Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS) is an infrequent condition characterised by a partial or total obstruction of blood flow through the superior vena cava due to extrinsic compression, infiltration, or thrombosis. Progression is variable and sometimes slow, and the condition can even be life-threatening; therefore, it requires a precise diagnosis and early treatment.1,2

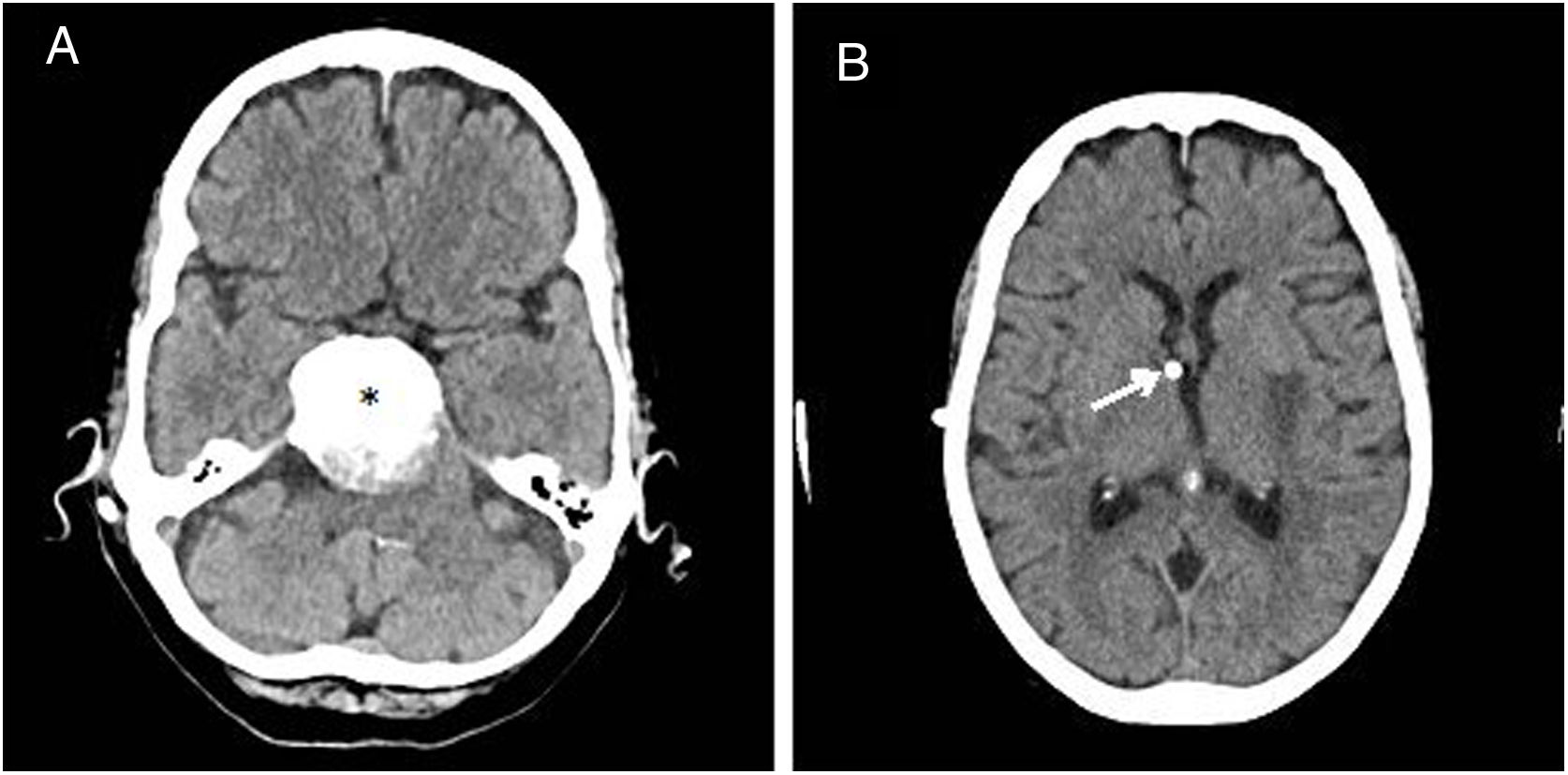

We present the case of an 82-year-old woman, who was partially dependent and was using a colostomy bag due to perforated diverticulitis. In 2013, she underwent radiosurgery for a petroclival meningioma measuring 4cm. She later developed non-communicating hydrocephalus due to external compression of the meningioma. As ventriculoperitoneal shunt was contraindicated due to the history of colostomy, she underwent ventriculoatrial shunt (VAS) implantation in December 2014 (Fig. 1).

