Brief cognitive tests (BCT) are used in primary care (PC) for the detection of cognitive impairment (CI). Still, there are little data on their diagnostic utility (DU) in a community setting. This work evaluates the DU at the population level of Fototest, T@M, AD8 questionnaire and MMSE. It provides new cut-off points (CoP) validated in a CI early detection program.

Material and methodsIn the population and validation samples, the evaluation was carried out in two phases, a first of screening and administration of BCT and a second of clinical diagnosis, blinded to the results of the BCT, applying the current NIA-AA criteria. The DU of BCT in the population sample was evaluated with the area under the ROC curve (aROC). Youden index and the CoP with the best specificity that ensured a sensitivity of 80% were used to decide on the most appropriate CoP. The sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values for these CoP were calculated in the validation sample.

Results260 participants (23.1% with CI) from the population sample and 177 (42.4% with CI) from the validation sample were included. The Fototest has the best UD at the population level (aROC 0.851), which improves with the combination of Fototest and AD8 (aROC 0.875). The proposed CoP are AD8 ≥ 1, Fototest ≤ 35, T@M ≤ 40, and MMSE ≤ 26.

ConclusionBCT are helpful in detecting CI in PC. This work supports the use of more demanding PoC.

Los test cognitivos breves (TCB) se utilizan en atención primaria (AP) para la detección de deterioro cognitivo (DC) pero existen pocos datos sobre su utilidad diagnóstica (UD) en el ámbito comunitario.

Este trabajo evalúa la UD de Fototest, T@M, cuestionario AD8 y MMSE en una muestra representativa de la población y aporta nuevos puntos de corte (PdC) que se han validado en un grupo de personas que consultan por quejas cognitivas.

Material y métodosAmbas muestras, la poblacional y la de validación, se realizó una evaluación en dos fases; una primera de cribado y administración de los TCB y una segunda de diagnóstico clínico, ciego a los resultados de los TCB, aplicando los criterios NIA-AA actuales.

La UD de los TCB en la muestra poblacional se evaluó con el área bajo la curva ROC (aROC). Para elegir los PdC óptimos, se evaluaron dos métodos: el índice de Youden y el PdC con mejor especificidad que asegurase una sensibilidad del 80%. En la muestra de validación se calcularon los parámetros de sensibilidad, especificidad, y valores predictivos para estos PdC.

ResultadosSe han incluido 260 participantes (23,1% con DC) de la muestra poblacional y 177 (42,4% con DC) de la de validación. El Fototest tiene la mejor UD a nivel poblacional (aROC 0,851), que mejora con la combinación de Fototest y AD8 (aROC 0,875; p < 0,05). Los PdC propuestos son AD8 ≥ 1, Fototest ≤ 35, T@M ≤ 40 y MMSE ≤ 26.

ConclusiónLos TCB son útiles en la detección de DC en AP. Este trabajo apoya el uso de PdC más exigentes.

The prevalence of cognitive impairment is increasing as a result of population ageing, which poses a substantial challenge for healthcare systems.1 Today, dementia is the leading cause of dependence in the elderly population. Furthermore, its prevalence is expected to double in 20 years’ time,2 which will have significant social and economic implications.

Cognitive complaints are a frequent reason for consultation among older adults. Adequate, timely management of cognitive impairment is essential for patients and the healthcare system, enabling the provision of medical care and social support and helping in decision-making. However, diagnosis is often challenging, with most patients being diagnosed with cognitive impairment once they have already developed dementia.3 Primary care physicians follow standardised strategies to determine whether a patient with cognitive complaints requires specialist assessment. Brief cognitive tests (BCT) constitute a valuable tool in this scenario.4–6

However, the cut-off points used to determine cognitive impairment are often established in studies validating and evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of these tests in specialised settings, where cognitive impairment is much more prevalent and usually more severe than in primary care consultations.3,7 This may have an impact on the expected performance, external validity, and reproducibility of BCTs, resulting in a large number of false negatives. Several studies have underscored the need to update the cut-off scores of the most frequently used BCTs,4,8 such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), for detecting cognitive impairment from early stages, and to review the diagnostic accuracy of the MMSE in the clinical context.9 Such other BCTs as the Fototest,10–12 the Memory Alteration Test (M@T),13,14 and the AD8 questionnaire15 have shown adequate performance in detecting cognitive impairment,16 although little information is available on their use at the population level.

This study aims to determine the diagnostic accuracy of the MMSE and to compare it against other BCTs used in our setting, as well as updating cut-off scores in the general population for subsequent evaluation in the primary care setting.

