Knowledge of the socioeconomic impact of dementia-related disorders is essential for appropriate management of healthcare resources and for raising social awareness.

MethodsWe performed a literature review of the published evidence on the epidemiology, morbidity, mortality, associated disability and dependence, and economic impact of dementia and Alzheimer disease (AD) in Spain.

ConclusionsMost population studies of patients older than 65 report prevalence rates ranging from 4% to 9%. Prevalence of dementia and AD is higher in women for nearly every age group. AD is the most common cause of dementia (50%-70% of all cases). Dementia is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, disability, and dependence, and results in a considerable decrease in quality of life and survival. Around 80% of all patients with dementia are cared for by their families, which cover a mean of 87% of the total economic cost, resulting in considerable economic and health burden on caregivers and loss of quality of life. The economic impact of dementia is huge and difficult to evaluate due to the combination of direct and indirect costs. More comprehensive programmes should be developed and resources dedicated to research, prevention, early diagnosis, multidimensional treatment, and multidisciplinary management of these patients in order to reduce the health, social, and economic burden of dementia.

El conocimiento del alcance socioeconómico de las enfermedades que cursan con demencia es esencial para la planificación de recursos y la concienciación social.

DesarrolloSe ha realizado una revisión de los datos publicados hasta el momento sobre la epidemiología, morbilidad, mortalidad, discapacidad, dependencia e impacto económico de la demencia y la enfermedad de Alzheimer en España.

ConclusionesLa mayoría de estudios en población mayor de 65 años estiman una prevalencia entre el 4% y el 9%. La prevalencia es mayor en mujeres en casi todos los grupos de edad. La enfermedad de Alzheimer es la causa de demencia más frecuente (50-70% del total). La demencia provoca un aumento de la morbilidad, mortalidad, discapacidad y dependencia de los pacientes, con una importante disminución de la calidad de vida y la supervivencia. El 80% de los enfermos es cuidado por sus familias, que asumen de media el 87% del coste total, con la consiguiente sobrecarga y menoscabo de la salud y calidad de vida de los cuidadores. El impacto económico de la demencia es enorme, y de evaluación compleja, por la mezcla de costes sanitarios y no sanitarios, directos e indirectos. Es necesario desarrollar programas globales e incrementar los recursos enfocados a fomentar la investigación, prevención, diagnóstico precoz, tratamiento multidimensional y abordaje multidisciplinario, que permitan reducir la carga sanitaria, social y económica de la demencia.

Dementia is a clinical syndrome characterised by acquired, persistent impairment of higher brain functions (memory, language, orientation, calculation, spatial perception, etc.). This results in the patient's loss of independence and has a negative impact on their professional and social life and leisure activities.

Until relatively recently, little attention had been paid to dementia, with only 3 studies on the condition in 1935 and 25 in 1950. Research on dementia has increased exponentially over the past 20 years, with over 90000 studies in 2007 and 170000 at the beginning of 2017. This reflects greater social interest in and increasing awareness of dementia. Few governments considered the condition a healthcare priority until several years ago, when the World Health Organization (WHO) drafted an action plan on the public health response to Alzheimer disease and other types of dementia.1,2

The incidence of dementia increases exponentially with age; a true worldwide epidemic is therefore to be expected in the coming years as a result of population ageing. Statistical evidence shows that dementia is the main cause of disability and dependence in elderly patients, considerably increasing morbidity and mortality. This results in enormous economic, social, and healthcare costs, which fall mainly on patients’ families.

This report analyses the healthcare, social, and economic impact of Alzheimer disease and other types of dementia at a national and international level.

