Time continues to be a fundamental variable in reperfusion treatments for acute ischaemic stroke. Despite the recommendations made in clinical guidelines, only around one-third of these patients receive fibrinolysis within 60minutes. In this study, we describe our experience with the implementation of a specific protocol for patients with acute ischaemic stroke and evaluate its impact on door-to-needle times in our hospital.

MethodsMeasures were gradually implemented in late 2015 to shorten stroke management times and optimise the care provided to patients with acute ischaemic stroke; these measures included the creation of a specific on-call neurovascular care team. We compare stroke management times before (2013-2015) and after (2017-2019) the introduction of the protocol.

ResultsThe study includes 182 patients attended before implementation of the protocol and 249 attended after. Once all measures were in effect, the overall median door-to-needle time was 45minutes (vs 74 minutes before, a 39% reduction; P<.001), with 73.5% of patients treated within 60minutes (a 47% increase; P<.001). Median overall time to treatment (onset-to-needle time) was reduced by 20minutes (P<.001).

ConclusionsThe measures included in our protocol achieved a significant, sustained reduction in door-to-needle times, although there remains room for improvement. The mechanisms established for monitoring outcomes and for continuous improvement will enable further advances in this regard.

El tiempo sigue siendo una variable determinante para los tratamientos de reperfusión del ictus isquémico agudo. A pesar de las recomendaciones de las guías clínicas, solo alrededor de la tercera parte de los pacientes con ictus isquémico agudo son fibrinolizados en ≤ 60 min. El objetivo de este trabajo es describir nuestra experiencia implementando un protocolo específico de atención del ictus isquémico agudo y evaluar su impacto en nuestros tiempos puerta-aguja.

MétodosA finales del 2015, se implantaron gradualmente unas medidas diseñadas para acortar los tiempos de actuación y optimizar la atención del ictus isquémico agudo incluyendo una guardia específica de Neurovascular. Se compararon los tiempos de actuación antes (2013-2015) y después (2017-2019) de la introducción de este protocolo.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 182 pacientes antes y 249 después de la intervención. Cuando todas las medidas fueron introducidas, la mediana global de tiempo puerta-aguja fue de 45 min (previa 74min, 39% menos, p <0,001) con un 73,5% de pacientes tratados en ≤ 60 min (47% más que preintervención, p <0,001). El tiempo global al tratamiento (inicio síntoma-aguja) se redujo en 20 min de mediana (p <0,001).

ConclusionesLas medidas asociadas en nuestro protocolo han conseguido una disminución del tiempo puerta-aguja de forma significativa y sostenida, aunque todavía nos queda margen de mejora, la dinámica establecida de control de resultados y mejora continua hará posible seguir avanzando en este sentido.

Over the past few years, several advances have been made in the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke, including the implementation of mechanical thrombectomy and an increased therapeutic window for reperfusion treatments. However, the aphorism “time is brain” still applies, as time remains a determinant variable in outcomes. In the case of intravenous fibrinolysis (IF), every minute counts, with a number needed to treat of 4 to achieve functional independence at 3 months in patients treated within 1.5hours of symptom onset, vs 14 in those treated within 4.5hours of onset.1 In this sense, clinical guidelines recommend performing IF within 60minutes of the patient's arrival at hospital (door-to-needle time [DNT]).2 Despite these recommendations, only around a third of patients with acute ischaemic stroke are treated within this timeframe.3-6 Several recent studies have shown that implementing specific treatment protocols for acute ischaemic stroke has led to a significant improvement in DNTs, and consequently, in the 3-month functional prognosis of these patients.7-11

Following the publication of clinical trials that have reliably shown the benefits of endovascular treatment for acute ischaemic stroke, Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet (HUMS), a reference centre for the community of Aragon (Spain), decided to implement a series of measures as part of a protocol to optimise code stroke (CS) care, improve time to IF, and effectively implement endovascular treatment.

The aim of this study is to describe these measures and our experience in implementing them, and to assess their impact on CS management times.

