There is a need for clinically administered instruments capable of detecting executive dysfunction in dementia.

ObjectiveThe translation and validation of Executive Battery 25 (EB25) and a short version for screening of executive dysfunction in dementia.

MethodsThe original battery was translated and validated using convergent and divergent correlation in 66 mild dementia patients (CDR 1) matched with 66 controls. EB25 consists of 25 items which detect executive dysfunction. Convergent correlation was made with 7 tests assessing executive dysfunction, the Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe) and Disability Fast Assessment Scale.

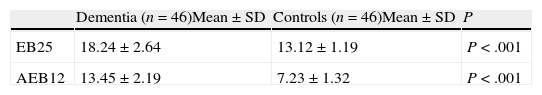

ResultsPatients had higher scores than controls and correlated with the Stroop Test, verbal fluency test and Frontal Behaviour Inventory. Only 12 out of 25 items were needed to separate both groups, which were used to build an abbreviated Executive Battery with equal psychometric properties and discriminative power. The cut-off point for EB25 was 12, and 7 for the abbreviated version. A cut-off point of 12 was able to discriminate between ‘Alzheimer's disease’ (AD) and frontotemporal lobe dementia (FTLD).

ConclusionsEB25 and AEB12 enable executive dysfunction to be detected in mild dementia. On the other hand, AEB12 exhibits better psychometric properties than the original battery, allowing discrimination between AD and FTLD and is completed in less time.

Se necesitan instrumentos que detecten disfunción ejecutiva en demencias y que puedan ser administrados clínicamente.

ObjetivosTraducción y validación de la batería ejecutiva 25 (BE25) y versión abreviada (BEA12) para detección de disfunción ejecutiva en demencia.

Material y métodosSe tradujo la batería original y se validó mediante correlación convergente y divergente en 66 pacientes con demencia leve (CDR 1) apareados con 66 controles. La batería ejecutiva 25 (BE25) está compuesta por 25 ítems que detectan disfunción ejecutiva. La correlación convergente se realizó con 7 tests de disfunción ejecutiva, la Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe) y la escala de evaluación rápida de la discapacidad (EERD-2).

ResultadosLos pacientes tuvieron mayores puntajes que controles y correlacionaron con test de Stroop, fluencia verbal, Frontal System Behavior Scale, Winsconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) y Trail Making Test parte B (TMT-B). De los 25 ítems, 12 son suficientes para separar los grupos. Con esos 12 ítems se construyó una batería ejecutiva abreviada (BEA12) que exhibió similares propiedades psicométricas y capacidad de discriminación entre DA y DFT. El punto de corte para BE25 fue 15, para BEA12 de 7 y un punto de corte de 12 permitió discriminar entre DA y DFT.

ConclusionesBE25 y BEA12 permiten detectar disfunción ejecutiva en demencia leve y representa un instrumento confiable para evaluar disfunción ejecutiva en demencia. Por otra parte, la BEA12 exhibe mejores propiedades psicométricas que la batería original, permite discriminar entre DA y DFT y se completa en menor tiempo.

Executive functions are an array of abilities that are necessary for planning and regulating complex goal-driven behavior, including assessing social appropriateness, empathy, and the ability to anticipate the consequences of actions. In descriptive terms, the executive functions may be divided into different components, such as initiative, planning, organizing, maintenance, and self-regulation of performance.1,2 They are associated with the prefrontal cortex and the thalamo-frontal connections. Injury to this area may elicit socially inappropriate behavior, lack of initiative, adhering to routines in the face of change, lack of empathy, and inability to predict consequences of actions. Doctors increasingly recognize the presence of a certain level of executive dysfunction in dementia in general and in Alzheimer in particular, although it is not exclusively limited to the latter.3 Executive dysfunction severity is associated with functional impairment, an increased need for care, and development of neuropsychiatric symptoms.4,5 Although executive dysfunction is a frequent feature of Alzheimer disease, not all dementia scales measure executive function; the MMSE and ADAS, for example, do not.6 Executive function is normally examined using neuropsychological tests that are designed to assess specific components, such as interference suppression (Stroop color/word test, Semantic Interference Test), set-shifting (Wisconsin card-sorting test), divided attention (Trail Making Test, part B), and mental flexibility (Word Fluency test). Although a number of instruments have acceptable diagnostic properties and statistics,7 not all of them were designed specifically to evaluate executive function. Some have unacceptable psychometric properties,8 while others have a relatively lengthy administration time,9 variable levels of sensitivity and specificity,10 results that have not been replicated by later studies,11 or no proved predictive ability for distinguishing between different types of dementia.12 Other instruments, such as BADS13 or the Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe)14 and its Spanish version15 have not been used in populations with dementia. The Frontal Assessment Battery16 is a widely-used screening instrument with 6 subtests that evaluate conceptualisation, cognitive flexibility, motor programming, sensitivity to interference, inhibitory control, and prehension behavior. Although it is described as suitable for distinguishing between executive dysfunctions corresponding to different neurological diseases and the test is easy to administer, questions remain about whether it can evaluate frontal function exclusively. On the other hand, the EXIT 25 test17,18 has been applied in both non-clinical populations19,20 and clinical populations.12,21,22 Brief versions have also been validated in other languages23,24 and provide normative data and cut-off points in different populations. For these reasons, a Spanish-language version of the test is an attractive prospect. As the number of patients referred for early assessment of dementia increases, we also find increased demand for early detection instruments that are easy to administer, show a high predictive capacity for executive dysfunction, and measure functional capacity. The Executive Interview (EXIT 25) is a screening instrument that was developed to assess executive dysfunction.25 It evaluates an array of domains including perseveration, imitation, echopraxia, echolalia, intrusions, frontal liberation signs, lack of spontaneity, disinhibition, and utilization behavior. This test may be administered by doctors or trained healthcare professionals in different settings. Maximum completion time for subjects with no cognitive changes is 15minutes. Most of the studies using EXIT 25 have included large populations of elderly adults. The test has been shown to have high discriminant ability in subjects with care needs and those without care needs who are at risk for being institutionalized. It has also been associated with poor performance of activities of daily living in healthy elderly adults. The test has high internal consistency (α=0.85) and inter-rater reliability (r=0.91). It correlates with WCST categories (r=0.54), TMT-B (r=0.64), Sustained Attention Test (Time, r=0.82; Errors, r=0.83) and the Lezak test (r=0.57). As a result, EXIT 25 is a valuable instrument for clinical use in mild to moderate stages of dementia.26,27

Objectives- 1.

Translate EXIT 25 and validate the result (EB25) in a sample of patients with mild dementia (CDR 1) to evaluate its accuracy as a dementia screening instrument.

- 2.

Determine the cut-off point and predictive power for functional disability.

- 3.

Establish correlations with other executive function tests.

- 4.

Validate a brief 12-item version (AEB12) for assessing progression of executive dysfunction in dementia, especially in AD and FTD.

The sample size was set to detect an effect size of 0.7 (Cohen's D), which yielded a required sample size of 40. We then recruited 66 patients with mild dementia who were attended at a community health outpatient center. The sample included all referred patients, in consecutive order, who were older than 60 and who scored 20 or higher on the Lobo MEC test. Controls were selected from among a cohort of age- and education-matched volunteers. Inclusion criteria were age over 60 with a Lobo MEC score>20 and mild dementia (CDR 1). None of the patients presented comorbidities that would affect their cognitive states (depression, alcoholism, drug abuse, history of head trauma with/without loss of consciousness, history of stroke, or sensorimotor deficits such as visual or auditory deficit or paralysis). Under the guidance of a psychiatrist independent from the investigation, patients underwent a complete examination with neurological, psychiatric, and neuropsychiatric components; laboratory analyses; MR spectroscopy; and CT. After these steps had been completed, patients were classified based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for dementia.28 According to these criteria, 26 patients were diagnosed with Alzheimer disease (AD),29 12 with vascular dementia (VD),30 4 with mixed dementia (MD), 23 with frontotemporal dementia (FTD),31 and 1 with non-specific dementia (NSD). All patients completed the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),32 an instrument evaluating 18 symptoms including hostility, suspiciousness, hallucinations, and grandiosity. Their scores depended on the doctor's evaluation during the interview and on behavior observed in the preceding week. Scores range from 1 to 7 according to the extent of impairment of the component in question (emotion, thought, positive and negative symptoms, behavior, and initiation), evaluating typical aspects of frontal lobe function. The global cognitive evaluation was completed using Lobo's MEC test,33 the CDR,34 and the NEUROPSI test battery.35 NEUROPSI is a brief neuropsychological instrument adapted for Spanish-speaking populations. It contains the following sections: 1. Time-space and personal orientation (27 points); 2. Attention (27 points) (reverse digit span, visual detection, sequenced subtraction), 3. Encoding (18) (verbal memory and semi-complex figure); 4. Language (26) (naming, word repetition, comprehension, semantic and phonological word fluency); 5. Reading (2); 6. Writing (2); 7. Conceptual function (10) (similarities, arithmetic, and sequences); 8. Motor function (8) (changes in hand position, alternating movements, and opposite reactions); 9. Recall (30) (spontaneous or clued recall, recognition, recall of semi-complex figure). Testing yielded a total of 26 sets of results with a high score of 130 points. Behavioral changes were evaluated with the Frontal System Behavior Scale (FrSBe)14 and the Rapid Disability Rating Scale (RDRS-2).36 FrSBe is a scale with 46 items, divided into 3 subscales derived from factor analysis: apathy (FrSBe-a), disinhibition (FrSBe-d), and executive dysfunction (FrSBe-e), plus a total score (FrSBe-t). Answers are given on a 5-point Likert scale (1=almost never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=frequently, 5=almost always). Items 1 through 32 examine prefrontal function deficits, with higher scores indicating more severe conditions. Items 33 through 46 explore executive function, with lower scores indicating more severe conditions. FrSBe has shown high internal consistency in clinical and normal populations. It has been validated in populations with neuropsychological diseases including prefrontal and subcortical dysfunction. Despite the test being subjective and self-administered, it has demonstrated high diagnostic validity in clinical samples and compared to neuropsychological tests for executive functions. RDRS-2 is a multidimensional instrument used as a quick assessment of disability in elderly adult patients. It consists of 18 questions distributed in 3 subscales. The first subscale includes 8 questions aimed at determining the degree of help the patient needs for activities of daily life. The subscale includes 7 items for basic activities like eating, walking, or getting dressed, and one item for instrumental or adaptive activities such as managing money, using the telephone, or shopping. The second subscale measures the degree of disability due to changes in 3 interactive capabilities (communication, hearing, and sight). It also evaluates the patient's need for assistance with food, medication, incontinence, or lack of mobility. The third and last subscale evaluates 3 neuropsychiatric problems that can affect the other scales: confusion, lack of cooperation, and depression. There are 4 response options: (a) no help needed, (b) needs some help, (c) needs substantial assistance, and (d) completely dependent. Scores range from 18 to 72 points. The higher the score, the higher the degree of disability. The last test was EXIT 25 (Appendix A),17 consisting of 25 items or brief tasks that can reveal executive dysfunctions. The instructions given to patients for each task were minimal to discourage analysis and discover any latent signs of disinhibition. This instrument was translated to Spanish and then back to English by two different translators working independently. The sentences in section 4 (anomalous sentence repetition) were modified semantically as follows: Yo juro ser fiel a la bandera; María alimentó a un pequeño cordero; Una puntada a tiempo salva cientos de vidas; Titila, titila pequeña estrellita. The three words given in section 6 (memory/distraction) appeared as libro, árbol, and casa, and the word ‘brown’ in section 7 (interference task) was changed to marrón. The final result was evaluated by 2 expert psychiatrists who coincided on all points.37 Scores ranged from 0 to 50, with high scores indicating executive dysfunction. Scores of 15 or higher were markers of clinically important executive function impairment. To test convergent validity, we selected 7 tests recognised for their ability to identify executive functions. Their main limitations were lack of validation in Spanish in some cases, or that the tests represented only partial or limited aspects of the executive function construct. We registered total time and number of errors in a maximum of 500seconds on the Trail Making Test B (TMT-B).38 The Stroop test39 registered the time for the incongruent phase up to a maximum of 360seconds if the patient was unable to complete the test. We recorded the number of errors on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST)40; patients who were unable to complete the test were assigned a baseline level of 36 errors. The categorical word fluency test41 recorded the maximum number of animals named in one minute. The lexical word fluency test42 recorded the number of words beginning with ‘P’ the patient was able to name. For design fluency,43 examiners recorded the number of different designs created in 4minutes, excluding scribbles and drawings that could be named. Direct values were recorded for the ‘similarities’ section on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.44

Statistical methodsThe purpose of this transversal, descriptive study was to validate EB25, a Spanish-language version of EXIT 25. Construct validity was determined through convergent validity analysis. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare non-ordinal values. The items in the test battery were tested for homogeneity (internal consistency) using Cronbach's alpha. Inter-rater reliability was evaluated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). We used Pearson's r to compute the convergent construct validity between EB25 and the TMT-B, Stroop test, WCST, categorical word fluency, lexical word fluency, analogies, FrSBe, RDRS-2, and MEC. We were aware that patients with dementia and behavioural disorders typically show poorer executive abilities, increased behavioral problems (FrSBe9), and increased dependence for activities of daily living (RDRS-2). The remaining values were calculated according to the rest of the answers to test battery items. Divergent validity was evaluated using NEUROPSI. Controls and patients were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post hoc Bonferroni correction. Controls were distinguished from patients with AD or FTD by the ANOVA test and a stepwise multivariate logistic regression. EB25 and AEB12's ability to discriminate between controls and patients was determined by analysing ROC curves. We used Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Statistical analysis was completed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 15.0. Values of P<.01 were considered statistically significant.

ProcedureNeuropsychological tests were administered to controls in a single session. An expert neurologist administered the Lobo MEC, RDRS-2, FrSB3, and CDR tests. This neurologist was unaware of the patient's results on EB25 and the neuropsychological tests. Meanwhile, an additional two independent neuropsychologists who were blinded to EB25 results administered the remaining neuropsychological tests on different days. Test results did not change the type or the grade of dementia that had been established previously. One of the psychiatrists administered EB25 to both controls and patients in a single session (t1), while a second psychiatrist administered the same instrument during a second visit 2 weeks later (t2). To evaluate test–retest reliability, the first psychiatrist administered EB25 to a subgroup of patients (n=25) a week after the first interview.

