We read with great interest the Letter to the Editor by Martínez-Sellés1 on the article “Prevalence of neurological complications in infective endocarditis.”2

In response to his comments, the aims of this reply are to analyse in greater depth the comorbidities observed in the patients included in the initial study and to underscore the importance of early antibiotic treatment to reduce the incidence of neurological complications in infective endocarditis (IE).

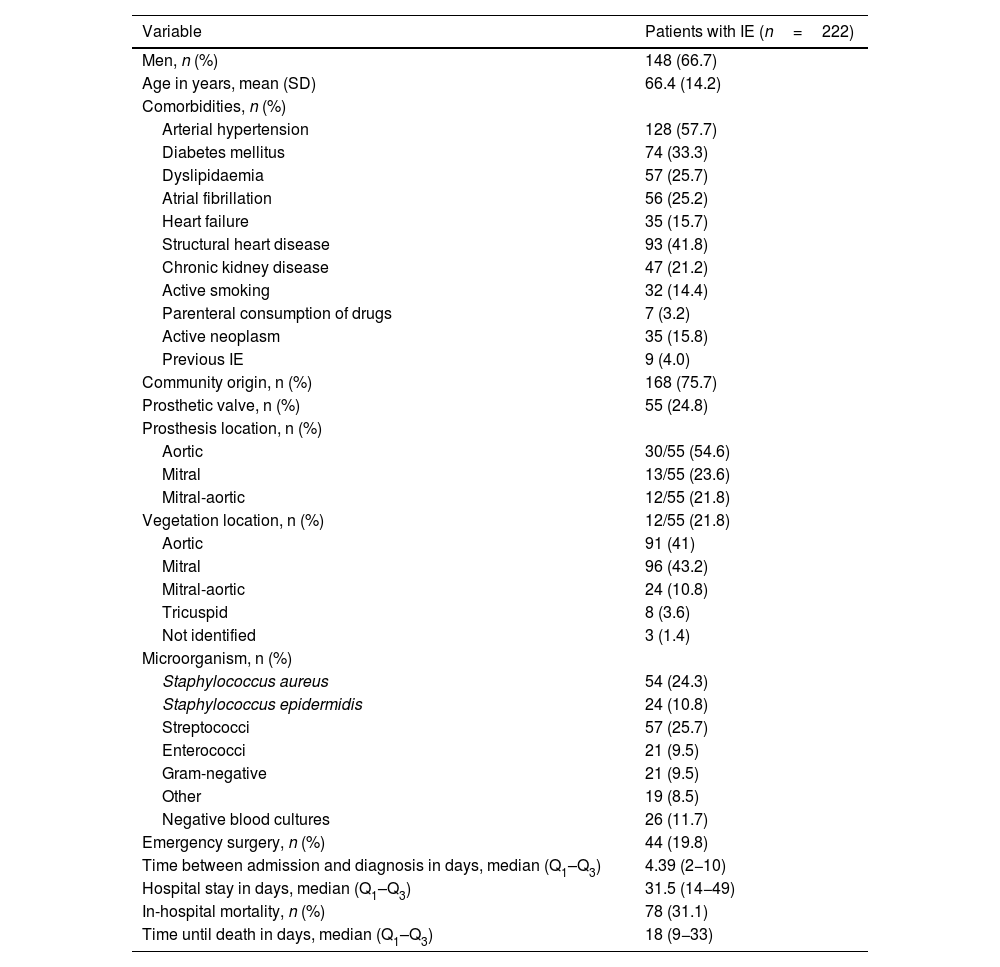

The retrospective cohort study included 222 patients diagnosed with IE according to the modified Duke criteria.3 The study population showed a predominance of men in the sixth decade of life presenting mainly aortic and mitral valve involvement. Demographic, clinical, and microbiological variables are shown in Table 1. We should underscore arterial hypertension as the most frequent comorbidity, affecting 128 patients (57.7%), followed by structural heart disease in 93 patients (41.8%), and diabetes mellitus (DM) in 74 (33.3%). A total of 9 patients (4%) presented recurrent endocarditis4, defined as a new episode of IE 2 months after completion of the antibiotic treatment.

