The coronavirus-2 disease 2019 (COVID-19) presents a particularly high infection rate and, by 1st May 2020, a total of 3,269,667 cases were confirmed worldwide.1,2 Social distancing measurements approved by national governments have been demonstrated as the most efficient way for controlling the spread of the disease, though severe socio-economic impact is derived from the limitation of non-essential activities. Medical attention at all levels is not an exception with a variable interpretation of what “essential health-care” is in each geopolitical context. For the first time in our era, we health-care professionals are facing the feeling of having abandoned some of our duties to focus in only one. At the same time, we are all aware of the great anxiety that the population is suffering while we are unable to comfort them, which is one of our main missions. Not only that, but from our particular perspective as cardiologists, there are also all the potential cardiovascular effects of the pandemic that we are not preventing.3 Such frustration has forced both, physicians and patients, to seek for alternative ways to communicate. Telephonic attention to our patients was slowly settled, but this tool has not been widely available. As a consequence, there was a movement in the social network Twitter where physicians offered their free advice to whoever needed it. I joined that initiative in March 15th 2020 (XXXX11). Not being one of the most popular physicians (or even cardiologists) in this network – with only little above 1200 followers – I was surprised on how quickly the tweet spread. One month and a half after its publication, more than 22,600 people watched it and a total of 1077 people worldwide directly requested my help. The aim of this manuscript is to report the results and analyze the potential impact of this approach in the health-care system logistics from now on.

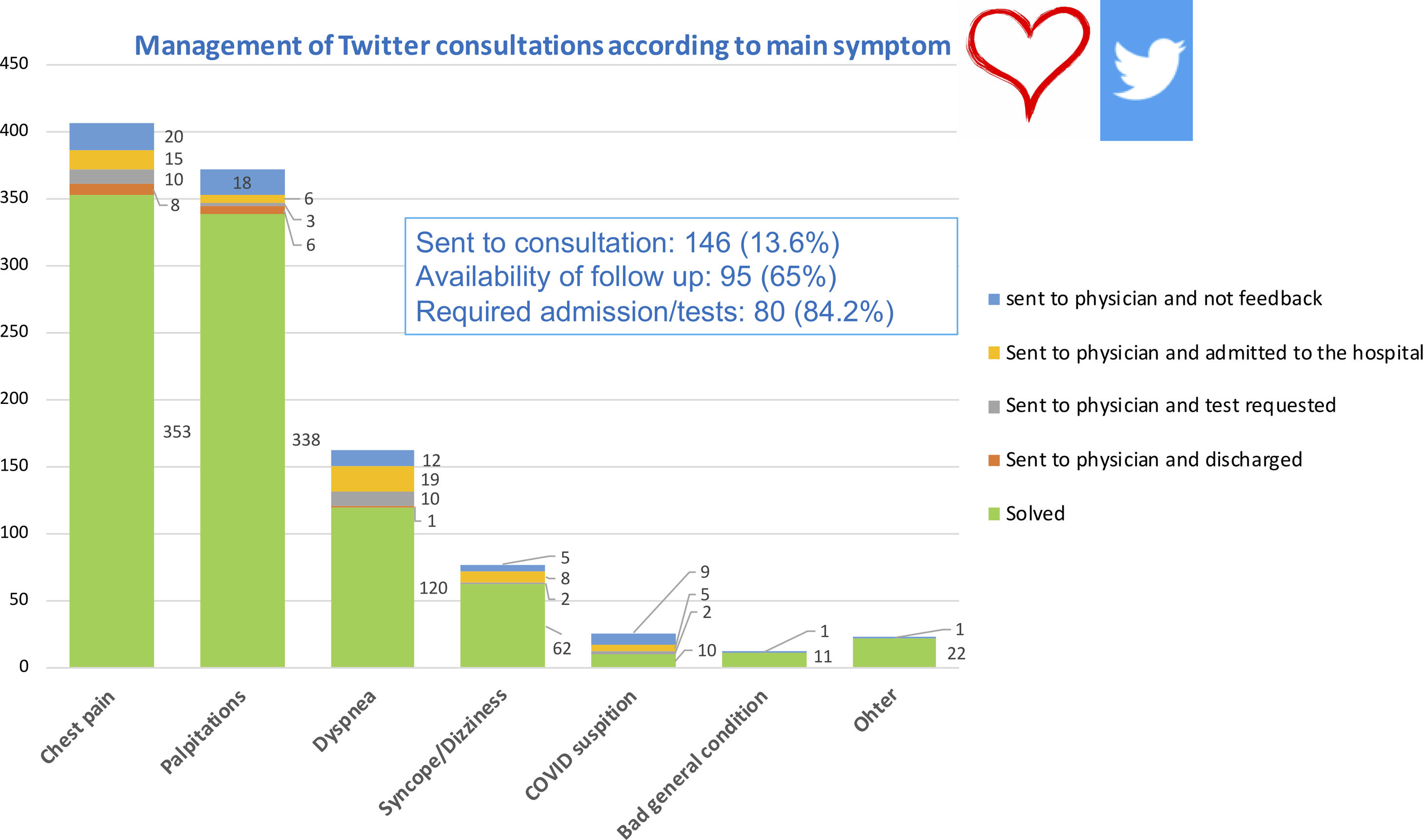

Users that requested attention were mainly from Spain (556, 51.6%) and Latin America or other regions (521, 48.4%), though this was not always identifiable. As seen in Fig. 1, the main symptom was variable but chest pain and palpitations accounted for 72% of the global number of messages. The larger proportion of the cases (86.3%) could be solved via Twitter through a short anamnesis given the lack of risk criteria according to the Guidelines.3 In these cases, recommendation to attend their primary care professional once social distancing measurements were relaxed was given. In this group, none of the patients with an available follow up required emergent attention. An immediate visit to an emergency department or a primary care physician was recommended in a total of 145 cases (13.5%). In 65% of these cases follow up was obtained with 84.2% of the patients requiring further tests or admitted to the hospital and only 9.6% discharged after this initial medical contact.

Our main conclusion from this experience is that the initiative was useful for the society. We do not ignore its limitations, including the unknown rate of misdiagnosis due to lack of appropriate evaluation, and the lack of a legal framework to protect both professionals and patients. These crucial elements were disregarded only due to the global health-care crisis but this provided an unprecedented opportunity to perform a preliminary evaluation of the ability of digital platforms for providing health assessment globally. National health-care systems have demonstrated to be limited to confront global health crisis in the 21st century. It is well-known that health-care access is unequal worldwide; however, the ability to provide a basic triage is easier and cheaper than ever. Just imagine how we could have anticipated the course of events if people in Wuhan had massively requested attention through such kind of platform. Perhaps we can get something good out of the pandemic and the sentence “creating opportunities in times of crisis” is more than a catch phrase.

Financial disclosuresNone to declare.