Intravenous immunoglobulins are a frequent treatment for a variety of neurological diseases.1 This treatment has been associated with thromboembolic complications, with an incidence ranging between 1.2% and 11.3%.2 The pathogenic mechanisms of the disease include increased plasma viscosity, increased platelet count and adhesion, and presence of procoagulant antibodies and coagulation factors not eliminated by immunoglobulin fractionation.2,3

Superior vena cava thrombosis in patients receiving intravenous immunoglobulins is an infrequent complication that has rarely been described in the literature.4 Management of this complication may be difficult, especially in patients with a central venous catheter, since no specific management guidelines have been established to date.4,5

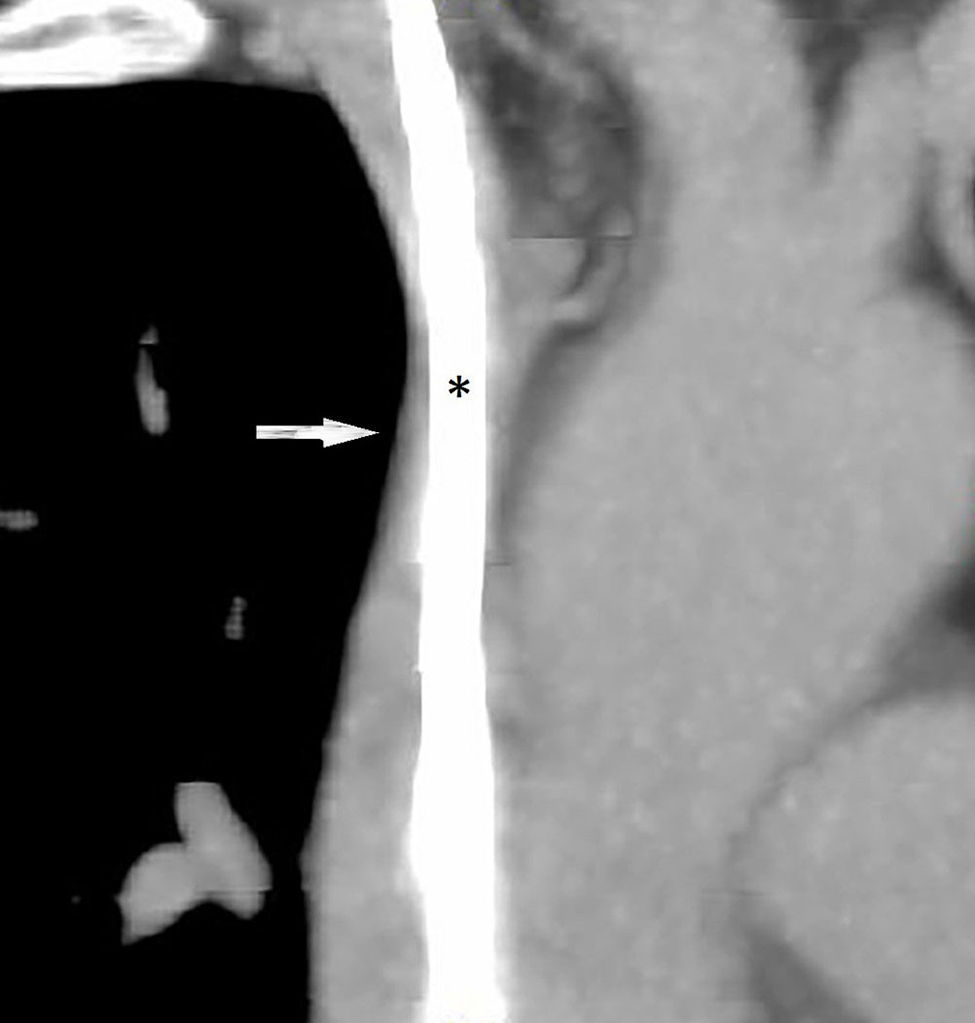

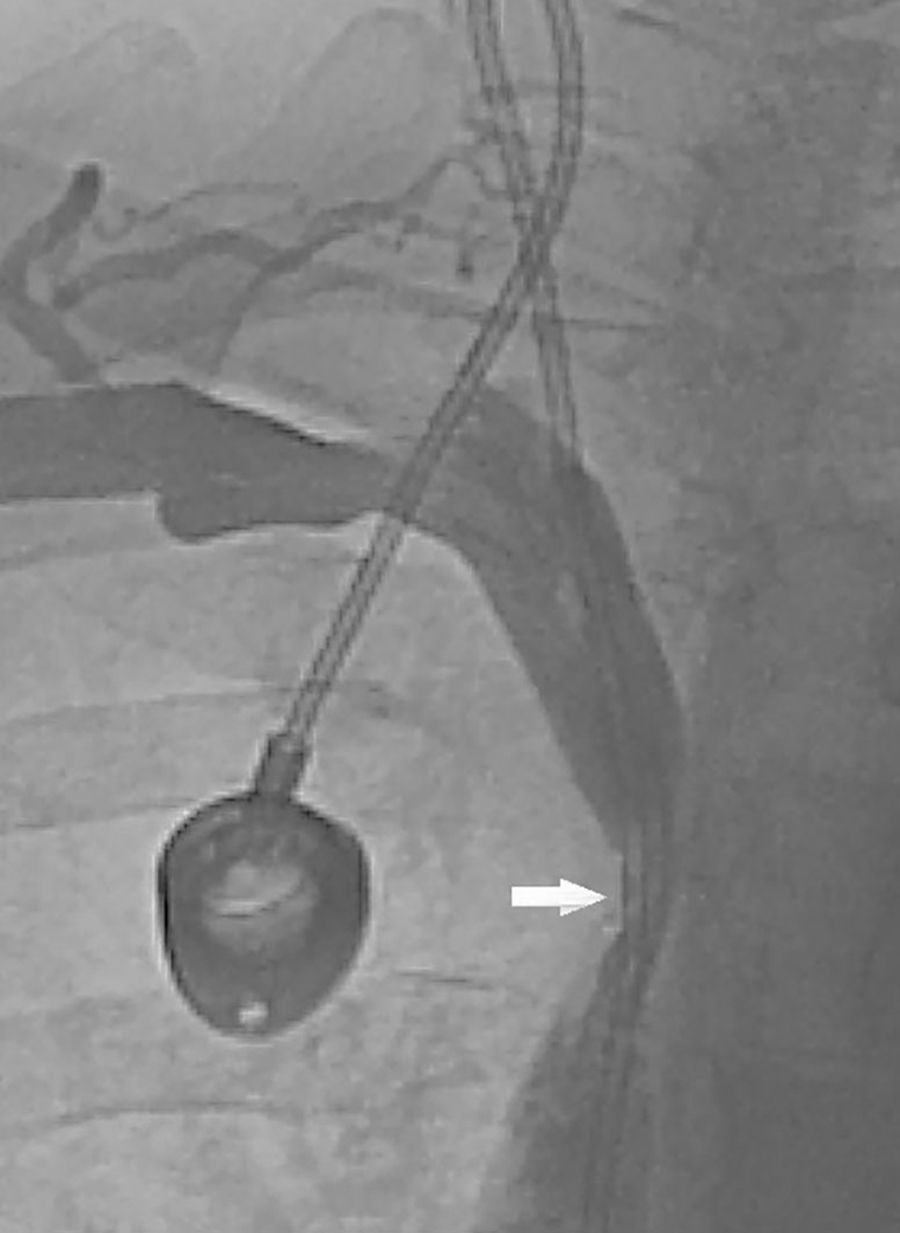

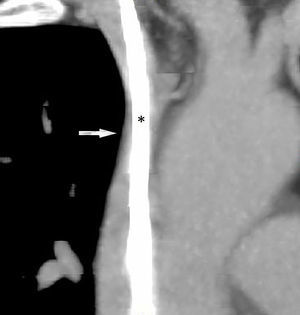

We present the case of a 57-year-old female smoker diagnosed with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. She was in treatment with azathioprine, deflazacort 6mg/24h, and intravenous immunoglobulins dosed at 0.5g/kg/day and administered over 12 hours per day for 4 days every month. She had no other relevant history. Immunglobulin therapy had been started 3 years earlier, by means of a subcutaneous reservoir attached to a catheter in the superior vena cava. The catheter had been implanted following multiple episodes of thrombophlebitis and extravasation. She had a 3-month history of cervico-facial oedema. A metabolic study performed to rule out alterations linked to oedema yielded normal results, including normal thyroid and renal function, normal albumin and total protein levels in serum, normal protein levels in urine, and no changes in urine sediment. A transthoracic echocardiogram displayed no abnormalities. A chest CT scan with contrast revealed that the catheter occupied nearly the entire lumen of the proximal segment of the superior vena cava (Fig. 1). A cavography demonstrated mild stenosis of the superior vena cava, which was complicated by a thrombus around the catheter (Fig. 2). A complete