The Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) is widely used for the assessment of verbal episodic memory, mainly in patients with Alzheimer disease. A Spanish-language version of the FCSRT and normative data were developed within the NEURONORMA project. Availability of alternative, equivalent versions is useful for following patients up in clinical settings. This study aimed to develop an alternative version of the original FCSRT (version B) and to study its equivalence to the original Spanish-language test (version A), and its performance in a sample of healthy individuals, in order to develop reference data.

MethodsWe evaluated 232 healthy participants of the NEURONORMA-Plus project, aged between 18 and 90. Thirty-three participants were assessed with both test versions using a counterbalanced design.

ResultsHigh intra-class correlation coefficients (between 0.8 and 0.9) were observed in the equivalence study. While no significant differences in performance were observed in total recall scores, free recall scores were significantly lower for version B.

ConclusionsThese preliminary results suggest that the newly developed FCSRT version B is equivalent to version A in the main variables tested. Further studies are necessary to ensure interchangeability between versions. We provide normative data for the new version.

El test Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) es una prueba de uso extendido para evaluar la memoria episódica verbal, principalmente en el ámbito de la enfermedad de Alzheimer. Existe una versión española de la prueba con datos normativos proveniente del proyecto NEURONORMA.ES. Disponer de versiones alternativas equivalentes de las pruebas resulta útil para el seguimiento de los pacientes en la práctica clínica. El objetivo del presente estudio es ofrecer una versión alternativa a la original, denominada “B”, estudiar su equivalencia con la versión original española (A) y el rendimiento en la misma de una muestra de sujetos para proporcionar datos de referencia.

MétodosSe evaluaron 232 sujetos sanos entre 18 y 90 años en el contexto del proyecto NEURONORMA-Plus. A 33 de ellos se les administraron ambas versiones con un diseño contrabalanceado.

ResultadosEn el estudio de equivalencia se observaron coeficientes de correlación intraclase elevados (entre 0,8 y 0,9) y diferencias no significativas en las variables de recuerdo total. Sin embargo, sí se hallaron diferencias significativas en los ensayos de evocación libre, en los que el rendimiento en la nueva versión fue menor.

ConclusionesLos resultados iniciales sugieren que la versión B del FCSRT aquí presentada resulta equivalente a la versión A en las variables principales de la prueba. Se requieren de futuros estudios para asegurar la total intercambiabilidad entre versiones. Se aportan datos normativos de la versión presentada.

The Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT),1 a widely used measure of verbal episodic memory, was designed to dissociate the different processes involved in the formation of new memories. The test is intended to improve detection of memory alterations typical of Alzheimer disease (AD); these patients have difficulties learning new information due to alterations in the memory consolidation phase.2 To determine whether memory deficits affect the consolidation phase, the test is based on a learning process in which word coding is controlled by inducing deep semantic processing. To this end, the first task of the test requires the patient to classify words into pre-established semantic categories. Category cues are subsequently used to facilitate the recall of items not retrieved by free recall. This method enables physicians to determine whether memory impairment is due to impaired consolidation or to other factors, including inattention during presentation of the words or difficulty retrieving consolidated information by free recall.

In recent years, the FCSRT has become a standard test for evaluating memory in patients with AD and mild cognitive impairment; the International Working Group diagnostic criteria also recommend this test.3 However, as occurs with any neuropsychological test, and particularly those with verbal content, the FCSRT requires linguistic adaptation and standardisation to the Spanish population to be valid in our setting. The FCSRT was adapted to Spanish in collaboration with the test’s author in the context of the NEURONORMA project, based on psycholinguistic criteria; normative data were published for individuals older than 50 years4 and preliminary data for those younger than 50.5 These data have improved the diagnosis and characterisation of memory problems in Spanish-speakers, particularly in the context of AD, although the test is also useful for detecting and evaluating memory impairment in any neurological disease.

