Evidence supports that admitting patients with stroke during different hospital work periods is related to distinct outcomes. We aimed to analyse outcomes in patients according to the period and time of admission to the stroke unit.

MethodsRetrospective study. For purposes of data analysis, patients were grouped according to the following time periods: (a) day of the week, (b) period of the year, (c) shift. We analysed demographic characteristics, stroke type and severity, and the percentage undergoing thrombolysis in each group. The measures used to evaluate early outcomes were the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), neurological complications (NC), and in-hospital mortality. Functional outcome at 3 months was determined using the modified Rankin scale.

ResultsThe stroke unit admitted 1250 patients. We found NC to be slightly more frequent for weekend admissions than for weekday admissions, but this trend does not seem to have influenced in-hospital mortality. Regarding functional outcome at 3 months, 67.0% of weekday vs 60.7% of weekend admissions were independent (P=.096), as were 65.5% of patients admitted during the academic months vs 63.5% of those admitted during summer holidays (P=.803). We identified no significant differences in 3-month mortality linked to the day or period of admission; however, for the variable ‘shift’, 13.2% of the patients died during the morning shift, 11.5% during the afternoon shift, and 6.0% during the night shift (P=.017). We identified a trend towards higher rates of thrombolysis administration on weekdays, during the morning shift, and during the academic months.

ConclusionsTime of admission to the stroke unit did not affect early outcomes or functional independence at 3 months.

Existe evidencia de que el ingreso de pacientes con ictus en diferentes periodos laborales influye en su evolución. Analizamos la evolución de los pacientes con relación al momento del ingreso en una unidad de ictus.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo. Se agrupó a los pacientes considerando los siguientes periodos: a) día de la semana, b) periodo del año y c) turno de trabajo. Analizamos características demográficas, tipo y gravedad del ictus y porcentaje de trombólisis. Determinamos la evolución precoz considerando: la National Institute of Heath Stroke Scale (NIHSS), complicaciones neurológicas (CN) y mortalidad hospitalaria, y situación funcional (SF) a 3 meses mediante la escala modificada de Rankin.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 1.250 pacientes. Las CN fueron más frecuentes durante el fin de semana que en los días laborales, sin influir en la mortalidad hospitalaria. Respecto a la SF a 3 meses, el 67,0% de pacientes ingresados en días laborales vs. 60,7% durante el fin de semana (p=0,096), el 65,5% de los pacientes ingresados durante los meses académicos vs. 63,5% durante las vacaciones de verano (p=0,803) eran independientes. No identificamos diferencias significativas en la mortalidad a 3 meses según el día o periodo del año; sin embargo, para la variable turno de trabajo, el 13,2% de los pacientes ingresados durante la mañana, el 11,5% por la tarde y el 6,0% durante el turno de noche fallecieron (p=0,017). Observamos una tendencia a realizar más fibrinólisis en días laborables, turno de la mañana y meses académicos.

ConclusionesEl momento del ingreso en la unidad de ictus no influyó en la evolución precoz ni en la situación de independencia a 3 meses.

The development of multidisciplinary teams and structures specifically focused on the care of acute stroke patients has meant a substantial change in the prognosis of these patients.1 Several studies have shown that implementing organised systems for stroke care and specific treatment protocols is associated with lower mortality and dependence rates and significantly reduces the need for institutionalisation.2–4 However, hospital schedules may have an impact on patient prognosis: evidence shows that patients admitted during the weekend undergo fewer diagnostic tests and are less likely to receive reperfusion therapy (ischaemic stroke) or surgery (haemorrhagic stroke).5–8 According to the Canadian Stroke Network, stroke patients admitted during the weekend present higher mortality rates than those admitted during weekdays regardless of stroke severity.9 Other studies report that being admitted during the weekend increases the probability of death by 17%.10 There is controversy regarding whether implementing treatment protocols that standardise care to stroke patients in stroke units (SU) could prevent differences in quality regardless of time of admission, thereby minimising differences in mortality and functional outcomes.11,12 Some authors point out that fewer human and diagnostic resources are available during the weekend. In the context of the Spanish healthcare system, this situation may also take place at other moments of the day (work shifts) and the year. In fact, some studies have shown that resources are limited during the night shift, which is associated with higher mortality rates.13,14 In light of this situation, we analysed whether progression and functional outcomes of patients vary depending on the work shift or period of the year. To our knowledge, no studies have addressed the differences between admitting stroke patients during the summer holidays and the rest of the year.