EpidemiologyNearly all studies agree that the incidence and prevalence of dementia increase exponentially with age, although results vary considerably between studies, mainly due to differences in the methodologies and diagnostic criteria used, the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample, and response rates.3

IncidenceAccording to published population studies, the incidence of dementia ranges from 5 to 10 cases per 1000 person-years in patients aged 6468 years, to 4060 cases per 1000 person-years in patients aged 8084 years.3 Few data are available for older age groups due to the lower participation rate and the higher dropout rate among these patients, although some studies report progressive increases in patients aged up to 100 years or above.4

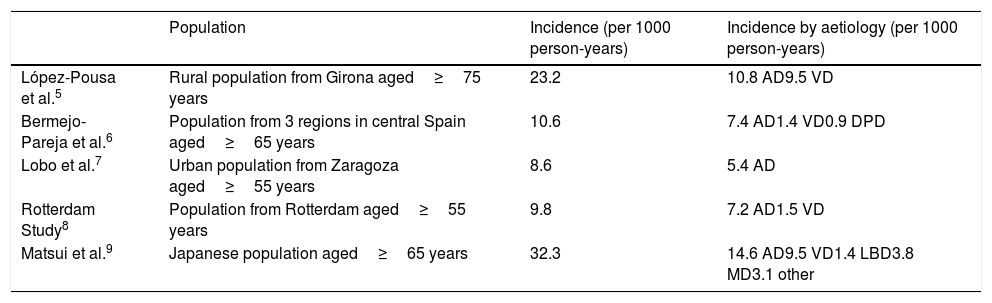

Studies conducted in Spain report similar incidence rates to those of other European countries, with marked age-dependent increases (Table 1).5–9 In all studies, Alzheimer disease is the most frequent cause of dementia. The incidence of dementia appears to be similar in men and women aged 6590 years. Some studies report that after the age of 90, the incidence of dementia, and particularly Alzheimer disease, increases in women.8

Incidence of dementia according to different epidemiological studies, including the main epidemiological studies conducted in Spain.

| Population | Incidence (per 1000 person-years) | Incidence by aetiology (per 1000 person-years) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| López-Pousa et al.5 | Rural population from Girona aged≥75 years | 23.2 | 10.8 AD9.5 VD |

| Bermejo-Pareja et al.6 | Population from 3 regions in central Spain aged≥65 years | 10.6 | 7.4 AD1.4 VD0.9 DPD |

| Lobo et al.7 | Urban population from Zaragoza aged≥55 years | 8.6 | 5.4 AD |

| Rotterdam Study8 | Population from Rotterdam aged≥55 years | 9.8 | 7.2 AD1.5 VD |

| Matsui et al.9 | Japanese population aged≥65 years | 32.3 | 14.6 AD9.5 VD1.4 LBD3.8 MD3.1 other |

AD: Alzheimer disease; DPD: dementia associated with Parkinson's disease; LBD: Lewy body dementia; MD: mixed dementia; VD: vascular dementia.

Several recent epidemiological studies on the incidence of dementia over time report a downward trend in age-specific incidence rates of dementia in countries including Sweden,10 the Netherlands,11 the United Kingdom,12 and the United States.13 Although these decreases are small and are not consistently seen in all studies,14 they are encouraging since they may reflect improvements in health, diet, education, and control of vascular risk factors over the last 3040 years in the countries analysed. Despite these decreases in incidence rates, the total number of cases of dementia is likely to increase in most countries due to increased life expectancy.15

PrevalencePrevalence studies are more numerous than incidence studies and reveal a similar trend, with age-dependent increases in prevalence rates. In general terms, the prevalence of dementia is below 2% in patients aged 6569 years, and doubles every 5 years, reaching 10%17% in the 8084 age group and 30% in patients aged over 90.16 Prevalence is higher in women, perhaps due to their longer life expectancy.