autoimmunity and hypercoagulation study ruled out a prothrombotic state. We decided to start anticoagulation therapy with enoxaparin dosed at 60mg/12h. The catheter was removed a month later. A follow-up cavography revealed no thrombosis in the lumen of the vena cava or around the catheter; mild residual stenosis persisted. Cervico-facial oedema disappeared. We decided to continue treatment with peripheral venous immunoglobulins, maintain anticoagulation therapy with acenocoumarol for an additional 5 months, and subsequently administer antithrombotics with each infusion (enoxaparin 40mg/24h) as prophylaxis.

Superior vena cava syndrome results from obstruction of blood flow through the superior vena cava due to compression or occlusion. In around 60% of the cases, this syndrome is caused by malignancies, the most frequent being lung carcinoma and lymphoma. The most common benign aetiology has to do with placement of such intravascular devices as reservoir catheters or pacemaker electrodes6; the associated incidence of thrombosis varies from study to study (2%-67%).5

Venous thrombosis is caused by 3 main factors known collectively as the Virchow triad: stasis, hypercoagulability, and endothelial injury.7 Central venous catheters may damage the vascular endothelium and promote venous stasis by obstructing blood flow through the vena cava. Patients with these catheters may present hypercoagulable states associated with the underlying disease, with primary clotting disorders, or with the treatment itself. In our patient, immunoglobulin treatment may have favoured this mechanism by completing the triad.2

Risk of thromboembolism in patients receiving immunoglobulins must be calculated based on age, presence of cardiovascular risk factors, immobility, prior thromboembolic complications, and concomitant use of prothrombotic drugs, including corticosteroids, which favour platelet aggregation and inhibit the fibrinolytic system. The literature reports cases of deep vein thrombosis secondary to immunoglobulin use, normally at high doses or after long treatment periods.2,8

