Herpes simplex encephalitis is the most frequent type of sporadic viral encephalitis in immunocompetent adults, with herpes simplex virus 1 accounting for over 90% of cases. Symptoms include focal encephalopathy with headache, fever, impaired consciousness, and psychiatric symptoms due to the involvement of limbic structures. The diagnostic technique of choice is a polymerase chain reaction assay of a CSF sample.1 As false negatives or late diagnosis may delay treatment onset, imaging studies play a fundamental role both in early diagnosis and in analysing the absence of symptom improvement in the weeks following treatment onset.

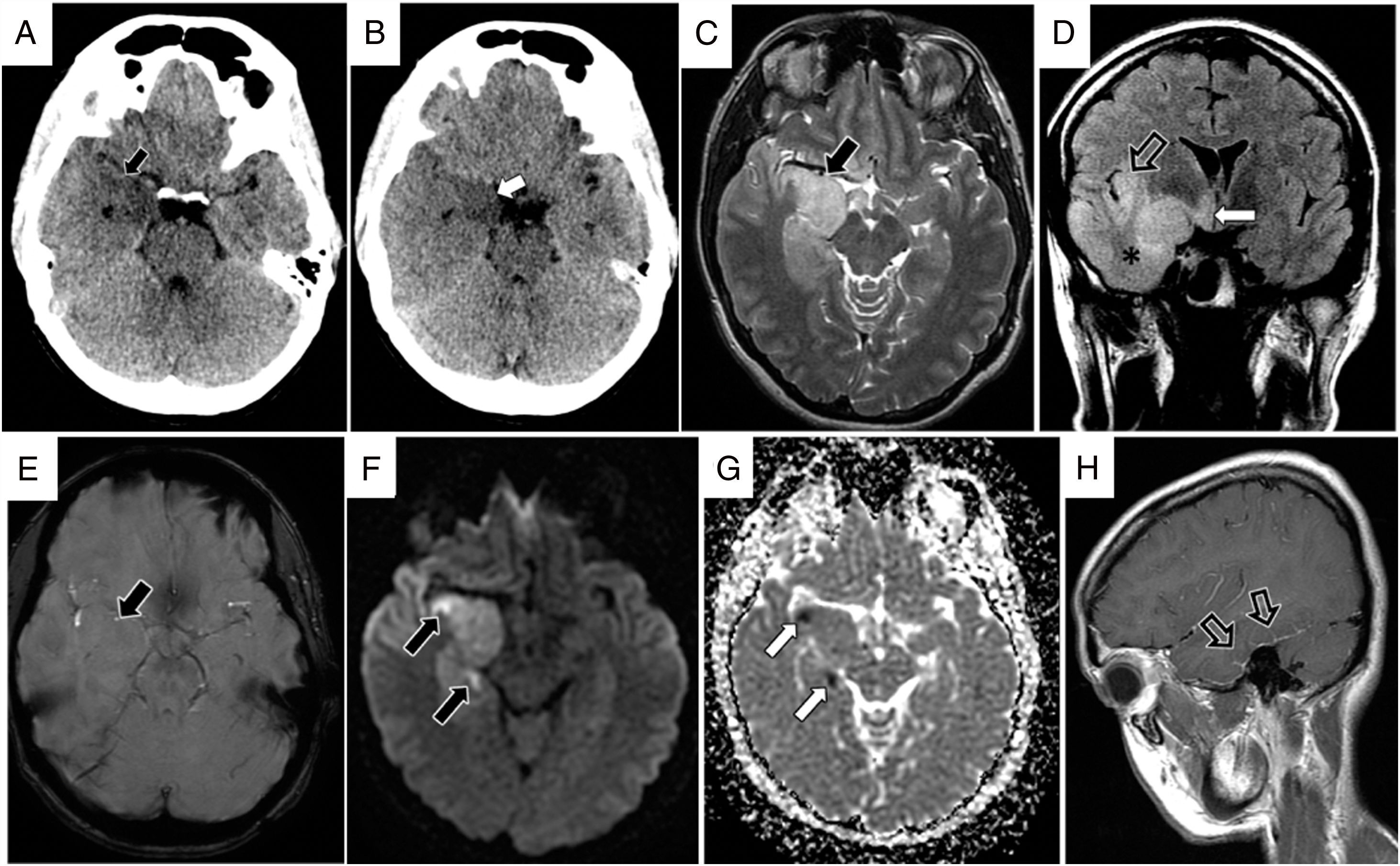

We present the case of a 45-year-old woman with no relevant history who attended the emergency department with headache and fever of 3 days’ progression, and no signs of encephalopathy. The physical examination revealed a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15, with no focal neurological signs. A head CT scan (Fig. 1A) detected hypodensity and tumefaction of the right anterior temporal pole. CSF analysis identified lymphocytosis, and empirical treatment was started with intravenous aciclovir. An MRI scan performed 3 days after symptom onset (Fig. 2) showed involvement of the right temporal lobe and gyrus rectus, with no signs of petechial haemorrhage, and no haemorrhagic foci in other areas. A polymerase chain reaction assay returned positive results for herpes simplex virus 1 in the CSF.