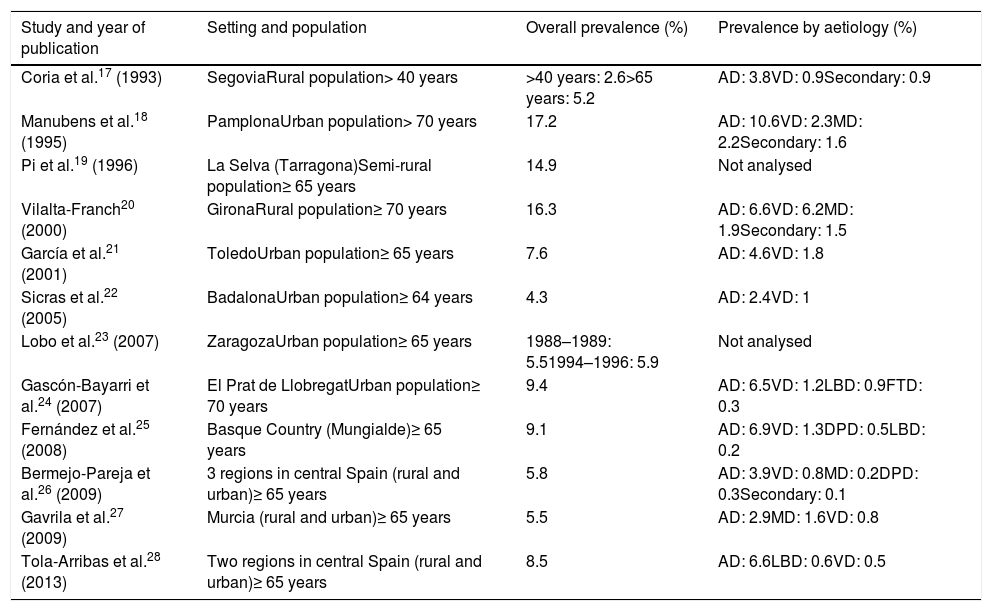

Studies on the prevalence of dementia in Spain17–28 (Table 2) report global prevalence rates ranging from 4.3%22 to 17.2%.18 The highest rates are usually reported by studies including patients older than 70 years18,20,24; prevalence rates range from 4% to 9% in most studies including patients older than 65.19,22,23,25–28 Age is the factor with the greatest impact on dementia prevalence: rates range from 1.5%2% for the 6569 age group to 31%54% for patients older than 90 years.17,18,20 Prevalence of dementia is higher in women for nearly every age group. In our setting, only one study has analysed the progression of dementia prevalence rates, and reports similar overall prevalence rates over a period of 7 years (19881989/19941996), with slightly lower rates in men.23

Main studies on the prevalence of dementia in Spain.

| Study and year of publication | Setting and population | Overall prevalence (%) | Prevalence by aetiology (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coria et al.17 (1993) | SegoviaRural population> 40 years | >40 years: 2.6>65 years: 5.2 | AD: 3.8VD: 0.9Secondary: 0.9 |

| Manubens et al.18 (1995) | PamplonaUrban population> 70 years | 17.2 | AD: 10.6VD: 2.3MD: 2.2Secondary: 1.6 |

| Pi et al.19 (1996) | La Selva (Tarragona)Semi-rural population≥ 65 years | 14.9 | Not analysed |

| Vilalta-Franch20 (2000) | GironaRural population≥ 70 years | 16.3 | AD: 6.6VD: 6.2MD: 1.9Secondary: 1.5 |

| García et al.21 (2001) | ToledoUrban population≥ 65 years | 7.6 | AD: 4.6VD: 1.8 |

| Sicras et al.22 (2005) | BadalonaUrban population≥ 64 years | 4.3 | AD: 2.4VD: 1 |

| Lobo et al.23 (2007) | ZaragozaUrban population≥ 65 years | 1988–1989: 5.51994–1996: 5.9 | Not analysed |

| Gascón-Bayarri et al.24 (2007) | El Prat de LlobregatUrban population≥ 70 years | 9.4 | AD: 6.5VD: 1.2LBD: 0.9FTD: 0.3 |

| Fernández et al.25 (2008) | Basque Country (Mungialde)≥ 65 years | 9.1 | AD: 6.9VD: 1.3DPD: 0.5LBD: 0.2 |

| Bermejo-Pareja et al.26 (2009) | 3 regions in central Spain (rural and urban)≥ 65 years | 5.8 | AD: 3.9VD: 0.8MD: 0.2DPD: 0.3Secondary: 0.1 |

| Gavrila et al.27 (2009) | Murcia (rural and urban)≥ 65 years | 5.5 | AD: 2.9MD: 1.6VD: 0.8 |

| Tola-Arribas et al.28 (2013) | Two regions in central Spain (rural and urban)≥ 65 years | 8.5 | AD: 6.6LBD: 0.6VD: 0.5 |

