Quality indicators (QIs) are essential for adequate control of the health care management process, recognizing areas of improvement and providing solutions. We aimed to evaluate the Integrated Breast Cancer (BC) Care Process QIs.

MethodsWe studied 487 consecutive BC cases diagnosed from November 1st, 2013, to November 30th, 2019, in a Spanish healthcare area, and we estimated the associated QIs.

ResultsFour indicators did not meet the standards and were analysed based on related sociodemographic and clinical variables. The surgical delay after a multidisciplinary team discussion (mean 64%, IQR 59.6–68.5) was lower in elder people (p=0.027), and early histological grades (p=0.019) and stages (p=0.008). The adjuvant treatment delay (mean 55.7%, IQR 51.1–60.3) was lower in advance stages (p=0.002) and when there was no reoperation (p=0.001). The surgical delay after inclusion (mean 83.2%, IQR 79.3–87.2) was lower in early histological grades (p=0.048). The immediate reconstruction (mean 42.3%, IQR 34.0–50.5) reached 72.3% in young women compared to 11.8% in older than 70 years (p=0.001) and it was higher in early stages (45.3% vs 36.2%; p=0.049).

ConclusionThe study of QIs evaluated their compliance and analysed the variables influencing them to propose improvement measures. Not all the indicators were equally valuable. Some depended on the available resources, and others on the mix of patients or complementary treatments. It would be essential to identify the specific target populations to estimate the indicators or provide standards stratified by the related variables.

Los indicadores de calidad (IC) son esenciales para el adecuado control del proceso asistencial en el sistema sanitario, permitiendo el reconocimiento de áreas de mejora y proporcionando soluciones. Nuestro propósito ha sido evaluar los IC en el proceso asistencial integrado cáncer de mama (CM).

MétodosSe estudiaron 487 casos consecutivos de CM diagnosticados desde noviembre de 2013 hasta 2019 en un área sanitaria de España y se estimaron los IC asociados.

ResultadosCuatro indicadores no cumplieron los estándares de calidad y fueron analizados en función de las variables sociodemográficas posiblemente relacionadas. El retraso quirúrgico tras el comité multidisciplinar (media 64%, rango intercuartílico [IQR] 59,6-68,5) fue menor en pacientes más mayores (p=0,027), y en grados histológicos (p=0,019) y estadios (p=0,008) más tempranos. El retraso en el tratamiento adyuvante (media 55,7%, IQR 51,1-60,3) fue menor en estadios más avanzados (p=0,002) y cuando no hubo necesidad de rescisión (p=0,001). El retraso quirúrgico tras la inclusión en lista de espera (media 83,2%, IQR 79,3-87,2) fue menor en grados histológicos más tempranos (p=0,048). La reconstrucción inmediata (media 42,3%, IQR 34,0-50,5) se realizó en un 72,3% de las mujeres jóvenes comparado con tan solo un 11,8% de las mayores de 70 años (p=0,001) y fue mayor en estadios tempranos (45,3% vs. 36,2%; p=0,049).

ConclusiónEl estudio de los IC evaluó su cumplimiento y analizó las variables que los influencian para proponer medidas que los mejoren. No todos los indicadores pudieron evaluarse de igual forma. Algunos dependieron de los recursos disponibles, otros del tipo de paciente y otros de los tratamientos complementarios. Sería necesario identificar las poblaciones diana para estimar los IC más adecuados o proporcionar estándares estratificados por las variables relacionadas.

Breast cancer (BC) is women's most common type of cancer. The annual incidence is 33,000 cases in Spain.1 Most are diagnosed between 45 and 80 years old, with a maximum incidence between 45 and 70 years old.2 The main purpose of the treatment is to increase disease-free survival and overall survival,2 which has notably improved in recent decades.3 This trend can be attributed to early diagnosis in symptomatic patients and screening programs and the individual application of new treatments based on the cancer characteristics.2,4,5 At the same time, all these advances and the development of oncoplastic techniques have reduced the surgical treatment's aggressiveness and improved aesthetic and functional results.6 Consequently, the BC treatment is more satisfactory but intricate because the ideal approach requires a high degree of individualisation, scientific-technical updating, multidisciplinary coordination and continuous review of results.7,8

The greater therapeutic complexity requires improving the quality of cancer diagnosis and treatment.2 Information systems must be incorporated for the surveillance and continuous evaluation of results. They would allow self-evaluation and detection of opportunities for improvement.9 To harmonise the evaluation of BC management quality, various QIs have been proposed, but there is still no consensus.10–12 Each Autonomous Community has developed a Breast Cancer Integrated Health Care Process in Spain. In Andalusia, this Integrated Health Care Process is defined as the “set of preventive, diagnostic, therapeutic, follow-up and care activities, used at the comprehensive management of people … with increased risk for BC, …” and includes a series of QIs for the continuous improvement.2 Their estimation requires the maintenance of a sociodemographic, clinical and healthcare database. There are three kinds of QIs: indicators of structure (measures all the sources used during the procurement of services), process (assesses the procedures done during patient care), and outcome (analyses the results of patient care).13 It is essential to study the variables that could influence the QIs, especially in indicators of outcomes, where changes in these factors could be done. However, this is not usual for process indicators where everyone should have access to the best evidence-based practices, so modifications would be more rigid.14

To our knowledge, there are no studies in Spain that assess the impact of the analysis of QIs. Our work aims to evaluate the performance of the BC QIs to improve the Integrated Health Care Process and identify areas for improvement.

