To identify possible predictors of seizure cluster or status epilepticus (SE) and to evaluate whether these patients receive greater interventions in emergency departments.

MethodologyWe conducted a secondary analysis of the ACESUR Registry, a multipurpose, observational, prospective, multicentre registry of adult patients with seizures from 18 emergency departments. Clinical and care-related variables were collected. We identified risk factors and risk models for seizure cluster or SE and assessed the effect of interventions by prehospital emergency services and the hospital emergency department.

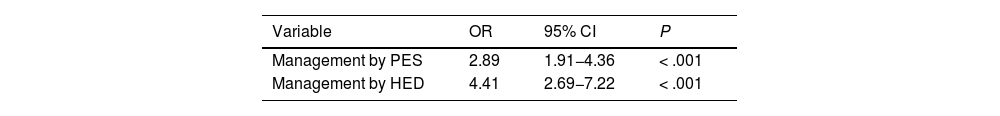

ResultsWe identified a total of 186 (28%) patients from the ACESUR registry with seizure cluster (126 [19%]) or SE (60 [9%]); the remaining 478 patients (72%) had isolated seizures. The risk model for seizure cluster or SE in the emergency department included Charlson Comorbidity Index scores ≥ 3 (OR: 1.60; 95% CI, 1.05–2.46; P=.030), ≥ 2 habitual antiepileptic drugs (OR: 2.29; 95% CI, 1.49–3.51; P<.001), and focal seizures (OR: 1.56; 95% CI, 1.05–2.32; P=.027). The area under the curve of the model was 0.735 (95% CI, 0.693–0.777; P=.021). Patients with seizure cluster and SE received more aggressive interventions both by prehospital emergency services (OR: 2.89; 95% CI, 1.91–4.36; P<.001) and at the emergency department (OR: 4.41; 95% CI, 2.69–7.22; P<.001).

ConclusionsThis risk model may be of prognostic value in identifying adult patients at risk of presenting seizure cluster or SE in the emergency department. In our sample, these patients received more aggressive treatment than adult patients with isolated seizures before arriving at hospital, and even more so in the emergency department.

Identificar posibles factores predictores de crisis epilépticas en acúmulos o Estado Epiléptico (EE) y evaluar si estos pacientes reciben una mayor intervención en urgencias.

MetodologíaAnálisis secundario del Registro ACESUR el cual es un registro observacional de cohortes multipropósito, prospectivo y multicéntrico de pacientes adultos con crisis epilépticas en 18 servicios de urgencias. Se recogen variables clínico-asistenciales. Se identifican factores y modelo de riesgo de presentar crisis en acúmulos o EE y se avalúa el efecto de intervención en servicios de urgencias extrahospitalarios (SUEH) y hospitalarios (SUH).

ResultadosDel registro ACESUR se analizan 186 (28%) con crisis en acúmulos (126 (19%)) o EE (60 (9%)) frente a 478 (72%) pacientes con crisis aislada. El modelo de riesgo de crisis en acúmulo o EE en urgencias incluyó la presencia de alta comorbilidad según índice de Charlson ≥ 3 (OR: 1,60; IC95%: 1,05-2,46; p=0,030), ≥ 2 fármacos antiepilépticos habituales (OR: 2,29; IC95%: 1,49-3,51; p<0,001) y crisis focal (OR: 1,56; IC95%: 1,05-2,32; p=0,027). El ABC del modelo fue de 0,735 (IC95%: 0.693-0.777; p=0,021). La intervención en pacientes con crisis en acúmulos y EE fue mayor en los SUEH (OR: 2,89; IC95%: 1,91-4,36; p<0,001) y en los SUH (OR: 4,41; IC95%: 2,69-7,22; p<0,001).

ConclusionesEl modelo presentado podría ser una herramienta con valor predictivo de utilidad para identificar al paciente adulto con riesgo de presentar crisis en acúmulos o estado epiléptico en urgencias. Estos pacientes recibieron una mayor intervención frente a pacientes con crisis epiléptica aislada por parte de los SUEH y más aún por los SUH en nuestra muestra.

Epileptic seizures are a frequent neurological disorder, accounting for 0.3%–1% of all patients attended at emergency departments.1–4

Status epilepticus (SE) is a neurological emergency representing up to 10% of all epileptic seizures,1,5 and is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality.1,6 The seizure duration considered in definitions of SE has shortened in recent decades, to 5minutes for convulsive SE and 10minutes for focal SE with impaired awareness, as established by Trinka et al.7 These authors also establish a second time point after which there is an increased risk of neurological repercussions (30minutes for convulsive SE and 60minutes for focal SE with impaired awareness).

Seizure clusters constitute another form of presentation of epileptic seizures, and account for up to 20% of all seizures.8 Despite a lack of consensus, the most widely accepted definition of a seizure cluster is the occurrence of at least 2 seizures within 24hours. Some authors consider seizure clusters to increase the risk of SE, and have included this type of seizure in such instruments as the ADAN scale.9 Seizure clusters may therefore be considered a predictor of SE.

