Botulinum toxin type A is used to treat spasticity and dystonia. However, its relationship with muscle morphology has not been studied. The action mechanism of botulinum toxin is based on the inhibition of acetylcholine release. Therefore, larger doses of toxin would be needed to treat larger muscles. This study aims to establish whether there is a discrepancy between muscle morphology and the botulinum toxin doses administered.

MethodsWe dissected, and subsequently measured and weighed, muscles from the upper and lower limbs and the head of a fresh cadaver. We consulted the summary of product characteristics for botulinum toxin type A to establish the recommended doses for each muscle and calculated the number of units infiltrated per gramme of muscle.

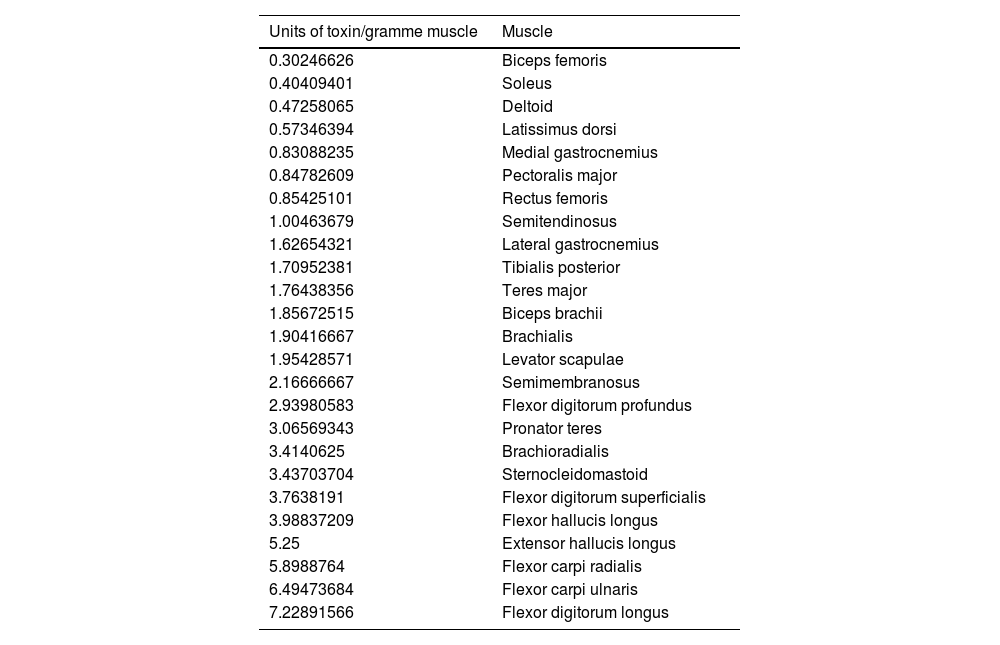

ResultsDifferent muscles present considerable morphological variability, and the doses of botulinum toxin administered to each muscle are very similar. We observed great variability in the amount of botulinum toxin administered per gramme of muscle, ranging from 0.3 U/g in the biceps femoris to 14.6 U/g in the scalene muscles. The mean dose was 2.55 U/g. The doses administered for nearly all lower limb muscles were below this value.

ConclusionsThere are significant differences in morphology between the muscles of the lower limbs, upper limbs, and head, but similar doses of botulinum toxin are administered to each muscle. These differences result in great variability in the number of units of botulinum toxin administered per gramme of muscle.

La toxina botulínica tipo A es un tratamiento para la espasticidad y la distonía. Sin embargo, no se ha estudiado su relación con la morfología muscular. El mecanismo de acción de la Toxina botulínica radica en inhibir la liberación de acetilcolina. Cabe pensar que, a mayor tamaño muscular, mayor dosis de toxina necesaria. El objetivo del presente trabajo es poner de manifiesto la existencia o no de una discrepancia entre las dosis de toxina botulínica utilizadas y la morfología muscular.

MétodoSe procedió a la disección de los músculos de las extremidades inferiores, superiores y de la cabeza, en cadáver fresco para su pesaje y medición. De la ficha técnica de las toxinas botulínica tipo A se obtuvieron las dosis recomendadas para cada músculo. Se calculó la Unidad de toxina botulínica tipo A infiltrada por gramo muscular.