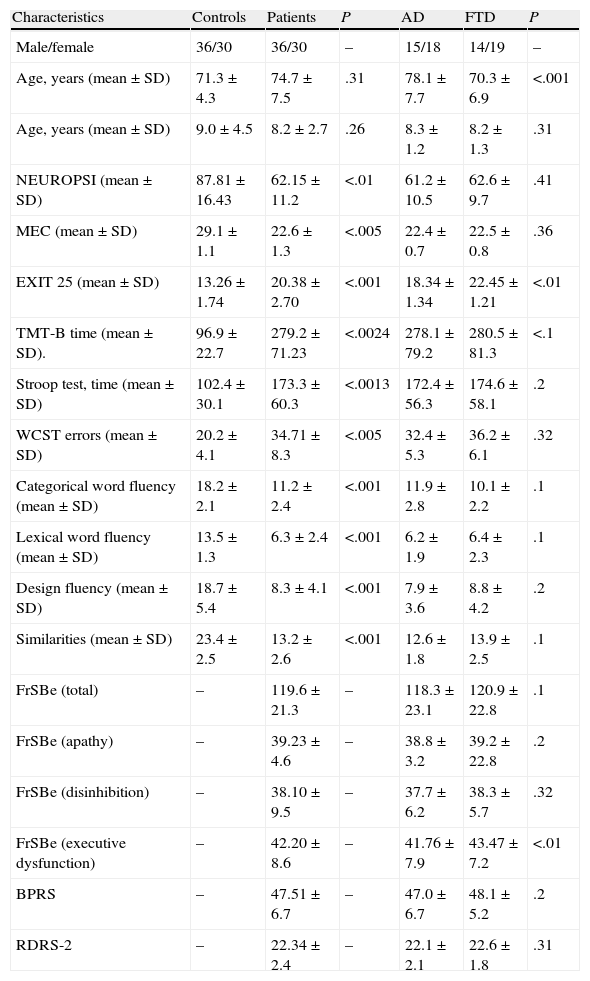

ResultsDemographic data and results from the different neuropsychological tests are shown in Table 1.

Demographic data and test results.

| Characteristics | Controls | Patients | P | AD | FTD | P |

| Male/female | 36/30 | 36/30 | – | 15/18 | 14/19 | – |

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 71.3±4.3 | 74.7±7.5 | .31 | 78.1±7.7 | 70.3±6.9 | <.001 |

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 9.0±4.5 | 8.2±2.7 | .26 | 8.3±1.2 | 8.2±1.3 | .31 |

| NEUROPSI (mean±SD) | 87.81±16.43 | 62.15±11.2 | <.01 | 61.2±10.5 | 62.6±9.7 | .41 |

| MEC (mean±SD) | 29.1±1.1 | 22.6±1.3 | <.005 | 22.4±0.7 | 22.5±0.8 | .36 |

| EXIT 25 (mean±SD) | 13.26±1.74 | 20.38±2.70 | <.001 | 18.34±1.34 | 22.45±1.21 | <.01 |

| TMT-B time (mean±SD). | 96.9±22.7 | 279.2±71.23 | <.0024 | 278.1±79.2 | 280.5±81.3 | <.1 |

| Stroop test, time (mean±SD) | 102.4±30.1 | 173.3±60.3 | <.0013 | 172.4±56.3 | 174.6±58.1 | .2 |

| WCST errors (mean±SD) | 20.2±4.1 | 34.71±8.3 | <.005 | 32.4±5.3 | 36.2±6.1 | .32 |

| Categorical word fluency (mean±SD) | 18.2±2.1 | 11.2±2.4 | <.001 | 11.9±2.8 | 10.1±2.2 | .1 |

| Lexical word fluency (mean±SD) | 13.5±1.3 | 6.3±2.4 | <.001 | 6.2±1.9 | 6.4±2.3 | .1 |

| Design fluency (mean±SD) | 18.7±5.4 | 8.3±4.1 | <.001 | 7.9±3.6 | 8.8±4.2 | .2 |

| Similarities (mean±SD) | 23.4±2.5 | 13.2±2.6 | <.001 | 12.6±1.8 | 13.9±2.5 | .1 |

| FrSBe (total) | – | 119.6±21.3 | – | 118.3±23.1 | 120.9±22.8 | .1 |

| FrSBe (apathy) | – | 39.23±4.6 | – | 38.8±3.2 | 39.2±22.8 | .2 |

| FrSBe (disinhibition) | – | 38.10±9.5 | – | 37.7±6.2 | 38.3±5.7 | .32 |

| FrSBe (executive dysfunction) | – | 42.20±8.6 | – | 41.76±7.9 | 43.47±7.2 | <.01 |

| BPRS | – | 47.51±6.7 | – | 47.0±6.7 | 48.1±5.2 | .2 |

| RDRS-2 | – | 22.34±2.4 | – | 22.1±2.1 | 22.6±1.8 | .31 |

EB25, Executive Interview 25; RDRS-2, Rapid Disability Rating Scale-2; FrSBe, Frontal Systems Behavior Scale; MEC, Lobo's Mini Examen Cognoscitivo; TMT-B, Trail Making Test B; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

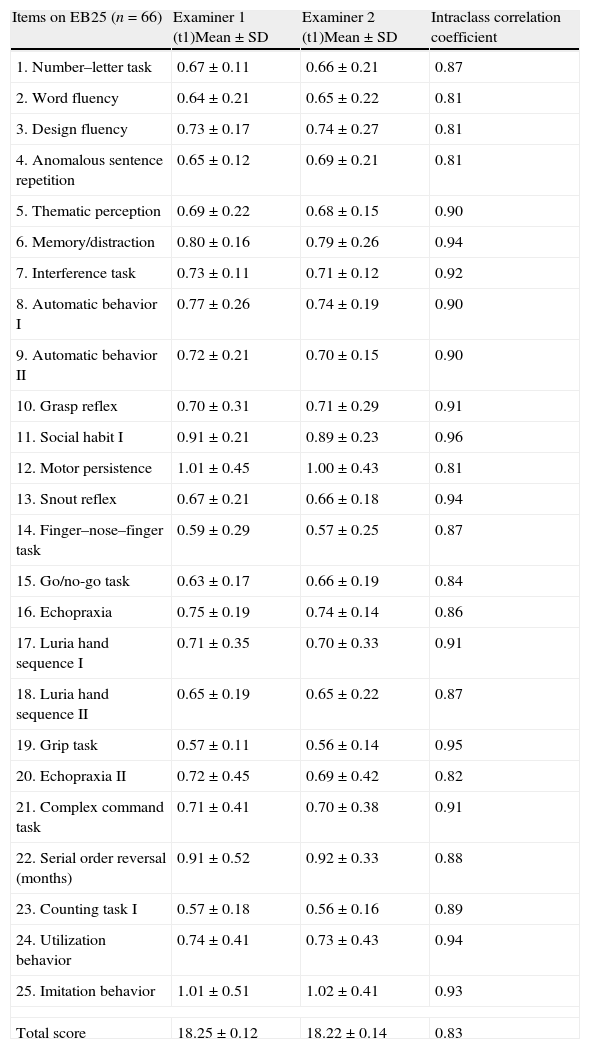

Statistical analysis using the Mann–Whitney test did not find any sex differences in the EB25 results (Z=0.080, P=.43). When controlled by sex and age, EB25 showed a negative correlation to years of education (r=−0.23; P<.001). When controlled by sex and years of education, however, it was positively correlated to age (r=0.67; P=.015). There were age differences between patients with AD and FTD (67.10±1.02 vs 73.9±1.3, P=.002). Testing found high levels of internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=0.87), test–retest reliability (ICC=0.89; 95% CI, 0.76–0.91), and inter-rater reliability calculated using repeated measures ANOVA for the total score and for each separate item (ICC=0.94) (Table 2).

Inter-evaluator reliability measured by the intraclass correlation of EB25 items.

| Items on EB25 (n=66) | Examiner 1 (t1)Mean±SD | Examiner 2 (t1)Mean±SD | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| 1. Number–letter task | 0.67±0.11 | 0.66±0.21 | 0.87 |

| 2. Word fluency | 0.64±0.21 | 0.65±0.22 | 0.81 |

| 3. Design fluency | 0.73±0.17 | 0.74±0.27 | 0.81 |

| 4. Anomalous sentence repetition | 0.65±0.12 | 0.69±0.21 | 0.81 |

| 5. Thematic perception | 0.69±0.22 | 0.68±0.15 | 0.90 |

| 6. Memory/distraction | 0.80±0.16 | 0.79±0.26 | 0.94 |

| 7. Interference task | 0.73±0.11 | 0.71±0.12 | 0.92 |

| 8. Automatic behavior I | 0.77±0.26 | 0.74±0.19 | 0.90 |

| 9. Automatic behavior II | 0.72±0.21 | 0.70±0.15 | 0.90 |

| 10. Grasp reflex | 0.70±0.31 | 0.71±0.29 | 0.91 |

| 11. Social habit I | 0.91±0.21 | 0.89±0.23 | 0.96 |

| 12. Motor persistence | 1.01±0.45 | 1.00±0.43 | 0.81 |

| 13. Snout reflex | 0.67±0.21 | 0.66±0.18 | 0.94 |

| 14. Finger–nose–finger task | 0.59±0.29 | 0.57±0.25 | 0.87 |

| 15. Go/no-go task | 0.63±0.17 | 0.66±0.19 | 0.84 |

| 16. Echopraxia | 0.75±0.19 | 0.74±0.14 | 0.86 |

| 17. Luria hand sequence I | 0.71±0.35 | 0.70±0.33 | 0.91 |

| 18. Luria hand sequence II | 0.65±0.19 | 0.65±0.22 | 0.87 |

| 19. Grip task | 0.57±0.11 | 0.56±0.14 | 0.95 |

| 20. Echopraxia II | 0.72±0.45 | 0.69±0.42 | 0.82 |

| 21. Complex command task | 0.71±0.41 | 0.70±0.38 | 0.91 |

| 22. Serial order reversal (months) | 0.91±0.52 | 0.92±0.33 | 0.88 |

| 23. Counting task I | 0.57±0.18 | 0.56±0.16 | 0.89 |

| 24. Utilization behavior | 0.74±0.41 | 0.73±0.43 | 0.94 |

| 25. Imitation behavior | 1.01±0.51 | 1.02±0.41 | 0.93 |

| Total score | 18.25±0.12 | 18.22±0.14 | 0.83 |

Statistics from items in EB25 are described in Table 3.

Statistical values of items on EB25.

| Items on EB25 (n=66) | Mean±SD | Mean without item | Variance without item | Corrected item-total correlation | Without item |

| Number–letter task | 0.67±0.11 | 17.58 | 79.33 | 0.57 | 0.90 |

| Word fluency | 0.64±0.21 | 17.61 | 79.36 | 0.67 | 0.90 |

| Design fluency | 0.73±0.17 | 17.52 | 79.27 | 0.56 | 0.90 |

| Anomalous sentence repetition | 0.65±0.12 | 17.60 | 79.34 | 0.64 | 0.91 |

| Thematic perception | 0.69±0.22 | 17.56 | 79.31 | 0.62 | 0.90 |

| Memory/distraction | 0.80±0.16 | 17.45 | 79.20 | 0.58 | 0.90 |

| Interference task | 0.73±0.11 | 17.52 | 79.27 | 0.62 | 0.90 |

| Automatic behavior I | 0.77±0.26 | 17.48 | 79.23 | 0.57 | 0.90 |

| Automatic behavior II | 0.72±0.21 | 17.53 | 79.28 | 0.71 | 0.91 |

| Grasp reflex | 0.70±0.31 | 17.55 | 79.30 | 0.70 | 0.90 |

| Social habit I | 0.91±0.21 | 17.34 | 79.09 | 0.68 | 0.90 |

| Motor persistence | 1.01±0.45 | 17.24 | 78.99 | 0.67 | 0.90 |

| Snout reflex | 0.67±0.21 | 17.58 | 79.33 | 0.76 | 0.91 |

| Finger–nose–finger task | 0.59±0.29 | 17.66 | 79.41 | 0.76 | 0.90 |

| Go/no-go task | 0.63±0.17 | 17.62 | 79.37 | 0.71 | 0.90 |

| Echopraxia | 0.75±0.19 | 17.50 | 79.25 | 0.56 | 0.90 |

| Luria hand sequence I | 0.71±0.35 | 17.54 | 79.29 | 0.59 | 0.90 |

| Luria hand sequence II | 0.65±0.19 | 17.59 | 79.35 | 0.65 | 0.90 |

| Grip task | 0.57±0.11 | 17.68 | 79.43 | 0.59 | 0.91 |

| Echopraxia II | 0.72±0.45 | 17.53 | 79.28 | 0.68 | 0.90 |

| Complex command task | 0.71±0.41 | 17.54 | 79.29 | 0.73 | 0.90 |

| Serial order reversal (months) | 0.91±0.52 | 17.34 | 79.09 | 0.75 | 0.91 |

| Counting task I | 0.57±0.18 | 17.68 | 79.43 | 0.71 | 0.90 |

| Utilization behavior | 0.74±0.41 | 17.51 | 79.26 | 0.56 | 0.90 |

| Imitation behavior | 1.01±0.51 | 17.24 | 78.99 | 0.59 | 0.90 |

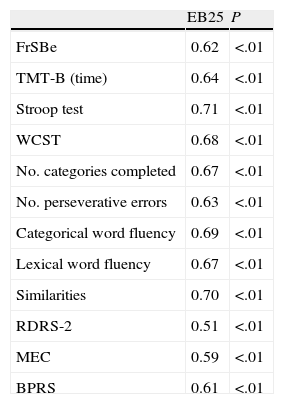

EB25 construct validity was examined using the Pearson correlation coefficient with instruments assessing executive functions and frontal behavior. Results were significant, except those from the MEC (Table 4).

Correlation between EB25, neuropsychological tests, FrSBe, and RDRS-2.

| EB25 | P | |

| FrSBe | 0.62 | <.01 |

| TMT-B (time) | 0.64 | <.01 |

| Stroop test | 0.71 | <.01 |

| WCST | 0.68 | <.01 |

| No. categories completed | 0.67 | <.01 |

| No. perseverative errors | 0.63 | <.01 |

| Categorical word fluency | 0.69 | <.01 |

| Lexical word fluency | 0.67 | <.01 |

| Similarities | 0.70 | <.01 |

| RDRS-2 | 0.51 | <.01 |

| MEC | 0.59 | <.01 |

| BPRS | 0.61 | <.01 |

BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; RDRS-2, Rapid Disability Rating Scale-2; FrSBe, Frontal Systems Behavior Scale; MEC, Lobo's Mini Examen Cognoscitivo; TMT-B, Trail Making Test B; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

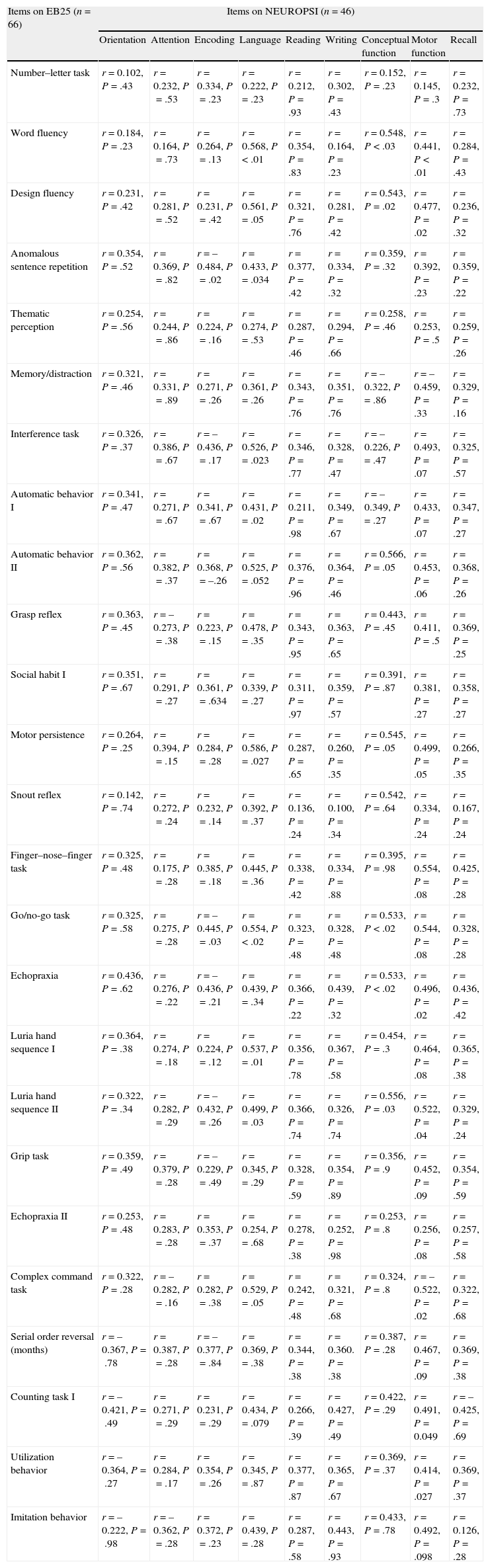

The divergent validity of EB25 was analyzed using the NEUROPSI scale; generally speaking, there were no positive correlations. This was expected, as NEUROPSI measures global cognitive functions, except for encoding, language, and motor function tasks, which share domains with executive functions (Table 5).