AD: Alzheimer disease; DPD: dementia associated with Parkinson's disease; FTD: frontotemporal dementia; LBD: Lewy body dementia; MD: mixed dementia; VD: vascular dementia.

Alzheimer disease is the most frequent cause of dementia (accounting for 60%80% of cases), followed by vascular dementia, whether mixed (vascular dementia and Alzheimer disease) or pure (20%30%). The clinical and epidemiological differences between pure and mixed vascular dementia are not clearly established; both types of dementia frequently appear in the same group, making it difficult to compare studies. A third group comprises such other neurodegenerative diseases as Lewy body dementia, dementia associated with Parkinson's disease, and frontotemporal dementia. Secondary dementia has a low prevalence, ranging from 0.1% to 1.6%.17,20,26

Early-onset dementia (beginning before the age of 65) has a different aetiological distribution. A study conducted in the Spanish province of Girona29 revealed that the most frequent cause of early-onset dementia is Alzheimer disease (42.4%), followed by secondary dementias (18.1%), vascular dementia (13.8%), and frontotemporal dementia (9.7%); the latter has been found to be the second most frequent cause of early-onset dementia, after Alzheimer disease, in studies conducted in other countries.30

ProjectionsDue to progressive population ageing, dementia prevalence is expected to increase worldwide. In Spain, one in 3 people will be older than 65 years by 2050. According to data from the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE), 431000 people had dementia in 2004. If estimates are correct, dementia will affect nearly 600000 people in 2030 and around one million by 2050.31 However, these figures may underestimate the extent of the problem, as a considerable percentage of patients are not diagnosed or are not reflected in official statistics. For example, a 2009 study analysing 9 major prevalence studies conducted in Spain between 1990 and 2008 estimated that dementia affected 600000 people, 400000 of whom would have Alzheimer disease; results should be interpreted with caution due to the limited number of studies conducted in southern Spain.32

The latest Alzheimer's Disease International report, published in 2016, estimates that dementia affects around 46 million people worldwide. If population ageing and dementia incidence rates remain stable, 131 million people are expected to have dementia by 2050,33 of whom two-thirds will live in developing countries. The WHO has warned of the potential consequences of this and calls on policymakers to take measures aimed at reducing the social and healthcare impact of this devastating disease,3 allocating more resources, and developing national strategies to fight Alzheimer disease.

Morbidity and mortalityComorbidities of dementiaPatients with dementia frequently have more comorbidities than people without dementia. According to a study conducted in Spanish primary care centres, patients with dementia had a mean of 3.7 comorbidities, compared to 2.4 in people older than 65 years without dementia.34 Patients with dementia frequently present vascular risk factors (arterial hypertension in 20.7% and diabetes mellitus in 7.1%) and associated problems (cerebrovascular diseases, heart disease, other conditions).35

These patients often present conditions directly attributable to cognitive and functional impairment,36 such as increased risk of falls (17.7% of patients have fractures at some point) or infections (14% have had pneumonia) or the consequences of the progressive loss of mobility.

Depressive symptoms constitute the most frequent psychological manifestation in patients with mild to moderate dementia, and range from adaptive reactions to episodes of major depression.37 Although prevalence rates vary considerably according to symptom severity and the stage of dementia, depressive symptoms have been observed in over half of patients, with major depression in 20%25% of patients with any type of dementia.