We aimed to evaluate whether early outcomes and functional independence at 3 months varied depending on the time of admission to the SU.

Subjects and methodsThis retrospective study included all consecutive patients admitted to an SU between June 2007 and December 2009. Our SU provides care to a community of 411633 residents and is the reference centre for a population of 1100000 inhabitants. The structure, characteristics, and action protocols of our SU were described in a previous study.1

All admitted patients were prospectively entered in a database. Patients were classified into 3 groups by stroke type: transient ischaemic attack, ischaemic stroke, and haemorrhagic stroke.15 For the purposes of data analysis, we identified the time periods that may result in different outcomes according to the work schedule at our SU. We grouped patients according to time of admission to the SU (taSU): (a) day of the week (weekdays [Monday 08:00 to Friday 14:59] or weekend [Friday 15:00 to 7:59 Monday]), (b) period of the year (summer holidays [1 July to 31 August] or academic year [1 September to 30 June]), and (c) work shift (morning [08:00-14:59], afternoon [15:00-21:59], and night [22:00-07:59]). We also analysed the following variables: age; sex; premorbid scores ≤2 points on the modified Rankin Scale (mRS)16 (based on the patient's functional situation before stroke as a result of comorbidities); history of arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, or stroke; stroke severity at admission (NIH Stroke Scale, NIHSS)17; time elapsed between symptom onset and assessment by a neurologist, and duration of stay at the SU. Early outcomes were analysed based on the following variables: differences between NIHSS scores at admission and at discharge (differential NIHSS), neurological complications (symptomatic or asymptomatic haemorrhagic transformation, recurrent strokes, hydrocephalus, cerebral oedema, haematoma expansion, delirium, epileptic seizures), and in-hospital mortality.

Each patient's functional situation at 3 months was assessed using the mRS at the outpatient follow-up consultation or via a telephone interview by a trained nurse.

We also determined the percentage of patients receiving intravenous reperfusion treatments in each group.

Statistical analysisIn the descriptive analysis, categorical variables were expressed as absolute frequencies (percentages) whereas quantitative variables were presented as mean±standard deviation (SD).

The statistical association was determined using the Pearson chi-square test for qualitative variables, and either the t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative variables depending on the sample distribution. The sample distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. We performed a logistic regression analysis to determine the factors associated with in-hospital mortality, mortality at 90 days, and functional outcome at 3 months. The multivariate analysis included the factors that were shown to be significantly associated with the dependent variable in the univariate analysis (P<.20). The variables that remained in the model were those that maintained the association with the same significance level (P<.20).

P-values <.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analysed using SPSS statistical software version 17.