Demographic, clinical, and microbiological variables in patients with infective endocarditis.

| Variable | Patients with IE (n=222) |

|---|---|

| Men, n (%) | 148 (66.7) |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 66.4 (14.2) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Arterial hypertension | 128 (57.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 74 (33.3) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 57 (25.7) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 56 (25.2) |

| Heart failure | 35 (15.7) |

| Structural heart disease | 93 (41.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 47 (21.2) |

| Active smoking | 32 (14.4) |

| Parenteral consumption of drugs | 7 (3.2) |

| Active neoplasm | 35 (15.8) |

| Previous IE | 9 (4.0) |

| Community origin, n (%) | 168 (75.7) |

| Prosthetic valve, n (%) | 55 (24.8) |

| Prosthesis location, n (%) | |

| Aortic | 30/55 (54.6) |

| Mitral | 13/55 (23.6) |

| Mitral-aortic | 12/55 (21.8) |

| Vegetation location, n (%) | 12/55 (21.8) |

| Aortic | 91 (41) |

| Mitral | 96 (43.2) |

| Mitral-aortic | 24 (10.8) |

| Tricuspid | 8 (3.6) |

| Not identified | 3 (1.4) |

| Microorganism, n (%) | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 54 (24.3) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 24 (10.8) |

| Streptococci | 57 (25.7) |

| Enterococci | 21 (9.5) |

| Gram-negative | 21 (9.5) |

| Other | 19 (8.5) |

| Negative blood cultures | 26 (11.7) |

| Emergency surgery, n (%) | 44 (19.8) |

| Time between admission and diagnosis in days, median (Q1–Q3) | 4.39 (2−10) |

| Hospital stay in days, median (Q1–Q3) | 31.5 (14−49) |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 78 (31.1) |

| Time until death in days, median (Q1–Q3) | 18 (9−33) |

IE: infective endocarditis; Q1–Q3: quartiles 1 and 3; SD: standard deviation.

Modified from Rodríguez-Montolio et al.2

As described in the previous study2, ischaemic stroke was the most frequent neurological complication (35 patients, 15.8% of the total sample). Haemorrhagic stroke was the second most frequent complication (11 patients, 4.9%).

