Non-pharmacological treatment of patients with headache, such as dry needling (DN), is associated with less morbidity and mortality and lower costs than pharmacological treatment. Some of these techniques are useful in clinical practice. The aim of this study was to review the level of evidence for DN in patients with headache.

MethodsWe performed a systematic review of randomised clinical trials on headache and DN on the PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and PEDro databases. Methodological quality was evaluated with the Spanish version of the PEDro scale by 2 independent reviewers.

ResultsOf a total of 136 studies, we selected 8 randomised clinical trials published between 1994 and 2019, including a total of 577 patients. Two studies evaluated patients with cervicogenic headache, 2 evaluated patients with tension-type headache, one study assessed patients with migraine, and the remaining 3 evaluated patients with mixed-type headache (tension-type headache/migraine). Quality ratings ranged from low (3/10) to high (7/10). The effectiveness of DN was similar to that of the other interventions. DN was associated with significant improvements in functional and sensory outcomes.

ConclusionsDry needling should be considered for the treatment of headache, and may be applied either alone or in combination with pharmacological treatments.

El uso de tratamientos no farmacológicos en pacientes con cefalea, como la punción seca (PS), está asociado a una baja morbimortalidad y a un bajo coste sanitario. Algunos han demostrado utilidad en la práctica clínica. El objetivo de esta revisión fue analizar el grado de evidencia de la efectividad de la PS en la cefalea.

MétodosRevisión sistemática de ensayos clínicos aleatorizados sobre cefalea y PS en las bases de datos biomédicas PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus y PEDro. Se evaluó la calidad de los estudios incluidos mediante la escala PEDro por 2 evaluadores de forma independiente.

ResultadosDe un total de 136 estudios, se seleccionaron 8 ensayos clínicos publicados entre 1994 y 2019, incluyendo en total 577 pacientes. Dos estudios evaluaron pacientes con cefalea cervicogénica, otros 2, pacientes con cefalea tensional, y otro, pacientes con migraña. Los otros 3 estudios evaluaron pacientes con cefalea de características mixtas (tensional/migraña). La calidad de los estudios incluidos osciló entre «baja» (3/10) y «alta» (8/10). La eficacia de la PS sobre los episodios de cefalea fue similar a la de los tratamientos con los que se comparó. No obstante, obtuvo mejoras significativas respecto a variables funcionales y de sensibilidad.

ConclusionesLa punción seca es una técnica a considerar para el tratamiento de las cefaleas en la consulta, pudiendo utilizarse de forma rutinaria, bien de forma aislada, bien en combinación con terapias farmacológicas.

Headache is the most prevalent neurological disorder, and represents a major healthcare problem worldwide due to the high associated rates of disability.1 In Spain, headache constitutes the most frequent reason for consultation with the neurology department.2–4

Headache management includes pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. The latter include such puncture techniques as acupuncture and dry needling (DN). There is moderate evidence that acupuncture is effective for the prevention of migraine attacks5,6 and for the management of tension-type headache.7 It has therefore been listed as a useful therapy in some clinical practice guidelines, such as those issued by the British Association for the Study of Headache.8 DN is associated with low morbidity and mortality,9 and some studies have demonstrated its cost-effectiveness10; therefore, it would be beneficial to include this technique in clinical practice were there sufficient evidence to support its use. DN is a technique for managing neuromusculoskeletal pain, in which a solid filiform needle with no bevel is inserted into the skin without injection of any substance. It can be applied at various depths: superficial DN stimulates connective tissue, whereas deep DN reaches myofascial trigger points (MTP). MTPs are painful nodules located within a taut band of muscle, whose stimulation produces local and referred pain.11 Superficial DN stimulates sensory afferents, whereas deep DN targets dysfunctional motor endplates.12,13 The main difference between acupuncture and DN is that the former uses standardised points as a reference, whereas the latter targets painful areas and MTPs.14

DN has become increasingly widespread in clinical practice, particularly among physiotherapists specialising in pain management,15,16 and has proven to be effective for the management of myofascial pain in such areas as the trunk and the upper and lower limbs.17,18 However, few studies have evaluated its effectiveness for the management of craniofacial pain.17 A systematic review published in 2014 suggested that DN may be useful in the treatment of headache, although the level of evidence was insufficient to issue a strong recommendation.19

We conducted a systematic review to establish the level of evidence regarding the effectiveness of DN for headache.