Materials and methodsDesignWe conducted a study for the validation of diagnostic tests, which was conducted in 2 stages and using 2 different samples. The first group included a representative sample of volunteers and was used to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of BCTs and to establish the optimal cut-off scores. The second sample included patients with cognitive complaints and was used to evaluate the appropriateness of the cut-off scores selected.

Study population- 1)

Population sample: To assess the diagnostic accuracy of the BCTs, we used a sample drawn from the STOP ALZHEIMER 2020 - DEBA project. This is a cross-sectional epidemiological study of the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), dementia, and Alzheimer disease in individuals over 60 years of age conducted in Deba (Basque Country) in 2015 (Fig. 1). A communication campaign was performed in Deba to provide information on the project and raise awareness of cognitive impairment; subsequently, all individuals aged over 60 years were invited to participate in the study. A total of 678 individuals participated in the screening phase, where we gathered sociodemographic data; Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Dementia (CAIDE) risk score17; AD8 questionnaire results; and Fototest score. All participants with positive results in any of the cognitive tests (n = 168) were invited to participate in the study. We also invited age-, sex-, education-, and CAIDE-matched individuals with negative screening test results (Supplementary Table 1). The diagnostic process started at the primary care centre of Deba: a total of 337 individuals (123 with positive and 214 with negative screening test results) were administered the MMSE and M@T, provided information on previous diagnoses and current medication, and gave a sample for blood analysis. Of these, 277 (94 with positive and 183 with negative screening test results) completed the assessment at the CITA-Alzheimer foundation.

- 2)

Validation sample: The validation study used data from a cross-sectional study included in the GOIZ ALZHEIMER programme, a programme for early management of cognitive impairment conducted in the town of Beasain (Basque Country) in 2017. After a public awareness campaign on cognitive impairment and early diagnosis, all individuals older than 60 years with cognitive complaints or concern about their cognitive status were offered an initial assessment. During the initial assessment, we gathered sociodemographic data and the CAIDE dementia risk score, and administered the MMSE, M@T, Fototest, and AD8. Participants showing abnormal results on any of these BCTs were offered a thorough diagnostic evaluation including a neurological and neuropsychological assessment (Fig. 2). Of the 509 individuals with cognitive complaints who participated in the programme, 255 had positive cognitive screening test results, 180 of whom completed the diagnostic evaluation. Participants with negative screening test results did not undergo further cognitive assessment, but their electronic medical records were reviewed after 2 years, finding no additional consultations due to cognitive complaints or diagnosis of cognitive impairment.

Definition of positive screening test result: scores on any of the BCTs used that are suggestive of cognitive impairment according to the original cut-off scores.

Variables gathered during the diagnostic stage: In both samples, we gathered sociodemographic data, neurological examination results, physical examination results, and neuropsychiatric assessment results. The neuropsychological assessment evaluated premorbid intelligence, memory, language, constructional praxis, visuoperceptive skills, attention/concentration, and executive function. We obtained the following MRI sequences: T1 MPRAGE, axial T2-weighted, axial FLAIR, axial diffusion-weighted, and axial SWI.

Diagnostic criteria: Participants in both groups were classified, from a clinical viewpoint, into 3 groups: normal cognitive function, MCI, and dementia. Diagnosis was established by consensus between the medical team (a general practitioner, 2 neurologists, and a radiologist) and the neuropsychology team. The healthcare professionals establishing the diagnosis were blinded to BCT results. Diagnosis of dementia and MCI was based on the standard diagnostic criteria (NIA-AA criteria).18 Patients with MCI or dementia were considered to have cognitive impairment.

Brief cognitive testsMini-Mental State Examination: The MMSE is traditionally the most frequently used BCT. It is used in the initial assessment of cognitive function at many primary care and specialist consultations. MMSE scores are even used as an inclusion criterion in many studies. It takes approximately 10 minutes to administer. A cut-off score of 24 points is generally used to establish normal cognition.5,19 Numerous population studies have evaluated its performance for detecting dementia, but information on its ability to discriminate MCI is limited.20

Memory Alteration Test: More recently, the M@T was designed to detect changes in patients with an amnestic profile of cognitive impairment. Administration time is approximately 10 minutes, and the cut-off score is ≤ 37 points. The data currently available in our setting are from studies conducted in specialised units.13,14

Fototest: The Fototest takes 3–4 minutes to administer and is not influenced by education level. The test includes a naming task, a verbal fluency task, and a free and cued recall task. In our setting, it has shown superior diagnostic effectiveness to that of the MMSE.21,22 In this study, we used a cut-off score of 29 points, based on previous reviews.11