A consensus document on the emergency treatment of patients with seizures was recently published by the Spanish Society of Epilepsy, the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Epilepsy Study Group, and the Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine’s Neurostroke Study Group.10 This document introduces the novel concept of urgent seizure, which encompasses such prolonged seizures as SE, seizure clusters, and seizures considered high-risk due to the presence of certain risk factors.

In the ACESUR registry (Acute Epileptic Seizures in the Emergency Department), SE and seizure clusters accounted for 9% and 19%, respectively, of all epileptic seizures.5 These types of seizures are associated with poorer prognosis,6–8 although it is unclear whether there are differences in the characteristics of these patients or the care they receive at the emergency department.

Our study aims to identify predictors of seizure clusters or SE and to evaluate whether patients with these seizures are more frequently attended by prehospital emergency services (PES) and hospital emergency departments (HED).

MethodsACESUR is a multipurpose, observational, prospective, multicentre cohort registry including patients from 18 HEDs selected by systematic sampling in 2017.5 The study was approved by our hospital’s clinical research ethics committee. The registry includes all patients aged at least 18 years and diagnosed with epileptic seizures at the HED. Written informed consent was given by the patients or their legal representatives.

We created an electronic database with the information provided by patients or their families and the data included in the electronic clinical records (clinical and management variables of the index visit to the HED).

We gathered data on the following clinical characteristics: form of presentation (seizure cluster for ≥ 2 seizures over the last 24h; SE for convulsive seizures lasting more than 5minutes or non-convulsive seizures lasting more than 10minutes7; or isolated seizures [ie, not presenting in clusters or as SE]), age (mean and whether the patient was younger than or older than 65 years), sex, comorbidity burden according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), history of epilepsy, baseline functional independence according to the Barthel Index (BI),5 number of pharmacological treatments and number of antiepileptic drugs (AED) habitually used, seizure semiology (focal vs generalised), aetiological classification of seizures (acute or provoked symptomatic seizures, unprovoked or remote symptomatic seizures, idiopathic seizures), and visits to the HED in the previous semester.

We also gathered the following data about the care provided by PES: attended by PES (yes/no; at home/other), transported by ambulance (yes/no), and pharmacological treatment (benzodiazepines, other AEDs). The variable “management by PES” (yes/no) was defined as the intervention of PES or transportation by ambulance plus administration of pharmacological treatment.

Regarding the care provided at the HED, we gathered the following information: triage category (immediate-emergency [I–II], semi-urgent [III–IV]), specific complementary tests (head CT, brain MRI, EEG, lumbar puncture), consultation with on-call neurology service, emergency pharmacological treatment (benzodiazepines, other AEDs), prolonged stay at the HED (observation, >24h), destination at discharge (home, other hospital department [neurology, intensive care, other], or death at the HED).

The variable “management by HED” (yes/no) was defined as a triage category I–II, performance of a specific complementary test (CT, MRI, EEG, lumbar puncture), emergency pharmacological treatment (benzodiazepines, other AEDs), consultation with the on-call neurology department, or prolonged stay at the HED or hospitalisation.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables are expressed as frequencies, whereas quantitative variables are expressed as means and standard deviation (SD), or median and quartiles 1 and 3 for non-normally distributed data.

We performed a univariate analysis of the variables potentially associated with seizure clusters or SE. Means were compared using the t test. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used for non–normally distributed quantitative variables. We evaluated the association between qualitative variables with the chi-square test, or the Fisher exact test when more than 25% of the expected values were below 5.

To analyse predictors of seizure clusters or SE, we used mixed effects logistic regression models to control for the impact of the hospital in which the patient was attended. The main outcome variable was diagnosis of seizure cluster or SE at the HED. The healthcare centre was considered the random variable and variables linked to the predictors of interest were treated as fixed variables; thus, the model included all the factors found to be associated with the adverse event (with P-values<.10 and/or considered clinically relevant) in the univariate analysis. The final set of variables for the model was determined with backward stepwise selection (P<.10).

The discriminative power of the predictive model was analysed by calculating the ROC curve and its 95% confidence interval. We evaluated the calibration of the model with the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test.

Lastly, the effect of the variables “intervention by the PES” and “intervention at the emergency department” was also analysed. We calculated odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Type I errors or alpha errors below 0.05 resulted in rejection of the null hypothesis. Data were analysed using the STATA statistical software, version 12.0.