A) and B) Transverse sections from the initial head CT scan, showing findings suggestive of herpes virus encephalitis, with cortico-subcortical hypodensity in the anterior basal area of the right temporal lobe (black arrow). The images also show hypodensity with tumefaction of the amygdala and temporal uncus, resulting in mass effect and uncal herniation (white arrow). C-H) Brain MRI study obtained 3 days after symptom onset showing characteristic signs of herpes simplex encephalitis. C) T2-weighted TSE sequence (transverse plane) showing hyperintensity due to oedema, with tumefaction of the right anteromedial temporal lobe (black arrow) and hippocampus. D) FLAIR sequence (coronal plane) showing extensive cortical tumefaction of the right temporal lobe (asterisk) and extension of the hyperintensity to the right insula (hollow arrow) and hypothalamus (white arrow). E) Susceptibility-weighted imaging sequence (transverse plane) of the area of most intense involvement in the temporal lobe, with no evidence of petechial haemorrhage at 3 days of progression (black arrow). The diffusion sequence (F) and ADC map (G) show extensive right temporal hyperintensity due to the T2 effect, which is more pronounced in the cortex of the lateral gyri, with punctiform hyperintensities on the diffusion-weighted sequence (black arrows), which coincide with areas of diffusion restriction and hypointensity on the ADC map (white arrows). H) Contrast-enhanced, T1-weighted TSE sequence (sagittal plane) showing leptomeningeal contrast uptake in the basal area of the right temporal lobe (hollow arrows).