Divergent validity of EB25 and NEUROPSI.

| Items on EB25 (n=66) | Items on NEUROPSI (n=46) | ||||||||

| Orientation | Attention | Encoding | Language | Reading | Writing | Conceptual function | Motor function | Recall | |

| Number–letter task | r=0.102, P=.43 | r=0.232, P=.53 | r=0.334, P=.23 | r=0.222, P=.23 | r=0.212, P=.93 | r=0.302, P=.43 | r=0.152, P=.23 | r=0.145, P=.3 | r=0.232, P=.73 |

| Word fluency | r=0.184, P=.23 | r=0.164, P=.73 | r=0.264, P=.13 | r=0.568, P<.01 | r=0.354, P=.83 | r=0.164, P=.23 | r=0.548, P<.03 | r=0.441, P<.01 | r=0.284, P=.43 |

| Design fluency | r=0.231, P=.42 | r=0.281, P=.52 | r=0.231, P=.42 | r=0.561, P=.05 | r=0.321, P=.76 | r=0.281, P=.42 | r=0.543, P=.02 | r=0.477, P=.02 | r=0.236, P=.32 |

| Anomalous sentence repetition | r=0.354, P=.52 | r=0.369, P=.82 | r=–0.484, P=.02 | r=0.433, P=.034 | r=0.377, P=.42 | r=0.334, P=.32 | r=0.359, P=.32 | r=0.392, P=.23 | r=0.359, P=.22 |

| Thematic perception | r=0.254, P=.56 | r=0.244, P=.86 | r=0.224, P=.16 | r=0.274, P=.53 | r=0.287, P=.46 | r=0.294, P=.66 | r=0.258, P=.46 | r=0.253, P=.5 | r=0.259, P=.26 |

| Memory/distraction | r=0.321, P=.46 | r=0.331, P=.89 | r=0.271, P=.26 | r=0.361, P=.26 | r=0.343, P=.76 | r=0.351, P=.76 | r=–0.322, P=.86 | r=–0.459, P=.33 | r=0.329, P=.16 |

| Interference task | r=0.326, P=.37 | r=0.386, P=.67 | r=–0.436, P=.17 | r=0.526, P=.023 | r=0.346, P=.77 | r=0.328, P=.47 | r=–0.226, P=.47 | r=0.493, P=.07 | r=0.325, P=.57 |

| Automatic behavior I | r=0.341, P=.47 | r=0.271, P=.67 | r=0.341, P=.67 | r=0.431, P=.02 | r=0.211, P=.98 | r=0.349, P=.67 | r=–0.349, P=.27 | r=0.433, P=.07 | r=0.347, P=.27 |

| Automatic behavior II | r=0.362, P=.56 | r=0.382, P=.37 | r=0.368, P=–.26 | r=0.525, P=.052 | r=0.376, P=.96 | r=0.364, P=.46 | r=0.566, P=.05 | r=0.453, P=.06 | r=0.368, P=.26 |

| Grasp reflex | r=0.363, P=.45 | r=–0.273, P=.38 | r=0.223, P=.15 | r=0.478, P=.35 | r=0.343, P=.95 | r=0.363, P=.65 | r=0.443, P=.45 | r=0.411, P=.5 | r=0.369, P=.25 |

| Social habit I | r=0.351, P=.67 | r=0.291, P=.27 | r=0.361, P=.634 | r=0.339, P=.27 | r=0.311, P=.97 | r=0.359, P=.57 | r=0.391, P=.87 | r=0.381, P=.27 | r=0.358, P=.27 |

| Motor persistence | r=0.264, P=.25 | r=0.394, P=.15 | r=0.284, P=.28 | r=0.586, P=.027 | r=0.287, P=.65 | r=0.260, P=.35 | r=0.545, P=.05 | r=0.499, P=.05 | r=0.266, P=.35 |

| Snout reflex | r=0.142, P=.74 | r=0.272, P=.24 | r=0.232, P=.14 | r=0.392, P=.37 | r=0.136, P=.24 | r=0.100, P=.34 | r=0.542, P=.64 | r=0.334, P=.24 | r=0.167, P=.24 |

| Finger–nose–finger task | r=0.325, P=.48 | r=0.175, P=.28 | r=0.385, P=.18 | r=0.445, P=.36 | r=0.338, P=.42 | r=0.334, P=.88 | r=0.395, P=.98 | r=0.554, P=.08 | r=0.425, P=.28 |

| Go/no-go task | r=0.325, P=.58 | r=0.275, P=.28 | r=–0.445, P=.03 | r=0.554, P<.02 | r=0.323, P=.48 | r=0.328, P=.48 | r=0.533, P<.02 | r=0.544, P=.08 | r=0.328, P=.28 |

| Echopraxia | r=0.436, P=.62 | r=0.276, P=.22 | r=–0.436, P=.21 | r=0.439, P=.34 | r=0.366, P=.22 | r=0.439, P=.32 | r=0.533, P<.02 | r=0.496, P=.02 | r=0.436, P=.42 |

| Luria hand sequence I | r=0.364, P=.38 | r=0.274, P=.18 | r=0.224, P=.12 | r=0.537, P=.01 | r=0.356, P=.78 | r=0.367, P=.58 | r=0.454, P=.3 | r=0.464, P=.08 | r=0.365, P=.38 |

| Luria hand sequence II | r=0.322, P=.34 | r=0.282, P=.29 | r=–0.432, P=.26 | r=0.499, P=.03 | r=0.366, P=.74 | r=0.326, P=.74 | r=0.556, P=.03 | r=0.522, P=.04 | r=0.329, P=.24 |

| Grip task | r=0.359, P=.49 | r=0.379, P=.28 | r=–0.229, P=.49 | r=0.345, P=.29 | r=0.328, P=.59 | r=0.354, P=.89 | r=0.356, P=.9 | r=0.452, P=.09 | r=0.354, P=.59 |

| Echopraxia II | r=0.253, P=.48 | r=0.283, P=.28 | r=0.353, P=.37 | r=0.254, P=.68 | r=0.278, P=.38 | r=0.252, P=.98 | r=0.253, P=.8 | r=0.256, P=.08 | r=0.257, P=.58 |

| Complex command task | r=0.322, P=.28 | r=–0.282, P=.16 | r=0.282, P=.38 | r=0.529, P=.05 | r=0.242, P=.48 | r=0.321, P=.68 | r=0.324, P=.8 | r=–0.522, P=.02 | r=0.322, P=.68 |

| Serial order reversal (months) | r=–0.367, P=.78 | r=0.387, P=.28 | r=–0.377, P=.84 | r=0.369, P=.38 | r=0.344, P=.38 | r=0.360. P=.38 | r=0.387, P=.28 | r=0.467, P=.09 | r=0.369, P=.38 |

| Counting task I | r=–0.421, P=.49 | r=0.271, P=.29 | r=0.231, P=.29 | r=0.434, P=.079 | r=0.266, P=.39 | r=0.427, P=.49 | r=0.422, P=.29 | r=0.491, P=0.049 | r=–0.425, P=.69 |

| Utilization behavior | r=–0.364, P=.27 | r=0.284, P=.17 | r=0.354, P=.26 | r=0.345, P=.87 | r=0.377, P=.87 | r=0.365, P=.67 | r=0.369, P=.37 | r=0.414, P=.027 | r=0.369, P=.37 |

| Imitation behavior | r=–0.222, P=.98 | r=–0.362, P=.28 | r=0.372, P=.23 | r=0.439, P=.28 | r=0.287, P=.58 | r=0.443, P=.93 | r=0.433, P=.78 | r=0.492, P=.098 | r=0.126, P=.28 |

