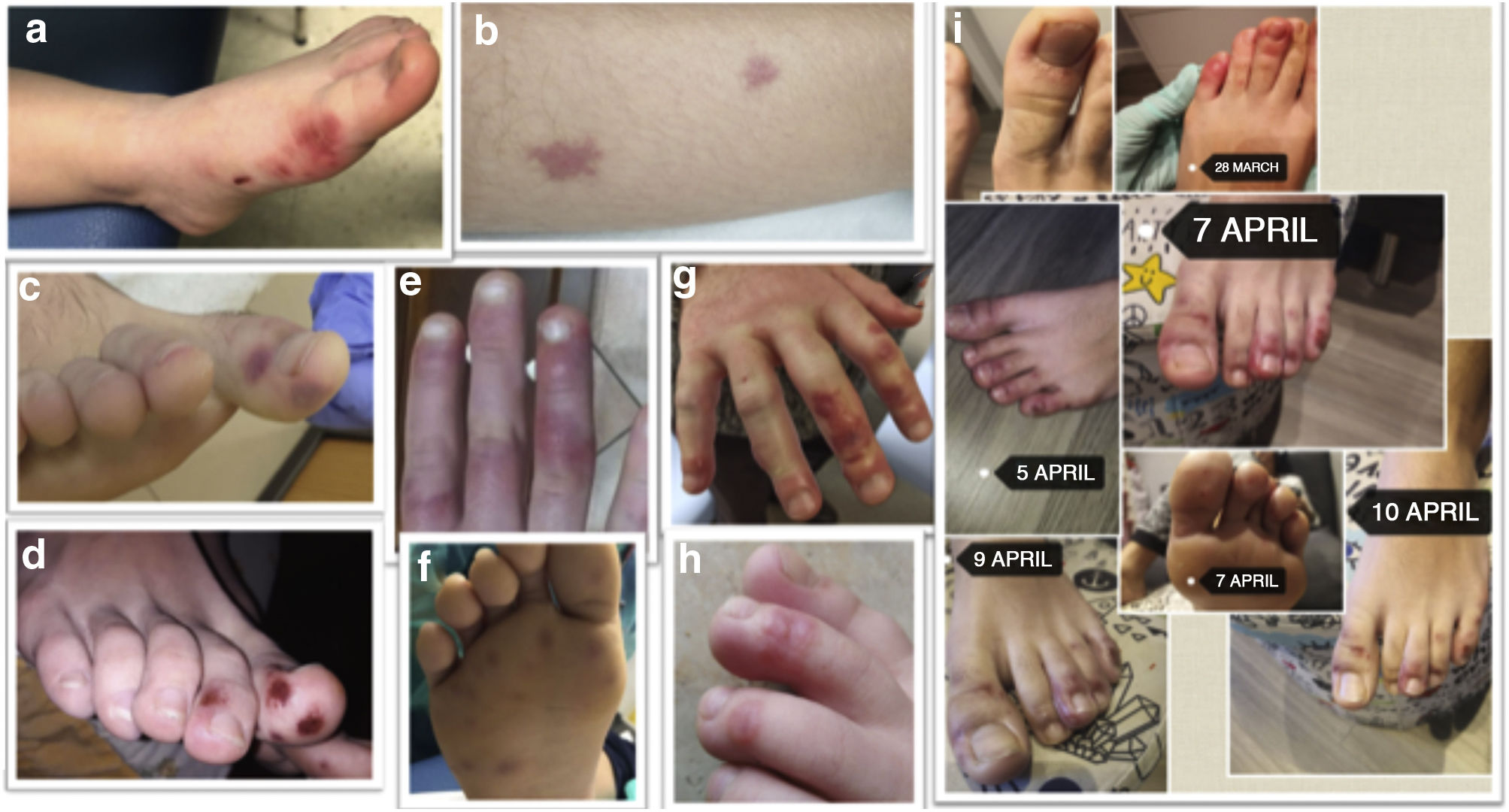

Paediatric series repeatedly describe the occurrence of acral erythematous-violaceous lesions, similar to chilblain, especially in late stages, in oligosymptomatic o subclinical patients, with spontaneous remission.4–6 In adults, necrotic/ischemic lesions have been related to prothrombotic states triggered by the virus, and this phenomenon has not been studied in children.