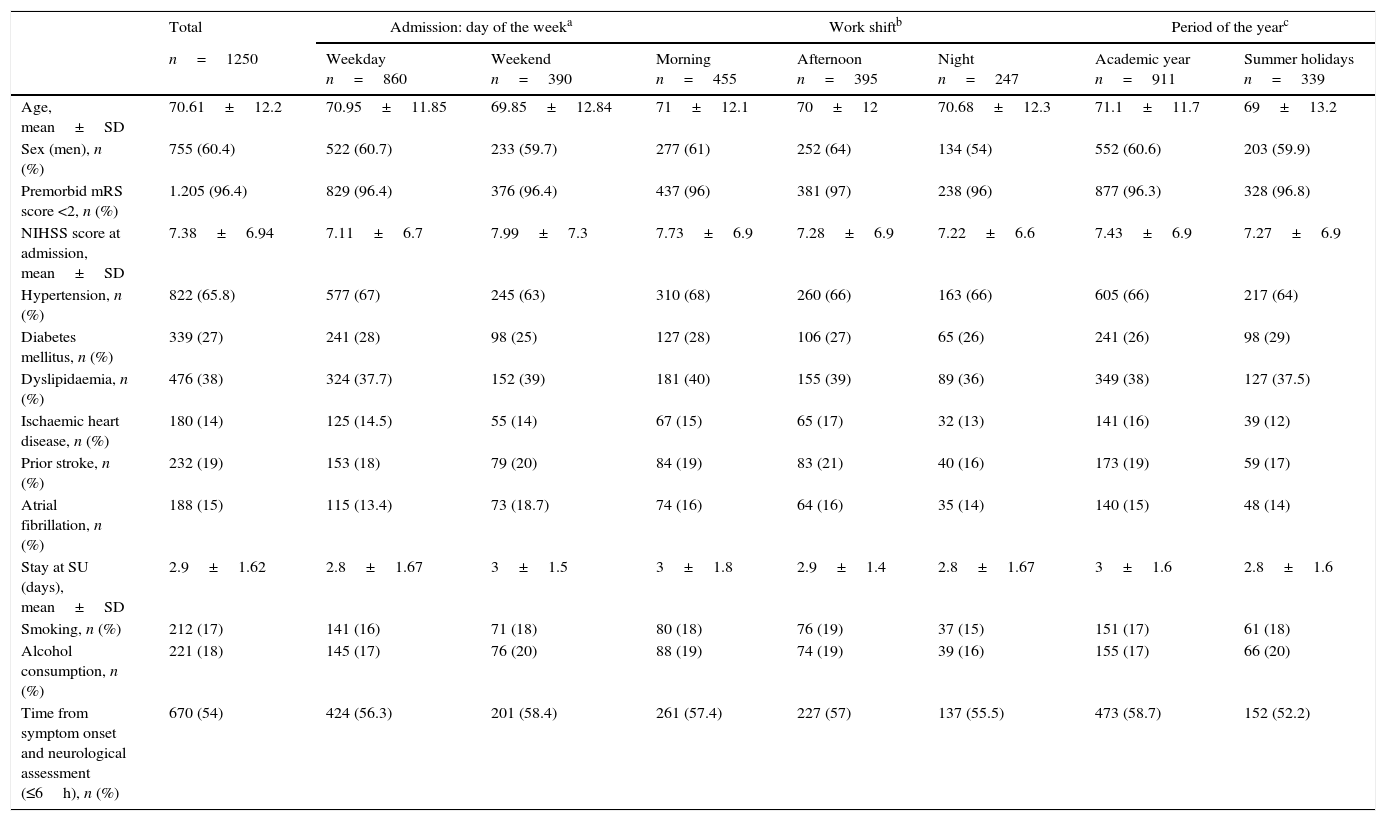

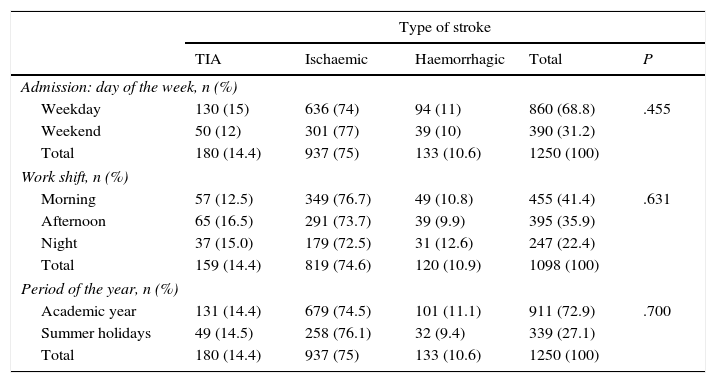

ResultsA total of 1250 patients were admitted to the SU during the study period, all of whom were used to analyse the ‘day of the week’ and ‘period of the year’ variables. The data required for the ‘work shift’ variable were only available in 1098 patients. Table 1 shows baseline patient characteristics by taSU group. Mean age was 70.6±12.2 years. Men accounted for 60.4% of the total. Regarding stroke type, 75% of the patients had an ischaemic stroke, 10.6% haemorrhagic stroke, and 14.4% transient ischaemic attack. Broken down by subtype, 36.1% of strokes were atherothrombotic, 26.7% cardioembolic, 25.9% of undetermined aetiology, 8.7% lacunar, and 2.6% infrequent. No significant differences were found between stroke subtypes regarding the 3 scheduling variables except for ‘day of the week’, where the percentage of patients admitted with lacunar stroke was higher on weekdays than that of patients admitted during the weekend (10.3% vs 5.3%; P=.025). Regarding the day of the week, 68.8% of patients were admitted on weekdays, whereas 31.2% were admitted during the weekend (Table 2). In addition, 41.1% were admitted during the morning shift, 35.9% during the afternoon shift, and 22.4% during the night shift; 27.1% were admitted during the summer holidays, and 72.9% during the academic year.