AD8 questionnaire: The AD8 questionnaire is a brief informant interview that contains 8 yes/no questions evaluating intraindividual changes23; the cut-off score is ≥ 2 points. The administration time is 2–3 minutes. It provides an overview of the patient’s progression, minimising the risk of biases related to age, sex, level of education, or sociocultural factors. In this study, we used the Spanish-language version of the questionnaire, which has a good correlation with other widely used functional scales, such as the Clinical Dementia Rating scale.15

Combination of Fototest and AD8 questionnaire: The combination of Fototest and AD8 scores has been found to improve the diagnostic capacity of either test in isolation.15 The combined score is calculated by subtracting the AD8 score from the Fototest score. The cut-off score is 26 points.

Protocol and informed consent: the STOP ALZHEIMER 2020 - DEBA project and the GOIZ ALZHEIMER programme were approved by the ethics committee of the Basque Country (project no. PI2015153 and PI2016178, respectively). All patients signed informed consent forms before being included in the study.

Statistical analysisThe analysis included all participants who had completed the 4 BCTs and the comprehensive diagnostic evaluation. Firstly, we performed a descriptive analysis of both samples. Secondly, we calculated the diagnostic characteristics of each BCT for the population sample: sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values for the cut-off points recommended in the literature, and the area under the curve (AUC).24 The same analysis was performed in 2 age groups (< 75 and ≥ 75 years) to evaluate the impact of greater prevalence of cognitive impairment on the diagnostic performance of the tests. To determine the optimal cut-off scores, we used 2 different methods: the first method is selecting the cut-off point with the greatest specificity for a sensitivity of at least 80%, and the second makes use of the Youden index (J = specificity + sensitivity – 1).25 The Youden index is calculated for each point on the ROC curve and ranges from –1 to 1. A Youden index of 1 indicates that there are no false positives or false negatives. Therefore, to define the optimal cut-off point according to this method, we selected the point with the highest Youden index value. Each Youden index value presents sensitivity and specificity values that are associated with the cut-off point for which they are calculated. To validate these cut-off points, we evaluated their sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values in the validation sample. Changes in the AUCs obtained with different BCTs were analysed with the DeLong test.26 The DeLong test was performed with the MedCalc statistical software package for biomedical research.

ResultsWe included a total of 437 participants from the 2 studies; we obtained sociodemographic data, administered the 4 BCTs analysed, and performed a complete neurological examination, including a formal neuropsychological assessment of cognitive function (Table 1).

Descriptive data from the population and validation samples.

| Population sample | Validation sample | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Total (%) | 260 | 100.00% | 177 | 100.00% | ||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 69.9 (7.9) | 73.5 (6.9) | < .001 | |||

| Age | ||||||

| < 75 years | 201 | 77.31% | 101 | 57.10% | ||

| ≥ 75 years | 59 | 22.69% | 76 | 42.90% | < .001 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 127 | 48.85% | 104 | 58.80% | ||

| Women | 133 | 51.15% | 73 | 41.20% | .050 | |

| Years of schooling, mean (SD) | ||||||

| 9.85 (3.54) | 8.19 (1.85) | < .001 | ||||

| 1–5 years | 14 | 5.38% | 29 | 16.38% | ||

| 6–10 years | 145 | 55.77% | 112 | 63.28% | ||

| 11–15 years | 75 | 28.85% | 28 | 15.82% | ||

| ≥ 15 years | 19 | 7.31% | 8 | 4.52% | ||

| NA | 7 | 2.69% | 0 | 0.00% | < .001 | |

| CAIDE | ||||||

| < 9 points | 162 | 62.31% | 74 | 41.81% | ||

| ≥ 9 points | 87 | 33.46% | 103 | 58.19% | ||

| NA | 11 | 4.23% | 0 | 0.00% | < .001 | |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||||||

| MCI/dementia | 60 | 23.10% | 75 | 42.40% | ||

| No CI | 200 | 76.90% | 102 | 57.60% | <.001 | |

| < 75 years | ||||||

| MCI/dementia | 31 | 15.42% | 27 | 26.73% | ||

| No CI | 170 | 84.58% | 74 | 73.27% | .021 | |

| ≥ 75 years | ||||||

| MCI/dementia | 29 | 49.15% | 48 | 63.16% | ||

| No CI | 30 | 50.85% | 28 | 36.84% | .117 | |

CAIDE: Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Dementia Risk Score; CI: cognitive impairment; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; NA: not available; SD: standard deviation.

