The number of people diagnosed with dementia globally has dramatically increased in recent years. The objective of this study was to explore beliefs and knowledge among the Cuban population with regard to the risk factors that may lead to dementia and the actions that may be taken to prevent it.

MethodIn an exploratory cross-sectional study, we surveyed a total of 391 people aged between 18 and 96 years. The results were stratified by sex, age range, level of education, and contact with dementia.

ResultsDementia was the fourth most worrying disease. A total of 64.5% of participants believed that the risk of dementia could be reduced, and 60% that the appropriate time to begin prevention measures is after the age of 40. Cognitive stimulation and healthy diet were more frequently cited as useful activities to reduce risk. Survey respondents reported little presence in their lifestyle of behaviours that are beneficial for reducing the risk of dementia.

ConclusionsAlthough dementia is an important health issue for respondents, their knowledge about disease prevention is still insufficient. The results obtained constitute a starting point for the design of policies aimed at increasing knowledge about the disease and improving prevention.

El número de personas diagnosticadas con demencia a escala global se ha incrementado drásticamente en los últimos años. El propósito del presente estudio fue explorar las creencias y el conocimiento existente en la población cubana sobre los factores de riesgo que pueden conducir a la demencia y las acciones que pueden llevarse a cabo para su prevención.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio exploratorio transversal. Se encuestó a 391 personas, con un rango de edad entre los 18 y 96 años. Los resultados se estratificaron atendiendo a las variables sexo, rango de edad, escolaridad y contacto con demencia.

ResultadosLa demencia se ubicó como la cuarta enfermedad más preocupante para los participantes. El 64,5% consideró que el riesgo de demencia podía ser reducido y el 60% que la edad idónea para iniciar la prevención es posterior a los 40 años. La estimulación cognitiva y la dieta saludable fueron señaladas con más frecuencia como actividades útiles para reducir el riesgo, existiendo además poca presencia en el estilo de vida de los encuestados, de comportamientos que resultan beneficiosos para la reducción del riesgo de presentar demencia.

ConclusionesLa investigación constató que aunque la demencia constituye un tema de salud importante para los encuestados, todavía no se tiene suficiente conocimiento sobre las acciones a realizar para reducir el riesgo de presentarla. Los resultados obtenidos constituyen un punto de partida para el diseño de políticas dirigidas a potenciar el conocimiento sobre la demencia y su prevención.

According to the Pan American Health Organization, life expectancy in the Americas has increased by more than 20 years over the last half century. As a result, by 2020 the elderly population will comprise 200 million people, half of whom will live in Latin America and the Caribbean.1,2 In Cuba, life expectancy is over 77 years; 25% of the Cuban population is expected to be aged over 60 by 2020 (Cuba is the Latin American country with the highest percentage of elderly individuals).3 This has resulted in a significant increase in the number of elderly people diagnosed with dementia.4

Despite the traditional perception that these patients are on an irreversible path to cognitive decline, recent evidence suggests that dementia can actually be prevented.5 This requires the design and implementation of initiatives aimed at promoting cognitive health.6 Modifying the main risk factors for dementia (smoking, obesity, sedentary lifestyles, arterial hypertension, diabetes, and depression) may reduce the number of cases by up to 48.4%.7,8 Any initiative aimed at preventing dementia and promoting cognitive health should consider the target population's knowledge and beliefs about dementia6: misconceptions about brain and cognitive health, awareness of dementia risk factors, how to prevent cognitive impairment, etc. Several large studies conducted in developed countries have focused on these aspects, reporting interesting results. In Australia, a survey of 1003 individuals found that less than half of participants (41.5%) thought that the risk of dementia could be reduced. Furthermore, only 17.2% of individuals over the age of 60 and less than 6% of those younger than 60 considered dementia an important health issue.9 In a study conducted by the MetLife Foundation in the United States,10 74% of participants (n=1000) knew very little or nothing about dementia, especially Alzheimer disease (AD), whereas most elderly participants had heard about the disease but did not know how to prevent it.11 Recent studies have shown a lack of understanding about dementia prevention among healthcare professionals. A survey taken by 234 Australian healthcare professionals showed poor understanding of dementia, particularly regarding risk factors, prevalent disease types, and cognitive symptoms.12 However, most of these studies have focused on developed countries, whereas it is developing countries that currently present the highest rates of dementia and where rates are projected to increase the most in the near future.13

In Latin America and the Caribbean, very few studies have explored knowledge about dementia risk factors and prevention strategies. An extensive literature search yielded a single study conducted in Argentina, evaluating public knowledge and perception of AD.14 In the study, 85% of participants adequately identified symptoms, 40% regarded AD as a terminal disease, and 50% believed that definitive diagnosis of the condition could be established with a diagnostic test. However, the survey did not explore public knowledge about risk factors for dementia or possible measures to prevent the disease.