The main objective of our study was to describe the skin manifestations in children during the first wave of the pandemic, trying to identify the infectious etiological agents involved, especially their association with SARS-CoV-2. In addition, we aimed to detect whether SARS-CoV-2 contact could trigger autoimmune phenomena by analysing the role of anti-phospholipid antibodies.

Material and methodsObservational, multicenter, cross-sectional study. Two tertiary-level hospitals and one regional hospital in southern Spain (Granada and Malaga) participated. The patients were selected from Primary Care or the Emergency Department.

Children under the age of 16 who presented with skin lesions between April and May 2020 were included. Those patients with chronic disease that could affect the skin were excluded.

Epidemiological, clinical, laboratory and treatment data were collected. The serological determination of SARS-CoV-2 was done by rapid test (solid phase immunochromatographic assay for differential detection of IgM/IgG type Lambra®) or indirect chemiluminescence (CLIA-Virclia®). A nasopharyngeal swab PCR for multiple viruses, bacteria, and SARS-CoV-2 (Roche® 6800) was used in patients with a clinical course of less than 7 days. The study was completed by plasma autoantibody, immunoglobulin and complement determination.

We defined as a probable cause of skin lesions a positive nasopharyngeal swab PCR or serum IgM detection of any microorganism usually associated with skin lesions. A recent SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined as positive PCR or IgM detection (by immunochromatography or CLIA), and positive IgG detection as past infection. In the case of positive IgM and IgG, a recent infection was considered if the nasopharyngeal swab PCR was positive.

Data analysis was performed using SSPS v. 22 software. To contrast hypotheses, the χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests were used in the case of qualitative variables, and the Student’s t test and Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative variables. A p < 0.1 was established as the level of significance, given the small sample size.