In clinical practice, neuropsychological assessment is regularly used to evaluate cognitive function over time. Repeated evaluations are extremely helpful for monitoring patient progression, but do present some limitations. One of these is the so-called “practice effect,” that is “improvements in cognitive test performance due to repeated evaluation with the same or similar test materials.”6 This means that while cognitive function may have not changed since the previous assessment, scores improve when the evaluation is repeated since the patient has learnt how to complete the test more efficiently or remembers the items (if the same test is used). However, not all tasks and cognitive domains are equally vulnerable to the practice effect. For obvious reasons, declarative episodic memory is most affected by the practice effect, given that previous assessments may act as additional learning trials.7 A recent study provides data on the practice effect and one-year reference norms of cognitive change based on follow-up data from the NEURONORMA study.8 At one year, the researchers observed improvements in FCSRT scores (using the same list of words), with an effect size of 0.24 for total recall and 0.40 for the first free recall trial (approximately 1 point in each variable) in patients aged over 50 years. To minimise the impact of the practice effect, some authors propose developing equivalent versions with different lists of items. Alternative versions of the FCSRT have been published in English9 and Italian10; however, no alternative Spanish-language version has been proved to be equivalent to the Spanish-language FCSRT published by the NEURONORMA research group. Our objective was to create an alternative version of the Spanish-language FCSRT (version B), to study its equivalence to the existing Spanish-language version (version A), and to provide normative data on the performance of cognitively healthy individuals.

MethodsThis study uses data gathered from the NEURONORMA-Plus project, the purpose of which is to provide normative data for neuropsychological tests complementary to the original NEURONORMA test battery. Our study analyses data gathered between 2013 and 2015. All patients signed informed consent forms before being included in the study. The study was approved by our hospital’s ethics committee and complies with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The FCSRT consists of a list of 16 written words that the examinee has to memorise. Each word belongs to a different semantic category; the examiner provides category cues to promote deep, controlled information processing. Instructions for administering the test are included in a subsequent section.

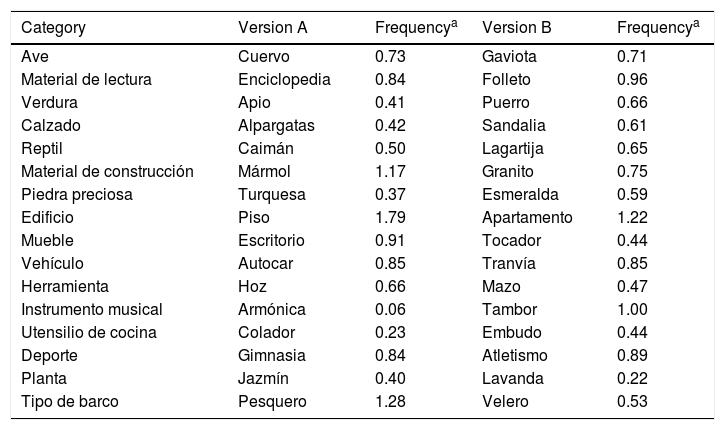

Development of version B of the FCSRTVersion B was created based on the original Spanish-language version of the FCSRT.11 This parallel version used the same semantic categories as version A. In version A, words from each category were chosen based on their lexical frequency according to the study of categories and norms of the Spanish language published in 1994 by Soto et al.12 All words were within the second third of word frequency. The 16 words used in version B were selected based on lexical frequency, prototypicality, and practicality. A basic principle for tests providing category cues is to avoid selecting prototypical words for each category, in order to minimise the number of correct responses given by chance. The word list was created by 2 linguists and 2 clinical researchers specialising in neuropsychology. They first determined updated frequencies of the words included in version A using the Royal Spanish Academy’s Reference Corpus of Contemporary Spanish (CREA, for its Spanish initials: http://web.frl.es/CREA). The researchers then created groups of new words for each semantic category and determined their frequencies to select words with similar frequencies to those included in version A. The analysis of lexical frequency was performed using the subcorpus specific to Spain. Researchers then reached a consensus on which words to include in version B, avoiding polysemic words or those that are difficult to read or pronounce (Table 1).