ResultsThe ACESUR registry included 664 patients from the following healthcare centres: 86 (13%) from H. U. Clínico San Carlos (Madrid), 51 (7.7%) from H. U. Clínico de Valladolid (Valladolid), 126 (19%) from C. H. U. Granada (Granada), 13 (2%) from H. Virgen de la Luz (Cuenca), 33 (5%) from H. U. Puerta de Hierro (Madrid), 11 (1.7%) from H. U. de Guadalajara (Guadalajara), 10 (1.5%) from H. Son Llatzer (Palma de Mallorca), 26 (3.9%) from H. U. de Canarias (Tenerife), 22 (3.3%) from H. U. Cabueñes (Gijón), 32 (4.8%) from H. U. Clínico de Salamanca (Salamanca), 12 (1.8%) from H. U. La Princesa (Madrid), 21 (3.2%) from H. U. Getafe (Madrid), 4 (0.6%) from H. G. U. Reina Sofía (Murcia), 71 (10.7%) from H. U. 12 de Octubre (Madrid), 41 (6.2%) from H. U. La Paz (Madrid), 86 (13%) from H. U. Miguel Servet (Zaragoza), 11 (1.7%) from H. G. de Villarrobledo (Albacete), and 8 (1.2%) from H. U. Príncipe de Asturias (Alcalá de Henares).5

A total of 126 cases (19%) were classified as seizure clusters, 60 (9%) as SE (convulsive in 41 and non-convulsive in 19), and 478 (72%) as isolated seizures. We analysed 186 patients (28%) with seizure clusters or SE and 478 patients (72%) with isolated seizures.

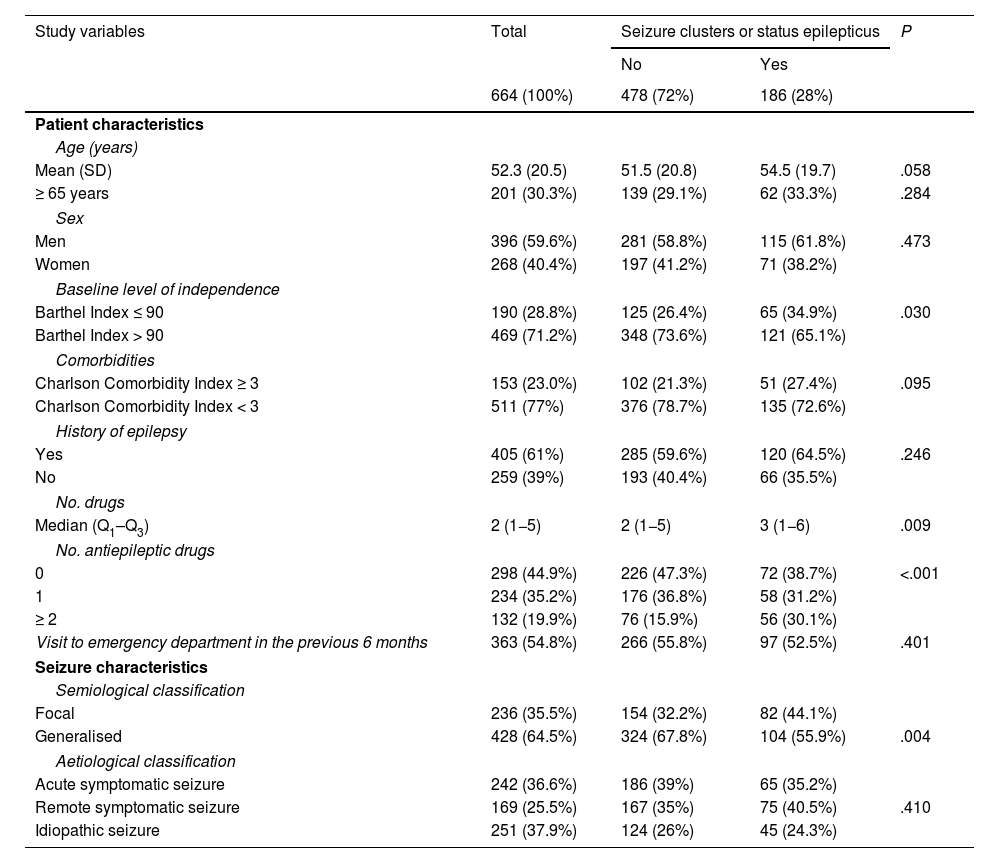

Table 1 compares the characteristics of the patients with seizure clusters or SE against those of patients with isolated seizures. Older age, higher level of dependence (BI≤90), greater comorbidity burden (CCI≥3), higher numbers of drugs and AEDs, and focal seizures were associated with a greater risk of presenting seizure clusters or SE. History of epilepsy was more frequent among patients with seizure clusters or SE, although differences were not significant. A higher percentage of patients with isolated seizures had visited the emergency department in the previous 6 months. Acute symptomatic seizures were more frequent among patients with isolated seizures, whereas remote symptomatic seizures were more frequent among patients with seizure clusters or SE.