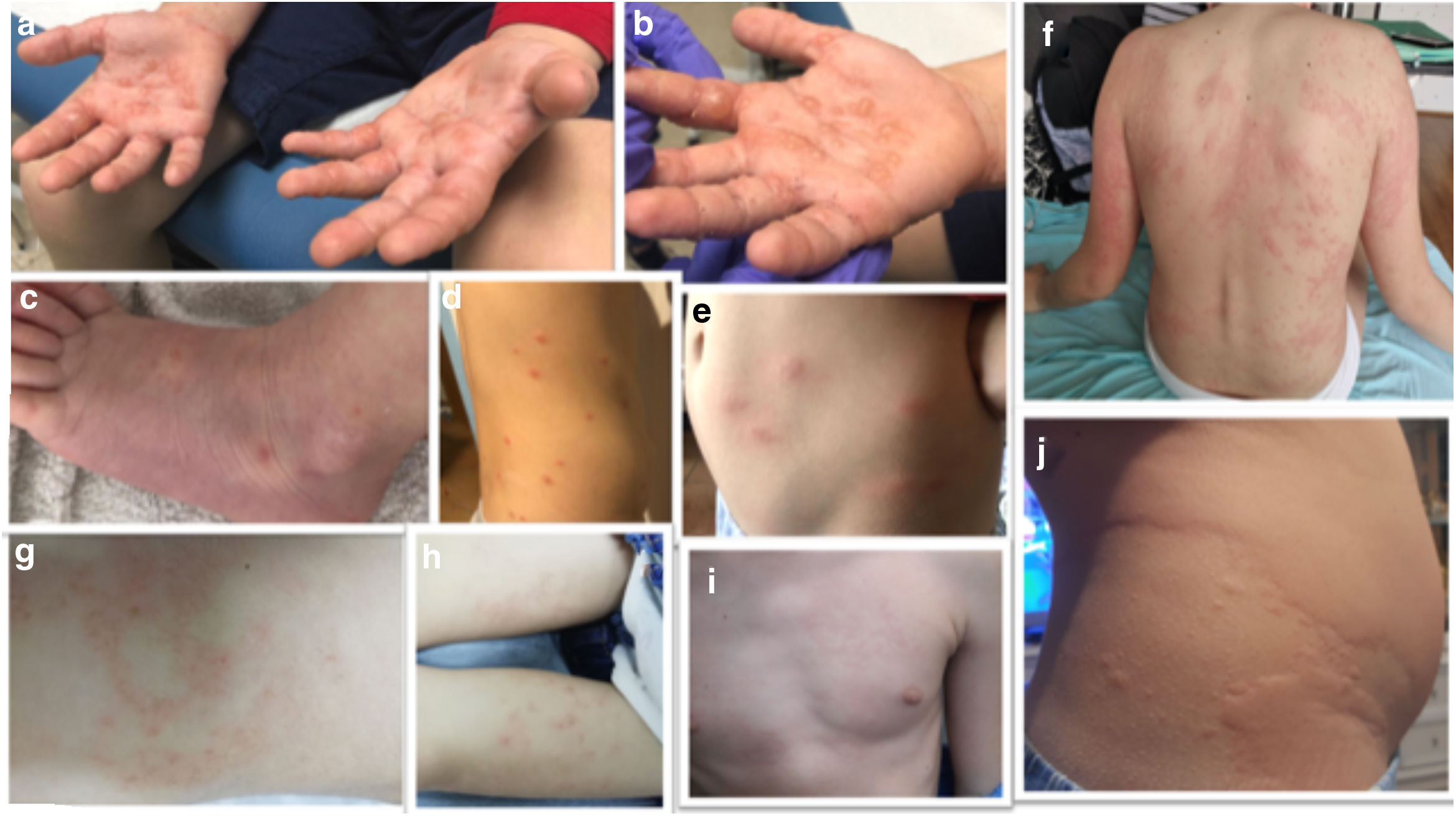

Results62 patients were selected. The median age was 10 years (IQR 5.4–12.6) and 59.7% were male. The skin lesions were 32.3% maculopapular; 22.6% chilblain-like; 16.1% hive-like; 8.1% vesicular and 8.1% livedoid-like/necrotic. 26% had other types of lesions, mainly ecchymotic. More than half were located in acral areas (56.5%), predominantly on the feet (45.2%) and 32.3% were generalised. The different types of lesions are discussed in Figs. 1 and 2.

(a–b) Vesicular lesions (positive serology for Mycoplasma). (c) Vesicular lesions (without microbiological isolation). (d–e) Maculopapular rashes (positive serology for Mycoplasma). (f–i) Maculopapular rashes (without microbiological isolation). (j) Hive-like rash (positive serology for Mycoplasma).

PCRs for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal swabs from 36 patients were all negative. All underwent serology, 61 CLIA and 43 immunochromatographic assay, and 9 patients with evidence of contact with SARS CoV-2 (14.5%) were detected by either method, 7 with negative IgM and positive IgG, one with both positive and another one with positive IgM. The population prevalence estimate was 5.74%–25.26% (95% CI).

Of the patients with positive serology, only one required hospitalization for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C).