ResultadosExiste una gran variabilidad morfológica entre los músculos; las dosis de toxina botulínica administradas por músculo son muy similares. Existe una gran variabilidad de la Unidad de toxina botulínica por gramo muscular: desde los 0,3 U/gr del bíceps femoral hasta 14,6 U/gr del escaleno. La dosis media de unidad de toxina por gramo muscular fue de 2,55 U/gr. Casi todos los músculos de la extremidad inferior quedan por debajo de esta media.

ConclusionesExisten diferencias morfológicas significativas entre los músculos de la extremidad inferior, superior y la cabeza pero las dosis de toxina botulínica infiltradas por músculo son similares. Estas diferencias hacen que la Unidad de toxina recibida por gramo muscular sea muy variable.

Botulinum toxin has been used in humans for over 40 years, after Drachman1 first demonstrated that it causes skeletal muscle paralysis in animals. This discovery encouraged Allan Scott to investigate its use in humans, specifically in the management of strabismus; this research, conducted between 1960 and 1970, led the United States Food and Drug Administration to approve the drug for the treatment of strabismus in humans in 1979. The following years saw a considerable expansion of research into the use of botulinum toxin in different areas of medicine, to treat such disorders as cervical dystonia, overactive bladder, hyperhidrosis, sialorrhoea, spasticity, and migraine.2 Currently, 3 types of botulinum toxin A and one type of botulinum toxin B are commercially available. The type A drugs are Botox (onabotulinumtoxinA), produced by Allergan Inc., Xeomin (incobotulinumtoxinA), manufactured by Merz Pharma, and Dysport (abobotulinumtoxinA), produced by Ipsen. The type B botulinum toxin is Myobloc (rimabotulinumtoxinB). All 3 type A botulinum toxins present similar action mechanisms. According to the summary of product characteristics for onabotulinumtoxinA, the drug “blocks peripheral acetylcholine release at presynaptic cholinergic nerve terminals by cleaving SNAP-25, a protein integral to the successful docking and release of acetylcholine from vesicles situated within the nerve endings”; in other words, it selectively, transiently, and reversibly blocks neurotransmission in cholinergic nerve terminals of the neuromuscular junction, causing weakness and atrophy of the infiltrated muscle.

Historically, research into the use of botulinum toxin in humans has always followed a similar pattern: a clinical trial is conducted in which a range of doses are administered to a particular muscle and to treat a particular disorder, and subsequent studies seek to optimise that dose in terms of dilution, dosage, anatomical disposition of the muscle, and infiltration techniques.3

However, little or no research has addressed muscle morphology. Therefore, it seems logical to consider that, if the action mechanism of botulinum toxin lies in the inhibition of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction, then larger muscles would require higher doses of the drug for the same effect to be achieved. Accumulated professional experience with botulinum toxin, particularly in the treatment of dystonia, spasticity, and migraine, suggests that there may be a discrepancy between the authorised doses and those actually used for different-sized muscles. In the light of this, the present study aims to establish whether there exists such a discrepancy between the recommended and the actual doses of botulinum toxin A used, in relation to muscle size, in the treatment of adult patients with spasticity and cervical dystonia.

Material and methodsWe dissected the muscles of the lower limbs, upper limbs, and head of the fresh (unprocessed) cadaver of a 73-year-old woman with no history of relevant neurological disease, prolonged periods of bed rest, or pharmacological treatment that may affect skeletal muscle. After dissection, muscles were weighed and measured to record their length and maximum diameter. We took measurements bilaterally and used the mean value.

The recommended doses for each muscle are taken from the summary of product characteristics for botulinum toxin A. As some types of botulinum toxin A are not approved for all muscles, and because the recommendations for cervical dystonia refer to the dose per infiltration session, rather than the dose per muscle, we used the mean real-life doses reported in a recent expert consensus statement4 to calculate the units of toxin per gramme of muscle.