Material and methodsStudy designThis systematic review follows the PRISMA recommendations.20 The protocol is registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42019123841).

Eligibility criteriaStudy typesWe only included randomised clinical trials of human patients, published in peer-reviewed journals, in either English or Spanish. We did not limit our search by date of publication or sample size.

Patient characteristicsWe selected studies including patients aged > 18 years old, regardless of sex or geographical location. The study did not take into account the patients’ comorbidities.

Headache characteristicsWe reviewed studies including patients with any type of headache (migraine, tension-type headache, cervicogenic headache, mixed headache, etc), regardless of headache characteristics (aetiology, duration, or frequency). We excluded articles where DN was not used to treat the craniofacial region (eg, neck pain).

Characteristics of outcome variablesWe gathered data on all types of outcome variable, regardless of whether they focused on pain intensity, frequency, or duration, or such beneficial effects as decreased use of pharmacological treatment, decreased pain sensitivity, or improvements in quality of life or mental well-being.

Characteristics of the interventionWe included studies aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of DN. Except where otherwise indicated, the term DN is used in this article to refer exclusively to deep DN. We excluded studies focusing on other techniques for headache management (acupuncture, oral drugs, etc), except when these interventions were compared against or combined with DN. We included studies targeting any craniofacial muscle.

Data searchThe initial search was performed in triplicate, using different devices, by 2 researchers (PBL and VDG). The search was conducted on 7 March 2019, on the following databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and PEDro. We used search terms from 2 categories: terms referring to the intervention (“dry needling” and “dry needle”) and terms referring to the disorder under study (“headache,” “migraine,” and “neuralgia”). These search terms were selected after a preliminary literature search to identify keywords.

The search strategy used on PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus was [(“dry needling” OR “dry needle) AND (headache OR migraine OR neuralgia)], whereas on the PEDro database we performed 6 independent searches, combining pairs of terms from both categories.

To identify additional studies, we reviewed the reference lists of the studies gathered.

Study selectionStudies were selected by 2 independent researchers (DVJ and RYR); any disagreement was resolved by a third researcher (PBL). We read the titles and/or abstracts of the studies gathered, and selected those potentially relevant for the purposes of our study, which were read in full text. The selection criteria were subsequently applied to determine which articles would be included for review.

Data collectionTwo independent researchers (DVJ and PBL) collected data from the selected studies using a standardised data extraction sheet. The following data were gathered: number of participants, headache characteristics, muscles targeted by DN, and comparison group (placebo, acupuncture, drug injection). Data were also gathered on outcome variables related to headache, such as visual analogue scale scores, the headache disability index,21 and a headache index (defined as the product of the mean frequency of headache episodes over one week multiplied by the intensity and/or mean duration of the episodes),22 and outcome variables assessing other benefits of the intervention (neck range of motion, pressure pain threshold, quality of life, etc).

Quality of evidenceTwo researchers (DVJ and RYR) independently evaluated the methodological quality of the selected clinical trials using the PEDro scale23; any disagreements were resolved by a third researcher (PBL). The PEDro scale includes 11 items, scored either 1, when the article meets the criterion, or 0, when it does not. Item 1 evaluates external validity, items 2-9 evaluate internal validity, and items 10 and 11 evaluate the interpretability of results. The maximum possible score is 10 points, as the first item is not counted for the final score. Scores of at least 6 points indicate high methodological quality, scores of 4-5 indicate moderate quality, and scores below 4 points indicate poor quality.