Lexical frequencies of the words included in versions A and B of the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test.

| Category | Version A | Frequencya | Version B | Frequencya |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ave | Cuervo | 0.73 | Gaviota | 0.71 |

| Material de lectura | Enciclopedia | 0.84 | Folleto | 0.96 |

| Verdura | Apio | 0.41 | Puerro | 0.66 |

| Calzado | Alpargatas | 0.42 | Sandalia | 0.61 |

| Reptil | Caimán | 0.50 | Lagartija | 0.65 |

| Material de construcción | Mármol | 1.17 | Granito | 0.75 |

| Piedra preciosa | Turquesa | 0.37 | Esmeralda | 0.59 |

| Edificio | Piso | 1.79 | Apartamento | 1.22 |

| Mueble | Escritorio | 0.91 | Tocador | 0.44 |

| Vehículo | Autocar | 0.85 | Tranvía | 0.85 |

| Herramienta | Hoz | 0.66 | Mazo | 0.47 |

| Instrumento musical | Armónica | 0.06 | Tambor | 1.00 |

| Utensilio de cocina | Colador | 0.23 | Embudo | 0.44 |

| Deporte | Gimnasia | 0.84 | Atletismo | 0.89 |

| Planta | Jazmín | 0.40 | Lavanda | 0.22 |

| Tipo de barco | Pesquero | 1.28 | Velero | 0.53 |

The test was administered according to the administration instructions, which were adapted from the original instructions11 developed for the NEURONORMA project.13 The task includes 6 different phases: (1) reading and identification of words, (2) interference, (3) free recall, (4) cued recall, (5) selective recall of non-recalled words, and (6) delayed free and cued recall 30minutes later. Phases 2–5 are repeated 3 times during the learning process. The examiner gives the following instructions: “You are going to memorise 16 words. Each word belongs to a different category. I am going to tell you the names of the categories, and I want you to tell me which word belongs to each category. After that, I want you to say as many words as you can remember; it does not matter what order you say them in. When you have finished, I am going to remind you of the categories to help you remember any word that you may have left out. After that, I will tell you any words that you may have forgotten and you will try to memorise them again. You have 3 attempts to memorise all the words.” (1) Reading and identification of words: a card with the first 4 words is placed in front of the examinee, who is asked to read them aloud. The examinee is then provided with the name of each category; he or she must indicate which word belongs to which category. The same procedure is repeated for the remaining 3 cards. If the examinee is unable to identify all categories, the task is interrupted. (2) Interference: after identification, the examinee is asked to perform a serial subtraction task (eg, counting backwards from 100 by serial threes) for 20seconds to prevent subvocal repetition. (3) Free recall: the examinee is asked to say as many words as he or she can remember, in any order, with a time limit of 90seconds. The task is interrupted if the examinee is unable to say any word for 15seconds. Before the second and third free recall trials, the examinee is asked to complete the interference task described above, only changing the starting number (e.g., 99). (4) Cued recall: immediately after each free recall trial, the examinee completes a cued recall task for the items that he or she was unable to recall spontaneously. The examiner provides a category cue for each word the examinee was unable to recall. (5) Selective recall: the examiner provides the items that were not recalled with cues. The selective recall task is only completed in the first 2 trials. (6) Delayed recall: approximately 30minutes (±5) later, the examinee completes another free and cued recall trial. After completing the 3 learning trials, the examinee is informed that he or she will have to recall the words at a later time.

Main variablesData are obtained for 6 variables: free recall trial 1 (FR1; range 0–16), total free recall (TFR; sum of the number of words recalled in all 3 free recall trials; range, 0–48), total recall (TR; sum of the total number of words recalled freely and after cueing in all 3 trials; range, 0–48), delayed free recall (DFR; range, 0–16), total delayed recall (TDR; sum of the number of words recalled freely and after cueing in the delayed recall trial; range, 0–16); and retention index (RI; TDR/total recall in the third trial; range, 0–1). Our study includes data for the first 5 variables.

