Retrograde venous air embolism (RVAE) occurs when central venous pressure (CVP) is lower than atmospheric pressure, as is the case with deep inhalation, vertical positions above 45°, and hypovolaemia. The pressure gradient favours the entry of air into venous circulation, travelling to the right ventricle and pulmonary artery, and potentially even leading to an obstructive shock and right ventricular dysfunction.1,2 Some studies show that the air may retrogradely ascend to the cerebral venous circulation when the patient is in a vertical position, due to the lower specific weight of air in comparison with blood. This phenomenon will depend on the size of the bubble, the diameter of the vein, and the patient’s cardiac output.3,4 Causes of RVAE include trauma, vascular surgery, diving, barotrauma due to mechanical ventilation, and insertion and extraction of central venous catheters. Incidence is difficult to determine, ranging from 1.6% to 55.3%; it is an underestimated entity due to the difficulty of establishing a diagnosis, which requires presence of a known risk factor, compatible clinical signs, no right-to-left shunting in the echocardiography, and imaging studies showing the presence of air in the intravascular space. The most frequent neurological complications are altered level of consciousness, coma, stroke, and seizures.5 Patients may also present haemodynamic and respiratory alterations including dyspnoea, tachypnoea, chest pain, arterial hypotension, low cardiac output, and even obstructive shock and cardiorespiratory arrest. Electrocardiographic alterations include sinus tachycardia, right ventricular overload signs, non-specific changes in the ST segment/T-wave, and elevated markers of myocardial damage. Definitive diagnosis is established by head CT scan revealing air bubbles in the cerebral intravascular space and parenchyma, sometimes accompanied by diffuse cerebral oedema. In addition to symptomatic treatment with volume therapy, treatment for RVAE includes vasoactive amines, antiepileptics, oxygen therapy with high FiO2, and placing the patient in the left lateral decubitus position (Durant manoeuvre) or the Trendelenburg position. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy may be considered in severe cases.6