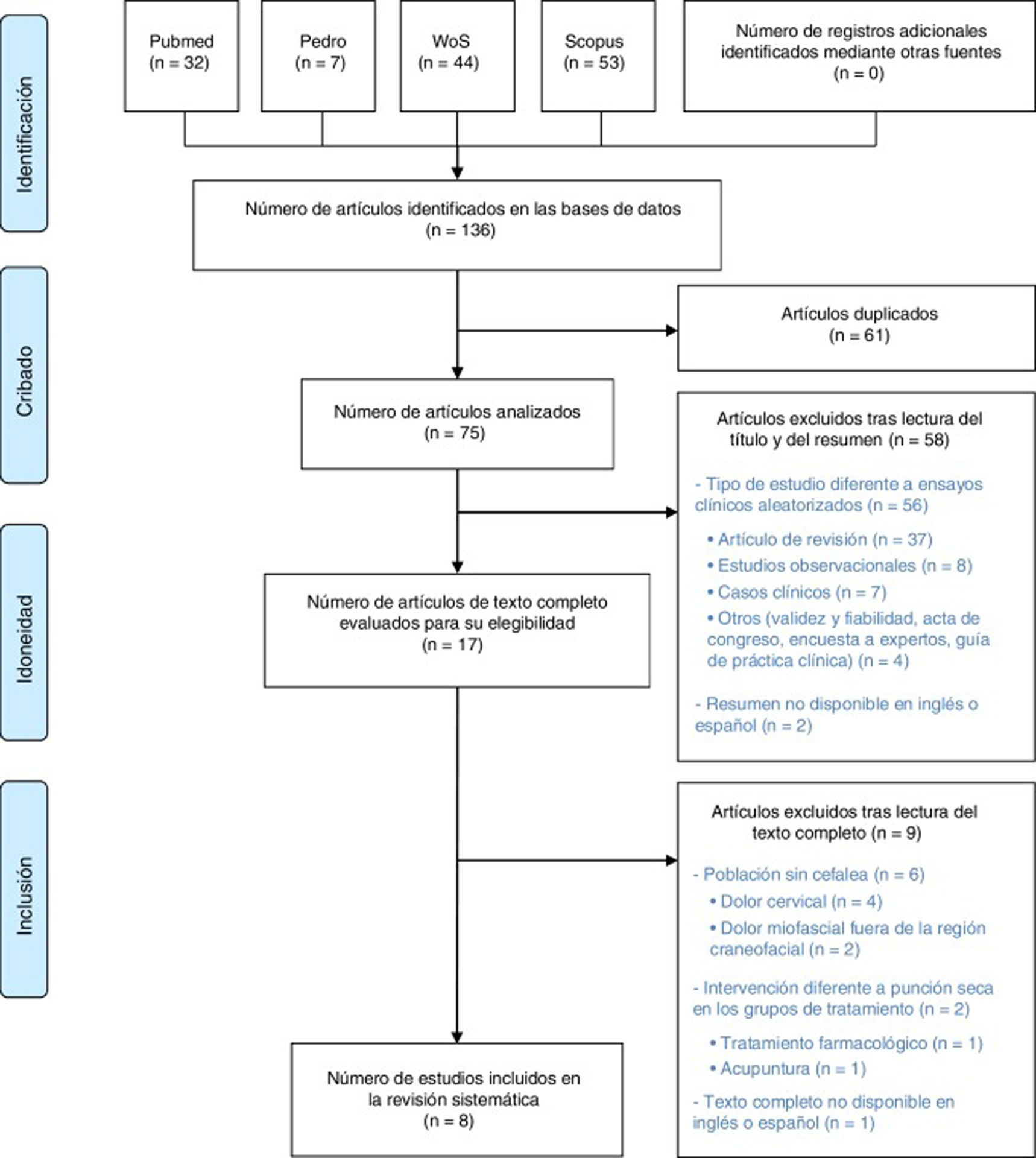

ResultsStudy selectionThe initial literature search yielded a total of 136 studies. After excluding duplicates and screening by title, abstract, and full text using the exclusion criteria mentioned above, a total of 8 studies were included for review. We did not include any additional studies from the reference lists of the studies read in full text. The study selection process is summarised in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of clinical trialsThe main characteristics of the articles included in our review are summarised in Table 1. The reviewed studies were published between 1994 and 2019,24,25 and included a total of 577 patients. The studies with the smallest samples were 2 trials including 30 patients each,24,26 whereas the study with the largest sample included 160 patients.25 Two studies included patients diagnosed with tension-type headache (200 patients in total).25,27 Three studies included patients with headache with mixed characteristics of tension-type headache and migraine (120 patients in total).28–30 Another 2 studies analysed a total of 180 patients with cervicogenic headache.26,31 Only one study exclusively evaluated patients with migraine, with or without aura (77 patients).24 All studies used the definitions of the International Headache Society,32 except for one study,26 which used another classification.33

Studies included in our literature review.

| Author (year) | Type of headache | No. patients (age range, years) | Type of intervention | Muscles treated | Duration of the intervention and timing of assessment | Outcome variables | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gildir et al.25 (2019) | Tension-type headache | 160 (20-50) | G1 (n=80): DN | Not specified (selected according to physical examination findings) | 3 weekly sessions for 2 weeks | VAS, headache index (F×I×D), and quality of life (SF-36) | Decreases in pain frequency, duration, and intensity in both groups. Greater decreases in headache index in G1 at 2 and 4 weeks |

| G2 (n=80): sham acupuncture | Assessment at 2 and 4 weeks post-treatment | ||||||