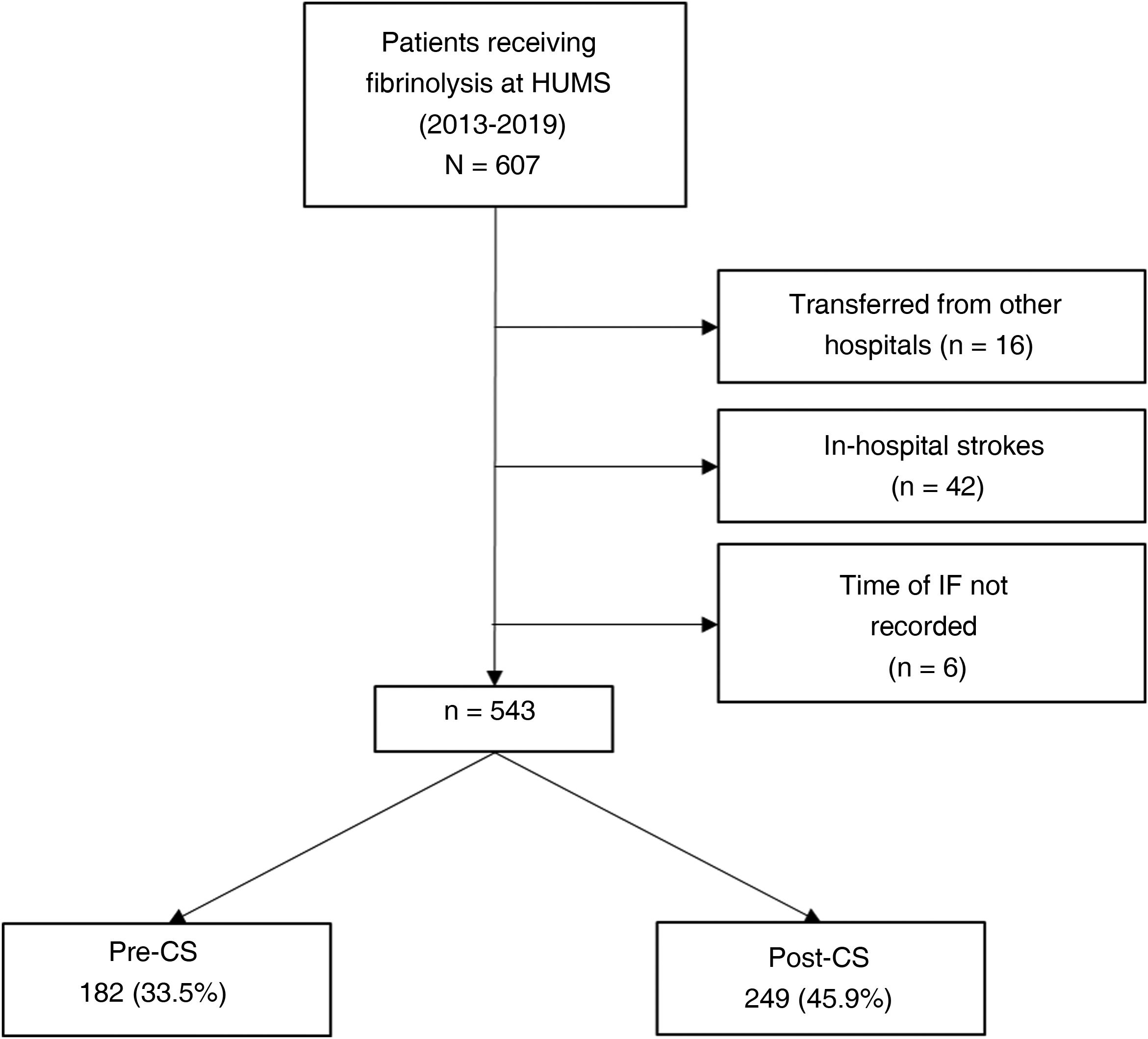

MethodsStudy design and populationThis is a non-controlled pre-post descriptive study that includes a period before (pre-CS period, from 1 January 2013 to 30 September 2015) and a period after the implementation of the protocol (post-CS period, from 1 March 2017 to 31 December 2019).

We included all patients with acute focal neurological signs arriving at the HUMS emergency department and treated with IF between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2019. We excluded patients transferred from another hospital or who were hospitalised at the time of acute ischaemic stroke, as in both cases care pathways are different and variable (eg, a brain CT scan may already have been performed in patients transferred from another hospital).

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the region of Aragon (project no. 18/2019).