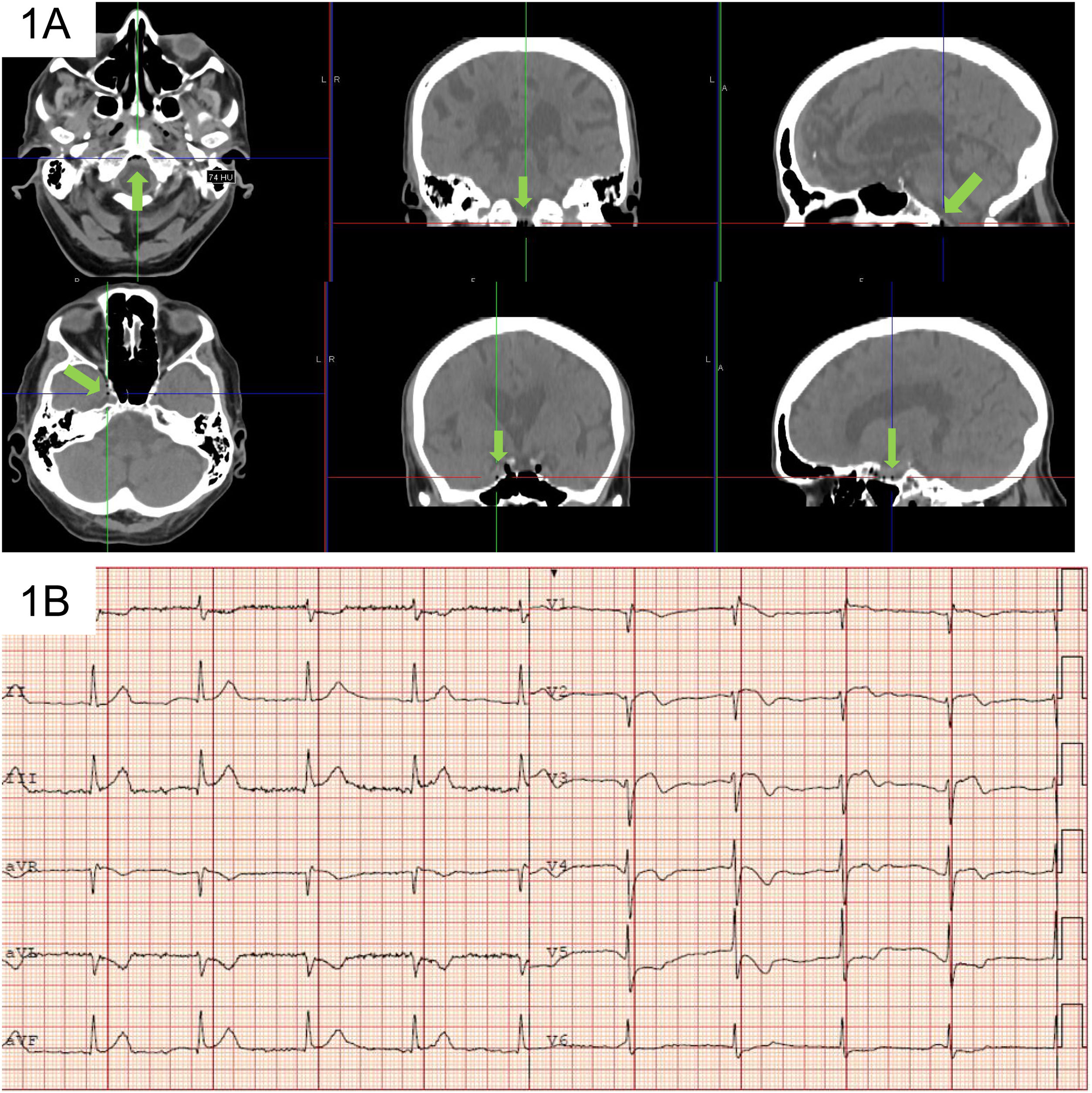

Patient 1Our first patient was a 77-year-old man who was admitted due to perforated sigmoid diverticulitis. The patient had a central venous catheter in the right jugular vein, which was removed with the patient in a seated position. Immediately after removal, he presented arterial hypotension and decreased level of consciousness with spontaneous opening of the eyes, fixed gaze and inability to follow commands, and pain with left hemiparesis. A head CT scan revealed air bubbles in the cavernous sinuses and basal cisterns but no other alterations (Fig. 1A). An electrocardiography (ECG) study showed ST-segment elevation in precordial leads and negative T-wave in leads V5, V6, I, and aVL (Fig. 1B), with elevated markers of myocardial damage. He was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) a few hours late due to a generalised tonic-clonic seizure; we ruled out toxic, metabolic, and infectious aetiology. A transthoracic echocardiography study showed no atrial septal defect. We started treatment with fluid replacement, oxygen therapy using a high-flow mask, and antiepileptics, which led to favourable progression. At 24 hours, ECG findings normalised, myocardial enzyme levels decreased, and a follow-up head CT study confirmed reabsorption of the air bubbles. The patient was discharged from the ICU at 72 hours, presenting normal results in the neurological examination. He was diagnosed with retrograde venous air embolism after removal of the central venous catheter.