The population sample included 260 individuals (94 of whom had positive screening test results) who had completed the 4 BCTs and undergone the clinical diagnostic process. Mean age was 69.9 years, 51.15% of whom were women, with a mean of 9.85 years of schooling. Some 33.46% of the sample presented a high risk of dementia (≥ 9 points on the CAIDE dementia risk score). The percentage of participants with cognitive impairment was 23.10%. In the group of individuals aged ≥ 75 years, nearly half of the sample presented cognitive impairment (vs 15.42% in the group of individuals < 75 years of age).

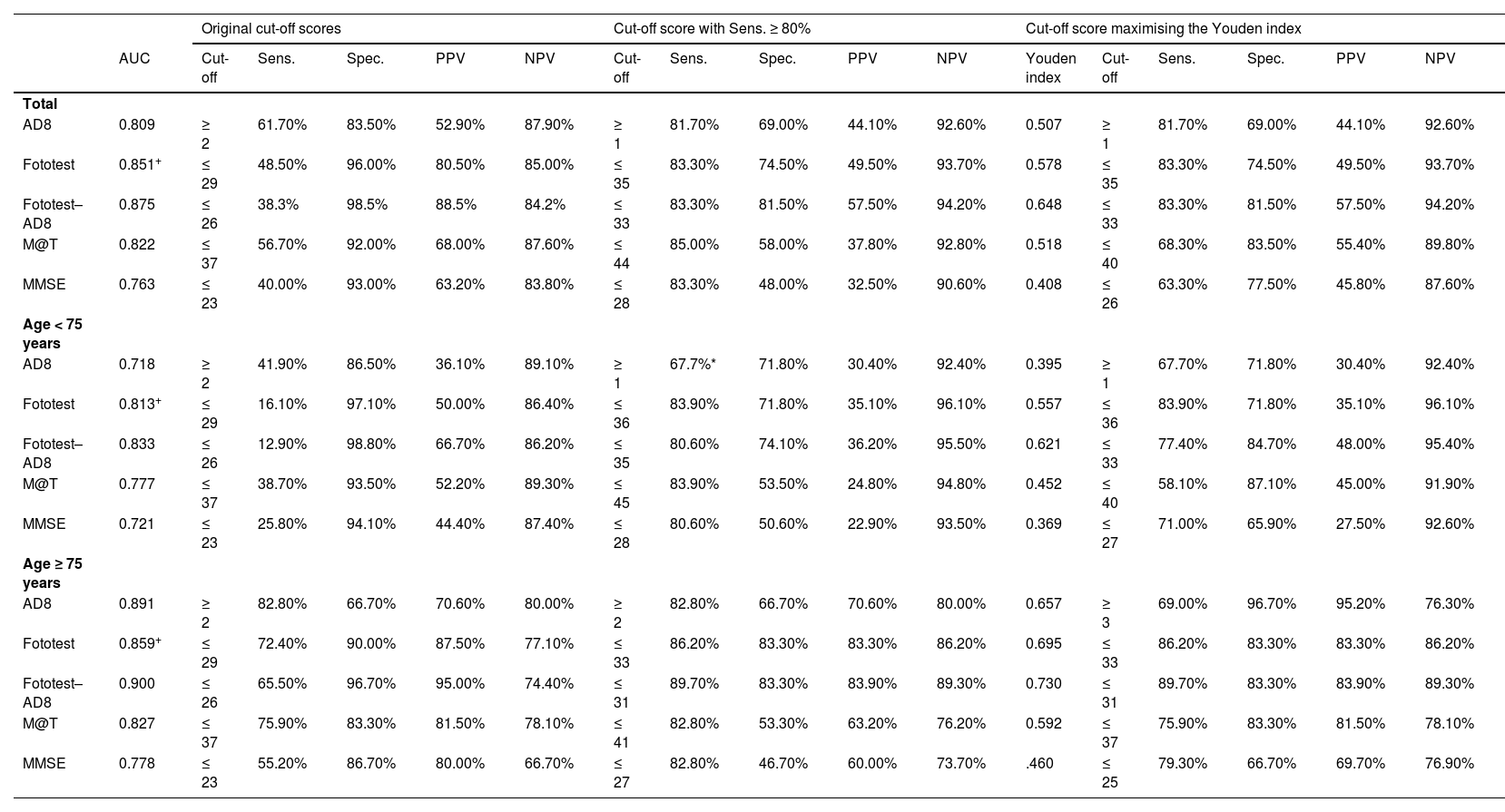

Table 2 presents the main parameters of diagnostic accuracy (AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values) for each BCT in the population sample. Given the higher prevalence of cognitive impairment among participants aged 75 years or older, we analysed the diagnostic accuracy of the tests in both age groups. The Fototest was the BCT with the highest discriminative ability, both in the whole sample and in the group of individuals younger than 75 years. Among participants aged 75 years or older, the test showing the highest discriminative ability was the AD8 questionnaire. The combination of the Fototest and the AD8 questionnaire obtained a significantly greater AUC value than either test alone. Fig. 3 presents these data graphically. Table 2 presents the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of the original cut-off points, the cut-off points with the highest specificity for a sensitivity of at least 80%, and the optimal cut-off points according to the Youden index. The cut-off points achieving a sensitivity of over 80% for the whole sample were as follows: MMSE ≤ 28, AD8 ≥ 1, M@T ≤ 44, Fototest ≤ 35, and Fototest–AD8 ≤ 33. According to the Youden index, the optimal cut-off points for the global sample are as follows: MMSE ≤ 26, AD8 ≥ 1, M@T ≤ 40, Fototest ≤ 35, and Fototest–AD8 ≤ 33.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and area under the curve of the original and proposed cut-off scores for each brief cognitive test in the population sample.