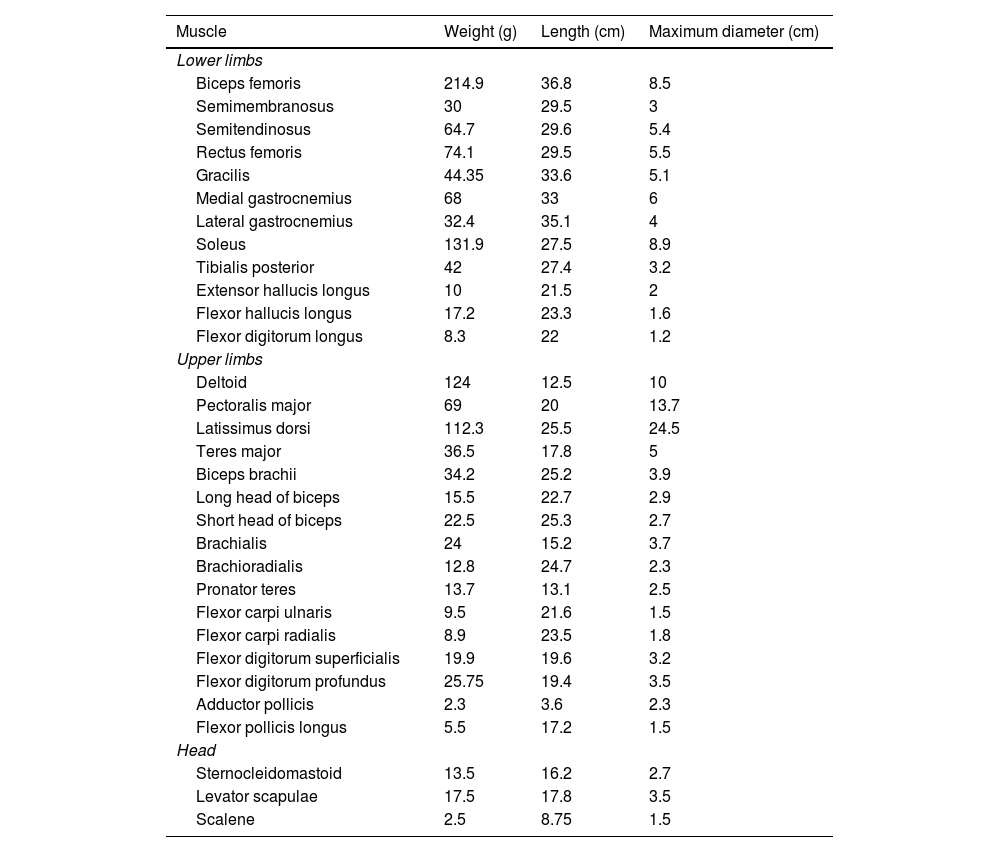

ResultsTable 1 shows the weight, length, and maximum diameter of each muscle studied.

Morphological measurements of muscles.

| Muscle | Weight (g) | Length (cm) | Maximum diameter (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limbs | |||