Given this situation, there is a need for research into public knowledge of dementia risk factors and prevention in Latin America and the Caribbean. This information is essential to the planning, design, and implementation of strategies to prevent dementia.15 The purpose of this study was to explore public understanding and beliefs about dementia risk factors and preventive strategies among the Cuban population.

Material and methodsParticipantsOur exploratory, cross-sectional study included data from a survey of 391 individuals: 223 women (57%) and 168 men (43%). Mean age was 41 years (range, 18–96). Participants were recruited in bus station waiting rooms, parks, coffee shops, and other public places. Interviewers explained the purpose of the study to all potential participants; only those individuals agreeing to participate completed the survey. The survey was conducted between January and July 2017, and took a mean of 15minutes per participant to complete.

MaterialsOur survey was based on the 6-item tool developed by Smith et al.9 Question 1 gathers general information about the respondent (age, sex, level of schooling, contact with patients diagnosed with dementia, etc.). Question 2 explores personal health concerns.

Question 3 asks whether the respondent believes that the risk of dementia can be reduced. This question has 5 response options, ranging from “it cannot be reduced” to “it can be reduced.” Question 4 enquires about the respondent's knowledge of actions that could reduce the risk of dementia. This question is open-ended in order to evaluate participants’ actual knowledge without introducing response bias.

Question 5 explores the participant's beliefs about activities they perform that may reduce the risk of dementia; this question is also open-ended. Question 6 enquires about the age at which preventive measures should be taken, in the respondent's opinion. Responses are classified by age group. Some of our questions have been used in other surveys.16,17

Statistical analysisWe analysed frequencies by calculating percentages for each age group. Responses to question 2 were classified by age group (≤27 years, 28–47 years, and ≥48 years). Responses to questions 3, 4, and 5 were classified by sex, age group (≤27 years, 28–47 years, and ≥48 years), level of schooling (primary education, secondary education, post-secondary education, and university studies), and contact with patients with dementia (yes/no). Data were analysed with the SPSS statistics software, version 21.0.

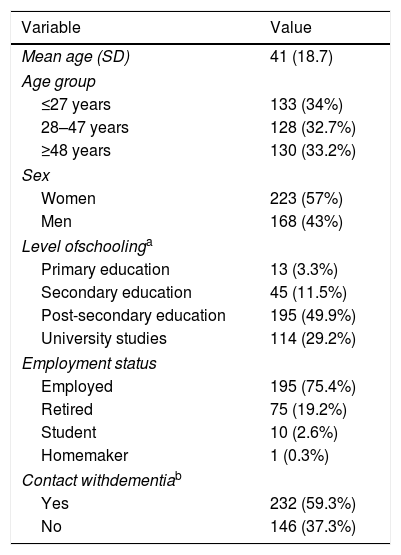

ResultsParticipant characteristicsParticipant characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Mean age (SD) was 41 (18.7) years; the group of respondents aged ≤27 years was slightly larger (34% of the sample). Our sample included more women than men (57%). Nearly half of the participants had completed post-secondary education, and most were in active employment (75.4%). Over half of our sample (59.3%) had some contact with people with dementia (relatives, neighbours, friends, etc.).