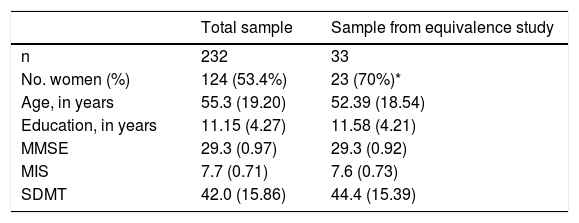

ParticipantsPerformance of healthy individuals: normative sampleIn the context of the NEURONORMA-Plus study, we administered the FCSRT version B to 232 cognitively healthy individuals. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) giving written informed consent, (2) being between 18 and 90 years of age, (3) speaking fluent Spanish and having sufficient ability to read and write, and (4) having no cognitive problems that may affect functional activity in daily life. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) history of central nervous system diseases potentially affecting neuropsychological function (cerebrovascular accidents, epilepsy, meningitis, severe head trauma), (2) history of alcohol or drug abuse, (3) systemic diseases associated with cognitive impairment (based on medical history), (4) history of severe psychiatric disorders (major depression or schizophrenia), (5) hearing or vision problems limiting the individual’s ability to complete the test, (6) psychometric test results indicative of cognitive impairment at the time of inclusion (Mini–Mental State Examination <25 and/or Memory Impairment Screen <5), and (7) any other disorder that may constitute a reason for exclusion in the opinion of the evaluator. We administered the Symbol Digit Modalities Test, which is included in the NEURONORMA test battery, to compare samples. Table 2 shows descriptive data on sociodemographic variables and screening test results.

Descriptive data on sociodemographic variables and screening test results in the total sample and in the subgroup participating in the equivalence study.

| Total sample | Sample from equivalence study | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 232 | 33 |

| No. women (%) | 124 (53.4%) | 23 (70%)* |

| Age, in years | 55.3 (19.20) | 52.39 (18.54) |

| Education, in years | 11.15 (4.27) | 11.58 (4.21) |

| MMSE | 29.3 (0.97) | 29.3 (0.92) |

| MIS | 7.7 (0.71) | 7.6 (0.73) |

| SDMT | 42.0 (15.86) | 44.4 (15.39) |

Data are presented as means (standard deviation), unless otherwise indicated.

MIS: Memory Impairment Screen; MMSE: Mini–Mental State Examination; SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test.

To evaluate the equivalence of versions A and B, we developed a specific protocol according to which a subgroup of 33 members of the sample used for version A was evaluated with both word lists, with a time period of 8 weeks (±1 week) between assessments. We used a counterbalanced measures design, alternating the order in which the 2 versions were administered to avoid any sequence bias; half of the participants completed version A before version B whereas the other half completed version B first.

Statistical analysisWe performed a descriptive study of cognitive and sociodemographic variables; continuous variables are expressed as means (standard deviation) whereas categorical variables are expressed as percentages. The t test and chi-square test were used to evaluate the differences between the total sample and this subgroup. We studied the effect of sociodemographic variables on memory performance using the Pearson correlation coefficient. In the equivalence study subgroup, we calculated the intraclass correlation coefficients between FCSRT variables for both versions of the test and compared means using the paired-samples t test. We also calculated the effect size (Cohen’s d) for the differences between versions. The significance threshold was set at .05. Data were analysed using SPSS, version 22.

Generating normative data for FCSRT version BDue to the differences observed in the equivalence study, we created normative tables for version B, following the NEURONORMA model. The procedure is summarised below. We used the overlapping age group approach,14 in which individuals provide data to more than one norm group. Ten age ranges were established (18-26 years, 27-33, 34-40, 41-47, 48-54, 55-61, 62-68, 69-75, 76-82, and 83-91). For each age group, we created tables of cumulative percentages, to which we assigned NEURONORMA age-adjusted scaled scores (NSSA), ranging from 2 to 18; the data followed a nearly normal distribution, with a mean of 10 (standard deviation, 3). These distributions were used for the linear regression analysis, with years of schooling and sex as predictors to make adjustments where necessary. As with previous analyses of the NEURONORMA project, the sample was split into 2 groups for the linear regression study: individuals younger than 50, and those aged 50 and older. The reason for this division is the difference in education level between young adults and older individuals. We adjusted the scaled scores when the percentage of variation explained by the predictor variable (r2) exceeded 5% and the B coefficient was significant (P<.05). Sex was not found to have a significant effect on any variable according to this criterion. Education, on the contrary, did show an effect. To adjust for education level, we applied the following formulas, using each group’s mean number of years of schooling for adjustment: NSSA&E = NSSA − (B1×[educ − 10]) for individuals aged 50 years and older, and NSSA&E=NSSA − (B2×[educ − 13]) in those younger than 50, with B representing the value of the coefficient obtained in the regression. In all cases, corrections were truncated to the next lowest integer.