Characteristics of all stroke patients at time of admission to the SU.

| Total | Admission: day of the weeka | Work shiftb | Period of the yearc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=1250 | Weekday n=860 | Weekend n=390 | Morning n=455 | Afternoon n=395 | Night n=247 | Academic year n=911 | Summer holidays n=339 | |

| Age, mean±SD | 70.61±12.2 | 70.95±11.85 | 69.85±12.84 | 71±12.1 | 70±12 | 70.68±12.3 | 71.1±11.7 | 69±13.2 |

| Sex (men), n (%) | 755 (60.4) | 522 (60.7) | 233 (59.7) | 277 (61) | 252 (64) | 134 (54) | 552 (60.6) | 203 (59.9) |

| Premorbid mRS score <2, n (%) | 1.205 (96.4) | 829 (96.4) | 376 (96.4) | 437 (96) | 381 (97) | 238 (96) | 877 (96.3) | 328 (96.8) |

| NIHSS score at admission, mean±SD | 7.38±6.94 | 7.11±6.7 | 7.99±7.3 | 7.73±6.9 | 7.28±6.9 | 7.22±6.6 | 7.43±6.9 | 7.27±6.9 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 822 (65.8) | 577 (67) | 245 (63) | 310 (68) | 260 (66) | 163 (66) | 605 (66) | 217 (64) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 339 (27) | 241 (28) | 98 (25) | 127 (28) | 106 (27) | 65 (26) | 241 (26) | 98 (29) |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 476 (38) | 324 (37.7) | 152 (39) | 181 (40) | 155 (39) | 89 (36) | 349 (38) | 127 (37.5) |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 180 (14) | 125 (14.5) | 55 (14) | 67 (15) | 65 (17) | 32 (13) | 141 (16) | 39 (12) |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 232 (19) | 153 (18) | 79 (20) | 84 (19) | 83 (21) | 40 (16) | 173 (19) | 59 (17) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 188 (15) | 115 (13.4) | 73 (18.7) | 74 (16) | 64 (16) | 35 (14) | 140 (15) | 48 (14) |

| Stay at SU (days), mean±SD | 2.9±1.62 | 2.8±1.67 | 3±1.5 | 3±1.8 | 2.9±1.4 | 2.8±1.67 | 3±1.6 | 2.8±1.6 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 212 (17) | 141 (16) | 71 (18) | 80 (18) | 76 (19) | 37 (15) | 151 (17) | 61 (18) |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 221 (18) | 145 (17) | 76 (20) | 88 (19) | 74 (19) | 39 (16) | 155 (17) | 66 (20) |

| Time from symptom onset and neurological assessment (≤6h), n (%) | 670 (54) | 424 (56.3) | 201 (58.4) | 261 (57.4) | 227 (57) | 137 (55.5) | 473 (58.7) | 152 (52.2) |

SD, standard deviation; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

P>.05.

Stroke types by time of admission in our sample.

| Type of stroke | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIA | Ischaemic | Haemorrhagic | Total | P | |