Characteristics of our sample.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 41 (18.7) |

| Age group | |

| ≤27 years | 133 (34%) |

| 28–47 years | 128 (32.7%) |

| ≥48 years | 130 (33.2%) |

| Sex | |

| Women | 223 (57%) |

| Men | 168 (43%) |

| Level ofschoolinga | |

| Primary education | 13 (3.3%) |

| Secondary education | 45 (11.5%) |

| Post-secondary education | 195 (49.9%) |

| University studies | 114 (29.2%) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 195 (75.4%) |

| Retired | 75 (19.2%) |

| Student | 10 (2.6%) |

| Homemaker | 1 (0.3%) |

| Contact withdementiab | |

| Yes | 232 (59.3%) |

| No | 146 (37.3%) |

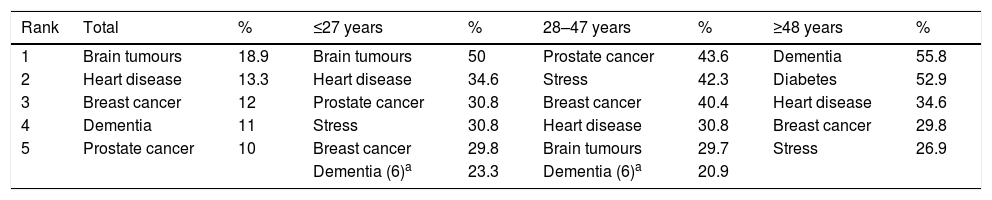

The most frequent health concerns, classified by age group, are shown in Table 2. Dementia was the greatest health concern for 11% of the sample and the fourth overall, after brain tumours, heart diseases, and breast cancer. Men were more frequently concerned about the risk of dementia than women. By age group, dementia was the greatest health concern (before diabetes, heart diseases, breast cancer, and stress) for 55.8% of individuals aged ≥48 years, 20.9% of those aged 28-47 years, and 23.3% of those aged ≤27 years; the condition ranked sixth among the most common health concerns of individuals in the 2 younger age groups.

The most frequent health concerns in our sample, by age group.

| Rank | Total | % | ≤27 years | % | 28–47 years | % | ≥48 years | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brain tumours | 18.9 | Brain tumours | 50 | Prostate cancer | 43.6 | Dementia | 55.8 |

| 2 | Heart disease | 13.3 | Heart disease | 34.6 | Stress | 42.3 | Diabetes | 52.9 |

| 3 | Breast cancer | 12 | Prostate cancer | 30.8 | Breast cancer | 40.4 | Heart disease | 34.6 |

| 4 | Dementia | 11 | Stress | 30.8 | Heart disease | 30.8 | Breast cancer | 29.8 |

| 5 | Prostate cancer | 10 | Breast cancer | 29.8 | Brain tumours | 29.7 | Stress | 26.9 |

| Dementia (6)a | 23.3 | Dementia (6)a | 20.9 |

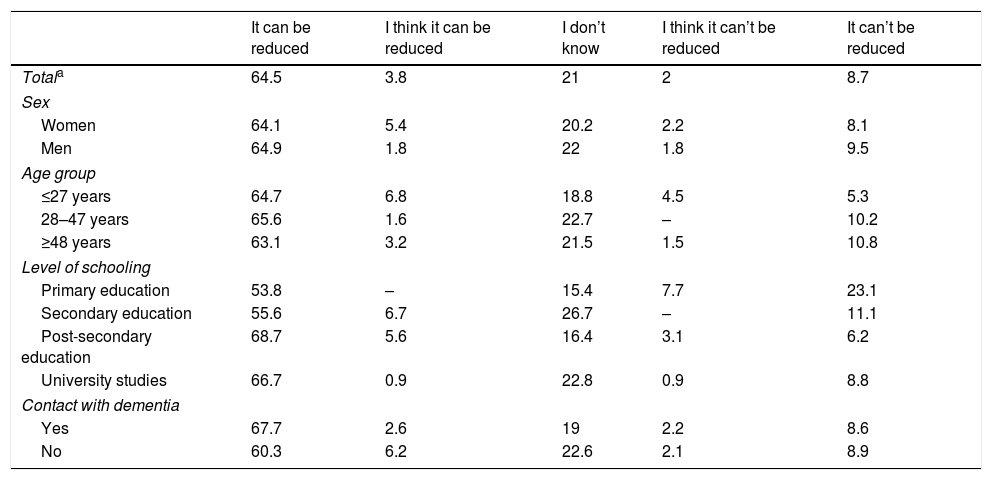

Table 3 summarises participants’ beliefs about the possibility of reducing the risk of dementia. Some 64.5% of participants responded that they were convinced that the risk of dementia could be reduced, 3.8% that they thought that it could be reduced, and 21% that they did not know. Men and women gave similar responses to this question (64.1% of men and 64.9% of women were convinced that the risk of dementia could be reduced). In all age groups, over 60% of participants were convinced that the risk of dementia could be reduced.