Methods and materialsA prospective observational study was done on a series of consecutive BC cases diagnosed and treated without sex or age exclusions from November 1st, 2013 to November 30th, 2019, in a Regional Hospital in a southern Spanish health care area. Patients diagnosed with benign breast pathology were excluded.

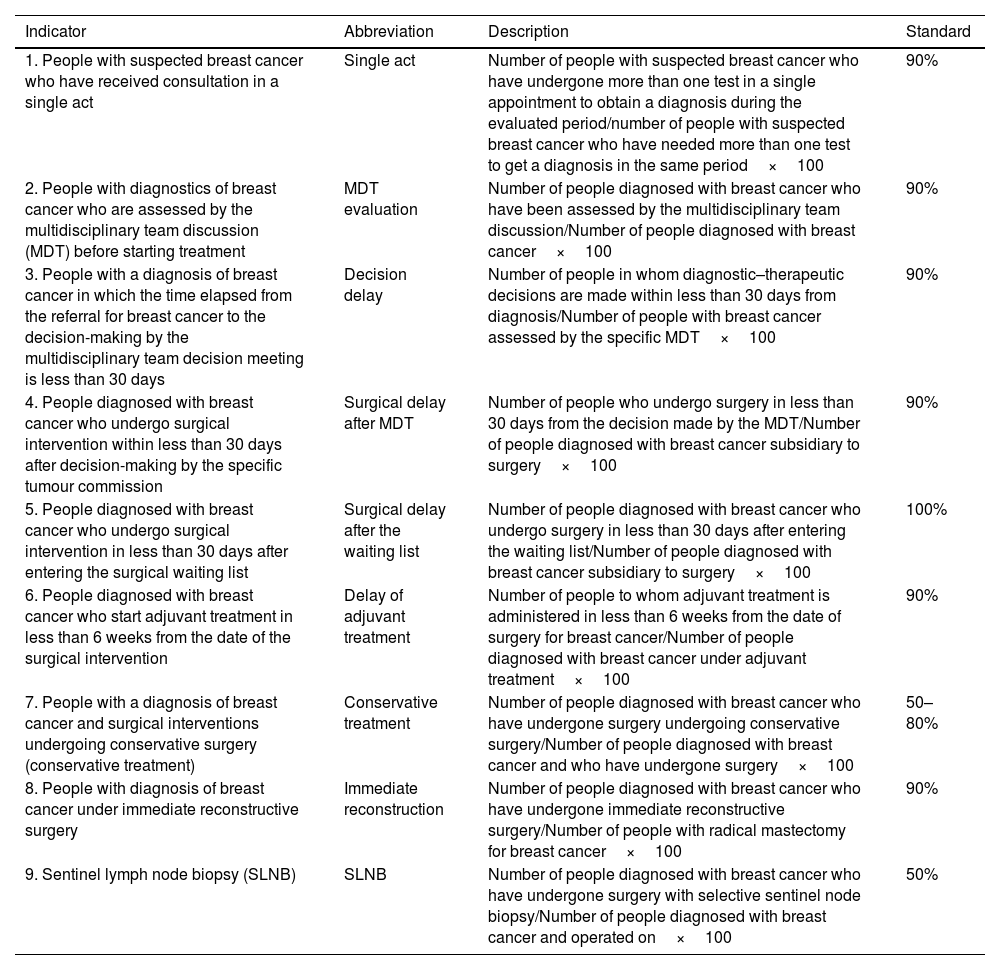

Quality indicatorsA set of nine QIs and their standards of quality care were collected from the Andalusian Breast Cancer Integrated Health Care Process,2 where the study has taken place. This quality document was based on the EUSOMA position paper,11 which fixed the validity criteria. Table 1 shows the specified formula and the QIs fulfilment.10

List of the Integrated Breast Cancer Care Process selected indicators supplemented by their description and standard.

| Indicator | Abbreviation | Description | Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. People with suspected breast cancer who have received consultation in a single act | Single act | Number of people with suspected breast cancer who have undergone more than one test in a single appointment to obtain a diagnosis during the evaluated period/number of people with suspected breast cancer who have needed more than one test to get a diagnosis in the same period×100 | 90% |

| 2. People with diagnostics of breast cancer who are assessed by the multidisciplinary team discussion (MDT) before starting treatment | MDT evaluation | Number of people diagnosed with breast cancer who have been assessed by the multidisciplinary team discussion/Number of people diagnosed with breast cancer×100 | 90% |

| 3. People with a diagnosis of breast cancer in which the time elapsed from the referral for breast cancer to the decision-making by the multidisciplinary team decision meeting is less than 30 days | Decision delay | Number of people in whom diagnostic–therapeutic decisions are made within less than 30 days from diagnosis/Number of people with breast cancer assessed by the specific MDT×100 | 90% |

| 4. People diagnosed with breast cancer who undergo surgical intervention within less than 30 days after decision-making by the specific tumour commission | Surgical delay after MDT | Number of people who undergo surgery in less than 30 days from the decision made by the MDT/Number of people diagnosed with breast cancer subsidiary to surgery×100 | 90% |

| 5. People diagnosed with breast cancer who undergo surgical intervention in less than 30 days after entering the surgical waiting list | Surgical delay after the waiting list | Number of people diagnosed with breast cancer who undergo surgery in less than 30 days after entering the waiting list/Number of people diagnosed with breast cancer subsidiary to surgery×100 | 100% |