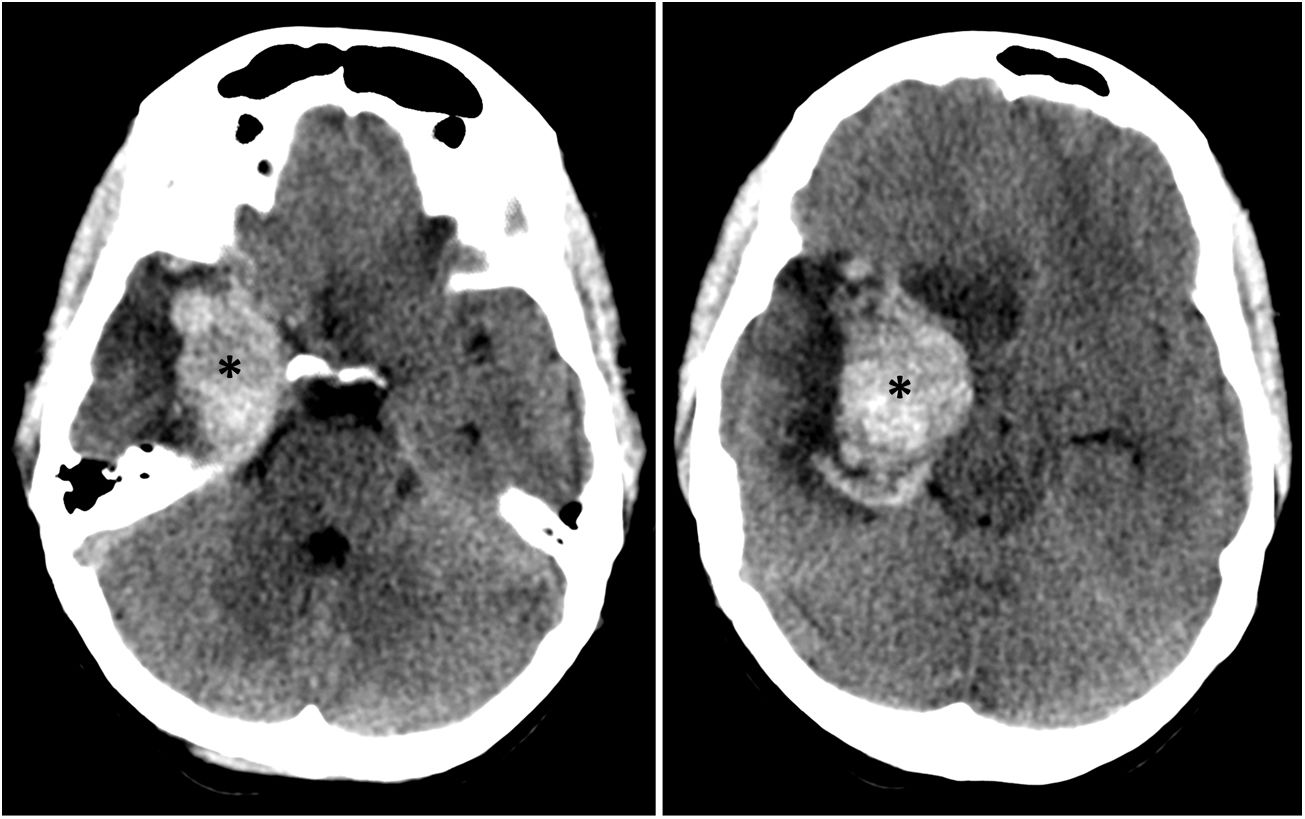

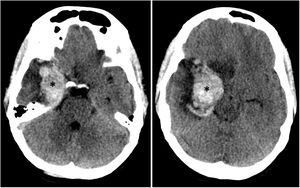

Transverse sequences from the head CT scan performed 10 days after onset, when symptoms worsened. The images are similar to those from the original study, showing a large intraparenchymal haematoma in the right temporal lobe, in the area initially affected by herpes simplex encephalitis (asterisks). The images also show perilesional vasogenic oedema and a considerable mass effect, with effacement of the adjacent sulci and greater herniation of the temporal uncus than in the initial study.

Our patient’s level of consciousness decreased on day 10 after symptom onset, with a score of 10 on the Glasgow Coma Scale. A head CT scan (Fig. 1B) showed an intraparenchymal haemorrhage in the right temporal lobe, measuring 3.6 cm in diameter, surrounded by an area of oedema, and uncal herniation. We administered mannitol and hyperosmolar therapy; the possibility of neurosurgical treatment was considered, but we decided against performing decompressive craniectomy due to a favourable treatment response. Radiological and clinical progression were favourable, with the patient displaying fatigue during activities of daily living a year after the episode.

Imaging studies of herpes simplex encephalitis show unilateral onset in the anteromedial temporal lobe and orbitofrontal gyri, with subsequent asymmetrical bilateral posterior progression.1 Initial CT findings are normal in 25% of patients; the typical finding is cortico-subcortical hypoattenuation with mass effect. MRI is more sensitive for detecting the disease, with T2-weighted sequences showing hyperintensity due to oedema and inflammation; diffusion-weighted sequences may show restriction due to cytotoxic oedema, which is associated with poorer prognosis. Gyral and leptomeningeal contrast enhancement are also common MRI findings.2 As the disease progresses, both tests may detect foci of microbleeds due to petechial haemorrhage.3

Petechial haemorrhages in the cortex and subcortical white matter are typical anatomical pathology and radiology findings. Intraparenchymal haematoma in the affected area is a very rare complication3; a literature review identified 27 cases,3–11 with a mortality rate of 5.2%.3

The aetiology of this complication is unknown. Possible causes suggested in the literature include endothelial damage secondary to small-vessel vasculitis induced by the infection; an immune-mediated inflammatory reaction; and increased intracranial pressure, which peaks at 10–12 days.3

Untreated herpes simplex encephalitis presents a mortality rate of up to 70%, decreasing to 20%–30% with the administration of aciclovir2–4; empirical treatment with intravenous aciclovir at 10 mg/kg/8 h is therefore recommended.12 Given the non-specific nature of the symptoms, the fundamental role of imaging studies during the progression of herpes simplex encephalitis is to optimise therapeutic management in the event that symptoms show no change or worsen, as these techniques enable us to distinguish between treatment resistance, aciclovir-induced toxicity, and haemorrhagic complications.3

If the predominant sign is intracranial hypertension, it is essential to control this through osmotherapy, sedatives, and even barbiturates and other third-line measures.13 The use of systemic corticosteroids is controversial.14 Surgical treatment should be considered if intracranial hypertension is refractory to medical treatment or if imaging findings suggest brainstem compression due to the mass effect of the temporal lobe; however, some reviews have not demonstrated significant differences in long-term outcomes between patients with intraparenchymal haemorrhage receiving medical and surgical treatment.3,15 Treatment decisions should be made on an individual basis, with surgical treatment used as a rescue measure in selected cases.

In conclusion, intraparenchymal haemorrhage is a rare but plausible complication of herpes simplex encephalitis in patients showing no clinical improvement or worsening of symptoms in the weeks after treatment onset. Imaging studies performed immediately after admission enable early diagnosis and optimised management.

Please cite this article as: Veiga Canuto D, Carreres Polo J, Aparici Robles F, Quiroz Tejada A. Hematoma cerebral agudo en la evolución de una encefalitis por virus herpes simple tipo 1. Una complicación infrecuente. Neurología. 2021;36:80–82.