We present the ophthalmological examination of a patient diagnosed with myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibres (MERRF) syndrome associated with Madelung disease (multiple symmetric lipomatosis), who was a carrier of the T14484C primary mitochondrial mutation, related to Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON).1

Madelung disease is a rare condition (1:25 000) characterised by multiple non-encapsulated lipomas symmetrically distributed around the neck and shoulder girdle.2 It may be associated with other neuropathies, myopathies, or autonomous nervous system involvement.2 Its aetiology is unknown,3 but most cases are associated with alcohol abuse,4 liver transplantation,5 and endocrine or metabolic diseases (diabetes mellitus, hyperuricaemia, and hypercholesterolaemia).6 The m8344A>G mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with MERRF syndrome is present in 10% of the cases.7,8

Clinical caseWe present the case of a 63-year-old woman with no toxic habits who presented neck lipomas secondary to Madelung disease; Wolf–Parkinson–White (WPW) syndrome; and polyneuropathies and myoclonus; her symptoms were already described in an article by López-Blanco et al.1 Her mother presented tremor and lipomas, with the latter also manifesting in the patient’s sister.

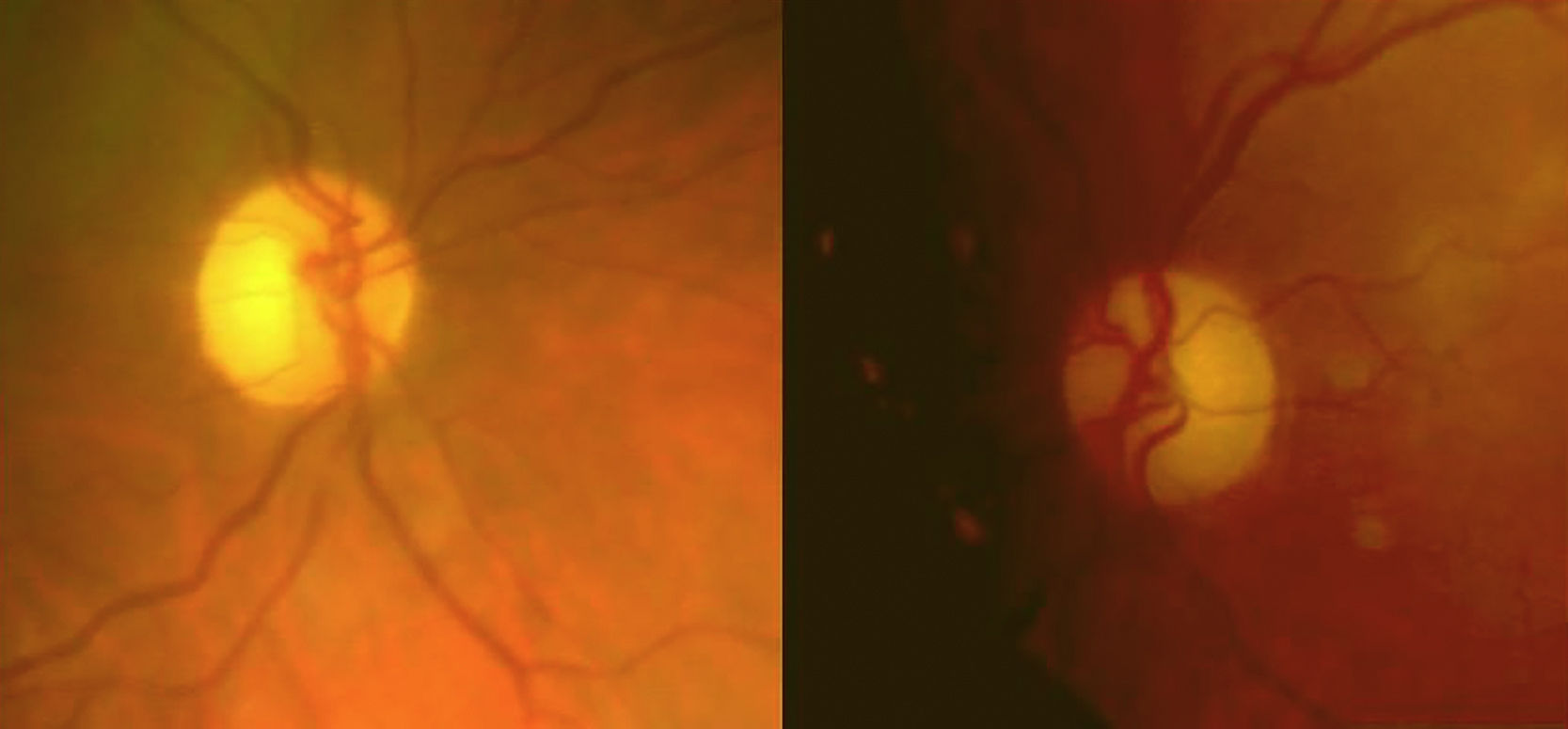

She reported progressive, painless impairment of visual acuity (VA) in the right eye (OD), progressing for one year (VA OD: 0.7; VA OS: 1). We observed bitemporal pallor of both optic nerves (Fig. 1).