| Biceps femoris | 214.9 | 36.8 | 8.5 |

| Semimembranosus | 30 | 29.5 | 3 |

| Semitendinosus | 64.7 | 29.6 | 5.4 |

| Rectus femoris | 74.1 | 29.5 | 5.5 |

| Gracilis | 44.35 | 33.6 | 5.1 |

| Medial gastrocnemius | 68 | 33 | 6 |

| Lateral gastrocnemius | 32.4 | 35.1 | 4 |

| Soleus | 131.9 | 27.5 | 8.9 |

| Tibialis posterior | 42 | 27.4 | 3.2 |

| Extensor hallucis longus | 10 | 21.5 | 2 |

| Flexor hallucis longus | 17.2 | 23.3 | 1.6 |

| Flexor digitorum longus | 8.3 | 22 | 1.2 |

| Upper limbs | |||

| Deltoid | 124 | 12.5 | 10 |

| Pectoralis major | 69 | 20 | 13.7 |

| Latissimus dorsi | 112.3 | 25.5 | 24.5 |

| Teres major | 36.5 | 17.8 | 5 |

| Biceps brachii | 34.2 | 25.2 | 3.9 |

| Long head of biceps | 15.5 | 22.7 | 2.9 |

| Short head of biceps | 22.5 | 25.3 | 2.7 |

| Brachialis | 24 | 15.2 | 3.7 |

| Brachioradialis | 12.8 | 24.7 | 2.3 |

| Pronator teres | 13.7 | 13.1 | 2.5 |

| Flexor carpi ulnaris | 9.5 | 21.6 | 1.5 |

| Flexor carpi radialis | 8.9 | 23.5 | 1.8 |

| Flexor digitorum superficialis | 19.9 | 19.6 | 3.2 |

| Flexor digitorum profundus | 25.75 | 19.4 | 3.5 |

| Adductor pollicis | 2.3 | 3.6 | 2.3 |

| Flexor pollicis longus | 5.5 | 17.2 | 1.5 |

| Head | |||

| Sternocleidomastoid | 13.5 | 16.2 | 2.7 |

| Levator scapulae | 17.5 | 17.8 | 3.5 |

| Scalene | 2.5 | 8.75 | 1.5 |

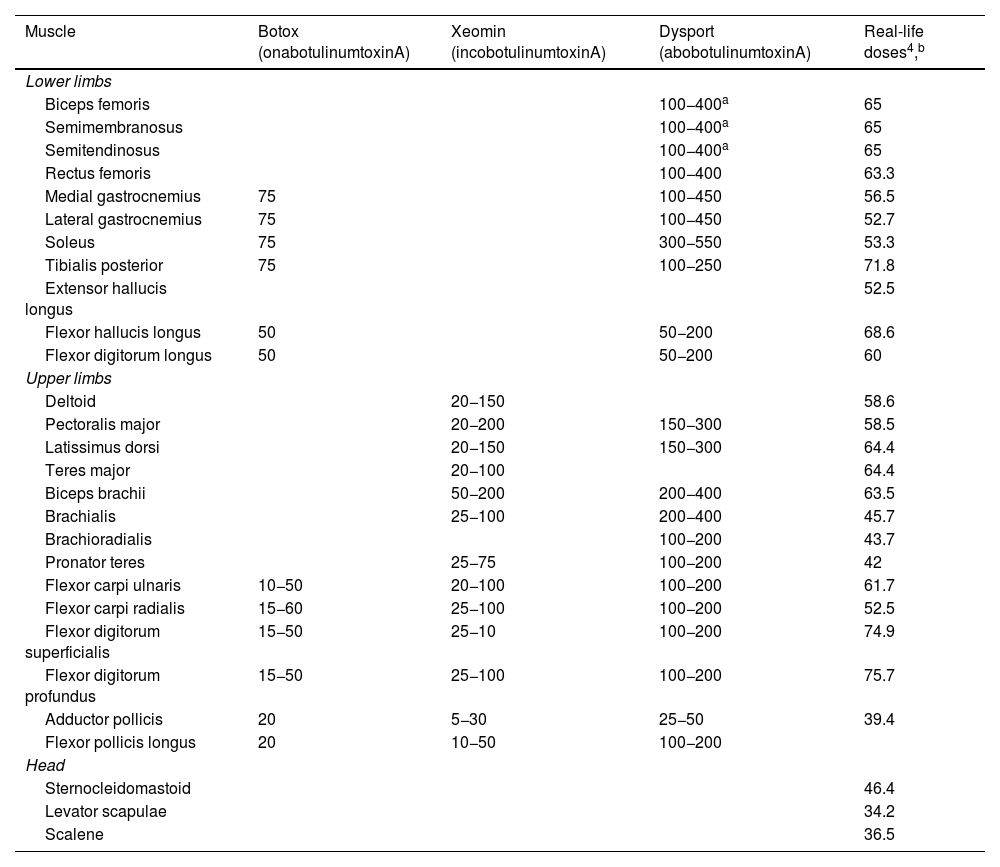

Table 2 shows the recommended botulinum toxin A doses for each muscle, and Table 3 shows the mean doses reported in a recent international consensus statement on the treatment of spasticity and dystonia (that article does not issue recommendations on abobotulinumtoxinA).