InterventionThe intervention consisted in the implementation of a series of measures (Table 1) for CS care at HUMS between October 2015 and March 2017, when the last planned measure was implemented. This measure consisted in the creation of a unified on-call neurovascular service for Aragon, including a pool of neurologists from several hospitals in Aragon who work on-site at the HUMS until 21:00, and later on-call until 08:00 of the following day, and attend all CS patients arriving at our hospital, as well as providing endovascular treatment and telestroke care to patients from other hospitals in Aragon.

Comparison of measures and actions for code stroke care in the pre- and post-implementation periods.

| Measures/actions | Pre-CS | Post-CS |

|---|---|---|

| Population awareness | No scheduled activities are carried out. | Activities with patients’ associations every 6 months. Periodic campaigns promoting the recognition of warning signs and awareness of code stroke among the population and in the media |

| Training | No scheduled activities are carried out. | Regulated training of the pre-hospital, emergency department, and on-call staff |

| Creation of the on-call neurovascular service for Aragon | General neurologists attend code stroke and the remaining neurological emergencies. | CS patients are attended by neurologists from the on-call neurovascular service for Aragon. |

| Prenotification | Pre-hospital emergency services contact the hospital's emergency department; once the emergency physician has attended the patient, the on-call general neurologist is called and advised of the code stroke. | Pre-hospital emergency services directly call the on-call neurovascular neurologist to notify and activate CS. |

| Medical history | Patient's data and history are collected upon arrival at the emergency department. | As many details as possible are collected and a checklist of contraindications for IF is completed before the patient arrives at the emergency department. |

| Recording and request for brain CT scan | The brain CT scan is requested only after the patient has arrived at hospital and has been attended by the emergency physician. | Prenotification and CT room reservation. Data collection and request for a CT scan immediately after the patient's arrival, at the same time as the patient is assessed |

| Laboratory | Before IF, and at the emergency department, a blood analysis is performed, and a recombinant tissue plasminogen activator is administered while monitoring glycaemia levels; the INR is determined only in cases of known anticoagulation or suspected coagulation alteration. | No changes |

| IV line | IV line usually available upon patient's arrival, otherwise inserted in the emergency department | No changes |

| Directly to CT room | Upon arrival, the patient is transferred to an emergency department bed before being attended. | The patient is transferred in the ambulance stretcher to the CT room.a |

| IF in the CT bed | After the brain CT scan, the patient returns to the emergency room, where IF is indicated; preparation of the medication and doses to be administered begins. | The recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and necessary material to prepare and administer IF are brought to the CT bed (the agent is prepared and administered after the decision to administer IF is taken). |

CT: computed tomography; IF: intravenous fibrinolysis; INR: international normalised ratio; IV: intravenous; post-CS: post-implementation period; pre-CS: pre-implementation period.

From 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2019, we prospectively collected data on all fibrinolysis treatments performed at our centre: time of symptom onset (if known), time of arrival at the emergency department, time of brain CT scan, time of IF, and the intervals associated with those times: pre-hospital times (PHT, time from symptom onset to hospital arrival, when time of onset is known), door-to-CT time (DCT, time from arrival at hospital to brain CT scan), and DNT (time from the patient's arrival at hospital to administration of the IF bolus) and the onset-to-needle time (ONT, time from symptom onset to administration of the IF bolus). Baseline characteristics included age, sex, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score upon arrival at the emergency department, whether endovascular treatment was performed in addition to IF, how the patient arrived at the emergency department (by ambulance or by their own means), care during on-call hours, and whether the patient was attended on a working or non-working day.

Outcome variablesThe main outcome variable was the effect of CS implementation on DNT (median; percentage of treated patients with a DNT of 60minutes or less). As secondary variables, we determined the percentage of treated patients with a DNT of 45minutes or less, PHT, DCT, and ONT in the pre-CS and post-CS periods. We also aimed to determine the variables influencing the proportion of patients receiving fibrinolysis with DNTs of 60minutes or less.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were expressed as frequencies and quantitative variables as measures of central tendency (mean or median) and dispersion (standard deviation [SD] or interquartile range [Q1-Q3]). Normality of data was tested with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

For the inferential analysis, we used the chi-square test to compare proportions for qualitative variables, and the t-test or ANOVA to compare means when one of the variables was quantitative (Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed data).

Data were processed using the SPSS Statistics software (IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0.0.0; New York, NY, USA).

ResultsDuring the study period (January 2013-December 2019), 607 patients from our hospital received fibrinolysis; 543 met all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. Of these, 182 (33.5%) were treated in the pre-CS period, and 249 (45.9%) in the post-CS period (Fig. 1).

