There is evidence of insufficient communication abilities by medical specialists as well as of the limited retentive capacities of patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) and their caregivers. The main reasons for this include the personal limitations of the physician, as well as external, emotional and social-cultural factors associated with the patients and their caregivers.

The aim of this study is to compare the clinical information on AD provided by the physicians and that perceived by caregivers and to assess factors associated with differences in perception.

Patients and methodsWe carried out an observational national multicentre study based on questionnaires assessing the information provided by the physician and that retained by the caregiver for 17 items of information. The study involved 61 researchers and included a total of 679 patients who met the selection criteria. We evaluated the factors associated with the difference in perception of the information that was transmitted.

ResultsParticipating caregivers had a mean age of 57.2±14.8 years, with an average care time of 27.6±28.0 months. Approximately half (50.9%) were children of the AD patient and most lived in the same household (64.9%). Caregivers assigned significantly higher ratings to information on concept of disease, aetiology, pathogenesis, dosage and treatment recommendations and adherence, while doctors assigned significantly higher ratings to information related to demystification and correcting preconceived notions, possible complications, adverse events and/or iatrogenesis, family associations, and emotional/psychological support to caregivers (P<.05). Concordance between the information provided and that received was classified between poor and weak (inter-rater agreement ≤0.27). The degree of disease progression using the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) was a factor significantly associated with professional-carer information discrepancy (P=.002).

ConclusionsMany areas of information showed large differences in perception between physicians and caregivers of AD patients, which highlights the need to improve the communication process in order to achieve higher quality.

Existen evidencias de la insuficiente capacidad informativa por parte de los especialistas médicos, así como de las dificultades retentivas de los pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA) y de sus cuidadores. Entre las diversas causas figuran tanto las limitaciones personales del profesional como los determinantes externos, emocionales y socioculturales del paciente y de su cuidador.

Contrastar la información clínica proporcionada por los médicos sobre la EA y la percibida por los cuidadores y evaluar los factores asociados a las diferencias de percepción.

Pacientes y métodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio observacional, multicéntrico y nacional mediante cuestionarios que evalúan la información suministrada por el médico y la retenida por el paciente en 17 aspectos informativos. Participaron 61 investigadores que incluyeron a un total de 679 pacientes que cumplían los criterios de selección. Se evaluaron los factores asociados a la diferencia de percepción sobre la información transmitida.

ResultadosLos cuidadores participantes tenían una media de 57,2±14,8 años, habiendo dedicado un tiempo medio como cuidadores de 27,6±28,0 meses, y siendo el 50,9% hijos del paciente que mayoritariamente vivían en el mismo domicilio (64,9%). Los cuidadores valoraron significativamente mejor la información recibida sobre: concepto de la enfermedad, aspectos etiopatogénicos, posología y recomendaciones sobre el tratamiento y adherencia terapéutica, mientras que los médicos consideraron significativamente mejor la información referente a desmitificación y corrección de concepciones previas, posibles complicaciones, riesgos, efectos adversos y/o yatrogenia, asociaciones de familiares, y ayuda emocional/psicológica a cuidadores (p<0,05). La concordancia en la información suministrada y la recibida fue entre pobre y débil (Kappa ≤ 0,27). El grado de evolución de la enfermedad (escala GDS) fue un factor significativamente asociado con la discordancia profesional-cuidador (p=0,002).

ConclusionesSe apreciaron diferencias de percepción entre médicos y cuidadores de pacientes con EA para numerosos aspectos informativos, evidenciando la necesidad de mejorar el proceso comunicativo para optimizar su calidad.

As life expectancies increase in developed countries, Alzheimer's disease (AD) is becoming the leading public health problem associated with the ageing population. In Spain, it is estimated that AD has a prevalence of 4.3% and an incidence of 9.5 cases per 1000 individuals per year.1,2 When care is provided by family members living with the patient, the family environment is affected by the stress, unease, and workload associated with the disease.3

Cholinesterase inhibitors have been shown to be specific and useful, and they are therefore used as a first-line treatment, especially during early and middle stages. Several studies have shown that anti-dementia drugs improve or stabilise cognitive, behavioural, and functional disorders linked to AD. They also delay symptom onset and institutionalisation, reduce mortality rate, decrease caregiver burden, and lower healthcare spending. Moreover, they have been shown to modify the clinical course of the disease4–8 by halting its progression for periods of up to 4 years.9 The use of anti-dementia drugs in clinical daily practice is still limited,10 and treatment adherence has a tendency to gradually decrease, especially when other treatments are being used concomitantly.11 These factors have a negative impact on treatment continuity, which is necessary in order to slow the progression of cognitive decline.12,13 According to some studies, 30% of patients undergoing treatment discontinue it during the first 60 days,14 and 14% of the patients who continue treatment for 180 days pass through periods in which treatment is interrupted for as long as 6 weeks.15

Therapeutic compliance in AD largely depends on the patient's caregiver, the information available to that caregiver, his trust in the doctor and his expectations, and his solutions for overcoming the constant challenges of managing the disease. In this context, a patient-focused care approach aims to include the family and the caregiver in decision-making that affects the patient. The caregiver's personal preferences should be considered when choosing among different treatments.