Comorbidities are strongly linked to adverse drug reactions; patients with dementia receive an average of over 5 drugs.35,38 Patients with Alzheimer disease present increased likelihood of hospital admission (up to 3.6 times higher), usually secondary to infections occurring during the advanced stages of the disease.39 Given the greater complexity of managing these patients (difficulties in clinical data gathering, poor tolerance to diagnostic procedures, risk of iatrogenesis due to polytherapy), hospital stays are longer, more complex, more costly, and associated with higher mortality rates.40 Presence of cognitive impairment during hospitalisation is a reliable predictor of functional impairment after admission.41

According to the INE,42 the total number of hospital admissions due to dementia in our setting is not significant (8/100000 population in 2015 vs 10228/100000 for all causes). We should bear in mind that these figures only reflect the main diagnosis motivating hospital admission and do not take into account the numerous hospital admissions secondary to complications of dementia. In 2015, the mean hospital stay for patients with senile, presenile, and vascular dementia (according to the now obsolete terminology of the ICD-9-CM) was 57.41 days, compared to 6.66 days for all discharges; these figures are striking and have significant implications for healthcare management.

Mortality due to dementiaDementia is one of the main predictors of death, along with other better known predictors including cancer and cardiovascular disease.43 Alzheimer disease accounts for 4.9% of deaths in patients older than 65 years; the risk increases considerably with age, reaching 30% in men older than 85 years and 50% in women of the same age.44 According to population studies conducted in our setting, the relative risk of death in patients with dementia compared to controls, considering all age groups, ranges from 1.8 to 3.2 for all types of dementia; median survival time ranges from 3.4 to 4.7 years.45–47 For Alzheimer disease, population studies report a median survival time of 3.15.9 years45–47; survival times are shorter in patients with early onset, poor cognitive and functional status, or systemic comorbidities.48 For vascular dementia, survival times range from 2.5 to 3.9 years.47,49

Various factors have been associated with shorter dementia survival times, with age, male sex, dementia severity, and the number of associated comorbidities being most consistently identified in population studies.46,47 Some hospital series report an association between dementia and frontal dysfunction, extrapyramidal symptoms, gait alterations, and frequent falls.48

According to 2015 mortality data from the INE,50 nervous system diseases are the fourth most common cause of death in Spain (6.1% of all deaths). By disease, dementia ranks fourth, accounting for 20442 deaths (13800 women and 6642 men), whereas Alzheimer disease ranks seventh, with 15578 deaths (11004 women and 4574 men). Together, dementia and Alzheimer disease cause more deaths that ischaemic heart diseases (33769 deaths).50 By sex, 60%70% of patients who die due to dementia are women.

These data show the impact of dementia on mortality but may not reflect the whole picture; several studies have shown that dementia is rarely reported as the underlying cause of death on death certificates. In a study conducted in Spain, diagnosis of dementia only appeared on 20% of all death certificates for this patient group47; similar figures have been reported in other countries.51 The under-reporting of dementia on death certificates may be due to the social (and sometimes medical) perception that dementia in elderly patients is not a disease but rather a consequence of ageing. The fact that dementia is rarely reported as the cause of death results in underestimation in official statistics. This is a problem for public health since healthcare authorities need to allocate more resources to managing the most prevalent diseases.

Disability and dependenceDementia and disabilityDementia decreases patients’ functional capacity, resulting in long periods of disability and dependence; this depends not only on patient survival but also on age, an important independent factor. According to the survey on disability, personal autonomy, and dependency status conducted in Spain in 2008,52 to be updated in 2017, the disability rate is 85.45 cases per 1000 population (women: 101.2/1000 population; men: 69.52/1000 population). According to the survey, dementia is the fifth most frequent diagnosis (with over 330000 patients, not including those with cerebrovascular disease), after joint disorders, depression, cataracts, and ischaemic heart disease.