Recommended and real-life doses of botulinum toxin for each muscle.4

| Muscle | Botox (onabotulinumtoxinA) | Xeomin (incobotulinumtoxinA) | Dysport (abobotulinumtoxinA) | Real-life doses4,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limbs | ||||

| Biceps femoris | 100−400a | 65 | ||

| Semimembranosus | 100−400a | 65 | ||

| Semitendinosus | 100−400a | 65 | ||

| Rectus femoris | 100−400 | 63.3 | ||

| Medial gastrocnemius | 75 | 100−450 | 56.5 | |

| Lateral gastrocnemius | 75 | 100−450 | 52.7 | |

| Soleus | 75 | 300−550 | 53.3 | |

| Tibialis posterior | 75 | 100−250 | 71.8 | |

| Extensor hallucis longus | 52.5 | |||

| Flexor hallucis longus | 50 | 50−200 | 68.6 | |

| Flexor digitorum longus | 50 | 50−200 | 60 | |

| Upper limbs | ||||

| Deltoid | 20−150 | 58.6 | ||

| Pectoralis major | 20−200 | 150−300 | 58.5 | |

| Latissimus dorsi | 20−150 | 150−300 | 64.4 | |

| Teres major | 20−100 | 64.4 | ||

| Biceps brachii | 50−200 | 200−400 | 63.5 | |

| Brachialis | 25−100 | 200−400 | 45.7 | |

| Brachioradialis | 100−200 | 43.7 | ||

| Pronator teres | 25−75 | 100−200 | 42 | |

| Flexor carpi ulnaris | 10−50 | 20−100 | 100−200 | 61.7 |

| Flexor carpi radialis | 15−60 | 25−100 | 100−200 | 52.5 |

| Flexor digitorum superficialis | 15−50 | 25−10 | 100−200 | 74.9 |

| Flexor digitorum profundus | 15−50 | 25−100 | 100−200 | 75.7 |

| Adductor pollicis | 20 | 5−30 | 25−50 | 39.4 |

| Flexor pollicis longus | 20 | 10−50 | 100−200 | |

| Head | ||||

| Sternocleidomastoid | 46.4 | |||

| Levator scapulae | 34.2 | |||

| Scalene | 36.5 | |||

Units of toxin administered per gramme of muscle, in ascending order. The scalene and adductor pollicis are excluded.