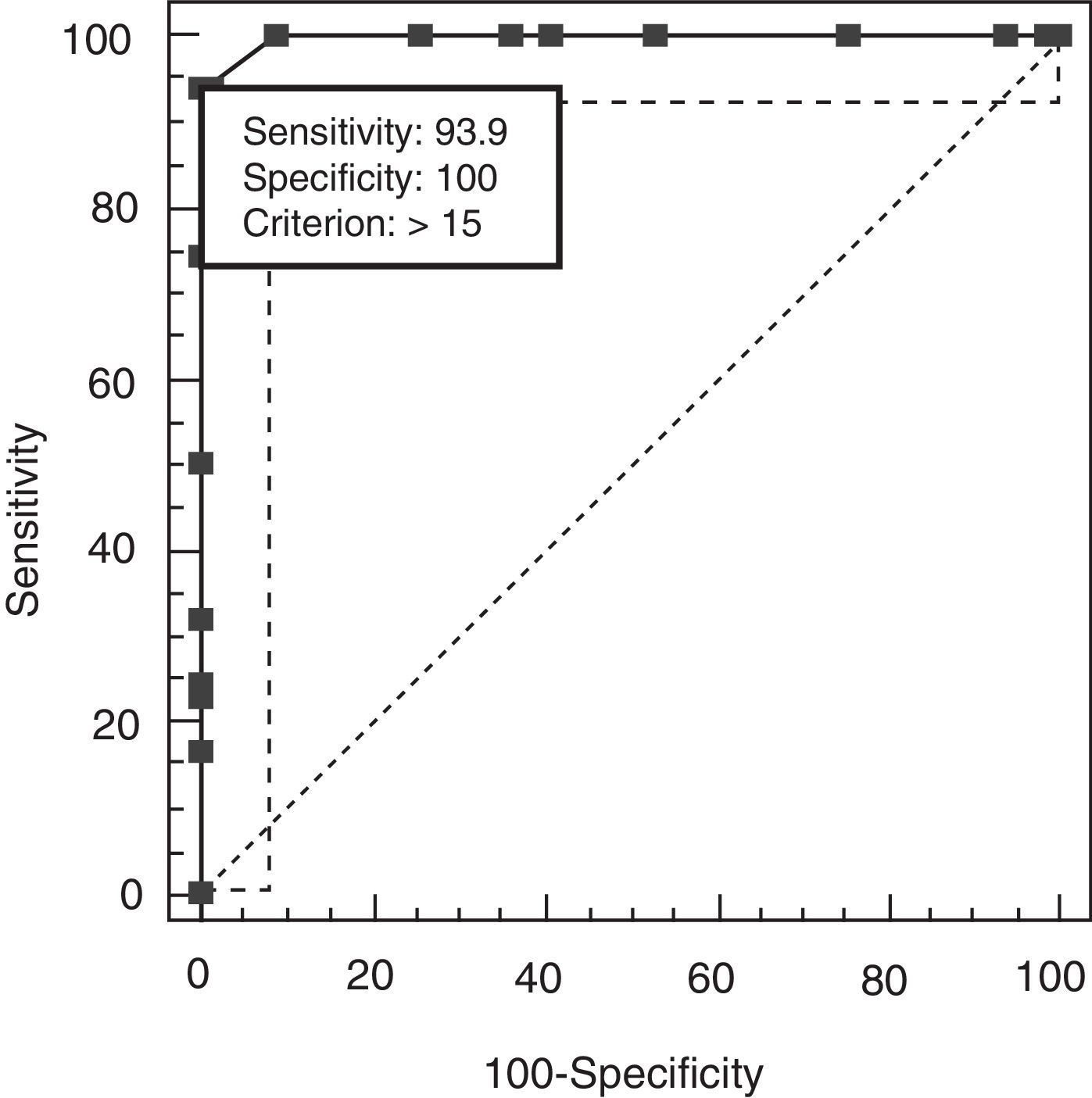

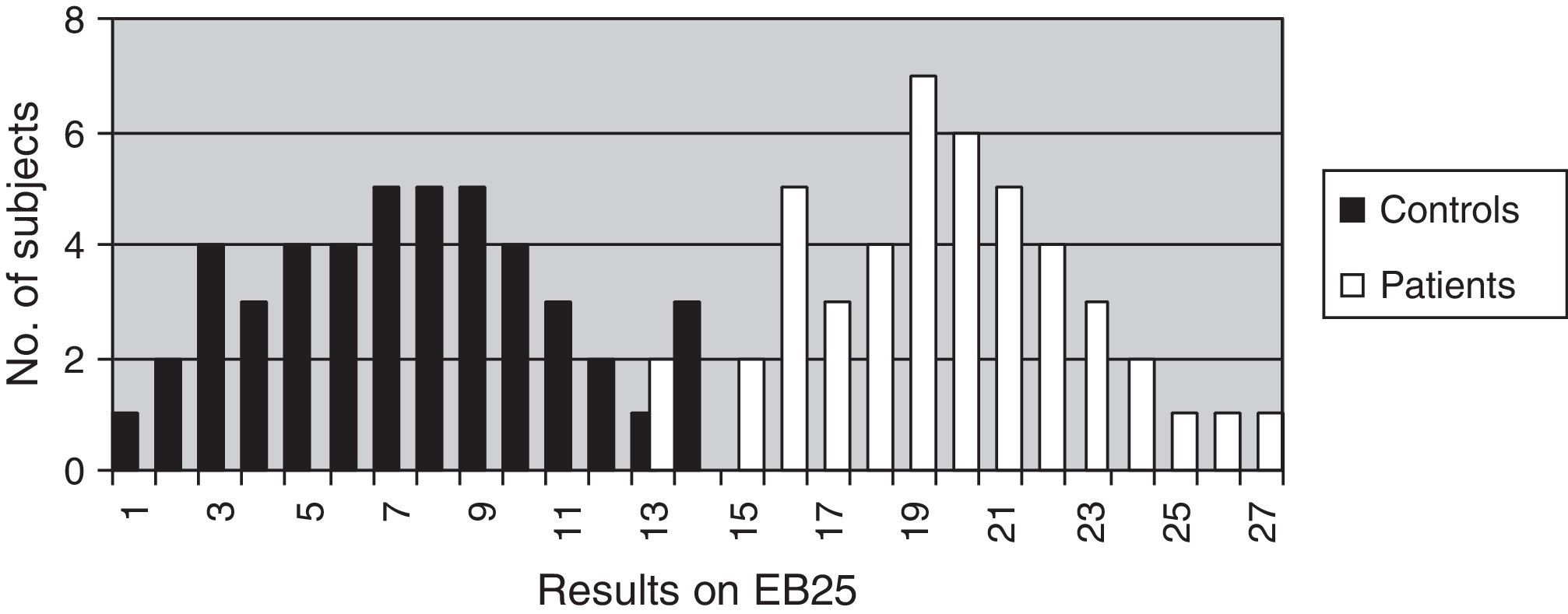

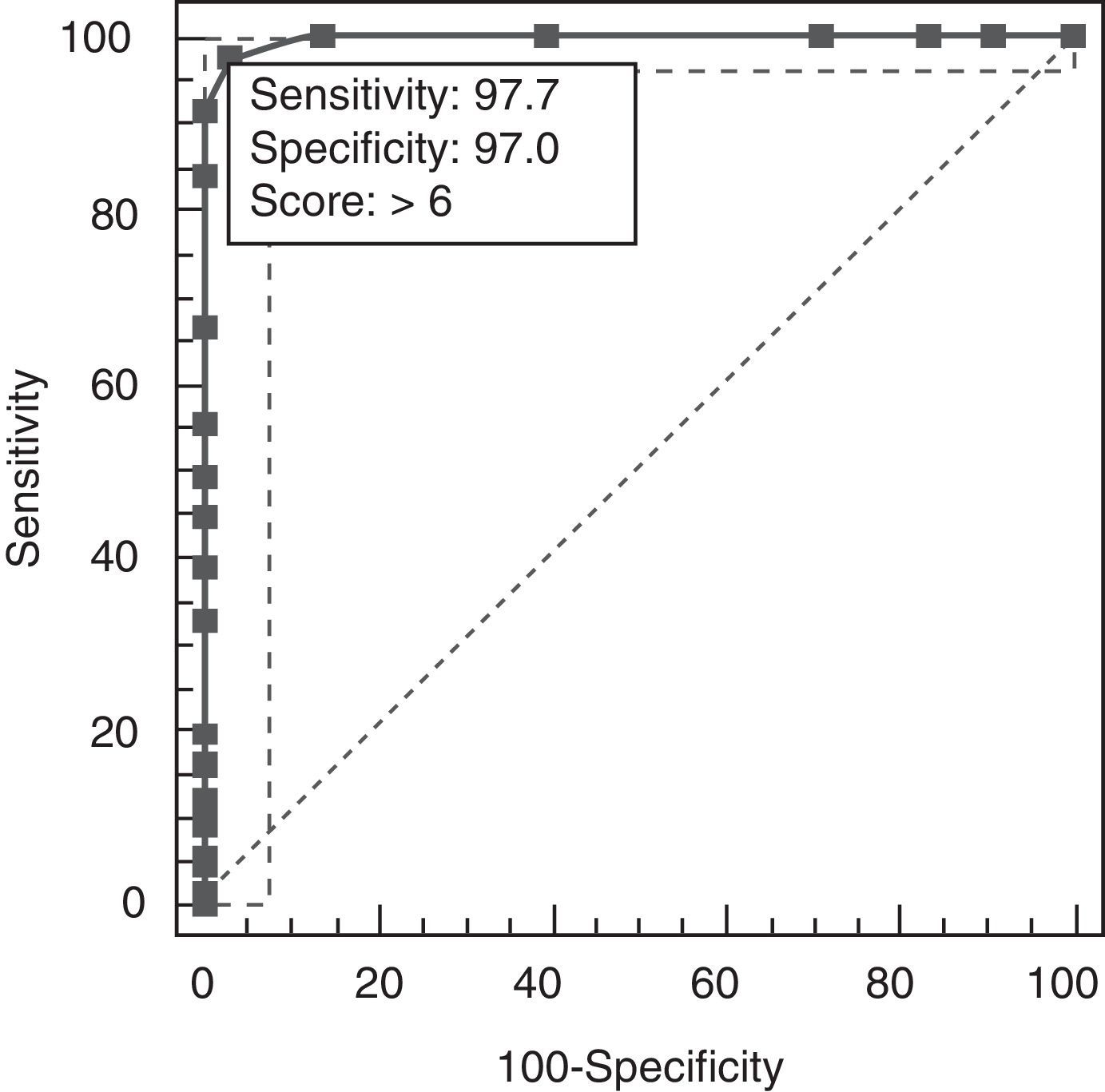

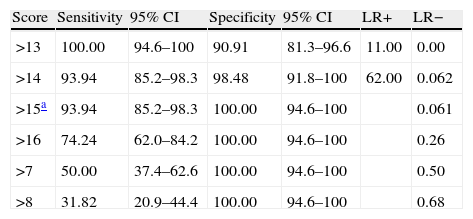

The discriminant validity between patients and controls was established using a ROC curve. Area under the curve (AUC) was 0.997 (95% CI, 0.966–1.000; P<.0001 for a cut-off point of 15). Specificity and sensitivity values for adjacent cut-off points are shown in Table 6. Fig. 1 shows discriminant results from EB25 for the 2 groups, and Table 6 shows values for adjacent cut-off points. Healthy controls have scores within the normal range (<15), while patients with dementia show disparate results. Some of the patients had scores below 15, overlapping with the control group, while the rest had scores well over the cut-off point (Fig. 2).

Specificity and sensitivity values for EB25 cut-off points.

| Score | Sensitivity | 95% CI | Specificity | 95% CI | LR+ | LR− |

| >13 | 100.00 | 94.6–100 | 90.91 | 81.3–96.6 | 11.00 | 0.00 |

| >14 | 93.94 | 85.2–98.3 | 98.48 | 91.8–100 | 62.00 | 0.062 |

| >15a | 93.94 | 85.2–98.3 | 100.00 | 94.6–100 | 0.061 | |

| >16 | 74.24 | 62.0–84.2 | 100.00 | 94.6–100 | 0.26 | |

| >7 | 50.00 | 37.4–62.6 | 100.00 | 94.6–100 | 0.50 | |

| >8 | 31.82 | 20.9–44.4 | 100.00 | 94.6–100 | 0.68 |

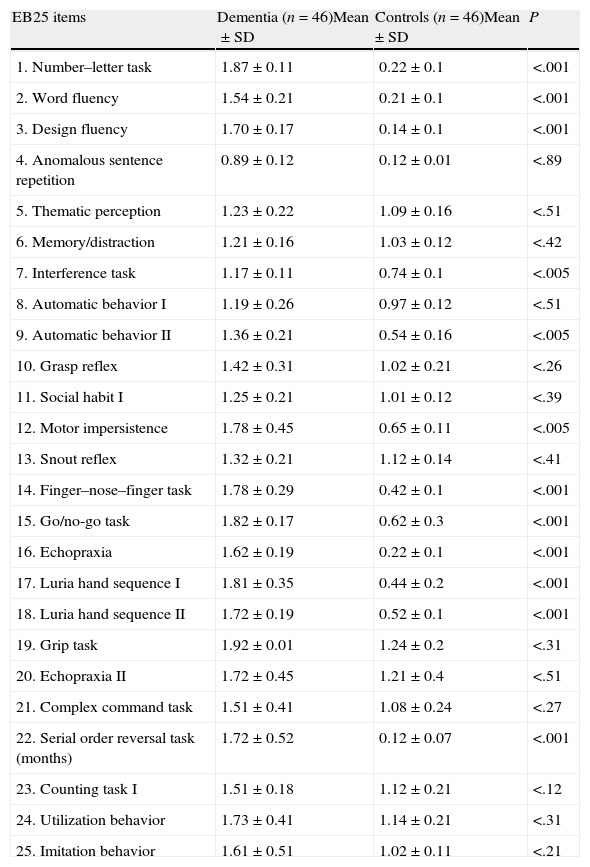

There were statistically significant differences between patients and controls on 12 items, allowing us to distinguish between groups (Table 7).

Level of statistical significance determined by comparing performance on each EB25 item between patients and controls.

| EB25 items | Dementia (n=46)Mean±SD | Controls (n=46)Mean±SD | P |

| 1. Number–letter task | 1.87±0.11 | 0.22±0.1 | <.001 |

| 2. Word fluency | 1.54±0.21 | 0.21±0.1 | <.001 |

| 3. Design fluency | 1.70±0.17 | 0.14±0.1 | <.001 |

| 4. Anomalous sentence repetition | 0.89±0.12 | 0.12±0.01 | <.89 |

| 5. Thematic perception | 1.23±0.22 | 1.09±0.16 | <.51 |

| 6. Memory/distraction | 1.21±0.16 | 1.03±0.12 | <.42 |

| 7. Interference task | 1.17±0.11 | 0.74±0.1 | <.005 |

| 8. Automatic behavior I | 1.19±0.26 | 0.97±0.12 | <.51 |

| 9. Automatic behavior II | 1.36±0.21 | 0.54±0.16 | <.005 |

| 10. Grasp reflex | 1.42±0.31 | 1.02±0.21 | <.26 |

| 11. Social habit I | 1.25±0.21 | 1.01±0.12 | <.39 |

| 12. Motor impersistence | 1.78±0.45 | 0.65±0.11 | <.005 |

| 13. Snout reflex | 1.32±0.21 | 1.12±0.14 | <.41 |

| 14. Finger–nose–finger task | 1.78±0.29 | 0.42±0.1 | <.001 |

| 15. Go/no-go task | 1.82±0.17 | 0.62±0.3 | <.001 |

| 16. Echopraxia | 1.62±0.19 | 0.22±0.1 | <.001 |

| 17. Luria hand sequence I | 1.81±0.35 | 0.44±0.2 | <.001 |

| 18. Luria hand sequence II | 1.72±0.19 | 0.52±0.1 | <.001 |

| 19. Grip task | 1.92±0.01 | 1.24±0.2 | <.31 |

| 20. Echopraxia II | 1.72±0.45 | 1.21±0.4 | <.51 |

| 21. Complex command task | 1.51±0.41 | 1.08±0.24 | <.27 |

| 22. Serial order reversal task (months) | 1.72±0.52 | 0.12±0.07 | <.001 |

| 23. Counting task I | 1.51±0.18 | 1.12±0.21 | <.12 |

| 24. Utilization behavior | 1.73±0.41 | 1.14±0.21 | <.31 |

| 25. Imitation behavior | 1.61±0.51 | 1.02±0.11 | <.21 |

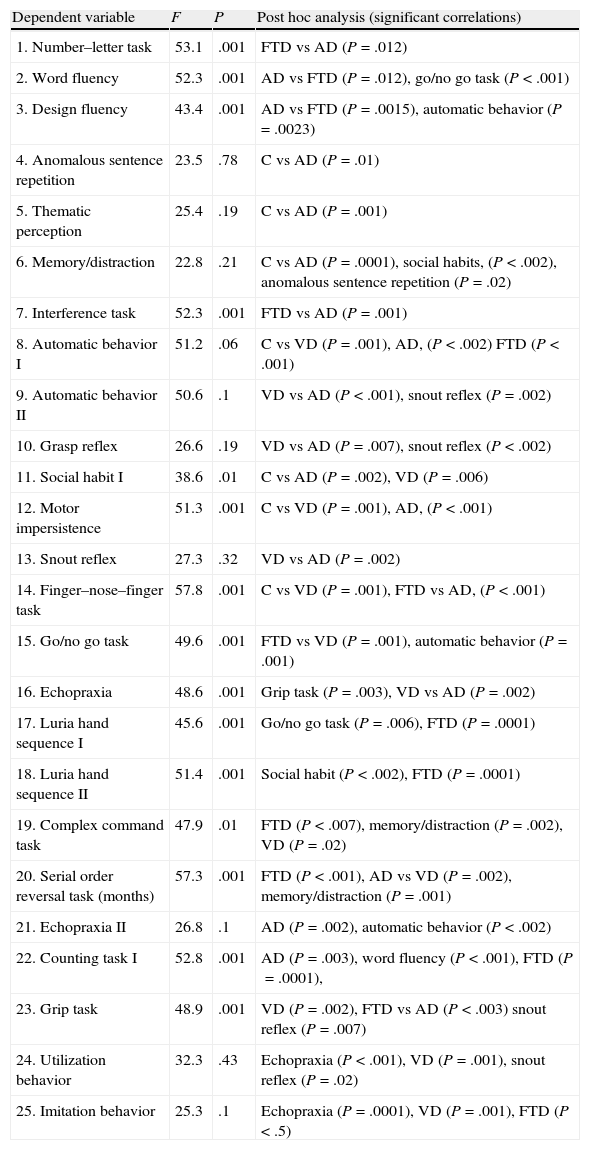

A backward stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis provided the results listed below. (1) Number–letter task (P=.046; OR=0.18, 95% CI, 0.32–0.96); (2) word fluency (P=.034; OR=0.21, 95% CI, 0.05–0.89); (3) design fluency (P=.036; OR=0.18; 95% CI, 0.22–0.66); (4) automatic behavior (P=.041; OR=0.12, 95% CI, 0.39–0.68); (5) interference task (P=.02; OR=0.06, 95% CI, 0.01–0.16); (6) motor impersistence (P=.033, OR=0.15, 95% CI, 0.010–0.18); (7) finger–nose–finger task (P=.13, OR=0.05, 95% CI, 0.08–0.45), (8) go/no-go task (P=.25, OR=0.10, 95% CI, 0.10–0.88); (9) echopraxia I (P=.13, OR=0.02, 95% CI, 0.02–0.48); (10) Luria hand sequence I (P=.31, OR=0.5, 95% CI, 0.12–0.76), (11) Luria hand sequence II (P=.42, OR=0.21, 95% CI, 0.21–0.98), and (12) serial order reversal (P=.61, OR=0.09, 95% CI, 0.32–0.98). These results permitted independent discrimination between control, AD, and FTD groups with a significant inter-subject effect (P=.001) for FTD and AD (Table 8).

ANCOVA between FTD, AD, and controls, with age, years of education, and CDR score as covariables; post hoc analysis of significant correlations.

| Dependent variable | F | P | Post hoc analysis (significant correlations) |

| 1. Number–letter task | 53.1 | .001 | FTD vs AD (P=.012) |

| 2. Word fluency | 52.3 | .001 | AD vs FTD (P=.012), go/no go task (P<.001) |

| 3. Design fluency | 43.4 | .001 | AD vs FTD (P=.0015), automatic behavior (P=.0023) |

| 4. Anomalous sentence repetition | 23.5 | .78 | C vs AD (P=.01) |

| 5. Thematic perception | 25.4 | .19 | C vs AD (P=.001) |

| 6. Memory/distraction | 22.8 | .21 | C vs AD (P=.0001), social habits, (P<.002), anomalous sentence repetition (P=.02) |

| 7. Interference task | 52.3 | .001 | FTD vs AD (P=.001) |

| 8. Automatic behavior I | 51.2 | .06 | C vs VD (P=.001), AD, (P<.002) FTD (P<.001) |

| 9. Automatic behavior II | 50.6 | .1 | VD vs AD (P<.001), snout reflex (P=.002) |

| 10. Grasp reflex | 26.6 | .19 | VD vs AD (P=.007), snout reflex (P<.002) |

| 11. Social habit I | 38.6 | .01 | C vs AD (P=.002), VD (P=.006) |

| 12. Motor impersistence | 51.3 | .001 | C vs VD (P=.001), AD, (P<.001) |

| 13. Snout reflex | 27.3 | .32 | VD vs AD (P=.002) |

| 14. Finger–nose–finger task | 57.8 | .001 | C vs VD (P=.001), FTD vs AD, (P<.001) |

| 15. Go/no go task | 49.6 | .001 | FTD vs VD (P=.001), automatic behavior (P=.001) |

| 16. Echopraxia | 48.6 | .001 | Grip task (P=.003), VD vs AD (P=.002) |

| 17. Luria hand sequence I | 45.6 | .001 | Go/no go task (P=.006), FTD (P=.0001) |

| 18. Luria hand sequence II | 51.4 | .001 | Social habit (P<.002), FTD (P=.0001) |

| 19. Complex command task | 47.9 | .01 | FTD (P<.007), memory/distraction (P=.002), VD (P=.02) |

| 20. Serial order reversal task (months) | 57.3 | .001 | FTD (P<.001), AD vs VD (P=.002), memory/distraction (P=.001) |

| 21. Echopraxia II | 26.8 | .1 | AD (P=.002), automatic behavior (P<.002) |

| 22. Counting task I | 52.8 | .001 | AD (P=.003), word fluency (P<.001), FTD (P=.0001), |

| 23. Grip task | 48.9 | .001 | VD (P=.002), FTD vs AD (P<.003) snout reflex (P=.007) |

| 24. Utilization behavior | 32.3 | .43 | Echopraxia (P<.001), VD (P=.001), snout reflex (P=.02) |

| 25. Imitation behavior | 25.3 | .1 | Echopraxia (P=.0001), VD (P=.001), FTD (P<.5) |

C, controls; AD, Alzheimer disease; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; VD, vascular dementia.