Dementia is one of the leading causes of institutionalisation in Western countries.53 The annual rate of institutionalisation in Spain is 10.5%.54 Approximately 36% of all institutionalised patients with disability have dementia (14.3% with Alzheimer disease and 21.7% with other types of dementia).52

Dementia and dependenceDementia is the chronic disease that most frequently causes dependence, ranking ahead of stroke, Parkinson's disease, and cardiovascular diseases.55 Given that diagnosis requires a loss of functional capacity, patients soon begin to depend on other people, usually close relatives (in 85% of cases). Dementia is therefore a “social and public health disease,” as it affects not only patients and their caregivers or families, but also public and private healthcare and social institutions.56

According to the white paper on dependence57 published by the Spanish Institute for Social Services and the Elderly, 246412 people older than 65 years are expected to be highly dependent by 2020, compared to 163334 patients in 2005. In most of these patients, dependence will be linked to dementia (88.47% of all dependent patients). Disability and the resulting dependence constitute an essential factor in developing comprehensive care strategies for dementia in the context of the Spanish legislation governing the care of dependent people.58

Economic impact of dementiaEconomic cost of dementiaThe economic costs of dementia care can be divided into 2 categories:

Direct costs: quantifiable costs directly related to patient management. These include healthcare direct costs (drugs and other healthcare resources) and non-healthcare direct costs associated with homecare, institutionalisation, home adaptations, transport, etc. Some studies59 account for the costs of informal care as non-healthcare direct costs, assigning caregivers the costs of a homecare worker.

Indirect costs: costs associated with unpaid work, such as time dedicated to patient care by family members, loss of the patient's and the caregiver's productivity at work, or healthcare-related costs associated with caregiver burden. Some studies refer to these costs as “non-healthcare costs”; they are not easily quantified.60

Variables affecting the cost of dementiaCosts vary with disease progression. In early stages, indirect costs are higher than direct costs: around 70% of the total cost is associated with informal care. In advanced stages of the disease, costs are mostly direct, associated with institutionalisation.61

The factors with the greatest impact on the cost of dementia are disease severity, level of dependence in the activities of daily living,62 and presence of comorbidities, neuropsychiatric disorders, and extrapyramidal symptoms.61 Other variables are such sociodemographic factors60 as the caregiver's level of education, the type of relationship between patient and caregiver, and geographic setting (rural or urban).

Poorer cognitive function and decreased ability to perform activities of daily living are also strong markers of increased healthcare cost.60 We should also highlight the impact of behavioural disorders not only on direct costs but also on indirect costs and on global caregiver burden. Caregivers of patients with behavioural disorders need to devote up to an additional 3.5hours per day to caring for their patients; this is equivalent to one-third more than the time required by patients with no behavioural disorders.63

Cost of Alzheimer-type dementia in Spain: direct and indirect costsAccording to estimates for 2010, the cost of dementia in Spain amounted to more than €16billion64; this figure represents approximately 15% of total healthcare expenditure (public and private healthcare), amounting to €99.899 billion.65 This makes dementia the most costly neurological disease overall, and the second greatest in terms of healthcare costs per patient per year, after multiple sclerosis (€29389 vs €31226).66 Also in 2010, direct costs represented half of the total cost of dementia in Western European countries.

Around 80% of patients with Alzheimer disease are cared for by their families, who bear 88% of total costs.60 The remaining 12% is covered by public funds and corresponds to part of the direct costs (mainly healthcare direct costs).60 In the case of dementia, non-healthcare costs constitute the greatest part of total costs, mainly due to informal care.

Direct costs. Calculating direct costs is less straightforward; intervals are not clearly established and depend on the method for estimating costs, with wide ranges for healthcare and non-healthcare direct costs. Healthcare direct costs increase as the disease progresses. In fact, healthcare costs of patients with Alzheimer disease are 34% higher than those of a similar population without the disease, as the disease is associated with more visits to the emergency department, more hospital admissions, longer hospital stays, and a greater need for homecare.67 Costs associated with pharmacological treatment for dementia are moderate and account for 8% of the total cost.60

Non-healthcare direct costs per patient per year in our setting range from 1498 to 5589 international dollars (int$). In advanced stages of the disease, institutionalisation, day centres, and professional caregivers account for the bulk of the direct costs.

