Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disease affecting nerve transmission at the level of the neuromuscular junction, and typically causes fluctuating muscle weakness. Epidemiological studies show an increase in MG prevalence, particularly among the older population.

ObjectiveWe performed a retrospective epidemiological study to determine the incidence and prevalence of MG in the province of Ourense (Galicia, Spain), characterised by population ageing.

Material and methodsPatients were selected from our clinical neuromuscular diseases database by searching for patients with an active prescription for pyridostigmine bromide. Incidence was estimated for the period 2009-2018. We calculated prevalence at 31/12/2018. According to census data for the province of Ourense, the population on 1/1/2019 was 307 651, of whom 96 544 (31.4%) were aged ≥ 65 years.

ResultsWe identified 80 cases of MG, with a prevalence rate of 260 cases/1 000 000 population (95% CI, 202.7-316.4), rising to 517.9/1 000 000 population in those aged ≥ 65 (95% CI, 363.2-672.9). Cumulative incidence in the study period was 15.4 cases per 1 000 000 person-years. Early onset (≤ 50 years) was recorded in 29.1% of cases.

ConclusionThe prevalence of MG in our health district is one of the highest published figures, and the disease is highly prevalent in the older population.

La miastenia gravis (MG) es un enfermedad autoinmune que afecta a la transmisión nerviosa a nivel de la unión neuromuscular causando debilidad muscular típicamente fluctuante. Los estudios epidemiológicos constatan un aumento de las tasas de prevalencia de la MG y es especialmente evidente en la población anciana.

ObjetivoRealizar un estudio epidemiológico retrospectivo para conocer las tasas de incidencia y prevalencia en la provincia de Ourense (Galicia) caracterizada por el envejecimiento poblacional.

Material y métodosLos pacientes fueron reclutados de nuestra base de datos clínica de enfermedades neuromusculares y a través de la búsqueda de pacientes con prescripción activa de bromuro de piridostigmina. La tasa de incidencia se estimó entre los años 2009-2018. Se estableció la fecha de prevalencia al 31/12/2018. El censo de la provincia de Ourense al 1/1/2019 era de 307.651 habitantes, de los que 96.544 (31.4%) tenían una edad ≥ de 65 años.

ResultadosSe identificaron 80 casos de MG. La prevalencia fue de 260 casos/1.000.000 habitantes (IC95%: 202.7-316.4), y en la población ≥ 65 años de 517.9/1.000.000 habitantes (IC95%: 363.2-672.9). La incidencia acumulada en el periodo de estudio fue de 15.4 casos/1.000.000 habitantes-año. El inicio precoz (≤ 50 años) ocurrió en el 29.1% de los casos.

ConclusiónLa prevalencia de la MG en nuestra área sanitaria es de las más altas entre las cifras previamente reportadas, y es una enfermedad muy prevalente en la población anciana.

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease in which several antibodies, especially those targeting acetylcholine receptors (AChR) located on the postsynaptic membrane in the neuromuscular junction, are responsible for the characteristic symptoms of fluctuating muscle weakness. Despite the high rate of positivity for these antibodies, up to 85% in generalised MG, they go undetected in some cases, which are classified as seronegative MG; these patients may present other antibodies, mainly those targeting muscle specific-kinase (MuSK) and low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein 4 (LRP4). The characteristic clinical symptoms may be ocular (ptosis, diplopia), bulbar (dysarthria, dysphagia), or generalised (limb weakness). Symptom exacerbation, known as myasthenic crisis, may lead to respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. In electrophysiological studies, this weakness may present as a decrement of compound muscle action potentials with repetitive nerve stimulation. Symptomatic treatment includes pyridostigmine and disease-modifying drugs, that is, immunosuppressant drugs including prednisone, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil.1,2

MG may manifest at any age. Epidemiological studies have consistently reported a bimodal incidence pattern in women, with one peak between the ages of 20 and 40 years and another between the ages of 60 and 80 years, whereas in men it predominantly appears in advanced age, with a sustained increase from the age of 60 years.3 This bimodal distribution among women has not been observed in the Korean population, in which both sexes present continuously increasing prevalence up to the age of 80 years.4

Epidemiological studies have also reported an increase in MG incidence and prevalence rates in the last decades,5–8 and more surprisingly an increase in its prevalence among the elderly population.9–12 This has also been observed with patient selection through the use of clinical databases, positive laboratory results for anti-AchR antibodies,13,14 and pharmacy records on the use of pyridostigmine.15

According to the results of epidemiological studies, we may conclude that the prevalence of MG is increasing in the elderly population, and that the disease is very probably clinically underdiagnosed due to the copresence of other conditions more frequent in this age group, such as cerebrovascular disease, or due to the assumption that such symptoms as weakness or fatigue are simply part of the ageing process. Regarding this point, Ourense is one of the provinces with the oldest populations in Spain, with 31% of the population being older than 65 years. The aim of this study is to determine the incidence and prevalence rates of MG in the province of Ourense, and to try to confirm the increased incidence reported by recent epidemiological studies.