The numbers indicate item order within the EB25 interview.

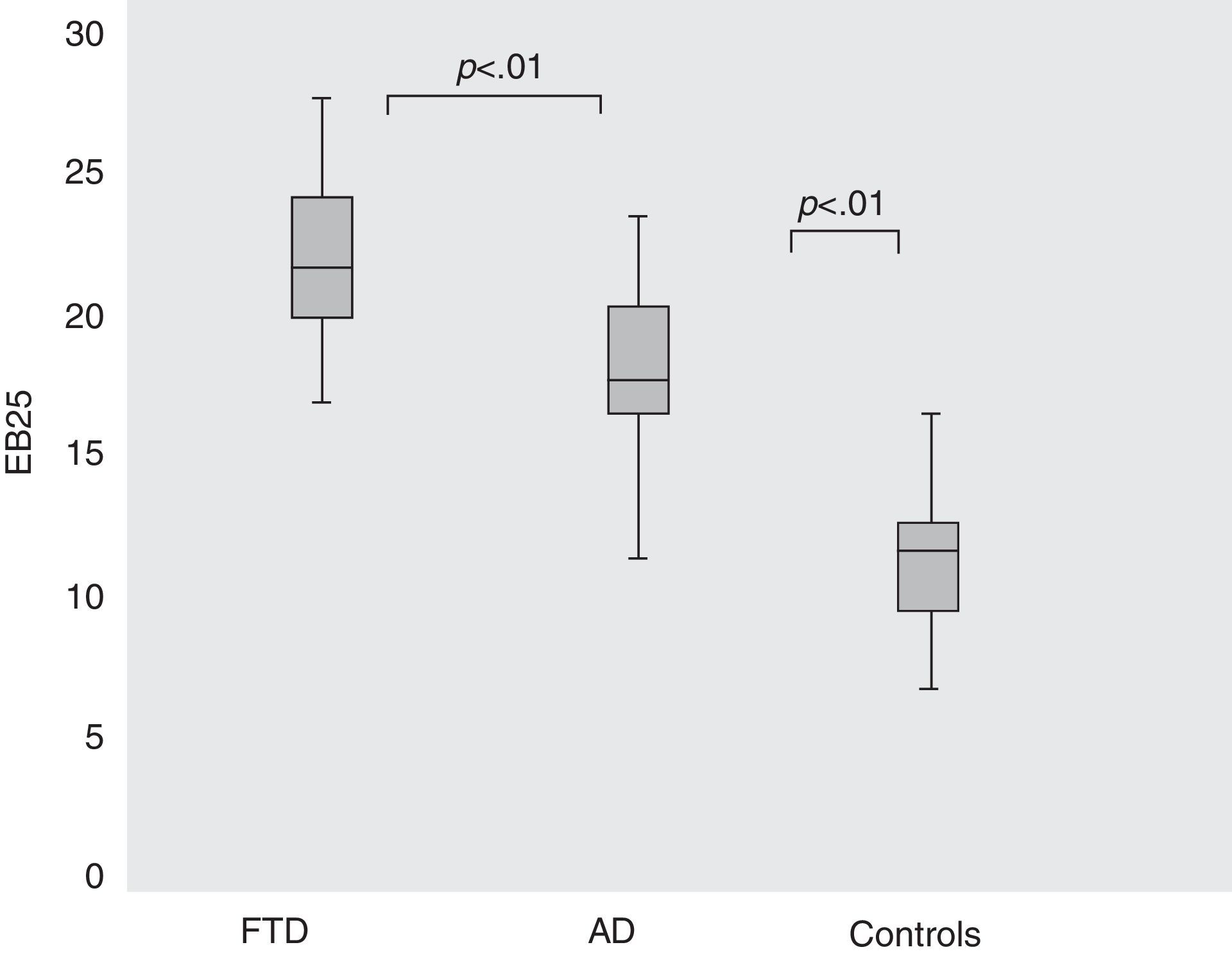

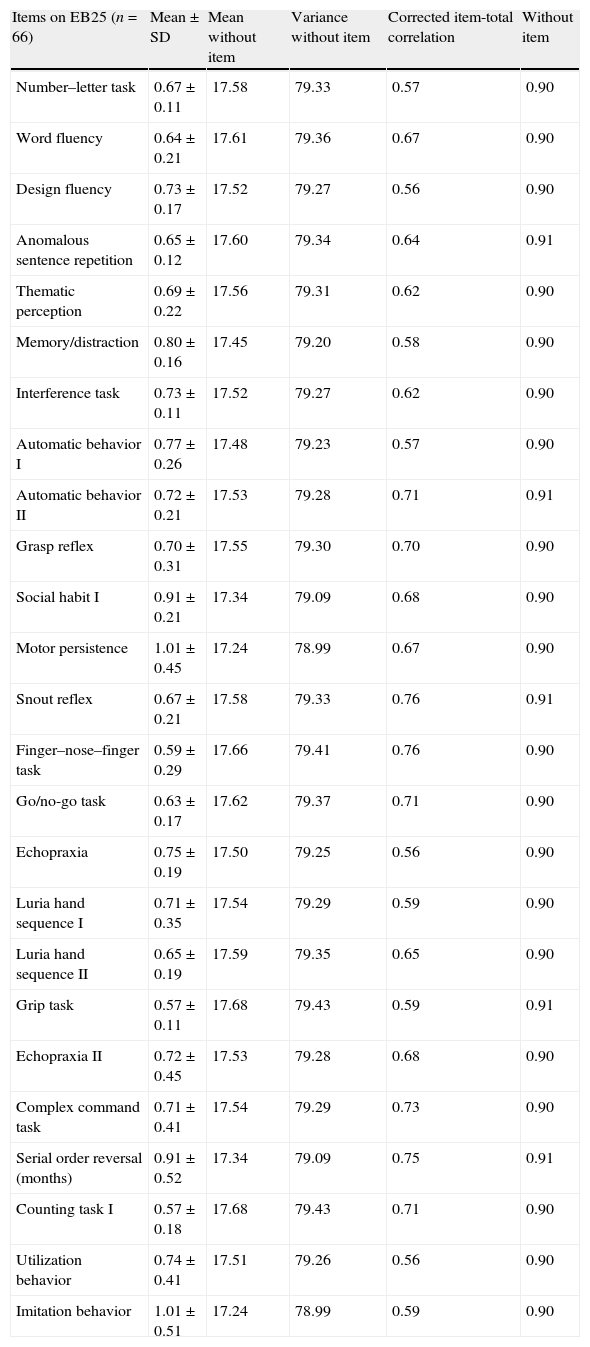

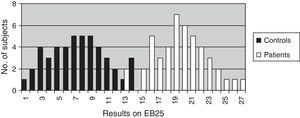

These two subgroups showed different total scores on the EB25; for AD, 18.34 (SD=2.7), for FTD 22.45 (SD=2.4), and for controls, 13.26 (SD=1.74). ANOVA and the Kruskal–Wallis test found that the difference was significant (F3,131=58.33; P<.001) (Fig. 3).

Results from EB25 in controls and in patients with AD or FTD. Comparison of total EB25 results for control, AD, and TFD groups (ANOVA [F3,131]=58.33; P<.001). Boxes indicate means (central line), the 25th percentile (the lower edge of the box) and the 75th percentile (the upper edge of the box). Bars show the 10th percentile (lowest mark) and the 90th percentile (highest mark) for each group. FTD, frontotemporal dementia; AD, Alzheimer disease.

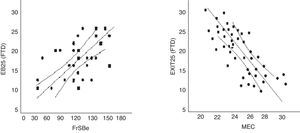

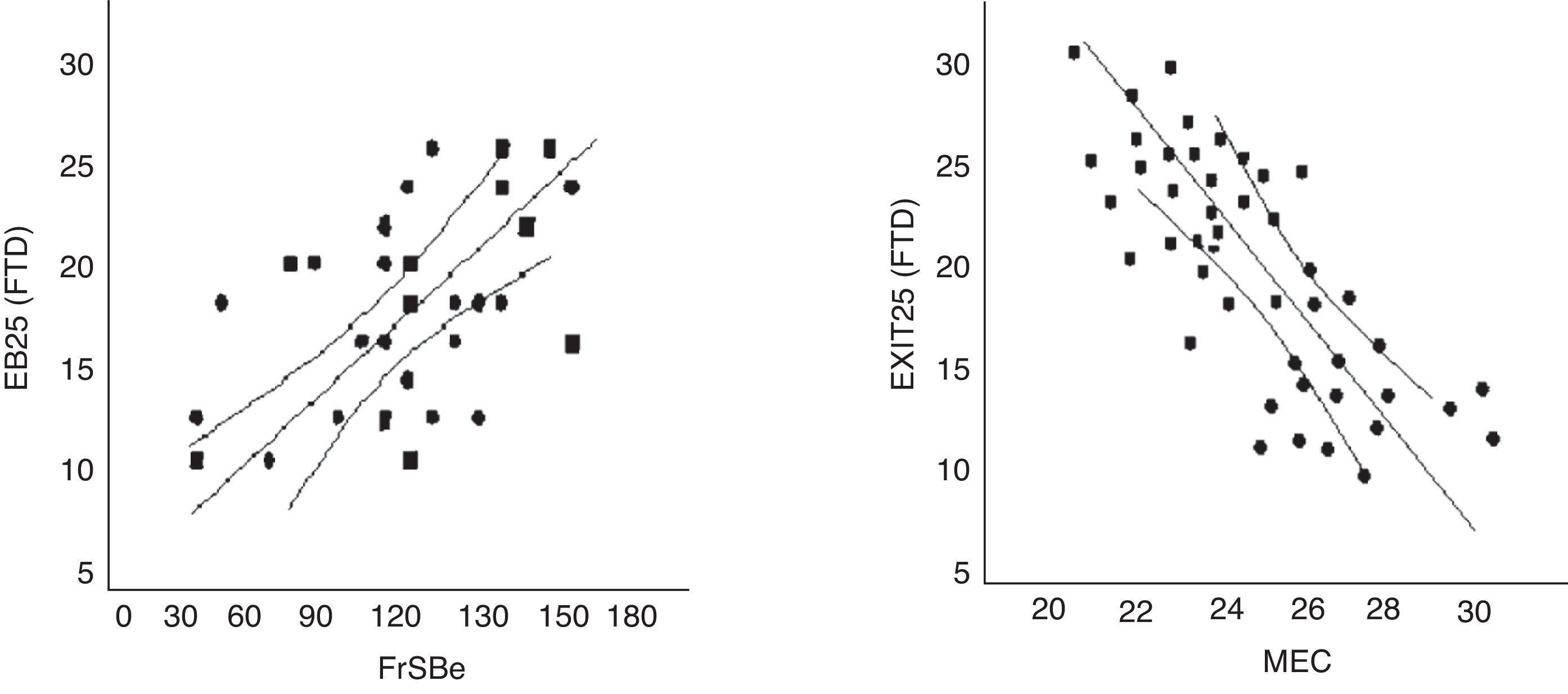

EB25 scores in the FTD population were strongly correlated to scores from FrSBe (r=0.56; P<.01), TMT-B (r=0.61; P<.01), WCST (r=0.64; P<.01), word fluency (r=0.67; P<.01), and categorical fluency (r=0.63; P<.01). There was no strong correlation with MEC (r=0.32; P=.67) (Fig. 4).

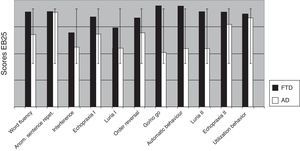

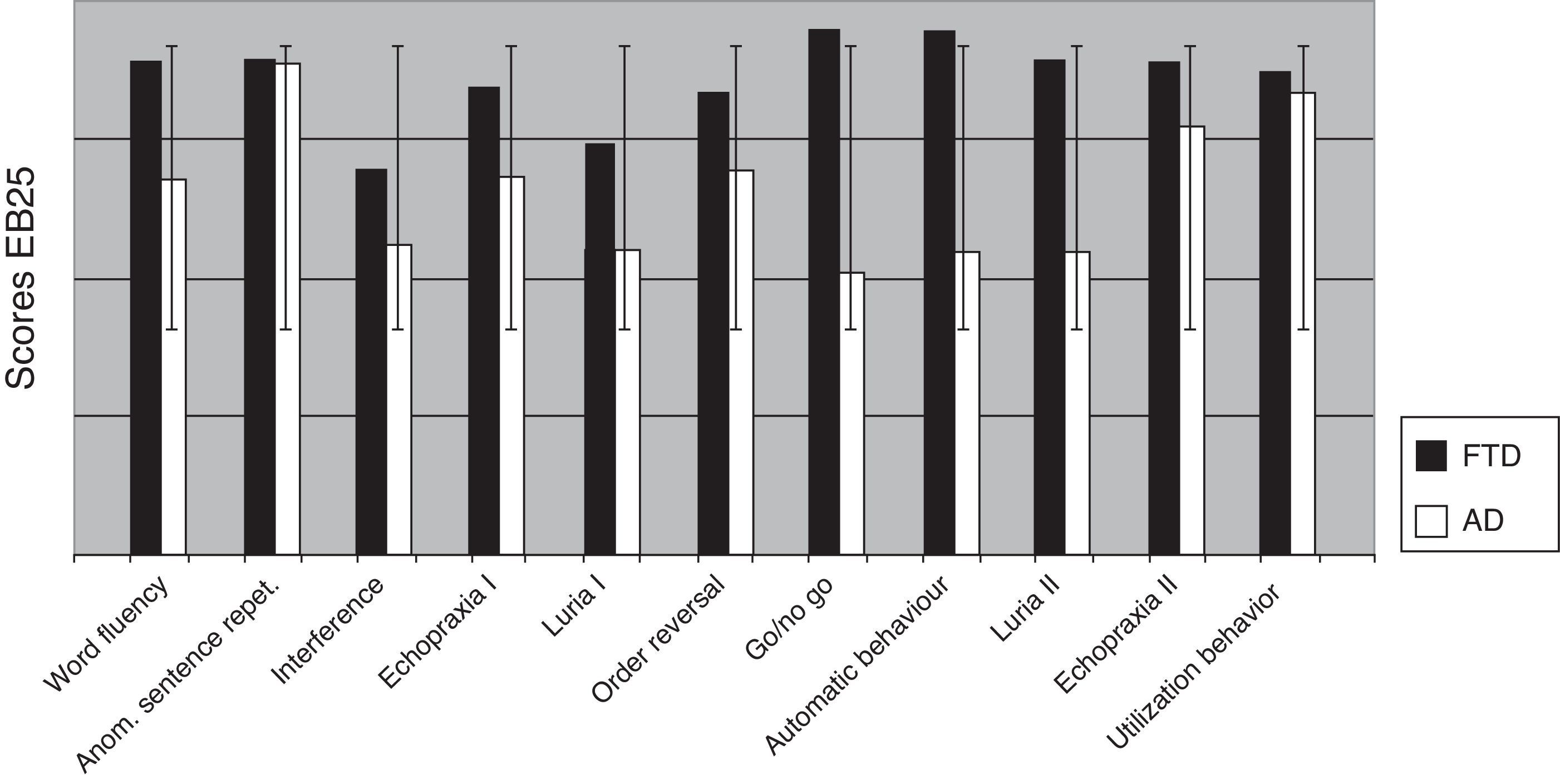

Comparing AD and FTD patients for each of the 25 items in EB25 revealed significant differences on the go/no go task (P=.008), word fluency (P<.004), automatic behavior (P<.001), and Luria hand sequence II (P=.001) (Fig. 5).