Univariate analysis of the clinical characteristics of patients attended by emergency services with seizure clusters or status epilepticus vs patients with isolated seizures.

| Study variables | Total | Seizure clusters or status epilepticus | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| 664 (100%) | 478 (72%) | 186 (28%) | ||

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 52.3 (20.5) | 51.5 (20.8) | 54.5 (19.7) | .058 |

| ≥ 65 years | 201 (30.3%) | 139 (29.1%) | 62 (33.3%) | .284 |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 396 (59.6%) | 281 (58.8%) | 115 (61.8%) | .473 |

| Women | 268 (40.4%) | 197 (41.2%) | 71 (38.2%) | |

| Baseline level of independence | ||||

| Barthel Index ≤ 90 | 190 (28.8%) | 125 (26.4%) | 65 (34.9%) | .030 |

| Barthel Index > 90 | 469 (71.2%) | 348 (73.6%) | 121 (65.1%) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥ 3 | 153 (23.0%) | 102 (21.3%) | 51 (27.4%) | .095 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index < 3 | 511 (77%) | 376 (78.7%) | 135 (72.6%) | |

| History of epilepsy | ||||

| Yes | 405 (61%) | 285 (59.6%) | 120 (64.5%) | .246 |

| No | 259 (39%) | 193 (40.4%) | 66 (35.5%) | |

| No. drugs | ||||

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 2 (1−5) | 2 (1−5) | 3 (1−6) | .009 |

| No. antiepileptic drugs | ||||

| 0 | 298 (44.9%) | 226 (47.3%) | 72 (38.7%) | <.001 |

| 1 | 234 (35.2%) | 176 (36.8%) | 58 (31.2%) | |

| ≥ 2 | 132 (19.9%) | 76 (15.9%) | 56 (30.1%) | |

| Visit to emergency department in the previous 6 months | 363 (54.8%) | 266 (55.8%) | 97 (52.5%) | .401 |

| Seizure characteristics | ||||

| Semiological classification | ||||

| Focal | 236 (35.5%) | 154 (32.2%) | 82 (44.1%) | |

| Generalised | 428 (64.5%) | 324 (67.8%) | 104 (55.9%) | .004 |

| Aetiological classification | ||||

| Acute symptomatic seizure | 242 (36.6%) | 186 (39%) | 65 (35.2%) | |

| Remote symptomatic seizure | 169 (25.5%) | 167 (35%) | 75 (40.5%) | .410 |

| Idiopathic seizure | 251 (37.9%) | 124 (26%) | 45 (24.3%) | |

SD: standard deviation.

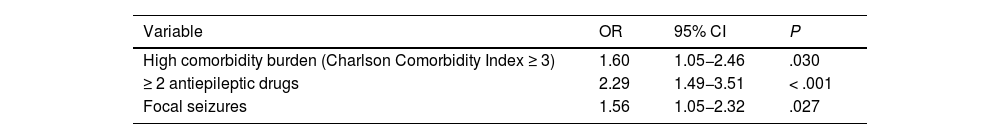

The risk model initially included the following potential predictors of seizure clusters or SE at the emergency department: age, high level of dependence (BI<90), high comorbidity burden (CCI≥3), treatment with ≥ 2 drugs, treatment with ≥ 2 AEDs, and focal seizures. The variables remaining in the last step were high comorbidity burden (OR: 1.6; 95% CI, 1.05–2.46; P=.030), treatment with ≥ 2 AEDs (OR: 2.29; 95% CI, 1.49–3.51; P<.001), and focal seizures (OR: 1.56; 95% CI, 1.05–2.32; P=.027) (Table 2). The area under the ROC curve was 0.735 (95% CI, 0.693−0.777; P=.021). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test yielded a P-value of .936.

Independent predictors of seizure clusters or status epilepticus identified in the multivariate analysis.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| High comorbidity burden (Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥ 3) | 1.60 | 1.05−2.46 | .030 |

| ≥ 2 antiepileptic drugs | 2.29 | 1.49−3.51 | < .001 |

| Focal seizures | 1.56 | 1.05−2.32 | .027 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

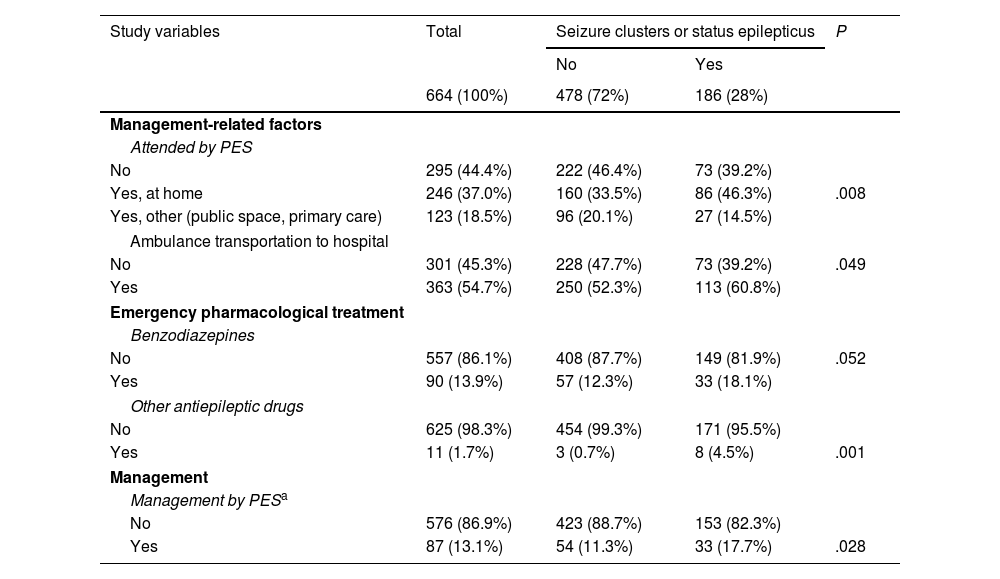

The results of the univariate analysis of the care provided by PES to patients with seizure clusters or SE vs those with isolated seizures are summarised in Table 3. Patients with seizure clusters or SE were more frequently attended by PES, especially at their homes, and were more frequently transported to hospital by ambulance. Furthermore, these patients were more likely to receive first- and second-line pharmacological treatment.