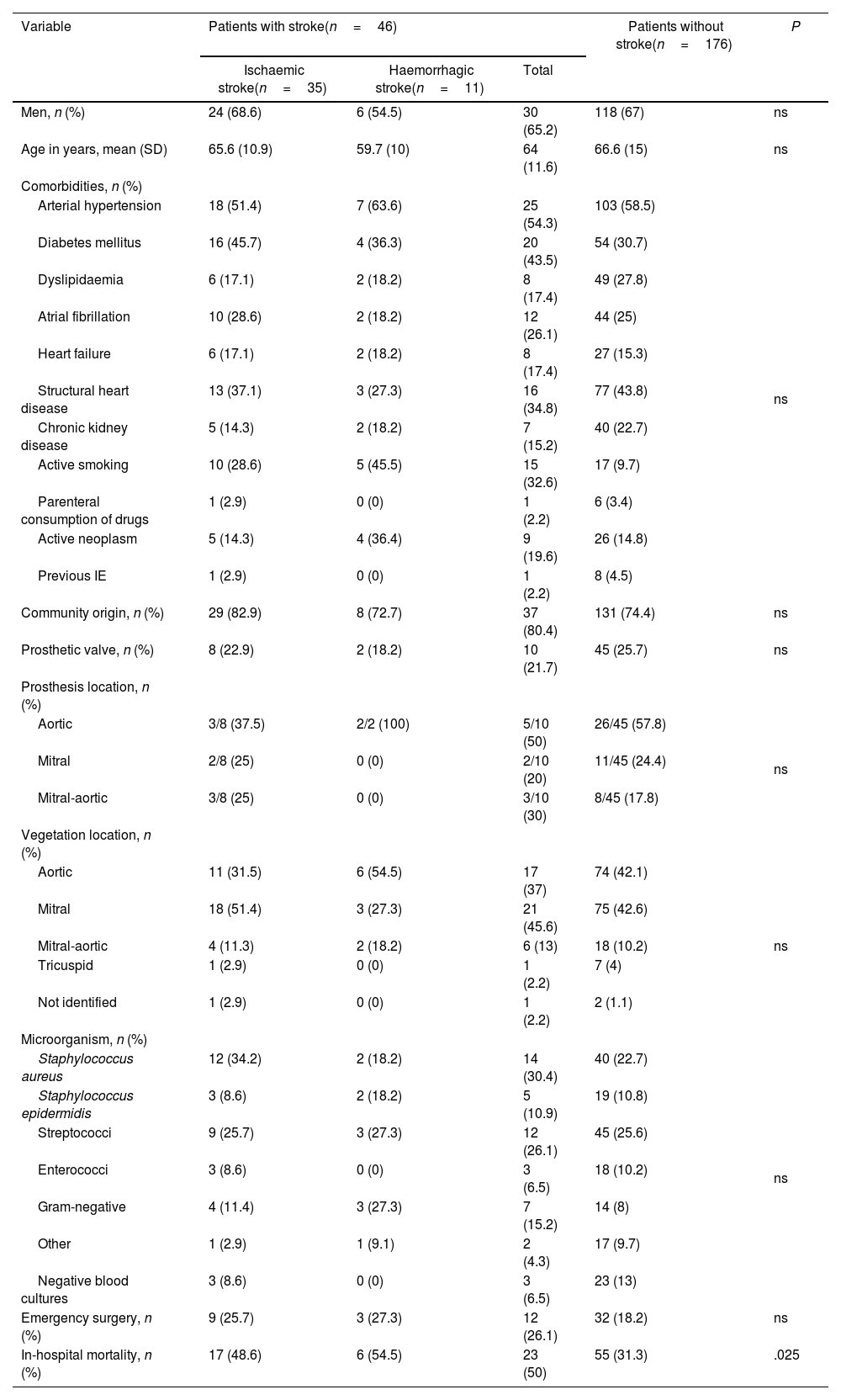

Table 2 compares demographic, clinical, and microbiological data in patients with and without stroke. A further analysis of patients’ clinical profiles revealed that the subgroup of patients with stroke (n=46) presented a higher prevalence of DM and smoking than the remaining patients (43.5% vs 30.7% and 32.6% vs 9.7%, respectively), although these differences were not statistically significant. In the subgroup of patients with ischaemic stroke (n=35), we more frequently observed Staphylococcus aureus infection as the pathogenic agent (34.2% vs 22.7%) and a more frequent involvement of the mitral valve (51.4% vs 42.6%), although these differences were not statistically significant.

Demographic, clinical, and microbiological variables in patients with infective endocarditis, by subgroup.

| Variable | Patients with stroke(n=46) | Patients without stroke(n=176) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischaemic stroke(n=35) | Haemorrhagic stroke(n=11) | Total | |||

| Men, n (%) | 24 (68.6) | 6 (54.5) | 30 (65.2) | 118 (67) | ns |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 65.6 (10.9) | 59.7 (10) | 64 (11.6) | 66.6 (15) | ns |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||

| Arterial hypertension | 18 (51.4) | 7 (63.6) | 25 (54.3) | 103 (58.5) | ns |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (45.7) | 4 (36.3) | 20 (43.5) | 54 (30.7) | |

| Dyslipidaemia | 6 (17.1) | 2 (18.2) | 8 (17.4) | 49 (27.8) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 10 (28.6) | 2 (18.2) | 12 (26.1) | 44 (25) | |

| Heart failure | 6 (17.1) | 2 (18.2) | 8 (17.4) | 27 (15.3) | |

| Structural heart disease | 13 (37.1) | 3 (27.3) | 16 (34.8) | 77 (43.8) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 (14.3) | 2 (18.2) | 7 (15.2) | 40 (22.7) | |

| Active smoking | 10 (28.6) | 5 (45.5) | 15 (32.6) | 17 (9.7) | |

| Parenteral consumption of drugs | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | 6 (3.4) | |

| Active neoplasm | 5 (14.3) | 4 (36.4) | 9 (19.6) | 26 (14.8) | |

| Previous IE | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | 8 (4.5) | |