| Admission: day of the week, n (%) | |||||

| Weekday | 130 (15) | 636 (74) | 94 (11) | 860 (68.8) | .455 |

| Weekend | 50 (12) | 301 (77) | 39 (10) | 390 (31.2) | |

| Total | 180 (14.4) | 937 (75) | 133 (10.6) | 1250 (100) | |

| Work shift, n (%) | |||||

| Morning | 57 (12.5) | 349 (76.7) | 49 (10.8) | 455 (41.4) | .631 |

| Afternoon | 65 (16.5) | 291 (73.7) | 39 (9.9) | 395 (35.9) | |

| Night | 37 (15.0) | 179 (72.5) | 31 (12.6) | 247 (22.4) | |

| Total | 159 (14.4) | 819 (74.6) | 120 (10.9) | 1098 (100) | |

| Period of the year, n (%) | |||||

| Academic year | 131 (14.4) | 679 (74.5) | 101 (11.1) | 911 (72.9) | .700 |

| Summer holidays | 49 (14.5) | 258 (76.1) | 32 (9.4) | 339 (27.1) | |

| Total | 180 (14.4) | 937 (75) | 133 (10.6) | 1250 (100) | |

TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

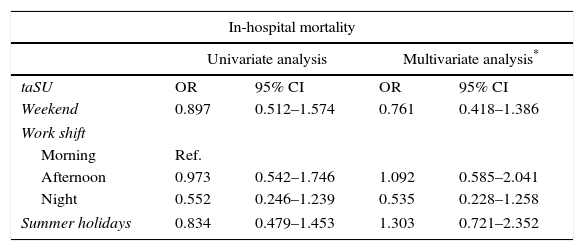

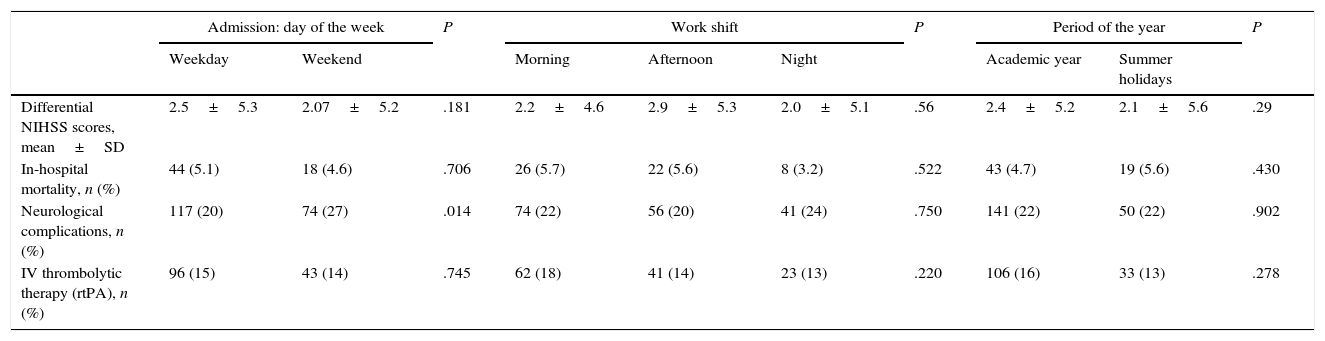

We found no significant differences in terms of age; sex; premorbid mRS scores (mRS≤2); history of arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, stroke, or atrial fibrillation; time elapsed from symptom onset to neurological assessment; and duration of stay at the SU (Tables 1 and 2). Table 3 summarises in-hospital mortality data by taSU group. Mean baseline NIHSS score was 7.38±6.94 for the entire sample. We found no significant differences in NIHSS scores between patients admitted during weekdays (7.11±6.7) and those admitted during the weekend (7.99±7.3); between patients admitted during the summer holidays (7.43±6.9) and those admitted during the academic year (7.27±6.9); or between patients admitted during the morning (7.73±6.9), afternoon (7.28±6.9), and night shifts (7.22±6.6) (Table 1). Regarding early outcomes, the mean differential NIHSS score was 2.37±5.3; no statistical differences were found between taSU groups. Likewise, we found no significant differences in in-hospital mortality rates between patients admitted during weekdays and those admitted during the weekend, between patients admitted during the summer holidays and those admitted during the academic year, or between patients admitted during the morning, afternoon, and night shifts. The univariate and multivariate regression models were adjusted for age, sex, stroke type, premorbid mRS scores <2, and NIHSS scores, and found no significant differences between groups in terms of in-hospital mortality (Table 3). In-hospital mortality was associated with stroke progression (haemorrhagic transformation, cerebral oedema, recurrence) in 71% of the cases, heart complications in 16.2%, respiratory complications in 6.4%, and infections in 6.4%.

Logistic regression model for in-hospital mortality by time of admission to the SU.

| In-hospital mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis* | |||

| taSU | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Weekend | 0.897 | 0.512–1.574 | 0.761 | 0.418–1.386 |

| Work shift | ||||

| Morning | Ref. | |||

| Afternoon | 0.973 | 0.542–1.746 | 1.092 | 0.585–2.041 |

| Night | 0.552 | 0.246–1.239 | 0.535 | 0.228–1.258 |

| Summer holidays | 0.834 | 0.479–1.453 | 1.303 | 0.721–2.352 |

taSU, time of admission to stroke unit.