In May 2019, the patient consulted our department due to global aphasia and right hemiparesis (muscle strength of 2/5), with onset upon waking. Given suspicion of stroke, we performed a multimodal CT scan, which revealed distal occlusion of the M1 segment of the left middle cerebral artery and favourable mismatch. The patient underwent mechanical thrombectomy, with angiography showing complete reperfusion. Despite this, neurological symptoms improved only slightly. A follow-up CT scan performed 24hours after the procedure revealed an ischaemic lesion involving the left lentiform nucleus and insula.

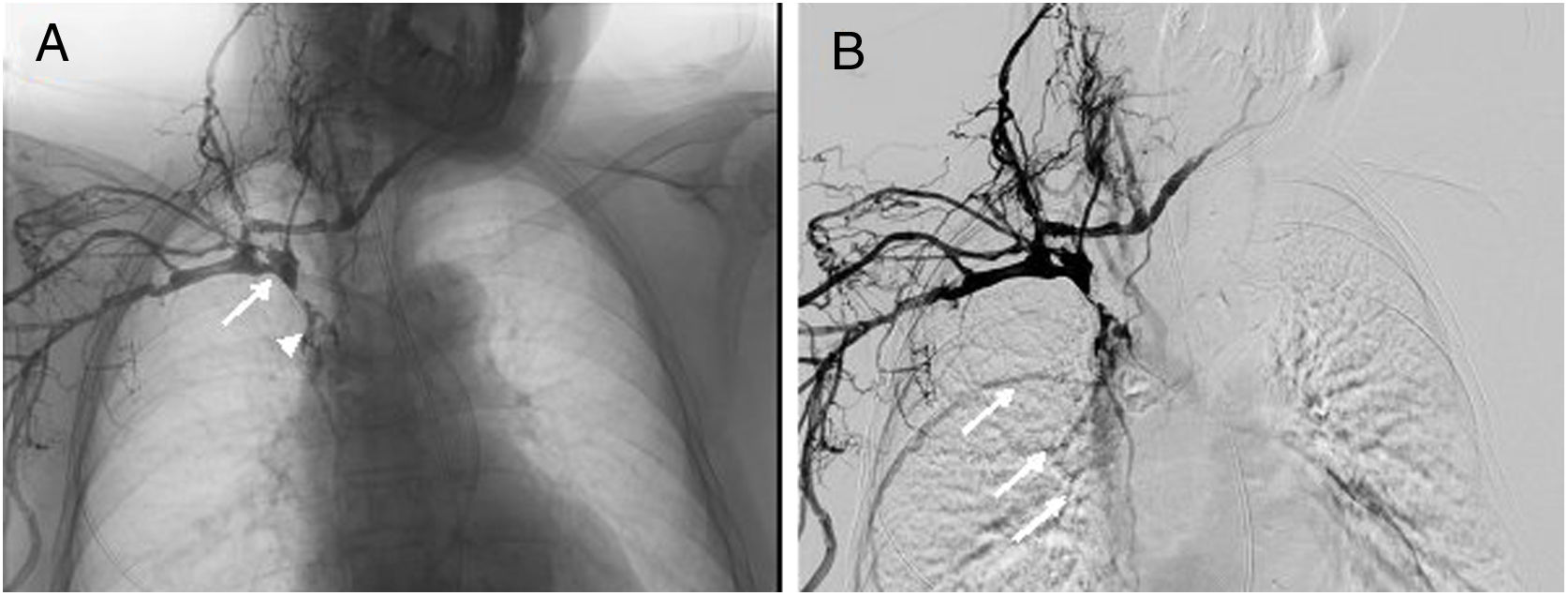

During her stay at the stroke unit, the patient presented oedema in the right arm, hindering the insertion of peripheral venous catheters. On the fifth day after admission, we also observed oedema in the face and contralateral arm; examination of the upper limbs yielded normal results. Given the suspicion of SVCS, we performed a Doppler ultrasound of the supra-aortic trunks, which revealed thrombosis of the internal jugular veins. We also requested a non-contrast chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT scan, which initially ruled out extrinsic venous compression or tumour and detected a displacement of the distal end of the VAS in the superior vena cava. A venography of the right arm confirmed thrombosis of the right subclavian vein, the brachiocephalic trunk, and the superior vena cava, with the latter showing contrast passage to the right atrium (Fig. 2). The venous system of the contralateral arm could not be studied due to the inability to insert a peripheral catheter.

Venography showing contrast administration after catheterisation of the right cephalic vein. (A) Obstruction of the superior vena cava (arrow), with filiform passage of contrast to the right atrium (arrowhead); (B) collateral filling of thoracic wall veins towards the azygos vein (arrows).

After reassessing the patient's clinical situation, and having verified the correct functioning of the VAS, we opted for conservative treatment with enoxaparin at a therapeutic dose of 1mg/kg every 12hours. In the following weeks, we observed complete resolution of the facial oedema and partial resolution of the oedema in the arms.

Aetiological study of stroke included a transthoracic echocardiography without echo-enhancing agents, which yielded normal results, and a transcranial Doppler ultrasound right-to-left shunt test, which showed positive results, suggesting a paradoxical embolism from the superior vena cava thrombosis.

Global aphasia and right hemiparesis persisted. After clinical stability was achieved, the patient was discharged with prescription of anticoagulation therapy with warfarin at 32mg weekly, for an indefinite period of time.