| 6. People diagnosed with breast cancer who start adjuvant treatment in less than 6 weeks from the date of the surgical intervention | Delay of adjuvant treatment | Number of people to whom adjuvant treatment is administered in less than 6 weeks from the date of surgery for breast cancer/Number of people diagnosed with breast cancer under adjuvant treatment×100 | 90% |

| 7. People with a diagnosis of breast cancer and surgical interventions undergoing conservative surgery (conservative treatment) | Conservative treatment | Number of people diagnosed with breast cancer who have undergone surgery undergoing conservative surgery/Number of people diagnosed with breast cancer and who have undergone surgery×100 | 50–80% |

| 8. People with diagnosis of breast cancer under immediate reconstructive surgery | Immediate reconstruction | Number of people diagnosed with breast cancer who have undergone immediate reconstructive surgery/Number of people with radical mastectomy for breast cancer×100 | 90% |

| 9. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) | SLNB | Number of people diagnosed with breast cancer who have undergone surgery with selective sentinel node biopsy/Number of people diagnosed with breast cancer and operated on×100 | 50% |

The source of information was the patient medical history. A pseudonymised database was designed to analyse the indicators in a Microsoft Excel Version 16.40 datasheet and continuously updated by two BC specialists, MMC and MMD. The variables collected included demographic information (age and sex), origin, the reason for entering the Integrated Health Care Process and cancer characteristics (clinical examination (palpable nodule in breast or armpit), location (laterality and affected quadrant), type of cancer (in situ or infiltrating and varieties of each), histological grade, tumour stage and existence of recurrence). Besides, a series of variables related to the process were collected: date of diagnosis, the performance of several tests in the same medical consultation, presentation of the case in the multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussion, date of decision-making by the MDT, date of admission to the surgical waiting list, date of intervention, type and date of initiation of adjuvant treatment, type of surgery (tumorectomy or mastectomy), oncoplastic surgery, reconstructive surgery, sentinel lymph node biopsies (SLNB), axillary lymphadenectomy (AL) and its reason. Information was collected from the entire process in most of the cases. Those incomplete cases were not discharged as they were considered useful in analysing part of the indicators.

Data analysisA descriptive analysis was initially performed. We have studied the distribution of frequencies for qualitative variables and central tendency and dispersion measures for quantitative variables. The sociodemographic, clinical and healthcare variables collected were stratified by year of diagnosis and age. The percentage of cases that have reached each of the standard indicators and their 95% confidence interval was estimated, and it was stratified by year of diagnosis, group of age, origin, histological grade and cancer stage. The results were compared by groups using the Chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at a p-value <0.05. All analyses were carried out with the Stata 15.0 statistical package.

ResultsDescriptive analysis of the sampleA total of 487 patients were included, with a mean of 59.6 years old, ranging between 28.8 and 90.1 years. Most patients (99%) were women and referred from primary care (39.5%) or screening (28.6%). Some of the diagnosed cancers (71%) presented a palpable lump in the breast and 9% in the axilla. Appendix 1 presents the main characteristics of the patients studied.