Beliefs about the possibility of reducing the risk of dementia in our sample.

| It can be reduced | I think it can be reduced | I don’t know | I think it can’t be reduced | It can’t be reduced | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totala | 64.5 | 3.8 | 21 | 2 | 8.7 |

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 64.1 | 5.4 | 20.2 | 2.2 | 8.1 |

| Men | 64.9 | 1.8 | 22 | 1.8 | 9.5 |

| Age group | |||||

| ≤27 years | 64.7 | 6.8 | 18.8 | 4.5 | 5.3 |

| 28–47 years | 65.6 | 1.6 | 22.7 | – | 10.2 |

| ≥48 years | 63.1 | 3.2 | 21.5 | 1.5 | 10.8 |

| Level of schooling | |||||

| Primary education | 53.8 | – | 15.4 | 7.7 | 23.1 |

| Secondary education | 55.6 | 6.7 | 26.7 | – | 11.1 |

| Post-secondary education | 68.7 | 5.6 | 16.4 | 3.1 | 6.2 |

| University studies | 66.7 | 0.9 | 22.8 | 0.9 | 8.8 |

| Contact with dementia | |||||

| Yes | 67.7 | 2.6 | 19 | 2.2 | 8.6 |

| No | 60.3 | 6.2 | 22.6 | 2.1 | 8.9 |

More than half of respondents were convinced that the risk of dementia could be reduced, regardless of the level of schooling (primary education, 53.8%; secondary education, 55.6%; post-secondary education, 68.7%; and university studies, 66.7%). Individuals with secondary education or university studies more frequently stated that they did not know whether it was possible to reduce the risk of dementia (26.7% and 22.8%, respectively). Some 23.1% of individuals with primary education were convinced that it was not possible. Most respondents were convinced that dementia risk could be reduced, regardless of whether or not they had contact with people with dementia (67.7% and 60.3%, respectively); 22.6% of participants who had no contact with people with dementia did not know whether the risk could be reduced.

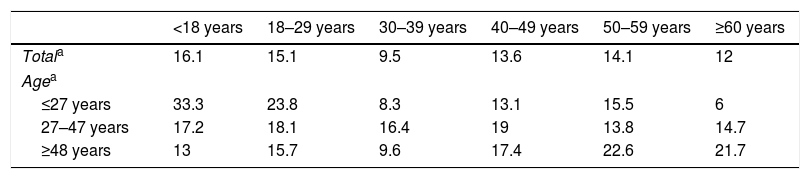

Regarding the optimal age to start taking preventive measures (Table 4), over half of participants aged ≤27 years believed that prevention should start before the age of 29, whereas 61.7% of individuals ≥48 years of age believed that prevention should start after the age of 40. Strikingly, 21% of respondents aged ≥48 years believed that prevention should start after the age of 60.