Intravenous reperfusion therapy was slightly more frequently administered to patients admitted during weekdays (11.2%), the morning shift (13.6%), and the academic year (11.6%); these differences, however, did not reach statistical significance. Twenty-seven percent of the patients admitted during the weekend presented NC vs 20% of patients admitted during weekdays (P=.014). We found no significant differences between the remaining groups (Table 4).

Early outcomes by time of admission to the SU.

| Admission: day of the week | P | Work shift | P | Period of the year | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekday | Weekend | Morning | Afternoon | Night | Academic year | Summer holidays | ||||

| Differential NIHSS scores, mean±SD | 2.5±5.3 | 2.07±5.2 | .181 | 2.2±4.6 | 2.9±5.3 | 2.0±5.1 | .56 | 2.4±5.2 | 2.1±5.6 | .29 |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 44 (5.1) | 18 (4.6) | .706 | 26 (5.7) | 22 (5.6) | 8 (3.2) | .522 | 43 (4.7) | 19 (5.6) | .430 |

| Neurological complications, n (%) | 117 (20) | 74 (27) | .014 | 74 (22) | 56 (20) | 41 (24) | .750 | 141 (22) | 50 (22) | .902 |

| IV thrombolytic therapy (rtPA), n (%) | 96 (15) | 43 (14) | .745 | 62 (18) | 41 (14) | 23 (13) | .220 | 106 (16) | 33 (13) | .278 |

SD, standard deviation; IV, intravenous; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