Patients and methodsThe aim of our study is to calculate the prevalence of MG in the province of Ourense using a retrospective epidemiological study, taking 31 December 2018 as the prevalence date; we also estimated the incidence rate of MG for the period 2009-2018.

Patient data were gathered from the outpatient neurology clinics of the province of Ourense (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense, Hospital Comarcal de Verín, and Hospital Comarcal de O Barco de Valdeorras); we also contacted the province’s private clinics. The pharmacy department searched for all patients receiving pyridostigmine bromide (Mestinon®) and we crossed these results with those from the clinical database. Finally, we requested that the clinical records department gather hospital admission reports with a main or secondary diagnosis code of MG.

Definition of caseDiagnosis of MG was established in patients presenting compatible symptoms (fluctuating muscle weakness, whether ocular, bulbar, or generalised), and positive test results for anti-AchR or anti-MuSK antibodies and/or neurophysiological study results showing a > 10% decrement in compound muscle action potentials after repetitive nerve stimulation or prolonged jitter in the single-fibre electromyography. Patients were classified according to the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) clinical classification.16

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the region of Galicia. All patients gave written informed consent for us to access their medical data and perform the necessary serological tests.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistics software. We used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to check the normal distribution of variables (goodness of fit) and subsequently performed parametric (mean, standard deviation, t test) or non-parametric statistical tests (median, range, Mann-Whitney U test). Values of P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

ResultsAs of 1 January 2019, the number of registered inhabitants in the province of Ourense was 307 651. At the prevalence date (31 October 2018), 80 patients with MG were detected. The medical report of the eldest (92 years) mentioned diagnosis of MG and treatment with pyridostigmine, with no electronic or paper medical history; therefore, with the exception of the prevalence rate, the remaining variables were calculated using a population of 79 patients. Mean age (standard deviation) was 57 (18) years at diagnosis (median, 61 years; range, 20-85) and 68 (16) years at the prevalence date (median, 72 years; range, 30-92), with a progression time of 9.8 (9.2) years (median, 8 years; range, 1-50). Women accounted for 53.8% of patients.