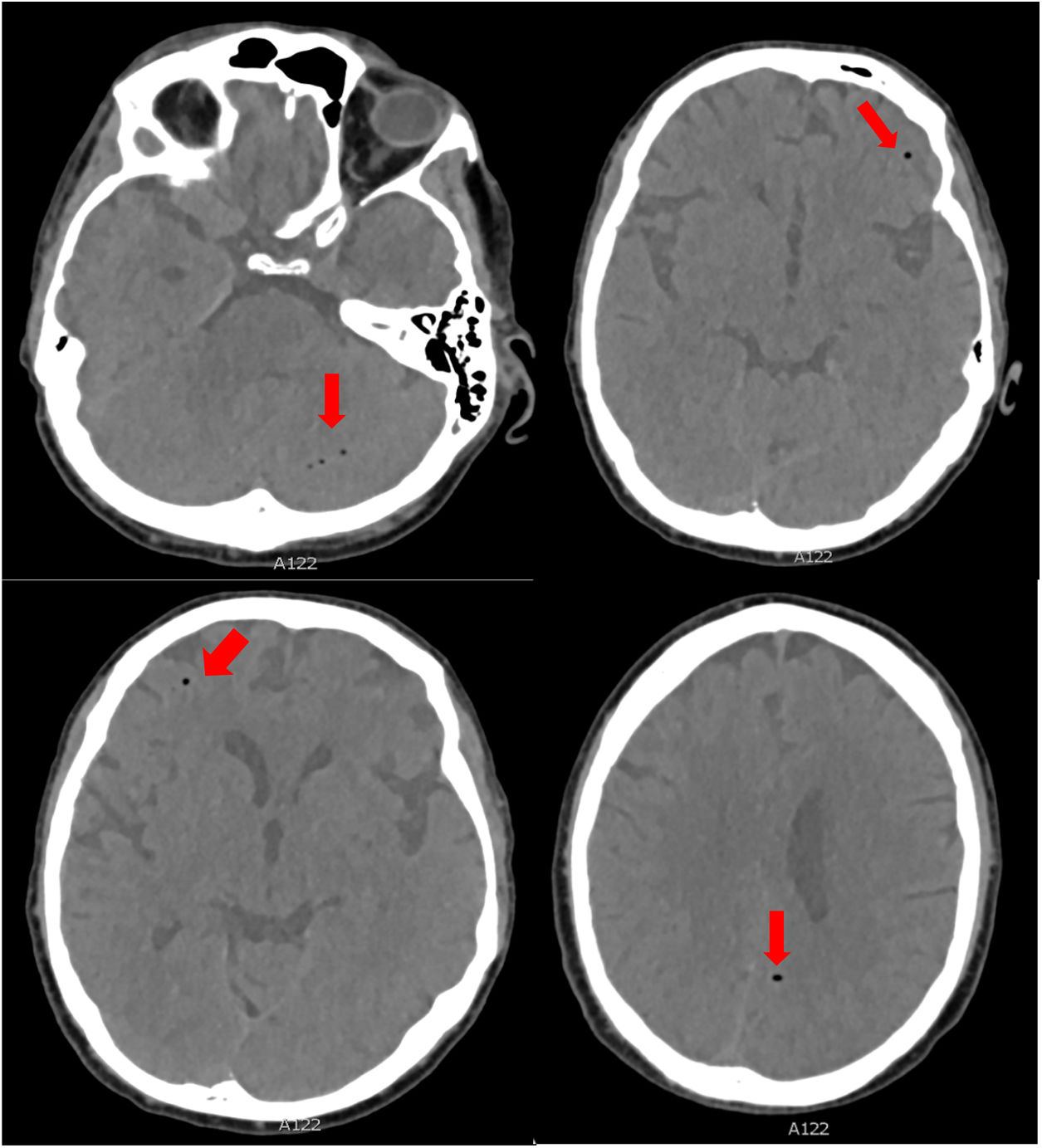

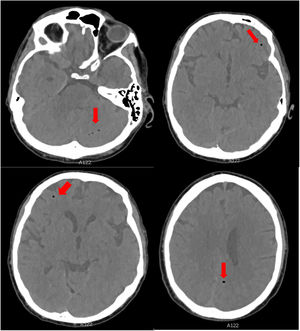

Patient 2The second patient is a 50-year-old man who was admitted to the ICU due to community-acquired bilateral pneumonia. A central venous catheter had been placed in the right subclavian vein and was accidentally removed with the patient standing. His level of consciousness immediately decreased. The neurological examination revealed spontaneous opening of the eyes, with right gaze deviation and decorticate posturing of the upper limbs in response to painful stimuli. We performed orotracheal intubation and started mechanical ventilation. A head CT scan revealed multiple air bubbles in the bilateral frontal and parietal lobes, the left temporal lobe, left cerebellar hemisphere, and both pterygopalatine fossae; these images are compatible with air embolism (Fig. 2). The patient was treated with oxygen therapy in a hyperbaric chamber. During treatment, he presented tonic-clonic seizures, initially affecting the right upper limb and with subsequent generalisation to the upper hemibody. He was placed under deep sedation for 3 days and received antiepileptics. A follow-up CT scan showed reabsorption of the air bubbles. After discontinuation of sedation, he presented a good level of consciousness with no neurological alterations; clinical progression after extubation was good.

Because RVAE can occur as a result of procedures carried out in nearly all medical specialities, it is important that clinicians remain alert and informed regarding this atypical complication. These 2 clinical cases remind us that, to avoid retrograde air embolism, central venous catheters should always be removed with the patient in a horizontal position.

Author contributionsSalvador Balboa and Dolores Escudero participated in data collection and drafted the manuscript. Rodrigo Albillos and Raquel Yano participated in data collection.

FundingThis study has received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.