ResultsFCSRT version BTable 1 shows both word lists (versions A and B) and the corresponding semantic categories and the base 10 logarithms of the frequency per million words + 1 according to data from the CREA corpus (we added 1 to avoid negative values). Cumulative (A=11.45; B=10.99) and mean frequencies (A=0.72; B=0.69) were similar in both lists, as were the total number of syllables and letters (A: 45 syllables and 113 letters; B: 50 syllables and 116 letters).

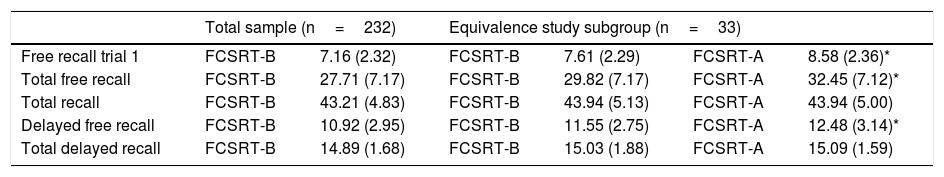

Study in healthy individuals and normative dataTable 2 shows descriptive data from sociodemographic variables and screening tests. It includes data from the total sample and the subgroup of individuals used in the equivalence study. The latter group presented a lower mean age than the total sample, although the difference was not significant (52.4 vs 55.3 years), and included more women (70% vs 53.4%; P<.05). The remaining cognitive and sociodemographic variables showed no significant differences between the total sample and the subgroup used in the equivalence study. FCSRT results are shown in Table 3. In the total sample, the mean total recall score was 43.21, which is equivalent to free or cued recall of 90% of information (maximum score of 48). All variables showed significant negative correlations (P<.05) with age (FR1, r=−0.45; TFR, r=−0.56; TR, r=−0.43; DFR, r=−0.50; TDR, r = −0.36) and positively correlated with education level (FR1, r=0.31; TFR, r=0.39; TR, r=0.32; DFR, r=0.39; TDR, r=0.30). No significant correlations were observed with sex. Normative data tables for each variable are shown in Supplementary Tables S1 to S5; adjustments for education are shown in Supplementary Tables S6 to S11.

Descriptive data for the main variables of the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test version B (FCSRT-B) in the total sample and in the subgroup used for the equivalence study.

| Total sample (n=232) | Equivalence study subgroup (n=33) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free recall trial 1 | FCSRT-B | 7.16 (2.32) | FCSRT-B | 7.61 (2.29) | FCSRT-A | 8.58 (2.36)* |

| Total free recall | FCSRT-B | 27.71 (7.17) | FCSRT-B | 29.82 (7.17) | FCSRT-A | 32.45 (7.12)* |

| Total recall | FCSRT-B | 43.21 (4.83) | FCSRT-B | 43.94 (5.13) | FCSRT-A | 43.94 (5.00) |

| Delayed free recall | FCSRT-B | 10.92 (2.95) | FCSRT-B | 11.55 (2.75) | FCSRT-A | 12.48 (3.14)* |

| Total delayed recall | FCSRT-B | 14.89 (1.68) | FCSRT-B | 15.03 (1.88) | FCSRT-A | 15.09 (1.59) |

Data are presented as means (standard deviation).

Intraclass correlation coefficients for the relationship between both versions of the FCSRT were as follows: TR, 0.89 (95% CI, 0.79-0.94); TFR, 0.82 (95% CI, 0.66-0.91); TDR, 0.75 (95% CI, 0.56-0.87); DFR, 0.8 (95% CI, 0.64-0.90); and FR1, 0.57 (95% CI, 0.29-0.76). In the equivalence study, participants performed better in version A than B for free recall (P<.05). The mean difference between versions was 2.63 words for TFR, 0.97 words for FR1, and 0.93 words for DFR; accounting for the pooled standard deviation, this is equivalent to an effect size (Cohen’s d) of 0.37, 0.42, and 0.32, respectively. However, no significant differences were observed when data for cued recall were included (TR, TDR).