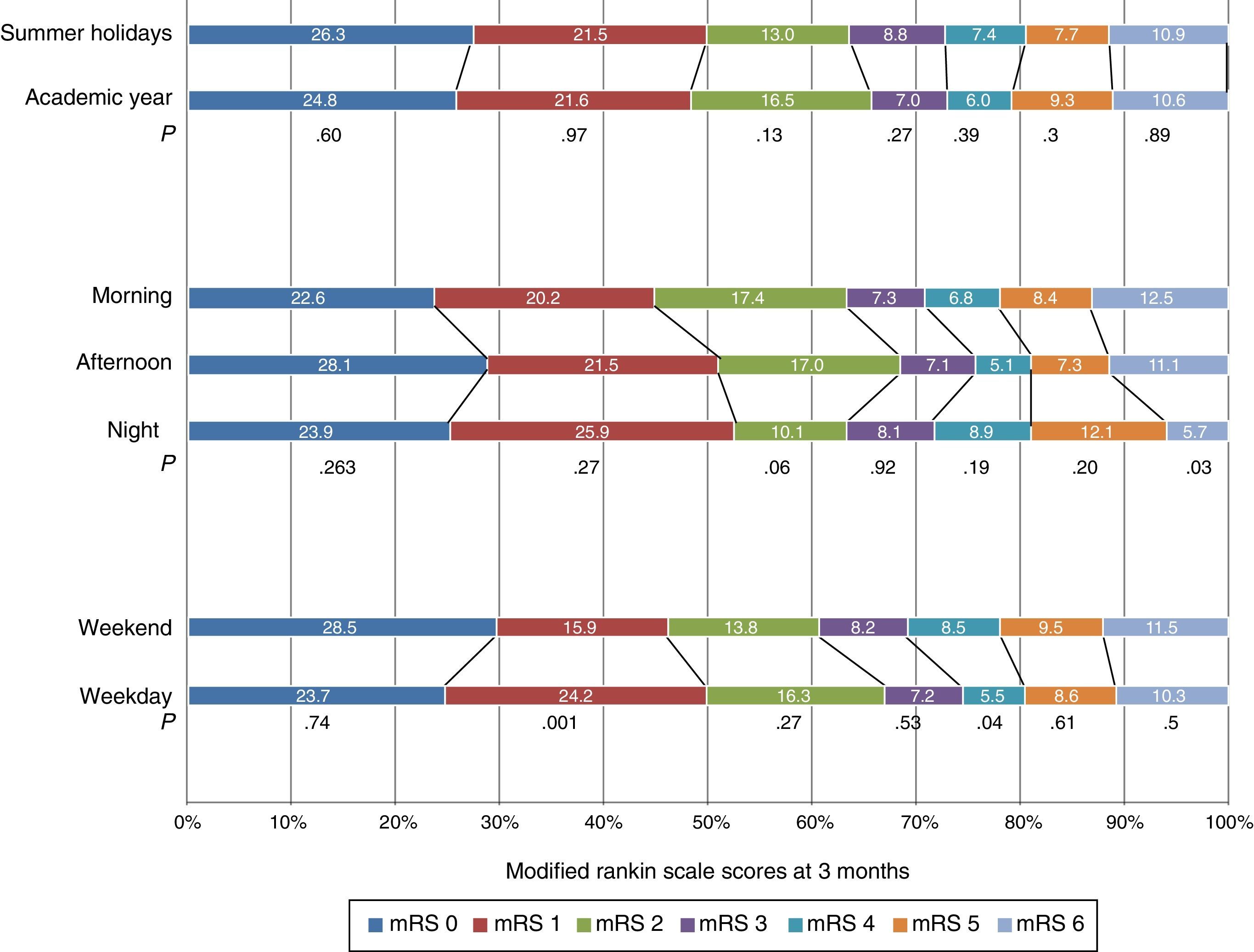

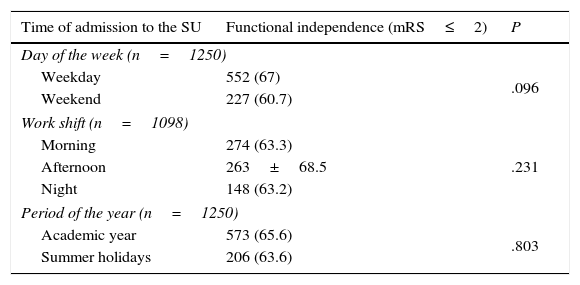

Regarding patient functionality at 3 months, 67% of patients admitted on weekdays and 60.7% of patients admitted during the weekend were independent (P=.096). Likewise, 65.5% of patients admitted during the academic year vs 63.5% of patients admitted during the summer holidays (P=.803) were independent at 3 months. Regarding differences between patients admitted during different work shifts, no significant differences were seen in the percentage of patients who were functionally independent at 3 months (Table 5).

Patients with favourable outcomes at 3 months sorted by time of admission to the SU.

| Time of admission to the SU | Functional independence (mRS≤2) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Day of the week (n=1250) | ||

| Weekday | 552 (67) | .096 |

| Weekend | 227 (60.7) | |

| Work shift (n=1098) | ||

| Morning | 274 (63.3) | .231 |

| Afternoon | 263±68.5 | |

| Night | 148 (63.2) | |

| Period of the year (n=1250) | ||

| Academic year | 573 (65.6) | .803 |

| Summer holidays | 206 (63.6) | |

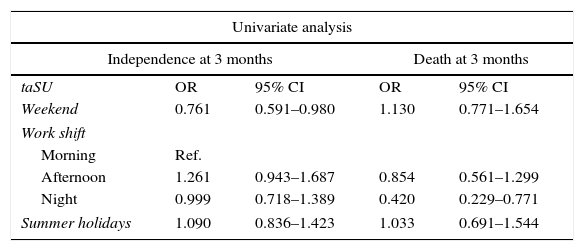

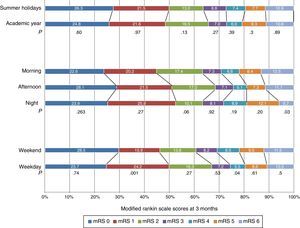

Similarly, the logistic regression analyses demonstrated no significant differences in functional independence between the different study groups, or in mortality rates at 3 months between patients admitted at different days of the week or periods of the year. However, we did find significant differences for the ‘work shift’ variable: the mortality rate at 3 months was 12.5% for patients admitted during the morning shift, 11.1% for the afternoon shift, and 5.7% for the night shift (P=.03). Statistical significance remained the same after performing the adjusted logistic regression analysis (Fig. 1, Table 6).