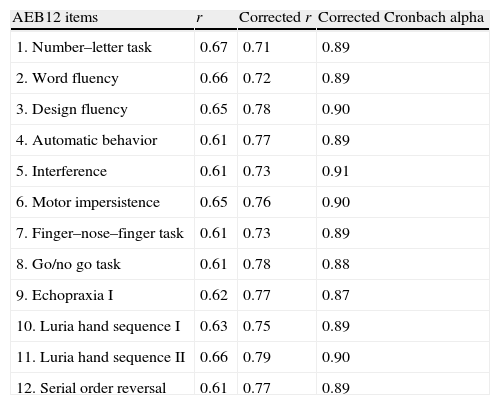

Based on the above data, we selected the most useful items for distinguishing controls from AD or FTD patients and created an abbreviated version of EB25 (AEB12, Appendix B). One of the psychiatrists administered this abbreviated version to patients and controls in 2 visits scheduled a week apart. A second psychiatrist administered the test a third time to check for inter-evaluator reliability. The Cronbach alpha for AEB12 was 0.92, with a mean item-total correlation of 0.61 (SD=0.001 (Table 9).

Item-total correlation test with corrected Cronbach alpha.

| AEB12 items | r | Corrected r | Corrected Cronbach alpha |

| 1. Number–letter task | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.89 |

| 2. Word fluency | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.89 |

| 3. Design fluency | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.90 |

| 4. Automatic behavior | 0.61 | 0.77 | 0.89 |

| 5. Interference | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.91 |

| 6. Motor impersistence | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.90 |

| 7. Finger–nose–finger task | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.89 |

| 8. Go/no go task | 0.61 | 0.78 | 0.88 |

| 9. Echopraxia I | 0.62 | 0.77 | 0.87 |

| 10. Luria hand sequence I | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.89 |

| 11. Luria hand sequence II | 0.66 | 0.79 | 0.90 |

| 12. Serial order reversal | 0.61 | 0.77 | 0.89 |

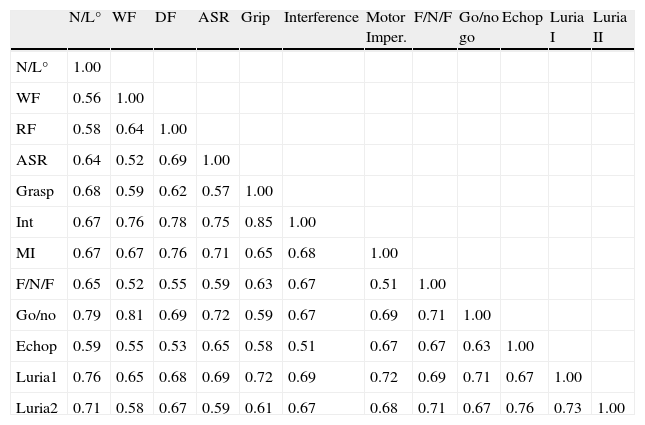

A split-half reliability test for the scale with items randomly assigned to one half or the other yielded a Cronbach alpha of 0.89 for the first half and 0.93 for the second half, with a Spearman–Brown correlation of 0.91. Correlation between items on the abbreviated test is shown in Table 10.

Correlations between AEB12 items.

| N/L° | WF | DF | ASR | Grip | Interference | Motor Imper. | F/N/F | Go/no go | Echop | Luria I | Luria II | |

| N/L° | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| WF | 0.56 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| RF | 0.58 | 0.64 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| ASR | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.69 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Grasp | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Int | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 1.00 | ||||||

| MI | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 1.00 | |||||

| F/N/F | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 1.00 | ||||

| Go/no | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 1.00 | |||

| Echop | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 1.00 | ||

| Luria1 | 0.76 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 1.00 | |

| Luria2 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 1.00 |

F/N/F, finger–nose–finger task; Echop, echopraxia; DF, design fluency; WF, word fluency; Go/no, Go/no go task; MI, motor impersistence; Int, interference; N/L, number-letter task; Luria1, Luria hand sequence I; Luria2, Luria hand sequence II; ASR, anomalous sentence repetition; Grasp, grasp reflex.

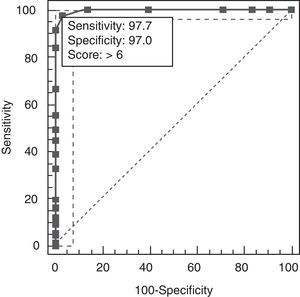

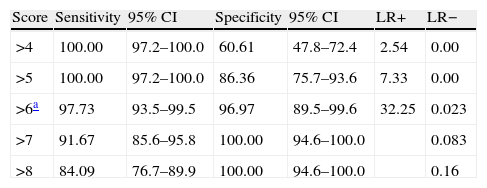

Results revealed a good test–retest correlation (ICC=0.89, 95% CI, 0.76–0.94) and inter-evaluator correlation (ICC=0.94, 95% CI, 0.86–0.99). The total result on AEB12 was 4.32±1.2 for controls, 9.65±1.34 for AD, and 15.21±1.16 for FTD. Concurrent validity was demonstrated by results from FrSBe (r=0.92; 95% CI, 0.82–0.98), TMT-B (r=0.86; 95% CI, 0.82–0.90), Stroop test (r=0.85; 95% CI, 0.81–0.88), WCST (r=0.84; 95% CI, 0.79–0.89), categorical fluency (r=0.81; 95% CI, 0.77–0.91), lexical fluency (r=0.82; 95% CI, 0.75–0.88), similarities (r=0.82; 95% CI, 0.73–0.86), RDRS-2 (r=0.85; 95% CI, 0.80–0.89), MEC (r=0.35; 95% CI, 0.30–0.45), and BPRS (r=0.91; 95% CI, 0.84–0.96). Divergent validity with NEUROPSI was robust (r=−0.47; 95% CI, 0.43–0.61). Multivariate analysis showed that the total result of AEB12 permitted differentiation between controls and FTD/AD patients independently (P=.001; OR=0.79, 95% CI, 0.70–0.89). Construct validity was tested by analysing principal components using Oblimin rotation of the 12 items on the AEB12 interview. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.89, and results from the Bartlett test of sphericity were significant (χ2=197.53; P<.001). The analysis revealed a single factor that explained 63.04% of the variance. We plotted ROC curves of AEB12 results to select the optimum cut-off point for detecting executive dysfunction in our patient samples. This allowed us to determine the test's discriminant validity for patients and controls and for AD and FTD populations. A cut-off point of 6 was used to differentiate between patients and controls (Fig. 6).

The AUC was 0.997 (95% CI, 0.976–1.000, P<.0001). Sensitivity and specificity values for adjacent cut-off points are shown in Table 11.

Sensitivity and specificity for the AEB12 cut-off point.

| Score | Sensitivity | 95% CI | Specificity | 95% CI | LR+ | LR− |

| >4 | 100.00 | 97.2–100.0 | 60.61 | 47.8–72.4 | 2.54 | 0.00 |

| >5 | 100.00 | 97.2–100.0 | 86.36 | 75.7–93.6 | 7.33 | 0.00 |

| >6a | 97.73 | 93.5–99.5 | 96.97 | 89.5–99.6 | 32.25 | 0.023 |

| >7 | 91.67 | 85.6–95.8 | 100.00 | 94.6–100.0 | 0.083 | |

| >8 | 84.09 | 76.7–89.9 | 100.00 | 94.6–100.0 | 0.16 |

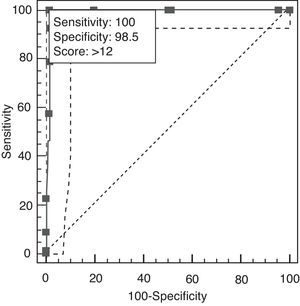

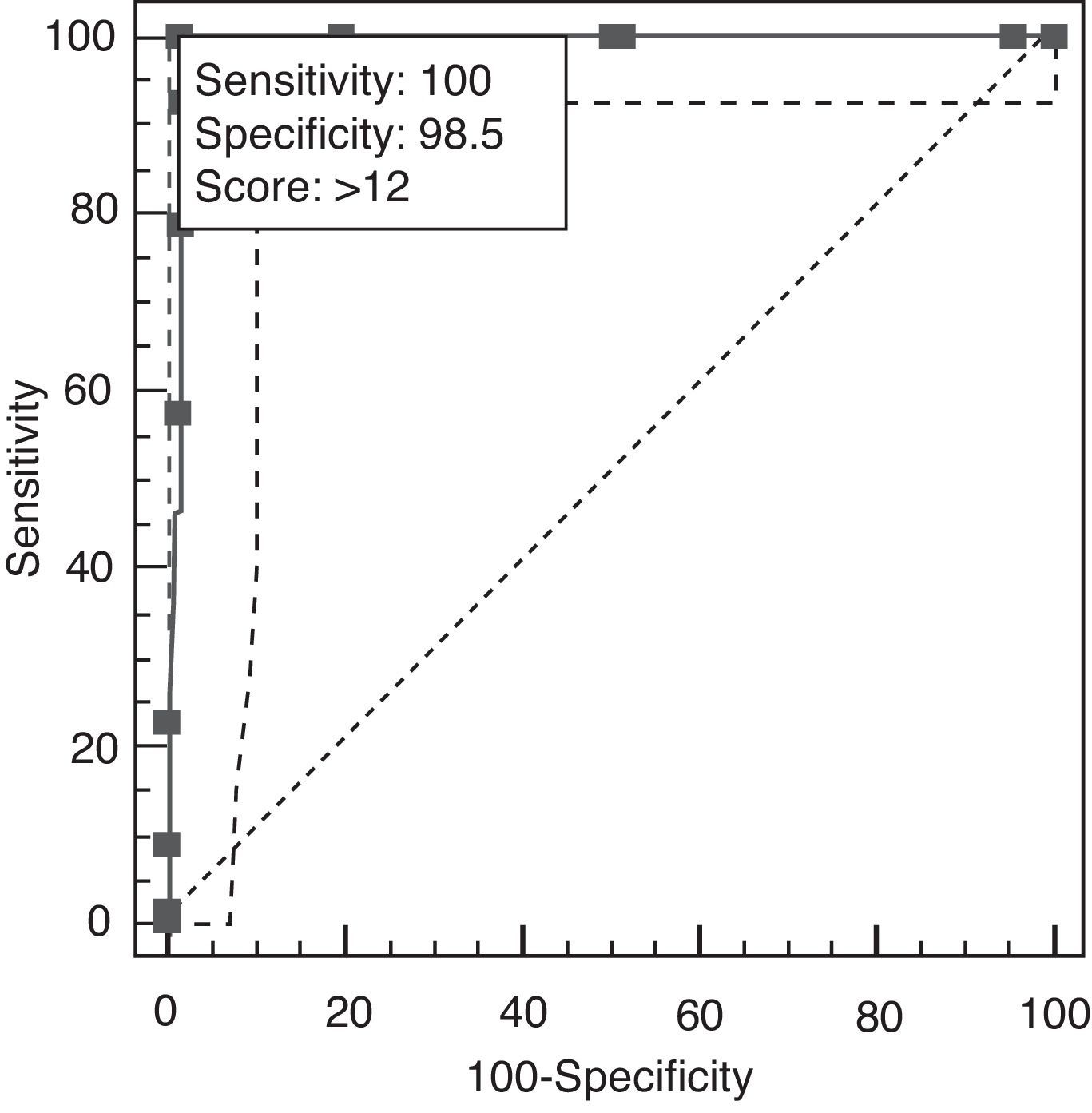

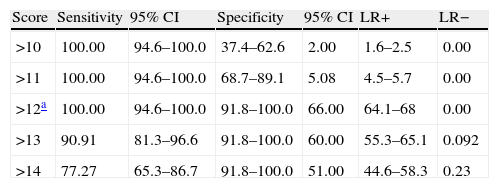

A cut-off point of 12 lets us distinguish between AD and TFD on the AEB12; AUC is 0.991 (95% CI, 0.956–1.000; P<.0001 (Fig. 7). Sensitivity and specificity values for adjacent cut-off points are shown in Table 12. Administration times for the EB25 and its abbreviated 12-item version are shown in Table 13.