Given the lack of randomised clinical trials, management of superior vena cava syndrome secondary to thrombosis of an intravascular catheter has not been protocolised.5 Treatment must therefore be tailored to each patient according to the degree of stenosis and severity of clinical symptoms. Less severe cases, such as that of our patient, may benefit from conservative treatment with anticoagulants until symptoms resolve.5 We opted to remove the reservoir in our patient since it was believed to significantly increase the risk of a new thrombotic event. Given that early catheter removal has failed to deliver a better prognosis in thrombosis,5 we decided to remove the catheter a month after initiating anticoagulation therapy to prevent potential thromboembolic complications secondary to thrombus mobilisation. We maintained anticoagulation therapy for 6 months since the risk factor for deep vein thrombosis (the catheter) was understood to be temporary.9 In more severe cases, endovascular treatment with balloon angioplasty and stenting is the first-line option since its effectiveness is similar to that of surgery and it is associated with fewer complications.10 The duration of anticoagulation therapy for patients in whom the catheter remains in place has not been established.5 We recommend applying preventive measures before immunoglobulin infusion (hydration, antiplatelet drugs or low molecular weight heparins, infusion during no less than 8 hours, and administering the normal dose [2g/kg] in fractions of 0.4g/kg/day for 5 days) given the high risk of thrombosis, even in patients with no history of thromboembolic events.2,3,5

In conclusion, presence of a central venous catheter may promote the thrombogenic mechanisms associated with immunoglobulin treatment and result in superior vena cava syndrome secondary to superior vena cava thrombosis. When this route of treatment must be used, antithrombotic measures should be taken before each infusion.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Crespo-Burillo JA, Alarcia-Alejos R, Capablo-Liesa JL. Síndrome de vena cava superior como complicación del tratamiento con inmunoglobulinas intravenosas. Neurología. 2017;32:202–204.