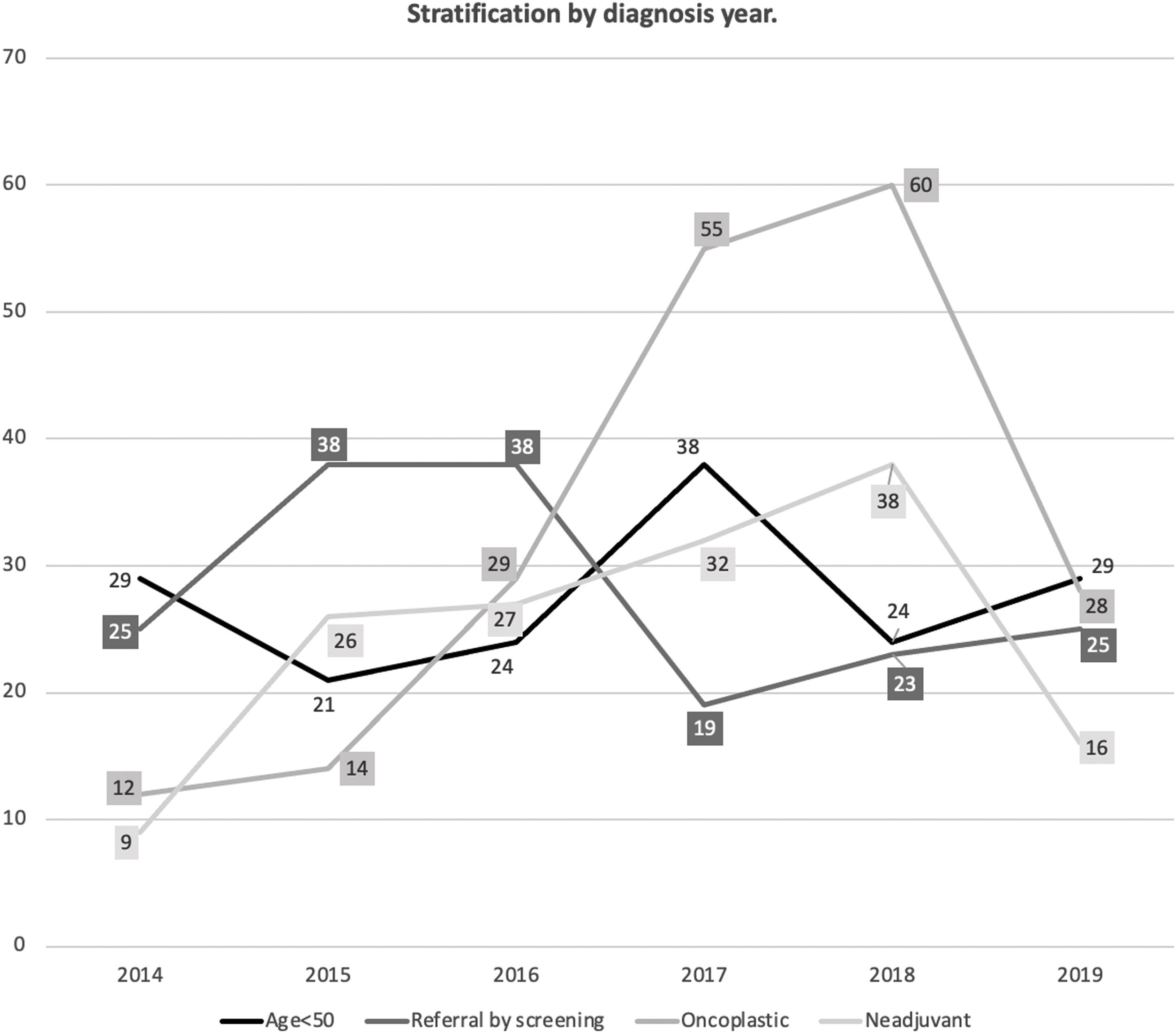

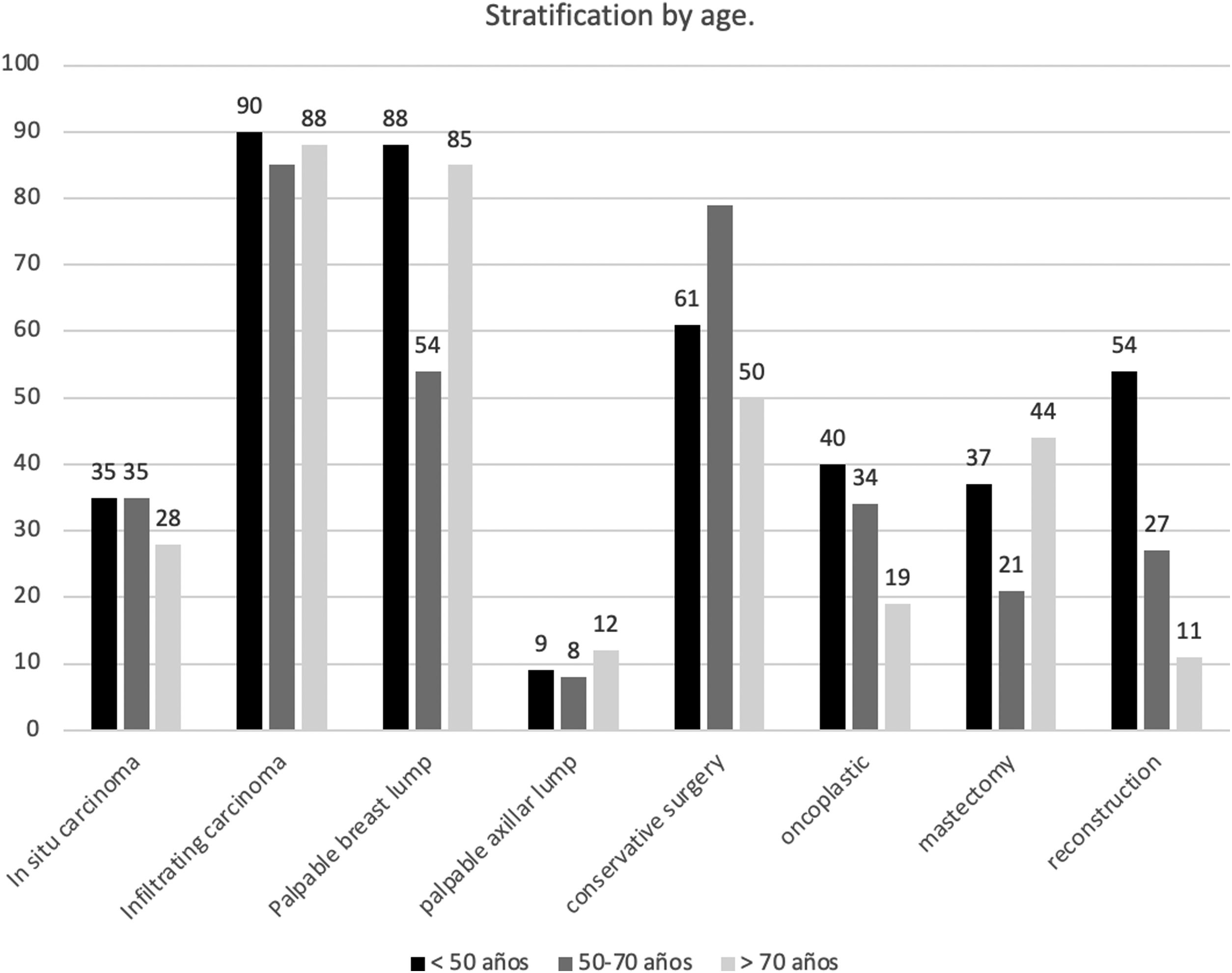

Appendix 2 and Fig. 1 show the stratified analysis according to the year of diagnosis. When stratified by age (Appendix 3 and Fig. 2), the presence of a palpable breast lump at the diagnosis was less usual in those patients of screening age (50–70 years) (62.5% of them came from the screening program (p=0.001)). Conservative surgery (p=0.001) and oncoplastic surgery (p=0.01) were more frequent in young women or those in screening age, while mastectomy was more prevalent in old patients (p=0.001). Reconstructive surgery was performed in 53.62%; 26.58% and 10.04% respectively in each age group (p<0.001). Both chemotherapy (p=0.001) and radiotherapy (p=0.001) were more common in young or middle ages. The SLNB was also more usual in younger women (p=0.001), but there were no significant differences according to age in AL's frequency (p=0.641).