| Community origin, n (%) | 29 (82.9) | 8 (72.7) | 37 (80.4) | 131 (74.4) | ns |

| Prosthetic valve, n (%) | 8 (22.9) | 2 (18.2) | 10 (21.7) | 45 (25.7) | ns |

| Prosthesis location, n (%) | |||||

| Aortic | 3/8 (37.5) | 2/2 (100) | 5/10 (50) | 26/45 (57.8) | ns |

| Mitral | 2/8 (25) | 0 (0) | 2/10 (20) | 11/45 (24.4) | |

| Mitral-aortic | 3/8 (25) | 0 (0) | 3/10 (30) | 8/45 (17.8) | |

| Vegetation location, n (%) | |||||

| Aortic | 11 (31.5) | 6 (54.5) | 17 (37) | 74 (42.1) | ns |

| Mitral | 18 (51.4) | 3 (27.3) | 21 (45.6) | 75 (42.6) | |

| Mitral-aortic | 4 (11.3) | 2 (18.2) | 6 (13) | 18 (10.2) | |

| Tricuspid | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | 7 (4) | |

| Not identified | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Microorganism, n (%) | |||||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 12 (34.2) | 2 (18.2) | 14 (30.4) | 40 (22.7) | ns |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 3 (8.6) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (10.9) | 19 (10.8) | |

| Streptococci | 9 (25.7) | 3 (27.3) | 12 (26.1) | 45 (25.6) | |

| Enterococci | 3 (8.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.5) | 18 (10.2) | |

| Gram-negative | 4 (11.4) | 3 (27.3) | 7 (15.2) | 14 (8) | |

| Other | 1 (2.9) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (4.3) | 17 (9.7) | |

| Negative blood cultures | 3 (8.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.5) | 23 (13) | |

| Emergency surgery, n (%) | 9 (25.7) | 3 (27.3) | 12 (26.1) | 32 (18.2) | ns |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 17 (48.6) | 6 (54.5) | 23 (50) | 55 (31.3) | .025 |

IE: infective endocarditis; ns: not significant; SD: standard deviation.

The in-hospital mortality rate was higher in the subgroup of patients with stroke (31.3% vs 50%, P=.025) and slightly higher in the group of patients with haemorrhagic stroke than in those with ischaemic stroke (54.5% vs 48.6%).

In terms of antibiotic treatment, all patients were treated with antimicrobial therapy in accordance with the recommendations of clinical practice guidelines3. Given the retrospective nature of the study and the lack of specific data for patients diagnosed prior to the implementation of electronic clinical records, we are unable to determine the distribution of the time of onset of neurological symptoms with regards to antibiotic therapy. However, we did observe that 35/46 patients (76.1%) presented neurological symptoms before antibiotic therapy onset or during the first days thereafter.

Neurological complications, and especially ischaemic stroke, are the most frequent extracardiac complications in IE and are associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality5–7. It is important to identify risk factors associated both with ischaemic and with haemorrhagic stroke in IE in order to optimise the early clinical management of patients and to improve their functional and vital prognosis.

Regarding ischaemic stroke, mitral valve involvement and the participation of S. aureus as aetiological agent have previously been identified as risk factors5–7. These data are similar to those described in our study, although we found no statistically significant association. We also underscore the higher prevalence of DM in the subgroup of patients with ischaemic stroke, as was observed in the study by Valenzuela et al.6 and in accordance with the comments by Martínez-Sellés1.

Regarding haemorrhagic stroke, the study by Valenzuela et al.6 identified male sex, rheumatic heart disease, and fungal infection as risk factors. In our study, we observed a higher percentage of smokers in this subgroup of patients, although smoking has not previously been described as a risk factor, and the difference was not statistically significant.

Embolic events are one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in IE, and usually occur before or during the first week of antibiotic therapy7. In our study, 76.1% of patients with stroke presented neurological symptoms before onset of antibiotic therapy or during the first days; similar data were reported by García-Cabrera et al.5 (86%) and Valenzuela et al.6 (80%). Given the previously described limitations of our study, we could not analyse the incidence and the decrease in neurological events during antibiotic therapy. However, other studies have shown that the risk of embolism decreases by approximately 50% after one week of effective antibiotic therapy; therefore, early treatment onset is fundamental3,7,8. We believe that a multidisciplinary approach to patients with IE is essential to optimising its management and treatment and to reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with the condition and its embolic complications.