Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases constitute the leading cause of death in our setting. Stroke is the leading cause of disability and the second most frequent cause of death in adults. Over 90% of the burden of the disease is attributed to potentially preventable and modifiable risk factors, including short- and long-term exposure to air pollution.1–3 Multiple epidemiological studies conducted over the past decades have demonstrated the association between air pollution and vascular diseases, including stroke; as a result, air pollution is currently recognised as a well-established risk factor for vascular disease.4–7 However, we are unaware of whether this evidence is reflected in clinical practice guidelines for the management and prevention of vascular disease. Gaining a deeper knowledge of clinical recommendations for reducing the risk attributable to air pollution is of particular interest.

The aims of this review were as follows: (1) to analyse whether clinical practice guidelines for stroke prevention list air pollution as a risk factor for stroke, (2) to compare these data against recommendations from clinical practice guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease, and (3) to analyse the recommendations made to physicians on this issue.

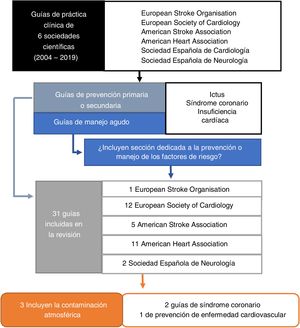

MethodsWe searched the PubMed database and the official websites of different scientific societies to gather clinical practice guidelines issued by 6 European and American organisations of reference in this topic: the European Stroke Organisation (ESO), the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), the American Stroke Association (ASA), the American Heart Association (AHA), the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC, for its Spanish initials), and the Spanish Society of Neurology (SEN, for its Spanish initials).

We included clinical practice guidelines meeting the following criteria (Fig. 1): (1) guidelines for primary and secondary prevention of stroke (ischaemic and haemorrhagic), heart failure, and coronary syndrome; and (2) acute management guidelines, provided that they included a section on the management of risk factors. We searched for guidelines issued between January 2004 (when air pollution was first recognised as a risk factor by a scientific society8) and December 2019.

ResultsA total of 31 clinical practice guidelines met the inclusion criteria (7 for stroke, 15 for heart failure or acute coronary syndrome, and 9 for cardiovascular disease prevention).

Three clinical practice guidelines (9%) listed air pollution as a risk factor (AHA, 2012; ESC-ESO, 2016; ESC, 2019) (Fig. 1).9–11