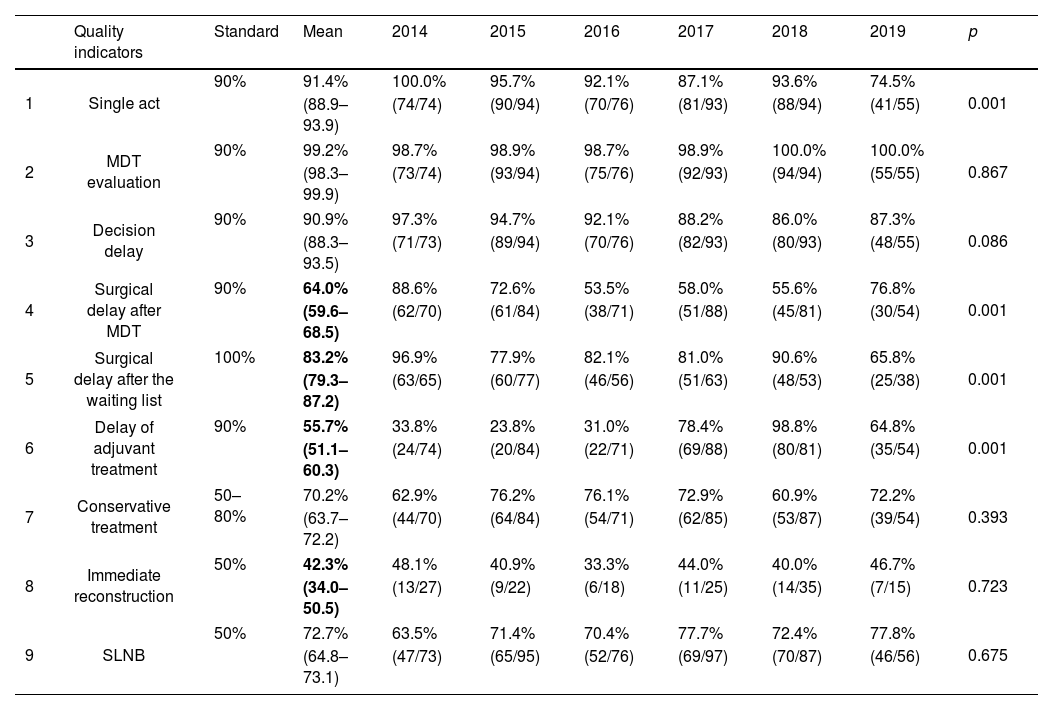

Analysis of quality indicatorsTable 2 shows the estimated values for the QIs stratified by year of study. Globally, all the indicators were above the minimum standard granted in the Integrated Health Care Process from Andalusia,10 except the surgical delay after the decision of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) or after inclusion on the waiting list and the delay in adjuvant treatment. The standard for breast reconstruction was also not reached. When stratifying by diagnosis year, significant differences were observed in all the indicators that did not reach the standard, except in breast reconstruction. All these QIs had a general tendency to decrease their values in recent years except for the delay in adjuvant treatment that improved. There was a decrease in resolution in one only act, below the standard in 2017 and 2019, and in the MDT decision delay, which did not reach the standard after 2017.

The compliance rate of quality indicators according to the year of diagnosis and their deviation from the standard (indicated in grey). In bold, the three indicators whose mean does not meet the standard.

| Quality indicators | Standard | Mean | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Single act | 90% | 91.4% | 100.0% | 95.7% | 92.1% | 87.1% | 93.6% | 74.5% | 0.001 |

| (88.9–93.9) | (74/74) | (90/94) | (70/76) | (81/93) | (88/94) | (41/55) | ||||

| 2 | MDT evaluation | 90% | 99.2% | 98.7% | 98.9% | 98.7% | 98.9% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 0.867 |

| (98.3–99.9) | (73/74) | (93/94) | (75/76) | (92/93) | (94/94) | (55/55) | ||||

| 3 | Decision delay | 90% | 90.9% | 97.3% | 94.7% | 92.1% | 88.2% | 86.0% | 87.3% | 0.086 |

| (88.3–93.5) | (71/73) | (89/94) | (70/76) | (82/93) | (80/93) | (48/55) | ||||

| 4 | Surgical delay after MDT | 90% | 64.0% | 88.6% | 72.6% | 53.5% | 58.0% | 55.6% | 76.8% | 0.001 |

| (59.6–68.5) | (62/70) | (61/84) | (38/71) | (51/88) | (45/81) | (30/54) | ||||

| 5 | Surgical delay after the waiting list | 100% | 83.2% | 96.9% | 77.9% | 82.1% | 81.0% | 90.6% | 65.8% | 0.001 |

| (79.3–87.2) | (63/65) | (60/77) | (46/56) | (51/63) | (48/53) | (25/38) | ||||

| 6 | Delay of adjuvant treatment | 90% | 55.7% | 33.8% | 23.8% | 31.0% | 78.4% | 98.8% | 64.8% | 0.001 |