| Original cut-off scores | Cut-off score with Sens. ≥ 80% | Cut-off score maximising the Youden index | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | Cut-off | Sens. | Spec. | PPV | NPV | Cut-off | Sens. | Spec. | PPV | NPV | Youden index | Cut-off | Sens. | Spec. | PPV | NPV | |

| Total | |||||||||||||||||

| AD8 | 0.809 | ≥ 2 | 61.70% | 83.50% | 52.90% | 87.90% | ≥ 1 | 81.70% | 69.00% | 44.10% | 92.60% | 0.507 | ≥ 1 | 81.70% | 69.00% | 44.10% | 92.60% |

| Fototest | 0.851+ | ≤ 29 | 48.50% | 96.00% | 80.50% | 85.00% | ≤ 35 | 83.30% | 74.50% | 49.50% | 93.70% | 0.578 | ≤ 35 | 83.30% | 74.50% | 49.50% | 93.70% |

| Fototest–AD8 | 0.875 | ≤ 26 | 38.3% | 98.5% | 88.5% | 84.2% | ≤ 33 | 83.30% | 81.50% | 57.50% | 94.20% | 0.648 | ≤ 33 | 83.30% | 81.50% | 57.50% | 94.20% |

| M@T | 0.822 | ≤ 37 | 56.70% | 92.00% | 68.00% | 87.60% | ≤ 44 | 85.00% | 58.00% | 37.80% | 92.80% | 0.518 | ≤ 40 | 68.30% | 83.50% | 55.40% | 89.80% |

| MMSE | 0.763 | ≤ 23 | 40.00% | 93.00% | 63.20% | 83.80% | ≤ 28 | 83.30% | 48.00% | 32.50% | 90.60% | 0.408 | ≤ 26 | 63.30% | 77.50% | 45.80% | 87.60% |

| Age < 75 years | |||||||||||||||||

| AD8 | 0.718 | ≥ 2 | 41.90% | 86.50% | 36.10% | 89.10% | ≥ 1 | 67.7%* | 71.80% | 30.40% | 92.40% | 0.395 | ≥ 1 | 67.70% | 71.80% | 30.40% | 92.40% |

| Fototest | 0.813+ | ≤ 29 | 16.10% | 97.10% | 50.00% | 86.40% | ≤ 36 | 83.90% | 71.80% | 35.10% | 96.10% | 0.557 | ≤ 36 | 83.90% | 71.80% | 35.10% | 96.10% |

| Fototest–AD8 | 0.833 | ≤ 26 | 12.90% | 98.80% | 66.70% | 86.20% | ≤ 35 | 80.60% | 74.10% | 36.20% | 95.50% | 0.621 | ≤ 33 | 77.40% | 84.70% | 48.00% | 95.40% |

| M@T | 0.777 | ≤ 37 | 38.70% | 93.50% | 52.20% | 89.30% | ≤ 45 | 83.90% | 53.50% | 24.80% | 94.80% | 0.452 | ≤ 40 | 58.10% | 87.10% | 45.00% | 91.90% |

| MMSE | 0.721 | ≤ 23 | 25.80% | 94.10% | 44.40% | 87.40% | ≤ 28 | 80.60% | 50.60% | 22.90% | 93.50% | 0.369 | ≤ 27 | 71.00% | 65.90% | 27.50% | 92.60% |

| Age ≥ 75 years | |||||||||||||||||

| AD8 | 0.891 | ≥ 2 | 82.80% | 66.70% | 70.60% | 80.00% | ≥ 2 | 82.80% | 66.70% | 70.60% | 80.00% | 0.657 | ≥ 3 | 69.00% | 96.70% | 95.20% | 76.30% |