In this participatory approach to healthcare, the caregiver needs high-quality information that is easy to understand and adapted to fit his or her needs. It should include an explanation of the disease, its natural course, and different available treatment options so that the caregiver may make independent and responsible decisions. In many cases, information provided to caregivers has a decisive effect on quality of care, and it is unfairly overlooked in spite of its effect on treatment compliance, patient and caregiver quality of life, and perceived satisfaction with healthcare. Some professionals provide information to patients spontaneously and without prior analysis, often using too many technical terms and allowing their own values to create a bias. As a result, caregivers may perceive the information as excessively cryptic, even though doctors feel that it has been presented properly.

Leaving other more specific communication deficiencies aside, there are several external factors contributing to information being insufficient. They include the patient's and the caregiver's cultural and intellectual levels, language barriers, conditions during the visit, factors affecting the doctor–patient relationship, the caregiver's emotional response to the course of the disease, etc. Therefore, studying and analysing the differences between doctors’ impressions (transmitted information) and AD patient caregivers’ impressions (retained information) may provide objective data to help neurologists reflect on the effectiveness and impact of their messages to the caregiver when diagnosing and treating AD patients.

The main objective of this study is to analyse how effective the neurologist, psychiatrist or geriatrician treating AD patients is at providing information. To this end, we describe differences between the information about the disease and its treatment as intentionally presented by the professional and the information as it is understood by the caregiver. This approach should permit us to evaluate the factors that are usually associated with differences in the way that doctors and caregivers perceive medical information being imparted. It may also identify information on AD that is difficult for caregivers to understand, and areas in which the caregiver's judgment, attitude, or care may need improvement.

Patients and methodsThe current study was carried out by gathering written questionnaires with similar content that were administered simultaneously to doctors and caregivers of AD patients. We then evaluated information provided by the doctor and that retained by the caregiver by using a total of 17 well-defined items of information (Appendix B). Informal caregivers of AD patients were included in the study during a six-month recruiting period, using a consecutive sampling method in neurology, psychiatry, and geriatric medicine departments at different Spanish public health centres providing diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment for AD patients. The criteria employed for AD diagnosis were elaborated by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA).16

Inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: patients diagnosed with AD without sex or age restrictions, and accompanied by their caregivers during a routine or follow-up consultation. Specialist researchers were directly responsible for monitoring patients and providing information to caregivers. All selected patients are typically accompanied by their caregivers during specialist visits, and both patients and caregivers were required to sign an informed consent form.

Following the standard procedure, we selected patients of either sex who had been diagnosed with AD, were accompanied by their respective caregivers, and who had a diagnostic or follow-up appointment with the specialist. Researchers were required to participate directly in the patient's clinical monitoring and in providing information to the caregiver. As stated above, each patient and caregiver had to sign an appropriate informed consent form in order to be included. Caregiver-patient pairs were excluded if caregivers were unable to respond to the study questionnaire due to their educational level or a language barrier.

Two questionnaires were used for every caregiver–patient pair meeting inclusion criteria: one for the medical specialist and the other for the caregiver. Items on the questionnaires are listed below. Immediately after the diagnostic or follow-up consultation with the AD patient, the specialist filled in a questionnaire with 2 different sections. The first was a general section requesting his or her professional opinion about the doctor's role in informing the patient or caregiver (completed only once), and the second section requested a professional opinion about how well he or she had provided information to the caregiver during the diagnostic or follow-up consultation. This second section included the AD patient's medical profile and treatment plan and the survey on the applicability of the information presented to caregivers about the disease and its treatment. After the recruitment visit, the caregiver was interviewed by auxiliary staff members. Meanwhile, caregivers completed their questionnaires, which also contained 2 sections. The first section recorded the caregiver's sociodemographic profile and psychological state, and the second section evaluated the applicability of the information about the disease and its treatment which was presented to the caregiver during the consultation.