| (51.1–60.3) | (24/74) | (20/84) | (22/71) | (69/88) | (80/81) | (35/54) | ||||

| 7 | Conservative treatment | 50–80% | 70.2% | 62.9% | 76.2% | 76.1% | 72.9% | 60.9% | 72.2% | 0.393 |

| (63.7–72.2) | (44/70) | (64/84) | (54/71) | (62/85) | (53/87) | (39/54) | ||||

| 8 | Immediate reconstruction | 50% | 42.3% | 48.1% | 40.9% | 33.3% | 44.0% | 40.0% | 46.7% | 0.723 |

| (34.0–50.5) | (13/27) | (9/22) | (6/18) | (11/25) | (14/35) | (7/15) | ||||

| 9 | SLNB | 50% | 72.7% | 63.5% | 71.4% | 70.4% | 77.7% | 72.4% | 77.8% | 0.675 |

| (64.8–73.1) | (47/73) | (65/95) | (52/76) | (69/97) | (70/87) | (46/56) | ||||

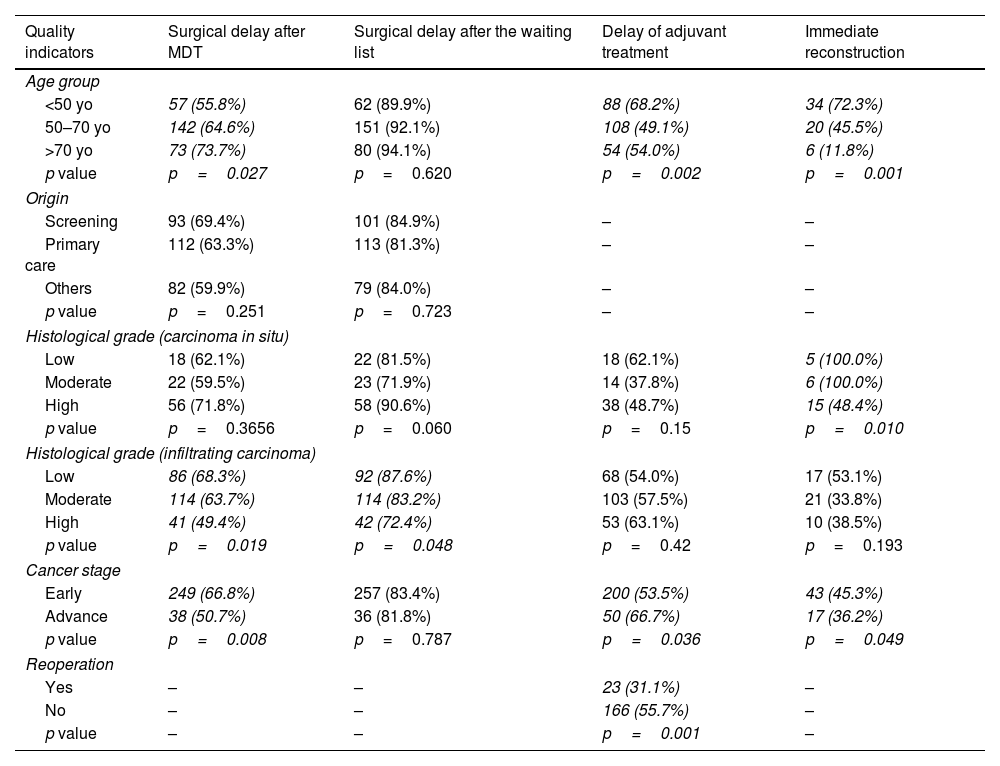

The behaviour of the indicators that did not meet the standards was analysed according to the potentially related sociodemographic and clinical variables (Table 3).

Stratification of the quality indicators by patient characteristics.

| Quality indicators | Surgical delay after MDT | Surgical delay after the waiting list | Delay of adjuvant treatment | Immediate reconstruction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||||

| <50 yo | 57 (55.8%) | 62 (89.9%) | 88 (68.2%) | 34 (72.3%) |

| 50–70 yo | 142 (64.6%) | 151 (92.1%) | 108 (49.1%) | 20 (45.5%) |

| >70 yo | 73 (73.7%) | 80 (94.1%) | 54 (54.0%) | 6 (11.8%) |

| p value | p=0.027 | p=0.620 | p=0.002 | p=0.001 |

| Origin | ||||

| Screening | 93 (69.4%) | 101 (84.9%) | – | – |

| Primary care | 112 (63.3%) | 113 (81.3%) | – | – |

| Others | 82 (59.9%) | 79 (84.0%) | – | – |

| p value | p=0.251 | p=0.723 | – | – |

| Histological grade (carcinoma in situ) | ||||

| Low | 18 (62.1%) | 22 (81.5%) | 18 (62.1%) | 5 (100.0%) |

| Moderate | 22 (59.5%) | 23 (71.9%) | 14 (37.8%) | 6 (100.0%) |

| High | 56 (71.8%) | 58 (90.6%) | 38 (48.7%) | 15 (48.4%) |

| p value | p=0.3656 | p=0.060 | p=0.15 | p=0.010 |

| Histological grade (infiltrating carcinoma) | ||||

| Low | 86 (68.3%) | 92 (87.6%) | 68 (54.0%) | 17 (53.1%) |

| Moderate | 114 (63.7%) | 114 (83.2%) | 103 (57.5%) | 21 (33.8%) |

| High | 41 (49.4%) | 42 (72.4%) | 53 (63.1%) | 10 (38.5%) |

| p value | p=0.019 | p=0.048 | p=0.42 | p=0.193 |

| Cancer stage | ||||

| Early | 249 (66.8%) | 257 (83.4%) | 200 (53.5%) | 43 (45.3%) |

| Advance | 38 (50.7%) | 36 (81.8%) | 50 (66.7%) | 17 (36.2%) |

| p value | p=0.008 | p=0.787 | p=0.036 | p=0.049 |

| Reoperation | ||||

| Yes | – | – | 23 (31.1%) | – |

| No | – | – | 166 (55.7%) | – |

| p value | – | – | p=0.001 | – |

The results that are significant are italicized.