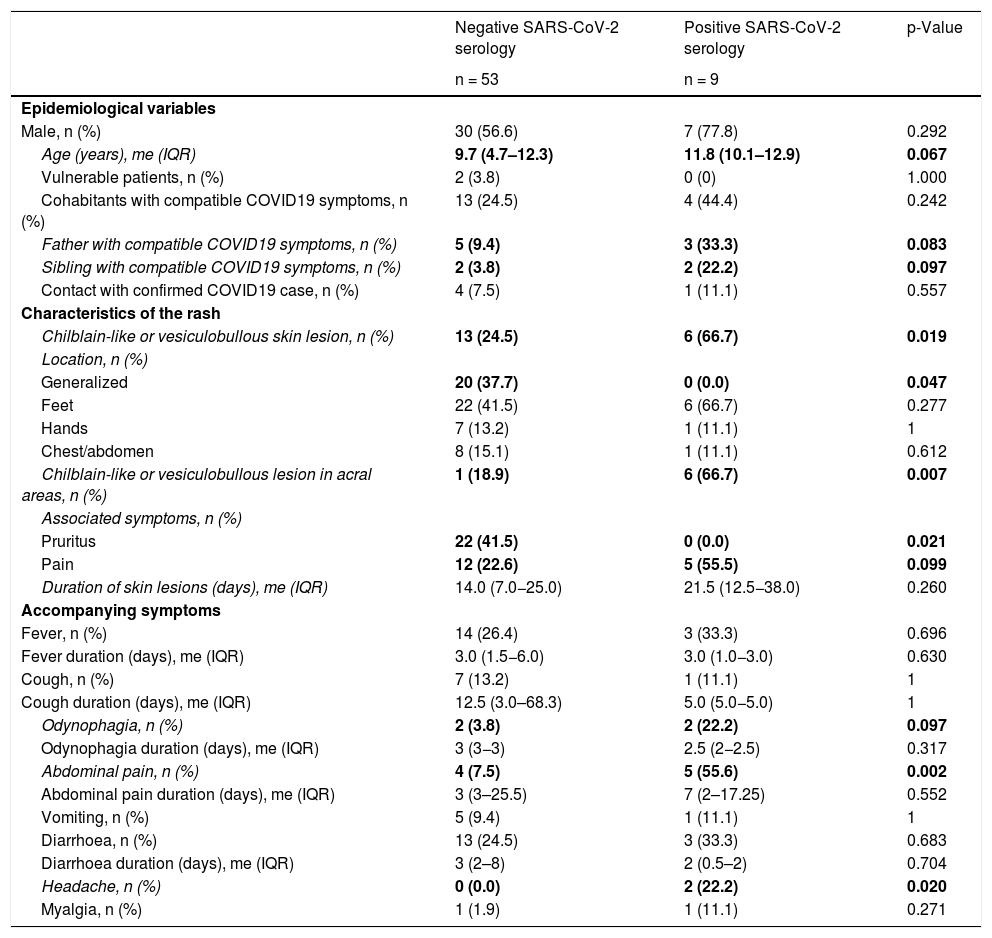

The characteristics of patients with evidence of previous SARS-CoV-2 contact and those without were compared (Table 1).

Epidemiological and clinical differences of the comparative groups.

| Negative SARS-CoV-2 serology | Positive SARS-CoV-2 serology | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 53 | n = 9 | ||

| Epidemiological variables | |||

| Male, n (%) | 30 (56.6) | 7 (77.8) | 0.292 |

| Age (years), me (IQR) | 9.7 (4.7–12.3) | 11.8 (10.1–12.9) | 0.067 |

| Vulnerable patients, n (%) | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Cohabitants with compatible COVID19 symptoms, n (%) | 13 (24.5) | 4 (44.4) | 0.242 |

| Father with compatible COVID19 symptoms, n (%) | 5 (9.4) | 3 (33.3) | 0.083 |

| Sibling with compatible COVID19 symptoms, n (%) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (22.2) | 0.097 |

| Contact with confirmed COVID19 case, n (%) | 4 (7.5) | 1 (11.1) | 0.557 |

| Characteristics of the rash | |||

| Chilblain-like or vesiculobullous skin lesion, n (%) | 13 (24.5) | 6 (66.7) | 0.019 |

| Location, n (%) | |||

| Generalized | 20 (37.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.047 |

| Feet | 22 (41.5) | 6 (66.7) | 0.277 |

| Hands | 7 (13.2) | 1 (11.1) | 1 |

| Chest/abdomen | 8 (15.1) | 1 (11.1) | 0.612 |

| Chilblain-like or vesiculobullous lesion in acral areas, n (%) | 1 (18.9) | 6 (66.7) | 0.007 |

| Associated symptoms, n (%) | |||

| Pruritus | 22 (41.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.021 |

| Pain | 12 (22.6) | 5 (55.5) | 0.099 |

| Duration of skin lesions (days), me (IQR) | 14.0 (7.0−25.0) | 21.5 (12.5−38.0) | 0.260 |

| Accompanying symptoms | |||

| Fever, n (%) | 14 (26.4) | 3 (33.3) | 0.696 |

| Fever duration (days), me (IQR) | 3.0 (1.5−6.0) | 3.0 (1.0−3.0) | 0.630 |

| Cough, n (%) | 7 (13.2) | 1 (11.1) | 1 |

| Cough duration (days), me (IQR) | 12.5 (3.0–68.3) | 5.0 (5.0−5.0) | 1 |

| Odynophagia, n (%) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (22.2) | 0.097 |

| Odynophagia duration (days), me (IQR) | 3 (3−3) | 2.5 (2−2.5) | 0.317 |

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | 4 (7.5) | 5 (55.6) | 0.002 |

| Abdominal pain duration (days), me (IQR) | 3 (3–25.5) | 7 (2–17.25) | 0.552 |

| Vomiting, n (%) | 5 (9.4) | 1 (11.1) | 1 |

| Diarrhoea, n (%) | 13 (24.5) | 3 (33.3) | 0.683 |

| Diarrhoea duration (days), me (IQR) | 3 (2–8) | 2 (0.5–2) | 0.704 |

| Headache, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | 0.020 |

| Myalgia, n (%) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (11.1) | 0.271 |

In bold, variables achieving a significant difference.