Univariate analysis of the care provided by prehospital emergency services to patients with seizure clusters or status epilepticus vs patients with isolated seizures.

| Study variables | Total | Seizure clusters or status epilepticus | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| 664 (100%) | 478 (72%) | 186 (28%) | ||

| Management-related factors | ||||

| Attended by PES | ||||

| No | 295 (44.4%) | 222 (46.4%) | 73 (39.2%) | |

| Yes, at home | 246 (37.0%) | 160 (33.5%) | 86 (46.3%) | .008 |

| Yes, other (public space, primary care) | 123 (18.5%) | 96 (20.1%) | 27 (14.5%) | |

| Ambulance transportation to hospital | ||||

| No | 301 (45.3%) | 228 (47.7%) | 73 (39.2%) | .049 |

| Yes | 363 (54.7%) | 250 (52.3%) | 113 (60.8%) | |

| Emergency pharmacological treatment | ||||

| Benzodiazepines | ||||

| No | 557 (86.1%) | 408 (87.7%) | 149 (81.9%) | .052 |

| Yes | 90 (13.9%) | 57 (12.3%) | 33 (18.1%) | |

| Other antiepileptic drugs | ||||

| No | 625 (98.3%) | 454 (99.3%) | 171 (95.5%) | |

| Yes | 11 (1.7%) | 3 (0.7%) | 8 (4.5%) | .001 |

| Management | ||||

| Management by PESa | ||||

| No | 576 (86.9%) | 423 (88.7%) | 153 (82.3%) | |

| Yes | 87 (13.1%) | 54 (11.3%) | 33 (17.7%) | .028 |

PES: prehospital emergency services.