| Fototest | 0.859+ | ≤ 29 | 72.40% | 90.00% | 87.50% | 77.10% | ≤ 33 | 86.20% | 83.30% | 83.30% | 86.20% | 0.695 | ≤ 33 | 86.20% | 83.30% | 83.30% | 86.20% |

| Fototest–AD8 | 0.900 | ≤ 26 | 65.50% | 96.70% | 95.00% | 74.40% | ≤ 31 | 89.70% | 83.30% | 83.90% | 89.30% | 0.730 | ≤ 31 | 89.70% | 83.30% | 83.90% | 89.30% |

| M@T | 0.827 | ≤ 37 | 75.90% | 83.30% | 81.50% | 78.10% | ≤ 41 | 82.80% | 53.30% | 63.20% | 76.20% | 0.592 | ≤ 37 | 75.90% | 83.30% | 81.50% | 78.10% |

| MMSE | 0.778 | ≤ 23 | 55.20% | 86.70% | 80.00% | 66.70% | ≤ 27 | 82.80% | 46.70% | 60.00% | 73.70% | .460 | ≤ 25 | 79.30% | 66.70% | 69.70% | 76.90% |

AD8: Alzheimer Disease 8 questionnaire; AUC: area under the curve; M@T: Memory Alteration Test; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; Sens.: sensitivity; Spec.: specificity.

The validation sample included 177 participants. Mean age was slightly higher (73.5 years), and 41.20% were women. Participants in this group also had a slightly lower education level (mean of 8.19 years of schooling), and 58.19% presented a high risk of dementia according to the CAIDE dementia risk score. The prevalence of cognitive impairment in this group was 42.40%. Cognitive impairment was more frequent among individuals aged ≥ 75 years than in those aged < 75 years (63.16% vs 26.73%).

Table 3 presents the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of each BCT in the validation sample for the cut-off points obtained in the population sample achieving at least 80% sensitivity, as well as the cut-off points maximising the Youden index.

Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the optimal cut-off scores established with 2 different methods in the validation sample.

| Cut-off score with ≥ 80% Sens. obtained in the population sample | Cut-off score maximising the Youden index obtained in the population sample | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off | Sens. | Spec. | PPV | NPV | Cut-off | Sens. | Spec. | PPV | NPV | |

| Total | ||||||||||

| AD8 | ≥ 1 | 74.70% | 52.90% | 53.80% | 74.00% | ≥ 1 | 74.70% | 52.90% | 53.80% | 74.00% |

| Fototest | ≤ 35 | 84.00% | 54.90% | 57.80% | 82.40% | ≤ 35 | 84.00% | 54.90% | 57.80% | 82.40% |

| Fototest–AD8 | ≤ 33 | 82.70% | 58.80% | 59.60% | 82.20% | ≤ 33 | 82.70% | 58.80% | 59.60% | 82.20% |

| M@T | ≤ 44 | 100.00% | 4.90% | 43.60% | 100.00% | ≤ 40 | 97.30% | 17.60% | 46.50% | 90.00% |

| MMSE | ≤ 28 | 96.00% | 24.50% | 48.30% | 89.30% | ≤ 26 | 73.30% | 71.60% | 65.50% | 78.50% |

| Age < 75 years | ||||||||||

| AD8 | ≥ 1 | 66.70% | 52.70% | 34.00% | 81.30% | ≥ 1 | 66.70% | 52.70% | 34.00% | 81.30% |

| Fototest | ≤ 36 | 74.10% | 47.30% | 33.90% | 83.30% | ≤ 36 | 74.10% | 47.30% | 33.90% | 83.30% |

| Fototest–AD8 | ≤ 35 | 74.10% | 51.40% | 35.70% | 84.40% | ≤ 33 | 66.70% | 64.90% | 40.90% | 84.20% |

| M@T | ≤ 45 | 100.00% | 5.40% | 27.80% | 100.00% | ≤ 40 | 96.30% | 21.60% | 31.00% | 94.10% |

| MMSE | ≤ 28 | 96.30% | 28.40% | 32.90% | 95.50% | ≤ 27 | 88.90% | 52.70% | 40.70% | 92.90% |

| Age ≥ 75 years | ||||||||||

| AD8 | ≥ 2 | 58.30% | 71.40% | 77.80% | 50.00% | ≥ 3 | 37.50% | 78.60% | 75.00% | 42.30% |

| Fototest | ≤ 33 | 85.40% | 42.90% | 71.90% | 63.20% | ≤ 33 | 85.40% | 42.90% | 71.90% | 63.20% |

