Since late 2019, and especially during 2020, multiple cases of COVID-19 have been detected in the Chinese city of Wuhan1,2; the disease has become a pandemic particularly affecting China, Southern Europe, and the USA, with very few places in the world escaping its impact.

Spain is one of the countries hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, although geographical differences can be observed. As of 16 April 2020, there are 182816 confirmed cases, 19130 deaths, and 74797 recovered cases, and a slight downward trend has been observed in mortality, use of emergency departments, and intensive care unit admission. The true scale of the pandemic is yet to be determined due to a lack of data on the virus’ global impact on the general population.

This situation has led to the declaration of the state of alarm in Spain,3 with the Ministry of Health being granted a predominant role and healthcare responsibilities remaining within the scope of regional governments,4 which have had to adapt healthcare services to the pandemic and probably reduce the level of care provision for the more specific pathologies of each specialty.

Current data suggest that SARS-CoV-2 is highly contagious. Among the clinical manifestations of COVID-19 (there appear to be a large number of asymptomatic/oligosymptomatic patients),5 the main symptoms include fever, non-productive cough, dyspnoea, pulmonary infiltrates, and lymphocytopaenia. The disease particularly affects elderly and immunosuppressed individuals.

The most frequent neurological manifestations include anosmia and dysgeusia, as well as myalgia, fatigue, and headache; only limited data are available on central and peripheral nervous system involvement. Anecdotal reports of these types of symptoms are beginning to appear, and databases are being generated, as we lack data from researchers with more experience, such as Chinese professionals. According to Dr Robert Stevens, “we know almost nothing about the potential interactions between COVID-19 and the nervous system.”

Despite the increasing number of anecdotal cases and observational data on neurological symptoms, most COVID-19 patients do not present these symptoms, and while neurological alterations are infrequent, they remain a possibility. In addition to the symptoms mentioned above, impaired consciousness, encephalitis, ataxia, Guillain-Barré syndrome,6 acute necrotising encephalitis,7 trigeminal neuralgia, involvement of the medullary respiratory centre, myelitis, and an increased number of cerebrovascular complications have been reported in the literature, for example in the Chinese study of 221 patients from Wuhan. This study describes 11 cases of ischaemic stroke, one of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and one of cerebral haemorrhage; these complications seem to be more frequent among older patients and those with more severe COVID-19. The growing number of anecdotal cases and data from multi-centre databases will probably soon assist in determining the degree of nervous system involvement in COVID-19.

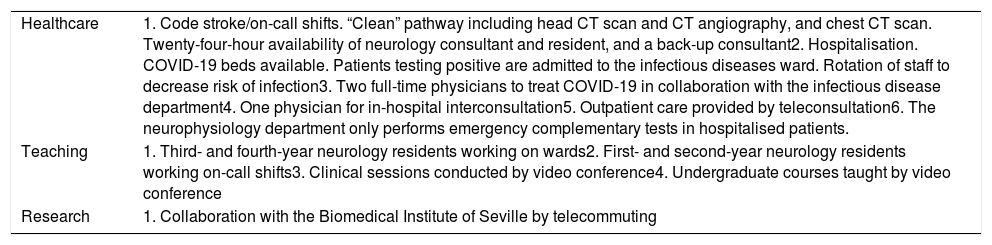

Considering this unprecedented, emergent situation,8 how do neurology departments adapt to respond to the pandemic and continue providing neurological care?9 We would like to highlight the experience of the clinical neurology and neurophysiology unit at our centre, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Seville (Spain) (Table 1).

Organisation of the neurology and neurophysiology unit at Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío.

| Healthcare | 1. Code stroke/on-call shifts. “Clean” pathway including head CT scan and CT angiography, and chest CT scan. Twenty-four-hour availability of neurology consultant and resident, and a back-up consultant2. Hospitalisation. COVID-19 beds available. Patients testing positive are admitted to the infectious diseases ward. Rotation of staff to decrease risk of infection3. Two full-time physicians to treat COVID-19 in collaboration with the infectious disease department4. One physician for in-hospital interconsultation5. Outpatient care provided by teleconsultation6. The neurophysiology department only performs emergency complementary tests in hospitalised patients. |

| Teaching | 1. Third- and fourth-year neurology residents working on wards2. First- and second-year neurology residents working on-call shifts3. Clinical sessions conducted by video conference4. Undergraduate courses taught by video conference |

| Research | 1. Collaboration with the Biomedical Institute of Seville by telecommuting |

COVID-19, which mainly causes respiratory symptoms but can also affect the nervous system, is included in the group of neurosystemic diseases. Our department has a neurosystemic disease unit, which for more than 3 years has provided care to patients with neurological symptoms in the context of complex and emergent diseases. SARS-CoV-2 infection is one of the conditions whose diagnosis and treatment should involve neurologists to improve patients’ prognosis.10 Therefore, the neurosystemic disease unit participates in interpreting and managing infectious diseases. In the earliest published series,11 at least one-third of patients presented neurological manifestations, even with few or no respiratory symptoms at onset. Neurological symptoms are generally due to infection of the olfactory bulb epithelium, either via retrograde synaptic transmission from nerve terminals, or through the haematogenous route, in which the virus damages the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor and crosses the blood-brain barrier. However, neurological complications have typically been observed in more severe cases, older patients, and those with other such comorbidities as arterial hypertension, but are not directly attributed to these. Approximately 10% of patients presented stroke due to complications of late prothrombotic state or in association with the ACE2 receptor targeted by SARS-CoV-2, present in the vascular endothelium; encephalopathy associated with the ACE2 receptor present in glial cells and neurons12; the effects of a “cytokine storm” resembling that observed in immunological reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; or such muscle symptoms as rhabdomyolysis in tissues especially rich in ACE2 receptors. Secondary neurological complications such as those derived from hypoxaemia also require detailed evaluation. Other betacoronaviruses, such as SARS-CoV, caused primary apnoea due to direct viral infection of the medulla and the pons13,14; SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 share more than 74% of antigenic characteristics. Finally, we should mention that several authors, some working near the origin of the pandemic, have highlighted the need to identify and record neurological symptoms in order to prioritise diagnosis of the affected organ and administer adequate treatment to improve prognosis.

This new, emergent pandemic is a challenge for all, and especially for healthcare professionals and specifically neurologists, and our departments must adapt to offer the best possible care. As has previously occurred with neurological complications caused by HIV infection and other infectious pathologies of the central nervous system, neurologists have assisted in the diagnosis and treatment of these patients. This is and will continue to be our task; in the COVID-19 pandemic, in which the characteristics and magnitude of neurological manifestations are yet to be defined, neurologists play a fundamental role, which emphasises the work of such departments as our neurosystemic disease unit. These enable us to improve health outcomes and expand our knowledge of pathologies that present neurological manifestations despite occurring outside the nervous system; through the work of our unit, we are gaining experience in the management of these diseases. In the near future, neurology departments will probably need to reorganise and establish this type of unit, which through the response to the pandemic will equip us to react early and expand the field of neurology.

Please cite this article as: Hernández Ramos FJ, Palomino García A, Jiménez Hernández MD. Neurología ante la pandemia. ¿Está el COVID-19 cambiando la organización de los servicios de neurología? Neurología. 2020;35:269–271.