SVCS is a complex clinical syndrome whose aetiology has changed over time. The most frequent cause is currently malignant mediastinal neoplasm, especially small-cell lung cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.3 However, the increasing use of semi-permanent intravascular (venous catheters, haemodialysis) and cardiac devices (pacemakers, defibrillators) has significantly contributed to the appearance of new cases, representing the first non-neoplastic cause of SVCS.4,5

Ventricular shunt is one of the most widely used neurosurgical procedures in the treatment of hydrocephalus. Over the past 20 years, ventriculoperitoneal shunts have preferentially been used due to the technical challenge and the cardiopulmonary and renal complications observed with VAS.6–8 However, no published study has reported cases of SVCS, as observed in our patient. We can only refer to the literature published in the 1960s on children undergoing VAS placement due to hydrocephalus of non-neoplastic origin.9–11 The postulated mechanism states that atrial contraction during the cardiac cycle favours retrograde transmission of the movement to the rest of the catheter, whereas proximal displacement promotes thrombosis due to reduced mobility of the distal end in the superior vena cava.12

Cardioembolic aetiology accounts for 25% of ischaemic strokes. Less frequent cardioembolic causes include patent foramen ovale, which is present in 25% of the general population and is diagnosed in up to 40% of younger patients with otherwise cryptogenic stroke.13

From a therapeutic point of view, endovascular procedures (local fibrinolysis, percutaneous angioplasty) constitute the first line of treatment for SVCS secondary to intravascular devices.14 The functional prognosis of our patient, the risk associated with invasive techniques, and the proper functioning of the VAS led us to opt for conservative treatment, achieving partial symptom resolution.

The interest of this case resides in its unusual form of presentation: ischaemic stroke secondary to paradoxical embolism, which has not previously been reported. In fact, a retrospective series of 70 patients with ischaemic stroke of infrequent aetiology reported no cases of this clinical manifestation.15

In conclusion, considering the possible development of SVCS, it is essential to continuously monitor patients with semi-permanent intravascular devices, as the complications may be catastrophic.

Please cite this article as: Molina-Gil J, Calleja-Puerta S, Rico M. Infarto cerebral por embolismo paradójico secundario a síndrome de vena cava superior por malposición de un catéter de derivación ventriculoauricular. Neurología. 2021;36:325–327.