| Units of toxin/gramme muscle | Muscle |

|---|---|

| 0.30246626 | Biceps femoris |

| 0.40409401 | Soleus |

| 0.47258065 | Deltoid |

| 0.57346394 | Latissimus dorsi |

| 0.83088235 | Medial gastrocnemius |

| 0.84782609 | Pectoralis major |

| 0.85425101 | Rectus femoris |

| 1.00463679 | Semitendinosus |

| 1.62654321 | Lateral gastrocnemius |

| 1.70952381 | Tibialis posterior |

| 1.76438356 | Teres major |

| 1.85672515 | Biceps brachii |

| 1.90416667 | Brachialis |

| 1.95428571 | Levator scapulae |

| 2.16666667 | Semimembranosus |

| 2.93980583 | Flexor digitorum profundus |

| 3.06569343 | Pronator teres |

| 3.4140625 | Brachioradialis |

| 3.43703704 | Sternocleidomastoid |

| 3.7638191 | Flexor digitorum superficialis |

| 3.98837209 | Flexor hallucis longus |

| 5.25 | Extensor hallucis longus |

| 5.8988764 | Flexor carpi radialis |

| 6.49473684 | Flexor carpi ulnaris |

| 7.22891566 | Flexor digitorum longus |

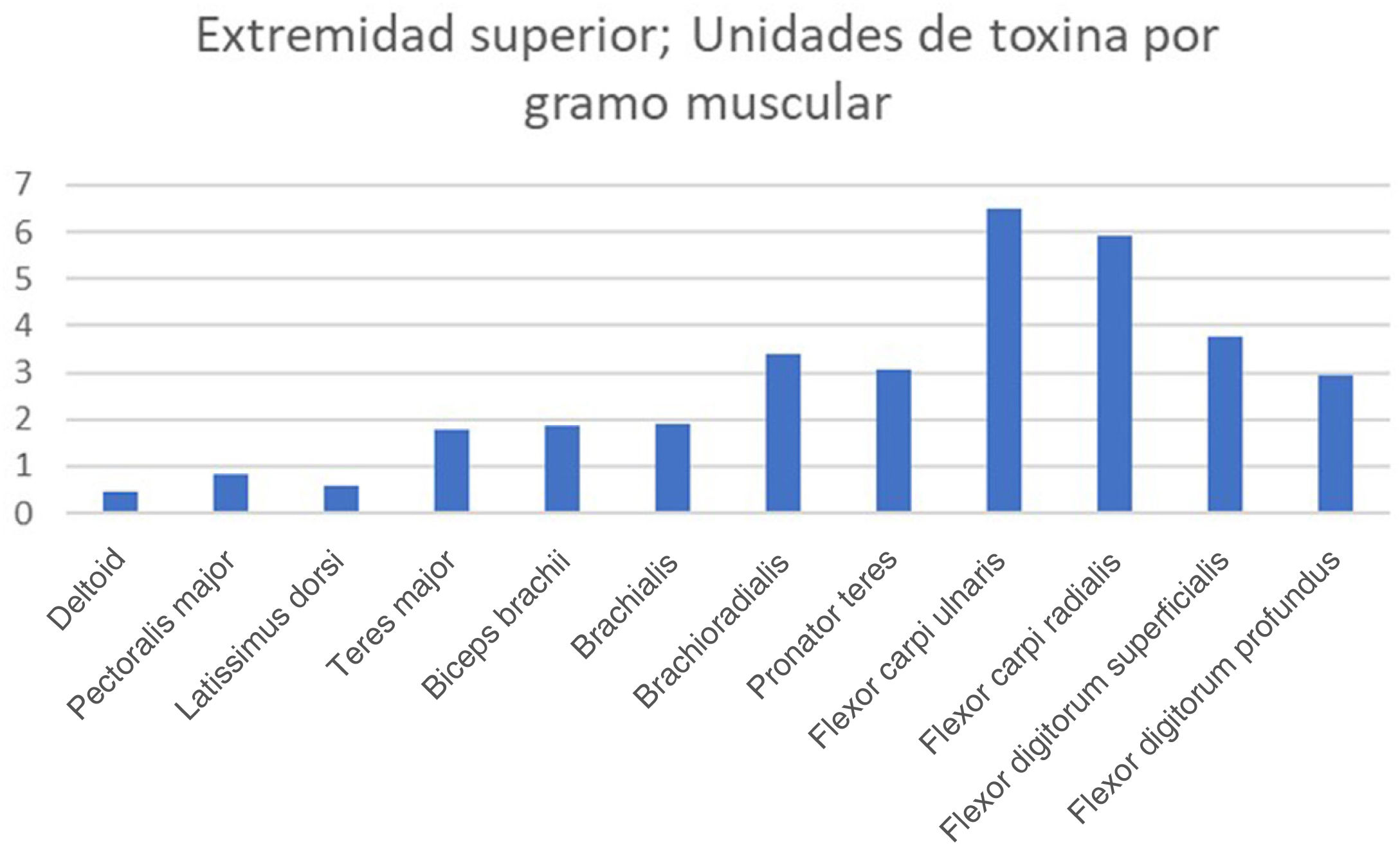

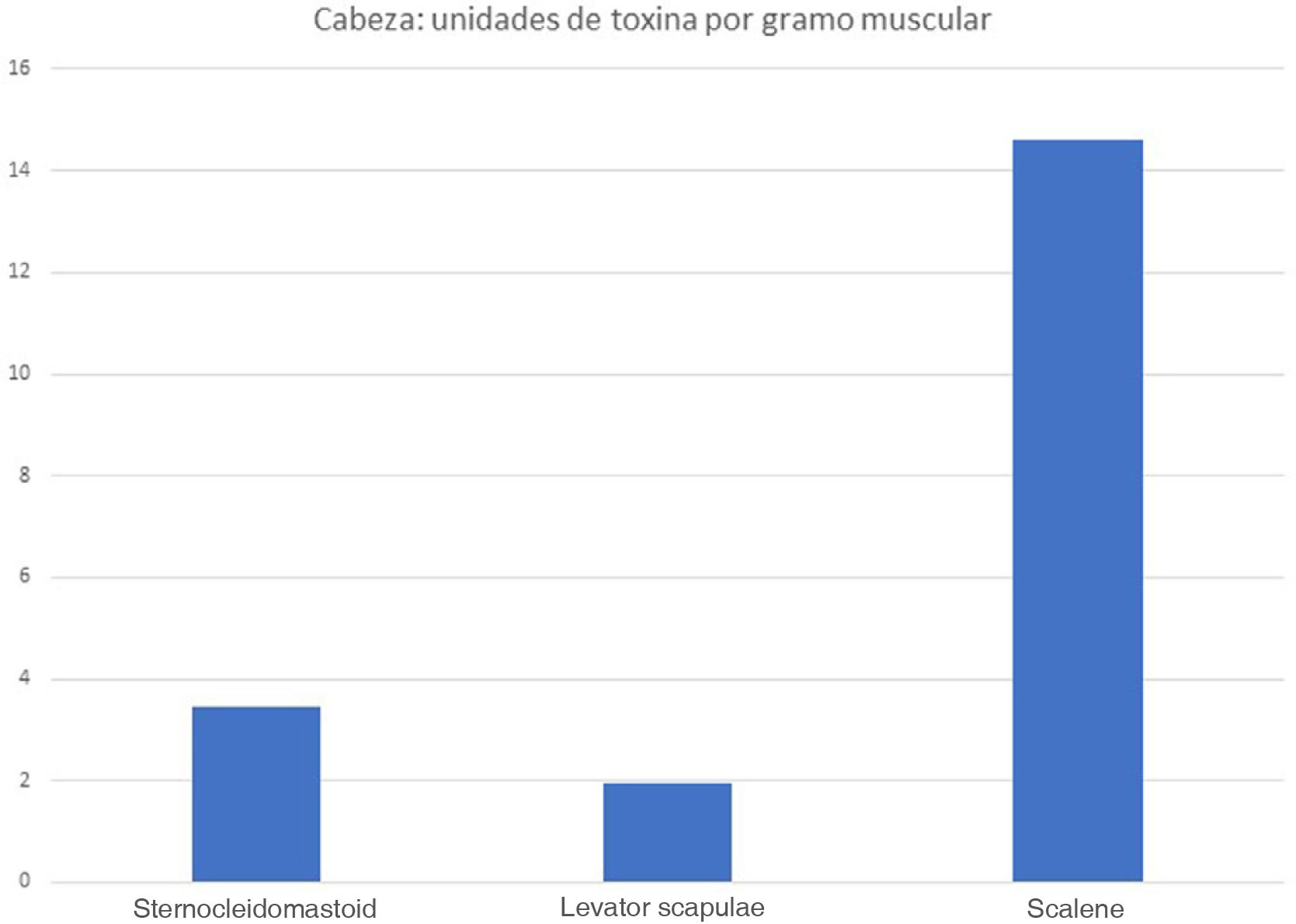

The real-life doses (units of toxin per gramme of muscle) for onabotulinumtoxinA and incobotulinumtoxinA ranged from 0.3 U/g for the biceps femoris to 14.6 U/g for the scalene muscles. Figs. 1–3 present the units of toxin administered per gramme of muscle for the lower limbs, upper limbs, and head, respectively.

If we exclude outliers, such as the scalene muscles and adductor pollicis, the mean dose was 2.55 U/g. With the exception of the flexor hallucis longus and the extensor hallucis longus, which weigh the least of all muscles in the leg, all muscles in the lower limb are below this cut-off point; several muscles of the upper limb (the heaviest muscles, such as the deltoid, latissimus dorsi, teres major, biceps brachii, and brachialis) are also below this cut-off point.

DiscussionSeveral studies have demonstrated the efficacy of botulinum toxin A in the treatment of spasticity5 and cervical dystonia.6 However, the scientific community continues to search for ways to improve the efficacy of these drugs, either through correct selection of target muscles according to the different patterns of involvement,7 through the use of technical guidelines for infiltration,8 or by administering higher doses than have been officially approved.9 These studies demonstrate the need to expand our knowledge in order to improve the efficacy of botulinum toxin infiltration in patients with spasticity and dystonia.