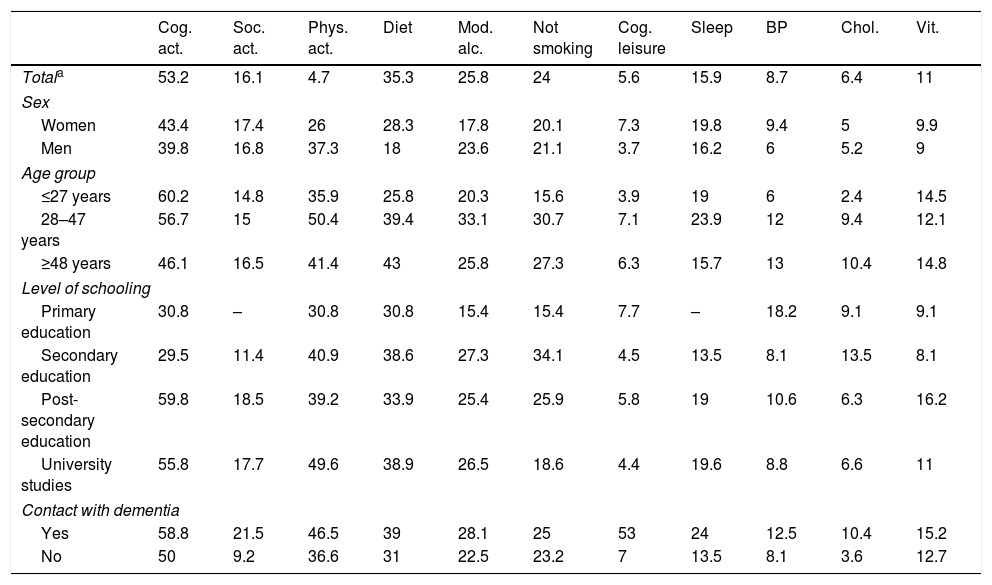

Table 5 lists the measures reported by our sample for reducing dementia risk. The measures most frequently reported were cognitive activities (e.g., stimulation exercises for attention, memory, reasoning, etc.; 53.2%), healthy diet (35.3%), moderate alcohol intake (25.8%), and not smoking (24%). Very few participants mentioned such measures as controlling arterial blood pressure (8.7%), reducing cholesterol levels (6.4%), performing cognitively stimulating leisure activities (e.g., solving crosswords, playing chess, learning a new language, etc.; 5.6%), or physical activity (4.7%).

Knowledge about activities and habits that may help prevent dementia.

| Cog. act. | Soc. act. | Phys. act. | Diet | Mod. alc. | Not smoking | Cog. leisure | Sleep | BP | Chol. | Vit. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totala | 53.2 | 16.1 | 4.7 | 35.3 | 25.8 | 24 | 5.6 | 15.9 | 8.7 | 6.4 | 11 |

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Women | 43.4 | 17.4 | 26 | 28.3 | 17.8 | 20.1 | 7.3 | 19.8 | 9.4 | 5 | 9.9 |

| Men | 39.8 | 16.8 | 37.3 | 18 | 23.6 | 21.1 | 3.7 | 16.2 | 6 | 5.2 | 9 |

| Age group | |||||||||||

| ≤27 years | 60.2 | 14.8 | 35.9 | 25.8 | 20.3 | 15.6 | 3.9 | 19 | 6 | 2.4 | 14.5 |

| 28–47 years | 56.7 | 15 | 50.4 | 39.4 | 33.1 | 30.7 | 7.1 | 23.9 | 12 | 9.4 | 12.1 |

| ≥48 years | 46.1 | 16.5 | 41.4 | 43 | 25.8 | 27.3 | 6.3 | 15.7 | 13 | 10.4 | 14.8 |

| Level of schooling | |||||||||||

| Primary education | 30.8 | – | 30.8 | 30.8 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 7.7 | – | 18.2 | 9.1 | 9.1 |

| Secondary education | 29.5 | 11.4 | 40.9 | 38.6 | 27.3 | 34.1 | 4.5 | 13.5 | 8.1 | 13.5 | 8.1 |

| Post-secondary education | 59.8 | 18.5 | 39.2 | 33.9 | 25.4 | 25.9 | 5.8 | 19 | 10.6 | 6.3 | 16.2 |

| University studies | 55.8 | 17.7 | 49.6 | 38.9 | 26.5 | 18.6 | 4.4 | 19.6 | 8.8 | 6.6 | 11 |

| Contact with dementia | |||||||||||

| Yes | 58.8 | 21.5 | 46.5 | 39 | 28.1 | 25 | 53 | 24 | 12.5 | 10.4 | 15.2 |

| No | 50 | 9.2 | 36.6 | 31 | 22.5 | 23.2 | 7 | 13.5 | 8.1 | 3.6 | 12.7 |

BP: controlling blood pressure; chol.: controlling cholesterol level; Cog. act.: cognitive activities; cog. leisure: cognitively stimulating leisure activities; diet: healthy diet; mod. alc.: moderate alcohol intake; phys. act.: physical activity; sleep: good sleep quality; soc. act.: social activities; vit.: vitamin supplementation.

The measures most frequently mentioned by women were cognitive activities (43.4%), healthy diet (28.3%), and physical activity (26%); men most frequently mentioned cognitive activities (39.8%), physical activity (37.3%), and moderate alcohol intake (23.6%). Approximately 92% of women and 96% of men did not mention cognitively stimulating leisure activities as being beneficial for dementia risk reduction.