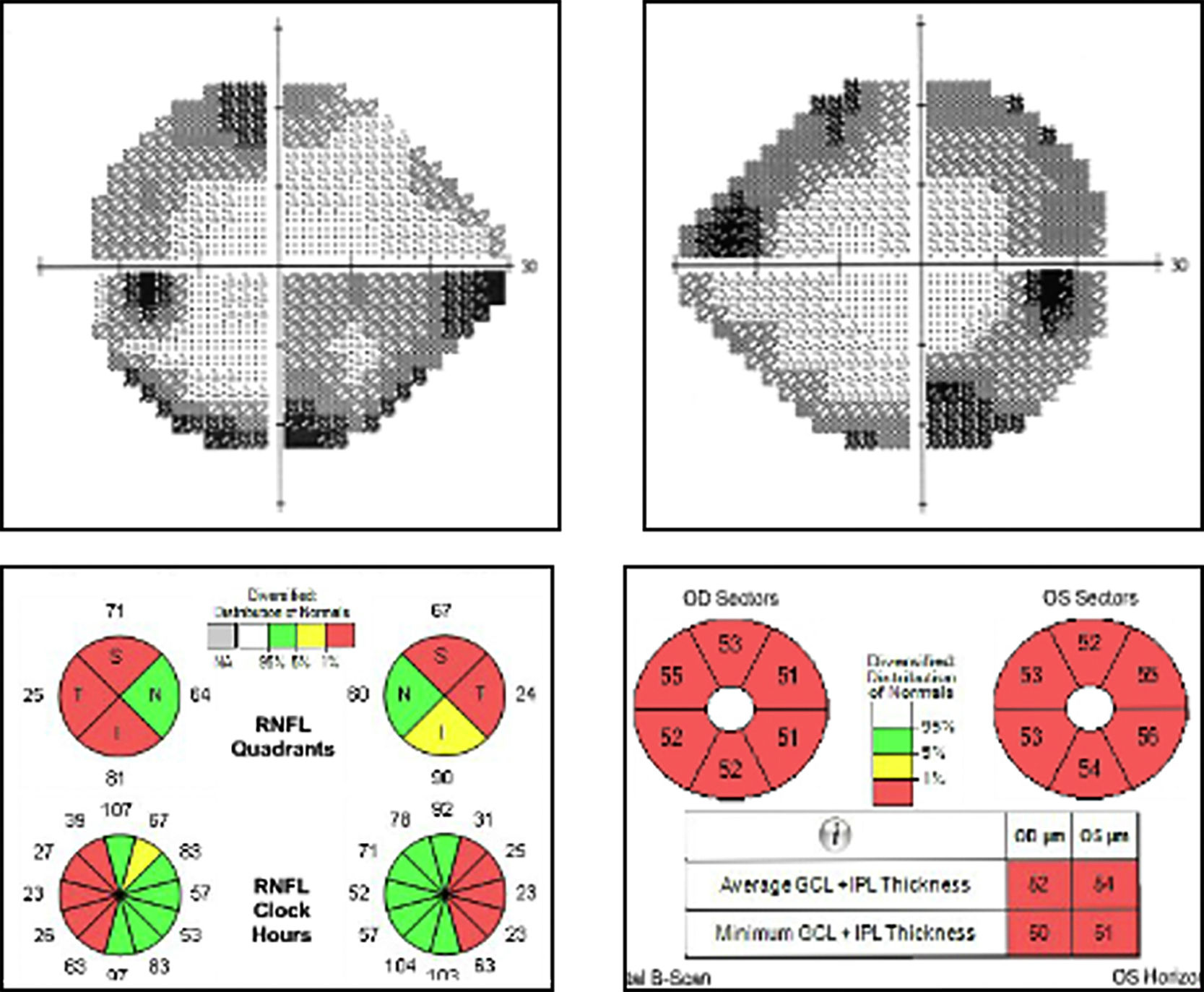

Visual field examination revealed concentric defects in both eyes (OU) and decreased general sensitivity, with no defect in central vision (visual field index and mean defect of 80% and –11.20 dB in OD and 75% and –11.21 dB in OS). The patient was able to distinguish 2 of the 12 plates of the Ishihara test. Optical coherence tomography revealed decreased thickness of the retinal nerve fibre layer, predominantly affecting the temporal region (mean of 60 μm in OU), and a generalised loss of ganglion cells (mean of 52 m in OD and 54 m in OS) (Fig. 2). Results of the multifocal electroretinography (ERG) were normal, and the N95 wave was altered in the pattern ERG.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed supra- and infratentorial atrophy without thickening of the optic nerves in T2-weighted sequences. Electromyography and electrocardiogram results supported the diagnosis of polyneuropathy and WPW syndrome.

Genetic testing showed 2 mitochondrial DNA mutations: m8344A>G and T14484C. A muscle biopsy confirmed presence of ragged red fibres.

Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with MERRF syndrome in addition to Madelung disease, and was a carrier of one of the primary mutations associated with LHON.

We recommended that drugs toxic to the respiratory chain be avoided and that treatment be started with coenzyme Q10.

During follow-up (2 years), visual acuity has been stable.

DiscussionOur patient shows a peculiar overlap of 2 mitochondrial mutations, which affect several organs with high energy demand9 (heart, skeletal muscles, brain, and visual system, particularly the papillomacular bundle).10

Mutations causing MERRF affect mitochondrial respiratory chain function and protein synthesis. Typical features include myoclonus, myelopathy, and spasticity, together with peripheral neuropathies. Patients frequently present short stature and rarely present lipomas. They may also present ataxia, deafness, dementia, and in some cases, epilepsy. Some cases also show optic atrophy and retinopathy.11,12