Articles in the literature suggest that correct infiltration is already possible with localisation techniques (electromyography, electrical stimulation, or ultrasound),10 and that strategies for dilution of the drug and selecting the target muscle are very clear. Therefore, new approaches are needed to make further progress. In this sense, muscle size may be an important consideration when establishing toxin dose. For instance, plantar flexor muscle spasticity is treated with infiltration of the medial (68 g) and lateral (32.4 g) heads of the gastrocnemius, the soleus (131.9 g), and the tibialis posterior (42 g) in patients presenting inversion. If we exclusively consider the weight of each muscle, then the soleus should receive approximately half of the total dose; however, in clinical practice, the same dose is administered to the lateral and medial heads of the gastrocnemius as to the soleus, with the tibialis posterior receiving a little more. All 4 of these muscles receive less than the mean dose per gramme of muscle, which may explain reports of incomplete response to infiltration. There are 2 possible reasons for this situation. Firstly, muscle weight is not the sole factor analysed; rather, the anatomical pattern is also taken into account (mono- or biarticular muscle; muscle action). The other reason is the limitation on the total dose to be used in each infiltration: 400 units for onabotulinumtoxinA and incobotulinumtoxinA and 1500 for abobotulinumtoxinA.

There is a clear morphological difference between the muscles of the lower limbs and those of the upper limbs, with lower limb muscles being much larger in terms of weight, length, and maximum diameter. This morphological difference is reflected in the greater force exerted by the muscles of the lower limbs.11 However, there is little difference in the approved doses for these muscle groups: the recommended dose of abobotulinumtoxinA for the biceps femoris (214 g) is 100−400 U, with a real-life mean dose of 65 U, whereas the recommended dose for the biceps brachii (34.2 g) is 200−400 U, with a mean real-life mean dose of 63.5 U. It seems logical that if we seek to weaken a larger, stronger muscle, we would need to use higher doses of botulinum toxin.

The dose-dependent effect of botulinum toxin is well known. Pittock et al.12 analysed the effect of 3 doses (500, 1000, and 1500 U) of abobotulinumtoxinA on spastic equinovarus deformity after stroke; the best results were achieved with 1500 U, and significant effects were also observed with 1000 U of toxin, but not with 500 U.

To address this issue, some studies have analysed the use of higher doses and more flexible time periods between infiltrations. For instance, the TOWER study13 concluded that the administration of 800 units of incobotulinumtoxinA is safe, enables treatment of more muscle groups, and improves the efficacy of infiltration, as is the case with higher doses of other toxins.14 Wissel15 proposes an interval of 6 weeks between infiltrations in the treatment of cervical dystonia. Both strategies, increasing doses and decreasing intervals between infiltrations, have been shown to be efficacious and not to cause relevant secondary reactions in selected patients.

However, we must be cautious when using higher doses due to the risk of undesired effects, such as increased weakness or systemic diffusion of the toxin; however, studies addressing the safety of using increased doses of the drug conclude that this risk is small.16

Until high-dose botulinum toxin therapy is authorised, we must seek to distribute the drug in the most reasonable way, taking into account each muscle’s anatomical function, the pattern of spasticity/dystonia, and the best way of optimising the toxin; the morphological structure (length and weight) of the target muscles should also be considered.

The greatest limitation of our study is that muscle measurements were taken from a single patient, who presented neither spasticity nor dystonia. Future studies are needed to establish whether muscle morphology should be taken into account in the infiltration of botulinum toxin to treat spasticity and dystonia; muscle ultrasound is probably the best way to take these measurements.17

The muscle study was conducted in a patient without neurological disease. Spasticity is known to cause changes in muscle tissue, for several reasons, including neurological damage, which reduces voluntary motor control, and relative immobilisation due to hemiparesis and disuse of the muscle18; this process is known as the vicious cycle of paresis-disuse-paresis. However, we may expect this phenomenon to affect all muscles equally.

In conclusion, despite significant morphological differences (weight, length, and maximum diameter) between muscle groups, similar doses of botulinum toxin A are administered to the muscles of the lower limbs, upper limbs, and head, resulting in considerable variations in the dose received per gramme of muscle. This is the case for all 3 types of botulinum toxin A.

FundingNo specific funding was received for this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.