During the implementation of the CS protocol, the only measure that was not regularly fulfilled was “not transferring the patient from stretcher to bed and taking the patient directly to the brain CT scan.”

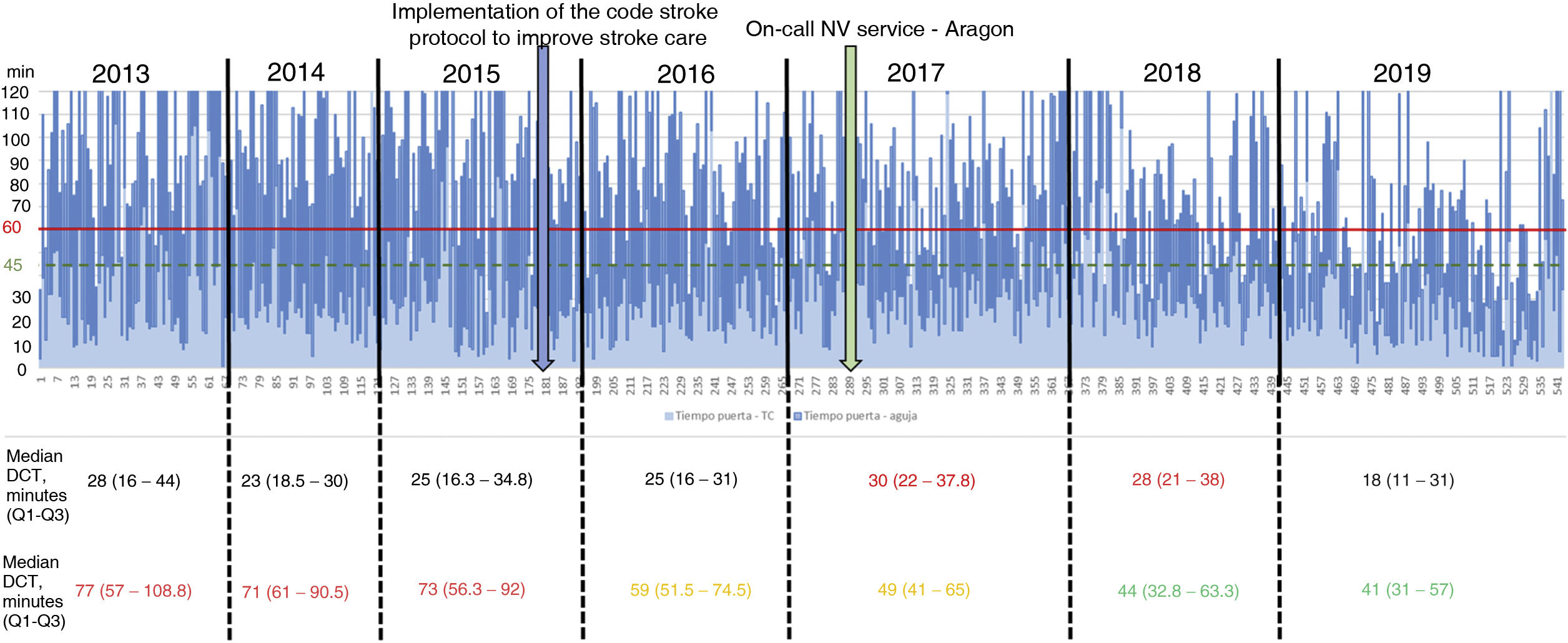

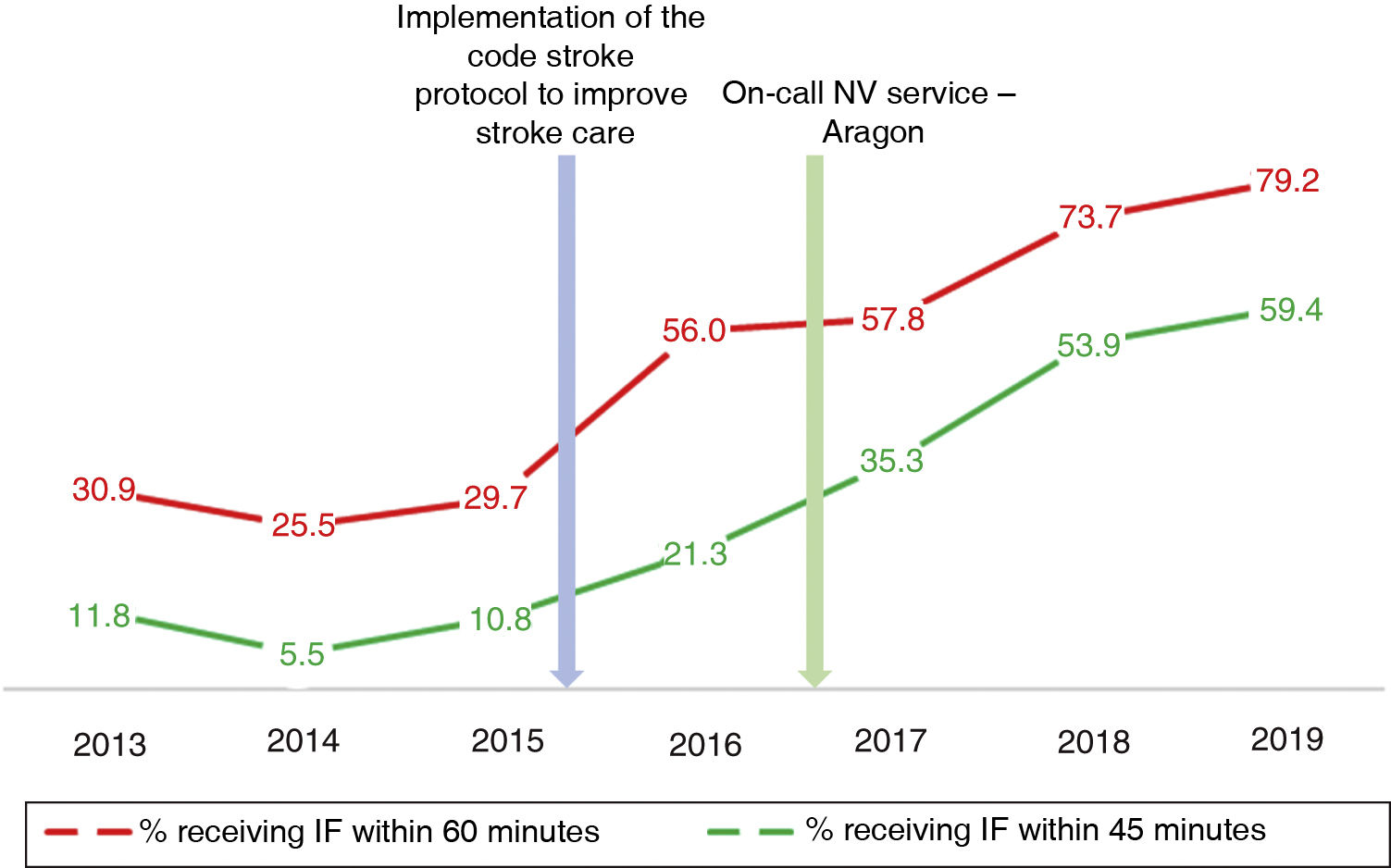

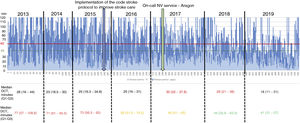

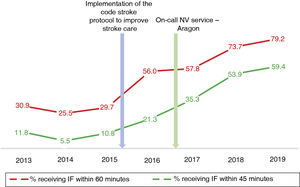

Table 2 describes the sample characteristics, with a higher proportion of patients undergoing thrombectomy (0.5% vs 32.1%, P < .001) and being transferred by ambulance (40.7% vs 67.9%, P < .001) during the post-CS period. Since the implementation of the CS protocol, there has been a progressive improvement in the median DNT per year, but not in the DCT (Fig. 2). The median DNT showed a statistically significant decrease (P < .001) from 74minutes (Q1-Q3, 59-97.3) in the pre-CS period to 45minutes in the post-CS period (Q1-Q3, 33-62.5); we also observed a significant improvement (P = .001) in the median ONT, from 155 (126.3-195) to 135 (94.3-190) minutes (Table 3). Furthermore, we observed a statistically significant increase in the proportion of patients receiving fibrinolysis within 60minutes of arrival at the emergency department (26.4% vs 73.5%, P < .001) and of patients with a DNT of 45minutes or less (8.8% vs 51.8%, P < .001) (Table 4). This progressive improvement in DNT was observed each year after the implementation of the CS protocol (Fig. 3). However, regarding ONT, we only observed a significant improvement in the proportion of patients receiving fibrinolysis within 90minutes of symptom onset (4.0% vs 23.2%, P < .001) (Table 4).