The second part of the questionnaire, completed by both researchers and caregivers, included the same 17 well-defined items formulated so as to assess the information presented, the information retained, and differences in perception between the 2 parties. These items refer to the following aspects: (1) concept of the disease, (2) debunking misinformation, (3) aetiopathogenesis, (4) natural history and prognosis of AD, (5) complications and risk situations, (6) genetic and heritable risks, (7) drugs and treatment alternatives, (8) expected treatment responses, (9) risks and adverse effects, (10) drug interactions, (11) treatment perspectives, (12) treatment dosages and recommendations, (13) adherence and risks associated with non-compliance with treatment, (14) anticipated benefits of complementary therapies, 15) social health resources and assistance, (16) family/caregiver associations, and (17) emotional and psychological support.

In order to describe potential differences of opinion between specialists and caregivers regarding each item of information, we calculated for each question the frequency of responses on a scale of 1 to 5 (where 1 indicates “very detailed information” and 5 indicates “very little/no information”) for both the specialist and the caregiver groups. We calculated the average score assigned by each of the groups, in addition to the mean difference between the scores assigned by each group, for each item on the questionnaire. The statistical significance of any differences between the scores provided by each group was determined by performing a contrast hypothesis test for ordinal scales with paired data (Wilcoxon matched pairs/signed ranks test). The level of significance was established at .05.

We calculated Cohen's kappa coefficient and its 95% confidence interval17 as a corrected overall measure of inter-rater agreement for how doctors and caregivers assess information. Both of these groups were considered to be judges assessing the same action (the presentation of information during a clinical consultation). We used the Fleiss–Cohen (quadratic) weights method to calculate the relative importance of disagreements.18 The Bland–Altman method was used to interpret the coefficient (a value of 1 indicates perfect agreement and 0 indicates that the agreement is no better than one obtained by chance).19 All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

ResultsCharacteristics of the researchersThe study included 61 specialist researchers with a mean age (±SD) of 45.9±8.7 years; 62.3% were men. The mean time practising as specialists was 16.6±9.5 years. The most common specialty was neurology (78.7%), followed by geriatric medicine (11.5%) and psychiatry (4.9%). More than half of the professionals (52.6%) provided care through the public system; the most common types of centres were general hospitals (67.2%) and outpatient specialty centres (41.0%). Clinical care was mainly provided by general neurology units (55.7%) and dementia specialist units (29.5%).

Sociodemographic and clinical description of AD patientsWe recruited a total of 679 patients who met all selection criteria. Women accounted for 67.2% of the total and mean age was 77.5±7.0 years. The average amount of time elapsed since the patients were diagnosed was 3.4±2.2 years and their mean MMSE score was 18.1±4.2. Table 1A includes all of the demographic and clinical data.

Sociodemographic and clinical data of the patient (A) and the caregiver (B).

| A) | |

| Patient | |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 456 (67.2) |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 77.5±7.0 |

| Progression timeline for AD (years), mean±SD | 3.4±2.2 |

| Score on MMSE, mean±SD | 18.1±4.2 |

| Stage of progression on GDS, n (%) | |

| GDS-1, no cognitive decline | 2 (0.3) |

| GDS-2, very mild cognitive decline | 13 (2.0) |

| GDS-3, mild cognitive decline | 101 (15.2) |

| GDS-4, moderate cognitive decline | 316 (47.6) |

| GDS-5, moderately severe cognitive decline | 206 (31.0) |

| GDS-6, severe cognitive decline | 24 (3.6) |

| GDS-7, very severe cognitive decline | 7 (0.3) |

| B) | |

| Caregiver | |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 518 (76.3) |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 57.2±14.8 |