Indirect costs. In patients with advanced dementia, the increased indirect costs can triple the total costs associated with the management of mild dementia, with annual costs ranging from int$26425 to int$69545.68 Indirect costs associated with informal care amount to a mean of 52% of total costs. According to some analyses, the expenses associated with informal care decrease with disease severity while expenses derived from formal, paid care work increase.68 However, other statistical analyses show progressive increases in expenses arising from informal care. This occurs when patients’ condition worsens but they cannot be institutionalised or cared for by professional caregivers. This being the case, indirect costs may represent up to 73% of total costs in patients with advanced dementia.69 This equates to 80105hours per week of care provided to the patient with dementia.70

Interestingly, costs vary according to certain sociodemographic characteristics: healthcare expenses are lower in rural settings71 and higher when the informal caregiver is the patient's partner or has university studies.

Impact on the familyA patient with Alzheimer disease requires approximately 70hours of care per week, including basic needs, medication management, healthcare, and management of symptoms and potential conflicts.72 In most cases (80%), informal caregivers are relatives of the patient.60 The greatest burden usually falls on a single person, who is referred to as the primary caregiver. Patients’ functional capacity decreases as the disease progresses, increasing the burden on the caregiver and leading to caregiver overload. Caring for patients with dementia generates higher levels of stress and anxiety than caring for patients with other chronic disabling diseases; over 75% of caregivers of patients with dementia have stress or anxiety.73 As a result of overload, caregivers of patients with dementia are considerably more likely to develop psychological and physical disorders than age-matched controls. Furthermore, they present higher levels of depression, somatic symptoms, and social isolation, and poorer self-perceived health, and require psychological therapy and psychotropic drugs more frequently than do the general population. They also have less time for their own everyday activities.74,75 These problems are not resolved with patient institutionalisation or death, but rather may last for several years, with rates of pathological grief in excess of 20% among this population.76

Caregiver overload depends on a number of factors:

Patient-related factors. According to most studies, behaviour disorders play a major role in the development of caregiver overload and family stress. Other less significant factors are functional alterations and cognitive impairment.77

Caregiver-related factors. These include a lack of social support, dedication exclusively to patient care, lack of coping skills and strategies, health, and female sex.78

Caregiver overload results in a significant decrease in caregiver quality of life. Caregiver quality of life is invariably linked to patient quality of life78; poor caregiver quality of life is the main predictor of institutionalisation of patients with dementia.54 Other factors involved in patient institutionalisation include caregiver age over 60 years, caregiver burden, or the caregiver not being the patient's spouse, son, or daughter.79 Improving depressive symptoms in caregivers (present in up to 50% of spouses) delays institutionalisation80; this underscores the need for multidimensional action plans.

Situation of dementia care in SpainDiagnosis of cognitive impairmentA considerable percentage of people with cognitive impairment or dementia may not have been formally diagnosed. However, few studies have been conducted on the topic in our setting. In a population study conducted in the town of Leganés, near Madrid, 70% of patients with dementia had not been diagnosed by healthcare services.81 The percentage of patients with undiagnosed dementia is closely linked to dementia severity: severe cases are more frequently diagnosed than mild cases (64% vs 5%). Although these figures may seem alarming or exaggerated, they do not significantly differ from those reported by studies conducted in other countries. Studies in other European countries report rates of undiagnosed dementia of up to 58%82; rates in the United States are even higher (65%).83 A population study recently conducted in Spain (DEMINVALL) reported an overall prevalence rate of 8.5%; 55% of these patients had not previously been diagnosed with dementia. This reflects a slight improvement in undiagnosed dementia, although rates are still concerning.28 The high rate of patients with underdiagnosed dementia may be explained at different levels:

- -

At the patient and family level: dementia is often not perceived as a disease by patients and their relatives, who regard some symptoms as normal or typical of ageing, and early symptoms are usually mild and heterogeneous, leading to diagnostic delays.