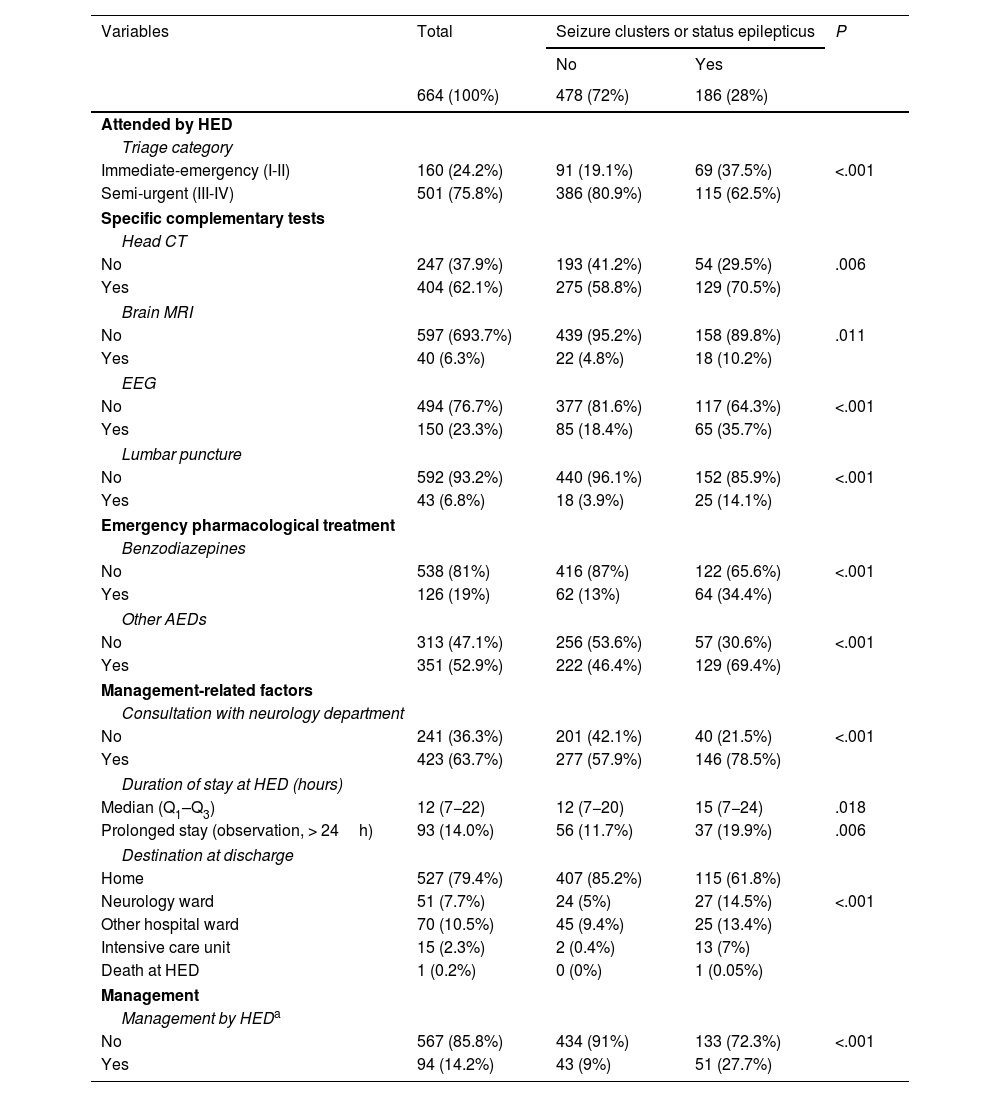

Table 4 presents the results of the univariate analysis on the care provided at HEDs to patients with seizure clusters or SE vs those with isolated seizures. Patients with seizure clusters or SE were assigned a triage category III, underwent specific complementary tests, and received AEDs more frequently than patients with isolated seizures. Furthermore, this group presented more frequent consultations with the neurology department, longer stays at the HED, and higher rates of hospitalisation.

Univariate analysis of the care provided by hospital emergency departments to patients with seizure clusters or status epilepticus vs patients with isolated seizures.

| Variables | Total | Seizure clusters or status epilepticus | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| 664 (100%) | 478 (72%) | 186 (28%) | ||

| Attended by HED | ||||

| Triage category | ||||

| Immediate-emergency (I-II) | 160 (24.2%) | 91 (19.1%) | 69 (37.5%) | <.001 |

| Semi-urgent (III-IV) | 501 (75.8%) | 386 (80.9%) | 115 (62.5%) | |

| Specific complementary tests | ||||

| Head CT | ||||

| No | 247 (37.9%) | 193 (41.2%) | 54 (29.5%) | .006 |

| Yes | 404 (62.1%) | 275 (58.8%) | 129 (70.5%) | |

| Brain MRI | ||||

| No | 597 (693.7%) | 439 (95.2%) | 158 (89.8%) | .011 |

| Yes | 40 (6.3%) | 22 (4.8%) | 18 (10.2%) | |

| EEG | ||||

| No | 494 (76.7%) | 377 (81.6%) | 117 (64.3%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 150 (23.3%) | 85 (18.4%) | 65 (35.7%) | |

| Lumbar puncture | ||||

| No | 592 (93.2%) | 440 (96.1%) | 152 (85.9%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 43 (6.8%) | 18 (3.9%) | 25 (14.1%) | |

| Emergency pharmacological treatment | ||||

| Benzodiazepines | ||||

| No | 538 (81%) | 416 (87%) | 122 (65.6%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 126 (19%) | 62 (13%) | 64 (34.4%) | |

| Other AEDs | ||||

| No | 313 (47.1%) | 256 (53.6%) | 57 (30.6%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 351 (52.9%) | 222 (46.4%) | 129 (69.4%) | |

| Management-related factors | ||||

| Consultation with neurology department | ||||

| No | 241 (36.3%) | 201 (42.1%) | 40 (21.5%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 423 (63.7%) | 277 (57.9%) | 146 (78.5%) | |

| Duration of stay at HED (hours) | ||||

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 12 (7−22) | 12 (7−20) | 15 (7−24) | .018 |

| Prolonged stay (observation, > 24h) | 93 (14.0%) | 56 (11.7%) | 37 (19.9%) | .006 |

| Destination at discharge | ||||

| Home | 527 (79.4%) | 407 (85.2%) | 115 (61.8%) | |

| Neurology ward | 51 (7.7%) | 24 (5%) | 27 (14.5%) | <.001 |

| Other hospital ward | 70 (10.5%) | 45 (9.4%) | 25 (13.4%) | |

| Intensive care unit | 15 (2.3%) | 2 (0.4%) | 13 (7%) | |

| Death at HED | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.05%) | |

| Management | ||||

| Management by HEDa | ||||

| No | 567 (85.8%) | 434 (91%) | 133 (72.3%) | <.001 |

| Yes | 94 (14.2%) | 43 (9%) | 51 (27.7%) | |

AED: antiepileptic drug; CT: computed tomography; EEG: electroencephalography; HED: hospital emergency department; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Therefore, patients with seizure clusters or SE were more frequently managed by PES (OR: 2.89; 95% CI, 1.91−4.36; P<.001) and especially by the HED (OR: 4.41; 95% CI, 2.69−7.22; P<.001) than patients with isolated seizures. The effect of management by PES and by the HED is shown in Table 5.

Effect of management by prehospital emergency services and hospital emergency departments in patients with seizure clusters or status epilepticus in the univariate analysis.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Management by PES | 2.89 | 1.91−4.36 | < .001 |

| Management by HED | 4.41 | 2.69−7.22 | < .001 |

95% CI: confidence interval; HED: hospital emergency department; OR: odds ratio; PES: prehospital emergency services.

This study presents a predictive model that may be useful in identifying adults at risk of developing seizure clusters or SE at the HED.

