Coma blisters are bullous skin lesions appearing in patients with low levels of consciousness. They were first described in 1812 by Larrey, a surgeon serving in the French army during Napoleon Bonaparte’s rule, in soldiers with carbon monoxide poisoning.

We present the case of a 53-year-old male smoker with poorly controlled arterial hypertension who visited the emergency department due to sudden loss of strength in the right limbs and impaired consciousness. A CT scan revealed an intracerebral haemorrhage measuring 57 × 34 mm in the left basal ganglia, in the context of a hypertensive crisis. The patient’s level of consciousness progressively worsened (Glasgow Coma Scale score of 8), and he required orotracheal intubation and sedation with propofol and fentanyl. The patient also presented abnormal movements and tremor, which resolved within 2 days with levetiracetam dosed at 1000 mg every 12 h.

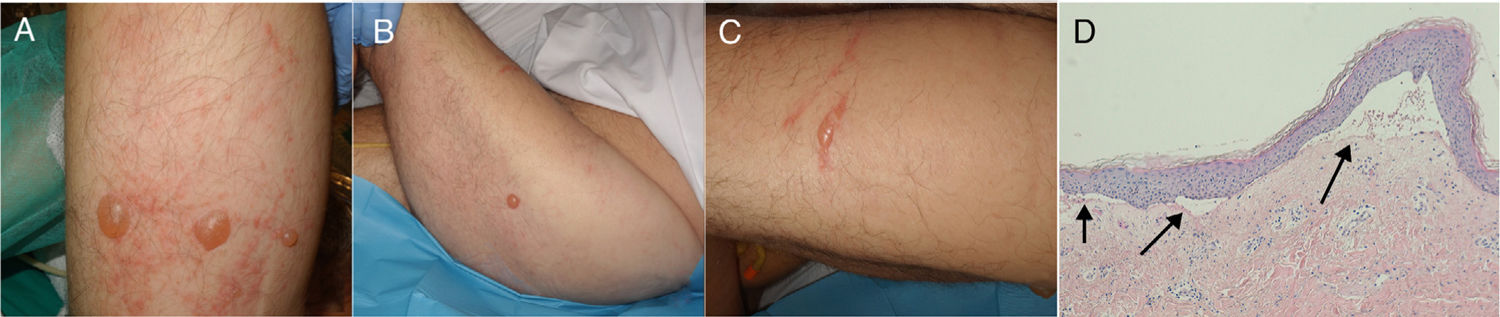

In this context, he presented skin lesions in such pressure areas as the posterior surface of the arms (Fig. 1A), the gluteal area, and the lateral surface of the thighs (Fig. 1B), but also in areas not receiving pressure, such as the anterolateral surface of the left thigh (Fig. 1C). The lesions were tense, clear blisters containing a yellowish fluid; some appeared over erythematous plaques. A biopsy of skin tissue from one of the lesions revealed a subepidermal blister with sparse inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 1D).

a) Blisters on the dorsal surface of the right arm, surrounded by erythema. B) Isolated blister on healthy skin on the lateral surface of the left thigh. C) Blister on the anterolateral surface of the left thigh. D) Biopsy of a lesion with haematoxylin-eosin staining (×10), showing the dermoepidermal junction (arrows), with sparse inflammatory infiltrate.

These findings led to a diagnosis of coma blisters (Table 1).