| Hesse et al.24 (1994) | Migraine with and without aura | 77 (21-70) | G1 (n=38): DN+placebo tablets | Trapezius, rhomboid, and semispinalis capitis | 6- 8 sessions at intervals of 1-3 weeks, for 17 weeks | Frequency, duration, and intensity (headache diary) | Decreases in attack frequency and duration in both groups, with no intergroup differences. No differences in pain intensity |

| G2 (n=39): sham stimulation+metoprolol 100mg/day | |||||||

| Kamali et al.27 (2019) | Tension-type headache | 40 | G1 (n=20): DN | Trapezius, suboccipital, temporalis, and sternocleidomastoid | 3 sessions over 1 week | VAS, pressure pain threshold, headache frequency | Higher pain threshold in G1 than G2 |

| G2 (n=20): manual friction massage | Assessment 48hours after the last session | ||||||

| Karakurum et al.28 (2001) | Headache with mixed characteristics (tension-type headache and migraine) | 30 | G1 (n=15): DN | Trapezius and splenius capitis | 1 weekly session for 4 weeks. Assessment after the 4th session | Headache index (F×I), MTP tenderness, and neck range of motion | Decreases in headache index in both groups, with no intergroup differences. Improvements in MTP tenderness and neck range of motion in G1 |

| G2 (n=15): sham acupuncture | |||||||

| Patra et al.31 (2018) | Cervicogenic headache | 150 (20-50) | G1 (n=50): DN | Trapezius, suboccipital, and paraspinal | Session frequency not specified, treatment for 6 weeks | Headache disability index and pressure pain threshold | Improvements in both variables in all 3 groups, but most marked in G3 |

| G2 (n=50): manual therapy | Assessment at 6 weeks post-treatment | ||||||

| G3 (n=50): DN+manual therapy | |||||||

| Sedighi et al.26 (2017) | Cervicogenic headache | 30 (18-60) | G1 (n=15): DN | Upper trapezius and suboccipital | 1 session. Assessment immediately after treatment and 1 week post-treatment | Headache index (F×I), MTP tenderness, neck range of motion, and functional rating index | Improvements in headache index and MTP tenderness in both groups. Greater improvements in functional rating index and neck range of motion in G1 |