Baseline characteristics of our sample.

| Pre-CS | Post-CS | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 182 | n = 249 | ||

| Age in years, median (Q1-Q3) | 76.5 (68-84) | 79 (67.5-86) | .27 |

| > 80 years, n (%) | 65 (35.7) | 105 (42.2) | .17 |

| Men, n (%) | 96 (52.7) | 114 (45.8) | .15 |

| Non-working days, n (%) | 65 (35.7) | 74 (29.7) | .19 |

| Care during on-call hours, n (%) | 130 (71.4) | 181 (72.7) | .77 |

| Transferred by ambulance, n (%) | 74 (40.7) | 169 (67.9) | < .001 |

| NIHSS, median (Q1-Q3) | 11 (6-17) | 10 (6-16) | .18 |

| Mechanical thrombectomy, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 80 (32.1) | < .001 |

NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; post-CS: post-implementation period; pre-CS: pre-implementation period.

Comparative analysis of the different management times (expressed in minutes) before and after protocol implementation.

| Pre-CS | Post-CS | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median (Q1-Q3) | n | Median (Q1-Q3) | ||

| PHT | 176 | 75 (49-115) | 220 | 84 (52-138) | .033 |

| DCT | 182 | 24 (17-39) | 249 | 26 (16.5-35.5) | .842 |

| DNT | 182 | 74 (59-97.3) | 249 | 45 (33-62.5) | < .001 |

| ONT | 176 | 155 (126.3-195) | 220 | 135 (94.3-190) | .001 |

DCT: door-to-CT time; DNT: door-to-needle time; ONT: onset-to-needle time; PHT: pre-hospital time; post-CS: post-implementation period; pre-CS: pre-implementation period; Q1-Q3: interquartile range.

Comparative analysis of the proportion of patients receiving fibrinolysis in different time intervals.a

| Pre-CS (%) | Post-CS (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNT ≤ 60 min | 48 (26.4) | 183 (73.5) | < .001 |

| DNT ≤ 45 min | 16 (8.8) | 129 (51.8) | < .001 |

| ONT ≤ 180 min | 123 (69.9) | 160 (72.7) | .909 |

| ONT ≤ 90 min | 7 (4.0) | 51 (23.2) | < .001 |

DNT: door-to-needle time; ONT: onset-to-needle time; post-CS: post-implementation period; pre-CS: pre-implementation period.

Both in the pre-CS and the post-CS periods, the percentage of patients with a DNT of 60minutes or less was significantly higher among those transferred by pre-hospital emergency services than among patients arriving at the hospital by their own means (26 [35.1%] vs 22 [20.4%] in the pre-CS period and 136 [80.5%] vs 47 [58.8%] in the post-CS period). Receiving care on a working day was independently associated with DNT of 60minutes or less in the post-CS period only (77.1%) vs 48 (64.9%) (Table 5). In the pre-CS period, patients with a DNT of 60minutes or less presented higher median PHT (90 minutes [Q1-Q3, 55.3-103.4]) than those who received fibrinolysis with a DNT of more than 60minutes (73 minutes [Q1-Q3, 47.8-103.3], P = .016). This phenomenon, known as the “3-hour effect,” disappeared in the post-CS period (82.5minutes [Q1-Q3, 52-136.5] vs 85 minutes [Q1-Q3, 54.5-138.5], P = .906).

Factors associated with DNTs of 60minutes or less in the pre-CS and post-CS periods.