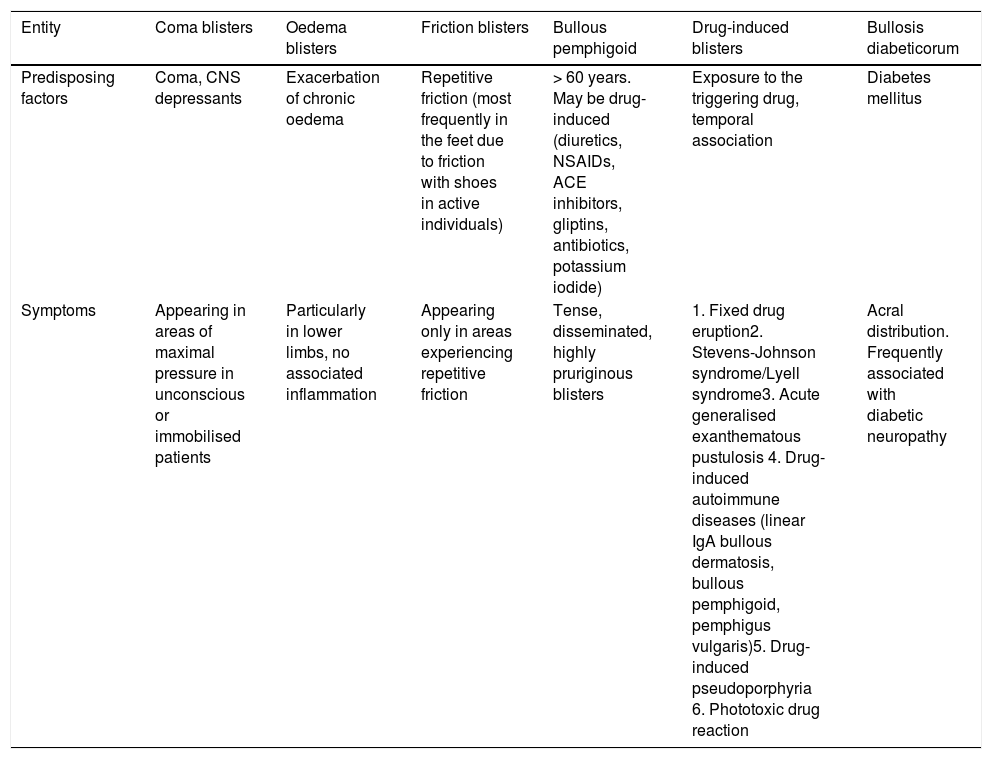

Main conditions to be included in the differential diagnosis of coma blisters.

| Entity | Coma blisters | Oedema blisters | Friction blisters | Bullous pemphigoid | Drug-induced blisters | Bullosis diabeticorum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | Coma, CNS depressants | Exacerbation of chronic oedema | Repetitive friction (most frequently in the feet due to friction with shoes in active individuals) | > 60 years. May be drug-induced (diuretics, NSAIDs, ACE inhibitors, gliptins, antibiotics, potassium iodide) | Exposure to the triggering drug, temporal association | Diabetes mellitus |

| Symptoms | Appearing in areas of maximal pressure in unconscious or immobilised patients | Particularly in lower limbs, no associated inflammation | Appearing only in areas experiencing repetitive friction | Tense, disseminated, highly pruriginous blisters | 1. Fixed drug eruption2. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/Lyell syndrome3. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis 4. Drug-induced autoimmune diseases (linear IgA bullous dermatosis, bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris)5. Drug-induced pseudoporphyria 6. Phototoxic drug reaction | Acral distribution. Frequently associated with diabetic neuropathy |

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Coma blisters are tense blisters appearing on healthy skin and/or erythematous macules and plaques in patients with impaired consciousness. Blisters vary in size, and may measure up to 4−5 cm; their content is usually serous and rarely bloody. They usually appear 24 hours after initiation of drug treatment, and 48−72 hours after onset of coma.

Coma blisters have traditionally been associated with overdose of CNS depressants, particularly barbiturates, tricyclic antidepressants, hypnotics, opiates, antipsychotics, and alcohol. Other less frequent scenarios include carbon monoxide poisoning; neurological conditions including cerebrovascular disease, head trauma, and viral encephalitis; and such metabolic alterations as hypoglycaemia, diabetic ketoacidosis, hypercalcaemia, and hepatic encephalopathy. Coma blisters have also been reported in non-comatose patients with severe neurological disease.1–5

In most cases, clinical findings are sufficient for diagnosis. In case of doubt, skin biopsy1,4 helps differentiate coma blisters from such other skin lesions as friction blisters and bullous drug eruptions. Table 1 lists the main conditions to be considered in the differential diagnosis of coma blisters.

We initially suspected that our patient’s lesions were caused by drug toxicity3 secondary to a pathogenic mechanism similar to that associated with other drug-induced skin reactions.6 This hypothesis is supported by the fact that these lesions often appear in the context of sedative overdose; these drugs are normally excreted through the sweat glands, which are typically necrotic in biopsy studies.4 However, as we mentioned previously, not all cases of coma blisters are drug-induced.1–5 It seems clear that pressure, friction, and local hypoxia are also involved, since most lesions appear in pressure sites and show vascular damage without significant inflammatory infiltrate.1,4 However, in some cases, as in the one presented here, lesions appear in areas receiving minimal pressure.

Direct immunofluorescence usually yields negative results; however, some patients display immunoglobulin and complement deposition both in the walls of dermal vessels and in keratinocytes. However, these pathogenic mechanisms are not considered to be immune-mediated, but rather nonspecific.1,4 In our patient, both direct and indirect immunofluorescence against anti-intercellular substance antibodies and epidermal basement membrane antibodies yielded negative results.

Therefore, our patient’s blisters can be attributed to coma secondary to a cerebrovascular event or to treatment (either CNS depressants [propofol and fentanyl] or antiepileptics [levetiracetam]), in spite of the short treatment duration (2 days), or even to a combination of both factors. Unfortunately, no test can demonstrate the involvement of either precipitating factor in isolation.

Coma blisters usually resolve spontaneously within 1–2 weeks, occasionally with residual scaling. In our patient, the lesions resolved within 2 weeks, with isolated blisters occasionally appearing until the patient regained consciousness. Frequent repositioning may help prevent and treat coma blisters.2

In conclusion, diagnosis of coma blisters is mainly clinical; the condition may be associated with underlying neurological disorders.

FundingThe authors have received no funding for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Torres-Navarro I, Pujol-Marco C, Roca-Ginés J, Botella-Estrada R. Ampollas por coma. Una clave para el diagnóstico neurológico. Neurología. 2020;35:512–513.