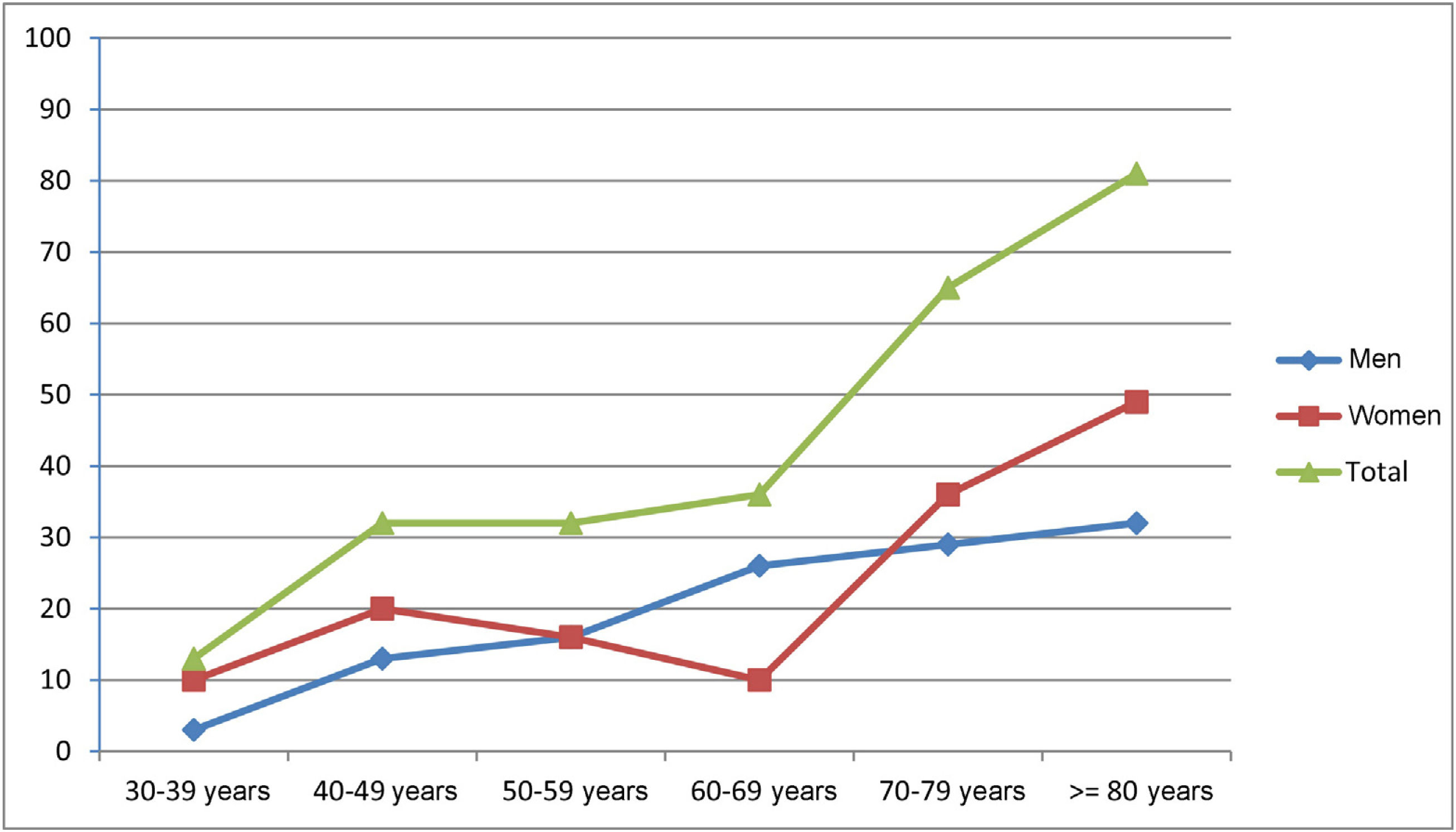

Prevalence was estimated at 260.0 cases per million population (95% CI, 202.7-316.4). Patients aged ≥ 65 years accounted for 62.5% of cases (n = 50). The registered number of inhabitants in this age group in the province of Ourense was 96 544 (31.4% of the total population); therefore, prevalence of MG in this group amounted to 517.9 cases per million population (95% CI, 363.2-672.9). Early-onset MG (< 50 years) was recorded in 29.1% of patients (n = 23) and late-onset MG (≥ 50 years) in 70.9% (n = 56). Early-onset MG was significantly more frequent among women (60.9%, vs 39.1% in men; P < .05). Table 1 and Fig. 1 show the global and sex-specific prevalence at the prevalence date.

During the study period between 2009 and 2018, 48 new cases of MG were recorded, which amounts to an annual incidence rate of 15.44 cases per million person-years (95% CI, 2.14-28.73).

The most frequent clinical manifestation was ocular MG (MGFA class I), in 57.7% of patients (n = 45), followed by MGFA class IIB, in 29.5% (n = 23), and MGFA class IIA, in 10.3% (n = 8). Therefore, in 92.5% of cases, MG type was purely ocular or mild generalised.

Serological tests detected anti-AchR antibodies in 79.7% of patients (n = 63), anti-MuSK antibodies in 3.8% (n = 3), and neither antibody in 16.5% of patients (n = 13).

Thymectomy was performed in 31.6% of cases (n = 25), and anatomical pathology studies revealed thymoma in 12 patients. One patient presenting radiological signs of thymoma in a chest CT scan did not undergo surgery due to medical comorbidities. The rate of MG associated with (paraneoplastic) thymoma was 16.5%.

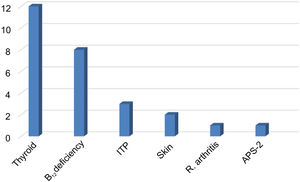

Vitamin D deficiencies (< 30 ng/mL) were recorded in 85.1% of patients, with a median of 17 ng/mL (range, 3-66 ng/mL). Comorbid autoimmune diseases were present in 35.4% of cases (n = 28), including 13 patients with thyroid disease (12 with hypothyroidism and one with Graves disease), 8 with vitamin B12 deficiency and chronic atrophic gastritis, 3 with autoimmune thrombocytopaenia, 2 with skin diseases (atopic dermatitis, vitiligo), one patient with rheumatoid arthritis, and one with autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2. Three patients with vitamin B12 deficiency presented concomitant hypothyroidism (n = 1) and thrombocytopaenia (n = 2) (Fig. 2).