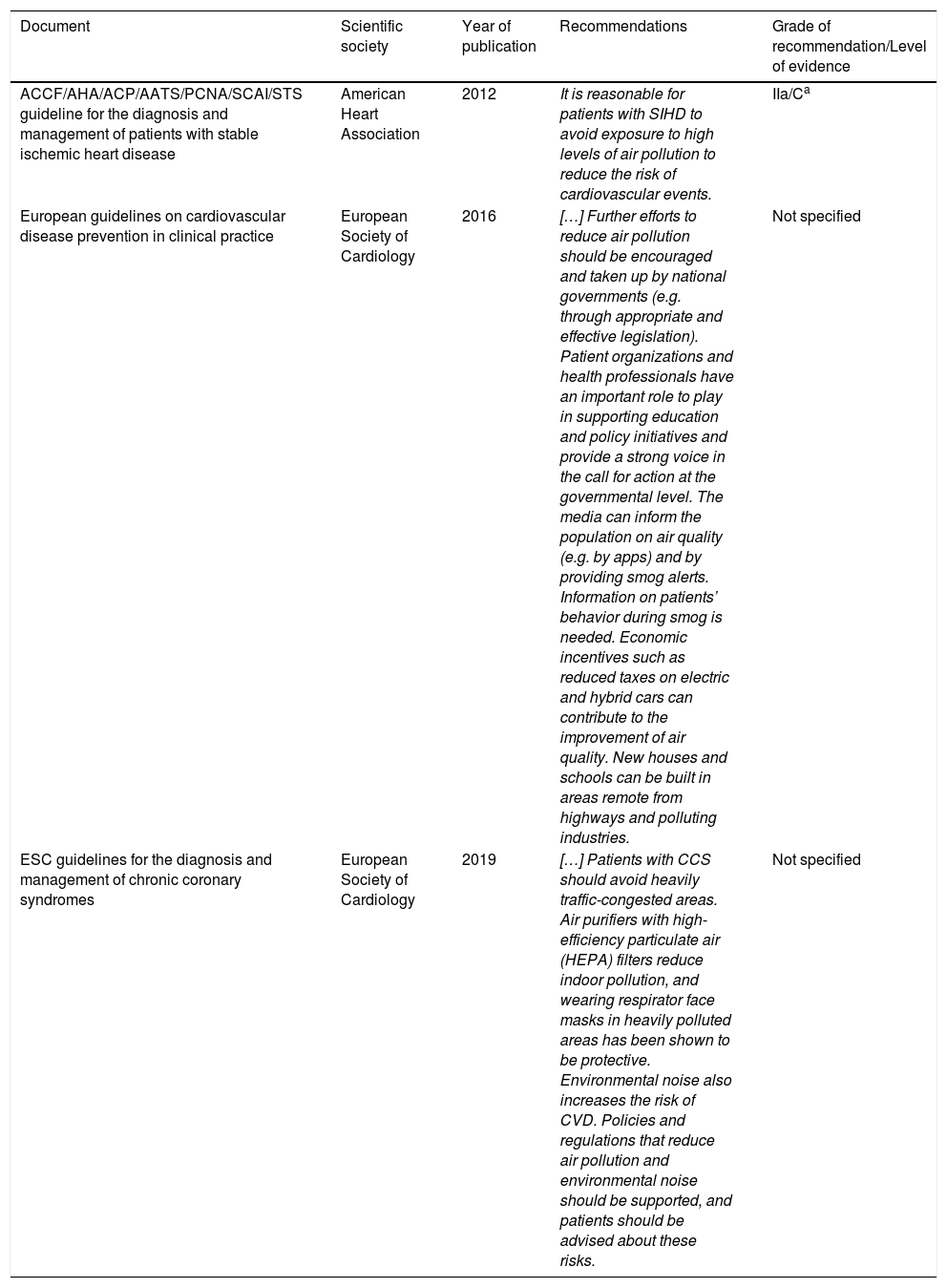

The guidelines on the diagnosis and management of coronary syndrome (AHA, 2012; ESC, 2019) provide specific recommendations (avoiding exposure to air pollution, use of air purifiers with high-efficiency particulate air filters, use of face masks in heavily polluted areas). The guidelines on the management of chronic coronary syndrome (ESC, 2019) and the prevention of cardiovascular disease (ESC, 2016) mention the need for population-level policies to reduce air pollution (lowering taxes on electric and hybrid vehicles, building new houses and schools in low-pollution areas, involving clinicians in the development of population education programmes and healthcare policy) (Table 1).

Clinical practice guidelines listing air pollution as a risk factor, and recommendations issued.

| Document | Scientific society | Year of publication | Recommendations | Grade of recommendation/Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease | American Heart Association | 2012 | It is reasonable for patients with SIHD to avoid exposure to high levels of air pollution to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events. | IIa/Ca |

| European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice | European Society of Cardiology | 2016 | […] Further efforts to reduce air pollution should be encouraged and taken up by national governments (e.g. through appropriate and effective legislation). Patient organizations and health professionals have an important role to play in supporting education and policy initiatives and provide a strong voice in the call for action at the governmental level. The media can inform the population on air quality (e.g. by apps) and by providing smog alerts. Information on patients’ behavior during smog is needed. Economic incentives such as reduced taxes on electric and hybrid cars can contribute to the improvement of air quality. New houses and schools can be built in areas remote from highways and polluting industries. | Not specified |

| ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes | European Society of Cardiology | 2019 | […] Patients with CCS should avoid heavily traffic-congested areas. Air purifiers with high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters reduce indoor pollution, and wearing respirator face masks in heavily polluted areas has been shown to be protective. Environmental noise also increases the risk of CVD. Policies and regulations that reduce air pollution and environmental noise should be supported, and patients should be advised about these risks. | Not specified |

Evidence-based methodology developed by the working group participating in these guidelines: Class IIa: it is reasonable to perform procedure/administer treatment; Level of evidence C: recommendation in favour of treatment or procedure being useful/effective - Only diverging expert opinion, case studies, or standard of care.

However, none of the included guidelines for stroke management listed air pollution as a risk factor or proposed prevention strategies addressing this issue.

DiscussionAccording to our review, air pollution was not listed as a risk factor for stroke in any of the included clinical practice guidelines. A small number of the guidelines (3/24), issued by cardiology societies, did include air pollution as a risk factor. Insufficient information is available on assessing the impact of air pollution on the population; furthermore, the available guidelines do not specify whether specific recommendations have been issued on the topic for patients. Guidelines also do not underscore the importance of involving clinicians in the development of population-level policies aimed at reducing the risk attributable to air pollution.

Since the AHA first recognised air pollution as a cardiovascular risk factor in 2004, many studies have demonstrated the association between exposure to air pollution and the risk and prognosis of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. However, none of the stroke management guidelines reviewed mention air pollution.

Explicit mention of exposure to air pollution should be included in future versions of stroke prevention guidelines, as is the case with the most recent update of the SEN’s guidelines for primary and secondary stroke prevention.12 Clinical practice guidelines should also underscore the need for neurologists to play an active role in preventing this risk factor; the use of maps of high-pollution areas and tools for calculating vascular risk will enable clinicians to make individualised recommendations to reduce the risk of cerebrovascular disease associated with exposure to air pollution.13

Please cite this article as: Avellaneda-Gómez C, Roquer J, Vivanco-Hidalgo R. Reconocimiento de la contaminación atmosférica como factor de riesgo de ictus en las guías de práctica clínica para las enfermedades cerebrovasculares: revisión de la literatura. Neurología. 2021;36:480–483.