DiscussionWe present an alternative version (version B) to the FCSRT, developed according to psycholinguistic criteria. The new version was administered to a large sample of healthy individuals, some of whom were also evaluated with the original Spanish-language version of the test (NEURONORMA version A) to evaluate equivalence between both versions. As was observed with version A, version B scores were moderately correlated with age and education level. The equivalence study showed differences for free recall but not for cued recall. We provide normative data tables for version B of the test.

Development of version B of the FCSRTWe developed the word list for version B based on lexical frequency, prototypicality, and practicality. Although frequency is an objective means of assessing difficulty recalling a word, this approach is not without limitations. Some values did not coincide with the perceived frequency and difficulty of the words in spoken language. This is probably because frequencies were calculated using the CREA corpus, which is based on written texts only, and the differences between written and spoken language are not accounted for. Other psycholinguistic aspects not considered in our study, such as familiarity or age at language acquisition, may also affect an individual’s ability to recall words. Word length and number of syllables are also relevant factors; both versions of the FCSRT showed similar values overall.

Study in healthy individualsWe studied the performance of 232 healthy individuals in the FCSRT version B, and its correlation with sociodemographic variables. According to our results, older age has a negative effect on test performance, whereas years of schooling are positively correlated with FCSRT scores. Our results are similar to those reported by the NEURONORMA study for FCSRT version A. The sample used for version A (n=517; 340 individuals > 50 years and 177 individuals < 50 years) showed similar performance to that used in version B (FR1: 6.91 [2.63]; TFR: 26.77 [8.05]; TR: 41.59 [5.95]; DFR: 10.30 [3.56]; TDR: 14.37 [2.15]; data not published), supporting the equivalence between versions. Likewise, correlations with sociodemographic variables were similar in both versions, though they were slightly stronger in version A (version A [n=517]; age: FR1, r=−0.57; TFR, r=−0.67; TR, r=−0.55; DFR, r=−0.64; TDR, r=−0.49; education: FR1, r=0.39; TFR, r=0.45; TR, r=0.43; DFR, r=0.42; TDR, r=0.40; data not published).

Equivalence studyThe equivalence study showed high intraclass correlation coefficients (ranging from 0.8 to 0.9) for the main variables. Scores in free recall tasks were significantly higher in version A than in version B. This suggests that free recall of version A items is easier, possibly due to greater familiarity or actual frequencies of the words included (irrespective of CREA data). In diagnosis of AD, the phenomenon showing greatest specificity is the inability to use semantic cues or recognition during memory tasks,15 which is reflected by total recall in the FCSRT; it has been suggested that free recall may be more sensitive in early stages of the disease.16 Version B may be regarded as equivalent to version A in terms of total recall scores after cueing; equivalence is less clear for free recall scores. Our intention for this parallel version was to demonstrate its equivalence to version A, with a view to obtaining normative data that may be applied to either of the 2 versions. However, in view of our results and pending further information on the equivalence of both versions, we provide normative data for FCSRT version B, based on the NEURONORMA methodology (Supplementary Tables S1-S11). To use this data for version A, we recommend adjusting data before conversion to scaled scores (+2 points for TFR and +1 point for DFR). Adjusting scores for different versions of neuropsychological instruments is common practice, especially in such widely used screening test batteries as the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status.17

ConclusionsThis study aimed to develop an alternative version of the Spanish-language FCSRT. According to our results, examinees show poorer performance in free recall tasks in version B. We also provide normative data for the new version. Future studies should include both healthy individuals and patients with memory impairment in order to confirm the equivalence between versions A and B and the usefulness of version B for diagnosing memory problems.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors wish to thank all volunteers who participated in our project. Dr Herman Buschke and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University, New York, hold the copyright to the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test.

Please cite this article as: Grau-Guinea L, et al. Desarrollo, estudio de equivalencia y datos normativos de la versión española B del Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test. Neurología. 2021;36:353–360.