In all age groups, cognitive activities were mentioned by over 50% of participants, followed by physical activity and healthy diet. Moderate alcohol intake (33.1%), not smoking (30.7%), cognitively stimulating leisure activities (7.1%), and improving sleep quality (23.9%) were more frequently regarded as beneficial by participants aged 28-47 years. By level of schooling, cognitive activities were the measure most frequently mentioned by individuals with primary education, post-secondary education, and university studies, followed by physical activity and healthy diet. Over half of respondents recognised the benefits of cognitive activities, regardless of contact with people with dementia. Participants who reported contact with patients with dementia more frequently mentioned cognitively stimulating leisure activities, physical activity, and healthy diet than those who did not.

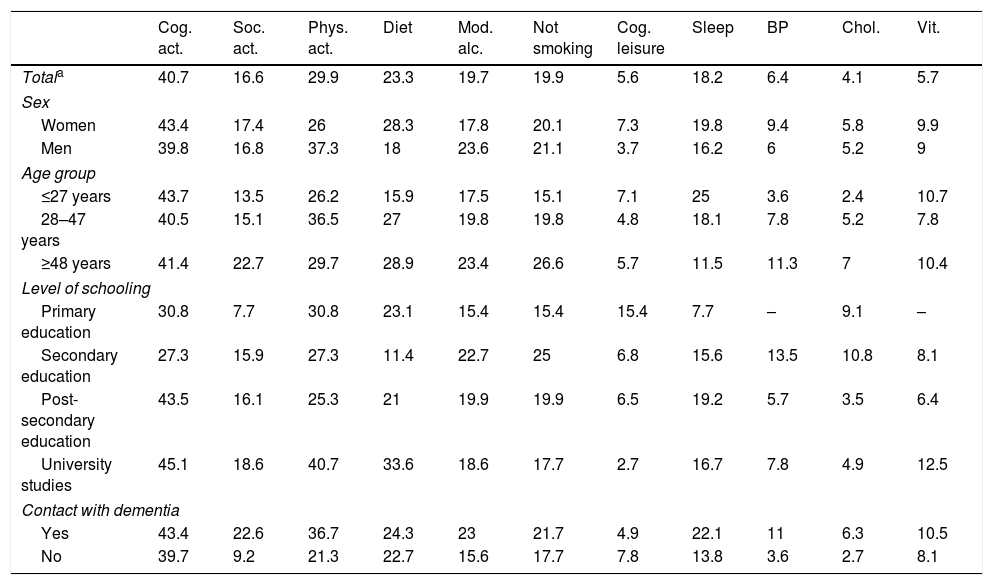

Table 6 lists the beneficial behaviours that survey respondents reported that they actually performed; the most frequent were cognitive activities (40.7%), physical activity (29.9%), and healthy diet (23.3%). Maintaining a low cholesterol level (4.1%), performing cognitively stimulating leisure activities (5.6%), and taking vitamins (5.7%) were rarely mentioned.

Preventive activities or habits performed by survey respondents.

| Cog. act. | Soc. act. | Phys. act. | Diet | Mod. alc. | Not smoking | Cog. leisure | Sleep | BP | Chol. | Vit. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totala | 40.7 | 16.6 | 29.9 | 23.3 | 19.7 | 19.9 | 5.6 | 18.2 | 6.4 | 4.1 | 5.7 |

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Women | 43.4 | 17.4 | 26 | 28.3 | 17.8 | 20.1 | 7.3 | 19.8 | 9.4 | 5.8 | 9.9 |

| Men | 39.8 | 16.8 | 37.3 | 18 | 23.6 | 21.1 | 3.7 | 16.2 | 6 | 5.2 | 9 |

| Age group | |||||||||||

| ≤27 years | 43.7 | 13.5 | 26.2 | 15.9 | 17.5 | 15.1 | 7.1 | 25 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 10.7 |

| 28–47 years | 40.5 | 15.1 | 36.5 | 27 | 19.8 | 19.8 | 4.8 | 18.1 | 7.8 | 5.2 | 7.8 |

| ≥48 years | 41.4 | 22.7 | 29.7 | 28.9 | 23.4 | 26.6 | 5.7 | 11.5 | 11.3 | 7 | 10.4 |

| Level of schooling | |||||||||||

| Primary education | 30.8 | 7.7 | 30.8 | 23.1 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 7.7 | – | 9.1 | – |