| Fototest–AD8 | ≤ 31 | 83.30% | 42.90% | 71.40% | 60.00% | ≤ 31 | 83.30% | 42.90% | 71.40% | 60.00% |

| M@T | ≤ 41 | 100.00% | 7.10% | 64.90% | 100.00% | ≤ 37 | 91.70% | 14.30% | 64.70% | 50.00% |

| MMSE | ≤ 27 | 85.40% | 39.30% | 70.70% | 61.10% | ≤ 25 | 64.60% | 78.60% | 83.80% | 56.40% |

AD8: Alzheimer Disease 8 questionnaire; M@T: Memory Alteration Test; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; Sens.: sensitivity; Spec.: specificity.

This study evaluates the diagnostic accuracy of 4 BCTs using reference data from a population sample; the proposed cut-off scores were subsequently validated in a clinical sample. The cut-off scores obtained in this study are different from those established by previous studies, which have used clinical samples from specialised settings. The Fototest was found to be the BCT that best discriminated between individuals with and without cognitive impairment. Furthermore, it showed even higher diagnostic accuracy when combined with the AD8 questionnaire, as has previously been suggested.15 Our results may contribute to improving the detection of cognitive impairment in the primary care setting. The diagnostic accuracy values and cut-off points established in this study may help healthcare professionals to select the most appropriate screening tool for individuals with cognitive complaints.

Unlike previous studies using samples from specialist consultations, we evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of BCTs in the general population; this explains the higher cut-off points established in our study. The fact that our sample was drawn from the general population suggests that the cut-off points proposed in our study are more appropriate for the primary care setting and in the initial assessment of patients with cognitive complaints. Our sample is representative of the general population of our setting in terms of age and sex (Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2).

Diagnosis of cognitive impairment was established after completion of an extensive diagnostic protocol including a thorough neuropsychological assessment of all cognitive domains, applying the NIA-AA diagnostic criteria. Another strength of this study is the fact that cut-off scores were validated in a sample of individuals drawn from the general population, which is representative of the type of patient requesting a primary care consultation due to cognitive complaints.

Sensitivity and specificity values, and particularly predictive values, depend on the prevalence of a disease (cognitive impairment in this case) in the population under study. In the case of the BCTs evaluated, the cut-off scores proposed in the literature were calculated using samples drawn from specialist consultations,5,11,13 which show a higher prevalence of cognitive impairment than the population attending primary care consultations. Given that BCTs are mainly used in the initial assessment of patients with cognitive complaints, we believed it necessary to determine whether cut-off scores obtained from the general population are similar to those published in the literature. Our results demonstrate that this is not the case, as the cut-off scores obtained in our study are higher and, consequently, stricter. This is relevant considering that one of the main objectives of initial diagnostic strategies in primary care is to avoid obtaining negative results in patients who do have a condition. As shown in this study, the application of the original cut-off scores in a population sample showed high specificity but low sensitivity (Table 2) and a higher number of false negatives.

In this study, we used 2 different methods for estimating the optimal cut-off scores with a view to detecting cases of cognitive impairment in the primary care setting. The first method consists of selecting the cut-off score with the highest specificity for a sensitivity of at least 80%. The second method makes use of the Youden index, which results from combining sensitivity and specificity, placing emphasis on the test’s rate of correct classifications.25 Both methods yield the same cut-off scores for the Fototest and the AD8 questionnaire. However, in the case of the M@T and the MMSE, low specificity values were required to achieve ≥ 80% sensitivity. This was observed in the population sample (DEBA project) and confirmed in the validation sample (GOIZ-ALZHEIMER project). Based on our data, we would recommend using the cut-off scores that maximise the Youden index (AD8 ≥ 1, Fototest ≤ 35, M@T ≤ 40, and MMSE ≤ 26) for detecting cognitive impairment in the primary care setting, as these present better specificity values while achieving high sensitivity.

The higher prevalence of cognitive impairment at older ages justified the evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of the BCTs in 2 age groups (< 75 and ≥ 75 years). For individuals younger than 75 years, these cut-off points should be even stricter, given the lower prevalence of cognitive impairment in this age group. The AD8 questionnaire was the BCT showing the highest discriminative ability in the group of individuals aged ≥ 75 years, but obtained the poorest results among participants aged < 75 years. This finding supports the idea that informant perceptions of a patient’s cognitive status are extremely valuable for final diagnosis.