| Time spent caring for the patient (months), mean±SD | 27.6±28.0 |

| Relationship to the patient, n (%) | |

| Spouse | 225 (33.4) |

| Son/daughter | 343 (50.9) |

| Other family member | 63 (9.3) |

| Professional caregiver | 30 (4.5) |

| Others | 13 (1.9) |

| Type of domicile, n (%) | |

| Caregiver lives in same household | 437 (64.9) |

| Caregiver does not live in same household (day care) | 197 (29.3) |

| Caregiver does not share the same household (night care) | 19 (2.8) |

| Others | 20 (3.0) |

| Educational level, n (%) | |

| No schooling/illiterate | 14 (2.1) |

| Can read and write | 84 (12.4) |

| Completed primary school | 253 (37.5) |

| Completed secondary school | 179 (26.5) |

| Introductory university studies | 81 (12.0) |

| Advanced university studies | 64 (9.5) |

| HADS scale, mean±SD | |

| Anxiety subscale | 6.8±4.3 |

| Depression subscale | 5.8±4.4 |

| HADS questionnaire,n(%) | |

| Anxiety subscale | |

| No anxiety | 405 (59.6) |

| Possible case of anxiety | 145 (21.4) |

| Probable case of anxiety | 129 (19.0) |

| Depression subscale | |

| No depression | 453 (66.7) |

| Possible case of depression | 130 (19.1) |

| Probable case of depression | 96 (14.1) |

The caregivers of AD patients included in the study had a mean age of 57.2±14.8 years; mean period of time spent taking care of the patient was 27.6±28.0 months. We observed that most of the caregivers lived in the same household as the patient (64.9%) and that most were family members (93.6%).

Table 1B includes additional sociodemographic and clinical information describing the caregivers. It should be noted that 40.4% of the caregivers tested as likely or possible anxiety sufferers. Depression was also prevalent among caregivers, with 33.2% being possible or probable depression sufferers.

Researchers’ and caregivers’ general opinion on information provided during the consultationResearchers listed factors that could potentially facilitate the task of presenting information to caregivers of AD patients. The importance of having enough time during the visit and the educational level of the patient were ranked as the most important factors in the process of providing information. Other important factors listed were absence of language barriers and being sure that information will be received in a positive way. These results are included in Fig. 1.