Logistic regression models for functional outcomes at 3 months.

| Univariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independence at 3 months | Death at 3 months | |||

| taSU | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Weekend | 0.761 | 0.591–0.980 | 1.130 | 0.771–1.654 |

| Work shift | ||||

| Morning | Ref. | |||

| Afternoon | 1.261 | 0.943–1.687 | 0.854 | 0.561–1.299 |

| Night | 0.999 | 0.718–1.389 | 0.420 | 0.229–0.771 |

| Summer holidays | 1.090 | 0.836–1.423 | 1.033 | 0.691–1.544 |

| Multivariate analysis* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independence at 3 months | Death at 3 months | |||

| taSU | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Weekend | 0.786 | 0.571–1.084 | 1.007 | 0.657–1.545 |

| Work shift | ||||

| Morning | Ref. | |||

| Afternoon | 1.219 | 0.839–1.772 | 0.861 | 0.536–1.383 |

| Night | 0.896 | 0.590–1.360 | 0.340 | 0.173–0.668 |

| Summer holidays | 1.340 | 0.957–1.876 | 1.103 | 0.700–1.738 |

taSU, time of admission to the stroke unit.

Our results indicate that admitting patients to an SU at different work periods (holidays vs academic year, weekdays vs weekends, work shifts) has no impact on early outcomes or functional situations at 3 months. In addition, the different work periods had no effect on either the percentage of patients receiving thrombolysis or in-hospital mortality rates between groups. Although the percentage of patients experiencing mild to severe NC was slightly higher among patients admitted during the weekend than in those admitted on weekdays, NC seem to have no significant impact on early mortality rates among the different groups. Our results cannot be attributed to discrepancies in baseline characteristics of the study population since all demographic variables and stroke characteristics were homogeneously distributed.

Other studies conducted in SUs have suggested that stroke care management systems may minimise difficulties caused by admission during different work periods, which in turn prevents poor outcomes.11,12,18–20

We found no significant differences in in-hospital mortality rates between the different taSU groups. Our results agree with those reported by Albright et al.11 and Martinez et al.12 Likewise, in line with other studies conducted in SUs which addressed mortality and functional situation at 3 months, our results demonstrate that these prognostic variables are not affected by the day of the week the patient was admitted. McKinney et al.21 found that mortality rates of patients admitted during the weekend increased by 5% in centres lacking specialised stroke care. We should point out that we found no differences in mortality rates at 3 months between groups admitted at different periods of the year. However, the group of patients admitted during the night shift displayed lower mortality rates than the group admitted during other shifts. A number of other factors, including chance, may have contributed to these results.

Although some studies suggest that reduced availability of hospital staff and resources during the weekends may lead to lower numbers of diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, other studies analysing the ‘weekend effect’ have reported higher rates of thrombolytic therapy during the night shift or at the weekend.22 According to the study by Hoh et al.,23 patients admitted during the weekend are 11% more likely to receive thrombolytic therapy. In our study, we observed a non-significant tendency to perform this procedure more frequently during the morning shift, weekdays, and academic year.

It is difficult to compare results and draw conclusions due to the methodological differences of the studies analysing the ‘weekend effect’. These studies have several limitations, including the small sample size in the studies conducted in SUs,12 differences in resource availability and neurological staffing ratios by hospital, and the retrospective design of studies with larger sample sizes.24 Our study has its own limitations, especially the retrospective analysis of data obtained prospectively and the fact that it was conducted in only one hospital. In addition, some factors that were not controlled after hospital discharge may have influenced mortality rates at 3 months.

ConclusionsOur results show that the time of admission to our SU does not affect early outcomes or functional independence at 3 months. This may be due to doctors and nursing staff adhering strictly to action protocols, which guarantees systematisation of patient care regardless of the time of admission.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank the doctors from the neurology department (Mar Caballero Muñoz, Alfonso Falcón García, Gonzalo Gámez-Leyva, Pedro Enrique Jiménez Caballero, and Ana Serrano Cabrera) for their help in integrating all the study patients from the SU in the database.

Please cite this article as: Romero Sevilla R, Portilla Cuenca JC, López Espuela F, Redondo Peñas I, Bragado Trigo I, Yerga Lorenzana B, et al. Un sistema organizado de atención al ictus evita diferencias en la evolución de los pacientes en relación con el momento de su ingreso en una unidad de ictus. Neurología. 2016;31:149–156.

Partially presented as an oral communication at the 65th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology, Barcelona, November 2013.