Sensitivity and specificity values for adjacent cut-off points that distinguish between AD and FTD.

| Score | Sensitivity | 95% CI | Specificity | 95% CI | LR+ | LR− |

| >10 | 100.00 | 94.6–100.0 | 37.4–62.6 | 2.00 | 1.6–2.5 | 0.00 |

| >11 | 100.00 | 94.6–100.0 | 68.7–89.1 | 5.08 | 4.5–5.7 | 0.00 |

| >12a | 100.00 | 94.6–100.0 | 91.8–100.0 | 66.00 | 64.1–68 | 0.00 |

| >13 | 90.91 | 81.3–96.6 | 91.8–100.0 | 60.00 | 55.3–65.1 | 0.092 |

| >14 | 77.27 | 65.3–86.7 | 91.8–100.0 | 51.00 | 44.6–58.3 | 0.23 |

The purpose of this study is to provide and validate EB25, a Spanish translation of the EXIT 25 interview measuring executive dysfunction in patients with mild dementia (CDR 1). Results from patients with dementia are compatible with executive dysfunction; these patients scored higher on EB25 than did normal controls matched by age, sex, and cognitive ability. In this study, EB25 demonstrated good results for psychometric properties, internal consistency, concurrent validity, and high levels of correlation to multiple executive function tests (word fluency, WCST categories and perseverative errors, TMT-B). It also showed an acceptable discriminant capacity, given that its accuracy for distinguishing between patients and controls was significant. The results from this sample showed a positive correlation between EB25 and the MEC, which indicates that the former may be useful for detecting cognitive decline. This is particularly true of cases of FTD that already show poor results on EB25 at a stage of disease at which MEC scores do not yet show abnormalities. However, the high scores on most EB25 tasks cannot be projected from MEC results only. This indicates that other areas are affected as well as overall cognitive ability. Different studies have found a close association between neuropsychological tasks (such as those in WCST,45 the Stroop test, and TMT-B46) and the function of the prefrontal cortex. This supports using these tests to measure executive function. Good levels of correlation between these tests and the EB25 show a robust association between total results and executive dysfunction measures in this patient group. On the other hand, the low level of correlation between NEUROPSI and EB25 domains suggest that the latter is specifically valid for executive dysfunction. We detected significant differences in the ability of certain items to independently discriminate between controls and patients. This was particularly noticeable for the go/no go task, Luria hand sequence tasks I and II, word and design fluency, interference, number–letter task, automatic behavior, motor impersistence, finger–nose–finger task, the echopraxia I task, and serial order reversal task. Since its item-total correlation was high, 12 items could be selected for use on an abbreviated interview. This version had similar psychometric properties to those of EB25, better internal consistency, and was also able to distinguish between controls and patients, and between AD and FTD subgroups. The FTD group had higher scores than subjects in the control or AD groups, indicating the most severe executive dysfunction (FTD, 15.21±1.16; control, 4.32±1.2; AD, 9.65±1.34; P<.0001). The go/no go task displayed some of the most pronounced effects in both patient groups. Impaired performance on this task indicates severe difficulty maintaining impulse control; this is not as noticeable for active imitation tasks (mimicking the evaluator's movements) as it is in inhibition tasks (not responding with one movement when the evaluator makes the movement twice). This response pattern has been described in patients with ventromedial frontal lobe lesions.47 Results from the Luria hand sequence tasks showed that patients had significant difficulty completing a sequence of movements, introducing changes and omissions in the sequence; other authors have already highlighted this phenomenon.48 These findings are consistent with early impairment of the predominantly frontal–orbital and dorsolateral substrate found in executive dysfunction.49 BE25 was significantly correlated to FrSBe, and especially to its executive dysfunction subscale (r=0.61; P<.01). Although cognitive impairment was in its early stages – all patients had mild dementia – behavioral symptoms were already noticeable enough to affect patients’ daily activities. The test's correlation to RDRS-2 was also significant, (r=0.59; P<.01), although lower than its correlation to MEC. One possible explanation is that the RDRS-2 is filled in by the patient's caregiver or family member who observes how the patient performs different tasks and is able to evaluate the level of assistance he/she needs with those tasks. Since this instrument assigns the same weight to very different situations (patients who are bedridden, on special diets, with poor sphincter control, or unable to walk), and these areas are not severely affected according to many caregivers or family members, the overall scores for these patients may be low. The resulting impression is that patients’ conditions are less severe than is really the case, which partially decreases the correlation between RDRS-2 and EB25 or AEB12. Inter-group analysis of each item on the EB25 revealed that 12 items are needed to differentiate between controls and dementia patients. The most valuable items are those measuring frontal lobe function (verbal and categorical fluency tests, go/no go tasks, conflicting instructions, and Luria hand sequences), which can detect frontal executive dysfunction in dementia patients. On the other hand, scores on the automatic behavior, grasp reflex, snout reflex, utilization behavior, and imitation tasks were low and did not differ significantly from scores in the control group. This may have occurred because patients had only mild dementia, and the behaviors examined in these sections become impaired in more advanced stages of dementia. Items measuring social behavior also showed normal results, except in the 36 cases of FTD, which has a greater impact on this dimension. Our study has several limitations. First, we found a significant difference between mean ages of patients with AD and with FTD, which may suggest that age has an effect on executive function. However, there were no significant differences in educational level between these groups, and education is the factor that might have the greatest effect on cognitive impairment. In addition, the items on EB25 and AEB12 showing the greatest effect in both groups were those specifically able to distinguish between FTD and AD, and no differences were observed. In contrast, there were differences for those tasks placing the largest cognitive burden on the memory or reasoning domains, as seen on the NEUROPSI or MEC tests, where groups had similar response patterns even though patients with FTD were younger; this is consistent with findings from other studies.50 Another of our study's limitations was its relatively small sample size. In the future, this study should be replicated with a larger sample and more types of dementia so as to be able to generalize findings. Since MEC and NEUROPSI are dementia screening tests intended for use in patients with cognitive changes, and they are particularly specific and sensitive for detecting Alzheimer disease but less sensitive for detecting executive dysfunction,51 they could be administered along with the AEB12 in order to detect dementia. Furthermore, although correlations were significant between the EB25/AEB12 and MEC in the patient sample, those correlations were not present when AD and FTD patient samples were compared separately. In this case, correlations between AEB12 and MEC were lower for the FTD group, which could indicate that AEB12 specifically detects certain deficits in executive function that are not discovered by other neurocognitive tests. In contrast, correlations for the AD patient group between AEB12 and MEC were present throughout the study. This phenomenon may be due to the following: a few general cognitive areas are necessary for the completion of tasks in the EB25 and AEB12. Dementia-induced impairment of these areas may result in poorer performance on the EB25 and AEB12 if domains including comprehension, language, and attention are not spared. The latter phenomenon was not observed in this study; this may have occurred because patients in the sample had only mild dementia (CDR 1). Although combining the AEB12 with another general cognitive test, such as the Lobo MEC, may seem like a reasonable approach to detecting executive dysfunctions in demanding environments, our study does not show that combination to be an effective means of detecting other types of dementia, such as AD or FTD. While the complexity of the executive functions means that it would be difficult for a single instrument to cover all aspects, our study indicates that EB25 and AEB12 are robust, brief, and easy-to-use instruments for use in evaluating executive functions in patients with AD or FTD.

ConclusionsEB25 demonstrated a general ability to evaluate executive function in patients with mild dementia, and its results are relatively independent from the overall cognitive level. Considering that many tests assessing frontal lobe impairment show few abnormalities in the early stages of dementia, EB25 is a useful complement to other global cognitive impairment tools as a means of detecting patients with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. This instrument showed good results for convergent and divergent validity, as well as test–retest and inter-evaluator reliability. Evidence for discriminant validity was confirmed based on the test's negative correlation with instruments measuring cognitive dimensions other than the executive functions. On the other hand, certain items could be eliminated without affecting either the internal global consistency or reliability. The resulting abbreviated executive interview, containing 12 items, was easier to administer. The abbreviated version demonstrated robust psychometric properties and showed itself highly reliable for distinguishing between control subjects and dementia patients with executive dysfunction.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare and have not received any private funding for this study.

1. TAREA LETRA-NÚMERO

Quisiera que repitiera algunos números y letras como en el siguiente ejemplo:

1-A, 2-B, 3… ¿Cuál es el siguiente? C.

Ahora inténtelo comenzado con el número 1. Continúe hasta que le diga basta.

RESULTADO:

0. Sin errores.

1. Completa la tarea con ayuda o repitiendo las instrucciones.

2. No completa la tarea.

2. FLUENCIA VERBAL

Le voy a nombrar una letra. La tarea que debe hacer es nombrar en un minuto tantas palabras como pueda que comiencen con esa letra.

Por ejemplo, con la letra A, se podría nombrar: ananá, animal, anzuelo, azulejo, azul, antiguo… etc. ¿Está listo/a? ¿Tiene alguna pregunta?

La letra es P, adelante.

RESULTADO:

0. 10 o más palabras.

1. 5 a 9 palabras.

2. Menos de 5 palabras.

3. FLUENCIA DE DIBUJO

Mire los siguientes dibujos. Cada uno está hecho con sólo 4 trazos. Le voy a dar un minuto para dibujar tantos dibujos DIFERENTES como pueda. La única regla es que cada uno debe ser diferente de los otros y ser dibujado con 4 líneas. Adelante.

RESULTADO:

0. 10 o más dibujos únicos (no copias de los ejemplos).

1. 5 a 9 dibujos únicos.

2. Menos de 5 dibujos únicos.

4. REPETICIÓN DE FRASES

Escuche con atención cada una de las siguientes oraciones y repítalas (leer con tono neutro).

Yo juro ser fiel a la bandera.

María alimentó a un pequeño cordero.

Una puntada a tiempo salva cientos de vidas.

Titila, titila pequeña estrellita.

a b c d e f g.

RESULTADO:

0. Sin errores.

1. Falla al hacer uno o más cambios.

3. Continúa con una o más expresiones (María tenía un pequeño cordero cuyo pelambre era tan suave como un algodón).

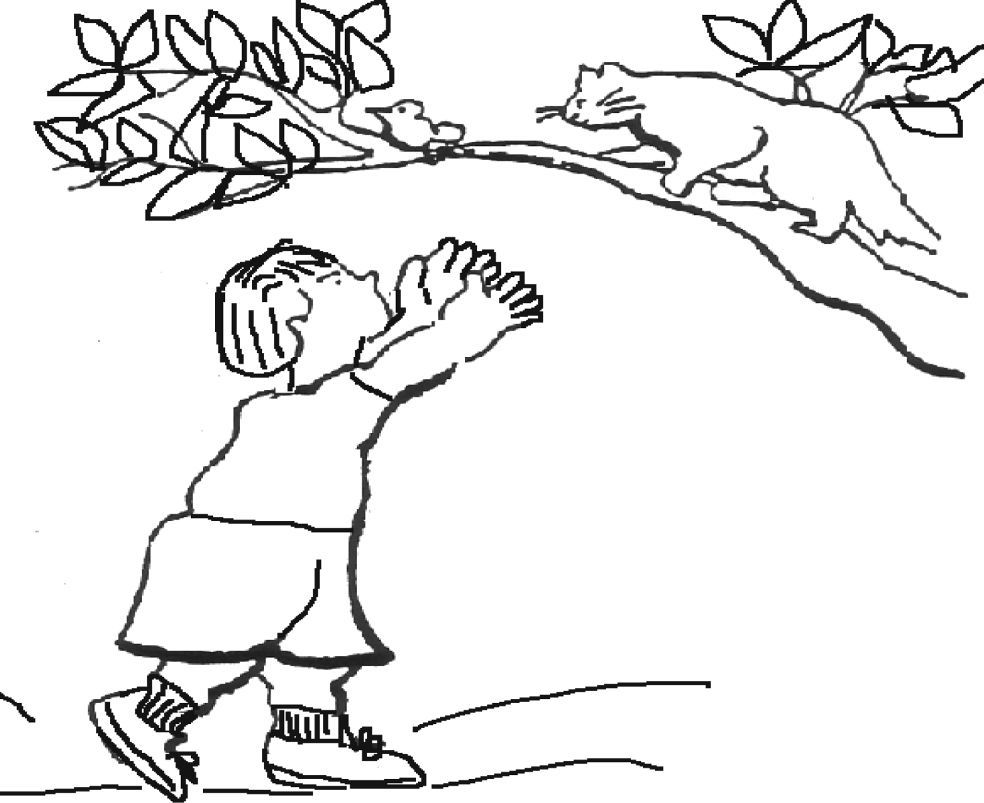

5. PERCEPCIÓN TEMÁTICA

Se le muestra al paciente la siguiente lámina y se le solicita que exprese lo que está ocurriendo en esa escena.

RESULTADO:

0. Narra espontáneamente una historia (historia=lugar, 3 personajes y la acción).

1. Narra una historia con ayuda x 1 («¿Algo más que agregar?»).

2. Falla al narrar una historia a pesar de la ayuda.

6. MEMORIA/DISTRACCIÓN

a. Se le solicita al paciente: «Trate de recordar estas tres palabras: libro, árbol, casa». A continuación, se le permite que repita las tres palabras hasta que las haya fijado.

b. Luego se le requiere: «Trate de recordarlas ya que le voy a pedir que las repita más adelante».

c. «Ahora, deletree la palabra paz (P-A-Z)».

d. A continuación se le dice: «Muy bien, ahora deletree la misma palabra hacia atrás (Z-A-P)».

e. «Ahora, repita las tres palabras que aprendió al comienzo».

RESULTADO:

0. El paciente repite algunas o las tres palabras correctamente sin nombrar la palabra paz (el entrevistador puede preguntar: «¿Algo más?»).

1. Otra respuesta. (Describir:____________).

2. El paciente nombra la palabra PAZ como una más de las tres palabras aprendidas (perseveración).

7. TAREA DE INTERFERENCIA

Se le muestra la siguiente palabra:

M A R R Ó N

A continuación se le pregunta: «¿De qué color son estas letras?».

(El entrevistador tapa y destapa las letras una por una sucesivamente).

RESULTADO:

0. «Negra».

1. «Marrón» (repetir la pregunta x 1), corrige diciendo «negro».

2. «Marrón» (repetir la pregunta x 1), no corrige y vuelve a repetir «marrón» (intrusión).

8. COMPORTAMIENTO AUTOMÁTICO I

a. El paciente sostiene sus manos extendidas hacia adelante con las palmas hacia abajo.

b. Se le dice: «Relájese mientras examino sus reflejos».

c. Se flexionan los brazos del paciente a la altura del codo, un brazo por vez, como si se estuviera examinando el signo del «caño de plomo». Medir la participación activa/anticipación del paciente con relación a la flexión del brazo.

RESULTADO:

0. El paciente permanece pasivo.

1. Movimientos dudosos, o intentos de flexión parciales sin completar el movimiento de flexión.

2. El paciente realiza activamente el movimiento de flexión anticipándose al examinador.

9. COMPORTAMIENTO AUTOMÁTICO II

a. El paciente sostiene sus manos extendidas hacia adelante con las palmas hacia arriba.

b. Se le dice: «Relájese mientras examino sus reflejos».

c. Se empujan las manos del paciente hacia abajo, al comienzo de manera suave, y luego aumentando la presión progresivamente. Medir la participación activa/anticipación del paciente con relación al descenso de la mano.

RESULTADO:

0. El paciente no ofrece resistencia (permanece pasivo).

1. Movimientos dudosos, o intentos de descenso parciales sin completar el movimiento de descenso.

2. El paciente resiste activamente (o colabora) con el entrevistador.

10. REFLEJO DE PRENSIÓN

a. El paciente sostiene las manos extendidas con las palmas hacia abajo.

b. Se le dice: «Relájese mientras examino sus reflejos».

c. Se estimulan ambas palmas simultáneamente con un toque suave, buscando despertar acciones de prensión/agarre en los dedos.

RESULTADO:

0. Ausente.

1. Movimientos dudosos, o intentos de flexión parciales de los dedos sin llegar a la prensión.

2. El paciente presenta prensión lo suficientemente firme como para ser levantado de la silla por el examinador.

11. HÁBITOS SOCIALES I

Fije la mirada del paciente. Cuente silenciosamente hasta tres mientras se mantiene la fijación de la Mirada, luego diga: «Gracias».

RESULTADO:

0. Responde con una pregunta (p. ej., «¿Gracias por qué?»).

1. Otra respuesta — (describa________).

2. Responde: «De nada».

12. PERSISTENCIA MOTORA

a.«Saque la lengua y diga: aah… hasta que le pida que se detenga».

b. «Comience» (cuente hasta tres en silencio).

c. El paciente debe mantener un tono constante, no «ah…, ah…, ah…».