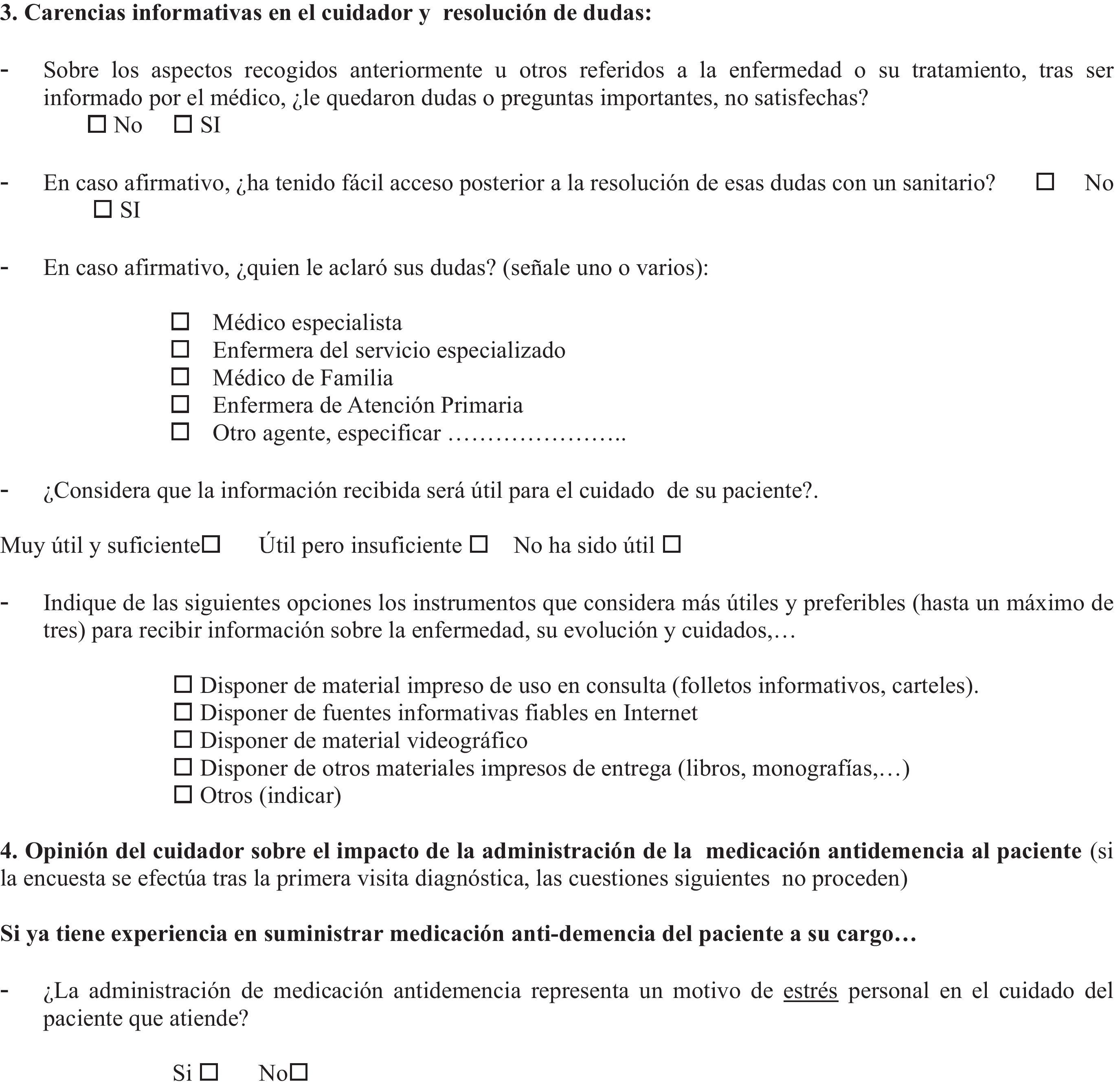

The analysis of caregivers’ opinions regarding their need for information on AD revealed that almost a quarter of the caregivers had important questions that remained unanswered after the doctor had finished presenting information (Fig. 2A). Moreover, in nearly 30% of the cases, the caregiver considered that the information he or she had received was useful, but insufficient (Fig. 2B).

Disagreement between doctors and caregivers about the information provided/receivedWe analysed the 17 items on the questionnaire regarding information provided and received. Items were scored on a scale from 1 to 5 (from more detailed to more limited information). We calculated the means of scores assigned by each of the groups (doctors and caregivers) and identified any significant differences between the 2 groups (Table 2). Fig. 3 is a graph displaying the differences observed between scores given by doctors and by caregivers given to the information provided.

Evaluation of the different opinions of doctors and caregivers about information provided/received, and agreement between groups regarding evaluations.

| Items | Quantity/quality of the information provided regarding... | Doctors (mean)a | Caregivers (mean)a | Pb | Kappa | Concordance |

| 1 | Concept of the disease | 2.3 | 2.1* | .001 | 0.23 | Weak |

| 2 | Debunking myths and correcting preconceived notions | 2.6* | 2.9 | .001 | 0.19 | Poor |

| 3 | Aetiopathogenesis of the disease | 3.1 | 2.8* | .001 | 0.13 | Poor |

| 4 | Natural history of the disease and patient's prognosis (expected clinical progression, new symptoms, etc.) | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0.055 | 0.23 | Weak |

| 5 | Potential complications and risk situations (request for medical assistance, emergency medical attention, etc.) | 2.5* | 2.7 | .001 | 0.26 | Weak |

| 6 | Genetic and heritable risks, possibility of genetic diagnosis, etc. | 3.2 | 3.1 | 0.294 | 0.23 | Weak |

| 7 | Current drugs and treatment alternatives | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.181 | 0.22 | Weak |

| 8 | Expected treatment responses, treatment effectiveness, duration, etc. | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.469 | 0.24 | Weak |

| 9 | Risks/adverse effects/iatrogenesis | 2.4* | 2.6 | .001 | 0.16 | Poor |

| 10 | Potential drug interactions | 2.7* | 2.9 | .001 | 0.21 | Weak |

| 11 | New therapeutic perspectives | 2.9 | 3.0 | 0.179 | 0.21 | Weak |

| 12 | Dosage and recommendations for the prescribed treatment (periodicity, diet, dysphagia, refusal, etc.) | 2.1 | 2.0* | 0.038 | 0.24 | Weak |

| 13 | Importance of treatment adherence and risks associated with treatment non-compliance | 2.3 | 1.9* | .001 | 0.20 | Poor |

| 14 | Expected benefits of complementary treatment (physiotherapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy, cognitive stimulation, etc.) | 2.5 | 2.6 | 0.088 | 0.20 | Poor |

| 15 | Information about the potential social health resources and assistance | 2.7 | 2.8 | 0.294 | 0.21 | Weak |

| 16 | Information about family/caregiver associations | 2.9* | 3.0 | 0.033 | 0.27 | Weak |

| 17 | Information about emotional and psychological support for caregivers | 3.0* | 3.1 | 0.026 | 0.23 | Weak |

Mean calculated from the scores provided by each group (doctors and caregivers) according to the following scale: 1=“very detailed”, 2=“complete”, 3=“basic”, 4=“superficial”, 5=“little or none”.

Mean differences between doctor and caregiver scores regarding information provided during the consultation. The mean and 95% CI are shown for scores. Assessed items: (1) concept of the disease, (2) debunking misinformation, (3) aetiopathogenesis, (4) natural history and prognosis of AD, (5) complications and risk situations, (6) genetic and heritable risks, (7) drugs and treatment alternatives, (8) expected treatment responses, (9) risks and adverse effects, (10) drug interactions, (11) treatment perspectives, (12) dosage and treatment recommendations, (13) adherence and risks associated with non-compliance with treatment, (14) anticipated benefits of complementary therapies, (15) social health resources and assistance, (16) family/caregiver associations, and (17) emotional and psychological support.