At least one in 4 patients with seizures presented seizure clusters or SE. This high rate is consistent with those reported in previous studies.1,8

This predictive model is novel as it includes not only SE but also seizure clusters. It may be useful both for PES and for HEDs as it includes simple clinical variables, such as high comorbidity burden, habitual use of at least 2 AEDs, and focal seizure semiology.

In a recent consensus document on the treatment of epileptic seizures in the HED, a seizure is regarded as a medical emergency if it presents in the form of seizure clusters, SE, or in isolation but associated with high-risk characteristics, such as first seizure, pregnancy or childhood, poor treatment adherence (>24h without taking the medication), fever, severe psychiatric comorbidities, and other complications associated with the seizure.10 According to our results, a high comorbidity burden and frequent treatment with at least 2 AEDs (suggestive of drug-resistant epilepsy11) may also be regarded as a risk factor for high-risk epilepsy. Drug-resistant epilepsy may be defined as the persistence of epileptic seizures, at a frequency that interferes with daily living activities, despite treatment with 2 AEDs at the maximum tolerated dose for a minimum of 2 years.

The ADAN scale is a novel, highly valuable tool that helps to predict the risk of presenting SE, especially for use by PES.9 It includes the following variables: speech/language alterations, eye deviation lasting >5minutes, automatism, and number of motor seizures in the previous 12hours. These variables reflect the possibility of focal-onset seizures. The scale also regards seizure clusters as a risk factor for SE. In the present study, we did not specifically gather data on these clinical variables or on whether patients with SE had previously presented seizure clusters.

Diagnosis of SE at the HED has recently been associated with higher ADAN scale scores, which confers greater validity to this scale, and with history of drug-resistant epilepsy,12 supporting the prognostic value of treatment with ≥ 2 AEDs in association with poor seizure control and impact on daily living activities.

The Status Epilepticus Severity Score (STESS) also helps to predict survival at discharge in patients with SE.13 The modified version (mSTESS)14 includes the variables level of consciousness, seizure type, age > 70 years, history of epilepsy, and level of disability according to the modified Rankin Scale. We did not evaluate the risk of in-hospital mortality; in fact, only one patient died at the HED. Age and dependence are associated with increased risk of seizure clusters or SE, although the association is neither statistically significant nor independent. In a recent study, age ≥ 75 years was not associated with higher risk of management at the HED or with poorer outcomes at discharge.15

Lastly, we should mention the RACESUR model, which is based on a subanalysis of the ACESUR registry; this is a prognostic tool for identifying adults with epileptic seizures discharged from the HED who present a high risk of adverse events at 30 days from discharge. It includes the variables generalised non-convulsive tonic-clonic seizures, treatment with ≥ 3 medications, and visiting the HED for any reason in the previous 6 months.16 This study does not specifically assess the usefulness of the RACESUR model for predicting seizure clusters or SE, but we may hypothesise that it is not a suitable tool for this purpose, since the variable visiting the HED in the previous 6 months was not found to be associated with increased risk, and the number of AEDs, rather than the total number of medications, was the variable predicting seizure clusters or SE.

According to our data, over half of patients with epileptic seizures diagnosed at the HED were attended by PES. Likewise, the patients attended at home by PES presented greater risk of seizure clusters or SE. Pharmacological treatment was more frequently prescribed to patients with seizure clusters or SE, although prescription remains limited and probably at lower levels than desirable. The risk of respiratory complications upon arrival of the ambulance at the HED is higher in patients not receiving pharmacological treatment.17

At the HED, patients with seizure clusters or SE were more frequently assigned a triage category I-II and used more diagnostic and treatment resources. Consultations with the on-call neurologist are frequent in the healthcare centres where an on-call service is available12 and in more complex cases.4

Treatment was more frequently administered by the HED than by PES. In this regard, treatment delay and inadequate dosing are associated with poorer results. Every one-minute delay in treatment is associated with a 5% increase in the cumulative risk of refractory SE18 and neurological sequelae at 4 years.19 According to the literature, however, only 13% of patients attended by their families20 and 20% of those attended by the HED21 receive benzodiazepines; these results are similar to our own.

A recent consensus document10 proposes early dual therapy not only for patients with SE but also for those presenting seizure clusters; this implies a more proactive approach both on the part of the HED and on the part of families and caregivers.8 Likewise, another recent study reported better short-term outcomes22 with appropriate preventive treatment1 at the HED.

Our study has the limitations inherent to observational, prospective, multicentre cohort studies. Firstly, opportunity sampling may have led to a selection bias, potentially including patients with pseudoseizures. Furthermore, the capacity of the model is moderate, though similar to that of other recently published models.16 We may have excluded some relevant variables; future studies should seek to include these in the model with a view to improving its predictive capacity. Lastly, external validation of the results was not performed.

In conclusion, this risk model (focal seizures, high comorbidity burden, ≥ 2 AEDs) may be helpful in stratifying the prognosis of adults with epileptic seizures attended by PES and at the HED, as it predicts the risk of presenting seizure clusters and SE. Furthermore, in our sample these patients were more frequently managed by PES, and especially by the HED, than adult patients with isolated seizures.