Autoimmune comorbidities in patients with myasthenia gravis. The most frequent condition was thyroid disease. Vitamin B12 deficiency was associated with hypothyroidism in one patient and with ITP in 2 patients.

ITP: immune thrombocytopenic purpura; APS-2: autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2.

Only 2 patients were in complete remission. Pyridostigmine was used by 91.3% of patients. Seventy patients were receiving immunosuppressant treatment (87.5%), with 47 taking prednisone (13.2 [11.3] mg/day), 18 azathioprine, 4 mycophenolate mofetil, 2 rituximab, and one taking tacrolimus. Twenty-one patients (26.6%) were admitted to hospital due to myasthenic crises, receiving intravenous immunoglobulins as the first-line treatment, rather than plasmapheresis, with high-dosed intravenous corticosteroids.

DiscussionA 2010 systematic review of epidemiological studies on MG reports an estimated pooled incidence rate of 5.3 cases per million person-years (95% CI, 4.4-6.1) and an estimated pooled prevalence rate of 77.7 cases per million population (95% CI, 64.0-94.3). It is therefore classified as a rare disease, as its prevalence is below 50 cases/100 000 population.3Table 2 summarises the incidence and prevalence rates of MG reported in different epidemiological studies.4,15,17–37

Prevalence and incidence rates of myasthenia gravis in several epidemiological studies.

| Author | Region | Year (period) | Population | Incidence (cases per million) | Prevalence (cases per million) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zieda et al.17 | Latvia | 2010-2014 | 2 041 885 | 9.7 | 113.8 |

| Lee et al.4 | Korea | 2010-2014 | 50 420 000 | 6.9 | 129.9 |

| Quintero-López et al.18 | Cuenca | 2014 | 105 | ||

| Santos et al.19 | Northern Portugal | 2013 | 3 689 682 | 6.3 | 111.7 |

| Aragonès et al.20 | Osona (Barcelona) | 2013 | 155 069 | 328.9 | |

| Breiner et al.21 (≥ 18 years) | Ontario (Canada) | 1996-2013 | 11 274 236 | 28 | 320 |

| Joensen22 | Faroe Islands (Denmark) | 1986-2013 | 48 101 | 9.4 | |

| Díaz Marín23 | Marina Baixa (Alicante) | 2012 | 198 233 | 186.6 | |

| Park et al.24 | Korea | 2010-2011 | 50 908 646 | 24.4 | 106.6 |

| Gattellari et al.15 | Australia | 2009 | 21 874 920 | 24.9 | 117.1 |

| Pallaver et al.25 | Trento (Italy) | 2005-2009 | 524 826 | 14.8 | 129.6 |

| Lai et al.26 | Taiwan | 2007 | 22 960 000 | 21 | 140 |

| Heldal et al.27 | Norway | 1995-2007 | 4 737 171 | 7.0 | |

| Casetta et al.28 | Ferrara (Italy) | 1985-2000 | 360 950 | 20 | |

| Robertson et al.29 | Cambridgeshire (UK) | 1992-1997 | 684 000 | 15 | 111 |

| Poulas et al.30 | Greece | 1983-1997 | 10 475 878 | 7.4 | 70.63 |

| Villagra-Cocco et al.31 | La Palma (Canary Islands) | 1996 | 81 507 | 85.9 | |

| Cisneros et al.32 | Cuba | 1996 | 4.52 | 29.22 | |

| Christensen et al.33 | Western Denmark | 1975-1989 | 2 800 000 | 5.0 | 78 |

| Somnier et al.34 | Denmark | 1987 | 4.4 | 77 | |

| Ööpik et al.35 | Estonia | 1970-1986 | 1 462 130 | 4.0 | 99 |

| Philips et al.36 | Virginia (USA) | 1970-1984 | 555 851 | 9.1 | 142 |

| Storm-Mathisen et al.37 | Norway | 1951-1981 | 4.0 | 90 |

Epidemiological studies conducted in Spain are shown in italics.

Our study shows one of the highest MG prevalence rates reported to date. It also confirms that MG is more prevalent in older populations, with 518 cases per million population among individuals older than 65 years. This is also indirectly shown in late-onset MG, which affects 71% of patients; furthermore, the median age of patients with MG is 72 years. The incidence rate in the study period (15.44 cases per million person-years) is also among the highest reported, and the median progression time since diagnosis was 8 years, which means that over 50% of patients were diagnosed during that time period.