| G2 (n=15): sham acupuncture | |||||||

| Venancio et al.30 (2008) | Headache of mixed characteristics | 45 (18-65) | G1 (n=15): DN | Not specified (selected according to physical examination findings) | 1 session. Assessment immediately after treatment and at 1, 4, and 12 weeks post-treatment | mSSI, local post-injection sensitivity, and use of rescue medication | Improvements in all 3 groups in mSSI at 4 weeks and decreases in the need for rescue medication during the first week. Decreases in local post-injection sensitivity were more marked in G3. |

| G2 (n=15): lidocaine | |||||||

| G3 (n=15): lidocaine+corticoid | |||||||

| Venancio et al.29 (2009) | Headache of mixed characteristics | 45 (18-45) | G1 (n=15): DN | Not specified (selected according to physical examination findings) | 1 session. Assessment immediately after treatment and at 1, 4, and 12 weeks post-treatment | mSSI, local post-injection sensitivity, and use of rescue medication | Improvements in mSSI in all 3 groups at 4 weeks. G2 showed the greatest improvements in local post-injection sensitivity. G3 required less rescue medication during the 12 weeks of follow-up. |

| G2 (n=15): lidocaine | |||||||

| G3 (n=15): botulinum toxin |

D: duration; DN: dry needling; F: frequency; G: group; I: intensity; mSSI: modified Symptom Severity Index; MTP: myofascial trigger point; SF-36: Short Form-36 Health Survey; VAS: visual analogue scale.

The efficacy of the intervention was measured with different tools: the headache index in 3 studies,25,26,28 the headache disability index in one,31 the visual analogue scale in 2,25,27 and the modified Symptom Severity Index in 2.29,30 One study did not clearly specify the methodology used for measuring pain intensity.24 Secondary indices of the effectiveness of the technique were local pressure sensitivity at MTPs, used as an outcome variable in 3 studies,26,29,30 pressure pain threshold in 2 studies,27,31 cervical range of motion in 2,26,28 and quality of life (Short Form-36 Health Survey) in another study.25

All studies reported improvements in pain, regardless of headache characteristics. However, several studies found no significant differences between the intervention group and the control group. Hesse et al.24 found DN to be as effective as metoprolol in reducing the frequency and duration of migraine episodes. Karakurum et al.28 compared DN against sham acupuncture, and Sedighi et al.26 compared deep DN against superficial DN; both research groups reported similar improvements in the headache index scores between groups. However, the study by Sedighi et al.26 did find more marked improvements in cervical range of motion and functional rating index scores in the deep DN group. In a similar study, Venancio et al.29 compared 3 treatments: DN, lidocaine injection, and botulinum toxin injection. All 3 groups showed significant improvements in pain, and only the lidocaine group presented greater improvements in the item assessing local post-injection sensitivity. The same study group had previously published another trial30 comparing 3 groups and using the same selection criteria and outcome variables; the only difference was that group 3 received 0.25% lidocaine plus corticoids, instead of botulinum toxin. Again, all groups showed improvements in the outcome variables, with group 3 showing more marked improvements in terms of local post-injection sensitivity and the need for concomitant treatment. Gildir et al.25 reported improvements in pain frequency, duration, and intensity in patients undergoing DN, and also in patients receiving sham acupuncture. However, improvements in the headache index were more marked in the group treated with DN.