The main limitation of our study was the low participation rate, due to the logistical difficulty of getting participants to complete all screening and diagnostic procedures. In fact, in order to gather the highest possible number of participants, our research team travelled to participants’ places of residence to complete the screening process. Our participants presented similar demographic characteristics regardless of whether they completed the assessment at the CITA-Alzheimer foundation (Supplementary Table 1). In the validation sample, to compensate for the fact that individuals showing normal cognition in the screening phase did not undergo further diagnostic assessment, we reviewed their clinical histories 2 years later, finding no records of subsequent consultations due to cognitive complaints or diagnosis of cognitive impairment.

The assessment of patients with cognitive complaints varies greatly depending on the resources (mainly time) available during consultations and the experience of the physician. Our study is intended to assist primary care physicians in creating simple strategies to manage cognitive complaints and to determine when to refer patients to a specialist consultation. The comparisons made in this study between the BCTs most frequently used in our setting are not intended to favour or discredit any of them. We believe that no single test can be considered superior to the others or is able to correctly identify every single case of cognitive impairment. Furthermore, each BCT provides different and complementary information. Thus, while the MMSE evaluates several cognitive domains and may be useful for initial assessment, the M@T evaluates a single domain and may be particularly useful in patients reporting memory problems only. The Fototest is especially interesting for the initial assessment of patients with cognitive complaints as it provides an efficient measure of language and memory performance that is not influenced by such factors as level of education. Lastly, the AD8 questionnaire provides valuable, structured data on an informant’s impressions of the patient’s cognitive status. Our results underscore the need to use stricter cut-off scores for cognitive impairment. This is consistent with previous studies reporting normative data from neurological patients without cognitive impairment,27 which also propose higher cut-off scores than the values initially proposed.

According to our results, the Fototest and the AD8 questionnaire, and especially the combination of both, achieve the best negative predictive value for the initial assessment of patients with cognitive complaints in primary care. Regarding the likelihood of correctly classifying patients with and without cognitive impairment (AUC), applying the same cut-off scores, the Fototest and the AD8 questionnaire were again the BCTs with the best results. Both instruments are straightforward and take a maximum of 5 minutes to administer. The AD8 questionnaire may be completed by the patient’s companion at the consultation while the Fototest is being administered to the patient; this is an interesting strategy in primary care consultations, where time is limited.

The diagnostic accuracy of the MMSE, the most frequently used BCT in primary care, is good, yet inferior to that of the other BCTs analysed. In primary care, it may therefore be replaced by other tests,28 such as the Fototest, which presents better diagnostic performance29,30 and cost-effectiveness.22

The M@T also presents good diagnostic accuracy with very high sensitivity; however, half of the individuals with abnormal scores did not have cognitive impairment. As this test nearly exclusively evaluates memory, it may be used at specialised consultations or in subsequent assessments, as the higher prevalence of cognitive impairment in these contexts improves the test’s diagnostic accuracy.

ConclusionsThis study evaluates the diagnostic accuracy of the Fototest, AD8 questionnaire, M@T, and MMSE in a population sample and subsequently in a sample of individuals attended at primary care consultations. The Fototest and the combination of the Fototest plus the AD8 questionnaire show the highest discriminative ability, and may therefore be useful in primary care settings. We propose stricter cut-off scores that improve the sensitivity values of the tools most frequently used in the initial assessment of individuals with cognitive complaints.

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind. The DEBA project was partially funded by the local government of Gipuzkoa (2016 Support Programme for the Gipuzkoa Network for Science, Technology, and Innovation) and the Basque regional government (record 2016111096, 2016 grant for health research projects).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This study has not been presented at any meeting or conference.

We would like to thank the participants in the DEBA and GOIZ ALZHEIMER BEASAIN projects for their time and cooperation. We also wish to thank the municipalities of Deba and Beasain (Gipuzkoa, Basque Country) for their collaboration.

Members of the DEBA project: Álvarez I, Álvarez AI, Beltrán Iguiño A, Bilbao M, Garmendia ME, González-Martin L, Ibarbia AM, Sanzo JM, Tapia A, Villaverde FJ.

Members of the GOIZ ALZHEIMER BEASAIN project: Aquizu I, Arrondo MA, Baztarrika E, Etxeberria L, García-Arrea E, García-Domínguez M, Imaz E, Iparragirre M, Iridoy M, Larrea A, López MD, Martin F, Olaskoaga A, Pacheco P, Pérez-Rodiguez AM, Porres Y, Ruibal M, San Juan B, Tilves MJ, Zapirain E.

Representing the DEBA Project Working Group.

The names of the components of the DEBA Project Working Group and the GOIZ Alzheimer Beasain Working Group are listed in Appendix A.