- -

At the primary care level: primary care physicians may be poorly trained on dementia, with a tendency not to use brief cognitive tests as they feel they are time-consuming; they rely too heavily on the Mini-Mental State Examination (which has low sensitivity for mild dementia), and rarely enquire about memory loss symptoms until more severe symptoms appear or the patient develops behaviour disorders.83

- -

At the specialist level: specialists often feel that there is a lack of treatment options, or that consultations are too short.83

There is controversy around the need for early diagnosis of cognitive impairment due to the current lack of curative or disease-modifying treatments for dementia. However, early diagnosis has some benefits: the possibility of starting non-pharmacological treatment, scheduling the most appropriate psychosocial intervention, reducing traffic accidents (driving assessment of patients with dementia),84 facilitating healthcare decision making for patients’ families, or reducing healthcare costs associated with homecare and specialised care. Efforts should be made to better inform the general population about dementia and to raise awareness among healthcare professionals of the importance of early diagnosis in order to improve dementia training among primary care physicians and to increase the number of units specialising in the diagnosis and treatment of cognitive impairment.

Dementia careCaring for patients with dementia is a complex, multidisciplinary task requiring the involvement of families, physicians, and social services.

Cognitive symptoms have become one of the main reasons for consultation at neurology departments. Around 18.5% of patients visiting neurology departments complain about memory problems and suspected cognitive impairment.85 Among patients older than 65 years, these constitute the main reason for neurology consultations (35%).86 This represents a conflict with the short consultation times in primary care (510minutes) and specialised care (1020minutes), which are insufficient to evaluate cognitive function. Primary and specialised care consultation times should be increased and units specialising in dementia should be created for proper assessment of these patients and to enable easier access to biomarkers of dementia in cases of uncertain diagnosis. In addition to improving diagnosis of cognitive impairment, prevention programmes should be developed to promote physical exercise and control vascular risk factors, which may have a great impact on the prevalence of dementia in the near future.87

The role of social services is essential in the management of patients with dementia. In Spain, the Law for Dependent People specifies the resources to be used in the care of patients with dementia58; these include strategies for preventing dependence and promoting personal autonomy, telephone-based support, home care, day/night-care centres, and nursing homes. Patients also benefit from economic support aimed at covering the costs of day centres or nursing homes or the cost of a personal assistant for dependent people. Since 2006, provision of this kind of economic support requires that the patient be recognised officially as a dependent person; on occasion, this requirement constitutes a bottleneck for economic support.

In January 2017, the Spanish Institute for Social Services and the Elderly had received 1625864 requests for dependence assessments, 1518289 of which (93.38%) had been resolved: 26.16% of patients (n=397123) were assigned level I dependence, 29.98% (n=455219) had level II dependence, and 23.92% (n=363228) had level III dependence, which corresponds to the most severe cases. A total of 1215570 patients (80.06% of requests) were eligible for economic support. However, only 71.8% of this group (873706 patients) actually received financial support.88

ConclusionsPopulation ageing is a major healthcare concern as it leads to an increase in the prevalence of such neurodegenerative diseases as Alzheimer disease and other types of dementia. Comprehensive programmes should be developed and more resources should be allocated for research, prevention, early diagnosis, multidimensional treatment, and multidisciplinary management of dementia, involving both patients and primary caregivers, in order to reduce the healthcare, social, and economic burden of dementia. In line with WHO recommendations,2 Spain should develop a national plan for Alzheimer disease similar to those implemented in other countries in our setting. The Spanish National Dementia Group has set the objective of drafting a plan for Alzheimer disease for approval in the 2017 parliamentary term.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Villarejo Galende A, Eimil Ortiz M, Llamas Velasco S, Llanero Luque M, López de Silanes de Miguel C, Prieto Jurczynska C. Informe de la Fundación del Cerebro. Impacto social de la enfermedad de Alzheimer y otras demencias. Neurología. 2021;36:39–49.