We observed no predominance in either sex, with women representing 54% of patients; we observed the typical pattern of bimodal incidence among female patients, with a discrete peak in the 40-49 age group and a sustained increase from the age of 70 years. We only observed predominance in women in the group of patients with early-onset MG. In men, we observed an age-dependent increase, which became more evident after the age of 50.

At the national level, we have found 4 studies on the epidemiology of MG in Spain. We should underscore the study by Aragonés et al.20 performed in the district of Osona (Barcelona), as it reports the highest prevalence rate, 329 cases per million population. The authors highlight that the study was performed in a very elderly population, with 16.87% of patients aged ≥ 65 in 2013, leading to a prevalence in this age group of 122.35 cases per 100 000 population (95% CI, 79.9-164.7), as compared to a prevalence of 21.87 cases per 100 000 population (95% CI, 12.03-31.70) in the 25-–64 age group. In general terms, our epidemiological data are similar, showing a prevalence rate of 260 cases per million population and clearly showing that MG is more prevalent in patients older than 65 years. However, given the older age of the population in our province, we expected to obtain an even higher prevalence rate in this age group, as the rate of 518 cases per million population obtained, though high, is considerably lower than that reported by Aragonés et al.20 Therefore, we should be aware of the fluctuating and non-specific symptoms in elderly patients, as MG may be underdiagnosed in our health district.

The remaining epidemiological studies were conducted in the island of La Palma (1996), finding a prevalence rate of 86 cases per million population,31 in the province of Cuenca (2014), with 105 cases per million population,18 and in Marina Baixa (Alicante, 2012), with 186.6 cases per million population.23

Among the international epidemiological studies, we would like to highlight the study by Santos et al.,19 conducted in northern Portugal, due to its geographical proximity and similar latitude/longitude coordinates. In a region with an estimated population in 2013 of 3 644 195, these authors reported an incidence rate of 63 cases per million person-years and a prevalence of 111.7 cases per million population. In women, incidence followed a bimodal pattern with one peak in the 15-49 age group and another in the ≥ 65 age group, whereas in men, both incidence and prevalence rates increased in all age groups. In women, prevalence was higher for early-onset MG (< 50 years) whereas among men, late-onset MG (≥ 50 years) was more prevalent.

Vitamin D has a modulatory effect on innate and adaptive immunity,38 and vitamin D deficiency has been reported in several autoimmune diseases, including MG.39 In our study, vitamin D deficiency was recorded in more than three-quarters of patients with MG. While this vitamin deficiency may be characterised as a pandemic, and occurs regardless of the latitude of a given region and therefore of the number of hours of sunlight and the amount of ultraviolet radiation reaching the skin, it is doubly important in patients with MG. On the one hand, the usual treatment includes long-term use of prednisone, which poses a risk for bone health as it favours osteoporosis and pathological fractures; on the other hand, vitamin D deficiency may lead to a proinflammatory environment that facilitates perpetuation of the autoimmune cascade.40 Therefore, the use of vitamin D supplements in patients with plasma levels below 30 ng/mL seems a good clinical option. Although fatigue in MG improves with vitamin D supplementation, in patients with vitamin D deficiency,41 research is needed to establish whether restoring vitamin D levels has an impact on disease progression. In this regard, treatment with denosumab is reported to be associated with clinical improvement and a decrease in plasma anti-AchR antibody titres,42 and remission of refractory MG has been reported in patients receiving megadoses of vitamin D.43

Autoimmune comorbidities were recorded in 28 cases (35.4%), with a clear predominance of thyroid disease, followed by vitamin B12 deficiency and presence of anti-gastric parietal cell antibodies. Previous studies have reported autoimmune diseases associated with MG in 14%-23% of cases,44–46 with autoimmune thyroiditis being the most frequently reported. We found no association with systemic diseases or connective tissue involvement.

In summary, we present a retrospective epidemiological study on the prevalence of MG in the province of Ourense, revealing one of the highest rates reported to date of a disease that predominantly affects the elderly population and is associated with vitamin D deficiency.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: García Estévez DA, López Díaz LM, Pardo Parrado M, Pérez Lorenzo G, Sabbagh Casado NA, Ozaita Arteche G, et al. Epidemiología de la miastenia gravis en la provincia de Ourense (Galicia, noroeste de España). Neurología. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2020.06.011