| DNT ≤ 60 min in pre-CS | DNT ≤ 60 min in post-CS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | P | |||

| Age in years, n (%) | ||||

| > 80 | 19 (29.2) | .514 | 78 (74.3) | .809 |

| ≤ 80 | 29 (24.8) | 105 (72.9) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Men | 22 (22.9) | .263 | 84 (73.7) | .95 |

| Women | 26 (30.2) | 99 (73.3) | ||

| Day of the week, n (%) | ||||

| Non-working days | 20 (30.8) | .316 | 48 (64.9) | .045 |

| Working days | 28 (23.9) | 135 (77.1) | ||

| Time of day, n (%) | ||||

| On-call hours | 36 (27.7) | .523 | 135 (74.6) | .524 |

| Office hours | 12 (23.1) | 48 (70.6) | ||

| Means of transport, n (%) | ||||

| Ambulance | 26 (35.1) | .026 | 136 (80.5) | < .001 |

| Own means | 22 (20.4) | 47 (58.8) | ||

| NIHSS score, n (%) | ||||

| ≤ 15 | 32 (24.8) | .454 | 129 (70.5) | .083 |

| ≥ 16 | 16 (30.2) | 53 (81.5) | ||

DNT: door-to-needle time; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; post-CS: post-implementation period; pre-CS: protocol pre-implementation period; post-CS: post-implementation period.

Statistically significant values are shown in bold.

In the treatment of ischaemic stroke, it is well known that “time is brain.” In line with this slogan, clinical guidelines recommend establishing DNT targets enabling us to monitor and improve the care of these patients. The recommendation that IF should be performed within the first 60minutes dates to 1995,12 since which time physicians have sought to treat the highest possible proportion of patients within this timeframe. In 2010, the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association launched the initiative “Target: Stroke” with the aim of achieving a DNT of 60minutes or less in at least 50% of patients receiving fibrinolysis.2 The project entered its second stage in 2014, with a target DNT of 60minutes or less in at least 75% of patients and, as a secondary objective, a DNT of 45minutes or less in at least 50% of patients receiving fibrinolysis.13 Similarly, the “Angels” initiative, launched in 2016, recommends optimising the quality of the reperfusion treatment at the centres attending acute ischaemic strokes, and promotes the adoption of several measures to shorten DNT and help meet these objectives.14

In our study, the median DNT significantly decreased from 74minutes (Q1-Q3, 59-97.3) in the pre-CS period to 45minutes (33-62.5) in the post-CS period. This sustained improvement started when the CS protocol began to be implemented in our centre, in late 2015, reaching 41minutes (Q1-Q3, 31-57) in 2019, with a constant and progressive increase year on year in the percentage of patients receiving fibrinolysis within 60 and 45minutes of arrival at the emergency department. In 2019, the objectives of the “Target: Stroke” initiative were met. This is consistent with the outcomes of similar studies, which describe their results after the implementation of a protocol aiming to improve the management times.7-11

This improved DNT led to shorter ONT (135minutes [Q1-Q3, 94.3-190] in the post-CS period vs 155minutes [Q1-Q3, 126.3-195] in the pre-CS period [P < .001]). Therefore, despite longer PHTs, the percentage of patients receiving IF within 1.5hours of symptom onset increased (23.2% vs 4.0%). This is the period associated with the lowest number needed to treat to obtain functional dependence with IF.1

Every update to the clinical guidelines includes the recommendation to establish action protocols to optimise DNT.15-17 However, implementing a CS action protocol is no easy task, as this is a multidisciplinary process. It requires adequate coordination and collaboration between all participants in the care process, including those intervening before the patient's arrival at hospital. The measures implemented by Meretoja et al.7 in Helsinki, which achieved DNTs of 20minutes or less in over 50% of patients, were progressively and systematically introduced over a period of approximately 13 years.7 Overall, the target DNT of 60minutes or less is only achieved in approximately one-third of patients receiving fibrinolysis.3-6 Even after implementation of the 10 recommendations of the “Target: Stroke” initiative in the USA, only 41.3% of patients received fibrinolysis with a DNT of 60minutes or less during the postintervention period.5 Subsequently, when assessing the outcomes after implementation of phase 2 of the initiative, the median DNT was 52.6minutes; the objective of achieving DNTs of 60minutes or less in at least 75% of patients was not met.13 More recently, the post-hoc analysis of DNTs in the Thrombolysis Implementation in Stroke (TIPS) study did not find significant differences between the proportions of patients receiving fibrinolysis with a DNT of 60minutes or less in the pre- and postintervention periods, with a final proportion of 30%,18 illustrating the difficulty of extrapolating the excellent results from a single hospital, in this case in Melbourne, to the rest of Australia.