Bearing in mind that our patient presents 2 mutations potentially responsible for the visual impairment (m8344A>G and T14484C), which each provoke ophthalmological symptoms in 20% of cases, we consider the m8344A>G mutation the main cause of the impairment, and not the mutation associated with LHON, for several reasons: epidemiology (the patient was a woman) and pathochronia (unilateral, progressive vision loss) are not typical of LHON; and the relatively preserved central vision and the visual field defect without central involvement are also not suggestive of LHON.13 The pattern ERG showed an alteration of the N95 wave with normal P50 wave, which suggests altered ganglion cells.14 Optic disc microangiopathy (pseudoedema, hyperaemia, peripapillary telangiectasias, and oedema of the retinal nerve fibre layer) and late-onset optic atrophy are characteristic of LHON; furthermore, the optic nerve may be thickened in T2-weighted magnetic resonance sequences. Our patient’s WPW syndrome may be related to the T14484C mutation.15

Very few cases or families presenting Madelung disease in association with the m8344A>G mutation and MERRF syndrome have been identified, and to our knowledge, no overlap with the T14484C mutation related to LHON1 has been reported; this case shows the best prognosis. In this case, it was not possible to perform genetic testing of family members, as they were not covered by our healthcare district.

In conclusion, we described the ophthalmological manifestations secondary to this overlap of mitochondrial mutations.

Please cite this article as: Gutiérrez-Ortiz C, Rodrigo-Rey S. Neuropatía óptica hereditaria y síndromes sistémicos asociados como resultado del solapamiento de 2 mutaciones mitocondriales. Neurología. 2021;36:472–473.