Caregivers gave significantly better ratings to information on the concept of the disease, its aetiopathogenesis, drug dosages, and recommendations regarding treatment and treatment adherence (P<.05) On the contrary, medical specialists gave significantly better ratings to aspects such as debunking myths and correcting preconceived notions; possible complications, risks, adverse effects, and/or iatrogenesis; information about family associations; and emotional and psychological support for caregivers (P<.05).

The qualitative assessment of agreement between doctors and caregivers on the subject of information was analysed by calculating the Kappa coefficient for each item of information in the study (a value of 1 indicates perfect agreement and 0 indicates that agreement is no better than might occur by chance). Overall, concordance between doctors and caregivers for the quality/quantity of the information received was weak (Kappa≤0.27) (Table 2). Nevertheless, concordance was clearly poor for some items, such as aetiopathogenesis, risks and adverse effects, debunking misconceptions, treatment adherence, and benefits of complementary treatments.

Factors associated with differing perceptions of informationIn order to identify factors that could contribute to differences of opinion between professionals and caregivers regarding the information provided and that retained, we formulated 17 new derived variables (qualitative and binomial), all permitting dichotomous classification of each item according to the difference between doctors’ and caregivers’ scores; each variable corresponds to one of the items of information under study. These derived variables were divided into two groups: “undervalued by the caregiver” when the caregiver's score for the transmitted information was less favourable than the doctor's (caregiver's score on the original scale is higher than the doctor's score), and “not undervalued by the caregiver” when the caregiver's score for the transmitted information was more favourable than the doctor's (caregiver's score on the original scale was the equal to or lower than the doctor's score).

With the help of the steps listed above, we calculated the percentage of disagreement for variables in the category “undervalued by the caregiver”. These percentage scores were named “doctor–caregiver disagreement”, and were expressed on a scale from 0 to 1 (where 0 indicates no disagreement and 1 indicates maximum disagreement). The mean value in this study was 0.29, indicating a considerable degree of disagreement.

Lastly, we identified any potential links between doctor–caregiver disagreement and characteristics of the caregiver's profile (age, sex, educational level, emotional state, time spent caring for patient, personal relationship and living arrangement with the patient) or of the patient's profile (age, sex, disease progression timeline, GDS (Reisberg) scale stage, score on the MMSE). The most significant result we obtained was that stage of progression (GDS scale) was the sole factor associated with a greater discrepancy between how doctors and caregivers perceived the information that had been provided/retained (P=.002) (Fig. 4).

DiscussionThe results of this study show that there is a significant difference in the way doctors and AD patient caregivers perceive the information which the doctor presents and that which the caregiver assimilates. The main purpose of the initial analysis included in this study was to compare clinical information presented by AD specialists with the information understood and retained by their patients’ caregivers. With this purpose in mind, we aimed to identify the main factors associated with the differences in how information is perceived by doctors and caregivers in order to propose ways to improve communication in the process of caring for patients with Alzheimer's disease.

Prior studies have uncovered differences in how information about illnesses such as Alzheimer's disease is perceived. However, up to now, most of this evidence has been obtained from largely descriptive studies3 that to a certain extent lack a methodology for systematic analysis and are undertaken in order to establish general clinical guidelines for treating patients.20–22

For the first time in Spain, our results allow us to describe the types and categories of information which medical specialists provide and which are most likely to be perceived differently by professionals and AD patients/caregivers. These results provided a more in-depth view of the reasons why caregivers are frequently unable to retain useful instructions intended to promote patient stability and a more favourable course of the disease.

Overall, our study shows that medical specialists need to have more time for consultations with patients. It also reports that the sociocultural characteristics of patients and caregivers (language, educational level, etc.) may hamper their understanding of the information the doctors present. These factors are very well known, not only in the field of AD management, but also in most of the illnesses treated in neurology consultations and specialty centres.23 On the other hand, our study confirms prior results by Kendall et al.24: caregivers of AD patients frequently perceive that the information provided to them does not answer certain important questions. They feel that they do not have enough information, even if they do appreciate any efforts made to keep them informed.