| Secondary education | 27.3 | 15.9 | 27.3 | 11.4 | 22.7 | 25 | 6.8 | 15.6 | 13.5 | 10.8 | 8.1 |

| Post-secondary education | 43.5 | 16.1 | 25.3 | 21 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 6.5 | 19.2 | 5.7 | 3.5 | 6.4 |

| University studies | 45.1 | 18.6 | 40.7 | 33.6 | 18.6 | 17.7 | 2.7 | 16.7 | 7.8 | 4.9 | 12.5 |

| Contact with dementia | |||||||||||

| Yes | 43.4 | 22.6 | 36.7 | 24.3 | 23 | 21.7 | 4.9 | 22.1 | 11 | 6.3 | 10.5 |

| No | 39.7 | 9.2 | 21.3 | 22.7 | 15.6 | 17.7 | 7.8 | 13.8 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 8.1 |

BP: controlling blood pressure; chol.: controlling cholesterol level; Cog. act.: cognitive activities; cog. leisure: cognitively stimulating leisure activities; diet: healthy diet; mod. alc.: moderate alcohol intake; phys. act.: physical activity; sleep: good sleep quality; soc. act.: social activities; vit.: vitamin supplementation.

The measures most frequently reported by women were cognitive activities (43.4%), healthy diet (28.3%), and physical activity (26%); men most frequently reported performing cognitive activities (39.8%), physical activity (37.3%), and consuming moderate quantities of alcohol (23.6%). The measure most frequently mentioned by survey respondents of any age was performing cognitive activities (≤27 years, 43.7%; 28–47 years, 40.5%; ≥48 years, 41.4%), followed by physical activity and healthy diet in the oldest 2 age groups. Good sleep quality was the third most frequent measure reported by participants aged ≤27 years. Individuals reporting contact with patients with dementia were more likely to perform activities beneficial for reducing the risk of dementia.

DiscussionMost common health concerns in the Cuban populationAccording to our results, most survey respondents did not regard dementia as a health priority; despite this, the condition was a more frequent health concern in our sample than in other studies.9,16 Dementia was the fourth most common health concern in our sample, with only 11% of participants reporting dementia as their main health concern. These results are consistent with those reported by Russo et al.18 in Argentina, where dementia is the third most frequent health concern, after cancer and cerebrovascular accidents. Contrary to other studies, men in our sample were more concerned about the risk of dementia than women (16% vs. 14%). For example, in the study by Smith et al.9 women were more concerned about developing dementia than men.

Furthermore, concern increased with age, with dementia becoming the main health concern for 55% of individuals older than 48 years, before heart disease, diabetes, and breast cancer. These age-related differences in the importance given to dementia have also been reported in studies conducted in the United States,10 Australia,9 France,19 and Israel.20 In our study, only 20.9% respondents aged 28 to 47 years were concerned about dementia; this percentage is even lower than that observed among participants aged ≤27 years (23.3%).

Beliefs about the possibility of reducing the risk of dementiaKnowing the public's beliefs about the possibility of reducing dementia risk is essential to the development of strategies aimed at raising awareness of the disease among the general population. Some 64.5% of survey respondents were convinced that the risk of dementia could be reduced, although 21% of participants did not know whether this was the case. Our results are consistent with those reported by other studies.

For example, in a study conducted in Australia, 72% of participants thought that the risk of dementia can be reduced21; 53% of individuals participating in a study conducted in the United States also believed this to be possible.10

Over 64% of our respondents were confident that the risk of dementia can be reduced, regardless of sex; in other studies, however, more men than women are convinced of this.9

By age group, 5.3% of participants aged ≤27 years, 10.2% of those aged 28-47 years, and 10.8% of those aged ≥48 years were convinced that the risk of dementia cannot be reduced. Over 50% of participants in all levels of schooling were convinced that the risk can be reduced. Most of the respondents who did not know if it was possible to reduce dementia risk had primary or university studies, whereas most participants who were confident that the risk of dementia could not be reduced had primary education only. Most of the participants who were convinced that dementia risk could not be reduced had no contact with people with dementia (22.6%).