Differences were observed in the type of rash between both groups (Table 1). Patients with previous SARS-CoV-2 contact presented more chilblain-like or vesicular lesions (66.7 vs. 24.5%; p = 0.019). If said rash was located in acral parts, the differences became even more evident (66.7 vs. 18.9%; p = 0.007). The patient with MIS-C was the only one with positive serology for SARS-CoV-2 and maculopapular lesions on the chest and abdomen.

Generalized hive-like and maculopapular rashes were more common in patients without evidence of SARS-CoV-2 contact (37.7 vs. 0%; p = 0.047).

There was a single case of hypoxemia and respiratory distress, without prior SARS-CoV-2 contact, and 2 cases of respiratory distress without hypoxemia, one in the patient with MIS-C and another in the group without evidence of contact with SARS- CoV-2.

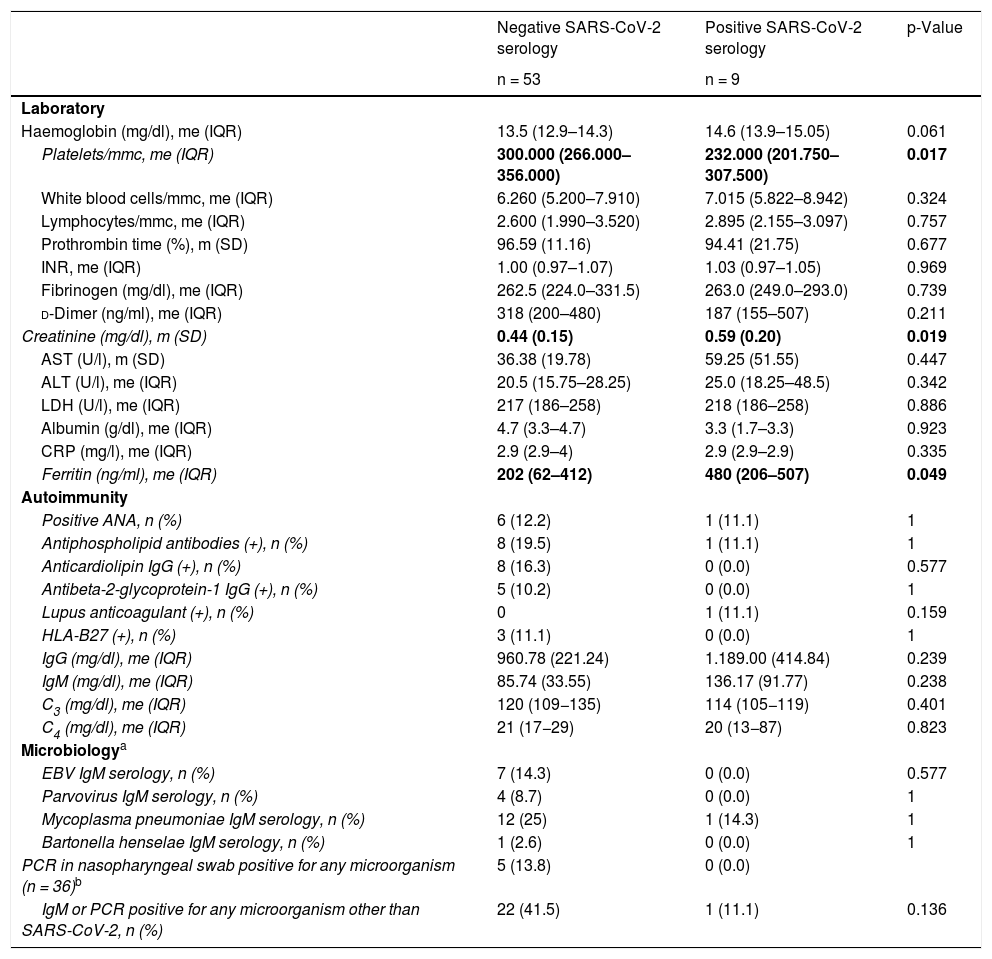

Regarding the laboratory tests (Table 2), only the serum ferritin values were significantly higher in the group with SARS-CoV-2 contact (202 ng/ml [62–412] vs. 480 ng/ml [206–507]; p = 0.049). No significant differences were detected in the total ANA positive rate and ANCAs were negative in all cases. Regarding antiphospholipid antibodies, 8 cases were detected with positive anticardiolipin antibodies in IgG, 5 of them also positive for anti-b2GP1 IgG, all in the group without SARS-CoV-2 contact. A laboratory control was carried out 3 months later in 4 of them, remaining positive, although with decreased titers. Positive lupus anticoagulant was observed in the patient with MIS-C. No patient had a personal or family history of ischemic conditions or developed them later.