Our study differs from other current studies in that it refers to specific and well-defined areas of information transmitted to caregivers and patients. It lists areas of information that need improvement in order to improve communications between medical specialists and caregivers. This is especially true in the context of a serious illness like Alzheimer's disease, which imposes significant physical, economic and emotional burdens on the caregiver.25

Our study shows that caregivers of AD patients gave a positive rating to information they received regarding the concept of the disease, treatment recommendations, and treatment dosage. In clear contrast to the above, medical specialists were especially satisfied with the information they presented to debunk preconceived notions and warn caregivers about risk situations, and information on family associations, support groups, and similar resources. This obvious disparity in the subjective assessments of the information provided and that received (with poor objective values for concordance) highlights some of the communication problems present in neurology departments when following up on patients with AD. This disparity may also be related to a specific lack associated with treating common dementia problems and providing effective assistance to these patients’ caregivers: there is considerable need for better education and social support if caregivers are to overcome the emotional distress associated with AD, and this need is well-understood in primary care centres.26

Leaving aside the discrepancies identified by the analytical tools used in our study, identifying those factors directly associated with the level of disagreement was problematic. We were only able to link the stage of AD progression to differences in perception of the information presented and that retained. Therefore, for more advanced stages of AD, we observed increased agreement between medical specialists and caregivers regarding information. This association could be related to the benefits of early diagnosis which caregivers report; early diagnosis may facilitate the assimilation, understanding and processing of information about the disease. In addition, it may be helpful in planning future care,27 in spite of the increasing responsibility and burden assumed by the caregiver as the physical and mental state of the AD patient worsens.3

Such a finding calls attention to the importance of a properly integrated approach to providing information on AD. This vision takes into account the three basic pillars of the care process: the medical specialist, the patient, and the caregiver.28 Successfully presenting optimised and correctly selected information that can be retained by the caregiver would result in more efficient care from both the patient and the caregiver perspectives; this in turn would significantly lower the risk of the patient being admitted to a residence29 and lower the social and health costs of caring for the patient.30,31

In conclusion, we should highlight that this study revealed significant discrepancies in the way the 2 groups (medical specialists and caregivers of AD patients) perceive information. For 10 of the 17 areas of information that were assessed, the information presented by the doctors and received by the caregivers was rated differently. The results of the study show that the doctor-patient communication process must be improved in order to optimise the quality and quantity of the information that caregivers effectively receive and retain. In this way, the excellent service they provide to our society will become increasingly efficient and sustainable.

FundingThis study received financial support from Novartis Farmacéutica, S.A.

Conflicts of interestDr. J.L. Molinuevo has received fees as a consultant for the following pharmaceutical companies: Pfizer, Ellan Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Lundbeck, Janssen-Cilag, General Electric, Bayer, and Innogenetics. Dr. B. Hernández is employed by Novartis Farmacéutica, S.A.

We would like to thank Emili González-Pérez (Scientific Department at Trial Form Support, Spain) for his assistance with our study.