Only 2 studies specify the duration of the intervention. In the patients treated with DN, the needle remained inserted in the MTPs for 20minutes in the study by Gildir et al.25 and for 30minutes in the study by Karakurum et al.28 Likewise, the muscles treated varied between studies, with 3 studies25,29,30 not following a specific protocol, as the muscles treated were selected according to the findings of the physical examination. The remaining 5 studies did use a pre-established protocol to select the muscles to be treated. The trapezius was the only muscle to be treated in all studies; the other muscles varied between studies. The suboccipital muscles were treated in 3 studies.26,27,31

Treatment and follow-up schedules also varied greatly between studies: 3 studies performed a single session of DN,26,29,30 and followed up the patients for variable periods of time (up to 12 weeks in 2 studies29,30 and 4 weeks in the other26). In contrast, 2 studies25,27 performed up to 3 weekly sessions of DN. In the study by Hesse et al.,24 which reported the greatest number of sessions, patients were treated for 17 weeks.

None of the studies reported severe adverse reactions, although some studies did report such mild adverse reactions as nausea,24 pain, or fear.25

Assessment of methodological qualityTable 2 evaluates the methodological quality of the trials included, indicating whether they meet each item of the PEDro scale.

Quality of evidence in the studies included in our review.

| Author (year) | 1a | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total | Methodological quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gildir et al.25 (2019) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 8 | High |

| Hesse et al.24 (1994) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 | High |

| Kamali et al.27 (2019) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 5 | Moderate |

| Karakurum et al.28 (2001) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | 5 | Moderate |

| Patra et al.31 (2018) | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 3 | Low |

| Sedighi et al.26 (2017) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 | High |

| Venancio et al.30 (2008) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 5 | Moderate |

| Venancio et al.29 (2009) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 5 | Moderate |

No: does not meet the criterion; Yes: meets the criterion.

1: eligibility criteria were specified; 2: random allocation; 3: concealed allocation; 4: groups were similar at baseline; 5: blinding of all subjects; 6: blinding of all therapists; 7: blinding of all assessors; 8: follow-up of at least 85% of patients; 9: intention-to-treat analysis; 10: statistical comparisons between groups; 11: point and variability measures for each group.

Three studies had high methodological quality,24–26 with the study by Gildir et al.25 scoring the highest (8 points). Only the study by Patra et al.31 showed poor methodological quality, whereas the remaining studies27–30 had moderate quality (5 points). The mean score of the studies evaluated was 5.5 points. All studies performed statistical comparisons between groups (item 10); none of the therapists involved in any trial was blinded to the treatment (item 6). Only the study by Gildir et al.25 indicated that the group allocation process was concealed (item 3). Participants were blinded (item 5) in the studies by Kamali et al.,27 Karakurum et al.,28 Hesse et al.,24 and Gildir et al.,25 although assessors were only blinded in the latter 3 studies (item 7). Groups were similar at baseline (item 4) in 5 studies.25,26,28–30 Four studies24–26,31 used point measures to reflect differences between groups (item 11).

DiscussionThe studies included in our review showed improvements in patients treated with DN. The methodological quality of the studies ranges from high to low, with half of the studies (4 of 8) presenting moderate quality. None of the studies met the criterion established in item 6 (blinding of all therapists), which underscores the difficulty of blinding therapists to such manual techniques as DN; this has a negative impact on the quality of studies aiming to evaluate the efficacy of the technique.

Four studies compared the effectiveness of DN against that of other non-pharmacological treatments. One of these studies compared DN alone against manual therapy and against DN plus manual therapy, and showed that both DN alone and DN combined with manual therapy effectively improved headache index scores, with the combination of both treatments achieving better results.31 Another study27 compared DN against friction massage over the MTP, reporting decreased pain sensitivity in patients treated with DN. Three studies compared DN against sham acupuncture (subcutaneous needle insertion28) or superficial DN.25,26 According to the results of these studies, subcutaneous needle insertion caused the so-called “needle effect,” relieving pain.34 The deep DN group displayed greater improvements in the headache index in one study,25 and greater improvements in the functional rating index in another study,26 whereas a third study28 reported greater improvements in pain sensitivity and neck range of motion. This suggests that DN has additional benefits compared to other puncture techniques that do not stimulate MTPs.