Comparative laboratory data (complete blood count, biochemistry, autoimmunity, and microbiology).

| Negative SARS-CoV-2 serology | Positive SARS-CoV-2 serology | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 53 | n = 9 | ||

| Laboratory | |||

| Haemoglobin (mg/dl), me (IQR) | 13.5 (12.9–14.3) | 14.6 (13.9–15.05) | 0.061 |

| Platelets/mmc, me (IQR) | 300.000 (266.000–356.000) | 232.000 (201.750–307.500) | 0.017 |

| White blood cells/mmc, me (IQR) | 6.260 (5.200–7.910) | 7.015 (5.822–8.942) | 0.324 |

| Lymphocytes/mmc, me (IQR) | 2.600 (1.990–3.520) | 2.895 (2.155–3.097) | 0.757 |

| Prothrombin time (%), m (SD) | 96.59 (11.16) | 94.41 (21.75) | 0.677 |

| INR, me (IQR) | 1.00 (0.97–1.07) | 1.03 (0.97–1.05) | 0.969 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl), me (IQR) | 262.5 (224.0–331.5) | 263.0 (249.0–293.0) | 0.739 |

| d-Dimer (ng/ml), me (IQR) | 318 (200–480) | 187 (155–507) | 0.211 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl), m (SD) | 0.44 (0.15) | 0.59 (0.20) | 0.019 |

| AST (U/l), m (SD) | 36.38 (19.78) | 59.25 (51.55) | 0.447 |

| ALT (U/l), me (IQR) | 20.5 (15.75–28.25) | 25.0 (18.25–48.5) | 0.342 |

| LDH (U/l), me (IQR) | 217 (186–258) | 218 (186–258) | 0.886 |

| Albumin (g/dl), me (IQR) | 4.7 (3.3–4.7) | 3.3 (1.7–3.3) | 0.923 |

| CRP (mg/l), me (IQR) | 2.9 (2.9–4) | 2.9 (2.9–2.9) | 0.335 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml), me (IQR) | 202 (62–412) | 480 (206–507) | 0.049 |

| Autoimmunity | |||

| Positive ANA, n (%) | 6 (12.2) | 1 (11.1) | 1 |

| Antiphospholipid antibodies (+), n (%) | 8 (19.5) | 1 (11.1) | 1 |

| Anticardiolipin IgG (+), n (%) | 8 (16.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.577 |

| Antibeta-2-glycoprotein-1 IgG (+), n (%) | 5 (10.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| Lupus anticoagulant (+), n (%) | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 0.159 |

| HLA-B27 (+), n (%) | 3 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| IgG (mg/dl), me (IQR) | 960.78 (221.24) | 1.189.00 (414.84) | 0.239 |

| IgM (mg/dl), me (IQR) | 85.74 (33.55) | 136.17 (91.77) | 0.238 |

| C3 (mg/dl), me (IQR) | 120 (109−135) | 114 (105−119) | 0.401 |

| C4 (mg/dl), me (IQR) | 21 (17−29) | 20 (13−87) | 0.823 |

| Microbiologya | |||

| EBV IgM serology, n (%) | 7 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.577 |

| Parvovirus IgM serology, n (%) | 4 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM serology, n (%) | 12 (25) | 1 (14.3) | 1 |

| Bartonella henselae IgM serology, n (%) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| PCR in nasopharyngeal swab positive for any microorganism (n = 36)b | 5 (13.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| IgM or PCR positive for any microorganism other than SARS-CoV-2, n (%) | 22 (41.5) | 1 (11.1) | 0.136 |

In bold, variables achieving a significant difference.

The percentage of patients with positive nasopharyngeal swab IgM or PCR for any of the tested microorganisms was higher in the group with negative serology for SARS-CoV-2, without statistical significance (41.5 vs. 11.1%; p = 0.136).