These data must be interpreted with caution: contact with patients with dementia does not necessarily imply greater knowledge of the condition. Several surveys have revealed that even healthcare professionals (physicians and nurses) have poor knowledge of the risk factors and cognitive symptoms of dementia.12,22,23

These results may be due to differences in the terminology used in each survey. For example, “having contact with” a person with dementia is not the same as “being the caregiver of” one of these patients. The first term includes sporadic contact (neighbours, friends, colleagues, etc.), whereas the second refers to sustained contact requiring the caregiver to be trained in patient management and to be aware of specific information about the disease (acquired through medical appointments, the Internet, exposure to the course of the disease). When the survey uses the term “caregiver,” knowledge about the disease increases considerably.18,24

Another factor to consider is the perception about the optimal age for starting preventive measures. Over 27% of individuals aged ≤27 years established the optimal age before 29 years, whereas 61.7% of individuals aged ≥48 years stated that prevention should start after the age of 40. These findings are especially relevant in the light of evidence that the optimal age range for dementia prevention is 40-59 years.25,26 Providing accurate information about this factor may have a great impact on dementia risk reduction. In our sample, over 20% of participants aged 48 years and older stated that prevention should start after the age of 60; this belief may result in prevention starting too late.

Knowledge about activities beneficial for dementia risk reductionOver half of participants regarded cognitive activities as the most beneficial measure for reducing the risk of dementia, followed by healthy lifestyle (healthy diet, moderate alcohol intake, and not smoking). Future research should focus on the cognitive activities performed by these individuals. There is no conclusive evidence about the effectiveness of specific cognitive training for delaying age-related cognitive impairment.27–29 The idea may have become more popular with the development of computer programmes and applications that claim to act as “brain trainers,” improving cognitive performance. An example of this is the case of the well-known Lumosity brain training app, which in 2016 paid a $2 million fine over misleading advertising of its claimed effectiveness.27 Interestingly, women more frequently mentioned healthy diet, whereas men more frequently considered physical activity to be beneficial. According to some researchers, these differences may reflect differences in social constructs of gender and the impact they have on men's and women's beliefs.9

Preventive activities or habits performed by survey respondentsBroadly speaking, we observed discrepancies between what survey respondents knew to be beneficial for dementia risk reduction and what they actually did to reduce the risk. Only cognitive activities were performed by more than 40% of participants; most of these were individuals ≥48 years. Interestingly, only 30% of participants reported performing physical activity; 23% had a healthy diet; and 20% were non-smokers. Furthermore, very few individuals reported engaging in cognitively stimulating leisure activities, controlling blood pressure and cholesterol levels, or taking vitamin supplements. The effect of these measures on cognitive performance should be systematically evaluated.

According to some studies, a combination of physical activity and cognitive stimulation not only prevents dementia, but also improves cognitive performance in patients with advanced cognitive impairment.30 Sleep inadequacy is reported to be a predictor of dementia,6,31 whereas performing cognitively stimulating leisure activities reduces the risk of the disease.32 Several studies suggest that taking vitamin supplements (particularly vitamins B, C, D, and E) has neuroprotective effects, reducing the risk of dementia.33–35

According to our results, there may be a misconception among the Cuban population that dementia can be reliably prevented with a single preventive measure. However, current evidence suggests that modifying several risk factors is more effective in reducing the risk of dementia and slowing cognitive impairment.36

ConclusionsMounting evidence suggests that modifying certain risk factors and lifestyle habits may reduce the risk of dementia. Our study explored popular understanding and beliefs about dementia in a sample of the Cuban population.

In our sample, dementia was found to be the fourth most common health concern overall, and the first among those aged ≥48 years. Most survey respondents were convinced that the risk of dementia can be reduced, and 60% asserted that the optimal age for starting dementia prevention was older than 40years. Regarding the activities potentially beneficial for reducing the risk of dementia, our participants most frequently mentioned cognitive activities and healthy diet, but had limited knowledge of other preventive measures. Furthermore, survey respondents rarely practised the activities and habits known to be beneficial for dementia prevention.

Our results constitute a starting point for the development of policies aimed at raising awareness of dementia and its prevention, and provide useful data to determine the effectiveness of such interventions. Dementia should become a priority for healthcare systems, in the same way as such other diseases as arterial hypertension and diabetes.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Broche-Pérez Y, Fernández-Fleites Z, González B, Hernández Pérez MA, Salazar-Guerra YI. Conocimiento público y creencias sobre las demencias: un estudio preliminar en la población cubana. Neurología. 2021;36:361–368.