TRACE Working Group: Valero Pérez Camo (Unidad de Salud Mental Delicias, Zaragoza), María Concepción Ortiz Domingo (Hospital San Juan de Dios, Zaragoza), Paloma González García (Hospital San José, Teruel), Teresa Calatayud Noguera (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo), Juan Antonio Gil López (Clínica de Neuropsiquiatría, Gijón), José Gutiérrez Rodríguez (Sociosanitaroa Larrañaga, Avilés), Eloy Rodríguez Rodríguez (Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander), Miguel Goñi Imizcoz (Hospital Divino Vallés, Burgos), Javier Ruiz Martinez (Hospital Donostia, San Sebastián), Jorge Aguirre Inchusta (Clínica Padre Menni, Pamplona), Lourdes San Martín Ganuza (La Vaguada, Pamplona), Agustín Urrutia Sanzberro (Centro Hospitalario Benito Menni, Elizondo), José Luís Sánchez Menoyo (Aita Menni Ospitalea, Bilbao), Javier Ruiz Ojeda, Bilbao), José Marey López (Centro Hospital Universitario A Coruña), Juan Carlos Porven Díaz (Hospital San José, Lugo), María Teresa Olcoz Chiva (Hospital Meixoeiro, Vigo), Margarita Vinuela Beneitez, Instituto Carbonell, Palma de Mallorca), Ana María Pujol Nuez (Clínica Juaneda, Palma de Mallorca), Fritz Nobbe (Clonus, Palma de Mallorca), Antonio García Trujillo (Mente, Palma de Mallorca), Cristóbal Díez-Aja López (Clínica Merced, Barcelona), Juan Hermenegildo Catena Mir (Hosptial Sant Andreu, Manresa), Alberto Molins Albanell (Hospital Josep Trueta, Girona), María del Mar Fernández Adarte (Centre Sociosanitari Bernat Jaume, Figueres), María Rosa Cano Castella (EAIA Trastornos Cognitivos, Reus), Jaume Burcet Darde (Hospital del Vendrell, El Vendrell), Ramón Cristofol Allué (Antic Hospital de Sant Jaume, Mataró), Ana Isabel Tercero Uribe (CAP II Cerdanyola, Ripollet), Sonsoles Abaceta Arilla (Parc Taulí, Sabadell), Montserrat Pujol Sabaté (Hospital Santa María, Lleida), Consuelo Almenar Monfort (Benito Menni, Sant Boi de Llobregat), Doménec Gil Saladie (Hospital Sagrat Cor, Martorell), Ramon Reñé Ramírez (Hosptial Bellvitge, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat), David Andrés Pérez Martínez (Hospital Infanta Cristina, Parla), Jerónimo Almajano Martínez (Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid), Julián Benito León (Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid), María de Toledo Heras (Hospital Severo Ochoa, Madrid), Miguel Ángel García Soldevilla (Hospital Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares), Carmen Borrué Fernández (Hospital Infanta Sofía, San Sebastián de los Reyes), Pedro Emilio Bermejo Velasco (Hospital La Paz, Madrid), Pedro Gil Gregorio (Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid), María Sagrario Manzano Palomo (Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid), Jesús Cacho Gutiérrez (Hospital Universitario Salamanca), Camino Sevilla Gómez (Hospital de la Princesa, Madrid), Eloisa Navarro Merino (Centro de Especialidades Vicente Soldevilla, Madrid), Marta Ochoa Mulas (HM Monteprincipe, Boadilla del Monte), Pilar Sánchez Alonso (Hospital Puerta del Hierro, Majadahonda), Beatriz Mondejar Marín and Carlos Marsal Alonso (Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo), José Luís Parrilla Ramírez (Hosptial Infanta Cristina, Badajoz), Ignacio Casado Naranjo (Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara, Cáceres), Martín Zurdo Hernández (Hospital Virgen del Puerto, Plasencia), Juan Miguel Girón Úbeda (Hospital de Jerez, Jerez de la Frontera), Ricardo de la Vega Cotarelo (Hospital Punta de Europa, Algeciras), Juan Carlos Durán Alonso (Geriátrico San Juan Grande, Jerez de la Frontera), María Teresa García López (Clínica Neurológica, Almería), Tomás Ojea Ortega (Hospital Regional Universitario Carlos Haya, Málaga), Manuel Romero Acebal (Clínica Neurológica, Málaga), Vicente Serrano Castro (Hospital Clínico de Málaga), José María Torralba Roses (Personalia Baena, Baena), Eduardo Aguera Morales (Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba), Eva Cuartero Rodríguez (Hospital Valme, Sevilla), Félix Viñuela Fernández (Hospital Virgen Macarena, Sevilla), Manuel Carballo Cordero (Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla), Antonio Alayón Fumero (Centro Neurológico Alayón, Santa Cruz de Tenerife), H. José Bueno Perdomo (Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria, Santa Cruz de Tenerife), Juan Andrés Cárdenas Rodolfo (Hospital General La Palma, Santa Cruz de Tenerife), María Carmen Pérez Vieitez (Hospital Doctor Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria), Joaquín Escudero Torrilla (Centro de Especialidades José María Haro, Valencia), María Dolores Martínez Lozano (Hospital La Magdalena, Castellón), Vicente Tordera Tordera (Unidad de Salud Mental de Xátiva), Antonio Campayo Ibáñez (Hospital Onteniente, Valencia), Esther López Jiménez (Hospital Perpetuo Socorro, Albacete), Inmaculada Feria Vilar (Hospital General Albacete), Inmaculada Abellán Miralles (Hospital San Vicente de Raspeig, Alicante), Jordi Alom Poveda (Hospital General de Elche), Juan Marín Muñoz (Unidad de Demencias Arrixaca, Murcia), Luís Carles Dies (Centro Carles Egea, Murcia), Luís Miguel Cabello Rodríguez (Hospital Naval, Cartagena), Antonio Salvador Aliaga (Hospital Clínico de Valencia), Rosario Muñoz Lacalle (Unidad de Salud Mental Sueca, Alzira).

Please cite this article as: Molinuevo JL, Hernández B. Evaluación de la información suministrada por el médico especialista sobre la enfermedad de Alzheimer y de la retención lograda por los cuidadores del enfermo. Neurología. 2012;27:453–71.

The members of the Group are listed in Appendix 1 at the end of article.