At recruitment, 7 patients (11.3%) were on topical treatment, mainly corticosteroids, and 10 were receiving systemic treatment, especially antihistamines. After our evaluation, topical corticosteroids were indicated in 4 cases, one of them with previous SARS-CoV-2 contact, and oral antihistamines in 10; with better response being observed in patients who had not had SARS-CoV-2 contact (complete response in 87.5 vs. 0.0%; p = 0.067).

DiscussionDespite multiple studies reporting rashes associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection during the first wave, due to the burden of care and the scarcity of diagnostic tests at the time, few studies adequately documented the relationship. Most only performed PCR or serology on a percentage of the patients included,5,6 while others did not specify the microbiological technique used.2

In our series, a serological study was performed in all patients. The relationship of this type of lesion with late stages of the disease2,5,6 makes serology a useful test in diagnosis. In addition, nasopharyngeal swab PCR was performed for SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens to those patients with a clinical course of less than 7 days, which is why we consider that this study provides more aetiological information.

In our study, 66.7% of the patients with chilblain-like or vesicular lesions in acral areas had positive IgG antibodies for SARS-CoV-2, with statistically significant differences compared to the group with negative serology. These types of lesions were described in different countries during the first wave. As they are often associated with cold temperatures, their presence during spring alerted the scientific community. Some publications could not confirm SARS-CoV-2 infection7 and associated them with the sedentary lifestyle experienced during lockdown. However, its coincidence with the peak of the pandemic and the notification of numerous cases in the same period led other authors to support its relationship with the infection. In the multicenter study carried out by Galván-Casas et al.,2 of the 375 patients included, 19% had chilblain-like lesions and infection was confirmed in 41%, who generally developed mild symptoms and in late stages.

Other skin manifestations have been described in relation to COVID-19. Two multicenter studies with a mostly adult population2,3 showed that maculopapular rash was the most commonly observed manifestation, related to initial stages and coinciding with the onset of respiratory symptoms. Isolated cases of macular, hive-like, vesicular, and erythema multiforme rashes have been reported in children whose SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal PCR was positive.8,9 In our study, hive-like and maculopapular rashes were more common in patients without prior SARS-CoV-2 contact. Differential diagnosis with other aetiologies is essential in this type of lesion, as shown by our results, in which 41% of the patients without evidence of previous SARS-CoV-2 contact had infection by some other microorganism, especially EBV or mycoplasma.

Furthermore, our study found other differences between the skin lesions of both groups. Lesions occurring in the serology-positive group were more painful and more often associated with headache and abdominal pain. However, the clinical response to oral antihistamines was worse. These data support the possibility that COVID-19 plays a role in the genesis of some of these rashes.

Regarding the lesion development mechanism, the direct action of the virus on the skin could play a role in the onset of the lesions. Different studies have shown that the ACE-2 receptor is present in the endothelial cells of the blood vessels located in the basal layer of the epidermis10; the virus has been detected by electron microscopy and PCR techniques in skin biopsies.8

Other authors defend that they are the result of the patient’s immune response and that thrombotic phenomena and vasculitis occur in those with more severe symptoms.3 Among adult patients with COVID-19 who have developed thrombotic phenomena, it has been postulated that the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies may account, among other factors, for the development of coagulopathy. Of the patients with previous contact with SARS-CoV-2 in our study, only the patient with MIS-C was a carrier of these antibodies, with no associated ischemic or thrombotic phenomena.

Our study has some limitations. The impossibility of performing nasopharyngeal PCR detection for SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens in all patients, together with the determination of a single serological sample, may have underestimated the percentage of patients with COVID-19 in our sample. Therefore, more studies would be necessary to corroborate our results.

In conclusion, skin manifestations, especially chilblain-like and vesicular manifestations, could be part of the clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, in the case of generalized hive-like and maculopapular rashes, a differential diagnosis with other infectious diseases typical of childhood should be performed.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We wish to thank all Primary Care paediatricians for their collaboration in the study and their work in the selection and referral of patients, as well as the nursing team that collaborated in sample collection.

Please cite this article as: Carazo Gallego B, Martín Pedraz L, Galindo Zavala R, Rivera Cuello M, Mediavilla Gradolph C, Núñez Cuadros E. Lesiones cutáneas en niños durante la primera ola de la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2. Med Clin (Barc). 2021;157:33–37.