Two studies compared the effectiveness of DN against that of other therapies involving injection of pharmacological agents,29,30 finding that all patients achieved significant improvements in pain regardless of the treatment received. Only in the case of lidocaine injection was pain less severe after puncture, although this is to be expected given that the injected drug is a local anaesthetic. According to the authors, MTPs must be stimulated and ruptured for pain to be effectively relieved.

Only one trial compared DN against oral pharmacological treatment with migraine prophylactic drugs.24 This study is worth mentioning as it found no statistically significant differences between treatment groups in attack frequency, duration, or intensity.

Regarding the action mechanism of DN, the technique is believed to induce local changes in skeletal muscle35 and pain inhibition at the level of the central nervous system via the periaqueductal grey matter.35–42 Therefore, as is the case with botulinum toxin,43 the analgesic effect of DN may involve both central and peripheral mechanisms.

Our search included studies into headache of different pathophysiologies, given the available evidence of the efficacy of DN for such types of pain as neuralgia.44 However, these studies are case series, as we did not find any clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of DN in patients with neuralgia; therefore, our review does not include studies of these patients. The efficacy of DN for neuralgia should be evaluated in future studies. Needle puncture in itself is known to have analgesic effects; in the case of headache, it remains unclear whether the MTP must be ruptured for the technique to be effective. Although some studies have failed to confirm the superiority of deep DN over superficial DN or sham acupuncture for some variables, we believe that DN should be recommended over other alternatives as it improves pressure pain sensitivity and neck range of motion; this is a diagnostic criterion for cervicogenic headache.45 In any case, few studies have compared both puncture techniques with a view to understanding their clinical effects and the underlying mechanisms.26

Despite the improvements reported by the participants in many of the studies included, the clinical relevance of their results continues to be limited, since improvements in such parameters as the headache index may not translate into an improvement in quality of life. We should therefore be cautious when evaluating the potential benefits of this therapy.

While mild adverse reactions to puncture techniques are frequent,9 patients rarely present such severe adverse reactions as cardiac tamponade,46 pneumothorax, or epidural spinal haematoma.47 However, given the severity of these complications, clinicians trained in the use of puncture needles must be aware of the possibility of these reactions, and appropriate measures must be taken to prevent them. None of the articles included in our study reported severe adverse reactions. However, given the low morbidity and mortality associated with DN as compared to the disability potentially caused by headache, and considering that the studies published to date show that DN is effective, low-risk, and affordable, we believe that this technique may be useful for headache management.

One of the main limitations of our study is the inability to perform a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of methodologies and the highly variable results; this underscores the need to develop specific protocols to increase the reproducibility and comparability of studies into DN. The definition of the headache index is ambiguous; furthermore, the index is not listed among the outcome measures recommended in the International Headache Society’s guidelines for clinical trials.48 Only the visual analogue scale,25,27 diary records of pain intensity,24 and the need for rescue medication29,30 are mentioned in the guidelines. Future clinical trials should also specify the criteria for classifying patients and avoid including patients with headache presenting mixed characteristics. Since our literature search was limited to studies published either in Spanish or in English, it may have omitted relevant studies in other languages. Finally, despite the inability to conduct a meta-analysis, it should be noted that all the studies included in our review reported positive results; future reviews should therefore analyse the possibility of a publication bias.

ConclusionsAlthough much of the available evidence on the effectiveness and safety of DN for the treatment of headache is of moderate quality, this technique should be considered as a treatment option for use either alone or in combination with pharmacological treatments.

FundingPBL received a predoctoral grant (CPB09/18) cofunded by the Regional Government of Aragon and the European Regional Development Fund (Operative Programme “Aragon”). This study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Vázquez-Justes D, Yarzábal-Rodríguez R, Doménech-García V, Herrero P, Bellosta-López P. Análisis de la efectividad de la técnica de punción seca en cefaleas: revisión sistemática. Neurología. 2022;37:806–815.