Abbreviation: yo (years old).

After MDT, the delay in surgical treatment (mean 64%, IQR 59.6–68.5) showed an association with age at diagnosis (p=0.027). The indicator value increased and approached the standard as age was raised. The histological grade in IC was also associated with the percentage of compliance: the lower grade BC, the higher compliance (p=0.019) and the cancer stage. This QI compliance was lower in advanced tumours (p=0.008). The percentage of delay compliance in adjuvant treatment (mean 55.7%, IQR 51.1–60.3) was better in women under 50 years old than older (p=0.002), better in advanced stages than in early stages (p=0.489) and better when no reintervention was necessary (p=0.001), but without the standard being met in any case. Regarding the indicator “immediate reconstruction” after mastectomy (mean 42.3%, IQR 34.0–50.5), the standard was widely exceeded in young women, with 72.34%, much higher than that estimated in the remaining age groups (p=0.001) and reached 100% in low histological grades of IC or moderate CIS. It was also significantly higher in the early stages than in advanced stages (45.3% vs 36.2%; p=0.049).

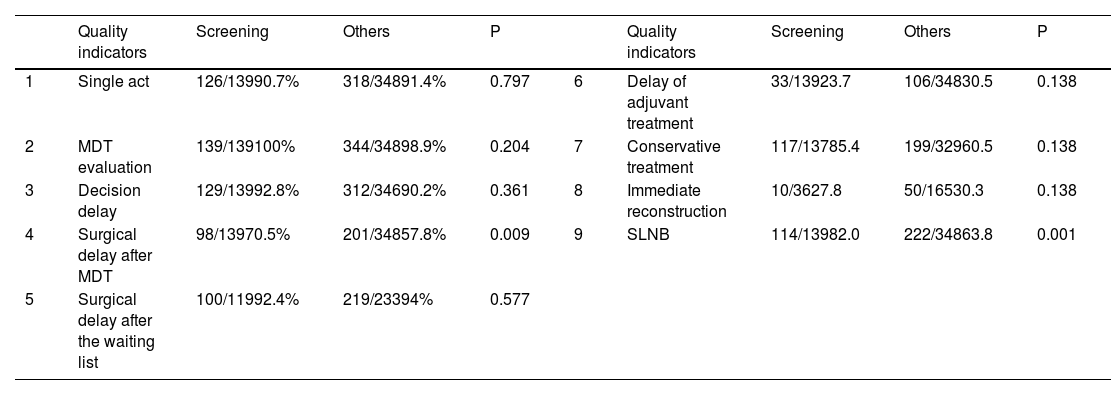

Analysing screening vs non-screening referral (Table 4), patients from the screening had a lower surgical delay after MDT compliance rate than other type of patients (98/139; 70.5% vs 201/348; 57.8%; p=0.009). Screening patients had more SLNB than patients from other referrals patients (114/139; 82.0% vs 238/348; 63.8%; p=0.001). The rest of the QIs had no significant differences between screening and non-screening populations.

Comparison of the QIs compliance rate between screening vs non screening patients.

| Quality indicators | Screening | Others | P | Quality indicators | Screening | Others | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Single act | 126/13990.7% | 318/34891.4% | 0.797 | 6 | Delay of adjuvant treatment | 33/13923.7 | 106/34830.5 | 0.138 |

| 2 | MDT evaluation | 139/139100% | 344/34898.9% | 0.204 | 7 | Conservative treatment | 117/13785.4 | 199/32960.5 | 0.138 |

| 3 | Decision delay | 129/13992.8% | 312/34690.2% | 0.361 | 8 | Immediate reconstruction | 10/3627.8 | 50/16530.3 | 0.138 |

| 4 | Surgical delay after MDT | 98/13970.5% | 201/34857.8% | 0.009 | 9 | SLNB | 114/13982.0 | 222/34863.8 | 0.001 |

| 5 | Surgical delay after the waiting list | 100/11992.4% | 219/23394% | 0.577 |

To our knowledge, there were not found similar studies about BC QIs in Spain. However, their evaluation is considered essential for adequate control of the process, identifying areas for improvement and providing possible solutions and improvement plans based on objective data.10

Although we have summarised our specific population characteristics, our study's global purpose was not to focus on the distinctive aspects of our population, which would only provide relevant information for our Health Area. Instead, we wanted to study the QIs degree of compliance rate to subsequently analyse the variables that possibly modify them and later propose improvement measures. All the data collected could allow comparing diverse populations, and more complex studies and patients with different characteristics could be studied.

The distribution by age and origin of our series, similar to what was described by other authors,15,16 revealed that most of these were diagnosed early (by screening or by opportunistic screening) of the General Practitioners. There was no doubt that the shorter time spent in the diagnosis, waiting time for surgery and adjuvant treatment affected patients’ well-being and survival and increased care quality.17,18 BC was more frequently located in external quadrants in our study. This was supported by other studies since there would be more glandular tissue in this area.19 Moreover, our study observed that the number of patients diagnosed with the screening has increased in recent years, suggesting that it has improved its effectiveness and coverage. Although primary care was the most frequent origin, more than half of the patients in the age of screening tests came from the screening.