RESULTADO:

0. Completa la tarea espontáneamente.

1. Completa la tarea si el examinador ejemplifica la tarea para el paciente.

2. Fracasa para completar la tarea a pesar de la ejemplificación de la tarea por el entrevistador.

13. REFLEJO DE HOCIQUEO

a. Se le dice: «Relájese mientras examino sus reflejos».

b. El examinador acerca su dedo índice hacia los labios del paciente, deteniéndose momentáneamente a una distancia de 1cm. Luego se coloca el dedo de manera vertical cruzando los labios y con la otra mano se lo golpea suavemente sobre los labios del paciente.

c. Observar la presencia de hociqueo.

RESULTADO:

0. Ausente.

1. Movimientos dudosos, o intentos de succión parciales de los labios sin llegar al hociqueo.

2. Presente.

14. TAREA DEDO-NARIZ

a. El entrevistador sostiene hacia adelante su dedo índice.

b. Le dice al paciente: «Toque mi dedo».

c. Dejando el dedo en el mismo lugar, le dice al paciente: «Ahora toque su nariz».

RESULTADO:

0. El paciente obedece, usando la misma mano.

1. Otra respuesta — describir _______

2. El paciente obedece, pero usando la otra mano, mientras continúa tocando el dedo del examinador.

15. TAREA GO-NO

a. Se le dice al paciente: «Cuando yo toque mi nariz, levante su dedo de esta manera» (el examinador levanta su dedo índice).

b. Se le dice al paciente: «Cuando levante mi dedo, usted tóquese la nariz de esta manera» (el examinador toca su nariz con su dedo índice).

c. Pedir al paciente que repita las instrucciones, si es posible, para asegurarse de que ha comprendido las consignas.

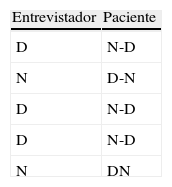

d. El entrevistador comienza la tarea. Deja los dedos en el lugar mientras espera la respuesta del paciente.

e. Examen del paciente según la siguiente secuencia:

RESULTADO:

0. El paciente sigue la secuencia correctamente.

1. Sigue la secuencia correctamente pero con ayuda/repitiendo las instrucciones.

2. Fracasa al seguir la secuencia a pesar de la ayuda/repetición de instrucciones.

16. ECOPRAXIA

a. Se le dice al paciente: «Ahora escuche con atención, debe hacer exactamente lo que le diga. «¿Está listo/a?».

b. «Toque su oreja». (El entrevistador toca su nariz y deja el dedo en ese lugar.)

RESULTADO:

0. El paciente toca su oreja.

1. Otra respuesta (fijarse si el paciente hace movimientos a «mitad de camino» o se detiene antes de completar el movimiento correcto).

2. El paciente toca su nariz.

17. SECUENCIA DE MANO DE LURIA I

a. Se le pide al paciente que observe mientras el examinador alterna movimientos de oposición palma/puño con ambas manos.

b. Véase la siguiente figura:

c. A continuación se le pregunta: «¿Puede hacer esto?».

d. Una vez que el paciente comienza a realizar el movimiento, instarlo a que continúe, al tiempo que el examinador detiene su propio movimiento.

e. Contar el número de ciclos correctos palma/puño.

SCORE:

0. 4 ciclos sin errores después que el entrevistador se detiene.

1. 4 ciclos con ayuda verbal («continúe realizando el movimiento») o con la ejemplificación.

2. Fracaso a pesar de ayuda verbal/ejemplificación (observar posiciones «a mitad de camino»).

18. SECUENCIA DE MANO DE LURIA II

a. Se le pide al paciente que observe mientras el examinador alterna movimientos de oposición palma/puño/canto con ambas manos.

b. Véase la siguiente figura:

c. A continuación se le pregunta: «¿Puede hacer esto?».

d. Mientras el examinador ejemplifica la secuencia de 3 movimientos, se le pide al paciente que lo imite repitiendo cada paso.

e. Una vez que el paciente comienza a realizar el movimiento, instarlo a que continúe, al tiempo que el examinador detiene su propio movimiento.

f. Contar el número de ciclos correctos palma/puño.

SCORE:

0. 3 ciclos sin errores después que el examinador interrumpe su propio movimiento.

1. 3 ciclos con ayuda verbal («continúe») o ejemplificación.

2. Fracaso a pesar de ayuda verbal/ejemplificación.

19. TAREA DE PRENSIÓN

a. El entrevistador le muestra sus manos al paciente.

b. Véase la siguiente figura:

c. A continuación, el entrevistador de pide al paciente: «Apriete mis dedos».

SCORE:

0. El paciente aprieta los dedos.

1. Otras respuestas — descríbalas _______

2. El paciente junta ambas manos del entrevistador.

20. ECOPRAXIA II

a. De manera brusca y sin previo aviso, el examinador junta sus manos, aplaudiendo una sola vez.

SCORE:

0. El paciente no imita al entrevistador.

1. El paciente duda, confundido.

2. El paciente imita el aplauso.

21. TAREA DE ÓRDENES COMPLEJAS

a. Coloque su mano izquierda encima de su cabeza y cierre los ojos.

b. El entrevistador le dice al paciente: «Eso estuvo bien» (El entrevistador permanece impávido y comienza la siguiente tarea.)

(IR RÁPIDAMENTE A LA SIGUIENTE TAREA).

SCORE:

0. El paciente se detiene cuando comienza la siguiente tarea.

1. Respuesta incierta –mantiene la postura durante parte de la siguiente tarea.

2. El paciente mantiene la postura mientras realiza la siguiente tarea —se le debe solicitar que deje la postura.

22. TAREA DE ORDENAMIENTO SERIAL INVERTIDO

a. Pedir al paciente que recite los meses del año.

b. Ahora, comience con enero y recite los meses del año hacia atrás.

SCORE:

0. Sin errores, al menos hasta pasar septiembre.

1. Pasa septiembre pero requiere la repetición de las instrucciones («simplemente comience en enero y repita los meses hacia atrás»).

2. Fracasa a pesar de la ayuda.

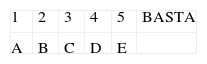

23. TAREA DE CONTAJE I

a. El entrevistador señala cada figura de la lámina siguiente, siguiendo la dirección de las agujas del reloj.

b. Se le solicita: «Por favor, cuente en voz alta los peces en la lámina».

SCORE:

0. Сuatro.

1. Menos de cuatro.

2. Más de cuatro.

24. COMPORTAMIENTO DE USO

a. El entrevistador sostiene una lapicera cerca de la punta y se la «presenta» bruscamente al paciente preguntando: «¿Cómo se llama esto?».

SCORE:

0. «Lapicera».

1. Duda, piensa, intenta coger la lapicera, responde con ayuda.

2. El paciente coge la lapicera del examinador (comportamiento de uso).

25. COMPORTAMIENTO DE IMITACIÓN

a. El entrevistador le muestra su muñeca al paciente, flexionándola hacia arriba y abajo, y le pregunta: «¿Cómo se llama esto?».

SCORE:

0. «Muñeca».

1. Otra respuesta (describirla:_______________).

2. El paciente flexiona su muñeca arriba y abajo (ecopraxia).

1. TAREA LETRA-NÚMERO

Quisiera que repitiera algunos números y letras como en el siguiente ejemplo:

1-A, 2-B, 3… ¿Cuál es el siguiente? C.

Ahora inténtelo comenzado con el número 1. Continúe hasta que le diga basta.

RESULTADO:

0. Sin errores.

1. Completa la tarea con ayuda o repitiendo las instrucciones.

2. No completa la tarea.

2. FLUENCIA VERBAL

Le voy a nombrar una letra. La tarea que debe hacer es nombrar en un minuto tantas palabras como pueda que comiencen con esa letra.

Por ejemplo, con la letra A, se podría nombrar: ananá, animal, anzuelo, azulejo, azul, antiguo… etc. ¿Está listo/a? ¿Tiene alguna pregunta?

La letra es P, adelante.

RESULTADO:

0. 10 o más palabras.

1. 5 a 9 palabras.

2. Menos de 5 palabras.

3. FLUENCIA DE DIBUJO

Mire los siguientes dibujos. Cada uno está hecho con sólo 4 trazos. Le voy a dar un minuto para dibujar tantos dibujos DIFERENTES como pueda. La única regla es que cada uno debe ser diferente de los otros y ser dibujado con 4 líneas. Adelante.

RESULTADO:

0. 10 o más dibujos únicos (no copias de los ejemplos).

1. 5 a 9 dibujos únicos.

2. Menos de 5 dibujos únicos.

4. TAREA DE INTERFERENCIA

Se le muestra la siguiente palabra:

M A R R Ó N

A continuación se le pregunta: «¿De qué color son estas letras?»

(el entrevistador tapa y destapa las letras una por una sucesivamente).

RESULTADO:

0. «Negra»

1. «Marrón» (repetir la pregunta x 1), corrige diciendo «negro».

2. «Marrón» (repetir la pregunta x 1), no corrige y vuelve a repetir «marrón» (intrusión)

5. COMPORTAMIENTO AUTOMÁTICO I

a. El paciente sostiene sus manos extendidas hacia adelante con las palmas hacia abajo.

b. Se le dice: «Relájese mientras examino sus reflejos».

c. Se flexionan los brazos del paciente a la altura del codo, un brazo por vez, como si se estuviera examinando el signo del «caño de plomo». Medir la participación activa/anticipación del paciente con relación a la flexión del bazo.

RESULTADO:

0. El paciente permanece pasivo.

1. Movimientos dudosos, o intentos de flexión parciales sin completar el movimiento de flexión.

2. El paciente realiza activamente el movimiento de flexión anticipándose al examinador.

6. IMPERSISTENCIA MOTORA

a. «Saque la lengua y diga: aah… hasta que le pida que se detenga».

b. «Comience» (cuente hasta tres en silencio).

c. El paciente debe mantener un tono constante, no «ah…, ah…, ah…».

RESULTADO:

0. Completa la tarea espontáneamente.

1. Completa la tarea si el examinador ejemplifica la tarea para el paciente.

2. Fracasa para completar la tarea a pesar de la ejemplificación de la tarea por el entrevistador.

7. TAREA DEDO-NARIZ

a. El entrevistador sostiene hacia adelante su dedo índice.

b. Le dice al paciente: «Toque mi dedo».

c. Dejando el dedo en el mismo lugar, le dice al paciente: «Ahora, toque su nariz».

RESULTADO:

0. El paciente obedece, usando la misma mano.

1. Otra respuesta — describir _______

2. El paciente obedece, pero usando la otra mano, mientras continúa tocando el dedo del examinador.

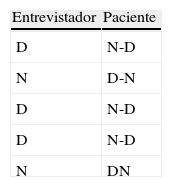

8. TAREA GO-NO

a. Se le dice al paciente: «Cuando yo toque mi nariz, levante su dedo de esta manera» (el examinador levanta su dedo índice).

b. Se le dice al paciente: «Cuando levante mi dedo, usted tóquese la nariz de esta manera» (el examinador toca su nariz con su dedo índice).

c. Pedir al paciente que repita las instrucciones, si es posible, para asegurarse de que ha comprendido las consignas

d. El entrevistador comienza la tarea. Deja los dedos en el lugar mientras espera la respuesta del paciente.

e. Examen del paciente según la siguiente secuencia:

RESULTADO:

0. El paciente sigue la secuencia correctamente.

1. Sigue la secuencia correctamente pero con ayuda/repitiendo las instrucciones.

2. Fracasa al seguir la secuencia a pesar de la ayuda/repetición de instrucciones.

9. ECOPRAXIA

a. Se le dice al paciente: «Ahora escuche con atención, debe hacer exactamente lo que le diga. ¿Está listo/a?».

b. «Toque su oreja» (el entrevistador toca su nariz y deja el dedo en ese lugar).

RESULTADO:

0. El paciente toca su oreja.

1. Otra respuesta (fijarse si el paciente hace movimientos a «mitad de camino» o se detiene antes de completar el movimiento correcto).

2. El paciente toca su nariz.

10. SECUENCIA DE MANO DE LURIA I

a. Se le pide al paciente que observe mientras el examinador alterna movimientos de oposición palma/puño con ambas manos.

b. Véase la siguiente figura:

c. A continuación se le pregunta: «¿Puede hacer esto?».

d. Una vez que el paciente comienza a realizar el movimiento, instarlo a que continúe, al tiempo que el examinador detiene su propio movimiento.

e. Contar el número de ciclos correctos palma/puño.

SCORE:

0. 4 ciclos sin errores después que el entrevistador se detiene.

1. 4 ciclos con ayuda verbal («continúe realizando el movimiento») o con la ejemplificación.

2. Fracaso a pesar de ayuda verbal/ejemplificación (observar posiciones «a mitad de camino»).

11. SECUENCIA DE MANO DE LURIA II

a. Se le pide al paciente que observe mientras el examinador alterna movimientos de oposición palma/puño/canto con ambas manos.

b. Véase la siguiente figura:

c. A continuación, se le pregunta: «¿Puede hacer esto?».

d. Mientras el examinador ejemplifica la secuencia de 3 movimientos, se le pide al paciente que lo imite repitiendo cada paso.

e. Una vez que el paciente comienza a realizar el movimiento, instarlo a que continúe, al tiempo que el examinador detiene su propio movimiento.

f. Contar el número de ciclos correctos palma/puño.

SCORE:

0. 3 ciclos sin errores después que el examinador interrumpe su propio movimiento.

1. 3 ciclos con ayuda verbal («continúe») o ejemplificación.

2. fracaso a pesar de ayuda verbal/ejemplificación.

12. TAREA DE ORDENAMIENTO SERIAL INVERTIDO

a. Pedir al paciente que recite los meses del año.

b. Ahora, comience con enero y recite los meses del año hacia atrás.

SCORE:

0. Sin errores, al menos hasta pasar septiembre.

1. Pasa septiembre pero requiere la repetición de las instrucciones («simplemente comience en enero y repita los meses hacia atrás»).

2. Fracasa a pesar de la ayuda.

Please cite this article as: Serrani Azcurra DJL. Traducción al español y validación de una batería ejecutiva (BE25) y su versión abreviada (ABE12) para la detección de disfunción ejecutiva en demencias. Neurología. 2013;28:457–476.

![Results from EB25 in controls and in patients with AD or FTD. Comparison of total EB25 results for control, AD, and TFD groups (ANOVA [F3,131]=58.33; P<.001). Boxes indicate means (central line), the 25th percentile (the lower edge of the box) and the 75th percentile (the upper edge of the box). Bars show the 10th percentile (lowest mark) and the 90th percentile (highest mark) for each group. FTD, frontotemporal dementia; AD, Alzheimer disease. Results from EB25 in controls and in patients with AD or FTD. Comparison of total EB25 results for control, AD, and TFD groups (ANOVA [F3,131]=58.33; P<.001). Boxes indicate means (central line), the 25th percentile (the lower edge of the box) and the 75th percentile (the upper edge of the box). Bars show the 10th percentile (lowest mark) and the 90th percentile (highest mark) for each group. FTD, frontotemporal dementia; AD, Alzheimer disease.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/21735808/0000002800000008/v1_201311230108/S2173580813001326/v1_201311230108/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr3.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)