Future studies should seek to conduct an external validation of this model, with a view to establishing the profile of patients at risk of high-risk epileptic seizures who would benefit the most from management strategies aimed at improving outcomes. Collaboration between HED physicians, neurologists, and other specialists is essential to this end.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Other main researchers: Díaz Najera, Esther (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid; member of the SEMES Neuro-ICTUS group); García Loaiza, Juan Esteban (Hospital Universitario Guadalajara, Guadalajara); Zuabi García, Laila Belén (Hospital Son Llatzer, Palma de Mallorca); Castro Arias, Lorena (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid); Benito Lozano, Miguel (Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife); Rodríguez Maroto, Otilia (Hospital Universitario Cabueñes, Gijón); Rodríguez Borrego, Ramón (Hospital Universitario Clínico de Salamanca, Salamanca); Martínez Álvarez, Susana (Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid); Jiménez Díaz, Gregorio (Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid); Aguilar Mulet, J. Mariano (Hospital Universitario La Princesa, Madrid); Romero Pareja, Rodolfo (Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Madrid); Piñera Salmerón, Pascual (Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía, Murcia); Lindo Noriego, Ariel Rubén (Hospital General de Villarobledo, Albacete), Behzadi Koochani, Navid (Medical Emergency Service of Madrid, SUMMA).

Collaborators: Sánchez Pérez, María (Hospital Universitario Clínico de San Carlos, Madrid); Gonzalvo Navarro, Marta (Hospital Universitario Clínico de San Carlos, Madrid); Llano Hernández, Keila (Hospital Universitario Clínico de San Carlos, Madrid); Molina Medina, Araceli (Hospital Virgen de la Luz, Cuenca); Prieto Gañan, Luis Miguel (Hospital Virgen de la Luz, Cuenca); del Pozo Vega, Carlos (Hospital Universitario Clínico de Valladolid, Valladolid); del Amo Diego, Sonia (Hospital Universitario Clínico de Valladolid, Valladolid); de Francisco Andrés, Susana (Hospital Universitario Clínico de Valladolid, Valladolid); Pineda Martínez, Andrés (Hospital Neurotraumatológico Virgen de las Nieves, Granada; member of the SEMES Neuro-ICTUS group); Herrer Castejón, Ana (Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza); del Río Ibáñez, Roberto (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid); Alonso Blas, Carlos (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid); Dávila Martiarena, Aitor (Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid); Domingo Serrano, Félix (Hospital Universitario Guadalajara, Guadalajara); Fernández Escribano, M. Mercedes (Hospital Universitario Guadalajara, Guadalajara); Lozano García, Pilar (Hospital Universitario Guadalajara, Guadalajara); Ribas Estarellas, Joana (Hospital Son Llatzer, Palma de Mallorca); García Herrera, Nuria (Hospital Son Llatzer, Palma de Mallorca); Juan Juan, Margarita (Hospital Son Llatzer, Palma de Mallorca); García Marín, Alicia Paloma (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid); Muro Fernández de Pinedo, Eva (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid); Jurado Sánchez, M. Agustina (Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife); Viera Rodríguez, Natalia (Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife); Menendez García-Talavera, M. Mercedes (Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife); Casanueva Gutiérrez, Mercedes (Hospital Universitario Cabueñes, Gijón); Corominas Sánchez, Macarena (Hospital Universitario Cabueñes, Gijón); Gonzalez García, Blanca (Hospital Universitario Cabueñes, Gijón); Corbacho Cambero, Isabel (Hospital Universitario Clínico de Salamanca, Salamanca); Gómez Prieto, Agustín (Hospital Universitario Clínico de Salamanca, Salamanca); Naranjo Armenteros, Javier (Hospital Universitario Clínico de Salamanca, Salamanca); Cobo Mora, Julio (Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid); Muriel Patino, Eva (Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid); Martínez Villena, Beatriz (Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid); Vaamonde Paniagua, Catuxa (Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid); Carrasco Rodriguez, M. Isabel (Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid); Santiago Poveda, Cristina (Hospital Universitario La Princesa, Madrid); Contreras Murillo, Elvira (Hospital Universitario La Princesa, Madrid); Val de Santos, Francisco Javier (Hospital Universitario La Princesa, Madrid); Álvarez Rodríguez, Virginia (Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Madrid); Merlo Loranca, Marta (Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Madrid); Olalla Martín, Victoria (Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Madrid); Villa Zamora, Blanca (Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía, Murcia); Tomás Jiménez, Esther (Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía, Murcia; member of the SEMES Neuro-ICTUS group); Ramirez, Laura; Fuentes, Gonzalo (Hospital General de Villarobledo, Albacete); Sánchez Rocamora, Juan Luis (Hospital General de Villarobledo, Albacete); Muñoz Isabel, Belén (Medical Emergency Service of Madrid, SUMMA); González León, Manuel José (Medical Emergency Service of Madrid, SUMMA); Sánchez Ortega, Antonio (Medical Emergency Service of Madrid, SUMMA).