The indication of neoadjuvant treatment has slightly increased over the years, probably due to the appearance of new advances in management and the approval of new protocols. Likewise, there was an increase in oncoplastic surgery over time, possibly due to increasing training and qualification of the surgical team, which would allow the performance of more complex surgeries.

Some of these indicators, such as “MDT assessment” of each case, “performance of conservative surgery” and “SLNB”, showed an excellent rate of adherence to the recommendations. Others, such as “delay in surgical treatment after MDT” and “delay in surgical treatment after inclusion in the waiting list”, which in both cases might be less than 30 days, “delay in adjuvant treatment less than 6 weeks” and “immediately reconstruction post-mastectomy” obtained an average compliance rate that did not reach the required quality standards. In the first case, it was necessary to highlight a contrary effect to what is expected when stratifying by age, stage or histological grade in IC, which could probably be due to the antecedent or not of neoadjuvant treatment. The frequency of neoadjuvant treatment has increased, particularly in younger women. The mean delay in surgical treatment was longer in women treated with neoadjuvant therapy (150.1 vs 26.9 days; p<0.001; results not shown). This would mean that either the standards were corrected, or the delay indicator was restricted exclusively to women treated without neoadjuvant therapy.

Concerning immediate reconstruction after mastectomy, the compliance rate was always below standard. This technique, widely recommended nowadays,20 could be performed using an immediate or delayed prosthesis (by placing a breast expander). There was no current consensus on which would be the best option.21–23 In our study, reconstruction was performed by placing an expander and delayed prosthesis. Nowadays, there is a growing tendency to perform conservative surgery.6,22,24,25 Furthermore, women who have chosen mastectomy would generally have a more advanced stage, with an invasion of adjacent tissues, so the placement of an expander or prosthesis would not always be feasible. Age is also a relative contraindication to reconstruction.26 The stratification by age showed an excellent result regarding the standard for younger women. However, the Integrated Health Care Process did not contemplate the data stratification to assess the process's quality. The behaviour of these QIs regarding the preoperative stage has confirmed those mentioned above. The earliest stages were the subsidiary stages of expander or prosthesis placement, and in them, a significantly higher percentage was obtained. After reviewing all the patients who had not been reconstructed, there was at least one relative contraindication criterion for immediate reconstruction in the majority of cases.

Therefore, 50% of cases with immediate reconstruction after mastectomy could be an excessively high percentage; especially since more and more conservative surgery has been indicated with or without oncoplastic surgery, and those in which a mastectomy was frequently performed would present relative or absolute contraindications (such as advanced age, invasion of adjacent tissues, or others). Besides, this breast reconstruction QI penalised health areas that would treat older patients and with worse access to screening programs in contrast to other indicators such as surgical delay and single-act diagnosis, which were more independent of the mix of cases and, therefore, more valuable to identify deficiencies that could be improved. So, we could consider that this standard was not well defined and that its modification to a lower percentage of compliance should be considered, or its wording should be modified. This quality indicator should refer exclusively to young women in whom radical mastectomy would be performed, and there would not be other contraindication for reconstructive surgery.

For other indicators, the result was dependent on the available resources, thus, for example, the “adjuvant treatment delay” indicator had improved in 2017 and after, when the availability of oncologists in the hospital has stabilised. The differences observed by age for this indicator suggested that preference was given to younger women in any case. Although the process indicators should not depend on the available resources, and the non-compliance with these indicators should signal to governments and managers the need to provide the available resources to ensure the best processes available to patients, the reality is that resources are not equal for all the areas in the worldwide. So, this study wants to highlight which resources should be improved to ameliorate each QIs compliance rate. This would make it possible to follow up on a population during the years and analyse whether the proposed changes improved.

ConclusionsThis is the first study developed in our country that analyses the Qis’ fulfilment in a Breast Unit. To estimate these indicators, it was required to keep a record of the cancer cases treated, which is essential for evaluating the entire process. Although the QIs of the process should not depend on the available resources, and the non-compliance should indicate the need to produce available governmental resources and policies to guarantee the best procedures convenient to patients, the fact is that resources are not the same for all the worldwide locations. So, not all indicators would be equally helpful in improving the Integrated Health Care Process. While some might depend on the available resources and be valued according to them, others would depend on the mix of patients or complementary treatments. In these cases, it would be essential to identify the specific target populations for estimating the indicator or provide standards stratified by the variables that have influenced them, such as age, the use of adjuvant treatment, or the type of surgery. The availability of data from other hospitals, regions and countries will allow us to compare our results and show improvement strategies.

Ethical approval and consent to participateThe study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Bioethics Committee from the University of Granada (Ref n. 0922-N-17). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

FundingNo financial support or sponsorship.

Authors’ contributionsEach author certifies that he/she has made a direct and substantial contribution to the conception and design of the study, development of the search strategy, the establishment of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, data extraction, analysis and interpretation. MMC was involved in the design of the study, literature search, data collection and analysis, quality appraisal and writing. MMD was involved in the design of this study, analysis of data and writing. LM was involved in writing. ABC was involved in the design of this study, data collection and analysis, writing and provided critical revision of the paper. KSK was involved in writing and provided critical revision of the paper. All authors read and provided the final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study.