Unlike the experience reported in the above-mentioned studies,7-11 we did not consider or were unable to implement some measures that may have helped to further decrease DNTs. For example, we were unable to consistently implement the direct transfer of the patient to the CT room after arrival at the hospital, which is considered fundamental in decreasing DNTs7,13; this is reflected in the limited change observed in DCTs over the study period (Fig. 2, Table 3). Despite the fundamental importance of this objective, it is not easy to achieve; in fact, it was one of the most frequently unmet measures in the analysis of the results after the implementation of phase 2 of the “Target: Stroke” initiative.13 We did not implement the recommendation to prepare the fibrinolytic agent before the patient's arrival at hospital in cases considered highly likely to receive fibrinolysis,7,13 due to the costs associated with unused vials. Another measure described in other studies that we did not implement was drawing blood after starting administration of the recombinant tissue plasminogen activator.7,8

The availability of an on-site on-call neurology service also enables shorter times to the administration of fibrinolytic treatment, as compared with an off-site on-call neurology service.19 In our case, the creation of the on-call neurovascular service for Aragon, a homogeneous group of neurologists trained in neurovascular care and receiving continuous training (meetings, monthly sessions, etc), though it is mainly dedicated to managing endovascular treatment, helped to improve DNTs (Figs. 2 and 3). It probably also played a role in the disappearance of the “3-hour effect” (whereby patients with shorter symptom progression times, and thus more time in which to receive IV thrombolysis, are treated with less urgency)11 observed in the pre-CS period. Interestingly, management times were longer on non-working days, which led to the decision to replace the off-site neurovascular service with an on-site service, even during weekends, beginning in January 2019.

As in every process, some elements are more difficult to address. For instance, when patients arrive at the emergency department by their own means, prenotification to the on-call service is omitted; therefore, any programme seeking to shorten in-hospital management times for acute ischaemic stroke must inform the population not only about the symptoms of stroke but also raise awareness of the importance of using pre-hospital emergency services to arrive at the hospital. In our study, the proportion of patients transferred to the emergency department by ambulance increased from 40.7% in the pre-CS period to 67.9% in the post-CS period (P < .001). Although the decrease in DNT in our study was independent of the means of transportation to the hospital, the proportion of patients with a DNT of 60minutes or less was much higher in those transferred by pre-hospital emergency services (35.1% vs 20.4% in the pre-CS period and 80.5% vs 58.8% in the post-CS period), confirming the importance of medical transport for in-hospital management times.

We also consider it important to mention the great importance of continuous training and periodic efforts to motivate the multidisciplinary team participating in the acute phase of CS, not only during implementation but also to maintain the improvements made; this has also been reported in other Spanish centres.11,20

Finally, the well-understood impact of time on the functional prognosis of patients with ischaemic stroke treated with IF leads us to set increasingly challenging objectives in DNT. Recent studies suggest that DNT targets should be reduced from 60 to 30minutes,21,22 but only a few studies implementing such ultra-rapid protocols in Spain have been published.11 This year, the “Target: Stroke” initiative has entered its third phase, with the objective of achieving DNTs of 60minutes or less in at least 85% of treated patients, 45minutes or less in 75% of patients, and 30minutes or less in at least 50% of patients.23 In conclusion, improving DNTs must be a constant, organised, and dynamic process at all hospitals treating acute ischaemic strokes, and there is no “floor” time that would permit us to relax.

Our study presents several limitations. Its design (non-controlled, pre-post study) may lead to a possible overestimation of the benefits of the intervention analysed; to minimise this bias, we aimed to determine baseline characteristics and the presence of other factors that may have contributed to the decrease in DNT in order to ensure a symmetrical distribution between the pre-CS and post-CS groups and, in the event of an asymmetrical distribution, to adjust the comparison model accordingly. We did not analyse the impact of the intervention on 3-month functional prognosis or on the post-IF haemorrhagic complications. However, previous studies have shown that early administration of IF in patients with acute ischaemic stroke is associated with better functional prognoses; therefore, we may assume that this benefit would be maintained in our sample.1 It is difficult to determine which measure played the greatest role in decreasing DNT. Although the interventions were initially planned simultaneously, their implementation was staggered, and records were not kept of the precise moment when each was finally implemented and the next was launched, with the exception of the last measure, the creation of the unified on-call neurovascular service for Aragon.

ConclusionWith the implementation of the measures associated with our protocol, we achieved a significant, sustained decrease in DNT and an increased proportion of patients receiving fibrinolysis within 60minutes or less. Furthermore, outcome control and continuous improvement dynamics have been established to continue advancing in this line.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.